Calling all Pelvic Floor Athletes: Singing is a Sport

Note: If you missed my last post, read about the three diaphragm (voice-to-pelvic floor) approach here: https://hermanwallace.com/blog/the-voice-of-pelvic-healthbuilding-a-3d-treatment-toolbox

How well can you speak when you are nervous? How well can a person sing if they are crying? What happens to the pelvic floor if someone is nervous or crying, or both? It doesn’t take too much investigation to realize that the health of our voice and pelvic floor are intimately intertwined – and tied to – our stress response.

We know the way we respond to stress impacts our performance. So, when we ask what makes someone a pelvic floor athlete – the answer is – anything that person does that impacts their stress response. If the voice is intimately tied to the stress response as well, then the sport of voicing, or singing, qualifies as an athletic event for the pelvic floor. Thankfully, we have a long string of evidence-base to support the impact of breathing on the pelvic floor, but what about voicing?

The concept of using a three-diaphragm model in rehabilitation was introduced in Medical Therapeutic Yoga (2016) based on the original five-diaphragm theory suggested by Bordoni and Zanier in 2015.1 Since that time, the science of how the voice and the use of music impact rehabilitation outcomes, has continued to evolve.

How music and sound enable learning and impact the mind-body complex is a long-pursued scientific question for every season of the human lifespan, from early childhood development to the golden years of senior living. With regards to motor rehabilitation, the last 25 years of research has supported the notion that musical rhythm entrains movement in patients with neurological disorders.2 In people with acute and persistent pain, results from a meta-analysis of 97 trials suggest that “music interventions overall have beneficial effects on pain intensity, emotional distress from pain, use of anesthetic, opioid and non-opioid agents, heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and respiration rate.”3

Across healthy populations, music has been shown to impact several biomarkers. In a systematic review of 44 studies, half measured the stress hormone cortisol and of those, 100% demonstrated a stress modulation effect of listening to music, chiefly through reduction of cortisol.4 Blood glucose levels also improved in response to music listening in the same analysis.

The human voice, however, is the original instrument, which means listening to the quality of it offers two tools: therapeutic and diagnostic. In other words, the phrase “Are you listening to your patients (and yourself)?” becomes more than just a superficial question about hearing someone. Listening to the voice becomes another way of evaluating the pelvic floor.

Are You Really Listening to Your Patient’s (and Your) Voice?

Listening to someone’s voice can offer you instant and intimate insight into the overall health of the person. The anatomical and neurophysiological connections of the voice-to-pelvic floor are well defined, while investigation into the detailed functioning between the voice and pelvic floor is emerging. In a small study of 11 participants, counting (inclusion of glottal function) improved balance in postpartum women versus not including the laryngeal diaphragm.5 In another small study of opera singers, transperineal ultrasound imaging was used to confirm that the professional vocalists did indeed recruit the pelvic floor during singing.6 And in a third small study, 10 untrained subjects (half men, half women) were asked to do various pelvic floor and vocal tasks with pelvic floor responsiveness noted via transabdominal ultrasound imaging, which showed variable results for lengthening and contraction of the pelvic floor during voicing.7 These early studies are a vital guide for future research and understanding of two variables: the role of pelvic floor therapy in vocal performance and the role of the voice in pelvic floor therapy.

What Can Be Learned from Listening to the Quality of the Voice?

First, let’s start with the top diaphragm – the laryngeal diaphragm. The proverbial apple does not fall from the tree, in that vocal habits are often a mirror of the health of nearby structures, such as the jaw and neck.

Clinicians should screen their patients, asking questions like - Does the person clinch the jaw or grind their teeth at night? Do they have existing jaw pain, clicking, headaches, and/or neck pain? Do they get frequent laryngitis or have a chronic throat clear or hoarseness? Do they have acid reflux or postnasal drip? Any of these variables can lead to a degradation of the voice and can easily cause vocal fatigue and/or injury.

Next, if the clinician determines these things exist – a sequela of issues can follow, typically starting with evaluating breath support. If any of the above issues are present, a person typically must drive their voice harder to create sound, which means the demands on the respiratory system increase. Secondary muscles of respiration, typically reserved only for forced expiration, now come into play. Muscles like the abdominal wall, specifically the internal obliques, but also the cervical paraspinals, sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, intercostals, and even the psoas and iliacus, can be recruited during speaking. To help in patient and public health education, I coined and use the phrases “Psoas Speaking, Oblique Speak, and/or Paraspinal Speaking” to make it easier for people without healthcare backgrounds to understand what is happening when they drive their voice too hard to create sound. Clinicians may also be surprised to know just how hard the body will work to create sound, even when it creates a downward pressure gradient in the pelvic floor, as happens in many cases where vocal dysfunction is present.

But let’s return to why the person is using forced expiration, which is the strategy most often employed when it becomes increasingly difficult to create sound.

What Do We Know about Forced Expiration?

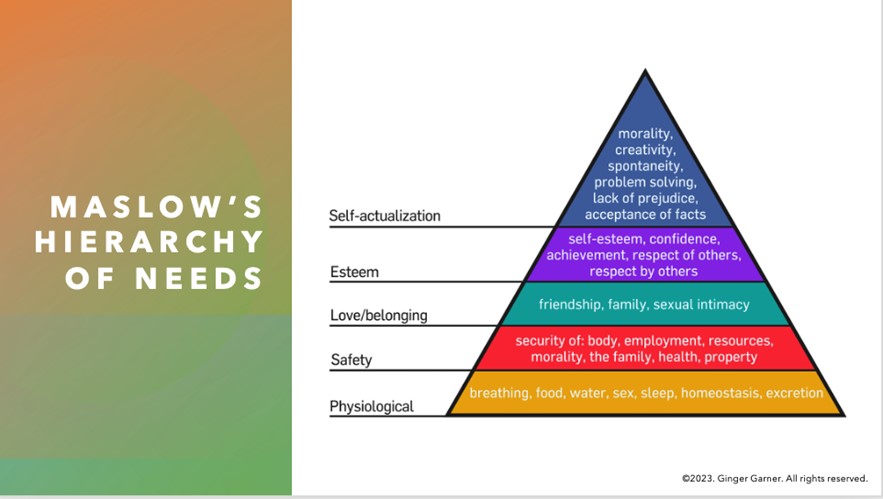

We know that it’s employed typically during a sympathetic nervous system response. That is – forced expiration is a result of the stress response – where if we don’t choose “rest and digest” we are left with fight, flight, freeze, or fawn. Getting our needs met (as outlined in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs - see figure below) as human beings simply cannot happen if we are stuck in a sympathetic nervous system response. Whether or not the person is conscious of it, as Bessel Van der Kolk’s book of the same name tells us, the body keeps the score. Our body will perceive a stress or pain response if we are forcing the laryngeal diaphragm to create sound under chronically bad conditions. But the tricky part, beyond recognizing what vocalizing under bad conditions looks and sounds like is this – the stress response will happen even when the person doesn’t perceive stress or pain. So, it becomes the clinician’s job to help the individual recognize signs of vocal distress and to determine if they can help as a pelvic health practitioner, or whether or not a referral to an ENT, SLP, or another provider may be necessary.

To determine if we can help – we first must recognize the voice as an integral part of pelvic health assessment and intervention.

In a trauma-informed model, the three-diaphragm approach asks the therapist to attune to a person’s basic needs first. We cannot expect to solve their pelvic floor or pelvic girdle problems if we haven’t taken note of the stressors in their life – this means being aware of and screening for social determinants of health, such as whether or not they have a safe space at home, access to sunlight and green space, transportation to and from therapy, and/or whether or not they live in a food desert.

I often use the example of not attuning to the social determinants of health in our patients being akin to not addressing sensorimotor issues in someone with autism spectrum disorder. It’s hard to sit still and learn the math that your teacher wants you to learn if the tag in your sweater feels like a hot match on fire. Right? In the same way, it’s difficult for our patients to resolve their voice, breathing, and/or pelvic floor issues if we are not making sure they feel safe and sound in the therapy environment first. Once we have done that, we can then move to identifying whether or not they would benefit from voice-to-pelvic floor therapy.

The short answer is everyone can benefit from an enhanced model of pelvic floor evaluation that includes voice assessment, or the three-diaphragm model. However, if your patient has an anatomically narrow airway or any of the following issues, a referral could be necessary:

- Asthma

- COPD

- Allergies or Pollutants - environmental, food

- Sleep Apnea or poor sleep quality

- Breathing Anomalies - long COVID, or poor breathing in general that cannot be addressed in pelvic PT/OT

- Reactive airway to exercise - exercise-induced asthma

Our Voice is Our Life

Finally, our goal of Three Diaphragm Therapy is to have a person entrain their voice to their core and pelvic floor movements. Many clinics, mine included, use ultrasound imaging as a clinical go-to tool. However, I want to be clear that you do not need to have imaging to appreciate and evaluate or treat, the voice-to-pelvic floor connection. Red flags for vocal dysfunction to easily screen for in your practice include:

|

|

The voice should be considered as one of the vital biomarkers of pelvic health. Dis”ease” in any of the three diaphragms especially impedes health and well-being, especially since creation of sound and voicing requires two motor systems, the emotional and musculoskeletal or voluntary motor systems.8

As clinicians, we have typically spent all our time focusing on the latter motor system, instead of the former, and now it’s time to do a deep dive to understand just how to influence the emotional motor system in its influence on the three diaphragms and the stress response. Talking is one of the activities of daily living that we all use and need, and most therapists depend on their voice to make a living.

There are many methods to optimizing voice-to-pelvic-floor health in the individual, which is part of the “art” in pelvic health prescription. Learn how to assess and plan interventions using a voice-to-pelvic floor trauma-informed approach at Dr. Garner’s course – The Voice and the Pelvic Floor scheduled for April 6 and September 7, 2024.

Resources:

- Bordoni, B., Zanier, E., 2015. The continuity of the body: hypothesis of treatment of the five diaphragms. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 21, 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2013.0211

- Braun Janzen, T., Koshimori, Y., Richard, N.M., Thaut, M.H., 2022. Rhythm and Music-Based Interventions in Motor Rehabilitation: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15, 789467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.789467

- Lee, J.H., 2016. The Effects of Music on Pain: A Meta-Analysis. J Music Ther 53, 430–477. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thw012

- Finn, S., Fancourt, D., 2018. The biological impact of listening to music in clinical and nonclinical settings: A systematic review. Prog Brain Res 237, 173–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.03.007

- Rudavsky, A., Hickox, L., Frame, M., Philtron, D., Massery, M., n.d. Certain Voicing Tasks Improve Balance in Postpartum Women Compared with Nulliparous Women. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy 10.1097/JWH.0000000000000242. https://doi.org/10.1097/JWH.0000000000000242

- Volløyhaug, I., Semmingsen, T., Laukkanen, A.-M., Karoliussen, C., Bjørkøy, K., 2024. Pelvic floor status in opera singers. a pilot study using transperineal ultrasound. BMC Women’s Health 24, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-02895-6

- Rudavsky, A., Turner, T., 2020. Novel insight into the coordination between pelvic floor muscles and the glottis through ultrasound imaging: a pilot study. Int Urogynecol J 31, 2645–2652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04461-8

- Holstege, G., Subramanian, H.H., 2016. Two different motor systems are needed to generate human speech. J. Comp. Neurol. 524, 1558–1577. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.23898

AUTHOR BIO:

Dr. Ginger Garner PT, DPT, ATC-Ret

Dr. Ginger Garner PT, DPT, ATC-Ret is a clinician, author, educator, and longtime advocate for improving access to physical therapy services, especially pelvic health. She is the founder and CEO of Living Well Institute, where she has been certifying therapists and doctors in Medical Therapeutic Yoga & Integrative Lifestyle Medicine since 2000. She also owns and practices at Garner Pelvic Health, in Greensboro NC, where she offers telehealth and in-person wellness and therapy services. Ginger is the author of multiple textbooks and book chapters, published in multiple languages. She has also presented at over 20 conferences worldwide over 6 continents across a range of topics impacting the pelvic girdle, health promotion, and integrative practices.

Ginger is an active member of APTA, serving as the Legislative Chair for APTA North Carolina, as a Congressional Key Contact for APTA Private Practice, and in the Academy of Pelvic Health. Ginger lives in Greensboro, NC with her partner, 3 sons, and their rescue pup, Scout Finch. Visit Ginger at the websites above and on Instagram and YouTube.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./