Can Dry Needling Help with The Management of Constipation?

Constipation, which includes rectal evacuation disorders, slow transit constipation, and IBS to name a few is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders worldwide (1,2). The complexity of constipation and its impact on a person’s health and quality of life is often misunderstood and common treatment strategies such as diet, exercise, hydration, and stress management can be an oversimplification of what is necessary to effectively manage the disorder (1). From a rehabilitation lens, it is pivotal to prioritize the function of the nervous system when developing a treatment strategy for constipation, considering the nervous system is the central control mechanism of all functions and processes in the human body.

Dry needling, specifically, dry needling with electrical stimulation, is one of the most impactful tools we have in rehabilitation to improve the health and function of the nervous system. Dry needling has evolved from a procedure that utilizes a monofilament needle to deliver mechanical input into “trigger points” in muscle tissue to include the use of a monofilament needle for the delivery of electrical stimulation, which is often described as percutaneous electrical stimulation or neuromodulation. The use of electrical stimulation with dry needling can have a profound effect on improving the healing capacity of tissues and the overall functional recovery of the human body primarily due to the impact it has on the nervous system. Therefore, we must have a sound understanding of the neuroanatomy and physiology of any region of the body and the associated dysfunction to effectively develop and implement a treatment plan.

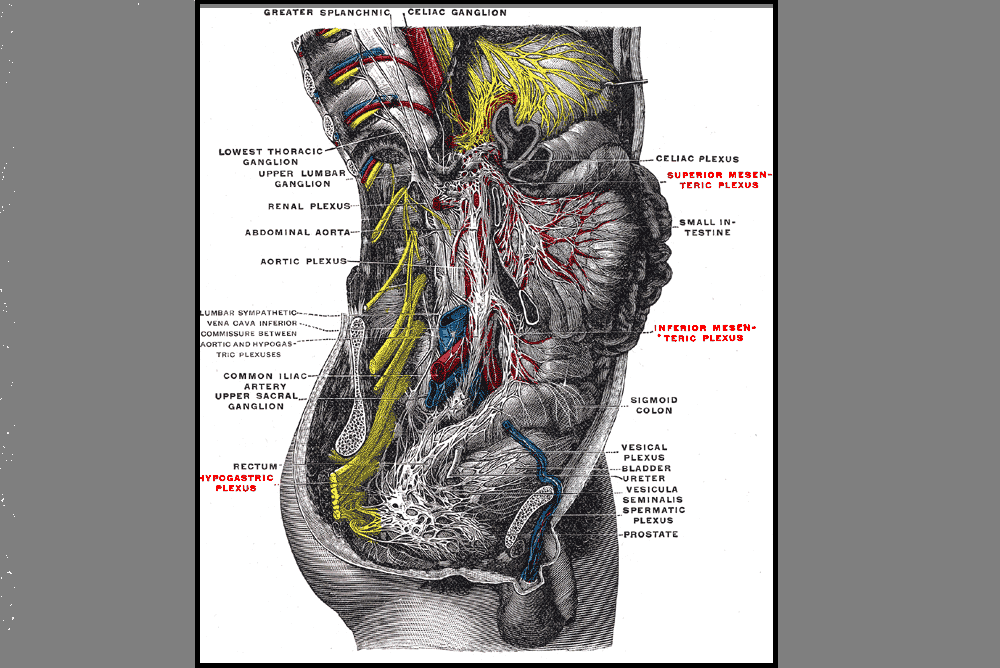

The gastrointestinal system is considered the most complicated system in our body in terms of the number of structures involved in function and regulation and the enormity of neurons that innervate the gastrointestinal tract, and it is yet to be fully understood (3). The enteric nervous system, which is commonly considered the third branch of the autonomic nervous system, is at the center of regulatory control of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and precisely coordinates the function of GI neurons, glial cells, macrophages, interstitial cells, and enteroendocrine cells which drives gut motility and secretions (3). It is interesting to note that the sophistication of the enteric nervous system allows the GI tract to be able to function independently of any neural inputs from the central nervous system (3,4). However, normal physiologic functioning of the GI tract is influenced by bidirectional neuronal connections between the enteric and central nervous systems which is known as the “brain-gut-axis” (3).

Embedded in the walls of the GI tract are the myenteric and submucosal plexuses of the enteric nervous system, which innervate the GI tract and uniquely provide both excitatory and inhibitory motor neurons (4). The myenteric plexus lies between the longitudinal and circular muscle layers of the GI tract and coordinates smooth muscle movements or gut propulsions (“motility”) while the submucosal plexus is found within the connective tissues of the submucosa and regulates secretion, absorption, and blood flow in the GI tract (3,4).

The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems influence the function of the GI tract primarily through integrated neuronal activity with the enteric nervous system versus direct innervation to the wall of the gut, with the exception of blood vessels and sphincters which receive direct sympathetic innervation (3).

Sympathetic inputs to the GI tract regulate secretion and motility and parasympathetic inputs to the distal colon are important for colonic motility and defecation (3).

The function of the somatic nervous system innervating key structures involved with defecation should be equally prioritized to comprehensively evaluate factors contributing to constipation. This may include spinal nerves from the thoracolumbar and sacral vertebral segments, the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, the pudendal nerve, the levator ani nerve, and even the phrenic nerve if we are considering the innervation and function of the diaphragm and the importance of breathing mechanics and control of intraabdominal pressure during voiding.

From a treatment perspective, the most impactful window of access to modulate activity in the gastrointestinal tract using dry needling with electrical stimulation is targeting spinal nerves and associated peripheral nerves and their target organs (primarily muscle tissue) that converge with our autonomic nervous system innervating the gut (5). Additionally, electrical stimulation applied directly over the involved target tissue in the GI tract can help facilitate changes in GI function because the enteric nervous system is embedded in the wall of the GI lumen. The rationale for the use of neuromodulation to impact the function of the gastrointestinal tract is that our system is a bioelectric system, therefore, the application of electrical stimulation can have a profound impact on neuromuscular function which is interrelated with neurovascular, neuroimmune function, neuroinflammatory function, neuroendocrine function and so on (5, 6, 7). There is even evidence that electrical stimulation can impact the concentration of bacterial populations in the GI tract which can influence the overall function of the gut. Lastly, ongoing dysfunction in gastrointestinal tissue or any visceral tissue can create neuromotor dysfunction in associated somatic tissues that may include pain, tissue sensitization, abnormal muscle tone, and abnormal motor control strategies which can be effectively and efficiently treated with dry needling and electrical stimulation.

In conclusion, dry needling with electrical stimulation is one the best tools used in conjunction with traditional rehabilitation strategies to create meaningful, sustainable improvements in the function of the human body. If you want to learn more about the implementation of dry needling into your practice as it relates to constipation or gastrointestinal disorders, join us on an upcoming course!

Dry Needling and Pelvic Health: Foundational Concepts and Techniques

Dry Needling and Pelvic Health 2: Advanced Concepts and Neuromodulation

Dry Needling and Pelvic Health: Pregnancy and Postpartum Considerations

References

- Forootan M, Bagheri N, Darvishi M. Chronic constipation: A review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(20):e10631. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010631

- Black CJ, Ford AC. Chronic idiopathic constipation in adults: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Med J Aust. 2018;209(2):86-91. doi:10.5694/mja18.00241

- Sharkey KA, Mawe GM. The enteric nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2023;103(2):1487-1564. doi:10.1152/physrev.00018.2022

- Spencer NJ, Hu H. Enteric nervous system: sensory transduction, neural circuits and gastrointestinal motility. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(6):338-351. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-0271-2

- Larauche M, Wang Y, Wang PM, et al. The effect of colonic tissue electrical stimulation and celiac branch of the abdominal vagus nerve neuromodulation on colonic motility in anesthetized pigs. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(11):e13925. doi:10.1111/nmo.13925

- Zhang C, Chen T, Fan M, et al. Electroacupuncture improves gastrointestinal motility through a central-cholinergic pathway-mediated GDNF releasing from intestinal glial cells to protect intestinal neurons in Parkinson's disease rats. Neurotherapeutics. 2024;21(4):e00369.

- Jacobson A, Yang D, Vella M, Chiu IM. The intestinal neuro-immune axis: crosstalk between neurons, immune cells, and microbes. Mucosal Immunol. 2021;14(3):555-565. doi:10.1038/s41385-020-00368-1

AUTHOR BIO:

Tina Anderson, MS PT

Tina Anderson (she/her) received her Master of Science in Physical Therapy in 2001 from Grand Valley State University located in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She graduated from Michigan State University in 1996 with a Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology. Tina specializes in treating patients with complex neuromusculoskeletal dysfunction including dysfunctions of the pelvic floor. Tina earned her dry-needling certification in 2006 and has been teaching dry-needling nationwide since 2008. Tina was integral in pioneering dry-needling techniques for the pelvic floor and surrounding neuroanatomical structures. She currently owns and operates a private physical therapy practice in Aspen, Colorado. Tina and her family, including their new “fur” child Beatrice, love living and playing in the Rocky Mountains!

Tina Anderson (she/her) received her Master of Science in Physical Therapy in 2001 from Grand Valley State University located in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She graduated from Michigan State University in 1996 with a Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology. Tina specializes in treating patients with complex neuromusculoskeletal dysfunction including dysfunctions of the pelvic floor. Tina earned her dry-needling certification in 2006 and has been teaching dry-needling nationwide since 2008. Tina was integral in pioneering dry-needling techniques for the pelvic floor and surrounding neuroanatomical structures. She currently owns and operates a private physical therapy practice in Aspen, Colorado. Tina and her family, including their new “fur” child Beatrice, love living and playing in the Rocky Mountains!

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./