In 2024, the Journal of Women’s and Pelvic Health Physical Therapy published an article on stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and parous runners. It specifically looked at functional lower extremity strength along with running mechanics. The study had 22 participants who performed functional strength tests, including a 30-second single-leg sit-to-stand test and a 10-minute treadmill run with a cadence assessment, and also filled out SUI questionnaires. The higher questionnaire scores had a positive correlation between increased ground contact times and slower cadences.

There was no correlation between the 30-second single-limb sit-to-stand test and higher SUI questionnaire scores. However, multiple other studies referenced in this article have shown increased SUI with decreased hip external rotation and abduction strength compared to those without SUI. The 30-second single-limb sit-to-stand test has not been validated as a good measure of hip strength at this time.

In the remote course The Runner and Pelvic Health by Leeann Taptich and Aparna Rajagopal, they will discuss running mechanics, faults of running including ground reaction forces, contact times, and cadence along with functional strength assessments that can be performed for parous female runners with reported SUI. Please join them on December 14, 2024 for this course.

The 2024 Summer Olympics this summer (July 26 - August 11) will showcase the most elite athletes from all over the world. We will watch these athletes perform at World and Olympic Record times in various running events from sprints to long distances. These athletes demonstrate above-average form and strength, allowing their bodies to perform at peak ability. While these individuals are far above average, there is still the risk of dysfunction, including pelvic floor dysfunction, that can occur as a result of poor running form and from lower extremity injuries. Poor form can affect even the highest-level runners.

Recently, I co-treated a 32-year-old patient who was 4 months postpartum, with a pelvic therapist. Before childbirth, the patient was an avid runner participating in multiple running events who ran distances from 5k to a marathon. Since giving birth, the patient had complaints of increased urinary urgency and increased urinary frequency, having to urinate 11-14x/day and a minimum of 2x during the night. The patient still had not returned to running due to poor bladder control. This patient’s running evaluation demonstrated the following:

- ·Running video analysis: overstriding, bilateral hip drop, increased vertical displacement, and a heel whip on the left side.

- ·Movement assessment of squat: increased lumbar lordosis and increased sacral counternutation uncontrolled.

- ·Movement assessment of pistol squat: bilateral hip drop and bilateral genu valgum

- ·Musculoskeletal assessment: decreased gluteus medius and maximus strength, decreased motor control of left greater than right hip rotators.

This patient was seen for a total of 7 visits over 4 months, receiving a combination of therapy focusing on the above deficits and pelvic therapy. By the end of physical therapy, the patient had no complaints of urinary frequency/urgency, demonstrated improved squat, pistol squat, and running form as well as significant gains in lower extremity strength.

This article was submitted by Aparna Rajagopal and LeeAnn Taptich. Both practitioners are based out of the Henry Ford Macomb Hospital in Michigan where Aparna Rajagopal, PT, MHS is the lead therapist of their pelvic dysfunction program, and Leeann Taptich DPT, SCS, MTC, CSCS leads the Sports Physical Therapy team. Michigan. They work very closely together at the hospital which gives them a very unique perspective of their patients. Aparna and LeeAnn instruct the Breathing and the Diaphragm course. This remote course explores how the diaphragm, breathing, and the abdominals can affect core and postural stability through intra-abdominal pressure changes.

COVID-19 has been a part of our vocabulary for almost 2 years now and has changed the world we live in. COVID-19 is a virus that affects the cardiovascular, digestive, urinary, and respiratory systems. We still do not have adequate evidence to guide our treatment of COVID -19 patients in their sometimes prolonged recovery phase. Research continues to be made available about the short and long-term effects of the virus on our bodies.

An example of a post-COVID-19 patient was a female with complaints of difficulty taking in a deep breath. She also reported that the physical act of breathing felt like a lot of work/effort. She had undergone all sorts of respiratory and cardiac testing and had been cleared from a medical standpoint. Upon talking to the patient, it was discovered that she wasn't complaining of shortness of breath/dyspnea.

Leeann Taptich DPT, SCS, MTC, CSCS is Co-Author of the new Herman & Wallace offering, Breathing and Diaphragm: Pelvic and Orthopedic Therapist. Leeann leads the Sports Physical Therapy team at Henry Ford Macomb Hospital in Michigan where she mentors a team of therapists. She also works very closely with the pelvic team at the hospital which gives her a very unique perspective of the athlete.

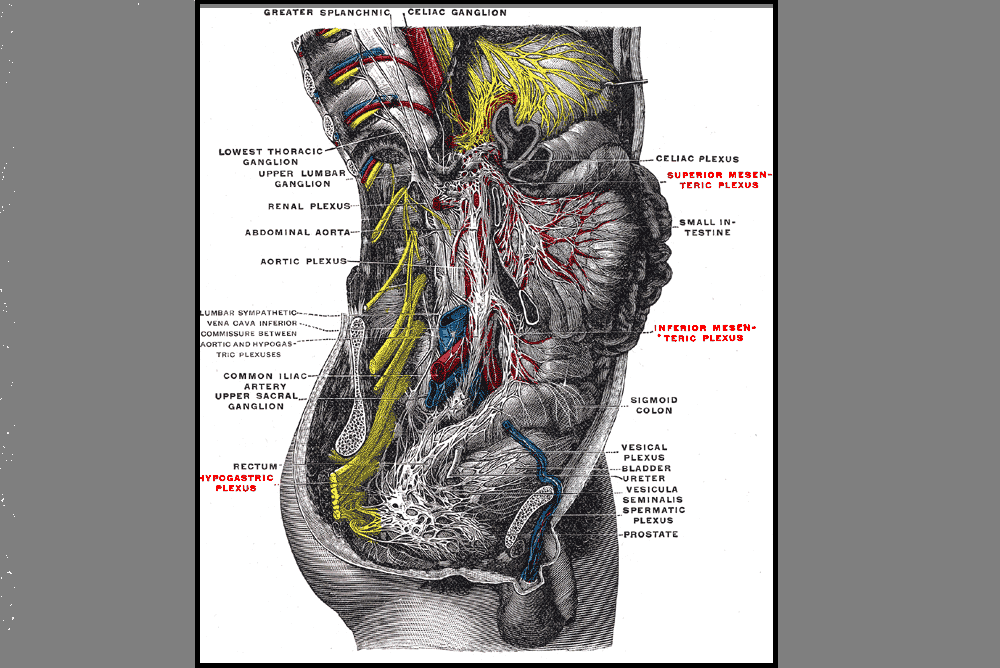

According to a paper from Manual Therapy, the thoracic spine is the least understood part of the spine, despite the huge role it plays in both movement and in regulation of our Autonomic Nervous System.1 Researchers found that the thoracic spine is the least studied of the three spinal regions; thoracic, cervical, and lumbar. I am frequently asked by fellow therapists for help in objectively assessing and treating the thoracic region which has led to the realization that even amongst experienced therapists the thoracic spine’s importance is less understood especially in terms of its function.

Anatomically, the thoracic spine along with the ribs and sternum provide a frame that supports and protects the lungs and heart. Despite the rigidity that is required to fulfill that function, the thoracic spine contributes significantly to a person’s ability to rotate.2