Tai chi is described in the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health’s (NCCIH) introduction as a “moving meditation” that originated in China as a martial art. Slow, gentle movements are combined with awareness and breathing. To watch a demonstration of a short form of Tai Chi Chuan click here. The health benefits of Tai Chi have been studied for a variety of conditions, including research funded by the NCCIH. Examples of topics and populations studied in funded research include bone loss in menopause, cancer-related issues such as fatigue, depression, fibromyalgia symptoms, osteoarthritis, cardiovascular function, and other types of arthritis.

A systematic review published last year in Complementary Therapies in Medicine discussed the effects of Tai Chi on quality of life for patients with chronic conditions. Included in the review were 21 articles meeting the criteria of being a randomized, controlled trial, including adults with chronic conditions such as arthritis, asthma, cancer, COPD, diabetes, heart disease, or AIDS, with Tai Chi being the primary intervention that was assessed by an outcome measure. Of the seven studies evaluated for the musculoskeletal system, conditions studied related to post-menopausal osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or fibromyalgia. Quality of life questionnaires were completed by the patients using self-assessment forms.

Although the limitations in the study included poor recording of length of time of Tai Chi sessions, or lack of documentation of home program use of the exercise, Tai Chi was found to be a safe and simple approach that improved self-reported functions, both physiological and psychological. An additional benefit that is pointed out in this research is that Tai Chi requires no equipment or particular facility in which to practice.

Integration of practices such as Tai Chi, yoga, Pilates, or other forms of activity are incorporated any many therapists’ treatment approaches, particularly when the therapist has personal experience or professional training in such approaches. Another way to learn how to incorporate useful skills from these types of approaches is to attend rehabilitation-directed training from someone who is both a practitioner of the approach as well as a therapist. The Institute offers a 2-day continuing education course titled Integrative Techniques for Pelvic Floor and Core Function: Weaving Yoga, Tai Chi, Qigong, Feldenkrais and Conventional Therapies taught by instructors who bring a wealth of knowledge about complementary approaches to rehabilitation. Bill Gallagher and Richard Sabel bring a wealth of experience to this course that is rich in lab practice. They offer their next course at the end of March in Boston. Click here for course details and registration.

Some of our patients will present with sacral or coccygeal pain, and the potential causes of this pain are numerous. One potential cause of sacrococcygeal pain is a Tarlov cyst, which occur when the nerve root sheaths are swollen and fill with cerebrospinal fluid. The condition can be very painful and can affect bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction due to the location of the nerves that may be compressed from the swelling. To learn more about the possible causes of Tarlov cyst formation, you can find a lot of information on the tarlovcystfoundation.org site. Symptoms might include low back and buttock pain, neurologic symptoms in the lower extremities, pain with sitting, and swelling over the sacral area. Pelvic dysfunction including bowel or bladder changes, rectal or vaginal pain, or painful intercourse can occur. The pain might worsen with forward flexion due to nerve tension, and pressure changes in cerebrospinal fluid can contribute to headaches or vision disturbances.

Unfortunately, most of our patients present with some or all of the above complaints, so how do we participate in the process of determining when the patient needs to return to a medical provider? In addition, these cysts might be discovered as an “incidental” finding on an imaging study, and the medical provider may complete further tests to determine if the cyst is causing the patient’s symptoms. The most important aspect of screening for dysfunction such as a Tarlov cyst, which can progress to significant neurologic impairment if symptomatic and eft untreated, is keeping track of our patient’s symptom progression and neurologic signs. Getting a baseline lower extremity neurologic screen for every patient with pelvic pain or dysfunction is an critical skill so that we can communicate any significant worsening or lack of progress to the medical provider. Such a lower extremity neurologic scan should include sensation testing, deep tendon reflexes, and signs such as Babinski and clonus tests.

Patients will also present to pelvic rehabilitation after having had a Tarlov cyst repair. Surgeries can include drainage of the cyst followed by use of a fibrin glue to occlude the cyst in hopes of preventing recurrence. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons points out on their website that surgery may not eliminate the patient’s symptoms, and care involving supervised pain management may be appropriate. From a rehabilitation standpoint, these patients may or may not be finding their way to a pelvic rehab practitioner. Is there a provider in your area who may be treating these patients and who is not aware that you have skills to offer? Interventions such as pain management strategies, modalities, movement therapy, manual therapy, treatment directed to neurodynamics, and general wellness education may all play a role in helping patients recover from procedures for Tarlov cysts.

To learn more about treatment of pain in the coccyx area, you can sign up for faculty member Lila Abbate’s Coccyx Pain Evaluation and Treatment continuing education course, with the next opportunity to take the class in Torrance, California, at the end of March.

Many of us in pelvic rehabilitation started out working exclusively with female patients and within the realm of urinary dysfunction. As our caseload broadened and the recognition that a "simple" case of urinary dysfunction was about as common as a "simple" ankle sprain, our education and clinical skills branched out to meet the needs of our patients. Many therapists had to extrapolate what they knew about women's anatomy and pelvic rehabilitation and apply that knowledge to men. (Even despite some therapists' insistence that their caseload should focus on women, the men who were desperate for care would show up anyway!) So what is different about men, and why is there a need to understand not only the common dysfunctions they face, but also how men tend to approach health care?

To begin with, men have significant barriers to healthcare, including lack of a primary caregiver. (Grant et al., 2012) Although men may have greater social privileges than women, that privilege also comes with social pressures to be more dominant, more in control and to be less emotional. (Fleming et al., 2014) These barriers and pressures may make it difficult for a man to seek the healthcare that can improve his state of well-being. Therapists can familiarize themselves with approaches to communication and providing support that fit within the context of the individual patient, allowing him to learn needed strategies while still maintaining a sense of empowerment.

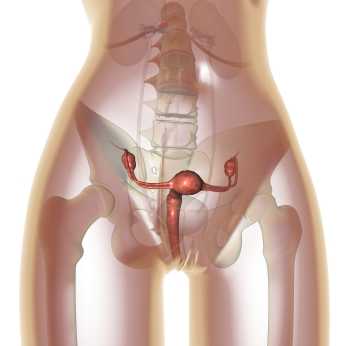

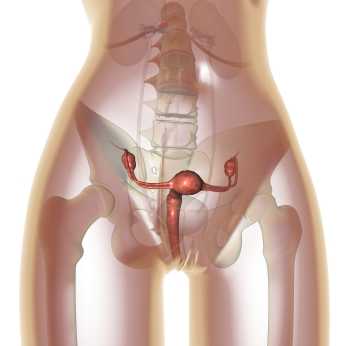

Men also tend to have different pelvic dysfunctions than women. Anatomically, a longer urethra means that men tend to suffer fewer urinary tract infections. Without the physiologic needs for childbirth, men are designed with a smaller pelvis, larger bony attachments for muscles, and decreased rates of prolapse and abdominal wall separation. Men do, however, tend to have higher rates of dysfunctions such as inguinal hernias, and may be more prone to rectal prolapse than rectocele. Prostate cancer, the most common cancer among men, can also lead to significant urinary and sexual dysfunction following surgery or other treatments. As pelvic rehabilitation providers, we want to be best prepared to answer questions about all domains in men's health, whether the concerns relate to bowel, bladder, sexual dysfunction or pain.

The Institute's continuing education course on Male Pelvic Dysfunction is new this year, with all lectures and labs revised. This course has been taught for many years, allowing the instructors to collect feedback about the needs of the therapists who treat men across the country (and around the world!) Because most therapists have not had the opportunity to learn the details of male anatomy that may influence pelvic dysfunction, this course includes anatomy lecture and palpation throughout the two days of training. Topics in the course are designed to cover issues in male continence, sexual function, prostate issues (both benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) and post-prostate cancer treatments), and male pelvic pain. Conditions such as epididymitis, scrotal and testicular pain, and Peyronie's are discussed, from the aspects of medical evaluation, rehabilitative evaluation and intervention, and from the available literature.

If you are already treating female patients, your knowledge will serve you well in the Male Pelvic Dysfunction course. If you are completely new to pelvic rehabilitation, this course will cover important basics such as internal (rectal) pelvic muscle assessment and skills for pelvic rehabilitation. The labs and activities have been re-designed to allow both the experienced and the new therapist to feel appropriately challenged regardless of skill level. If this is your year to increase your knowledge (and maybe your caseload) about men in pelvic rehab, you will have opportunities in March in Nashville and Denver in August to take the male course!

References

Fleming, P. J., Lee, J. G., & Dworkin, S. L. (2014). “Real Men Don't”: Constructions of Masculinity and Inadvertent Harm in Public Health Interventions. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1029-1035.

Grant, C. G., Davis, J. L., Rivers, B. M., Rivera-Colón, V., Ramos, R., Antolino, P., . . . Green, B. L. (2012). The men’s health forum: An initiative to address health disparities in the community. Journal of community health, 37(4), 773-780.

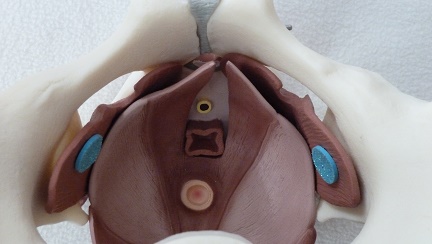

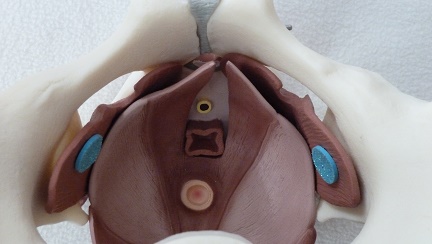

Measuring pelvic floor function and dysfunction is an emerging clinical science. Researchers and clinicians including Kari Bo, physiotherapist from Norway, have contributed tremendously to the field of pelvic rehabilitation. In an article by Bo and Sherburn published in the Journal of Physical Therapy, the authors describe methods of evaluating pelvic floor function as being divided into measuring of contraction ability (clinical observation, vaginal palpation, ultrasound, MRI, or electromyography (EMG)), and measuring of strength quantification (manual muscle test via vaginal palpation, manometry, dynamometry, or cones.) The authors state that while each method has their place in rehabilitation, each also has limitations. In addition to understanding the best methods for examining pelvic muscle function, we can also consider the techniques that are most useful in examining pelvic organ prolapse.

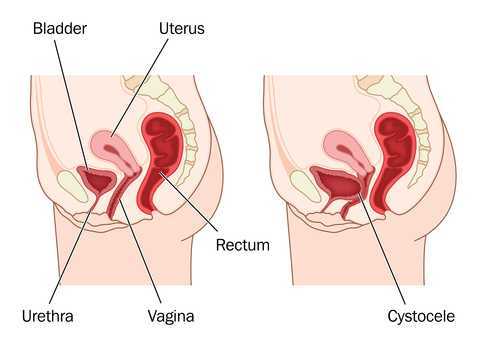

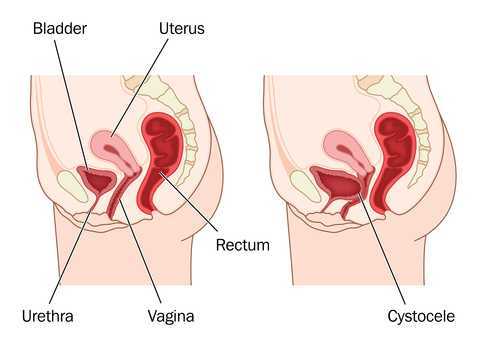

In standing, gravity exerts increased force on the tissues of the pelvis and pelvic floor, therefore, prolapse may be more easily and accurately identified in the standing position. Frawley and colleagues have pointed out that because the provocation of prolapse is higher in standing than in sitting for most patients, rehabilitation testing in standing may be more reflective of functional pelvic floor muscle activity. Research has also concluded that digital (using an examining finger) pelvic organ prolapse examination in supine is unreliable. In standing, however, the same article reports that quality of life and symptom impairment do correlate with digital pelvic floor muscle testing.

Although it has been established that physiotherapists can reliably utilize the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) protocol, POP-Q staging and ordinal scale staging (scoring on a 0-4 scale) have been found to be similar in identifying prolapse. This brings us to the question of how to clinically evaluate for pelvic organ prolapse in standing. Therapists use a variety of strategies for assessing a patient in standing, including:

- Ask patient to sit or squat over opening in table (you may or may not have such a table)

- Palpate digitally while patient is in standing position

- Use a mirror on the floor or hold a mirror under the patient's perineum

- Position yourself under the patient while testing

- Have patient sit on a bedside commode with the center piece open

- Ask the patient to stand on a table (consider safety of this option!)

While it may be useful to test patients for prolapse in supine, research points us to the need to also test patients in positions that will reflect the most significant symptoms. Considering the patient's functional needs as well as anatomic variations, this position may be in quadruped, prone, squatting, or standing, and we must figure out how to incorporate these functional positions into our training.

Are you eligible to become pelvic rehab certified?

The rigorous and psychometrically validated Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification (PRPC) will be offered for the third examination this year. You still have time to join the nearly eighty practitioners who have earn their letters! (Keep in mind that, different from a "certificate", this certification allows you to use the designation "PRPC" after your name, helping to distinguish you as an expert in pelvic rehabilitation. In case you are uncertain if you are a candidate to sit for the PRPC examination, check out some commonly-asked questions below.

Types of practitioners: Do I have to be a physical therapist?

You do not need to be a physical therapist in order to apply for the PRPC exam. What is required is that you have a license to practice the skills utilized in pelvic rehabilitation. Such a license may include physician (MD, DO, ND), registered nurse (RN), occupational therapist (OT), advanced registered nurse practitioner (ARNP), or physician assistant (PA-C). Any other provider can apply and will be examined on a case-by-case basis.

Coursework: Do I have to take certain Herman & Wallace courses?

There are no prerequisite courses that you need to take before registering for the examination. Most providers, in order to work with patients who have pelvic dysfunction, will take a variety of continuing education courses to round out their knowledge and skills for bowel, bladder, sexual and pelvic pain dysfunctions. Various providers will also have had differing training within their respective professional education and clinic experience.

Experience: How much pelvic rehabilitation experience do I need?

You must have 2000 hours of experience in pelvic rehabilitation within the past 8 years, with 500 of the hours occurring within the last 2 years.

Details: Where can I find more information?

All the details can be found on our website at the following link: https://hermanwallace.com/pelvic-rehabilitation-practitioner-certification. You can find sample questions, pricing of the exam and application, and even find some study resources!

Deadlines: By when do I need to register?

The registration cut-off date for the next exam in May of 2015 is April 1st. The sooner you get your application approved, the faster you can be connected to like-minded practitioners who want to study with you for the exam! This is the only certification that is specific to pelvic rehabilitation for men and women across the lifespan. Most who have taken an exam will tell you that while the exam is not "fun", the studying really steps up your clinical practice as you have a chance to broaden and deepen your knowledge and refine your skills. Good luck!

As a physical therapist I am continually amazed at the myriad of ways the parts of our bodies are connected (and even more so by our brain/body connections, but that is another blog post.) Take one of my favorite muscles for example, the obturator internus. This amazing muscle is known for its relationship to the hip as one of the external rotators, and it’s anatomy is impressive! What other muscle sharply turns ninety degrees from its attachment to its origin? The obturator internus traverses the inside of the pelvis and attaches mid-belly to an important tendon, the Arcuate Tendon Levator Ani (ATLA) , which becomes the means by which the obturator connects to the pelvic floor. (I love to show patients how their hip literally connects to their pelvis!) The ATLA connects with the Arcuate Tendon Fascia Pelvis which connects to the fascia supporting the bladder and urethra.

We know that in our patient who have pelvic pain too much tension or trigger points in the obturator internus can create symptoms of urinary urgency or frequency, pain in the bladder, vagina, rectum, abdomen, pelvic floor and hip. But what happens when the obturator internus is uptrained to treat women with stress urinary incontinence (SUI)? An article in the May/August 2014 Journal of Women’s Health looked at the role of strengthening the obturator internus and the adductors and compared the effects to working the pelvic floor for the treatment of women with SUI. The results were quite interesting.

This research was a pilot study comparing two randomly assigned groups of community dwelling women with SUI. A group of 12 completed resisted hip rotation (RHR) and a group of 15 completed pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). Each group exercised at home for six weeks with a weekly recheck. Outcome measures included subjective reports of improvement, leak frequency, and scores from the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) and the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI). The exercise routines were supposed to take about 5 minutes and be performed twice a day. Subjects were instructed to sit with good posture and with their feet on the floor. The pelvic floor muscle group performed 5-second holds for 20 reps followed by 20 quick contractions. The RHR group exercised by 1) rotating internally and externally with diaphragmatic breathing for 10 breaths , 2) 10 repetitions of resisted hip external rotation with a green band and 5 second work/rest cycle and 3) 10 repetitions of hip internal rotation/adduction against a 9 inch ball with the same 5 second squeeze and rest cycles.

The results of the study showed that BOTH groups had significant and equal improvement in outcome measures by the end of the six weeks, but that the RHR group showed improvements sooner than the PFMT group. The authors discuss the limitations of their study: small sample size, large ranges of participant ages, patients were not medically examined, outcome measures were subjective, and the pelvic floor group only received verbal instruction. This study was thought provoking to me for several reasons. First, it gives me a great platform to talk with my non-pelvic health colleagues about treating pelvic floor weakness dysfunctions with indirect pelvic floor treatment. Virtually any patient could sit and roll their legs in and out against resistance! This exercise could be easily incorporated into a routine for people with bladder leakage or at risk for bladder leakage. Secondly, we often see patients with non-functioning pelvic floor muscles. My typical protocol before discussing the treatment option of electrical stimulation is to uptrain (increase muscle activity) with hip rotation, adduction and transverse abdominus muscle exercises. I have often found that I don’t need to address the pelvic floor directly when the accessory muscles are appropriately engaged. This study points out the importance of muscles outside of the pelvic floor in providing support for continence.

Thirdly, can we extrapolate the benefit of resisted hip exercise into more functional or more challenging exercises for our high level athletes or moms who want to jump on the treadmill with their kids? Would this approach be helpful? I know many of us are already doing this. Could this idea be a future research project? Lastly, John Delancey published in an anatomy study of cadavers that the muscle fibers around the striated urethral sphincter decrease in density and number at a rate of 2% a year after the age of 35!!! The process might go a little faster with higher parity and slightly slower in women who have never been pregnant. Could this mean that our reliance on our accessory muscles increases with age? Perhaps using both pelvic floor and resisted hip strengthening will lead to improved outcomes in older women.

One reason I love to read research is because it gets my brain thinking not only about how interconnected our bodies are, but I also ask myself what else I want to know about this subject and how can this information be used. We may not have the research-validated information we want yet, but applying critical reasoning to our clinical practice is the first step in further understanding.

You can join faculty member Jennafer Vande Vegte at an upcoming intermediate PF2B course. Keep in mind that these pelvic floor continuing education courses sell-out months in advance! With courses on both coasts and in the middle of the US, hopefully you can find a location that works best for you!

When examining a patient clinically for pelvic wall relaxation or pelvic organ prolapse, we know that verbal cues given, position of the patient, time of day, bladder fullness, and other variables can affect the outcome of the prolapse evaluation. What about the number of attempts at bearing down or straining during the examination? Is one attempt at bearing down enough to provide clear information about the level of descent or relaxation in the pelvic walls or organs? If research based on dynamic MRI's is any indication, the answer may be "no."

40 women with an anterior wall prolapse that extended at least 1 cm beyond the hymenal ring were evaluated with dynamic MRI scans. The subjects were instructed in and evaluated for their ability to properly bear down prior to the scans. Between the first, second, and third maximal efforts at bearing down, or Valsalva, bladder descent was measured during dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In 95% of the women, prolapse measurements were more significant by the third effort at bearing down. 40% of the women demonstrated more than a 2 centimeter increase in prolapse from the first to third attempt at Valsalva. In this research study the mean age of the subjects was about 60 years old, and 80% of the women were Caucasian. Childbirth history averaged 2 vaginal births and eight of the women had a prior hysterectomy.

While the authors discuss the value of using this diagnostic information to create improved dynamic MRI protocols, there may also be implications for the pelvic rehabilitation provider. When we are assessing for the integrity of the pelvic supporting structures, are we getting a reliable effort from the patient? Are we asking for more than one attempt at bearing down? In addition to considering relevant issues like the time of day or the position of the patient during an examination, we can also consider the number of times that the testing is completed. If we ask for only one attempt at bearing down, perhaps we are not being provided with the most accurate information. What we do with that information is the next important step in developing a plan of care or communicating with the referring provider. In the Pelvic Floor Level 1 (PF1) continuing education course, therapists learn how to assess for pelvic organ prolapse, and in the PF2B course therapists learn additional information about the fascial layers that, when not intact, can contribute to pelvic organ displacement. Providing interventions that address myofascial dysfunction and functional use patterns of the trunk and limbs can help a woman overcome symptoms of prolapse, and working together with medical providers to help women with prolapse can be very rewarding.

Authors Yadav, Narang, and Kumaran in a recent review on psychodermatology report that a significant portion of patients who seek care from a dermatologist has "…an underlying psychiatric or a psychological problem that either causes or exacerbates a skin complaint." The relationship between the mind and the skin may have their link in embryology, with brain and skin sharing development from the ectoderm's end plate, according to the linked article. Psychodermatologic disorders are categorized by Yadav and colleagues into psychophysiological disorders (skin disease is affected by the patient's psychological state), primary psychiatric disorders (skin complaints are secondary to a psychological pathology) or a disorder of dermatological beliefs (rare occurrence of incorrect belief that skin is infested.) For a clinical example of psychophysiologic skin issues, we can consider the affect that stress can have on creating skin disruptions from the herpes virus. Primary psychiatric disorders might include anxiety or depression, comorbidities from which many of our patients suffer.

In addition to pointing out the necessary medical management of any skin condition, the article notes that there are other recognized approaches that can assist a patient in healing well and in avoiding exacerbations. For example, biofeedback training is listed as a helpful modality for hyperhidrosis, Raynauds phenomenon, dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus, urticaria, and post herpetic neuralgia. Certainly many of our patients are dealing with these and other comorbidities, and many therapists are also aware of the value in teaching stress-management techniques such as breathing, using biofeedback, and avoiding catastrophizing. The article concludes the following: "Awareness and pertinent treatment of psychodermatological disorders among dermatologists will lead to a more holistic treatment approach and better prognosis in this unique group of patients."

In addition to being helpful for dermatologists, this information may serve pelvic rehabilitation providers and their patients. For example, if mast cells in the skin can be impacted by stress hormones, can this same stress affect through neuroendocrine pathways the skin of the genital area? Research in conditions of chronic pelvic pain have asked this question, in relation to mast cells and other mediators of potential pain sources, with inconclusive results. Regardless of the source of the pain, this article reminds us to look beyond the matter to the mind, and to be helpful to our patients in considering the effects of either. If a patient presents with a skin condition, can we direct him or her to a dermatologist or discuss the potential benefits of managing stress with specific strategies to minimize the impact of the skin issue? If you are interested in learning specific strategies in stress management, check out the Institute's continuing education courses on Meditation as well as on Mindfulness-Based Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain. We are still scheduling these courses this year- if your facility would like to host either (or both!) of these courses, please contact us at the Institute.

In women who have endometriosis, ablation procedures are commonly completed to destroy endometrial tissue lining the uterus. A goal of ablation is to disrupt severe bleeding that can lead to other conditions including anemia. Research published in last month's Obstetrics & Gynecology identified the risk factors for pain and subsequent hysterectomy following ablation procedures for endometriosis. Of 300 women, 270 completed follow-up, and the resultant data was reported:

- -23% developed new onset or worsening pain after the ablation

- -19% proceeded to hysterectomy

- -a history of dysmenorrhea increased the risk of developing pain by 74%

- -a history of tubal sterilization increased the risk of developing pain by > 50%

- -women of white race were 45% less likely to develop pain

- -a history of cesarean delivery more than doubled risk of hysterectomy

- -uterine abnormalities such as leiomyoma, adenomyosis, thickened endometrial strip, or polyps quadrupled the risk for hysterectomy

For the nearly 20% of these women who had a hysterectomy after ablation therapy, the most common indication for the hysterectomy was pain. Regarding the increased risk of pain after ablation in non-white women, the authors proposed the higher rates of leimyomatous uteri in African American women (largest population of non-white women in the study) as a source. Because pain is a potential complication of endometrial ablation, the authors of this article recommend that providers consider patient characteristics when educating patients about the potential benefits and risks of the procedure.

Although in pelvic rehabilitation we do not counsel for or against surgical procedures, knowledge of the potential risk factors for our patients who have had or who are having a uterine ablation can assist in our screening and interventions. If a patient asks our opinion about uterine ablation, pointing out research such as the linked article may help her discuss pros and cons with us and with her providers. The need for patients to understand the potential side effects of a uterine ablation and to actively manage her recovery may be important in avoiding hysterectomy, if that is the patient's goal. Endometriosis is one of the main topics in a new course offered by faculty member Michelle Lyons. The new continuing education course "Special Topics in Women's Health: Endometriosis, Infertility, and Hysterectomy" will be offered in March in San Diego and the Chicago area in May.

Catastrophizing is a buzzword in relation to pain, but what does it really mean for our patients and for our plan of care? Catastrophizing, according to Iwaki and colleagues is a maladaptive response to pain, with research supporting the idea that level of catastrophizing behavior may predict a patient's level of function. A terrific blog post on the Psychology Today website by Alice Boyles, PhD, translates the term into everyday symptoms of this behavior. She describes catastrophizing as having 2 parts: predicting a negative outcome, and then concluding that if the negative outcome happens, this would be a catastrophe. Imagine our patients who develop a painful condition, and then jump into a "worst case scenario." A patient who develops pelvic pain may think "I will never get rid of this pain", and then perhaps, "I will never have a partner and a healthy sex life."

Several prior blog posts on the Herman & Wallace website have specifically addressed different conditions and the role of catastrophizing. Some of the posts include the following topics:

Catastrophizing in Male Chronic Pelvic Pain

Lumbopelvic Pain and Catastrophizing in Pregnancy

Psychological Factors in Female Pelvic Pain

The study by Iwaki and colleagues also reported on subdomains of catastrophization and reported that the trait of helplessness was predictive of pain intensity, pain interference and depression, and that magnification of symptoms was predictive of anxiety. Regardless of the extent to which catastrophization impacts healing, being able to reframe pain and healing for our patients becomes a necessity so that the patient can focus on the steps involved in healing. The Institute now offers several continuing education courses designed to teach the therapist skills to address catastrophization including Meditation for Patients and Providers, and Mindfulness-based Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain.