George Thiele, MD, published several articles relating to coccyx pain as early as 1930 and into the late 1960's. His work on coccyx pain and treatment remains relevant today, and all pelvic rehabilitation providers can benefit from knowledge of his publications. Thiele's massage is a particular method of massage to the posterior pelvic floor muscles including the coccygeus. Dr. Thiele, in his article on the cause and treatment of coccygodynia in 1963, states that the levator ani and coccygeus muscles are tender and spastic, while the tip of the coccyx is not usually tender in patients who complain of tailbone pain. The same article takes the reader through an amazing literature review describing interventions for coccyx pain in the early 20th century.

Examination and physical findings, according to Dr. Thiele, include slow and careful sitting with weight often shifted to one buttock, and frequent change of position. He also describes poor sitting posture, with pressure placed upon the middle buttocks, sacrum, and tailbone. Postural dysfunction as a proposed etiology is not a new theory, and in Thiele's article he states that poor sitting posture is "…the most important traumatic factor in coccygodynia…" and even referred to postural cases as having "television disease."

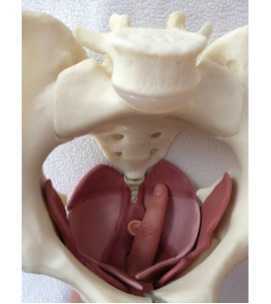

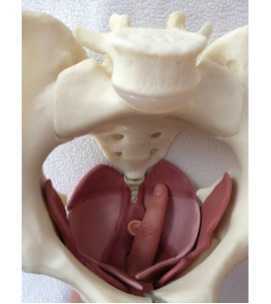

In reference to treatment, Thiele suggests putting a patient in Sims' position (left lateral side lying or recumbent position), and placing the gloved index finger into the rectum with the thumb over the coccyx externally, palpating the coccyx between the thumb and index finger. The finger is then moved laterally, in contact with the soft tissues of the coccygeus, levator ani, and gluteus maximus muscles. The finger is moved with moderate pressure "…laterally, anteriorly, and then medially, describing an arc of 180 degrees until the finger tip lies just posterior to the symphysis pubis." The massaging strokes, applied to a patient's tolerance, are applied 10-15 repetitions on each side with the patient being asked to bear down during the massage strokes. Dr. Thiele recommended daily massage 5-6 days, then every other day for 7-10 days, and gradually less often until symptoms are resolved.

Thiele's massage for coccygodynia is one excellent tool in the treatment of coccyx pain. For a comprehensive view of coccyx pain, check out faculty member Lila Abatte's Coccyx Pain Evaluation and Treatment continuing education course, coming up in New Hampshire in September!

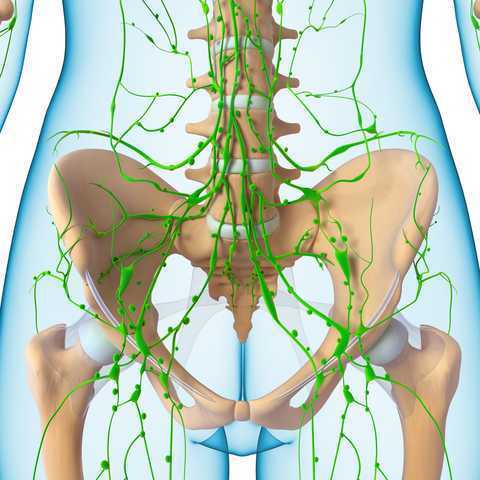

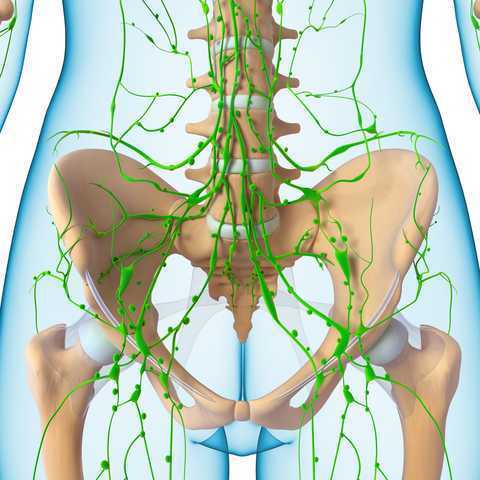

An interesting study assessed the ability of fluorescence imaging to measure the benefits of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD a key component of complete decongestive therapy (CDT). Lymphatic dysfunction, often developing into lymphedema, affects a significant population of our patients who undergo treatment for breast cancer or pelvic cancer. Complete decongestive therapy includes manual lymphatic drainage, compression bandaging, therapeutic exercise, and specific skin care techniques. A theory describing the beneficial effects of MLD, as explained in this article, is that MLD stimulates a contractile or "pumping" mechanism within the superficial lymphatic system.

Although effects of MLD can be measured by limb volume assessment, this study aimed to investigate if in fact contractile function is improved. The investigators used near-infrared fluorescence, or NIR fluorescence, to measure "…the apparent propulsive lymph velocities..and…the period or time of arrival between successive propulsive events." Twelve subjects diagnosed with Grade I or II unilateral lymphedema and 10 controls were included in this research and were treated by a certified lymphedema therapist. The manual lymphatic drainage preparatory protocol for an involved upper extremity included lymphatic massage to the cervical lymph nodes x 5 minutes, then the neck, axillary region of the contralateral arm, and the ipsilateral inguinal region. Lower extremity MLD also started at the neck, then treatment was directed to the contralateral inguinal nodes and ipsilateral axillary nodes. The control subjects received massage to the neck for 3 minutes, bilateral axillary region massage x 5 minutes or bilateral inguinal regions, depending on if the upper or lower limb was imaged in the study. The appropriate limb was then treated with MLD massage techniques.

Prior to and after the treatment, images were collected that allowed the researchers to visualize the imaging contrast agent that was injected through intradermal route into the patient's upper or lower extremities. The results of the study, although limited by statistical power by the low number of subjects, demonstrated that after the manual lymph drainage, in subjects and in controls, treatment had the potential to improve lymph transport. Despite the overall evidence of potential for improvement, there were two subjects in the upper extremity lymphedema group who did not show an improved lymph transport after treatment. One of these subjects also did not respond to MLD and bandaging treatment that followed for six weeks after the fluorescence study. In the lower extremity treatment group, overall apparent lymph velocity and a decrease in the period between propulsive events was noted. The authors state that NIR fluorescence could be utilized to help predict patients who may benefit from manual lymph drainage. The imaging may also help identify functioning lymphatic vessels towards which the therapist can direct manual techniques for draining the limb effectively.

While this study was directed towards the lymphatic dysfunctions of the limbs, what does a pelvic rehabilitation therapist need to know when treating dysfunctions of lymph in the pelvis? Lymphatic function can easily be interrupted following surgeries, or radiation for pelvic cancers, or even following orthopedic injuries. Join Debora Hickman at her continuing education course Manual Lymphatic Drainage for Pelvic Pain in San Diego next month to learn technique in applying MLD for the pelvis!

Do women who have pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy have altered gait patterns? The answer to this question was the aim of a study published in the European Spine Journal in 2008 by Wu and colleagues. Pelvic girdle pain, defined by Vleeming and colleagues as "…a specific form of low back pain (LBP) that can occur separately or in conjunction with LBP…" has been estimated to occur as often as 50% in pregnancy. (Gutke et al., 2006) Unfortunately, of the women who develop pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy, research has demonstrated that 1 in 4 women will develop chronic postpartum pain. (Ostgaard et al., 1991) Pelvic girdle pain can appear as mild, moderate, or severely debilitating, and can be confirmed using provocation tests such as the posterior pelvic provocation test and the active straight leg raise (ASLR). Our role as pelvic rehabilitation providers is critical in minimizing the functional impact of pelvic girdle pain during and following pregnancy.

In regards to gait changes in women who present with PGP in pregnancy, in general, walking velocity is reduced, is negatively correlated with fear of movement, and there are changes in thorax and pelvic rotations. In the study by Wu and colleagues, kinematics were examined in 11 women with PGP and 12 pelvic-healthy controls. Findings within the patients with PGP include that transverse segmental rotation amplitudes were larger, and peak thorax rotation occurred earlier in the stride cycle at higher velocities. The authors suggest that this change in thorax rotation may aid in avoiding excessive spinal rotations caused by larger segmental rotations, or in limiting the motion in the lumbopelvic region.. They further describe that in healthy subjects, pelvic rotations are relatively out-of-phase with the lower extremities at lower velocities, and more in-phase during higher velocities, and that this pattern may be altered in the presence of PGP.

What is the clinical relevance of this information? The primary author in the study also reported on postpartum pelvic girdle pain and gait, and found that changes in trunk and pelvic coordination persist in the postpartum period, and that an individual may employ a variety of adaptive strategies to deal with pain and possibly weakness during gait. What changes in movement strategies does a patient present with in early postpartum versus late postpartum? Does a woman, if she has never been offered rehabilitation, spontaneously recover from these gait adaptations? How does fear of movement and pain-avoiding strategies affect her movement even decades later? In the absence of having gait laboratories, clinical observation of walking at varied speeds can identify patterns of movement that may be aggravating a spinal or pelvic condition. Does she rotate her trunk with a reciprocal limb pattern? Does she limit rotation at the pelvis and overcompensate in the thoracic spine? Observation of patterns that fit clinical symptoms may assist in avoiding persisting gait alterations. Early recognition of pelvic girdle dysfunction in pregnancy and throughout the postpartum period may allow her to avoid compensations in gait that contribute to musculoskeletal dysfunction. To learn about more exciting concepts in postpartum recovery, come to the Care of the Postpartum Patient in Houston in June or in Chicago area in September!

References

Gutke, A., Östgaard, H. C., & Öberg, B. (2006). Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in pregnancy: a cohort study of the consequences in terms of health and functioning. Spine, 31(5 E149-E155.

Ostgaard, H. C., Anderson, G. B. J., & Karlson, K. (1991). Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy: A review. Spine, 16(5 549-552.

Vleeming, A., Albert, H. B., Östgaard, H. C., Sturesson, B., & Stuge, B. (2008). European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal, 17(6 794-819.

During a pelvic muscle assessment, patients who have pelvic pain or other dysfunction that includes pelvic floor muscle tenderness will often ask the pelvic rehabilitation practitioner the following question: "Doesn't everyone have tenderness if you push on the muscles like that?" The answer should be "no," and we have research to support this claim. While it may seem incredibly simple to a pelvic rehabilitation provider that a "healthy muscle does not hurt" and that in order to optimize muscle function, the length-tension curve should be optimized, this knowledge is not universally understood by most patients. Tenderness, especially if severe or if the intensity of the discomfort inhibits a healthy muscle contraction, can be eased so that a patient can learn to appropriately contract and relax the pelvic floor muscles.

While logical to rehabilitation providers, the concept that healthy muscles are typically devoid of significant tenderness must be well-established if we wish patients, providers, and payor sources to join in our belief that diminishing such tenderness can be a marker of progress. (Of course we keep in mind that function trumps tenderness, especially when a person has no functional limitations despite presenting with muscle tension or tenderness.) Researchers have aided our profession in establishing that significant muscle tenderness is not present in young, healthy, asymptomatic patients.

In research published last year, Kavvadias and colleagues assessed pelvic floor muscle tenderness in 17 asymptomatic, nulliparous female volunteers (mean age 21.5 years with results indicating low overall pain scores. The authors also aimed to examine inter-rater and test-retest reliability of specific muscle tenderness testing using a visual analog scale (VAS) and a muscle examination method recommended by the International Continence Society (ICS) over 2 testing sessions. This study used a cut-off score of 3 or less on the 0-10 VAS to determine clinically non-significant pain. Inter-rater and test-retest reliability was reported as good to excellent for palpation to the posterior levator ani, obturator internus, piriformis muscle, and for pelvic muscle contraction, yet found to be poor to fair for pelvic floor muscle tone and anterior levator ani palpation. Resulting scores on the VAS were less than 3 for all muscles tested, leading the investigators to conclude that in nulliparous women aged 18-30 who have no lower urinary tract (LUT) symptoms or history of back or pelvic pain, tenderness "…should be considered an uncommon finding."

While this research is in moderate contrast to some research cited in the report, the authors point out that the exclusion criteria and the ages of the women were more narrow in their studied population. Other authors such as Montenegro et al. (2010) have also reported a low prevalence of pelvic muscle tenderness in healthy volunteers (4.2%) whereas Tu et al. reported a high prevalence of tenderness (75%) in women who present with chronic pelvic pain. For male patients, Hetrick et al. concluded that patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome, or CPPS, have more pain and tension in pelvic and abdominal muscles than men without pain.

The value of research that establishes markers of health in tissues relating to function cannot be underestimated within the realm of pelvic rehabilitation. If we propose or document that reducing tender points, tension and muscle dysfunction is valuable for our patients, research that creates a baseline of non tenderness in patient populations is needed. The research from Kavvadias and colleagues assists our cause, as we can put this information together with other valuable modes of intervention to address pelvic muscle dysfunction within a holistic model of care. If you are interested in discussing further research about pelvic muscle tension, tenderness, and muscle releases, check out faculty member Ramona Horton's Myofascial Release for Pelvic Dysfunction, taking place next in Dayton, Ohio, this June.

Treating patients who have chronic pelvic pain is challenging for many reasons. The nature of chronic pain in any body site often means that the patient has a multifactorial presentation that requires a team approach to interventions. And because the pelvis also contains the termination of several body systems such as the urologic, reproductive, and gastrointestinal, there exists potential for addressing a musculoskeletal issue that is masking a medical issue which requires intervention by a medical provider. The phrase "When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail" can be applied to patient care for any discipline. When a patient presents with chronic pelvic pain, pelvic rehabilitation therapists can usually find tender pelvic muscles to treat. Is the pelvic muscle tenderness from guarding due to visceral pain or infection?

In a 2013 article in the journal General Practitioner, Dr Croton describes red flag symptoms in acute pelvic pain. These include pregnancy, pelvic or testicular masses, and vaginal bleeding and/or pain in postmenopausal women. During the history taking, patients can be asked about menstrual patterns, possibility of pregnancy, and sexual history. Further medical evaluation may include a pregnancy test, ultrasound, laparoscopy, and urine tests to rule out infection. While the above is not an exhaustive list, it reminds the pelvic rehabilitation provider to always keep in mind the potential for medical evaluation and intervention. Once a patient has been deemed to have "only chronic pelvic pain," a new, equally challenging list emerges: is the pain generated by an articular issue, myofascial dysfunction, neuropathy, psychological stress, or postural pattern? Is the pain local, such as in the pubis symphysis or in the sacroiliac joint ligaments, or are the symptoms referred from a nearby structure, such as the abdominal wall or the thoracolumbar junction? And what are the best methods to examine in a systematic way the various theories about the origins of a patient's pain?

Peter Philip has created a course to provide answers to the above questions. He combines skills in both orthopedics and manual therapy, and pulls from an extensive knowledge about pelvic pain and differential diagnosis which was the research topic of his Doctor of Science degree. Peter's course provides clearly instructed techniques in anatomical palpation, spinal and joint assessment, and he also instructs in how the nervous system and cognition can impact a patient's perception of pain. The course will be offered at the end of this month in Seattle- don't miss this chance to refine skills in differential diagnosis for chronic pelvic pain!

Concepts in "core" strengthening have been discussed ubiquitously, and clearly there is value in being accurate with a clinical treatment strategy, both for reasons of avoiding worsening of a dysfunctional movement or condition, and for engaging the patient in an appropriate rehabilitation activity. Because each patient presents with a unique clinical challenge, we do not (and may never) have reliable clinical protocols for trunk and pelvic rehabilitation. Rather, reliance upon excellent clinical reasoning skills combined with examination and evaluation, then intervention skills will remain paramount in providing valuable therapeutic approaches.

Even (and especially) for the therapist who is not interested in learning how to assess the pelvic floor muscles internally for purposes of diagnosis and treatment, how can an "external" approach to patient care be optimized to understand how the pelvic floor plays a role in core rehabilitation, and when does the patient need to be examined by a therapist who can provide internal examination and treatment if deemed necessary? There are many valuable continuing education pathways to address these questions, including courses offered by the Herman & Wallace Institute that instruct in concepts focusing on neuromotor coordination and learning based in clinical research.

One article that helps us understand how the trunk can be affected by the pelvic floor was completed in 2002 by Critchley and describes how, in the quadruped position, activation of the pelvic floor muscles increased thickness in the transversus abdominis muscles. Subjects were instructed in a low abdominal hallowing maneuver while the transversus abdominis, obliquus internus, and obliquus externus muscle thickness was measured by ultrasound. While no significant changes were noted in obliques muscle thickness, transversus abdominis average measures increases from 49.71% to 65.81% when pelvic floor muscle contraction was added to the abdominal hollowing. Clinical research such as this helps us to understand how verbal cues and concurrent muscle activation may affect exercise prescription.

A collection of clinical research concepts such as the article by Critchley is valuable in connecting points of function and dysfunction for patients with trunk and pelvic conditions- a large part of many clinicians' caseloads. The Pelvic Floor Pelvic Girdle continuing education course instructs in foundational research concepts that tie together the orthopedic connections to the pelvic floor including lumbopelvic stability and mobility therapeutic exercises. Common conditions such as coccyx pain and other pelvic floor dysfunctions are instructed along with pelvic floor screening, use of surface EMG biofeedback, and risk factors for pelvic dysfunction. If you would like to pull together concepts in lumbopelvic stability with your current internal pelvic muscle skills, OR if you would like to attend this course to learn external approaches, you can sign up for the class that takes place in late September in Atlanta.

Lumbopelvic pain is a common diagnosis in pregnancy that can be challenging for both the patient and the provider. A recent study assessed the effectiveness of 10 weeks of Hatha yoga in women between 12-32 weeks of gestation. 60 pregnant women ages 14-40 were divided into two groups, with the intervention group being guided in yoga exercises, and the control group instructed in postural activities. Nine pregnant women in the yoga group and six women in the control group were lost to withdrawal, obstetric complications, or refusal to participate. Excluded were women with twin pregnancies, medical restrictions, women using analgesics or those participating in physical therapy. Outcomes included a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) to measure pain intensity, and tests of lumbar and posterior pelvic pain. Lumbar provocation tests used in the study included trunk flexion and circumduction, paraspinal muscle palpation, and pelvic tests included the posterior pelvic pain provocation test.

Yoga intervention included weekly one hour sessions including 34 poses. The sessions focused on, in this order, breathing and joint warm-ups (10 minutes), poses and breathing exercises (40 minutes), and meditation and relaxation (10 minutes.) Pain intensity was assessed at the beginning and end of each session. Control group participants were instructed in typical postural changes during pregnancy as well as suggested postural support for various positions.

Results of the research include lower pain scores in the yoga group, with the authors concluding that yoga is an effective intervention for women who have pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. A final VAS score of no pain, or "0" was reported in 71% of the yoga group and in 21% of the control group. The women in this study also reported emotional benefits of tranquility, lowered stress, "an easy mind," mental balance, and increased sense of closeness to the baby. While the lumbar provocation tests improved in both groups in response to intervention, pelvic girdle provocation tests remained positive in both groups at conclusion of the study even in those who had lowered pain scores.

This brings up interesting questions about the nature of the causative factors for the patient's pain. Also of interest is that in the control, or "postural orientation" group, lumbar provocation tests were improved even when reports of pain were not noted. You can discuss this research and more at the upcoming Yoga for Pelvic Pain course taking place in California in March with Dustienne Miller, yoga therapist and physical therapist.

Throughout the Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain created by the European Association of Urology, the recognition of anxiety and depression as a concomitant symptom of chronic pelvic pain is made. Various types of pelvic dysfunctions have been demonstrated to have an association with anxiety and depression, including urethral pain, chronic pelvic pain, anorectal disorders, and sexual dysfunction. While a first line of medical treatment for patients who complain of neuropathic pain type, according to the Guidelines, is the prescribing of antidepressants, there are other interventions identified in the literature for alleviating anxiety and stress related to chronic pain. One of the studied interventions for pain, anxiety, and stress is yoga.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis for yoga and low back pain (which is also a common comorbidity of pelvic pain) yoga was found to have "…strong evidence for short-term effectiveness and moderate evidence for long-term effectiveness…" and the study concludes that yoga can be recommended for patients who have chronic low back pain. In this review of ten randomized controlled trials including 967 subjects with chronic low back pain, no serious adverse events were reported. A report in the journal Alternative Medicine Review states that yoga, which may be considered an adjunct therapy for stress and anxiety, is supported by good compliance among patient populations and a lack of drug interactions. The same study states that better research is needed before strongly recommending yoga for the specific purposes of reducing anxiety and stress. The current research is plagued with common statistical challenges: lack of a control group, variations in studied physiological markers, lack of validated scales, and heterogenous study populations.

For the pelvic rehabilitation provider, having a working knowledge of common yoga terminology and postures can assist in modification or adaptation of a patient's current routine. In addition, learning to apply yoga concepts and postures such as breathing, trunk and pelvic coordination, soft tissue lengthening within a patient's comfort can add to a pelvic rehab provider's toolbox. There is room for you to join Dustienne Miller, physical therapist and yoga instructor, in California at the Yoga for Pelvic Pain course. Contact the Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute if you have any questions about this continuing education course.

In our weekly feature section, Pelvic Rehab Report is proud to present this interview with newly certified practitioner Amy C. Sanderson, PT, OCS, PPRC.

(1).jpg)

Describe your clinical practice.:

I am a co-owner of a private physical therapy practice in the Spokane, Washington area. We currently have 3 clinics and staff 14 providers overall. I have been an Orthopaedic Certified Specialist since 1996, and our clinic is primarily an orthopedic setting. We do, however, provide several specialties, including Pelvic Rehab, Vestibular Program, and Video Gait Analysis for athletes.

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

I have been practicing since 1993 and began a Women’s Health program in 1994 at a previous place of employment. When I had interviewed for the position of a staff physical therapist for this clinic, I was asked if I would be interested in starting any new programs for the company. The manager had recommended that I develop a Women’s Health program. Truthfully, I had not heard of Women’s Health in the early 90’s, but I really wanted the job, so I said “absolutely!” I figured that I was a woman and I knew some things about health, so how hard could it be. Countless hours of continuing education and several years of marketing to the local physicians and community, we have now built our Pelvic Rehab program up to 3 physical therapists providing treatment to all of our clinics in the Spokane, Washington area.

What patient population do you find the most rewarding in treating and why?

I have enjoyed the patients who are experiencing sexual pain disorders for the past 15 years and have found this to be the most rewarding. Several times, I have been contacted after the birth of children to be told how grateful the couple has been to achieve such a life experience. Most recently, I received an email from a patient whom I had not seen in 3 years because she wanted to let me know that she and her husband were finally able to achieve intercourse after several years of counseling and my help with physical therapy. It is extremely gratifying to know that we can make a difference in peoples’ lives.

What motivated you to earn PRPC?

I have been practicing for greater than 20 years, including treating patients with all types of pelvic conditions, and after so many years, I wanted to challenge myself to see if truly what I was doing as a practitioner was effective, appropriate, and up to date. I decided that reviewing my education, seeking further education, and testing would be an effective way to do so. I felt that as I was preparing for this exam, I was able to realize that my treatment techniques are effective and appropriate. I am extremely grateful to the Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute for providing such great instructors to teach these skills.

Learn more about Amy C. Sanderson, PT, OCS, PPRC at her Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner bio page. You can also learn more about the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification at www.hermanwallace.com/certification.

A recent on-line survey queried fourty-four Obstetrician-Gynecologists (OB-GYNs) in British Columbia to learn more about the needs of physicians who treat women who have endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain (CPP). Physicians reported that women who present with endometroisis or chronic pelvic pain usually require more visits than other patients, for reasons including medical and pain management, lack of a clear diagnosis, and lack of improvement in condition. Evaluation techniques utilized by the physicians often included laparoscopy and ultrasound, and despite these practices, the OB-GYNS reported challenges in making a diagnosis or successfully treating their patients with CPP. In fact, survey results indicated that 5% of the respondents were able to diagnose a patient for a cause of pelvic pain in > 70% of patients. Most of the physicians reported that less than half of the women treated had a good response to interventions. Although the highest rate of referral for these providers was to another OB-GYN specializing in pelvic pain, nearly 60% of the time a referral to physical therapy was reported.

Although some of the narrative comments encountered in this survey were positive, including one physician's report of having "…good success with physiotherapy…", more often the providers expressed frustration and annoyance when faced with not only the challenges of diagnosis and treatment, but also the poor compensation and the longer visits required for counseling and teaching of patients. In addition to wanting more clear guidelines on diagnosis and management of female CPP, physicians expressed interest in having group educational sessions for patients, and more resources such as educational brochures on self-management for patients.

How can pelvic rehabilitation providers fill in this knowledge gap? I recall asking a referring provider if he was pleased with his patients' rehabilitation outcomes, and he expressed such a relief that I was taking the "dregs of the practice." He meant nothing disparaging about the patients themselves, he explained, just that when these patients walked in the door he felt a sinking feeling because he did not know what to do for them. Now, he reported, these same patients were returning from a pelvic rehabilitation referral and excitedly reporting on progress they had made. So many physicians and other referring providers still do not understand the scope of the patient populations that we can treat in pelvic rehabilitation. We can provide a necessary bridge between the challenge of diagnosing and medically treating chronic pelvic pain and the rehabilitation approach that addresses the chronic pain issues. Differential diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain from a rehabilitation standpoint is a skill set that every therapist must continually improve upon. If you are interested in learning more about these skills, sign up for faculty member Peter Philip's continuing education course Differential Diagnostics of Chronic Pelvic Pain next month in Connecticut.

(1).jpg)