So often, we think of vulvodynia as a condition of the skin. And it is….kind of. Vulvodynia is a long-term pain (or burning, discomfort, or itching) that is present in the outer genitals, also known as the vulva. This condition is defined as a discomfort that has lasted longer than 3 months. The symptoms of vulvodynia can vary. In some patients, it is provoked (brought on by touch or stimulation), and in some cases, it is unprovoked (present without stimulation). Some patients have pain just in the outer vulva, while others also present with pelvic floor muscle tension or urethra, bladder, or vaginal canal irritation.

The definition of vulvodynia itself states there is no known reason. This means it is not because of a skin disruption, hormonal disorder, herpes or other skin conditions, or active infection, such as yeast. This means we really don’t know just why a person has symptoms once they have been medically ruled out.

When we look at the symptoms of neuralgia (an irritated or overly talkative nerve), we find symptoms listed such as pain, hypersensitivity, burning, tingling, itching, or trigger points. Certainly, there is a lot of overlap between neuralgia symptoms and vulvodynia symptoms.

Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation Part 1 and Boundaries, Self-Care and Meditation Part 2, scheduled for November 23, are instructed by Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC and Jenna Ross, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC.

Women are often socialized to be these kinds of words: sweet, likable, giving, generous, helpful, and accommodating. If that bend of conditioning is particularly strong, it shapes our relationships and our career choices. We often choose a career that makes us feel like we are being sweet, helpful, and generous. These traits serve others around us well, and they may increase our likability with others. We begin to see our likability as how much we embody these traits, and we can see our worth to others and ourselves as how much we show up in this one-dimensional way to others.

Taken to an extreme, this starts to look like being uber-available for patients calling them on our own time, emailing from home, running over in sessions to give the patient everything they could possibly get from a session, adding in hours to accommodate a patient, writing our notes during our lunchtime, and finding that resource for our patient by searching the web for an hour.

So often as “pelvic floor therapists”, our name and scope of manual treatment can seem to center around stretching or strengthening pelvic floor muscles. But, if you have been practicing for a while, maybe you want to go deeper.

We talk in the Pelvic Function Series about “zooming out” (considering postural, musculoskeletal, breathing, autonomics, and pressure systems). We also have noticed in our field an increased emphasis on the nervous system for regulating the system.

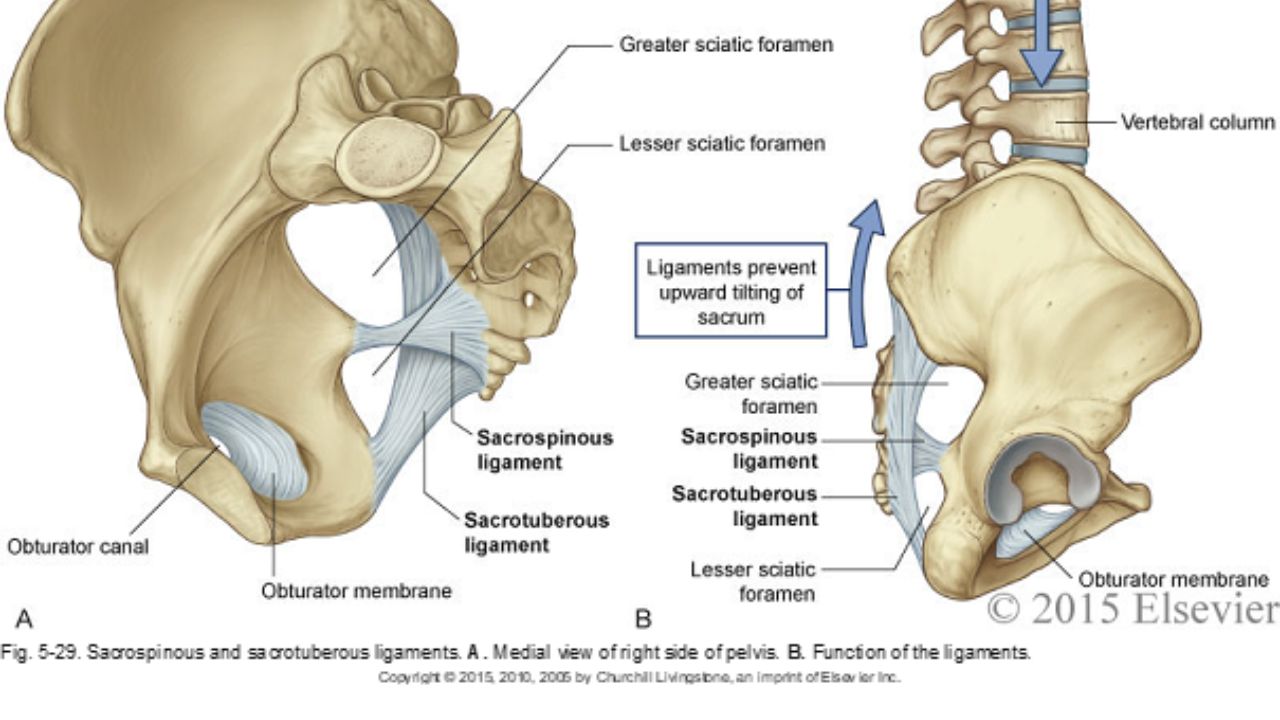

We also talk about “zooming in”, bringing our focus inside the pelvis. That could be pelvic floor muscles, but if we want to zoom in even deeper, we may start to look at peripheral nerves, supportive ligaments, and the interplay between bones, ligaments, fascia, and muscles that could be keeping pain, dysfunction, over-activity, or tension syndromes alive.

Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC has written the following courses: Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment/Treatment, as well as Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment/Treatment. She has co-authored the Pelvic Function Series Capstone course and the Boundaries, Self Care, and Meditation Course. Nari’s passions include teaching students how to use their hands more receptively and precisely for advanced manual therapy skills while keeping it simple enough to feel successful. She also is an advocate for therapists learning how to feel well and thrive as they care for others, which is a skill that can be developed.

If you've taken the Pelvic Function Series Capstone or Pelvic Function Level 2B and you've gotten curious about nerves, you've likely started to think about what is nerve pain and what is muscle restriction. In those classes, we discuss several lumbar nerves and how the restrictions could be creating pain in the anterior vulva, anterior hip, lower abdomen, groin, or inner thigh. Or perhaps you've started to notice certain patients have pain along nerve distributions we talk about in either of those courses. Sometimes we have patients who have had surgeries like c-sections, inguinal hernia repairs, or hysterectomy, and we notice they are having a persistent pain or weakness problem that isn't easily explained through muscle alone. I like to think of the nerve as the program for the robot, and the muscle as the way the robot moves. Nerves are a way to get deeper to the root of what may be happening.

The female sexual response cycle is more than physical stimulation. As pelvic therapists, we frequently find ourselves treating pelvic pain that has interrupted a woman’s ability to enjoy her sexuality and sensuality. As physical therapists, we focus on the physical limitations and pain generators as a way of helping patients overcome their functional limitations. However, many of us find that once many of the physical symptoms have cleared with pelvic floor and fascial stretching, our patients are still apprehensive to engage physically, or they are not able to derive pleasure. There is clearly a gap that needs to be bridged that goes beyond pain.

Last year I taught my class, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment. I was honored and astounded to have Dee Hartmann, PT in my class. For those of you who do not know Dee, she has been a champion of our field for a long time, and she has been instrumental in elevating physical therapy as a first line of treatment in pelvic pain through her work, international leadership, and representation in multiple organizations, including APTA SOWH, ISSVD, IPPS, NVA, ISSWSH, and as an editor for the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

In this manual nerve class, I was teaching how to treat the path of the genitofemoral nerve, which affects the peri-clitoral tissues and sensation. We also covered manual therapy approaches to decrease restriction in the clitoral complex and improve the blood flow response in this region. Dee was fascinated and looped me into what she had been working on for the past several years. She has been working as part of a company called Vulvalove with her partner, sex therapist, Elizabeth Wood on studying and teaching women how to recapture their sensuality. Immediately, we wanted to combine forces in some way to present a way to approach these issues. So, when Dee invited me to present with Elizabeth and her at the Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association (CSM) this year, I was humbled and excited to jump on board.

Birthing can be an unpredictable process for mothers and babies. With cases of fetal distress, the baby can require rapid delivery. Alternatively, in cases with cephalo-pelvic disproportion, the baby has a larger head, or the mother has a decreased capacity within the pelvis to allow the fetus to travel through the birthing canal. Additionally, the baby may have posterior presentation, colloquially known as “sunny side up” in which the baby’s occipital bone is toward the sacrum. With any of these situations, it is good to know c-sections are an option to safely deliver the child.

Women may also be inclined to try to get a c-section to avoid pelvic complication or tears or because of a history of a severe prior tear. As pelvic therapists, we know that the number of vaginal births and history of vaginal tears increase the risk of urinary incontinence and prolapse. Yet, many therapists are unfamiliar with the effects of c-section and the impact of rehab for diastasis.

A 2008 dissection study of 37 cadavers studied the path of the ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves. The course of the nerves was compared with standard abdominal surgical incisions, including appendectomy, inguinal, pfannestiel incisions (the latter used in cesarean sections). The study concluded that surgical incisions performed below the level of the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS) carry the risk of injury to the ilioinguinal and iloiohypogastric nerves 1. Another 2005 study reported low transverse fascial incision risk injury to the ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves, and the pain of entrapment of these nerves may benefit from neurectomy in recalcitrant cases.2

Most people are told that inguinal hernia repair is a low risk surgery. While death or severe injury is rare, penile or testes pain after hernia repair is not a novel or recent finding. In 1943, Magee first discussed patients having genitofemoral neuralgia after appendix surgery. By 1945, both Magee and Lyons stated that surgical neurolysis gave relief of genital pain following surgical injury (neurolysis is a surgical cutting of the nerve to stop all function). However, it should be noted that with neurolysis, sensory loss will also occur, which is an undesired symptom for sexual function and pleasure. In 1978 Sunderland stated genitofemoral neuralgia was a well-documented chronic condition after inguinal hernia repair.

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

In 1999 Stark et al noted pain reports as high as 63% post hernia repair. The highest rates of genitofemoral neuralgia are reported with laparoscopic or open hernia repair (Pencina, 2001). The mechanism for GF neural entrapment is entrapment within scar or fibrous adhesions and parasthesia along the genitofemoral nerve (Harms 1984, Starling and Harms 1989, Murovic 2005, and Ducic 2008). It is well known that scar and adhesion densify and visceral adhesions increase for years after surgery. Thus, symptoms can increase long after the surgery or may take years to develop. In 2006, Brara postulated that mesh in the region can contribute to subsequent genitofemoral nerve tethering which can be exacerbated by mesh in the inguinal or the retroperitoneal space. With an anterior mesh placement, there is no fascial protection left for the genitofemoral nerve.

This post is part two of Nari Clemon's series on practitioner burnout, compassion fatigue, and the story of a pelvic rehab therapist who struggled to care for herself while caring for patients. Read part one here.

There is a point where caring so much and wanting to help becomes counter-productive to us, until we burn out. We can develop true compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue makes us feel apathetic, spent, and sometimes even jaded or cranky. But, how do we turn that caring off in time? Our compassion is what led us to this field in the first place.

That day, I talked to my colleague and close friend, whom I was teaching with, Jen VandeVegte. Jen and I both felt that conversation was a wake-up call. We talked about seeing this same scenario at our courses: so many amazing therapists getting spent, and our best therapists getting burnt out. People were coming back with enhanced skills course after course, but many of them were looking weary and tired...

Last year, I was teaching our Pelvic Floor Series Capstone course. It was the end of day three of the course. Most, students were thanking us for a course that filled in so many gaps in their practice and taught them a whole new way to use their hands. They were feeling energized and excited to bring all the new information back to their patients who had plateaued, so this was a surprising and atypical comment. To those of you who are unfamiliar with Capstone, it is a course for experienced pelvic therapist who have already taken three of the series courses, and it was written to address truly challenging patients, to learn to problem solve with manual therapies, to address all the things that my co-authors and I wished we had known five years into our field. It teaches complex problem solving and more receptive and dynamic use of their hands. So, usually, by this course, therapists are fully committed to this field and geeked-out to get so many more pearls. They are usually on board and looking for more sophisticated tools.

As one student, Soniya (name changed) was walking out, she said, “I took this course to figure out if I want to treat pelvic patients, and I definitely don’t. It confirmed what I already knew about pelvic rehab being wrong for me.” I was so confused at that point. All I could say in that moment was, “Can you please tell me more about that? I’m interested.”

Soniya went on to explain that she used to be a pelvic therapist. She said she loved it at first. But, she got so enmeshed with her patients and found she stopped having energy for the rest of her life: her kids, her health, her own enjoyment. She said she would go into her “dark cave” treatment room with her patients, isolated with them one at a time, and come out spent and depleted at the end of the day. She clarified that it was rewarding helping people so profoundly, but there came a point when she had to choose between helping others and saving herself. She changed back to outpatient ortho, choosing to treat in the gym, dynamically interacting with other PT’s all day and not being one-on-one in a room with patients and her problems. She also changed to part time, stating she just couldn’t be around patients five days a week anymore.

Recently, I had a patient present to my practice with unretractable vaginal pain that was causing her quite a bit of suffering. Peyton (name changed) had been referred by a local osteopathic physician. For around a year, she had increasing severe vaginal pain. There was no history of assault, trauma, fall, or injury around the time of onset of symptoms. However, she had a kidney infection that caused back pain in the month prior to her pain onset.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

Objective findings revealed normal range of motion in her spine with the exception of limited forward flexion (feeling of back tightness at end range). Hip screening was negative for FABERS, labral screening or capsular pain patterns. General dural tension screening was positive for increased lower extremity and sensation of back tightness with slump c sit. Neural tension test was positive bilaterally for sciatic, R genitofemoral, L Iliohypogastric and Ilioinguinal nerves, and bilateral femoral nerves. Patient had a mild, barely perceptible lumbar scoliosis, and development of bilateral lower extremities and feet was symmetric and normal.