Did you know that chronic pain affects an estimated 51.6 million adults in the United States alone? That's almost 21% of the population (1). It's a debilitating condition that can disrupt daily life and limit one's ability to function. But what about those with hypermobility? Often individuals with hypermobility are even more susceptible to chronic pain and their treatment may require a unique approach.

There are many variables that make a person more susceptible to developing chronic pain. Some of these include genetics, prior trauma, culture, and health history. Patients with hypermobility are more likely to develop chronic pain and may also need to be treated with a different lens than the rest of the population.

What is Hypermobility

Hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) includes joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS) as one of its conditions and is a connective tissue disorder characterized by chronic musculoskeletal pain due to joint hyperextensibility and is a common cause of chronic pain, fatigue, headaches, anxiety, orthostasis, and abdominal pain. Hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) is sometimes considered a milder variant of hypermobile EDS (hEDS) and is seen in up to 3% of the general population, with a prevalence rivaling fibromyalgia, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis (2).

Joint hypermobility implies a range of motion of a joint that exceeds the documented “norm.” Norms for each joint are determined by the specific joint anatomy, the person’s age, sex, and ethnicity. Hypermobility is typically scored using the Beighton scale requiring at least a 5 to be classified as systemically hypermobile. The Beighton score is determined by 9 points awarded for each described condition met. The conditions include (3,4):

- Elbow hyperextension of at least 10 degrees (one for each elbow)

- Knee hyperextension of at least 10 degrees (one for each knee)

- Ability to passively extend the pinky finger to 90 degrees or more (one for each hand)

- Ability to touch the thumb to the forearm with wrist flexion (one for each hand)

- Ability to forward flex the trunk at the hips and place both palms on the floor with knees extended.

Hypermobility as a problematic condition occurs on a spectrum and ranges from Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (HSD) to genetic connective tissue disorders such as hypermobile EDS (hEDS). Patients with connective tissue disorders often have other symptoms associated with the syndrome such as fragile blood vessels or cardiac arrhythmias (3). Those with generalized joint hypermobility are less likely to have other associated comorbidities.

Hypermobility and Rehab

A patient with hypermobility must have their hypermobility considered in their treatment plan as their tissues, and force tolerance of tissues, differ from the rest of the population. Patients with hypermobility may present with decreased strength overall and require more strength than typical to perform activities. This is likely due to the extensibility of the tendons and ligaments, changing the force a muscle can produce. Patients with hypermobility also often have decreased proprioception, as their tissue laxity cannot provide as much awareness to the brain. These variables can lead to a higher incidence of injury, with dislocation common for those with hEDS (4).

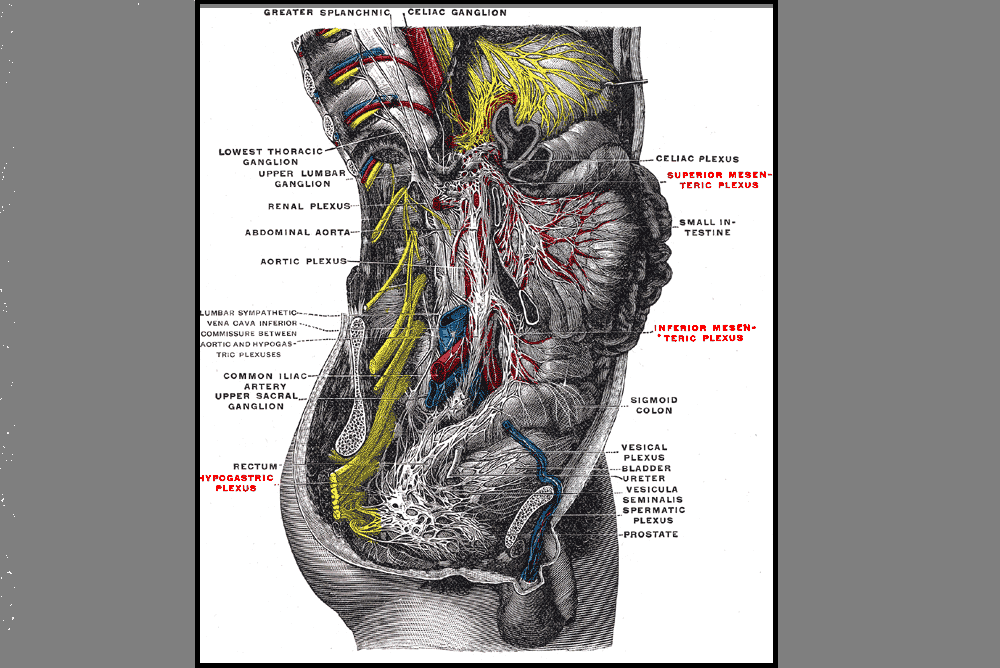

Hypermobility is also correlated with pelvic pain and dysfunction, especially in female patients. They are more prone to pelvic organ prolapse but also may present with pelvic floor muscle overactivity (3) creating a difficult case to treat, especially if they have chronic pain in addition. This patient will often benefit from rehabilitation to address the prolapse, muscle overactivity, and then coordination of core and pelvic stabilizers. Knowing that the patient has hypermobility can be vital to the successful treatment plan for this presentation. When treating patients with hypermobility, they often have decreased functional tolerances for loading, not only at the joints but also systemically. hEDS especially, is highly associated with autonomic dysfunction such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which may affect your treatment plan as well. A portable pulse oximeter and slow positional changes may be helpful in decreasing and monitoring symptoms (3,4).

Pain Patterns and Hypermobility (3)

Pain Patterns and Hypermobility (3)

Pain patterns for the hypermobile patient include all 3 subtypes of pain.

- Nociceptive Acute Pain

- Neuropathic Pain

- Nociplastic Pain

Nociceptive acute pain will occur at localized injury sites with frequent dislocations, strains, and sprains. These recurrent injuries can then lead to chronic musculoskeletal changes of the joint that affect function and gait.

Neuropathic pain can also become problematic for this population. Due to the increased laxity of their vertebrae, they may suffer from higher incidences of spinal cord compression and peripheral nerve compression. It is also becoming more common to evaluate this population with a dermal biopsy for small fiber neuropathy. As the patient experiences continued nociceptive and neuropathic pain inputs over and over, their nervous system may also sensitize causing both peripheral and central sensitization with nociplastic pain.

Nociplastic pain may then transform into widespread generalized pain. As their pain patterns progress, they may start to experience more fear avoidance behaviors and may become deconditioned. Deconditioning in turn can lead to more injuries and continues a recurrent cycle for these patients.

Conclusion

Knowing that patients with hypermobility are more susceptible to chronic pain allows us to treat this population more effectively. As rehab practitioners, we can educate the patient, improve strength, improve stability, improve proprioception, and work to desensitize the nervous system. A sensitive nervous system may be the initial hurdle with the hypermobile patient.

Pain neuroscience education is the first step to educate the patient on how their nervous system functions and to decrease fear they may have around pain. After education, there are several physical interventions we can use for the nervous system including dry needling, spinal mobilization, manual therapy, and exercise.

Ready to Learn More?

Expand your knowledge, experience, and treatment in understanding and applying pain science to the chronic pelvic pain population with Alyson Lowrey and Tara Sullivan in their upcoming course Pain Science for the Chronic Pelvic Pain Population on August 17-18, 2024.

This course is not specific to the patient who is hypermobile. However, there are portions of the course that address this population. This course provides a thorough introduction to pain science concepts including classifications of pain mechanisms, peripheral pain generators, peripheral sensitization, and central sensitization in listed chronic pelvic pain conditions; as well as treatment strategies including therapeutic pain neuroscience education, therapeutic alliance, and the current rehab interventions' influence on central sensitization.

Pain Science for the Chronic Pelvic Pain Population is a remote course that will provide you with the understanding and tools needed to identify and treat patients with chronic pelvic pain from a pain science perspective. Lecture topics include the history of pain, pain physiology, central and peripheral sensitization, sensitization in chronic pelvic pain conditions, therapeutic alliance, pain science and trauma-informed care, therapeutic pain neuroscience education, the influence of rehab interventions on the CNS, and specific case examples for sensitization in CPP.

References:

- Rikard, S. Michaela, et al. “Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2019–2021.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, vol. 72, no. 15, 14 Apr. 2023, pp. 379–385, DOI: https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1.

- Kumar, Bharat, and Petar Lenert. “Joint hypermobility syndrome: Recognizing a commonly overlooked cause of chronic pain.” The American Journal of Medicine, vol. 130, no. 6, June 2017, pp. 640–647, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.02.013.

- Syx D, De Wandele I, Rombaut L, Malfait F. Hypermobility, the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and chronic pain. PubMed. 2017;35 Suppl 107(5):116-122.

- Scheper M, De Vries JE, Verbunt J, Engelbert RHH. Chronic pain in hypermobility syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hypermobility type): it is a challenge. Journal of Pain Research. August 1, 2015:591-601

AUTHOR BIO

Alyson Lowrey, PT, DPT, OCS

Dr. Lowrey attended the University of New Mexico where she received a BA degree in Psychology in 2011. She then attended the University of New Mexico School of Medicine to earn her Doctor of Physical Therapy degree in 2014. Following graduation from UNM, Alyson completed the HonorHealth Orthopaedic Residency program in 2015 and became a board-certified orthopedic specialist (OCS) in 2016. She is now the director of that residency program and lectures about pain and pelvic dysfunction in the curriculum. Alyson treats the pelvic floor patient population through an orthopedic approach, working closely with pelvic floor specialists. This allows for a wholistic style addressing the entire patient from a functional perspective. Alyson’s clinical interests include the evaluation and treatment of chronic pain, lumbar and cervical spine disorders, foot and ankle disorders, pelvic pain, and clinical instruction. She is certified in dry needling and an APTA-certified clinical instructor, regularly taking students from several PT schools. She participates in Creighton’s and Midwestern University’s Doctor of Physical Therapy programs as adjunct faculty assisting in lab and lecturing in Biomechanics, Kinesiology, and Musculoskeletal courses. Outside of the clinic, she enjoys being active, doing yoga, crafting, and spending time with her husband and cats.