I will never forget when my sister, my bestie, told me she wanted to end her life. We were on the phone late one night, tears flowing. Depression was always a companion, but I had never heard her in such a state of despair. We made a plan that she would call the suicide hotline, then call her therapist and her doctor in the morning for urgent care. She made it through the night. Later, I went to her therapist with her so I could better understand and support my sister. She did her due diligence, adjusting medication and staying open and honest in therapy. Suicidal ideations would sometimes flare when there were triggers, but she was able to work through them, and now they are in the past.

Contrast that story with another. Ryan was a sweet woman who developed pudendal neuralgia after a routine hysterectomy. Right away, she told me she had a counselor who she loved who helped her navigate life with DID (Dissociative Identity Disorder) and that I’d probably be interacting with various personalities during our sessions. She helped me understand how to best support her during her care. We worked well together, and although she struggled with both the pain and the unfairness of what happened to her, she was well supported. Then her sweet dog passed away. It was so hard for her. She kept going through pain and heartache and found another pooch to adopt. And then the next visit, she didn’t show. And the next, and the next. And then I found out she was gone. Suicide. This hit me hard. Were there signs that I missed? Was there anything I could have done?

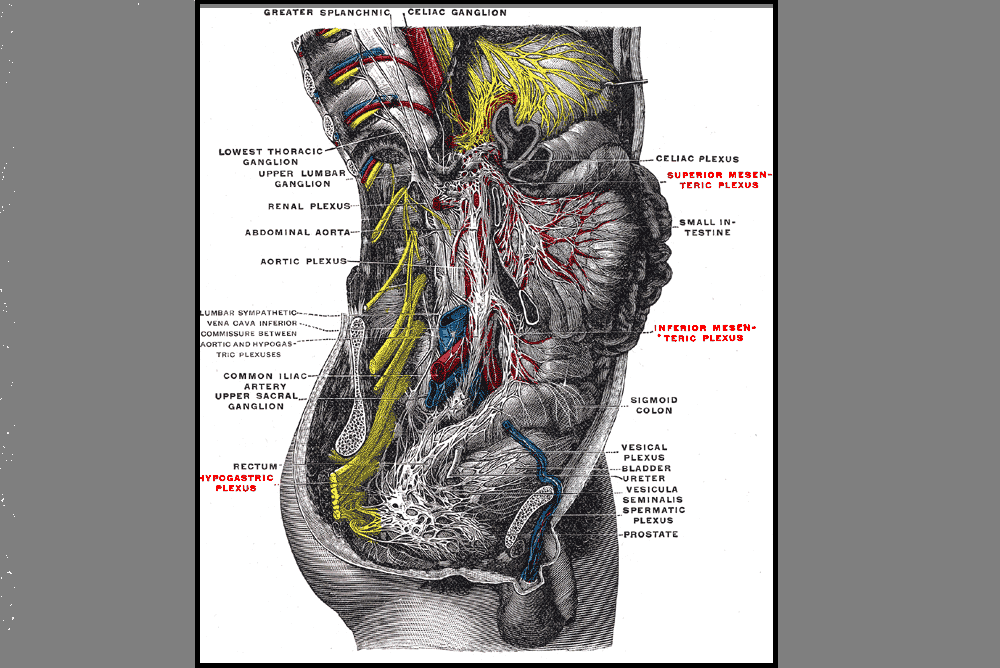

As pelvic rehab providers, we sometimes see people who have intense physical pain often combined with significant emotional wounds. In a study of 713 women seeking support for pelvic pain, 46.8 reported having sexual or physical abuse history, and 31.3 were positive for PTSD (1).

Chronic pelvic pain impacts all aspects of people’s lives: physical, financial, relational, emotional, and mental. People can also become dependent on narcotics or recreational drugs which may lead to intentional or accidental overdose, per Philip Hall, a gynecologist in Australia (2).

In a study of 13,500 women with endometriosis, half reported experiencing suicidal thoughts (3).

So what’s our role as health care providers?

It’s important to note that not everyone who is considering suicide will admit it, and not everyone who thinks about suicide will follow through with it. However, all threats of suicide should be taken seriously. Let people know you care, they are not alone, and help is available.

Ask questions: It may feel scary, but it won’t push someone into harmful action. The Columbus Protocol, listed below, uses three questions to identify suicide risk. If someone answers yes to any question, they have a significantly higher risk of suicide and need support(4).

- Have you wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up?

- Have you had any thoughts about killing yourself?

- Have you thought about how you might do this?

Be observant of warning signs:

- people may talk about taking their own life, wishing they could end things, wishing they were never born

- you may observe extreme mood swings

- the person may start putting their affairs in order

- there may have been a recent trauma or crisis

- you may notice withdrawal or sudden calmness

- the person may participate in risky or reckless behavior

If someone admits to planning for suicide, as health care providers, we MUST take supportive action. If your facility does not have a protocol, consider these steps:

- Call 911 and perhaps a friend or family member to meet the person at the hospital

- Stay with the person until help arrives

- Remove any objects that may be used for harm

- Listen with kindness and understanding

- Stay Connected: studies show that follow up after an event decreases the risk of suicide death(5)

It’s helpful also to note the following protective behaviors, as reported by psychiatry.org(6):

- Connection with health care providers

- Strong connections between family, friends, community

- Skillfulness around problem-solving and conflict resolution

Knowing what to look for, what questions to ask, and how to get someone the help they need empowers health care providers to provide the best support for patients struggling with suicidal ideation and contemplation.

There are local and national resources for us as well.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-(TALK) (1-800-273-8255). The Lifeline provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources for you or your loved ones, and best practices for professionals in the United States(7).

References:

- Meltzer-Brody, S., Leserman, J., Zolnoun, D., Steege, J., Green, E., & Teich, A. (2007). Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 109 (4), 902-908.

- https://standrewshospital.com.au/about-us/news/news-listing/2016/09/05/chronic-pelvic-pain-linked-to-suicides-in-young-women

- https://www.bbc.com/news/health-49897873

- https://cssrs.columbia.edu/the-columbia-scale-c-ssrs/about-the-scale/

- Motto, J. A., & Bostrom, A. G. (2001). A randomized controlled trial of postcrisis suicide prevention. Psychiatric Services52(6), 828-833.

- https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/suicide-prevention

- https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/