Trauma. The word holds so many meanings. Say the word and depending on your perspective - it could mean Trauma (like trauma center which is physical injury focused) or trauma (like unwanted experience causing adverse socioemotional consequences). In medical environments, the former would be qualified as ‘Big T’ Trauma, and the latter would be ‘little t’ trauma. Once you are immersed in the ‘little t’ trauma field, the Big and little traumas change meanings. The Big T Trauma would describe a significant event, whereas the little t trauma would include multiple, smaller microaggressions accumulating into adverse effects.

I have worked in trauma since 1996. And the changes have been vast. Thankfully, long gone are the days that I am educating physicians in the ER on how to complete a rape kit and how to perform care that is patient-focused and empowering. I would like to think that advocates are no longer having to explain to medical providers that RU22 is not an ‘abortion pill’ but a medicine that is required to be offered BY LAW in Illinois (SASETA) to reduce the risk of implantation after a rape. I started working in ERs advocating for the medical and legal rights of sexual assault survivors BEFORE Law-and-Order SVU brought these patients into mainstream culture in 1999. Thank you, Olivia and Elliot for bringing this awareness into our living rooms.

When I was a mental health counselor in the 90s and 2000s, it was quite remarkable that trauma was not included in mental health services. PTSD definitions were changing frequently within the DSM (Diagnostic Statistical Manual) during this time. Definitions and inclusion of trauma within mental health continue to change frequently to this day. In the 90s, I was working with youth in lower socioeconomic populations and their trauma was both palpable and unseen. Also, during this time, education and awareness of developmentally appropriate sexual health were not a thing! I remember my supervisor calling me and asking me what to do with a teenage female who was masturbating with a brush. And I was like OK - which side of the brush… is she masturbating for pleasure which is normal/appropriate or is she hurting herself and we need to screen her for sexual abuse? I screened her for abuse (my supervisor was not comfortable- she ended up disclosing her own abuse) and the teenager did not disclose abuse or self-harming behaviors, so it was normal sexual behavior. I could go on about cultural and gender taboos, but that is literally power for the course.

When I made the change from mental health to physical therapy in the mid-late 2000s it soon became apparent that trauma was not considered within rehabilitation. In 2011, I created the first in-service on trauma - focusing on education, awareness, and teaching Polyvagal theory. Stephen Porges introduced Polyvagal much earlier in 1994 and I am looking forward to the day he receives the Nobel Prize for his work, as he should. I am ecstatic that Polyvagal is no longer an obscure construct. I see many friends and fellow clinicians normalizing the terms neuroception and interoception, and I am elated. This is quite different from when ten ten-plus years ago, the response to my course was a not-so-friendly ‘Stay in your lane, PT’ (and this is not addressing the fact that our fellow OT and SLP comrades are doing this challenging work). I am so glad that is not the case anymore. Trauma-informed care (TIC) is becoming the norm, not the exception. And I am so happy to see what other rehabilitation specialists are doing within the field! There is so much space for us all.

Here is an outline of what we expand upon within the course Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist:

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is a universal approach within healthcare that recognizes and responds to the impact of traumatic experiences on individuals. It aims to create a supportive environment that promotes healing and recovery while minimizing the risk of re-traumatization. The core principles of trauma-informed care include understanding the prevalence and effects of trauma, recognizing the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients and staff, and integrating knowledge about trauma into practices, policies, and procedures. In order to understand the effects of trauma, an understanding of neurobiology of the brain and function of the autonomic nervous system are foundational.

Key Principles of Trauma-Informed Care:

Safety:

Ensuring physical and emotional safety for the CLINICIAN, clients, and staff. This involves creating an environment where individuals feel secure and respected.

Trustworthiness and Transparency:

Building trust through clear, consistent, and transparent practices. Ensuring that decision-making processes are transparent, and that information is shared openly.

Peer Support:

Encouraging and incorporating peer support and mutual self-help as essential components of trauma-informed care. Peer support helps to build trust, enhance collaboration, and promote recovery.

Collaboration and Mutuality:

Emphasizing partnership and the leveling of power differences between staff and clients. Everyone involved in the care process collaborates and shares in the decision-making.

Empowerment, Voice, and Choice:

Prioritizing the empowerment of individuals and recognizing their strengths. Offering choices and supporting individuals in their decisions helps to foster autonomy and resilience.

Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues:

Being responsive to cultural, historical, and gender contexts. This involves recognizing and addressing the impact of systemic oppression and discrimination and promoting cultural competence among staff.

Implementation Strategies

Training and Education:

Providing ongoing training for EVERYONE on the principles of trauma-informed care and the impact of trauma. This includes recognizing trauma responses and learning how to create a supportive environment.

Policy and Procedure Review:

Introducing TIC and revising organizational policies and procedures to ensure they reflect trauma-informed principles. This includes practices related to intake, assessment, treatment planning, and discharge.

Environment Modification:

Creating physical spaces that promote a sense of safety and calm. This can involve changes to the layout, lighting, noise levels, and decor.

Client/Patient Involvement:

Involving clients in the planning and evaluation of services to ensure their perspectives and needs are considered.

Support Systems:

Providing support for EVERYONE to prevent burnout and secondary traumatic stress. This can include supervision, debriefing sessions, and access to mental health resources.

Trauma is personal and individualized. There is no one size fits all or one technique can be used for all.

Benefits of Trauma-Informed Care:

Improved Outcomes:

Trauma-informed care can lead to better engagement, adherence to treatment, and overall outcomes for clients/patients.

Reduced Re-traumatization:

By creating a supportive and understanding environment, the risk of re-traumatizing individuals (read: ALL of us) is minimized.

Enhanced Trust:

Building trust between clients/patients and providers fosters better communication and a stronger therapeutic relationship.

Empowerment and Recovery:

Empowering individuals to take an active role in their care promotes recovery and resilience.

Remember, trauma-informed care is a comprehensive approach that involves understanding, recognizing, and responding to the effects of trauma. By integrating trauma-informed principles into practice as UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS, we can create safer, more supportive environments that promote healing and recovery for ourselves and all individuals.

It has been an honor to bring this course, Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist, into the rehabilitation space. In the last 10 years, and especially since COVID-19, it is beautiful to see how TIC has become mainstream. One word of caution: We need to watch out for end-of-spectrum gas lighting. We all have seen patients whose symptoms and experiences have been minimized when their trauma has not been taken into consideration. This can also happen at the other end of the spectrum. I had a patient who sought out gynecological treatment from a ‘trauma-focused gynecologist.’ This patient we all know - chronic pelvic pain with a history of endo, PCOS, IBS-M, and IC. When she went to this clinician, she was told that her pain was caused by trauma, whether she remembered the trauma or not. The patient is a counselor and has been doing much work with her mental health team. She was open to ‘unknown trauma’ but we both thought she should seek another provider. Two weeks later, she had surgery for appendicitis.

TIC allows us to refocus on our work within rehabilitation and is open and supportive towards all people. This work is AMAZING. This work is HARD. This work is quite frankly one of the reasons we were placed on this earth. To be present for another person’s pain, whatever type of pain that is - is one of the most special care one can give to another.

Please be so proud of all the work you have done. Know that you are enough. And that you can be present for others. I hope you find even more support and knowledge with any trauma course that you choose to take, I just hope to meet you in mine on September 21-22!

AUTHOR BIO:

Lauren Mansell DPT, CLT, PRPC

Lauren received her Doctor of Physical Therapy degree from Governors State University and a Bachelor's Degree in Psychology and Sociology from Northwestern University. Before becoming a physical therapist, Lauren counseled suicidal and homicidal SES at-risk youth who had survived sexual violence. Lauren was certified as a medical and legal advocate for sexual assault survivors in 1999 and has advocated for over 130 sexual assault survivors of all ages in the ED. Lauren's physical therapy specialty certifications include Certified Lymphedema Therapist (CLT), Pelvic Rehabilitation Professional Certificate (PRPC), and Certified Yoga Therapist (CYT). She is a board member of the Chicagoland Pelvic Floor Research Consortium, American Physical Therapy Association Section of Women's Health and Section of Oncology.

Lauren received her Doctor of Physical Therapy degree from Governors State University and a Bachelor's Degree in Psychology and Sociology from Northwestern University. Before becoming a physical therapist, Lauren counseled suicidal and homicidal SES at-risk youth who had survived sexual violence. Lauren was certified as a medical and legal advocate for sexual assault survivors in 1999 and has advocated for over 130 sexual assault survivors of all ages in the ED. Lauren's physical therapy specialty certifications include Certified Lymphedema Therapist (CLT), Pelvic Rehabilitation Professional Certificate (PRPC), and Certified Yoga Therapist (CYT). She is a board member of the Chicagoland Pelvic Floor Research Consortium, American Physical Therapy Association Section of Women's Health and Section of Oncology.

As adjunct faculty, Lauren teaches Special Topics: Pelvic Rehabilitation Physical Therapy at Governors State University. Lauren works at the University of Chicago providing pelvic rehabilitation, lymphedema, and oncological physical therapy within Therapy Services and the Center of Supportive Oncology. She treats pelvic pain, urinary incontinence, bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, lymphedema, lymph node transfer/bypass, stem cell transplant, and bowel/bladder/sexual/functional concerns of patients undergoing HIPEC (hyperthermal intraperitoneal chemotherapy). Lauren is a 2017 Fellow of the Chicago Trauma Collective. As a trauma-sensitive practitioner, her goal is to empower patients to create meaningful, healthful lifestyle changes to improve their physiology and wellness

Congratulations to Dr. Mia Fine (they/she) for achieving their Ph.D. in Clinical Sexology and on their book titled 'From Unwanted Pain to Sexual Pleasure: Clinical Strategies for Inclusive Care for Patients with Pelvic Floor Pain' for their dissertation doctoral project.

Dr. Fine was gracious enough to share a draft of their dissertation with Herman & Wallace and to answer a couple of questions about how this impacts their practice and what they hope other practitioners will take away from their book and course Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists.

Mia's course is for the pelvic rehab therapist and others in the medical profession who work with patients experiencing pelvic pain, pelvic floor hypertonicity, and other pelvic floor concerns and would like to learn applicable skills from the sex therapist's clinical toolkit. The next course date for Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists is August 13-14,

How does Trauma-Informed Care apply to the skills that you teach in your Sexual Interviewing course?

When I utilize the term ‘trauma-informed’ I am referring to therapeutic work that communicates expectations clearly (including prioritizing people’s access needs with this communication), invites clients awareness of their own agency, and is upfront about my scope of practice and my therapeutic approach, offers mutuality in inviting of questions and ongoing conversation about our work together, awareness that an individual can end therapy at any time, and share information at any time in our therapeutic space.

The modalities I utilize when working with clients who have experienced trauma include Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), Polyvagal Theory, Somatics, and Developmental Theory. While I integrate various theories and modalities into my work with clients, the methods above are empirical in their data to support healing from trauma wounds.

Trauma-informed means humility regarding cultural, racial, gender, sexual, and other minority experiences. I will not know all of the things but I will do my best to self-educate and not leave that responsibility to my clients. When I make a mistake I will appropriately, directly, and compassionately apologize for the harm I caused and invite opportunity for repair should the client be interested. Trauma-informed means collaboration in exploring therapy together, co-creating a space that feels safer to the client and checking in with them when I notice non-verbal cues that indicate activation, honoring a client’s pacing, and bringing awareness to the reality that as a therapist I hold power and while I don’t know a person’s full story there is always the potential for me to unintentionally activate a client so to share this possibility with clients and continuously check in about how our therapy is working for them. I keep my client’s well-being at the forefront of our work and I center their needs at all times while maintaining boundaries that keep everyone as safe and secure as possible.

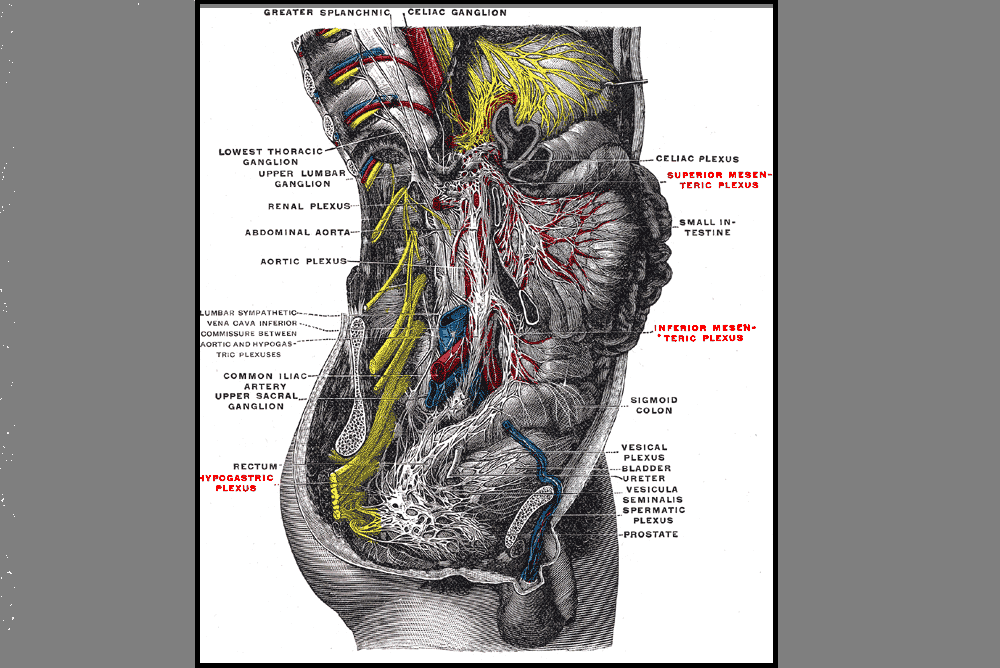

It is up to us as trauma-informed and inclusive providers to explore a person’s experience of pain by asking questions about onset, process, location, and impact, in addition to offering psychoeducation about anatomy, physiology (arousal, interest, desire), and self-regulation. This must be done alongside commitment to our patient’s co-regulation, normalization, and informed consent concerning the therapeutic process—all of which are needed for comprehensive trauma-informed care.

Can you explain how expanding what 'normal' is to practitioners can impact the patients and clients that they work with?

Sex is not supposed to be painful. How many people have come to me having had painful sexual intercourse for years and reported “pushing through”? The first time having intercourse does not necessarily have to be painful, but when our cultural narratives tell us “the first time having sex is painful for everyone” we end up ignoring the signals our bodies are offering because we have convinced ourselves that the pain is both okay and normal. The “pushing through” is a reflection of misogyny: people assume the first experiences people have with penetration are supposed to be painful. How is this misogynistic? Well, who benefits from a person “pushing through” pain? The partner with the penis. Important to note here as well is that enthusiastic consent is ableist and ignores the mind-body connection because it does not take into account masking or fawning which are common experiences for many.

A quarter of people who experience sexual health concerns share this with their providers. Why such a small fraction? Fear. Fear of embarrassment and shame. Fear that there is something “abnormal” about them that mutates into the shame humans tend to experience in response. Fear that the concern won’t be held or taken seriously by their provider. Fear that, if it is addressed, will be at such a high financial cost that the treatment will be unaffordable. Fear that there’s not enough time or that they won’t be taken seriously. Fear of exclusivity, feeling othered, or misunderstood by their provider. Fear of the unknown because the reality is that people are afraid of what we don’t understand.

One of the major cultural issues we have in the US is the perpetuation of sexual stigma which is largely associated with a lack of comprehensive sex education. People don’t have access to basic information about their own bodies which influences our beliefs about sex, pleasure, agency, communication, and self-awareness. Sex education should be a birthright, and yet we are so far behind the curve that it sometimes feels impossible to break down the barriers.

When I first started in this career it would often take clients months of working with me to feel comfortable enough to talk about where they felt pain during sex, but in developing the tools to co-create safety in our therapeutic relationship and the skills to ask the important questions with compassion and patience, I learned how to better hold space for healing.

Patients don’t often know what information is important for them to share with us (which is why offering visuals of where the pain is located is important). How could they know what information is important to offer when mental and sexual health are so deeply stigmatized? The stress of shame and embarrassment that people feel about their bodies is emotional pain that further exacerbates the physical pain that they came to therapy to address in the first place. It’s a terrible and self-perpetuating cycle.

I teach people the difference between a vulva and a vagina one thousand times a year. If a client does not know the terminology for labia, vulva, vagina, and clitoris, how are they supposed to know when their sexual health is of concern? If a person enters sex therapy with “sexual pain” but is unable to distinguish the difference between their labia and vagina (that they are different body parts, where they are located, and what their functions are) we cannot expect them to accurately articulate the location of pain or comprehend potential solutions. “What is your hygiene process when cleaning your vulva?” may activate the fight or flight response in clients if they do not know what their vulva is or that there could be a good hygiene process, in addition to the shame of not knowing. How are they supposed to know where or to whom they may ask for help?

An online search for “anatomical vulva”, “pelvic floor pain”, “vaginismus treatment” and 99% of the images and figures you will see are those of hairless, slender bodies with white/light skin and small labia. Racism and white supremacy are present everywhere. The anatomical depictions of vulvas are of white bodies, the people modeling in vaginismus treatment advertisements are white, and the language is geared toward and written for white people. I was intentional about not featuring white vulvas in this book because white bodies should not be the default of what is mainstream. This lack of diversity in skin tone and variation of body type is another reflection of racism called “colorism”. White and light skin bodies are viewed as more ‘normal’ and when we continue to center white bodies in visuals “because that is what is available” we perpetuate white supremacy. One goal is to disrupt the idea and practice of whiteness as the default. This is what it means to practice anti-racism and attempt to divorce ourselves from white supremacy.

The impact of shame shows up in the pervasive erotophobia rampant in our society. Erotophobia can be broadly defined as a “fear of sex” or more specifically a “fear of intercourse”. When erotophobia is judgment as a result of societal shame and stigma, we can navigate it by deconstructing the etiology and impact of messages received; when it is a result of a mental health condition such as Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), we do deep trauma and/or anxiety/exposure work. Because of the vast impact of shame, people fear sharing sensitive information about themselves with others, including therapists who are trained to help them. Often, therapists are untrained in sexual health which also can contribute to erotophobia and shame. When therapists have not done their own work on sexuality, and remain untrained in these areas, they may be afraid to discuss sex with their clients which reinforces the belief that topics regarding sex are shameful.

When people do not have the language to articulate what is happening in their body, as significant as the pain or discomfort might be, talking about sex with a provider is often the last item on a long list of concerns they bring to a medical appointment. Symptoms of sexual pain may be hidden by other “more pressing” concerns such as anxiety, depression, PTSD, or sleep issues. While these are of course vital for a medical provider to know, having 20 minute appointments with a physician who will prioritize the “presenting concern” that they came in to seek treatment for leaves very little time to discuss unwanted sexual pain. After 15-20 minutes of a medical appointment (if it goes well), a patient might feel comfortable enough to bring up their sexual concern, but this might leave 1 minute for it to be acknowledged and no time to conduct a comprehensive assessment or develop an intentional plan. We call these last-minute oh-by-the-way’s “door-knobbing” for a reason. This is a call for medical clinics to have training in sexual health so they can create intake documentation that explores clients’ sexual health and ask the questions that are vital to gather necessary information ahead of time.

In the same way that people lack language and anatomic understanding, people also lack awareness of the mind-body relationship. Due to the ableist sex-negative culture in which we live, people are often not taught to have knowledge of or listen to our own body. We’re not taught that pain is a signal from the body telling us that something’s wrong.

Holly Tanner Short Interview Series - Episode 3 featuring Lauren Mansell

Lauren Mansell shares, "We're never ready to do this work. We're never ready to be perfect." Her course, Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist, is for all practitioners, not just physical therapists. Anyone licensed who works with patients can benefit from this topic. However, it can be offputting to put ourselves into a vulnerable position by registering for a course on this topic. Lauren understands this and comes prepared to teach other practitioners about trauma-informed care in the gentlest way possible.

Lauren Mansell, DPT, CLT, PRPC, CYT curated and instructs this course. Lauren worked in counseling and advocacy for sexual assault survivors before becoming a physical therapist. She also brings her experience as a 2017 Fellow of the Chicago Trauma Collective to teach trauma-informed care to medical providers. Trauma-informed care is especially important as the field of pelvic rehabilitation becomes more inclusive.

Pelvic rehabilitation and pelvic therapists really do treat the whole patient. Patients can present with pain, long-term issues, and undisclosed trauma that can be compounded when it includes sex, bladder, or bowel issues. Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist addresses several topics under this umbrella and spends time on each of the following:

- Explaining and describing compassion fatigue, trauma-informed care as well as anatomy, neurobiology, physiology of trauma, and the polyvagal autonomic nervous system

- Identifying risk factors and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

- Formulating techniques for reducing compassion fatigue, secondary trauma, and retraumatization

To learn more about trauma-informed care join H&W this weekend at Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist this September 25-26, 2021. The course will be offered again in 2022 if you are not available this weekend!

When looking through past blogs from The Pelvic Rehab Report, I ran across this gem submitted by Lauren Mansell explaining Trauma-Informed Approach and her course Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist. While it is not policy to recycle past articles, this was too good not to share again. Lauren succinctly explains the Trauma-Informed Approach that is instructed in her remote course, Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist, and it is as pertinent today as it was when first published in 2018.

[as written by Lauren Mansell]…

In my experience, trauma creates the trauma, and the body responds in characteristically uncharacteristic ways.

People in distress/trauma-affected do not respond rationally or characteristically, so I have learned to respond to distress/trauma in a rational, ethical, legal, and caring manner. Always. Every time. To the best of my ability, and without shame or blame.

Let’s talk briefly about Trauma-Informed Approach. This is a (person), program, institution, or system that:

- Realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery

- Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others affected

- Responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices

- Seeks to actively resist retraumatization

The tenets of Trauma-Informed Approach are:

- Safety

- Trustworthiness and transparency

- Peer support

- Collaboration and mutuality

- Empowerment, voice, and choice

- Cultural, historical, and gender issues

Trauma specific interventions:

- Survivors need to be respected, informed, supported, connected, and hopeful- in their recovery

- Interrelation between trauma and symptoms of trauma such as substance abuse, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, musculoskeletal presentation, and acute crisis- including suicidal/homicidal ideations (coordination with other service providers)

- Work in a collaborative way with survivors, families, and friends of the survivor, and other service providers in a way that will empower survivors.

Types of trauma are varied, but I usually treat survivors of emotional, verbal, sexual, and medical trauma. I have even treated patients who felt traumatized by other pelvic floor physical therapists (again, no judgment). Since most of my clinical experience includes sexual and medical trauma survivorship, I try to reframe these experiences as potential post-traumatic growth, especially when working with my oncology patients. For my pelvic patients who divulge sexual trauma, I don’t dictate or name anything. I allow the survivor to make the rules and definitions. Survivors of sexual trauma need extra care when treating pelvic floor dysfunction.

First, when treating survivors of sexual trauma: expect ‘characteristically uncharacteristic’ events to occur. These include the psychological/somatic effects of passing out, flashbacks, seizures, tremors, dissociation, and other mechanisms of coping with the trauma. Have a plan ready for these patients.

Triaging the survivor to assess their needs, when trauma has been verbalized/disclosed:

- Are you safe right now?

- Do you need medical treatment right now?

- What do you need to feel in control of (PT session/immediately after disclosure of trauma)?

- You have choices in your treatment and in your response to trauma.

- I believe you.

- Lastly, is this a situation for mandated reporting?

After assisting the survivor in their journey towards healing, it is imperative that you take care of yourself. Make healthy boundaries (with patients and others) and take time to decompress, create healthy ritualistic behaviors, mindfulness/relaxation, and somatic release (like yoga, massage, or working out). These are crucial to successfully treating patients who have experienced trauma and who have shared that trauma experience with you.

Because I use gentle yoga for both my trauma survivors’ treatment and for my own self-care, my course implements evidenced-based trauma-sensitive yoga. Additionally, modifications for manual therapy are explored. The class is designed to be informative and experiential while integrating the Trauma-Informed Approaches of Safety, trustworthiness and transparency, peer support, collaboration and mutuality, empowerment, voice and choice and cultural, historical and gender issues.

Join Lauren Mansell and H&W to learn more in the remote course Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist, scheduled for September 25-26, 2021.