This is a common question that faculty member, Mercedes Eustergerling, is asked. To paraphrase this question – why does H&W (a pelvic rehabilitation institute) offer a breastfeeding course – Breastfeeding Conditions? Well, if you consider that new parents who are breastfeeding have just experienced a birthing event then the answer is – it has plenty to do with pelvic rehabilitation.

Most pelvic therapists have exposure to patients who have given birth and are experiencing a range of postpartum pelvic issues including painful intercourse, prolapse, and incontinence. Have you considered how breastfeeding affects these issues? After giving birth the body’s levels of estrogen drop and the levels of prolactin rise. Prolactin is the hormone responsible for stimulating milk production and will remain elevated during breastfeeding. Thus, estrogen levels remain low during this time and can result in vaginal dryness, delayed menses, low libido, and painful sex.

Women or any person who has experienced childbirth, with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) are often told that the condition will improve after breastfeeding. While many do see improvement after weaning their child there is no correlation between breastfeeding slowing the healing of pelvic floor muscles or worsening POP long-term (1). POP has been linked with sleep quality (2). Which anyone with a newborn can tell you is in short supply. Not surprisingly, sleep is important for your body to recover from birthing, managing postpartum mood disorders, and of course, staying awake to take care of your baby. For breastfeeding parents, sleep deprivation is a way of life as they are waking up every 2-3 hours to feed their baby and establish a strong milk supply. It may be beneficial at this point for the new parent to work with a lactation consultant. These professionals can guide new parents through latching, feeding, milk supply issues, breast pump use, and can help reduce stress and promote optimal rest and recovery postpartum.

Mercedes pointed out in a past interview that “Anytime we talk about breastfeeding we are talking about two people working together, the mother and the baby, it's a team effort. As physiotherapists, we can help with issues or conditions that arise on the maternal (breast) side of things, and on the infant side of things. When it comes down to it, the physiotherapist's role is not about what or how much (nutrition) gets into the baby’s belly, but rather how it gets in (mechanics).” Fast milk flow can make the task of suckling more difficult for babies with an uncoordinated suck/swallow/breathe pattern. If the mechanics or timing is off, the infant will prioritize airway protection and may appear to go on and off the breast throughout the feed.

Another common concern for postpartum parents is urinary incontinence, aka bladder leaking. Breastfeeding does not make incontinence worse, but there is research showing that breastfeeding triggers intense thirst in relation to plasma vasopressin, oxytocin, and osmoregulation (3). The connection is that drinking more water due to this thirst will increase your urge frequency and possible urine leakage.

Mercedes Eustergerling’s remote course Breastfeeding Conditions provides a thorough introduction to the physiology of the lactating breast, dysfunction, treatment interventions, and further discusses the pelvic rehab therapist’s role in breastfeeding and pumping support. As a rehab therapist, it is within the scope of practice to assess and treat breast inflammation and pain such as mastitis, blocked ducts, milk blebs, and cracked nipples. However, Mercedes also discusses when it is important to refer to other health care professionals.

Mercedes sat down with The Pelvic Rehab Report this week to talk about herself and her course.

Tell me a little bit about yourself and your practice.

I studied physical therapy to work with athletes and quickly developed an interest in chronic pain and complex health conditions. As I worked with these populations, I found that I wasn’t able to fully evaluate or treat them without a better understanding of pelvic health, so I took continuing education in pelvic health, and my skills as a physical therapist expanded tremendously.

Then I had a baby and encountered every infant feeding hurdle you can imagine. At our lactation appointments, I was fascinated by it all and realized that I could not provide whole-person physical therapy without understanding the physiology and conditions that are unique to lactating individuals.

In my practice today, I work as a part of a team that provides physical therapy and mental health occupational therapy for chronic pain, trauma, pelvic health, breast health, and infant feeding. We teach courses and workshops, and we do research in chronic pain and breast health.

How do you incorporate physical therapy principles when helping parents meet feeding goals?

At its core, physical therapy is about optimizing a person’s function. What makes physical therapy for infant feeding interesting is that we consider the functional goals and limitations for two individuals: the parent and the infant. In this course, the focus is on the parent’s function. Physical therapists already have the knowledge and skills necessary to manage inflammation, pain, and skin integrity. We apply a biopsychosocial, trauma-informed approach to concerns such as musculoskeletal overuse injuries, ergonomics, breast inflammation, and nipple wounds. Physical therapists are especially helpful for individuals with existing musculoskeletal, neurological, or cardiorespiratory conditions because of our extensive knowledge in these areas

What made you want to create this course?

I was asked to create a course for physical therapy in lactation and infant feeding after attending a women’s health course and discussing it with a colleague. At the time, I was in a solo practice and seeing patients with breast inflammation. They would go onto their parenting groups on Facebook and advise other parents to seek physical therapy for blocked ducts, mastitis, etc. The problem was that I was the only physical therapist in the country providing this service! As physical therapists received requests from their patients to help with these conditions, they started looking for continuing education opportunities.

A lot of our information on lactation comes from oral history that is passed down from one generation to the next. This is a beautiful thing from a cultural perspective. However, one of my goals in creating this course was to provide evidence-based information for health professionals so we could deliver the best care possible. For lactating individuals, there is no shortage of advice or opinions on every topic. I dove into the literature to compile information for a research-informed course and I continue to review the literature and update the course often.

If you could get a message out to practitioners about bodyfeeding and lactation what would it be?

This is a population that is underserved and needs care. In all studies done on the subject, pain is consistently one of the top three reasons for stopping chest/breastfeeding. Physical therapists have unique training and backgrounds that make us a valuable resource for these individuals. It is not difficult to apply our existing knowledge and skills once we gain some understanding of the anatomy, physiology, and sociocultural context of lactation.

What lesson have you learned that has stayed with you and impacted your practice?

When I met one of my first patients with mastitis, she was curled up on the exam table and the lights in the room were off. Her partner answered all my questions because she felt too ill to talk. Two days later, she came to her appointment with makeup on and smiling. She said she was feeling like herself again. I have a great deal of sympathy for anyone experiencing the acute symptoms of breast inflammation and I take care to consider their psychosocial impacts instead of treating it as a purely physical condition.

What do you find is the most useful resource for your practice?

There is a phenomenal community of lactation professionals in my city of Calgary, Canada. We are fortunate to have physicians who specialize in lactation and infant feeding, and they value collaborative care. I shadowed with them in their clinics for 500+ hours and gained a great deal of skills and knowledge from a medical perspective. Now, we continue to collaborate and I am able to refer patients for an evaluation or to check any possible red flags. I encourage all physical therapists entering this practice area to connect with lactation professionals and physicians in their area.

What books or articles have impacted you as a clinician?

The works of Donna Geddes and Maya Bolman have changed my understanding of breast anatomy, physiology, and inflammation. Similarly, the World Health Organization’s publication on mastitis was a great introduction to the pathophysiology and available literature.

A book that I have read several times and recommend to those who are interested in the pediatric side of things is Supporting Sucking Skills in Breastfeeding Infants by Catherine Watson Genna. And in 2021, a book on breastfeeding and public health was published with a chapter on the role of physical therapists, which I wrote. That book is called Lactation: A Foundational Strategy for Health Promotion by Suzanne Hetzel Campbell. The chapter on physical therapy for lactation and infant feeding can be helpful to understand our role and communicate how this practice area fits into our scope of practice.

Breastfeeding Conditions is a two-day remote course and is scheduled for:

This course may be of interest to you if you have taken any other the other H&W peripartum courses including:

- · Pregnancy Rehabilitation

- · Postpartum Rehabilitation

- · Pregnant and Postpartum Rehabilitation Special Topics

- · Doula Services and Pelvic Rehab Therapy

- · Medical Perspective in Peripartum Care

- · Perinatal Mental Health: The Role of Pelvic Rehab Therapist

- · Pregnancy and Postpartum Considerations for High-Intensity Athletics

References:

- Iris S, Yael B, Zehava Y, et al. The impact of breastfeeding on pelvic floor recovery from pregnancy and labor [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 19]. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;251:98-105. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.04.017

- Ghetti C, Lee M, Oliphant S, Okun M, Lowder JL. Sleep quality in women seeking care for pelvic organ prolapse. Maturitas. 2015;80(2):155-161. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.10.015

- James RJ, Irons DW, Holmes C, Charlton AL, Drewett RF, Baylis PH. Thirst induced by a suckling episode during breastfeeding and relation with plasma vasopressin, oxytocin, and osmoregulation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1995;43(3):277-282. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02032.x

Four years ago, I sat with a tiny nugget in my arms and I stared in awe of this beautiful creature. She was perfect, she was amazing, she was… hungry! And I had no idea what to do.

Breastfeeding is at the core of our human experience and it is what defines us as mammals. Have you ever stopped to think about the link between mammal, mammary gland, and mama? And yet, for something so natural, it sure can take a lot of work to figure out.

Breastfeeding is at the core of our human experience and it is what defines us as mammals. Have you ever stopped to think about the link between mammal, mammary gland, and mama? And yet, for something so natural, it sure can take a lot of work to figure out.

In advance of the breastfeeding courses for physical therapists in Phoenix and New Jersey this year, I’ve prepared a list of my favourite myths about breastfeeding. Take a look and tag us on social media if any of them surprised you!

Myth #1: Men can’t breastfeed

We’re starting off with one that seems obvious: surely, men can’t produce milk in sufficient quantities to feed an infant. If they could, then couples around the world would split parenting duties very differently. Right?

Well…

Let’s take a deeper dive into this myth. First, it depends on how you define a man. There are trans men who give birth and then feed their infants. There are also gender nonbinary people who don’t give birth and can still lactate. The permutations of unique situations are plentiful. Some refer to this practice as breastfeeding, while others call it chestfeeding. Ask the individual about their preferred terms, just like you would talk about pronouns. For more information on gender and chestfeeding, check out this article1.

An interesting fact about men and lactation is that domperidone – one of the most common medications in breastfeeding medicine – can contribute to male lactation, even when it is being taken for a different indication2. Domperidone elevates the levels of prolactin, a hormone that signals the lactocytes in the breast to produce milk.

Myth #2: An oversupply of milk is always a good thing

If you’ve looked on postpartum Facebook groups and blogs, you’ve likely seen discussions of undersupply, not having enough milk, and the seemingly uphill battle to make more. There are countless forum posts on switch feeding, power pumping, galactalogues (medications and herbs to increase milk production), etc. Perceived insufficient milk consistently appears among the top reasons for supplementation or breastfeeding cessation3,4,5.

When I was pregnant with my daughter, I made plans to exclusively breastfeed her, pump once a day, and donate the extra milk to a local milk bank. Surely, I thought, the only consequence of making extra milk would be the work involved in making the donations. None of this actually happened but that’s a story for another day.

What I’ve come to learn from working with patients is that in the production of milk, any mismatch of supply and demand can impact a person’s quality of life. Signs of oversupply include6:

- Coughing or gagging during feeds

- Baby is fussy at the breast, possibly crying or arching their back

- Baby is gassy between feeds

- The breasts always feel full

- Recurrent breast inflammation such as blocked ducts and mastitis

- Nipple pain and tissue damage from biting

Fast milk flow can also make the task more difficult for babies with an uncoordinated suck/swallow/breathe pattern. If the mechanics or timing is off, the infant will prioritize airway protection and may appear to go on and off the breast throughout the feed.

Myth #3: For a blocked duct, point the baby’s chin toward the affected area

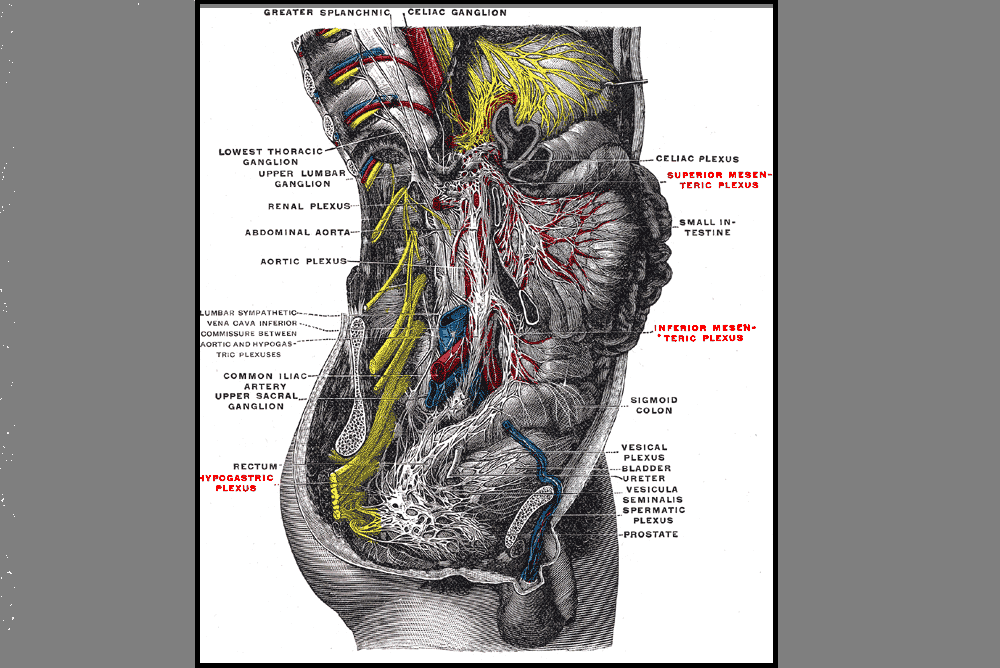

Have you seen it? There’s an image that makes the rounds on social media and it compares the milk-producing components of breast tissue to a flower. This imagery is beautiful, and it sparks conversation every time I see it. If you can’t picture it, think of the milk ducts as the spokes of a bicycle with lobules at the end of each one. They’re neatly arranged in a perfect circle.

If this is how the ducts are arranged, then the infant’s mandible and tongue will draw milk from the affected area during feeds and that will help to resolve the “blockage.” In reality, though, the ducts do not follow straight paths from lobule to nipple. They wind and weave around each other, branching along the way, and milk that comes out the lateral side of the nipple may have originated in the medial part of the breast7.

If this is how the ducts are arranged, then the infant’s mandible and tongue will draw milk from the affected area during feeds and that will help to resolve the “blockage.” In reality, though, the ducts do not follow straight paths from lobule to nipple. They wind and weave around each other, branching along the way, and milk that comes out the lateral side of the nipple may have originated in the medial part of the breast7.

There’s a second reason why the chin pointing won’t resolve a blocked duct: it turns out that there’s no evidence for the existence of a blockage in the first place. We often picture a blocked duct like a coronary artery, with an obstruction that is preventing the flow of milk (or blood) through the vessel. In reality, the ducts are easily collapsible7 and localized inflammation8 and swelling can compress the ducts, preventing milk flow.

Myth #4: Mastitis means infection

Our last myth is perhaps the most pervasive of the list. Many people – including physicians – think that the difference between mastitis and blocked ducts is that mastitis involves a pathogen or infection. Depending on where you live, it may be common practice to prescribe antibiotics for all cases of mastitis.

According to the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine and the World Health Organization, infection is only one of the causes of the condition8,9. Mastitis is defined as inflammation of the breast, which may be infectious or non-infectious in nature. Non-infectious cases can be attributed to mechanical factors such as distension of the breast alveoli and/or chemical factors like pro-inflammatory cytokines entering the parenchyma8.

What this means is that there are many cases of mastitis that can benefit from someone who can help with inflammation management. To me, that sounds like a physical therapist. We have a role to play not only in the local tissue, but also in the biopsychosocial approach that’s required in addressing a person’s pain.

Learn more aboutevidence-based management principles for breastfeeding conditions at the Herman & Wallace course Breastfeeding Conditions: Mastitis, Nipple Pain, and Maternal Factors in Lactation, taking place this year in Phoenix, AZ this March and Princeton, NJ this August. I look forward to discussing these topics and more!

1. MacDonald, T. (2018). Transgender parents and chest/breastfeeding. Retrieved from https://kellymom.com/bf/got-milk/transgender-parents-chestbreastfeeding/

2. Sanis Health Inc. (2015). Domperidone product monograph [PDF file]. Retrieved fromhttps://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00030125.PDF

3. Li, R., Fein, S. B., Chen, J., & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. (2008). Why mothers stop breastfeeding: mothers’ self-reported reasons for stopping during the first year. Pediatrics, 122(Supp. 2), S69-S76.

4. Gatti, L. (2008). Maternal perceptions of insufficient milk supply in breastfeeding. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40(4), 355-363.

5. Ahluwalia, I. B., Morrow, B., & Hsia, J. (2005). Why do women stop breastfeeding? Findings from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System. Pediatrics, 116(6), 1408–1412.

6. La Leche League International (n.d.). Oversupply. Retrieved from https://www.llli.org/breastfeeding-info/oversupply

7. Ramsay, D. T., Kent, J. C., Hartmann, R. A., & Hartmann, P. E. (2005). Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. Journal of anatomy, 206(6), 525-534.

8. World Health Organization. (2000). Mastitis: causes and management (No. WHO/FCH/CAH/00.13). World Health Organization.

9. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol Committee. (2008). ABM clinical protocol# 4: mastitis. Breastfeeding Medicine, 3(3), 177-180.