I recently found this article from the Psychology Research and Behavior Management Journal. I found myself curious about how other healthcare disciplines treat a diagnosis that often presents in conjunction with pelvic floor dysfunction. Irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, affects nearly 35 million Americans. It is considered a ‘functional’ condition meaning that symptoms occur without structural or biochemical pathology. There is often a stigma with functional diagnosis that the symptoms are “all in their heads”, and while there are many theories about what predisposes individuals to IBS, the experts now think of IBS as a “disorder of gut brain interaction”. Generally, there are 3 subtypes of IBS where people note either constipation dominant, diarrhea dominant or mixed. In order to be diagnosed an individual must report abdominal pain at least 1 day per week in the last 3 months which is related to stooling and a change in frequency or form. Other symptoms that are common are bloating, nausea, incomplete emptying, and urgency.

The author suggests a biopsychosocial framework to help understand IBS. An interdependent relationship between biology (gut microbiota, inflammation, genes), behavior (symptom avoidance, behaviors), cognitive processes (“brain-gut dysregulation, visceral anxiety, coping skills”), and environment (trauma, stress). The brain-gut connection by a variety of nerve pathways is how the brain and gut communicate in either direction; top down or bottom up. Stress and trauma can dysregulate gut function and can contribute to IBS symptoms.

Stress affects the autonomic nervous system that contributes to sympathetic (fight/flight) and parasympathetic (rest/digest). Patients with IBS may have dysfunction with autonomic nervous system regulation. Symptoms of dysregulated gut function can present as visceral hypersensitivity, visceral sensitivity, and visceral anxiety. Visceral hypersensitivity is explained as an upregulation of nerve pathways. The author sites studies that note that IBS patients have a lower pain tolerance to rectal balloon distention than healthy controls. Visceral sensitivity is another sign of upregulation where IBS patients have a greater emotional arousal to visceral stimulation and are less able to downregulate pain. The author notes that the IBS population show particular patterns of anxiety with visceral anxiety and catastrophizing. Visceral anxiety is described hypervigilance to bowel movements and fear avoidance of situational symptoms. For example, fear of not knowing where the bathroom is located.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be an effective treatment to decrease the impact of IBS symptoms. CBT is focused on modifying behaviors and challenging dysfunctional beliefs. CBT can be presented in a variety of ways, however most include techniques consisting of education of how behaviors and physiology interplay for example the gut and stress response; relaxation strategies, usually diaphragmatic breathing and progressive relaxation; cognitive restructuring to help individuals see the relationship between thought patterns and stress responses; problem-solving skills with shift to emotion focused strategies (“acceptance, diaphragmatic breathing, cognitive restructuring, exercise, social support”) instead of problem focused strategies, and finally exposure techniques to help the individual slowly face fear avoidance behaviors. So much of the techniques are similar to what pelvic floor therapists try to educate our patients in. It is reassuring to me that through we may be different disciplines we are on the same team are moving towards the same goal. The author recommends a 10 session treatment duration, and notes that may be a barrier for some. Integrated practice with other healthcare professionals is also recommended. The more we can know about what our other team members are doing to help support patients the more effective we all are.

Kinsinger, Sarah W. “Cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome: current insights” Psychology research and behavior management vol. 10 231-237. 19 Jul. 2017, doi:10.2147/PRBM. S120817

Andrea Wood, PT, DPT, WCS, PRPC is a pelvic health specialist at the University of Miami downtown location. She is a board certified women’s health clinical specialist (WCS) and a certified pelvic rehabilitation practitioner (PRPC). She is passionate about orthopedics and pelvic health. In her spare time, you can find her enjoying the south Florida outdoors.

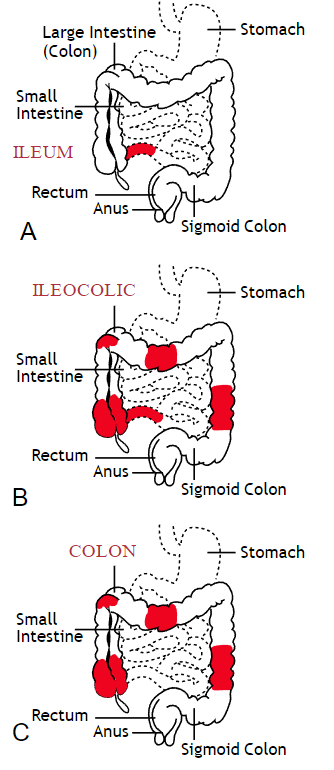

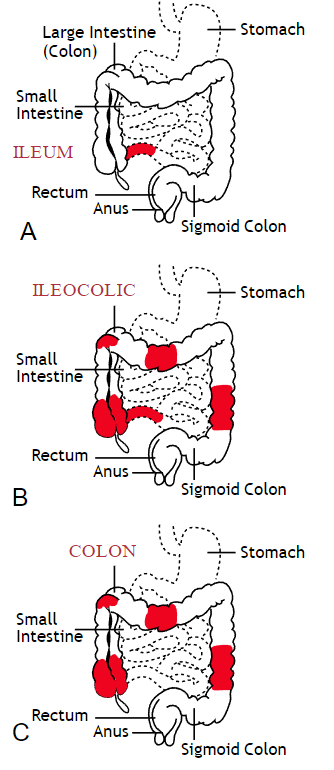

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes the two diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. While both can cause similar health effects, the differences of the disease pathologies are listed below:1

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease | |

| Affected Area |

|

|

| Pattern of Damage |

|

|

Common complications experienced by patients with IBD include fecal incontinence, fecal urgency, night time soiling, urinary incontinence, abdominal pain, hip and core weakness, pelvic pain, fatigue, osteoporosis, and sarcopenia. In a sample of 1,092 patients with Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, or unclassified IBD, 57% reported fecal incontinence. Fecal incontinence was reported not only during periods of flare ups, but also during remission periods.2 One common factor affecting fecal incontinence is external anal sphincter fatigue. External anal sphincter fatigue has also been shown to be present in IBD patients who are not experiencing fecal incontinence or fecal urgency. IBD patients have been shown in studies to have similar baseline pressures versus healthy matched controls, thus indicating the possibility that deficits in endurance versus strength can play a larger role in fecal incontinence.3 Other factors contributing to fecal incontinence include post inflammatory changes that may alter anorectal sensitivity, anorectal compliance, neuromuscular coordination, and cause visceral hypersensitivity. Visceral hypersensitivity may be caused by continuous release of inflammatory mediators found in patients with IBD. It is also important to screen properly for incomplete bowel emptying and stool consistency to rule out overflow diarrhea or fecal impaction. Reports of need to splint digitally for full evacuation may indicate incomplete bowel emptying and defaectory disorders such as paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle or rectocele. Anorectal manometry testing may be highly useful in identifying patients likely to improve from biofeedback therapy.4

Urinary incontinence can also be another secondary consequence to IBD. In a sample of 4,827 patients with IBD, 1/3 of responders reported urinary incontinence that was strongly associated with the presence of fecal incontinence. Frequent toilet visits for defecation may stimulate overactive bladder. Women were more likely to experience fecal incontinence versus men. One possible mechanism for increased fecal incontinence in women is men often have a longer and more complete anal sphincter that may be protective of fecal incontinence.5

Physical activity has been shown to be lower in patients with IBD versus healthy controls. 6, 7 Guiding IBD patients in proper exercises programs can have great benefits. Exercise may reduce inflammation in the gut and maintain the integrity of the intestines, reducing inflammatory bowel disease risk.8 It can also help increase bone mass density, an important factor in IBD patients who are at greater risk for osteoporosis. It has also been shown to help general fatigue in IBD patients. Patients with Crohn’s disease who participate in higher exercise levels may be less likely to develop active disease at 6 months. Treadmill training at 60% VO2 max and running three times a week has not been shown to evoke gastrointestinal symptoms in IBD patients. An increase of BMI predicts poorer outcomes and shorter time to first surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease.6

Conservative physical therapy interventions for treating IBD symptoms can include the following:

| Symptoms resulting from IBD | Physical Therapy Interventions |

| Fecal Incontinence (FI) |

|

| Urinary urgency |

|

| Sarcopenia |

|

| Fatigue |

|

| Pelvic Pain |

|

Surgical interventions for IBD are dependent upon what type of disease the patient has and what areas of the intestines are affected the most. Surgery may be considered once the disease has become non responsive to medication therapy and quality of life continues to decline. A colectomy involves removing the colon while a proctocolectomy involves both removal of the colon and rectum. For ulcerative colitis patients, options include total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy or a restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Restorative proctocolectomy eliminates the need for an ostomy bag making it the preferred surgery of choice if possible and gold standard for ulcerative colitis patients.10 For patients with Crohn’s disease, options include resection of part of the intestines followed by an anastomosis of the remaining healthy ends of the intestines, widening of the narrowed intestine in a procedure called a strictureplasty, colectomy or proctocolectomy, fistula repair, and removal of abscesses if needed.11

1. Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. 2019. What is Crohn’s Disease. Retrieved from: http://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-are-crohns-and-colitis/what-is-crohns-disease/

2. Vollebregt PF, van Bodegraven A, Markus-de Kwaadsteniet T, et al. Impacts on perianal disease and faecal incontinence on quality of life and employment in 1092 patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2018; 47: 1253-1260

3. Athanasios A, Kostantinos H, Tatsioni A et al. Increased fatigability of external anal sphincter in inflammatory bowel disease: significance in fecal urgency and incontinence. J Crohns Colitis (2010) 4: 553-560.

4. Nigam G, Limdi J, Vasant D. Current perspectives on the diagnosis and management of functional anorectal disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 6: doi: 10.1177/1756284818816956

5. Norton C, Dibley L, Basset P. Faecal incontinence in inflammatory bowel disease: Associations and effect on quality of life. J Crohn’s Colitis. (2013) 7, e302-e311.

6. Biliski J, Mazur-Bialy A, Brzozowski B et al. Can exercise affect the course of inflammatory bowel disease? Experimental and clinical evidence. Pharmacological Reports. 2016 (68): 827-836.

7. Tew G, Jones K, Mikocka-Walus A. Physical activity habits, limitations, and preditors in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a large cross-sectional online survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22(12): 2933-2942.

8. Vincenzo M, Villano I, Messina A. Exercise modifies the gut microbiota with positive health effects. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevitiy. 2017: Article ID 3831972.

9. Cramer H, Schafer M, Schols M. Randomised clinical trial: yoga vs written self care advice for ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 45: 1379-1389.

10. Cornish J, Wooding K, Tan E, et al. Study of sexual, urinary, and fecal function in females following restorative proctocolectomy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 18 (9) 2012. 1601-160

11. Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. 2019. Surgery Options. Retrieved from: http://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-are-crohns-and-colitis/what-is-crohns-disease/surgery-options.html

Reports in the media of research on mindfulness keep reminding us that mindfulness has positive effects on a wide variety of conditions. In the world of pelvic rehabilitation, which is broad when we consider the scope of the patient populations and diagnoses that we treat, we can find benefits from mindfulness to include bladder dysfunction, pain, and even bowel dysfunction. When specifically addressing bowel dysfunction, there are many studies that promote the benefits of mindfulness on bowel health, including the following research findings for the following topics:

Colitis

In 53 patients diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC), some were randomized into a control group or a treatment arm that consisted of instruction in mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). While mindfulness-based stress reduction did not, in this study, affect the flare-ups of patients with moderately severe ulcerative colitis, the MBSR “…had a significant positive impact on the quality of life…” when compared to patients in the control group. So even though the use of mindfulness did not appear to affect the disease, the patients utilizing mindfulness perceived a higher quality of life even during a flare of their colitis. (Jedel et al., 2014)

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

In another study, 36 people (24 diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and 12 healthy subjects in control group) were studied. The patients who had IBS were divided into equal groups and were treated with either CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) or MBT (mindfulness-based treatment.) The authors conclude that mindfulness-based therapy “…is an effective method to decrease symptoms of patients with IBS…” and that it was more effective than CBT at the 2 month follow-up. (Zomorodi et al., 2014)

Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD)

In reference to the importance of addressing mind, body and spirit for patients who have inflammatory bowel disease, this article discusses the benefits of addressing the psychosocial impacts of gastrointestinal disorders, as the disorders are “…best understood by a combination of genetic, physical, physiological, and psychological factors.” (Jedel et al., 2012)

Functional Gastrointestinal (GI) Disorders

Although a recent analysis of studies on gastrointestinal disorders calls for improvement in methodological quality of the research, the article concludes that “…mindfulness-based interventions may be useful in improving FGID [functional gastrointestinal disorders] symptom severity and quality of life with lasting effects…” (Aucoin et al., 2014)

From these few studies we can see that mindfulness is an accepted and potentially helpful adjunct in improving patient symptoms and quality of life in those who have bowel dysfunction. Mindfulness is a tool that every therapist should have in the toolbox for offering to patients who can complete this self-care activity as part of a home program. If you’d like to learn more about how to effectively instruct in mindfulness, you still have time to register for the Caroline McManus continuing education course on Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment, taking place January 16-17 in Silverdale, Washington, on the beautiful peninsula.

Aucoin, M., Lalonde-Parsi, M. J., & Cooley, K. (2014). Mindfulness-Based Therapies in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014.

Jedel, S., Hankin, V., Voigt, R. M., & Keshavarzian, A. (2012). Addressing the mind, body, and spirit in a gastrointestinal practice for inflammatory bowel disease patients. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 10(3), 244-246.

Jedel, S., Hoffman, A., Merriman, P., Swanson, B., Voigt, R., Rajan, K. B., ... & Keshavarzian, A. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to prevent flare-up in patients with inactive ulcerative colitis. Digestion, 89(2), 142-155.

Zomorodi, S., Abdi, S., & Tabatabaee, S. K. R. (2014). Comparison of long-term effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus mindfulness-based therapy on reduction of symptoms among patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from bed to bench, 7(2), 118.