Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC is the author and presenter of the new Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation course, and she is the co-author of the Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab course. She is a certified LSVT (Lee Silverman) provider and faculty member, and is a trained PWR! (Parkinson’s Wellness Recovery) provider, both focusing on intensive, amplitude and neuroplasticity based exercise programs for people with Parkinson disease. Erica partners with the Wisconsin Parkinson Association (WPA) as a support group and event presenter as well as author in their publication, The Network. Erica has taken a special interest in the unique pelvic floor, bladder, bowel and sexual health issues experienced by individuals diagnosed with Parkinson disease.

The pharmacologic management of non-motor autonomic dysfunction, including urinary, bowel, and sexual health impairments, is often ineffective, not supported by adequate research, or causes intolerable side effects for people with Parkinson disease. In a recent article titled Update on Treatments for Nonmotor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease – An Evidence-Based Medicine Review Seppi, K, et al., 2019, the authors state that “before attempting any [pharmacological] treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms, urinary tract infections, prostate disease in men, and pelvic floor disease in women should be ruled out.” It is rare to see a mention of pelvic floor within the literature that addresses helping people with Parkinson disease.

Pelvic rehabilitation specialists have a unique opportunity to step in and help these individuals improve their quality of life and many neurologists are unaware of the benefits our services could provide for their patients. Please join me in an exciting dive into understanding the physiology of how Parkinson disease affects a person’s pelvic health and develop your skills to effectively assess and develop treatment plans to change the life of these individuals.

Seppi, K., Ray Chaudhuri, K., Coelho, M., Fox, S. H., Katzenschlager, R., Perez Lloret, S., ... & Hametner, E. M. (2019). Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease—an evidence‐based medicine review. Movement Disorders, 34(2), 180-198

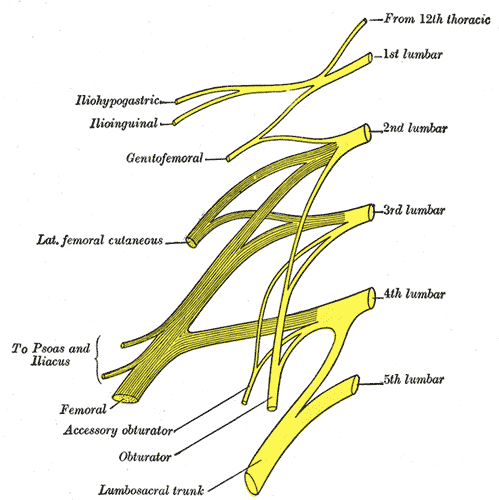

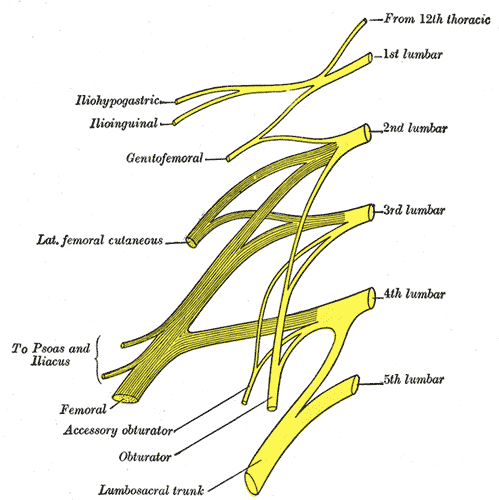

The lumbar sacral nerve plexus can be divided into the direction the nerves travel, either anterior or posterior. This post will focus on anterior hip nerves. I remember writing about the brachial plexus over and over in physical therapy school, but only a few times for the lumbosacral plexus. Patients frequently report anterior hip and pubic pain and can often have signs and symptoms of nerve entrapment. This article orients the reader to links between signs and symptoms and examination to help appropriately diagnosis specific nerves in the athletic population.

The obturator, femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous are more commonly entrapped in sports injuries. Although the three nerves that travel together through the inguinal canal (ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral) are less common, however surgery can create nerve entrapment sequelae.

The obturator, femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous are more commonly entrapped in sports injuries. Although the three nerves that travel together through the inguinal canal (ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral) are less common, however surgery can create nerve entrapment sequelae.

There are a few places where the obturator nerve can become squished. Typically, as it leaves the obturator canal which presents at medial thigh pain, and then again in the fascia of the adductors which presents as pain with abduction. The challenge is to differentiate between the nerve and adductor strain. Obturator nerve entrapment will test positive with passive hip abduction and extension, but negative resisted hip adduction.

The femoral nerve can become entrapped in a kind of compartment syndrome as it goes between the psoas and iliacus. This can lead to compression to the neurovascular bundle with resultant swelling, edema, and ischemia. Signs of femoral nerve compression include anterior thigh numbness and paresthesias. Occasionally, this can also include the saphenous nerve with symptoms continuing along medial knee to foot. Femoral nerve entrapment can create quadricep muscle weakness and atrophy, with diminished or absent patella tendon reflexes. Symptoms are reproduced with hip extension and knee flexion thereby elongating the femoral nerve.

The lateral femoral cutaneous (LFC) nerve is sensory. Diagnosed as meralgia paresthetica, the LFC nerve is typically entrapped where it penetrates under the inguinal ligament just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). Symptoms include numbness, tingling, hypersensitivity to touch, burning along outer thigh along the iliotibial band. The LFC nerve can often be compressed by wearing heavy belts (scuba divers, construction belts, etc). Special tests that indicate LFC are pelvic compression in side lying with involved side up to slack the inguinal ligament and Tinels sign.

Anterior hip pain is fairly common in pelvic floor patients. Differential diagnosis and treatment of these anterior nerves can allow patients to return to full daily function. To learn manual assessment and treatment techhniques for the lumbar nerves, consider attending Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment.

Martin R, Martin HD, Kivlan BR. Nerve Entrapment In The Hip Region: Current Concepts Review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Dec;12(7):1163-1173.

I recently assisted at a Pelvic Floor Level 2B course which has been updated with recent research, new sections, and less repetition from Pelvic Floor Level 1. In the course they mentioned this article which sparked a lively discussion and I had to learn more. It is rare to see a study with a large number of participants in pelvic health and especially with a vaginismus diagnosis.

Vaginismus is defined as a genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder along with dyspareunia under the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; Fifth Edition) in which penetration is often impossible due to pain and fear. Vaginismus is both a physical and psychological disorder as it exhibits both muscle spasms and fear/anxiety of penetration. Symptoms vary by severity. Common presentation is an inability or discomfort to insert/remove a tampon, pain with penetration, and complaints of “hitting a wall” in attempted penetration; and inability to participate in gynecological exams.

The authors of this study evaluated the severity of vaginismus. The penetrative history was used in addition to presentation at pelvic exam, and then given a level. There are 2 grading systems, Lamont and Pacik, that indicate the level of fear and anxiety about being touched. They found that those with severe vaginismus were Lamont levels 3 and 4, and Pacik level 5. For example, a Pacik Level 5 includes Lamont grade 4 “generalized retreat: buttocks lift up; thighs close, patient retreats” plus a visceral reaction such as “palpitations, hyperventilation, sweating, severe trembling, uncontrollable shaking, screaming, hysteria, wanting to jump off the table, a feeling of going unconscious, nausea, vomiting and even a desire to attack the doctor”.

The authors of this study evaluated the severity of vaginismus. The penetrative history was used in addition to presentation at pelvic exam, and then given a level. There are 2 grading systems, Lamont and Pacik, that indicate the level of fear and anxiety about being touched. They found that those with severe vaginismus were Lamont levels 3 and 4, and Pacik level 5. For example, a Pacik Level 5 includes Lamont grade 4 “generalized retreat: buttocks lift up; thighs close, patient retreats” plus a visceral reaction such as “palpitations, hyperventilation, sweating, severe trembling, uncontrollable shaking, screaming, hysteria, wanting to jump off the table, a feeling of going unconscious, nausea, vomiting and even a desire to attack the doctor”.

241 patients participated in this study, with a mean duration of 7.8 years. 70% of participants were a Lamont level 4 or Pacik level 5 at baseline. The authors looked at previous treatments tried and coping strategies; 74% had tried lube, 73% had tried dilators, 50% had tried Kegels, 28% had tried physical therapy, 3% had tried a surgical vestibulectomy. The full table 2 is in the article. Most participants had a mean of at least 4 failed treatments.

The aim was to help these women to achieve pain free intercourse after treatment. In order to tolerate the treatment, many were sedated with midazolam before the Q-tip test, and more sedation given as needed. The treatment lasted for about 30 minutes and consisted of:

- Q-tip test with as minimal sedation as possible to rule out vulvodynia and provoked vestibulodynia

- Digital exam of tolerance in order to assess the level of spasm in introitus. Graded 0 (no spasm) to 4 (severe spasm where digital insertion was difficult)

- Botox 50 U injections to right and left submucosal space near the bulbospongiosus muscle administered with a pediatric speculum placed. Additional Botox was injected submucosally into levator ani muscles if also in spasm/tight

- Injections 0.25% bupivacaine (a numbing agent) 1 mL increments along right and left lateral vaginal walls (9 mL per side) from cervix to introitus

- Progressive dilation; circumference 3 inches (#4), 4 inches (#5), 5 inches (#6)

- Reassessed with digital examination

- Re-insert #5 or #6 dilator and patient was awakened and taken to recovery

If the patient consented, her partner could be present during the procedure and was allowed to palpate the level of spasm with gloved digit and was educated on dilator insertion. The authors noted that many partners had a ‘profound’ experience.

A nurse worked with the couple for about two hours in the recovery room to help them be more comfortable moving the dilator in and out with minimal-to-no pain as the numbing agent lasts 6-8 hours. Three participants were treated each time and consented to meet each other. Patients were discharged with #4 dilator in place and asked to keep in until the next day. They were given Ibuprofen and sleeping aids as needed.

Day 1

Participants return with partners and progress up to larger sizes (#5 and #6). They participate in group counseling with the primary researcher Dr. Pacik. This lasted about 5 hours; and consisted of education of dilator progression, returning to intercourse and lubricants. If participants wished to have private counseling instead that was granted. Many exchanged contact information. They were encouraged to continue seeing their healthcare clinicians as indicated; sex therapists, physical therapists, psychologists.

Dilator Progression

Month 1

- 2 hours of dilator per day. Either in 1 sitting or 1 hour of dilator work x2 per day

- Progress to bigger sizes until #5 or #6 is comfortable

Month 2

- 1 hour of dilator use per day and continue toward larger sizes

Month 3

- 15-30 minutes of dilator use per day

Months 4-12

- 10-15 minutes of dilator use per day or every other day

During the counseling session post-procedure, the recommendations for returning to intercourse included:

- Delaying intercourse until #5 dilator was able to be easily inserted

- It is helpful to do 1 hour of dilator work before attempting intercourse for the first time

- If partner’s penis is larger progress to larger dilators (#7 - 6 inch circumference or #8 7 inch circumference)

- Goal of the first few attempts is to insert tip of dilator only

- Once tip can be inserted easily then progress to full penetration; restrain from thrusting

- Try “spooning position” if ‘leg lock’ occurs

- Try different positions with dilator work and intercourse to see what works best

71% of participants achieved pain-free coitus 5 weeks after the procedure. 2.5% could not achieve coitus within one-year period although they could use #5 or #6 dilators. The participants were given a validated outcome tool, the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), before and after the procedure and at 1-month, 3-months, 6-months, and 1-year; with significant improvement at each interval. The patients were followed for one year, and often remained in contact with the authors for much longer ranging from 16-months to 9-years.

The authors propose that use of dilators at the time of botox and post procedure counseling and support help participants ‘break through’, whereas previous treatment may not be as multidimensional and limit efficacy. Botox lasts 2-4 months and allowed for dilation progression.

Initially after reading this article the treatment seemed a little drastic to me, but then I considered the women with this level of vaginismus are often not coming into my clinic. They may need this level of structure, consistently, and multidimensional treatment as half measures have failed them. I am so glad they were persistent and found the help they needed.

Pacik, P., Geletta, S. Vaginismus Treatment: Clinical Trials Follow Up 241 Patients. Sex Med 2017;5:e114-e123

Leeann Taptich DPT, SCS, MTC, CSCS is Co-Author of the new Herman & Wallace offering, Breathing and Diaphragm: Pelvic and Orthopedic Therapist. Leeann leads the Sports Physical Therapy team at Henry Ford Macomb Hospital in Michigan where she mentors a team of therapists. She also works very closely with the pelvic team at the hospital which gives her a very unique perspective of the athlete.

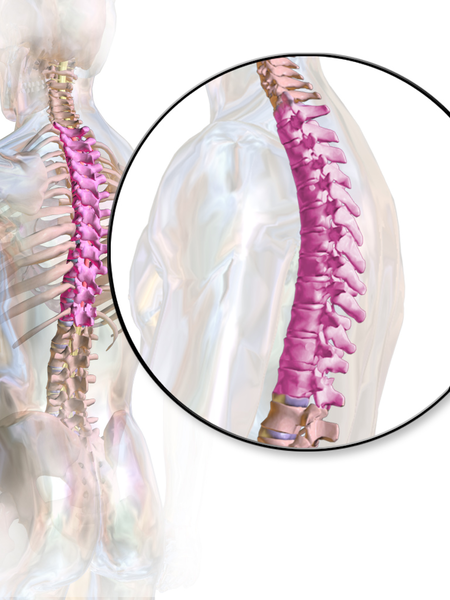

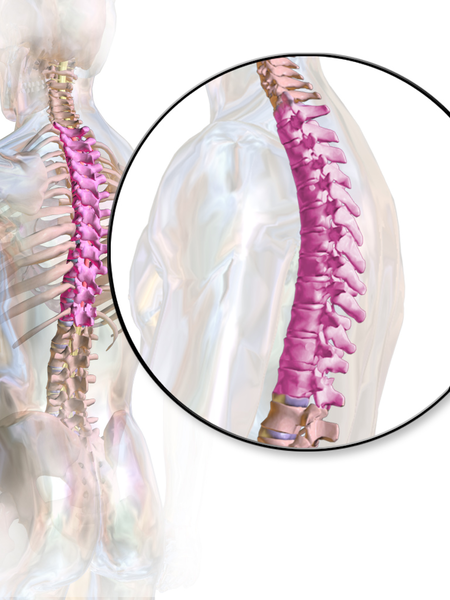

According to a paper from Manual Therapy, the thoracic spine is the least understood part of the spine, despite the huge role it plays in both movement and in regulation of our Autonomic Nervous System.1 Researchers found that the thoracic spine is the least studied of the three spinal regions; thoracic, cervical, and lumbar. I am frequently asked by fellow therapists for help in objectively assessing and treating the thoracic region which has led to the realization that even amongst experienced therapists the thoracic spine’s importance is less understood especially in terms of its function.

According to a paper from Manual Therapy, the thoracic spine is the least understood part of the spine, despite the huge role it plays in both movement and in regulation of our Autonomic Nervous System.1 Researchers found that the thoracic spine is the least studied of the three spinal regions; thoracic, cervical, and lumbar. I am frequently asked by fellow therapists for help in objectively assessing and treating the thoracic region which has led to the realization that even amongst experienced therapists the thoracic spine’s importance is less understood especially in terms of its function.

Anatomically, the thoracic spine along with the ribs and sternum provide a frame that supports and protects the lungs and heart. Despite the rigidity that is required to fulfill that function, the thoracic spine contributes significantly to a person’s ability to rotate.2

One of the biggest roles the thoracic spine plays is in the regulation of the Sympathetic Nervous System, which is a part of the Autonomic Nervous System. The sympathetic nervous system, also known as the “Fight or Flight” system is in overdrive in our patients who present with pain. One of the many complications that arise from an upregulated sympathetic system is increased respiratory rate and/or dysfunctional breathing.3 Carefully applied manual therapy techniques to the thoracic region can help regulate the Autonomic Nervous System by affecting the diaphragm, the intercostals, and other respiratory musculature.4 Specific thoracic mobilizations/manipulations can improve respiratory function.4

In the Breathing and Diaphragm course, Aparna Rajagopal and I discuss the importance of the thoracic spine from both a regional and global perspective. Thoracic spine assessment is taught along with multiple mobilization techniques and manipulations all of which will help the clinician link the thoracic spine to the treatment of pelvic pain, low back pain, and breathing pattern disorders. Join Aparna and I in either Sterling Heights, MI this March or Princeton, NJ in December for Breathing and the Diaphragm: Pelvic and Orthopedic Therapists: From Assessment to Clinical Applications for Pelvic and Orthopedic Therapists!

1. Heneghan NR, Rushton A. Understanding why the thoracic region is the ‘Cinderella’ region of the spine. Man Ther. 2016; 21: 274-276.

2. Narimani M, Arjamand N. Three-dimensional primary and coupled range of motions and movement coordination of the pelvis, lumbar, and thoracic spine in standing posture using inertial tracking device. Journal of Biomechanics. 2018; 69: 169-174.

3. Bernston GG. Stress effects on the body: Nervous system. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/stress/effects-nervous. January 18, 2020.

4. Shin DC, Lee YW. The immediate effects of spinal thoracic manipulation on respiratory functions. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2016; 28: 2547-2549.

Pelvic pain is a common diagnosis that we see as pelvic floor therapists. Pelvic pain is pain located in the lower abdomen, but above pubic symphysis, and is associated with various causes; myofascial pain, neuropathies, endometriosis, painful bladder, and irritable bowel syndromes. A common symptom of pelvic pain is deep dyspareunia or pain with deep vaginal penetration. Vulvar pain is different, as it is below pubic symphysis, and has several sub-classifications. These sub-classifications can often be confusing. The National Vulvodynia Association has a free online education that explains the different sub-types very succinctly. This article focuses on provoked vestibulodynia, which is the most commonly studied.

PVD or Provoked Vestibulodynia often has superficial dyspareunia which can negatively affect sexual functioning, which can lead to changes in psychological function and quality of life. Women with PVD often complain of greater pain during and after intercourse, pain catastrophization, and allodynia when compared to women with superficial dyspareunia but without PVD. These symptoms indicate central nervous system upregulation or sensitivity. This study sought to investigate the impact of these symptoms.

PVD or Provoked Vestibulodynia often has superficial dyspareunia which can negatively affect sexual functioning, which can lead to changes in psychological function and quality of life. Women with PVD often complain of greater pain during and after intercourse, pain catastrophization, and allodynia when compared to women with superficial dyspareunia but without PVD. These symptoms indicate central nervous system upregulation or sensitivity. This study sought to investigate the impact of these symptoms.

Pelvic pain encompassed a variety of complaints: “dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, dyschezia, chronic pelvic pain, back pain, or diagnosed or suspected endometriosis”. Participants were excluded if postmenopausal or if self reported never sexually active.

One hundred twenty nine participants were divided into those with pelvic pain and PVD (43), and those with pelvic pain alone (87). For this study PVD was diagnosed as superficial dyspareunia (>4/10) and positive Q-tip test with a fixed pressure of 30g. Those with did not meet this criteria were considered to have pelvic pain alone.

The two groups were compared for superficial and deep sexual discomfort severity, sexual quality of life; fear avoidance, feelings of guilt, frustration, etc, physical examination of trigger points along abdominal wall (positive Carnett test), and numeric pain scale of various painful lumbo-pelvic regions.

Of the 129 participants notable findings in both the two groups include 31% had confirmed endometriosis, 40% suspected of endometriosis, and in the remaining 18% had no confirmed or suspected endometriosis. The authors found that the pelvic pain + PVD group had significantly more superficial dyspareunia (p=<.001) and deep dyspareunia (p=.001) which was rated >7/10 for both. This group was also had greater (3x more likely to have) depression symptoms, greater anxiety, and catastrophizing, and was more likely to have painful bladder syndrome than the pelvic pain alone group. There were no differences between the two groups for irritable bowel syndrome or abdominal wall tenderness.

This research is consistent with other research findings. The authors explore various causes of the findings including; cross- sensitization - where there may be cross talk of nerve signals from viscera to viscera and viscera to muscular structures that converge in the spinal cord. The authors note that the poor relationship between PVD and irritable bowel and PVD and abdominal wall tenderness limit that theory. They explore the psychological symptoms may be a consequence of pelvic pain or it may be that having anxiety/depression may make women more sensitive to developing pelvic pain and PVD. This sounds like a little chicken or egg theory. The authors suggest that those with PVD and pelvic pain may benefit from a more intensive multi-disciplinary approach including; “medical, surgical, psychological, or physical therapy approaches”.

Bao, C., Noga, H, Allaire, C. et al. “Provoked Vestibulodynia in Women with Pelvic Pain” Sex Med 2019; 1-8

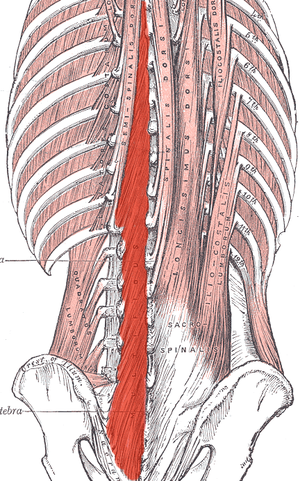

If you work with orthopedic patients, I am sure that you have had a back-pain patient that you have discharged, only for them to return a year later suffering from another episode of pain. We all know that once someone suffers from a back injury, they are more likely to develop a chronic issue. Even patients with insidious back pain and no specific injury often develop chronic issues and can have pain that waxes and wanes after the initial episode.

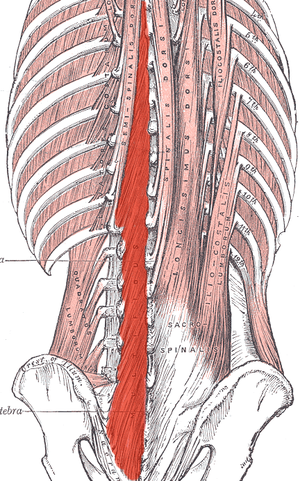

What happens in the body to cause this? Most of us have learned that the pelvic floor, transverse abdominus, and the deep fibers of the lumbar multifidus play an important role in stabilization. With injury, these muscles can become less effective in stabilizing the spine and pelvis. Studies have shown that muscle atrophy in the lumbar multifidus has been shown to occur with injuries and persist after resolution of the pain.1

What happens in the body to cause this? Most of us have learned that the pelvic floor, transverse abdominus, and the deep fibers of the lumbar multifidus play an important role in stabilization. With injury, these muscles can become less effective in stabilizing the spine and pelvis. Studies have shown that muscle atrophy in the lumbar multifidus has been shown to occur with injuries and persist after resolution of the pain.1

I recently did additional research to find out other reasons that cause these local stabilizing muscles to not function optimally. I found that these muscles also can suffer from arthrogenic muscle inhibition after an episode of low back pain.2 Arthogenic inhibition is a deficit in neural activation to a muscle. It is thought to occur due to a change in the discharge of articular sensory receptors due to swelling, inflammation, joint laxity, and damage to afferent nerves.2 EMG studies have shown reduced neural activity in the deeper fibers of the multifidus in patients with back pain.3

Another thing that fascinated me was that cortical changes in the brain also occur with low back pain. Changes in cortical representation of the multifidus and the body’s ability to voluntarily activate the muscle has been noted.4 Motor retraining has been shown to reorganize the motor cortex with regards to the transverse abdominus.5 Also, improvement in brain organization and function occurs after resolution of back pain.6

This is good news for patients! As therapists, we may not be able to do anything with respects to arthogenic inhibition. However, we can work on motor retraining for the core muscles. It has been shown that specific training that targets the multifidus can restore the neural activity to the multifidus and lead to improvement of pain and function.7,8 Training the multifidus can be difficult for therapists to teach. However, studies have found that ultrasound guided biofeedback is helpful for patients to learn to contract their multifidus.9,10

Come learn more about the multifidus and how it relates to back pain and stability. In Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging: Women's Health and Orthopedic Topics we will go over how to help your patients learn to activate and strengthen their multifidus. Join me on February 28 - March 1st in Raleigh, NC to learn new ways to help your patients!

1. Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first‐episode low back pain. Spine 1996;21:2763–2769.

2. Russo M, Deckers K, Eldabe S, et al. Muscle control and non-specific chronic low back pain. Neuromodulation: Technology at the neural interface. 2018; 21 (1): 1-9.

3. D'Hooge R, Hodges P, Tsao H, Hall L, Macdonald D, Danneels L. Altered trunk muscle coordination during rapid trunk flexion in people in remission of recurrent low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2013;23:173–181

4. Massé‐Alarie H, Beaulieu L‐D, Preuss R, Schneider C. Corticomotor control of lumbar multifidus muscles is impaired in chronic low back pain: concurrent evidence from ultrasound imaging and double‐pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. Exp Brain Res 2015; 234:1033–1045.

5. Tsao H, Galea MP, Hodges PW. Driving plasticity in the motor cortex in recurrent low back pain. Eur J Pain 2010;14:832–839.

6. Seminowicz DA, Wideman TH, Naso L et al. Effective treatment of chronic low back pain in humans reverses abnormal brain anatomy and function. J Neurosci 2011;31:7540–7550

7. França FR, Burke TN, Caffaro RR, Ramos LA, Marques AP. Effects of muscular stretching and segmental stabilization on functional disability and pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012;35:279–285.

8. Goldby LJ, Moore AP, Doust J, Trew ME. A randomized controlled trial investigating the efficiency of musculoskeletal physiotherapy on chronic low back disorder. Spine. 2006;31:1083–1093.

9. Ghamkhar L, Emami M, Mohseni‐Bandpei MA, Behtash H. Application of rehabilitative ultrasound in the assessment of low back pain: a literature review. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2011;15:465–477.

10. Van K, Hides JA, Richardson CA. The use of real‐time ultrasound imaging for biofeedback of lumbar multifidus muscle contraction in healthy subjects. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36:920–925

Childbirth fear is associated with lower labor pain tolerance and worse postpartum adjustment.1,2 In addition, psychological distress during pregnancy is associated with adverse consequences in offspring, including detrimental birth outcomes, long-term defects in cognitive development, behavioral problems during childhood and high levels of stress-related hormones.3 These negative consequences of fear and stress during pregnancy have inspired both interest and research into the role of mindfulness training during pregnancy to reduce fear and stress and improve outcomes.

In a randomized controlled trial, first-time mothers in the late 3rd trimester of pregnancy were randomized to attend either a 2.5-day mindfulness-based childbirth preparation course offered as a weekend workshop or a standard childbirth preparation course with no mind-body focus.4 Participants completed self-report assessments pre-intervention, post-intervention, and post-birth, and medical record data were collected. Compared to standard childbirth education, those in the mindfulness-based workshop showed greater childbirth self-efficacy and mindful body awareness, reduced pain catastrophizing and lower post-course depression symptoms that were maintained through postpartum follow-up. Participants in the mindfulness workshop also demonstrated a trend toward a lower rate of opioid analgesia use in labor.

In a qualitative study, researchers conducted in-depth interviews at four to six months postpartum with ten mothers at increased risk of perinatal stress, anxiety and depression and six fathers who had participated in a Mindfulness Based Childbirth and Parenting Program (MBCP).5 The MBCP program integrates mindfulness training into childbirth education. Participants meet for eight 2 hour and 15 minute weekly sessions and a reunion after babies are born. Specific mindfulness practices introduced include body scan, mindful movement, sitting meditation and walking meditation. Also, methods to integrate mindfulness into pain management, parenting and activities of daily living are introduced. Participants are asked to practice at home for 30 min per day in between sessions supported by audio guided instructions and informative texts.

Participants in the MBCP Program described gaining new skills for coping with stress, anxiety and pain, as well as developing insight and self-compassion and improving communication. Participants attributed these improvements to an increased ability to focus and gain a wider perspective as well as adopt attitudes of curiosity, non-judging and acceptance. In addition, they described mindfulness training to be helpful for coping with childbirth and parenting, including breastfeeding troubles, sleep deprivation and stressful moments with the baby.

These findings demonstrate potential therapeutic outcomes of integrating mindfulness training into childbirth preparation. Although this is a young field and more research is warranted, there is substantial research demonstrating mindfulness training improves stress management, pain management and decreases physiological markers of stress in a wide range of patient populations.6, 7 While the interventions in the above two studies introduce mindfulness in a group format, I have also found that patients can greatly benefit from being taught mindful principles and practices in one-on-one treatment sessions.

Carolyn will share her over-30 years of training and experience teaching mindfulness to patients both individually and in group settings in her course, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, coming up on October 26 and 27 in Houston, TX. Participants will return to the clinic with skills to not only help patients, but to also help themselves be less stressed, more mindful providers!

1. Alehagen S, Wijma K, Wijma B. Fear during labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(4): 315–320.

2. Laursen M, Johansen C, Hedegaard M. Fear of childbirth and risk for birth complications in nulliparous women in the Danish national birth cohort. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009:116(10): 1350–1355.

3. Isgut M, Smith AK, Reimann. The impact of psychological distress during pregnancy on the developing fetus: Biological mechanisms and potential benefits of mindfulness interventions. J Perinat Med. 2017 Dec 20;45(9):999-1011.

4. Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Chao MT. The benefits of preparing for childbirth with mindfulness training: a randomized controlled trial with an active comparison. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017. May 12;17(1):140.

5. Lonnberg G, Nissen E, Niemi M. What is learned from Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting Education? – Participants’ experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18: 466.

6. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):199-213.

7. Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Jenkins ZM, Ski CF. Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:156-78.

I recently found this article from the Psychology Research and Behavior Management Journal. I found myself curious about how other healthcare disciplines treat a diagnosis that often presents in conjunction with pelvic floor dysfunction. Irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, affects nearly 35 million Americans. It is considered a ‘functional’ condition meaning that symptoms occur without structural or biochemical pathology. There is often a stigma with functional diagnosis that the symptoms are “all in their heads”, and while there are many theories about what predisposes individuals to IBS, the experts now think of IBS as a “disorder of gut brain interaction”. Generally, there are 3 subtypes of IBS where people note either constipation dominant, diarrhea dominant or mixed. In order to be diagnosed an individual must report abdominal pain at least 1 day per week in the last 3 months which is related to stooling and a change in frequency or form. Other symptoms that are common are bloating, nausea, incomplete emptying, and urgency.

The author suggests a biopsychosocial framework to help understand IBS. An interdependent relationship between biology (gut microbiota, inflammation, genes), behavior (symptom avoidance, behaviors), cognitive processes (“brain-gut dysregulation, visceral anxiety, coping skills”), and environment (trauma, stress). The brain-gut connection by a variety of nerve pathways is how the brain and gut communicate in either direction; top down or bottom up. Stress and trauma can dysregulate gut function and can contribute to IBS symptoms.

Stress affects the autonomic nervous system that contributes to sympathetic (fight/flight) and parasympathetic (rest/digest). Patients with IBS may have dysfunction with autonomic nervous system regulation. Symptoms of dysregulated gut function can present as visceral hypersensitivity, visceral sensitivity, and visceral anxiety. Visceral hypersensitivity is explained as an upregulation of nerve pathways. The author sites studies that note that IBS patients have a lower pain tolerance to rectal balloon distention than healthy controls. Visceral sensitivity is another sign of upregulation where IBS patients have a greater emotional arousal to visceral stimulation and are less able to downregulate pain. The author notes that the IBS population show particular patterns of anxiety with visceral anxiety and catastrophizing. Visceral anxiety is described hypervigilance to bowel movements and fear avoidance of situational symptoms. For example, fear of not knowing where the bathroom is located.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be an effective treatment to decrease the impact of IBS symptoms. CBT is focused on modifying behaviors and challenging dysfunctional beliefs. CBT can be presented in a variety of ways, however most include techniques consisting of education of how behaviors and physiology interplay for example the gut and stress response; relaxation strategies, usually diaphragmatic breathing and progressive relaxation; cognitive restructuring to help individuals see the relationship between thought patterns and stress responses; problem-solving skills with shift to emotion focused strategies (“acceptance, diaphragmatic breathing, cognitive restructuring, exercise, social support”) instead of problem focused strategies, and finally exposure techniques to help the individual slowly face fear avoidance behaviors. So much of the techniques are similar to what pelvic floor therapists try to educate our patients in. It is reassuring to me that through we may be different disciplines we are on the same team are moving towards the same goal. The author recommends a 10 session treatment duration, and notes that may be a barrier for some. Integrated practice with other healthcare professionals is also recommended. The more we can know about what our other team members are doing to help support patients the more effective we all are.

Kinsinger, Sarah W. “Cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome: current insights” Psychology research and behavior management vol. 10 231-237. 19 Jul. 2017, doi:10.2147/PRBM. S120817

Most clinicians will agree that stress can amplify a patient’s pain and slow recovery. Mindfulness training provides patients with the ability to self-regulate their stress reaction and has been shown to reduce pain and depression and improve quality of life in patients with chronic pain conditions.1 The growing popularity of meditation training to manage stress has led to an increased interest in the physiological mechanisms by which meditation influences the body’s stress reaction. A systematic review and meta-analysis examined the results of randomized controlled trials that compared the impact meditation interventions to active control groups on stress measures. 2 Forty-five studies were included. Meditation practices examined were focused attention, open monitoring and mantra repetition. Outcome measures studied were cortisol, blood pressure, heart rate, lipid and peripheral cytokine expression. Studies had diverse participants including healthy adults, undergraduate students, army soldiers, veterans, cancer survivors, and individuals with chronic pain conditions, cardiovascular disease, depression and hypertension.

When all meditation forms were analyzed together, meditation reduced blood cortisol, C-reactive protein, resting and ambulatory blood pressure, heart rate, triglycerides and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. The effect of meditation on:

When all meditation forms were analyzed together, meditation reduced blood cortisol, C-reactive protein, resting and ambulatory blood pressure, heart rate, triglycerides and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. The effect of meditation on:

- Cortisol and resting heart rate was considered to be high level of evidence.

- C-reactive protein, blood pressure, triglycerides and tumor necrosis factor-alpha was considered to be moderate level of evidence.

Analyzed individually:

- Open monitoring meditation reduced ambulatory systolic blood pressure, systolic blood pressure following a stress test and resting heart rate. Effects assessed as providing moderate level of evidence.

- Focused awareness reduced blood cortisol and resting systolic blood pressure. Effects assessed as providing low level of evidence.

- Mantra repetition reduced systolic blood pressure. Effects assessed as providing low level of evidence.

Authors report the primary reason for downgrading the grade of evidence when analyzing meditation practices individually was the limited number of studies available and small sample sizes. They conclude overall, when compared to an active control (relaxation, exercise or education) meditation practice leads to decreased physiological markers of stress in a range of populations.

Carolyn will offer her popular course, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, in Portland OR, July 27 and 28 and again in Houston TX, October 26 and 27. We recommend these unique opportunities to train with Carolyn, a nationally recognized leader trailblazing the successful applications of mindfulness into pain treatment and the field of physical therapy. Hope to see you there!

1. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):199-213.

2. Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Jenkins ZM, Ski CF. Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:156-78.

Pain demands an answer. Treating persistent pain is a challenge for everyone; providers and patients. Pain neuroscience has changed drastically since I was in physical therapy school. This update comes from the International Spine and Pain Institute headed by the lead author Adriaan Louw, PT, PhD. If you are interested in reading more about persistent pain, I suggest reading the article in its entirety.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

Pain neuroscience education is a way to explain pain to patients, often with analogies, with a focus on neurobiology and neurophysiology as it relates to that individuals pain experience. To be able to educate our patients, we as providers, must be able to understand neuromatrix, output, and threat. Moseley states “[p]ain is a multiple system output activated by an individual’s specific pain neuromatrix. The neuromatrix is activated whenever the brain perceives a threat”. If that sounds like gibberish, consider watching this TEDx talk by Lorimer Moseley on YouTube (the snake bite story is a favorite of mine):

What is a neuromatrix? Essentially, it is a pain map in the brain; a network of neurons spread throughout the brain, none of which deal specifically with pain processing. The way I visualize it is to think about what goes on when you think of your grandmother. There isn’t a grandmother center in the brain, but there are sights and smells (sensory), feelings (emotional awareness), and memories that all come up when you think about her. When we are overwhelmed with pain, those regions become taxed and the individual may have difficulty concentrating, sleeping, and/or may lose his/her temper more easily. Just as each person’s grandmother is different so is a person’s pain and the neuromatrix is affected by past experiences and beliefs.

Pain is an output. It is a response to a threat. When a person is exposed to a threatening situation, biological systems like the sympathetic nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, gastrointestinal system, and motor response system are activated. When a stress response occurs, these systems are either heightened or suppressed to help cope, thanks to the chemicals epinephrine and cortisol.

What is a threat? Threats can take a variety of forms; accidents, falls, diseases, surgeries, emotional trauma, etc. Tissues are influenced by how the individual thinks and feels, in addition to social and environmental factors. The authors propose that when individuals live with chronic pain, their body reacts as though they are under a constant threat. With this constant threat the system reacts and continues to react, and the nervous system is not allowed to return to baseline levels. This can create a patient presentation with immunodeficiency, GI sensitivity, poor motor control, and more. This sounds like most patients who walk into my clinic. The authors suggest that one system may be affected more and that can influence what the patient is diagnosed with even though the underlying biology is the same for many conditions. There are theories for why that happens; genetics, biological memory, or it could be the lens of the provider that the patient sees. There is a table in the article that shows symptoms, diagnosis, and current best evidence treatment for the conditions of fybromyalgia, chronic fatique syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease which is worth a look. The treatments all work to calm the central nervous system.

The authors go on to question the relationship between thyroid function and these conditions as changes in cortisol and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is fascinating, and confusing. Luckily, the Pelvic Floor Series Capstone course does a great job breaking it down.

Now that this hypothetical patient is in our treatment room what do we do? The authors suggest seeing these conditions for what they are: chronic pain conditions. They recommend that physical therapists see past the label that a patient may have picked up with a previous diagnosis, and keep the following in mind when treating these patients:

- They are hurting

- They are tired

- They may have lost hope

- They may be disillusioned by the medical community

- They need help

These people need the following from their medical providers:

- Compassion

- Dignity

- Respect

With empathy and understanding therapists can use skills in education, exercise and movement with the intent to improve system function (immune, neural, and endocrine), rather than fixing isolated mechanical deficits.

Louw, Adriaan PT, PhD; Schmidt, Stephen PT ; Zimney, Kory PT, DPT ; Puentedura, Emilio J. PT, DPT, PhD Treat the Patient, Not the Label: A Pain Neuroscience Update.[Editorial] Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 43(2):89-97, April/June 2019.