As a small business owner, I’m grateful to have weathered the COVID-19 storm. When reflecting on the 5 year anniversary of the shutdown, I remember how we adapted day after day — masking up, running air filtration systems, and feeling grateful that we could continue to do our work safely. Yet, despite prioritizing sleep, nourishing my body with fresh food, staying active, and hydrating well, I sometimes still feel myself carrying a lingering undercurrent of stress and tension in my physical body.

We have spent years holding our breath—both literally and figuratively. The weight of collective uncertainty, change, and grief may have left some imprints on our bodies. I was reminded of this when a sudden flare of lumbopelvic pain forced me to pay closer attention to my own breath patterns. It became clear that I needed to soften, to release layer by layer of held tension, and to deepen my own breathwork and meditation practice.

As healthcare providers, our work extends beyond addressing physical concerns. We are honored to hold space for our patients' grief—whether it stems from physical trauma, medical challenges, gaslighting, or life's hardships.

They trust us, not just for guidance on optimizing their pelvic health, but as guides on their healing journeys. And yet, we too are human. We experience burnout, fatigue, and emotional strain.

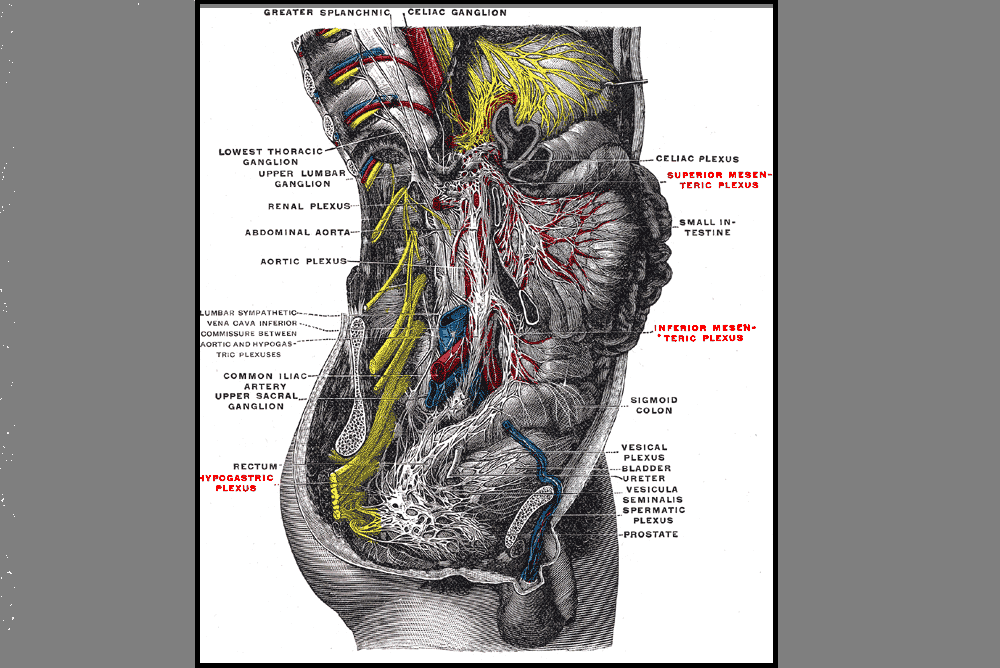

We often teach our patients that breath is a bridge—connecting the nervous system, digestion, spine, pelvic floor, and our emotional state. It is one of the most powerful tools we have to remind the body that it is safe. And yet, even with this knowledge, we may find ourselves unconsciously holding our breath because we are humans living in this unpredictable and sometimes challenging world. When we resist feeling something, we don’t breathe. When we are afraid, we hold tension in our ribs. Even in moments when we think we are relaxed, we can sometimes still be bracing our jaw, back, or pelvic floor.

Let’s take a moment to pause.

Notice your body. Try not to make any adjustments to “fix” your posture.

- Where is your ribcage in relation to your pelvic floor?

- Does the breath feel deep or shallow, smooth, or restricted?

- Where do you sense movement—your chest, ribs, belly?

- What temperature is the air as it enters your nose?

What does it feel like to exhale?

- Does your breath release with ease or feel held back?

- Can you soften just a little more with each out-breath?

- Notice if there is a natural pause before your next inhale—what does that moment of stillness feel like?

If you're sitting, allow yourself to slouch for a moment.

- How does your breath feel in this position?

- Is it shallow or restricted?

- Now, gently imagine your head and spine being drawn upward, as if a magnet is lifting you toward the ceiling. Take another breath. Does it feel different? Notice any shifts in ease of expansion or softening more fully after the exhale.

Now, let’s zoom into the intercostal spaces.

- Imagine this space expanding with each inhale and softening with each exhale.

- Can you soften any more in your ribcage?

- Picture your shoulders softening, warm water is dripping down the upper trap and down the arms.

- Let your jaw unclench, your tongue relax, the space between your eyebrows melt.

Take another long, conscious breath.

- What do you notice?

- Does your body feel a little softer, a little more open, or is there still a place holding tension, waiting for a little more attention?

As practitioners, we give so much to others all day long and sometimes forget to remember to check in with ourselves. Staying connected to our own breath and body serves us just as much as it serves our patients. When we remain grounded and at ease, we can reduce fatigue, physical discomfort, and emotional exhaustion.

So, let’s remind ourselves—throughout the day—to take long easy breaths, soften our jaws, and allow our bodies to move with greater ease. It is not only a gift to ourselves to prevent burn out, but also helps us facilitate co-regulation with our patients’ nervous systems.

If you enjoyed this article, then join Dustienne in her upcoming remote course Yoga for Pelvic Health, on May 3-4, 2025. This two-day remote course offers participants an evidence-based perspective on the value of yoga for patients with chronic pelvic pain and focuses on two of the eight limbs of Patanjali’s eight-fold path: pranayama (breathing) and asana (postures) and how they can be applied for patients who have hip, back and pelvic pain. The course will describe the role of yoga within the medical model, discuss contraindicated postures, and explain how to incorporate yoga home programs as therapeutic exercise and neuromuscular re-education both between visits and after discharge.

AUTHOR BIO

Dustienne Miller PT, MS, WCS, CYT

Dustienne Miller PT, MS, WCS, CYT (she/her) is the creator of the two-day course Yoga for Pelvic Pain and an instructor for Pelvic Function Level 1. Born out of an interest in creating yoga home programs for her patients, she developed a pelvic health yoga video series called Your Pace Yoga in 2012. She is a contributing author in two books about the integration of pelvic health and yoga, Yoga Mama: The Practitioner’s Guide to Prenatal Yoga (Shambhala Publications, 2016) and Healing in Urology (World Scientific). Prior conference and workshop engagements include APTA's CSM, International Pelvic Pain Society, Woman on Fire, Wound Ostomy and Continence Society, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Annual Assembly.

Her clinical practice, Flourish Physical Therapy, is located in Boston's Back Bay. She is a board-certified women's health clinical specialist recognized by the American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties. Dustienne weaves yoga, mindfulness, and breathwork into her clinical practice, having received her yoga teacher certification through the Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health in 2005.

Dustienne's love of movement carried over into her physical therapy and yoga practice, stemming from her previous career as a professional dancer. She danced professionally in New York City for several years, most notably with the national tour of Fosse. She bridged her dance and physical therapy backgrounds working for Physioarts, who contracted her to work backstage at various Broadway shows and for the Radio City Christmas Spectacular. She is currently an assistant professor of jazz dance at Boston Conservatory at Berklee.

Dustienne passionately believes in the integration of physical therapy and yoga within a holistic model of care. Her course aims to provide therapists and patients with an additional resource centered on supporting the nervous system and enhancing patient self-efficacy.

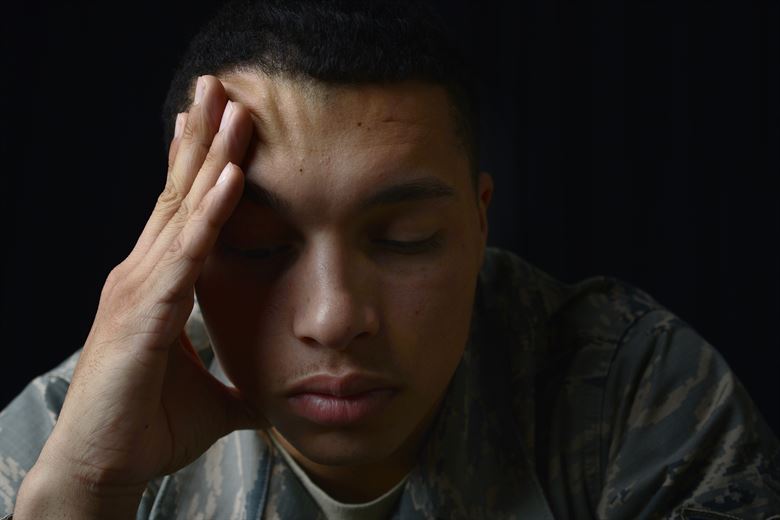

When I mentioned to a patient I was writing a blog on yoga for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), she poured out her story to me. Her ex-husband had been abusive, first verbally and emotionally, and then came the day he shook her. Violently. She considered taking her own life in the dark days that followed. Yoga, particularly the meditation aspect, as well as other counseling, brought her to a better place over time. Decades later, she is happily married and has practiced yoga faithfully ever since. Sometimes a therapy’s anecdotal evidence is so powerful academic research is merely icing on the cake.

This study by Walker and Pacik (2017) included 3 voluntary participants: a 75 and a 72 year old male veteran and a 57 year old female veteran, all whom were experiencing a varying cluster of PTSD symptoms for longer than 6 months. Pre- and post-course scores were evaluated from the PTSD Checklist (a 20-item self-reported checklist), the Military Version (PCL-M). All the participants reported decreased symptoms of PTSD after the 5 day training course. The PCL-M scores were reduced in all 3 participants, particularly in the avoidance and increased arousal categories. Even the participant with the most severe symptoms showed impressive improvement. These authors concluded Sudarshan Kriya (SKY) seemed to decrease the symptoms of PTSD in 3 military veterans.

Cushing et al., (2018) recently published online a study testing the impact of yoga on post-9/11 veterans diagnosed with PTSD. The participants were >18 years old and scored at least 30 on the PTSD Checklist-Military version (PCL-M). They participated in weekly 60-minute yoga sessions for 6 weeks including Vinyasa-style yoga and a trauma-sensitive, military-culture based approach taught by a yoga instructor and post-9/11 veteran. Pre- and post-intervention scores were obtained by 18 veterans. Their PTSD symptoms decreased, and statistical and clinical improvements in the PCL-M scores were noted. They also had improved mindfulness scores and decreased insomnia, depression, and anxiety. The authors concluded a trauma-sensitive yoga intervention may be effective for veterans with PTSD symptoms.

Domestic violence, sexual assault, and unimaginable military experiences can all result in PTSD. People in our profession and even more likely, the patients we treat, may live with these horrors in the deepest recesses of their minds. Yoga is gaining acceptance as an adjunctive therapy to improving the symptoms of PTSD. The Trauma Awareness for the Physical Therapist course may assist in shedding light on a dark subject.

Walker, J., & Pacik, D. (2017). Controlled Rhythmic Yogic Breathing as Complementary Treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Military Veterans: A Case Series. Medical Acupuncture, 29(4), 232–238.

Cushing, RE, Braun, KL, Alden C-Iayt, SW, Katz ,AR. (2018). Military-Tailored Yoga for Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Military Medicine. doi:org/10.1093/milmed/usx071

Examples of pranayama

Ujjayi

Letting Go Breath

Integrating into the clinic

1) Iyengar BKS. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Schocken; 1995.

2) Sapsford RR, Richardson CA, Maher CF, Hodges PW. Pelvic floor muscle activity in different sitting postures in continent and incontinent women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(9):1741-1747.15.

3) Julie Wiebe, Physical Therapist | Educator, Advocate, Clinician. 2015; http://www.juliewiebept.

4) Talasz H, Kremser C, Kofler M, Kalchschmid E, Lechleitner M, Rudisch A. Phase-locked parallel movement of diaphragm and pelvic floor during breathing and coughing-a dynamic MRI investigation in healthy females. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(1):61-68.

5) Sapsford R. Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Man Ther. 2004;9(1):3-12.

6) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

7) Massery M. THE LINDA CRANE MEMORIAL LECTURE: The Patient Puzzle: Piecing it Together. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2009;20(2):19-27.

8) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.