The first round of certification candidates have completed their testing, and we will soon announce the test takers who will be awarded with the letters "PRPC" for Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification. Just over 70 candidates sat for the exam during our inaugural 2014 testing window, and are now eagerly awaiting their results (we thank them for their patience!)

Each step of this vigorous (and often tedious) process has been guided by Kryterion, a company who specializes in certification development. We want to give you an update about where we are in the process as many are interested in finding out how they performed on the test.

The "cut score" for passing the exam and earning the certification can only be determined after all the examinees have completed the exam, so we could not begin our work until the testing window closed on March 1st. Then, a group of 11-14 SME's (Subject Matter Experts) are gathered together on phone and web conferences to review each item. A SME is a person who meets the criteria to take the PRPC exam but cannot be someone who took the exam this year. Many of the SME's are therapists who have been involved in the process from the beginning, others have joined the group specifically for this last step, the review process.

Prior to the phone and web conferences, the each SME completes a training in rating the difficulty of items. She then independently rates every single item based on this thought: "what percentage of minimally acceptable candidates would get this item correct?" The criteria for a minimally acceptable candidate was determined in the exam development process and constitutes what a therapist should know or be able to do at a minimum to earn the credential. During our review phone calls the SMEs are all presented with the given ratings for each item, discuss the ratings as needed, and then an average rating for each item is created. At this time, we have completed over 4 hours of conferences together and have approximately 3-4 hours more to complete. As the SMEs live across the United States (and across several time zones), work full time jobs, attend school, and are raising families, this process is quite a challenge to coordinate and a sacrifice on the part of the SME.

Despite the hard work and sacrifices, the subject matter experts are committed to finalizing the cut score process within the next couple weeks. Once this is completed the cut score is determined based on the review and rating process, and we will be able to present therapists whose exam scores meet or exceed the cut score with their new designation. Participants who meet the criteria and earn a score at or above the cut score will be notified by email of their status. If you are currently awaiting notification of PRPC status, please be patient; we are very close to having the information that we need to finalize this rigorous process. We will also announce on our Facebook page and in a newsletter once we have completed the rating process, so stay in touch with us and watch your email.

If you are considering applying for the PRPC exam, all the information that you need to know can be found here. The next opportunity to sit for the exam happens in November of 2014. Thank you to everyone who has been a part of the process, from the administrative to the clinical to the test taking side! The PRPC exam is the only certification currently available that recognizes expertise in pelvic rehabilitation, a distinction that will serve to set a therapist apart and acknowledge all of the hard work that he/she has completed.

This post was written by H&W faculty member Teri Elliott-Burke, PT, MHS, BCB-PMD. Teri will be teaching Pelvic Floor Level 2A in Maywood, IL next month.

A new product has hit the stores – Butterfly Body Liners. These pads are specifically designed to deal with fecal incontinence (aka ABL – Accidental Bowel Leakage). The good news is that advertisements for these pads bring fecal incontinence out in the open. The ads promote discussion of this topic and offer one solution for this condition. A patient first brought this product to my attention. So I thought it would be a good idea for all of you to know about them as well (as I have discussed the concept of the pad with other patients they have liked the idea). However, I would also like to voice two concerns: One is that the pads seem pricey ($.30 each) especially for patients who have to change them often or are on a fixed income. My second reaction is that for some people these small pads don’t have enough capacity to deal with the problem.

I am grateful for the development of pads for this condition, however I find myself frustrated with this advertisement, as well as advertisements for urinary incontinence pads. I find myself wanting to strangle celebrities touting the use of pads (notice so far none of them are willing to own up to fecal incontinence). The pads, which are a necessity for some, offer only a passive solution. The fact that this condition can be accurately diagnosed and treated is never mentioned. Of course, mentioning an active solution doesn’t sell the products. Therefore, we need to be the voices out there letting people know there is an active solution to this issue. This includes marketing to physicians to let them know of the treatment we can provide.

Another “product” related to fecal incontinence is the newly developed Fecal Incontinence and Constipation Questionnaire. (Check out the February 2004 Physical Therapy Journal (PTJ) article that addressed the formation of this questionnaire). This is an exciting development in the area of outcomes questionnaires to address the specific patient population of fecal incontinence and constipation. Although there are other questionnaires available this one was developed specifically for patients seeking put patient rehabilitation services for pelvic-floor dysfunction. This questionnaire has two subscales Fecal Incontinence (FI) and Fecal Constipation (FC). Analysis showed sound psychometric properties of this scale, although further fecal constipation items were recommended to increase content coverage. Reminder: For those of you how are APTA members the PTJ has a app.

If you are treating patients with urinary incontinence, but are not adequately addressing fecal incontinence or constipation you are missing out on giving relief to many people. Make your way to PF2A where issues of constipation and fecal incontinence are addressed.

This post was written by H&W instructor Dee Hartmann PT, DPT. This year, H&W is thrilled to be offering a brand new coure instructed by Dee, Assessing and Treating Women with Vulvodynia.This course will be offered in September in Waterford, CT.

What's love (and sex) got to do, got to do with it?

Tina Turner said it well. (Obviously I’m taking a little liberty here.) Some think that love and sex go together, you know, like bread and butter. Others? Not so much. Many think that love thrives even though the sex may slow down because of things like babies, work, stress, dinner with friends, and cleaning the bathroom…you name it. A lot can come between you and a good bedroom romp. But what if those bedroom romps had NEVER been good? What if the only fireworks you remember when earning your womanhood badge were akin to hot, searing sparklers—held way too close for comfort above your knees and between your legs. What’s with that, right?

Tina goes on “…that the touch of your hand/makes my pulse react…”. We all remember that feeling, that first titillation. It was there “…It’s physical/Only logical/You must try to ignore/That it means more than that”.

Boy meets girl. Hugging. Touching. Kissing. All that normal stuff that’s so good. Further progression might be awkward and clumsy but ‘it’ usually works nonetheless. But not always. Sometimes, the sex afterglow is more like, “Wow. That was way overrated…and who lit the fire in my vagina?” That burning pain lingers for days and celibacy, though considered, doesn’t really seem like a good alternative. You try again and again and along with more failed attempts, the pain gets worse. Your brain begins to think that any time anything comes too close to your vagina – like a tampon, fingers, a vibrator, the doctor, or a bicycle seat – it needs to shut the doors for business. As we say in the business, the pelvic floor muscles go into overdrive. Everything can get a bit goofy. You become all too familiar with your work bathroom as your bladder doesn’t seem to want to hold as much as it used to. Emptying your bowels becomes an effort. And those tampons that wouldn’t go in? Now you know why. There’s no room for anything down there! Armed with the sparkler analogy, the only help you get from most medical providers is “just relax, honey” or “have a glass of wine first” or “maybe your boyfriend/husband is just too big for you.” That stinks. And it’s not normal. Sex and reproduction (remember we’re the only mammals—besides dolphins—who do it for fun) are built in to our primitive brain, just like breathing and eating. “It may seem to you/That I'm acting confused/When you're close to me/If I tend to look dazed.” After the whole relaxing and drinking things fail and you kind of like your partner’s parts, what’s a girl to do?

“I've been taking on a new direction/But I have to say/I've been thinking about my own protection/It scares me to feel this way.” Once pain and fear have taken the place of excitement and arousal, your sexual future may appear less and less clear. As you and your partner begin experiencing nothing but frustration, there are my tips for making it through this tough stage.

1) Your best tool is always communication, communication, communication. First and foremost, sex should never hurt. Never. Ever. Discuss it with your partner long before you’re in bed, the lights are out, and you’re pretending to be asleep to dodge foreplay. Desire and arousal go together to create increased blood flow and lubrication, but no one can deny that it’s pretty hard to get excited about a hot stick in the eye (my analogy). Fear of impending pain can throw a wet blanket on the whole idea of sex unless you’ve agreed first to work together.

2) You may have learned to fear touching because of where it might lead, but avoiding hugging, touching, cuddling, and kissing is the first step in the wrong direction. Enjoying your partner’s touch—sexual or not—is a prerequisite for good love-making and will make you both happier in the long run.

3) Make a deal that there will be no sexual contact until you’re ready and will help you to begin dealing with the pain. Keeping your love alive matters for your relationship. Holding back in resentment and fear of the next sexual move chips away at the trust you’ve built.

4) As you begin to regain control, try to be the intimacy initiator at least once a week (or some predetermined time frame). Getting yourself mentally prepared goes a long way to gently urge arousal. Often it takes putting a sticky note on the fridge or work computer screen to remind you to think about it during the day (we women have so many other more important things to think about; sex, even in the best of times, usually doesn’t make the top five). Partners love it as they’ve usually shut down their advances to avoid yet more frustration, rejection, and heartache.

5) Once you’re ready to go for it, remember that your body that might not be too excited about entertaining an extended stay visitor. By agreeing to short visits in the beginning, the brain catches on and doesn’t shut down into protection mode. Go for more foreplay rather than less. Then, once his climax is close at hand, actual penetration time is kept at a minimum. You’ll be happier. He’ll be happier. And your vulva will appreciate the plan.

And here’s where Tina and I part ways. She may have gotten to go on singing (and making millions), but I get to gently guide women to their desired sexuality. Incredible women fill my office every day and continue to amaze me with what they’re able to do with and for their bodies. I don’t fix anyone. Instead, I help them find the power they need to fix themselves. “What's love got to do, got to do with it/What's love but a sweet old fashioned notion.” Call me old fashioned but I can’t think of a greater gift as women’s health PTs than to be able to help women feel more comfortable as women. And to think they call this work!

Want more from Dee? Consider joining us for the Septmber course!

Research completed by medical faculty of Heidelberg University in Germany aimed to better understand the characteristics of pain that can be caused by different structures or tissues within the low back. Is the information gained applicable to all layers of tissues in the body? If so, how does that assist with our structural evaluation and interventions? If not, how do various body regions reflect the findings of this study?

Researchers injected saline into tissues of the back of 12 healthy subjects at differing layers of depth and tissue; the injections were guided by ultrasound. (This method of inducing muscle pain has been utilized and refined since the 1930's.) The authors describe prior studies indicating that thoracolumbar fascia is innervated by free nerve endings, and that lumbar dorsal horn neurons receive nociceptive input from fascia; these connections are theorized to relate to fascia as a potential cause of low back pain.

The volunteer subjects were both male (6) and female (6) and none had a history of back pain. 3 sessions were scheduled with at least 5 days between study sessions. Following saline injection, the subjects rated pain at 10 second intervals for two minutes, then at 30 second intervals for the next 23 minutes. Subjects also recorded on a body chart where the symptoms occurred. Pressure pain threshold was recorded using a pressure algometer at baseline and at 25 minutes post-injection. Pain quality was assessed with an outcomes tool that listed both affective and sensory items.

The authors conclude that, in response to saline injection, the thoracolumbar fascia is more sensitive to the chemical irritation than the erector spine muscles or the overlying cutis (the dermis and epidermis, or combined layers of the skin.) Areas of recorded pain were larger for fascial injection than for skin or muscle. However, hyperalgesia to blunt pressure as measured by the pressure pain threshold device could only be created by injections into the muscle. In summary, the article states that injection to the thoracolumbar fascia "…induces intense tonic pain with a strong affective component and a pain radiation similar to acute LBP," whereas hyperalgesia to pressure "…seems to require peripheral sensitization of muscle nociceptors."

Does this research offer a window into the symptomatology and etiology of varying pain complaints? Can we direct our treatment to the tissues that appear to be at fault? The more we know about the tissues of the body, how to differentiate structurally the ways in which pathologies present, perhaps we will continue to build our clinical reasoning upon the anatomy and pathological findings. For more research and clinical applications surrounding fascia, you still have time to sign up for faculty member Ramona Horton's courses on myofascial evaluation and interventions for pelvic dsyfunction.

What is a hymenectomy, and how does it relate to pelvic rehabilitation? To answer this question, an understanding of hymenal anatomy is useful. The hymen is tissue that lines and sometimes covers the vaginal opening. This layer of tissue can be thick or thin, and can have a variety of presentations based on embryological development such as micro perforations, bands, or septa which create distinct openings into the vaginal canal. During menstruation, having an opening through the hymen is critical so that menstrual discharge does not become blocked, and sexual function is optimized when the hymen does not create any narrowing or blockage. When the hymen completely covers the vaginal opening the condition is known as "imperforate hymen." Sometimes this anatomical variation is noticed during neonatal and early childhood examinations, unfortunately, the condition may also be undiagnosed.

Prior to her first gynecological examination, an adolescent female may be at risk for consequences of an imperforate hymen. Depending on the hymenal variation, a young female may experience urinary dysfunction or vaginal infection, but more typical is recognition of the issue when her menstrual cycle begins. Case reports in the literature describe the condition as presenting clinically as low back pain, or as abdominal pain.Complaints that may increase our suspicion about the condition in an adolescent patient may include amenorrhea, abdominal mass, abdominal pain, urinary retention, or constipation.

While it may be uncommon for us to encounter an adolescent with back or pelvic pain who has not been screened by a medical provider, knowing about the condition adds to our toolbox for medical screening. We may also meet patients who are referred to the clinic following a hymenectomy, a surgical procedure that removes all or part of a woman's hymen. In asymptomatic patients who have an imperforate hymen, a surgical procedure may be delayed until puberty, when estrogen's effects on the tissues may negate the need for a procedure. Click here to view basic images of the procedure, and here to access a Medscape article with further details about epidemiology, pathophysiology, and relevant anatomy.

Unfortunately, we know that patients frequently lack a referral for conservative care for pelvic pain or dysfunction that may arise from hymenal dysfunction or surgeries. One of my most memorable and endearing patients told me her horrifying memory of having a hymenal procedure as a young child without any anesthesia.Is that the reason that she developed severe pelvic muscle dysfunction in adulthood? While we can only speculate about this connection, the more we know about a patient's history and how the reported complaints may link to dysfunction, the better. If you would like to know more about hymenectomies and other special topics, come to California, Illinois, or Connecticut this year for one of our PF3 courses to hear from experts Holly Herman and Lila Abbate.

This post was written by H&W instructor Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, BCB-PMD. Allison will be instructing the Rehabilitative Ultrasound course in Seatlte in May.

In the past decades, evidence has been established showing the importance of the local stabilizing muscles, including the transverse abdominis, the lumbar multifidus, and the pelvic floor muscles on the stability of the pelvic ring and lumbar spine. Many therapists have embraced this knowledge and incorporate a specific stabilization program into their plan of care for patients with dysfunction in the lumbar spine or pelvic ring. This plan of care can be more time consuming for the therapist since we are no longer simply prescribing strengthening exercises to the patient, but instead are using neuromuscular re-education to retrain recruitment patterns and improve motor control. For many patients, learning to activate these muscles can be very difficult and frustrating. This is where biofeedback comes in. For years, women’s health therapists have been using biofeedback to retrain the pelvic floor muscles. Biofeedback is the process of bringing unconscious physiological processes to consciousness and gaining control over it. These same principles can be used in retraining the lumbar multifidus and the transverse abdominis, in addition to the pelvic floor. Currently, biofeedback methods used in treating low back pain include rehabilitative ultrasound imaging (RUSI) and the pressure cuff. My preferred method is using RUSI. This tool not only provides biofeedback for the patient but allows for real-time assessment of the muscle activation. Thus, providing the clinician valuable feedback on timing of recruitment and strategy used by the patient that would not be assessed with palpation alone.

Giggins et al recently released a literature review that covered different forms of biofeedback used in rehabilitation. Interestingly, there is little evidence to support the use of pressure cuff. Some of the research reported found significant increases in gluteus medius and internal oblique activity. In 2013, Grooms et al also determined that correlation and likelihood coefficients indicate that the pressure cuff is likely of minimal value to detect transverse abdominis activation. I personally have had patients referred to me from other therapists to confirm whether or not they were activating their transverse abdominis. In previous treatments, the patients had been using the pressure cuff and palpation by the therapist as confirmation of proper activation. What I found was consistently the patients were not achieving good contractions in their transverse abdominis muscles. Most of these patients were able to learn in one or two sessions how to properly contract their transverse abdominis, and were later able to progress to performing a co-contraction of all the local stabilizers during motor tasks.

Hides et al published a study that demonstrated a specific stabilization rehabilitation program using RUSI was successful in decreasing pain, increasing muscle cross sectional area, and improving motor control in elite cricket players that had previously experienced low back pain. This is a great example of how neuromuscular re-education using RUSI works for the patient when the therapist is using it as both an assessment tool, as well as a biofeedback tool.

So far the limiting drawback of RUSI is the cost of the ultrasound unit. However, companies are constantly coming out with more affordable units making this useful tool more available for clinics. If you are interested in learning more about using US imaging as both an assessment and biofeedback tool join me in Seattle this May for a course that addresses the use of Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging in conjunction with a specific stabilization program.

References:

Giggins, Persson, Caulfield. Biofeedback in Rehabilitation. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation.2013; 10:60.

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1743-0003-10-60.pdf

Grooms, Grindstaff, Croy et al. Clinimetric Analysis of Pressure Biofeedback and Transversus Abdominis Function in Individuals With Stabilization Classification Low Back Pain. JOSPT.2013; 43(3):184-193

http://www.jospt.org/doi/abs/10.2519/jospt.2013.4397

Hides, Stanton, Wilson et al. Retraining motor control of abdominal muscles among elite cricketers with low back pain. Scand J Med Sci Sports.2010; 20: 834-842.

Do women who have pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy have altered gait patterns? The answer to this question was the aim of a study published in the European Spine Journal in 2008 by Wu and colleagues. Pelvic girdle pain, defined by Vleeming and colleagues as "…a specific form of low back pain (LBP) that can occur separately or in conjunction with LBP…" has been estimated to occur as often as 50% in pregnancy. (Gutke et al., 2006) Unfortunately, of the women who develop pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy, research has demonstrated that 1 in 4 women will develop chronic postpartum pain. (Ostgaard et al., 1991) Pelvic girdle pain can appear as mild, moderate, or severely debilitating, and can be confirmed using provocation tests such as the posterior pelvic provocation test and the active straight leg raise (ASLR). Our role as pelvic rehabilitation providers is critical in minimizing the functional impact of pelvic girdle pain during and following pregnancy.

In regards to gait changes in women who present with PGP in pregnancy, in general, walking velocity is reduced, is negatively correlated with fear of movement, and there are changes in thorax and pelvic rotations. In the study by Wu and colleagues, kinematics were examined in 11 women with PGP and 12 pelvic-healthy controls. Findings within the patients with PGP include that transverse segmental rotation amplitudes were larger, and peak thorax rotation occurred earlier in the stride cycle at higher velocities. The authors suggest that this change in thorax rotation may aid in avoiding excessive spinal rotations caused by larger segmental rotations, or in limiting the motion in the lumbopelvic region.. They further describe that in healthy subjects, pelvic rotations are relatively out-of-phase with the lower extremities at lower velocities, and more in-phase during higher velocities, and that this pattern may be altered in the presence of PGP.

What is the clinical relevance of this information? The primary author in the study also reported on postpartum pelvic girdle pain and gait, and found that changes in trunk and pelvic coordination persist in the postpartum period, and that an individual may employ a variety of adaptive strategies to deal with pain and possibly weakness during gait. What changes in movement strategies does a patient present with in early postpartum versus late postpartum? Does a woman, if she has never been offered rehabilitation, spontaneously recover from these gait adaptations? How does fear of movement and pain-avoiding strategies affect her movement even decades later? In the absence of having gait laboratories, clinical observation of walking at varied speeds can identify patterns of movement that may be aggravating a spinal or pelvic condition. Does she rotate her trunk with a reciprocal limb pattern? Does she limit rotation at the pelvis and overcompensate in the thoracic spine? Observation of patterns that fit clinical symptoms may assist in avoiding persisting gait alterations. Early recognition of pelvic girdle dysfunction in pregnancy and throughout the postpartum period may allow her to avoid compensations in gait that contribute to musculoskeletal dysfunction. To learn about more exciting concepts in postpartum recovery, come to the Care of the Postpartum Patient in Houston in June or in Chicago area in September!

References

Gutke, A., Östgaard, H. C., & Öberg, B. (2006). Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in pregnancy: a cohort study of the consequences in terms of health and functioning. Spine, 31(5 E149-E155.

Ostgaard, H. C., Anderson, G. B. J., & Karlson, K. (1991). Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy: A review. Spine, 16(5 549-552.

Vleeming, A., Albert, H. B., Östgaard, H. C., Sturesson, B., & Stuge, B. (2008). European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal, 17(6 794-819.

This post was written by guest-blogger, H&W faculty member Michelle Lyons, PT, MISCP, who will be teaching her brand-new course, The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor, in Columbus,OH in August..

‘I approached my advisor and told him that for my PhD thesis I wanted to study the pelvis." He replied ‘That will be the shortest thesis ever…there are three bones and some ligaments. You will be done by next week.’ I told him ‘I think there is more to it’. (Andry Vleeming Phd 2002)

In sports medicine, the primary source of specialist consultation is the orthopaedic surgeon, who may perform a wide ranging assessment of the musculo-skeletal system with no real evaluation of the pelvic girdle or pelvic floor musculature. The patient is unlikely to be asked about urinary, bowel or sexual dysfunction and often does not volunteer this information unless prompted (Jones et al 2013)

The patient will more than likely then be referred to physical therapy but again, unless we as therapists have the knowledge to combine our orthopaedic, sports medicine and pelvic rehab skillsets, we may not be meeting the needs of our athletic patients.

In my new course for Herman & Wallace, The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor, I will be looking at how specific hip and groin injuries can impact the pelvic girdle and pelvic floor. We know that the most common site of strain is the musculo-tendinous junction of the adductor longus or gracilis muscle, and this is also the most common cause of groin pain in the athlete (Reid 1992). In cases where the athlete recalls a specific traumatic event, the diagnosis is more straightforward, but care must be taken to differentiate between muscle strains and tendonoses/ tendonitis from osteitis pubis, sports hernias and nerve entrapment, which can present with similar symptoms, especially if the athlete presents with insidious onset.

We will investigate differential diagnoses including acetabular tears, a recently recognised source of anterior hip, groin and pelvic pain (Lewis and Sahrmann 2006). Studies have indicated that 22% of athletes with groin pain (Narvani et al 2003) and 55% of patients with mechanical hip pain of unknown aetiology (McCarthy et al 2001) have a labral tear. Athletic pubalgias or sports hernias, are another controversial diagnosis. Although more commonly seen in men, but the female proportion, age, number of sports and soft tissue structures involved have all increased recently (Meyers et al 2008) We will also take into account nerve compressions and look specifically at cycling and genito-urinary symptoms in men and women, the potential mechanisms involved and how we as pelvic therapists can intervene.

It will be an intense two days in Ohio this August as we look at integrating the best of current practices in sports medicine with pelvic assessment and rehabilitation – I hope to see you there!

References:

Reid, D.C. (1992) Sports Injury Assessment and Rehabilitation. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Lewis, C.L. & Sahrmann (2006) Acetabular labral tears. Physical Therapy 86 (1), 110-121 Narvani et al (2003) Prevalence of acetabular labral tears in sports patients with groin pain Knee surgery, Sports Traumatology & Arthroscopy 11 (6) 403-408

Meyers et al (2008) Experience with sports hernias spanning two decades Annals of Surgery 248 (4)

This post was written by H&W faculty member Peter Philip, who developed a course on chronic pelvic pain and differential diagnosis for the Institute.

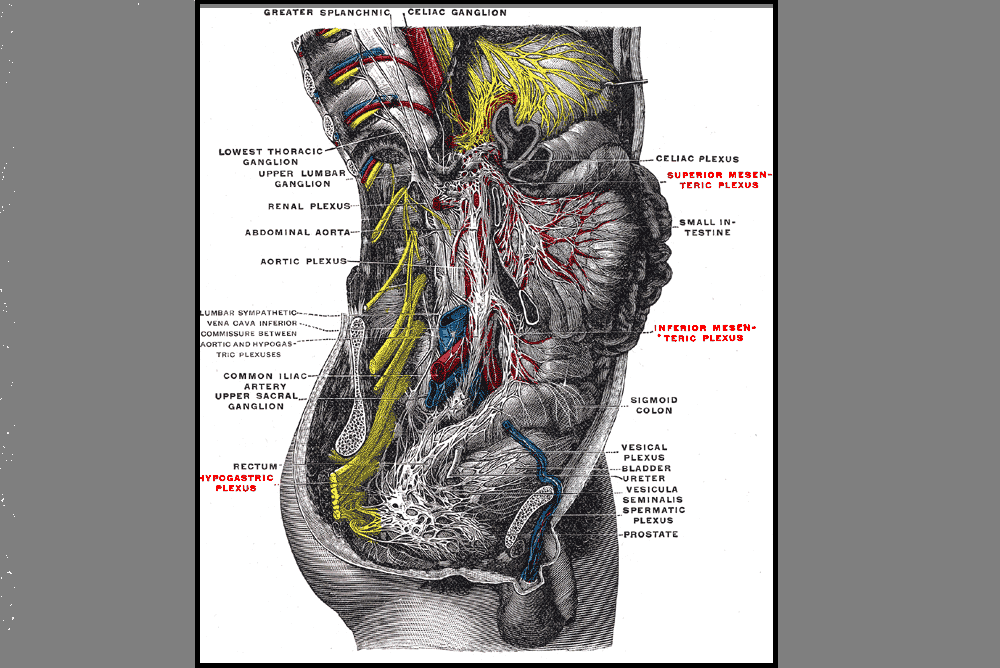

The gut "has a mind of its own." The nervous system within the gut, also called the enteric nervous system (ENS), is located within the sheaths of tissue lining the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and colon. This network consists of neurons, neurotransmitters and proteins that have the distinct capacity to function quite independently. The system can also learn and remember; the joys and sadness that one experiences throughout the day are often reflected within the functional integrity of the enteric nervous system.

Anatomically, the enteric nervous system is connected to the central nervous system via the vagus nerve. “Command neurons” from the brain communicate with the interneurons of the enteric nervous system via the myenteric and the submucosal plexuses. These command neurons together with the vagus nerve, monitor and control the activity of the gut. The ENS is responsible for motility, for ion transport, gastrointestinal (GI) blood flow, and is associated with secretion and absorption. Sensors for sugar, protein, and acidity are a few of the ways that the contents of the gut are monitored within the system.

The enteric nervous system contains 100 million neurons- more neurons than in the spinal cord! Neuropeptides and other neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, glutamate, norepinephrine and nitric oxide are located within the enteric nervous system. During stressful situations, stress hormones are released in the stereotypical fight-or-flight response, which in turn stimulate the sensory nerves of the ENS, leading to what is experienced as the “butterflies”. Fear also amplifies the release of serotonin leading to a hyperstimulation and resulting in diarrhea. The common experience of “choking under stress” can occur due to stimulation of the esophageal nerves.

Medications and drugs will often have unforeseen consequences on the enteric nervous system, and this is an important fact to consider in patient care. Drugs such as Prozac act by preventing serotonin uptake, which leaves the neurotransmitter at abundant levels in the central nervous system (CNS.) In small concentrations, this effect can cause a hastening of gut motility, and in greater concentrations, motility can be paradoxically retarded. Antibiotics can also impact the receptors of the ENS and produce oscillations, creating symptoms of cramping and nausea. The ENS is responding to stress by increasing secretions of histamines, prostaglandin, and other pro-inflammatory mediators. The purpose is protective in nature, because the brain is preparing the GI for mechanical insult, yet the unfortunate secondary effect is also that of diarrhea and cramping.

Fully understanding the neural integration of the ENS with the CNS, and where along the spinal column afferent information terminates is helpful in understanding our patients who suffer with pelvic and digestive pain. Through the integration and understanding of embryogenesis, the clinician will have a more clear understanding of how and where to apply treatments for optimal pain reduction and restoration of function. During the course, Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Pelvic Pain, the participants will learn about the enteric nervous system's relationship to the central nervous system, and much more!

What happens to pelvic floor muscle activation in women who have prolapse and a pessary in place? Kari Bo, an extraordinary contributor to the field of pelvic health, and colleagues in Norway investigated this question. Twenty two women (who acted as their own controls) were measured for vaginal resting pressure and maximal voluntary pelvic muscle contraction with and without a ring pessary in place.The aim of the investigation was to determine if the pelvic floor muscles could improve in activation if the prolapse was repositioned. (The authors take the reader through prior research examples to build this clinical question and theory.) Conclusions of this research indicate that having a pessary in place improved the vaginal resting pressure (VRP) but did not create a statistically significant difference in maximal voluntary contraction (MVC).

For this study, 22 women with grade II-IV prolapse (according to POP-Q) who were able to demonstrate a voluntary pelvic muscle contraction were included. Excluded were women who could not tolerate a ring pessary, those who were breastfeeding or pregnant, women with neurological or musculoskeletal disease that could interfere with ability to contract, and cases in which the prolapse was so severe that measurement with the catheter was prohibited. Maximal contractions and an endurance contraction were measured in supine. No significant difference was noted in MVC or in endurance. A higher vaginal resting pressure, however, was recorded. The authors discuss several theories to explain the increase in resting pressure, but do not provide a conclusion as to the reason for this change. Is there a length change in puborectalis that optimizes the length/tension curve, for example?

Childbirth is one of the leading causes of supportive changes in the pelvic floor, yet women have varied levels of prolapse, and not all prolapses create symptoms or functional limitations. Experienced pelvic rehabilitation therapists will likely concur that there are patients who present with a seemingly severe level of prolapse who have minimal symptoms, and vice versa. While degree of prolapse and levator plate descent has been shown to improve in response to pelvic muscle rehabilitation, women also have reported improved symptoms in the absence of significant objective changes to the level of prolapse. One clinical message that this study adds to the literature is the conclusion that a therapist may not need to have a patient remove her pessary in order to accurately test the muscles. Keeping in mind that the patients were tested in a supine position, there may be clinical relevance for assessing a patient in other positions with and without a pessary in place.

If you enjoy "nerding out" and discussing the potential clinical implications that this type of clinical research provides, you can find more discussions about pessaries in our Pelvic Floor 2B course, next happening in Chicago area in July. This course will sell out, so get your seats soon!

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./