Male Phimosis: Not a Fraction of Retraction

As I read about male phimosis, I thought about a shirt that just won’t go over my son’s big noggin. I tug and pull, and he screams as his blond locks stick up from static electricity. Ultimately, if I want this shirt to be worn, I either have to cut it or provide a prolonged stretch to the material, or my child will suffocate in a polyester sheath. This is remotely similar to the male with physiological phimosis.

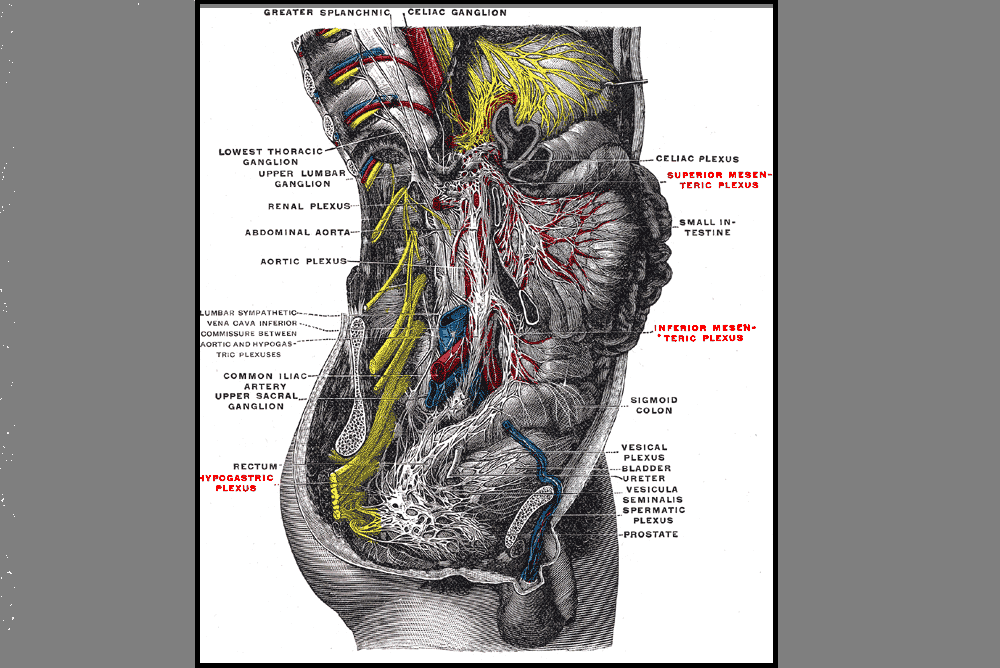

In a review article, Chan and Wong (2016) described urological problems among children, including phimosis. They reported “physiological phimosis” is when the prepuce cannot be retracted because of a natural adhesion to the glans. Almost all normal male babies are born with a foreskin that does not retract, and it becomes retractable in 90% of boys once they are 3 years old. A biological process occurs, and the prepuce becomes retractable. In “pathological phimosis” or balanitis xerotica obliterans, the prepuce, glans, and sometimes even the urethra experience a progressive inflammatory condition involving inflammation of the glans penis, an unusually dry lesion, and occasional endarteritis. Etiology is unknown, but males by their 15th birthday report a 0.6% incidence, and the clinical characteristics include a white tip of the foreskin with a ring of hard tissue, white patches covering the glans, sclerotic changes around the meatus, meatal stenosis, and sometimes urethral narrowing and urine retention.

In a review article, Chan and Wong (2016) described urological problems among children, including phimosis. They reported “physiological phimosis” is when the prepuce cannot be retracted because of a natural adhesion to the glans. Almost all normal male babies are born with a foreskin that does not retract, and it becomes retractable in 90% of boys once they are 3 years old. A biological process occurs, and the prepuce becomes retractable. In “pathological phimosis” or balanitis xerotica obliterans, the prepuce, glans, and sometimes even the urethra experience a progressive inflammatory condition involving inflammation of the glans penis, an unusually dry lesion, and occasional endarteritis. Etiology is unknown, but males by their 15th birthday report a 0.6% incidence, and the clinical characteristics include a white tip of the foreskin with a ring of hard tissue, white patches covering the glans, sclerotic changes around the meatus, meatal stenosis, and sometimes urethral narrowing and urine retention.

This review article continues to discuss the appropriate treatment for phimosis (Chan & Wong 2016). Once phimosis is diagnosed, the parents of the young male need to be educated on keeping the prepuce clean. This involves retracting the prepuce gently and rinsing it with warm water daily to prevent infection. Parents are warned against forcibly retracting the prepuce. A study has shown complete resolution of the phimosis occurred in 76% of boys by simply stretching the prepuce daily for 3 months. Topical steroids have also been used effectively, resolving phimosis 68.2% to 95%. Circumcision is a surgical procedure removing foreskin to allow a non-covered glans. Jewish and Muslim boys undergo this procedure routinely, and >50% of US boys get circumcised at birth. Medical indications are penile malignancy, traumatic foreskin injury, recurrent attacks of severe balanoposthitis (inflammation of the glans and foreskin), and recurrent urinary tract infections.

Pedersini et al., (2017) evaluated the functional and cosmetic outcomes of “trident” preputial plasty using a modified-triple incision for surgically managing phimosis in children ages 3-15. All patients seen in a 1 year period who were unable to retract the foreskin and had posthitis or balanoposthitis or ballooning of the foreskin during urination were included and treated initially with a two-month trial of topic corticosteroids. Only the patients unresponsive to corticosteroids were treated with the "trident" preputial plasty. At 12 months post-surgery, 97.6% (all but one of the 41 subjects) of patients were able to retract the prepuce, and cosmetics and function were satisfactorily restored.

Phimosis is apparently not a highlight in medical school curriculum, and parents often seek attention for other issues that lead to the diagnosis of phimosis. Like the tight material lining the neck of a shirt, the prepuce can be given a prolonged static stretch, and, over time, may retract appropriately. Or, cutting the shirt material may be necessary for long term success. Similarly, surgical intervention such as circumcision or the newer “trident” preputial plasty may be required.

Chan, Ivy HY and Wong, Kenneth KY. (2016). Common urological problems in children: prepuce, phimosis, and buried penis. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 22(3):263–9. DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154645

Pedersini, P, Parolini, F, Bulotta, AL, Alberti, D. (2017). "Trident" preputial plasty for phimosis in childhood. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 13(3):278.e1-278.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.01.024

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./