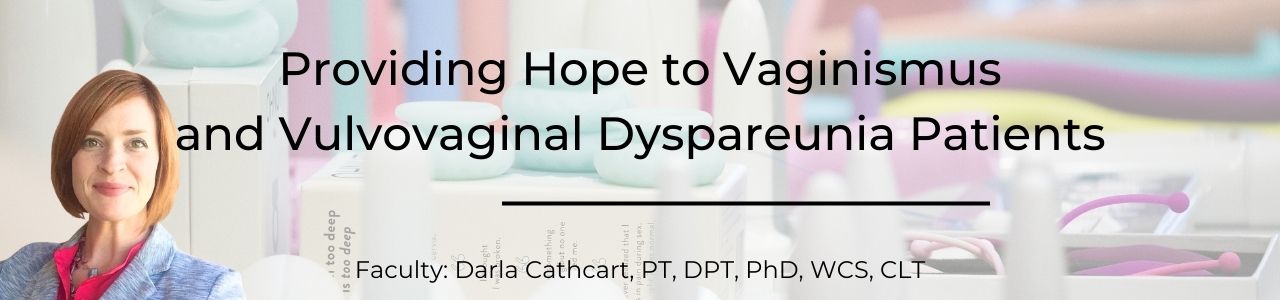

Darla Cathcart, PT, DPT, Ph.D., WCS, CLT graduated from Louisiana State University (Shreveport, LA) with her physical therapy degree, performed residency training in Women’s Health PT at Duke University, and received her Ph.D. from the University of Arkansas Medical Sciences. Her dissertation research focus was on using non-invasive brain stimulation to augment behavioral interventions for women with lifelong vaginismus, and her ongoing line of research will continue to center around pain with intercourse. Darla is part of Herman & Wallace's core faculty and recently launched her own course Vaginismus and Vulvovaginal Dyspareunia. She sat down with the Pelvic Rehab Report to discuss working with vaginismus and vulvovaginal dyspareunia patients.

I believe one of the most important things that we as pelvic therapists can do for patients experiencing vaginismus and vulvovaginal dyspareunia is to offer HOPE!

These patients often arrive at therapy with a belief that something is uniquely wrong with them. Often, they have been to more than a handful of other doctors and care providers who are unfamiliar with pelvic floor problems causing pain with sex (which is substantiated by the research) who have maybe given them messages of "I can't find anything wrong with you" and "You just need to relax."

If I had a dollar for every time a patient told me that another care provider told them to "Just drink a glass of wine before sex to help you relax" (palm to forehead!)...These messages often cause these patients to feel as if their pain with sex is made up in their heads, or that a scary diagnosis is being overlooked.

Unfortunately, unless they have found a provider who can quickly identify that the patient has a musculoskeletal problem with the pelvic floor that needs a pelvic therapy referral, then the patient has often gone for many months, years, or even a decade or more without being properly heard or getting the right help.

When I sit down with a patient, after hearing a bit of that person's story, I typically start the conversation with "Thank you for sharing your story. I want you to know that you are not alone - a big percentage of my patients have pain with sex. I also want you to know that based on what you are telling me, you will likely get better as most of them have done."

Patients often express relief, sometimes disbelief, or both, mixed with some hope - a bit of "Ah, this person hears me and knows what I'm talking about, and says I can get better!" The belief of being able to get better, even if mixed with some doubt, is an extremely valuable start on their healing journeys.

There are many factors that the pelvic therapist could consider to facilitate conversations around pain with sex.

As with all of our patients seeking pelvic rehab, communication requires non-judgment and respecting a patient's boundaries. Asking a patient "Have you been sexually abused or had sexual trauma in the past?" can feel unnerving and alarming for a patient who is not ready to have that conversation with their pelvic therapist. However, asking a patient "Have you had any negative sexual experiences that you would like to share, that you feel may be impacting your symptoms?" allows the patient to decline until they feel ready to engage in such a conversation.

This softer approach lets the patient know that the therapist is open to a conversation about impactful events and respects that patient's autonomy in sharing that history. Putting the patient in the driver's seat is also critical. For instance, consider a patient who, theoretically, would benefit greatly from using vaginal trainers (dilators) but declines to use them. An approach of "but using trainers will be the only way to get better" may result in the patient quitting therapy, or worse, feeling traumatized from the therapy experience. Alternatively, affirming to patients that the treatments chosen are their prerogative keeps the path for ongoing healing and provider trust.

A statement of "Not using vaginal trainers is your choice, but we can always consider them again in the future if you change your mind. Let me talk you through the alternative treatments, and how their effects will differ from that of the vaginal trainer use" leaves the door open to return to that treatment down the road if the patient chooses, and also respects the choice of the patient in the moment. The key is to not be pushy about pursuing the undesired treatment down the road! It could be mentioned again, but use judgment and caution in the approach.

A final highlight is being sure to give patients space to share their story, as often they have not been heard by previous providers or their symptoms have been discounted.

My course Vaginismus and Vulvovaginal Dyspareunia, is scheduled for March 3rd and September 14th this year and takes a deep dive into the detail of how to make the rubber meet the road to not only get treatment started but to really help progress a patient into a satisfying sex life. This course was developed so that the participant could leave this course and understand how to really approach the examination, history taking, and step-by-step procedures in instructing and using vaginal trainers and other tools for patients having painful intercourse. Additionally, this course should increase the practitioner's confidence in incorporating instructions and education related to a patient's concerns about the female sexual cycle and response (arousal, desire, orgasm), sexual positioning, lubrication, and partner integration.

I recently assisted at a Pelvic Floor Level 2B course which has been updated with recent research, new sections, and less repetition from Pelvic Floor Level 1. In the course they mentioned this article which sparked a lively discussion and I had to learn more. It is rare to see a study with a large number of participants in pelvic health and especially with a vaginismus diagnosis.

Vaginismus is defined as a genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder along with dyspareunia under the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; Fifth Edition) in which penetration is often impossible due to pain and fear. Vaginismus is both a physical and psychological disorder as it exhibits both muscle spasms and fear/anxiety of penetration. Symptoms vary by severity. Common presentation is an inability or discomfort to insert/remove a tampon, pain with penetration, and complaints of “hitting a wall” in attempted penetration; and inability to participate in gynecological exams.

The authors of this study evaluated the severity of vaginismus. The penetrative history was used in addition to presentation at pelvic exam, and then given a level. There are 2 grading systems, Lamont and Pacik, that indicate the level of fear and anxiety about being touched. They found that those with severe vaginismus were Lamont levels 3 and 4, and Pacik level 5. For example, a Pacik Level 5 includes Lamont grade 4 “generalized retreat: buttocks lift up; thighs close, patient retreats” plus a visceral reaction such as “palpitations, hyperventilation, sweating, severe trembling, uncontrollable shaking, screaming, hysteria, wanting to jump off the table, a feeling of going unconscious, nausea, vomiting and even a desire to attack the doctor”.

The authors of this study evaluated the severity of vaginismus. The penetrative history was used in addition to presentation at pelvic exam, and then given a level. There are 2 grading systems, Lamont and Pacik, that indicate the level of fear and anxiety about being touched. They found that those with severe vaginismus were Lamont levels 3 and 4, and Pacik level 5. For example, a Pacik Level 5 includes Lamont grade 4 “generalized retreat: buttocks lift up; thighs close, patient retreats” plus a visceral reaction such as “palpitations, hyperventilation, sweating, severe trembling, uncontrollable shaking, screaming, hysteria, wanting to jump off the table, a feeling of going unconscious, nausea, vomiting and even a desire to attack the doctor”.

241 patients participated in this study, with a mean duration of 7.8 years. 70% of participants were a Lamont level 4 or Pacik level 5 at baseline. The authors looked at previous treatments tried and coping strategies; 74% had tried lube, 73% had tried dilators, 50% had tried Kegels, 28% had tried physical therapy, 3% had tried a surgical vestibulectomy. The full table 2 is in the article. Most participants had a mean of at least 4 failed treatments.

The aim was to help these women to achieve pain free intercourse after treatment. In order to tolerate the treatment, many were sedated with midazolam before the Q-tip test, and more sedation given as needed. The treatment lasted for about 30 minutes and consisted of:

- Q-tip test with as minimal sedation as possible to rule out vulvodynia and provoked vestibulodynia

- Digital exam of tolerance in order to assess the level of spasm in introitus. Graded 0 (no spasm) to 4 (severe spasm where digital insertion was difficult)

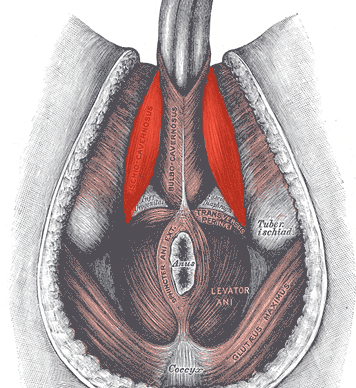

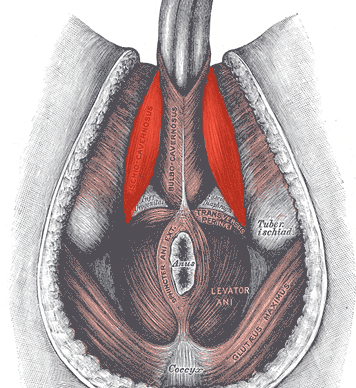

- Botox 50 U injections to right and left submucosal space near the bulbospongiosus muscle administered with a pediatric speculum placed. Additional Botox was injected submucosally into levator ani muscles if also in spasm/tight

- Injections 0.25% bupivacaine (a numbing agent) 1 mL increments along right and left lateral vaginal walls (9 mL per side) from cervix to introitus

- Progressive dilation; circumference 3 inches (#4), 4 inches (#5), 5 inches (#6)

- Reassessed with digital examination

- Re-insert #5 or #6 dilator and patient was awakened and taken to recovery

If the patient consented, her partner could be present during the procedure and was allowed to palpate the level of spasm with gloved digit and was educated on dilator insertion. The authors noted that many partners had a ‘profound’ experience.

A nurse worked with the couple for about two hours in the recovery room to help them be more comfortable moving the dilator in and out with minimal-to-no pain as the numbing agent lasts 6-8 hours. Three participants were treated each time and consented to meet each other. Patients were discharged with #4 dilator in place and asked to keep in until the next day. They were given Ibuprofen and sleeping aids as needed.

Day 1

Participants return with partners and progress up to larger sizes (#5 and #6). They participate in group counseling with the primary researcher Dr. Pacik. This lasted about 5 hours; and consisted of education of dilator progression, returning to intercourse and lubricants. If participants wished to have private counseling instead that was granted. Many exchanged contact information. They were encouraged to continue seeing their healthcare clinicians as indicated; sex therapists, physical therapists, psychologists.

Dilator Progression

Month 1

- 2 hours of dilator per day. Either in 1 sitting or 1 hour of dilator work x2 per day

- Progress to bigger sizes until #5 or #6 is comfortable

Month 2

- 1 hour of dilator use per day and continue toward larger sizes

Month 3

- 15-30 minutes of dilator use per day

Months 4-12

- 10-15 minutes of dilator use per day or every other day

During the counseling session post-procedure, the recommendations for returning to intercourse included:

- Delaying intercourse until #5 dilator was able to be easily inserted

- It is helpful to do 1 hour of dilator work before attempting intercourse for the first time

- If partner’s penis is larger progress to larger dilators (#7 - 6 inch circumference or #8 7 inch circumference)

- Goal of the first few attempts is to insert tip of dilator only

- Once tip can be inserted easily then progress to full penetration; restrain from thrusting

- Try “spooning position” if ‘leg lock’ occurs

- Try different positions with dilator work and intercourse to see what works best

71% of participants achieved pain-free coitus 5 weeks after the procedure. 2.5% could not achieve coitus within one-year period although they could use #5 or #6 dilators. The participants were given a validated outcome tool, the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), before and after the procedure and at 1-month, 3-months, 6-months, and 1-year; with significant improvement at each interval. The patients were followed for one year, and often remained in contact with the authors for much longer ranging from 16-months to 9-years.

The authors propose that use of dilators at the time of botox and post procedure counseling and support help participants ‘break through’, whereas previous treatment may not be as multidimensional and limit efficacy. Botox lasts 2-4 months and allowed for dilation progression.

Initially after reading this article the treatment seemed a little drastic to me, but then I considered the women with this level of vaginismus are often not coming into my clinic. They may need this level of structure, consistently, and multidimensional treatment as half measures have failed them. I am so glad they were persistent and found the help they needed.

Pacik, P., Geletta, S. Vaginismus Treatment: Clinical Trials Follow Up 241 Patients. Sex Med 2017;5:e114-e123

The female sexual response cycle is more than physical stimulation. As pelvic therapists, we frequently find ourselves treating pelvic pain that has interrupted a woman’s ability to enjoy her sexuality and sensuality. As physical therapists, we focus on the physical limitations and pain generators as a way of helping patients overcome their functional limitations. However, many of us find that once many of the physical symptoms have cleared with pelvic floor and fascial stretching, our patients are still apprehensive to engage physically, or they are not able to derive pleasure. There is clearly a gap that needs to be bridged that goes beyond pain.

Last year I taught my class, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment. I was honored and astounded to have Dee Hartmann, PT in my class. For those of you who do not know Dee, she has been a champion of our field for a long time, and she has been instrumental in elevating physical therapy as a first line of treatment in pelvic pain through her work, international leadership, and representation in multiple organizations, including APTA SOWH, ISSVD, IPPS, NVA, ISSWSH, and as an editor for the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Last year I taught my class, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment. I was honored and astounded to have Dee Hartmann, PT in my class. For those of you who do not know Dee, she has been a champion of our field for a long time, and she has been instrumental in elevating physical therapy as a first line of treatment in pelvic pain through her work, international leadership, and representation in multiple organizations, including APTA SOWH, ISSVD, IPPS, NVA, ISSWSH, and as an editor for the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

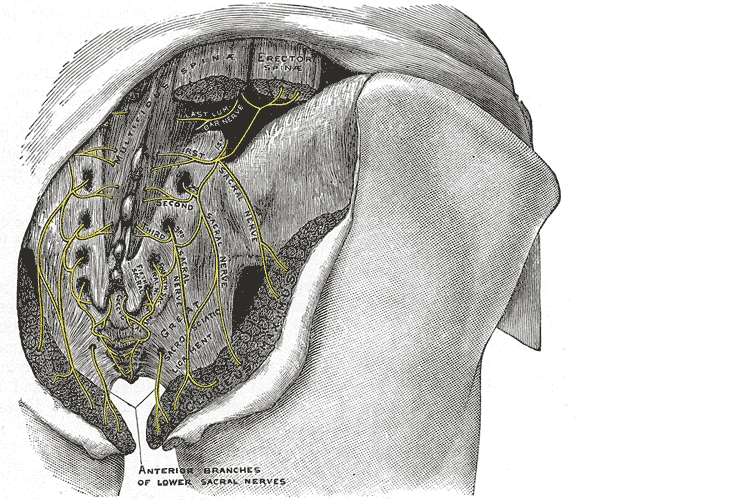

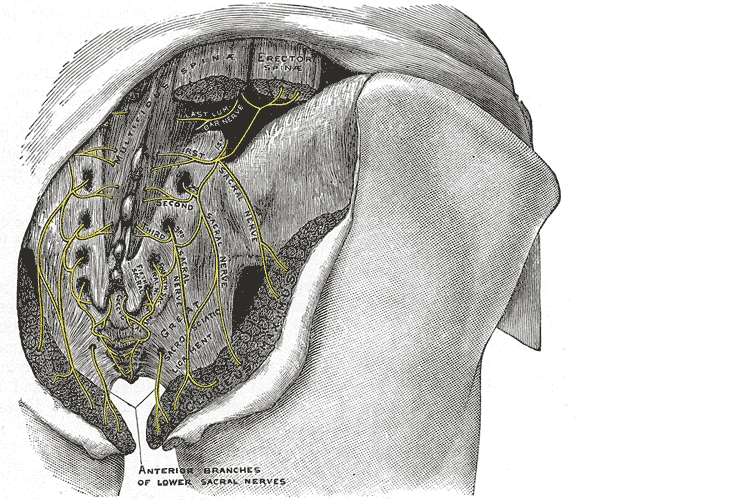

In this manual nerve class, I was teaching how to treat the path of the genitofemoral nerve, which affects the peri-clitoral tissues and sensation. We also covered manual therapy approaches to decrease restriction in the clitoral complex and improve the blood flow response in this region. Dee was fascinated and looped me into what she had been working on for the past several years. She has been working as part of a company called Vulvalove with her partner, sex therapist, Elizabeth Wood on studying and teaching women how to recapture their sensuality. Immediately, we wanted to combine forces in some way to present a way to approach these issues. So, when Dee invited me to present with Elizabeth and her at the Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association (CSM) this year, I was humbled and excited to jump on board.

With improved tissue mobility in the clitoral and vaginal area, blood flow is able to improve through any previously restricted tissues. With any manual therapy or soft tissue work, it is expected that cutaneous circulation of blood and lymph will alter. In studies, a measure of this blood flow, VPA (Vaginal Pulse Amplitude) is higher in the arousal than the non-arousal state in women.4 “The first measurable sign of sexual arousal is an increase in the blood flow. This creates the engorged condition, elevates the luminal oxygen tension and stimulates the production of surface vaginal fluid by increased plasma”.5 Manual therapy can likely affect this.1,2. During our CSM talk, I will discuss the neurovascular anatomy and will have a brief video of manual techniques to enhance these pathways in my portion of the presentation.

In the 19th century, female orgasm and sensuality was believed to be more vaginal, but as the 20th century unfolded, understanding of the clitoral tissues improved. More recent research reveals the origin of female pleasure is more complex, involving the clitoris, vulva, vagina, and uterus.3 However, female response is more complicated than just anatomy below the waist.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is a measure of autonomic nervous system health and the ability to flux between sympathetic and parasympathetic states. Autogenic training and meditation or mindfulness have been shown in multiple studies to improve HRV. A study by Stanton in 2017 demonstrated that even one session of autogenic training can increase HRV and VPA (Vaginal Pulse Amplitude, a measure of arousal). In our talk at CSM, Dee will cover the role of autogenics and how to specifically and practically use our autonomic state to influence our perception and feeling of pleasure. Dee will also cover extensive clitoral anatomy to have a better understanding of how this intricate complex functions and is structured in women.

Elizabeth Wood, a former sex therapist who is now a sex educator, will then present on the arousal cycle and what can be done physiologically to prepare the arousal network for climax. Elizabeth will help us to better define and understand the roles of arousal, calibration, and exploring sensuality, including exercises to help a patient have a more fulfilling experience once the physical pain is resolved. As Elizabeth says, “Knowledge is an antidote to shame and an invitation to pleasure”.

If you will be at CSM, please come join us at the opening session, Thursday February 13 from 8am-10am (PH2540), “Now That The Pain Is Gone, Where’s the Pleasure”.

If you can’t make it to CSM, I hope to see you at one of my nerve classes, “Lumbar Nerve Manual Therapy and Assessment” this year in Madison, WI April 24-26 or Seattle, WA October 16-18 to further explore manual therapies to improve sensation and neural feedback loops and to continue this conversation!

1. Portillo-Soto, A., Eberman, L. E., Demchak, T. J., & Peebles, C. (2014). Comparison of blood flow changes with soft tissue mobilization and massage therapy. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20(12), 932-936.

2. Ramos-González, E., Moreno-Lorenzo, C., Matarán-Peñarrocha, G. A., Guisado-Barrilao, R., Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M. E., & Castro-Sánchez, A. M. (2012). Comparative study on the effectiveness of myofascial release manual therapy and physical therapy for venous insufficiency in postmenopausal women. Complementary therapies in medicine, 20(5), 291-298.

3. Colson, M. H. (2010). Female orgasm: Myths, facts and controversies. Sexologies, 19(1), 8-14.

4. Rogers, G. S., Van de Castle, R. L., Evans, W. S., & Critelli, J. W. (1985). Vaginal pulse amplitude response patterns during erotic conditions and sleep. Archives of sexual behavior, 14(4), 327-342.

5. Stanton, A., & Meston, C. (2017). A single session of autogenic training increases acute subjective and physiological sexual arousal in sexually functional women. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 43(7), 601-617.

Mia Fine, MS, LMFT, CST joins the Herman & Wallace faculty in 2020 with her new course on Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists! The new course is launching this April 4-5, 2020 in Seattle, WA; Lecture topics include bio-psycho-social-spiritual interviewing skills, maintaining a patient-centered approach to taking a sexual history, and awareness of potential provider biases that could compromise treatment. Labs will take the form of experiential practice with Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual-Sexual Interviewing Skills, case studies and role playing. Check out Mia's interview with The Pelvic Rehab Report, then join her for Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists!

Tell us about yourself, Mia!

Tell us about yourself, Mia!

My name is Mia Fine, MS, LMFT, CST and I’ve been a Licensed Marriage and Family therapist for four years. I am an AASECT Certified Sex Therapist and my private practice is Mia Fine Therapy, PLLC. I see these kinds of patients: folks with Erectile Dysfunction, Pre-mature Ejaculation, Vaginismus, Dyspareunia, Desire Discrepancy, LGBTQ+, Ethical Non-monogamy, Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, Relational Concerns, Improving Communication.

What can you tell us about the new course?

This course will offer a great deal of current and empirically-founded sex therapy and sex education resources for both the provider as well as the patient. This course will add the extensive skills of interviewing for sexual health. It also offers the provider a new awareness and self-knowledge on his/her/their own blind spots and biases.

How will skills learned at this course allow practitioners to see patients differently?

Human beings are hardwired for connection, intimacy, and pleasure. Our society often tells us that there is something wrong with us, or that we are defective, for wanting a healthy sex life and for addressing our human needs/sexual desires. This course will broaden the provider’s scope of competence in working with patients who experience forms of sexual dysfunction and who hope to live their full sexual lives.

What inspired you to create this course?

This course was inspired by the need for providers who work with pelvic floor concerns to be trained in addressing and discussing sexual health with their patients.

What resources were essential in creating your course?

Becoming a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and a Certified Medical Family Therapist requires three years of intensive graduate school. Additionally, a minimum of two years of training to become an AASECT Certified Sex Therapist and hundreds of hours of direct client contact hours, supervision, and consultation. I attend numerous sex therapy trainings and continuing education opportunities on a regular and ongoing basis. I also train incoming sex therapists on current modalities and working with vulnerable client populations.

How do you think these skills will benefit a clinician in their practice?

It is vital that providers working with pelvic floor concerns have the necessary education and training to work with patients on issues of sexual dysfunction. It is also important that providers be aware of their own biases and be introduced to the various sexual health resources available to providers and patients.

What is one important technique taught in your course that everybody should learn?

Role playing sexual health interview questions is an important experience in feeling the discomfort that many providers feel when asking sexual health questions. This offers insight not only into the provider experience but also the patient’s experience of uncomfortability. Role playing this dynamic illustrates the very real experiences that show up in the therapeutic context.

Sexuality is core to most human beings’ identity and daily experiences. When there are concerns relating to our sexual identity, sexual health, and capacity to access our full potential, it affects our quality of life as well as our holistic well-being. Working with folks on issues of sexual health and decreasing sexual dysfunction encourages awareness and encourages healing. Imagining a world where human beings don’t walk around holding shame or traumatic pain is imaging a world of health and happiness.

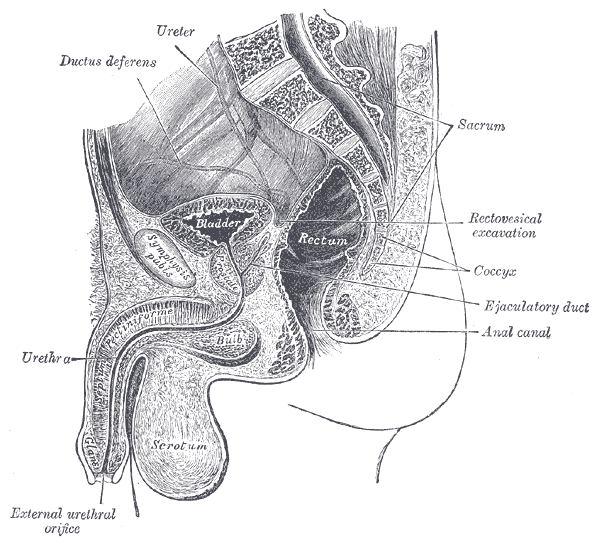

Often pelvic floor therapists see men for post-prostatectomy urinary leakage. However, at least for me, that quickly led to seeing male patients for pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction. Male sexual dysfunction is a broad category and can consist of erectile dysfunction (ED), ejaculation disorders including premature ejaculation (PE), and low libido -- often there is a pelvic floor muscle (PFM) dysfunction component. Conservative treatment frequently consists of pharmacological and lifestyle changes for this population.

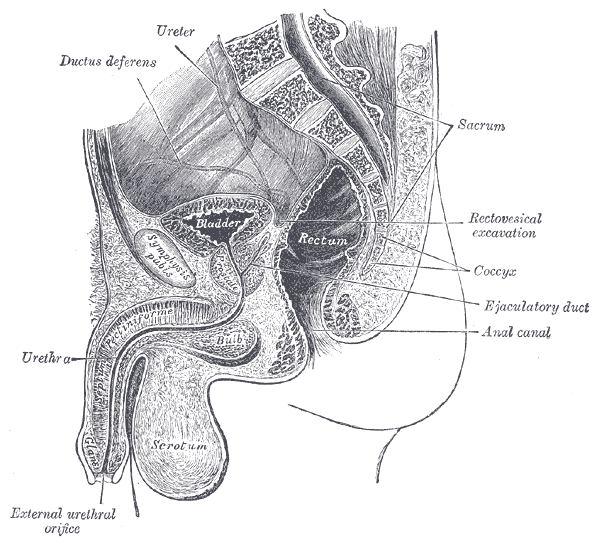

In normal sexual function, the male superficial pelvic floor musculature (bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernosus) work together to create increased intracavernosus pressure by limiting venous return, resulting in an erection. Ejaculation is created by rhythmic contractions of the bulbocavernosus muscle.

The authors of this systematic review were curious if pelvic floor muscle training was effective for treating erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation diagnoses, and if so to determine whether there is a treatment protocol. Ten studies were found that met the inclusion criteria, five that focused on ED and five that focused on PE. In total, there were 668 participants ranging in age from 30-59 years old. Studies were excluded if participants were post-prostatectomy and/or had a neurological diagnosis. The intervention was a pelvic floor program, and pelvic floor muscle contractions were either taught or supervised. Studies also included supportive treatment including biofeedback, lifestyle changes, and electrical stimulation.

The authors of this systematic review were curious if pelvic floor muscle training was effective for treating erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation diagnoses, and if so to determine whether there is a treatment protocol. Ten studies were found that met the inclusion criteria, five that focused on ED and five that focused on PE. In total, there were 668 participants ranging in age from 30-59 years old. Studies were excluded if participants were post-prostatectomy and/or had a neurological diagnosis. The intervention was a pelvic floor program, and pelvic floor muscle contractions were either taught or supervised. Studies also included supportive treatment including biofeedback, lifestyle changes, and electrical stimulation.

The studies focused on erectile dysfunction listed a combination of hormonal, psychogenic, arteriogenic, and venogenic causes. The pelvic floor training ranged from 5-20 visits over 3-4 months and included a home exercise program. Pelvic floor training was similar in all studies and consisted of maximal quick contractions over one second and submaximal endurance holds over 6-10 seconds. Compliance to home exercise program was not assessed. Between 35% and 47% of participants reported a full resolution of symptoms. Subjective improvements were supported by improved maximal anal pressure and intracavernosus pressure. One study used the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and showed significant improvement (p<0.05).

The studies focused on premature ejaculation noted participants had either lifelong or secondary PE. The pelvic floor training in these studies ranged from 12-20 sessions over 1-3 months. All studies used electrical stimulation as part of the pelvic floor muscle training. Four studies also used biofeedback. Only one study listed a home exercise program but did not report on compliance. The pelvic floor muscle training was compared to nothing in three studies, and to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) in the other two studies. Patient reported full resolution of symptoms was 55-83% in two studies, and there was a significant improvement in delay in heterosexual penetrative ejaculation (p<0.05) in three studies.

For both erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation, pelvic floor muscle exercise prescription was 2-3 times per week with pelvic floor muscle contractions both maximal quick contractions and submaximal endurance holds. Significant results were shown with participants who were taught pelvic floor muscle contractions through a combination of verbal and physical means (typically biofeedback). Specific verbal cues were not reported. The authors suggest that electrical stimulation was helpful for training recruitment patterns; however, there was not a significant difference in outcomes for those with ED when using electrical stimulation. The authors suggest that pelvic floor muscle training can be part of a conservative treatment. It may be used with oral pharmacology for quick results, and may be beneficial with electrical stimulation and biofeedback, though more research is indicated.

If you are interested in learning more about treating male patients, consider attending Male Pelvic Floor: Function, Dysfunction, and Treatment!

Myers, C., Smith, M. “Pelvic floor muscle training improves erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation: a systematic review” Physiotherapy 105 (2019) 235–243

Most people are told that inguinal hernia repair is a low risk surgery. While death or severe injury is rare, penile or testes pain after hernia repair is not a novel or recent finding. In 1943, Magee first discussed patients having genitofemoral neuralgia after appendix surgery. By 1945, both Magee and Lyons stated that surgical neurolysis gave relief of genital pain following surgical injury (neurolysis is a surgical cutting of the nerve to stop all function). However, it should be noted that with neurolysis, sensory loss will also occur, which is an undesired symptom for sexual function and pleasure. In 1978 Sunderland stated genitofemoral neuralgia was a well-documented chronic condition after inguinal hernia repair.

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

In 1999 Stark et al noted pain reports as high as 63% post hernia repair. The highest rates of genitofemoral neuralgia are reported with laparoscopic or open hernia repair (Pencina, 2001). The mechanism for GF neural entrapment is entrapment within scar or fibrous adhesions and parasthesia along the genitofemoral nerve (Harms 1984, Starling and Harms 1989, Murovic 2005, and Ducic 2008). It is well known that scar and adhesion densify and visceral adhesions increase for years after surgery. Thus, symptoms can increase long after the surgery or may take years to develop. In 2006, Brara postulated that mesh in the region can contribute to subsequent genitofemoral nerve tethering which can be exacerbated by mesh in the inguinal or the retroperitoneal space. With an anterior mesh placement, there is no fascial protection left for the genitofemoral nerve.

Genitofemoral neuralgia is predominately reported as a result of iatrogenic nerve damage during surgery or trauma to the inguinal and femoral regions (Murovic et al, 2005). However, genitofemoral neuropathy can be difficulty and elusive to diagnose due to overlap with other inguinal nerves (Harms, 1984 and Chen 2011).

In my clinical experience, I have seen such symptoms after hernia repair, but also after procedures near the inguinal region such as femoral catheters for heart procedures, appendectomies, and occasionally after vasectomy.

As a pelvic PT, what are we to do with this information? First off, we can realize that all pelvic neuropathy is not necessarily due to the pudendal nerve. In the anterior pelvis, there is dual innervation from the inguinal nerves off the lumbar plexus as well as the dorsal branch of the pudendal nerve. When patients have a history of inguinal hernia repair, we can consider the genitofemoral nerve as a source of pain. Medicinally, the only research validated options for treatment are meds such as Lyrica or Gabapentin that come with drowsiness, dizziness and a score of side effects. Surgically neurectomy or neural ablation are options with numbness resulting, however, many patients do not want repeated surgery or numbness of the genitals. As pelvic therapists, we can manually fascially clear the path of the nerve from L1/L2, through the psoas, into and out of the canal and into the genitals. We can also manually directly mobilize the nerve at key points of contact as well as doing pain free sliders and gliders and then give the patient a home program to maintain mobility. Pelvic manual therapy can offer a low risk, side-effect free option to ameliorate the sequella of inguinal hernia repair. Come join us at Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment in Chicago this Spring to learn how to effectively treat all the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Cesmebasi, A., Yadav, A., Gielecki, J., Tubbs, R. S., & Loukas, M. (2015). Genitofemoral neuralgia: a review. Clinical Anatomy, 28(1), 128-135.

Lyon, E. K. (1945). Genitofemoral causalgia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 53(3), 213.

Magee, R. K. (1943). Genitofemoral Causalgia: New Syndrome. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 98(3), 311.

Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1978

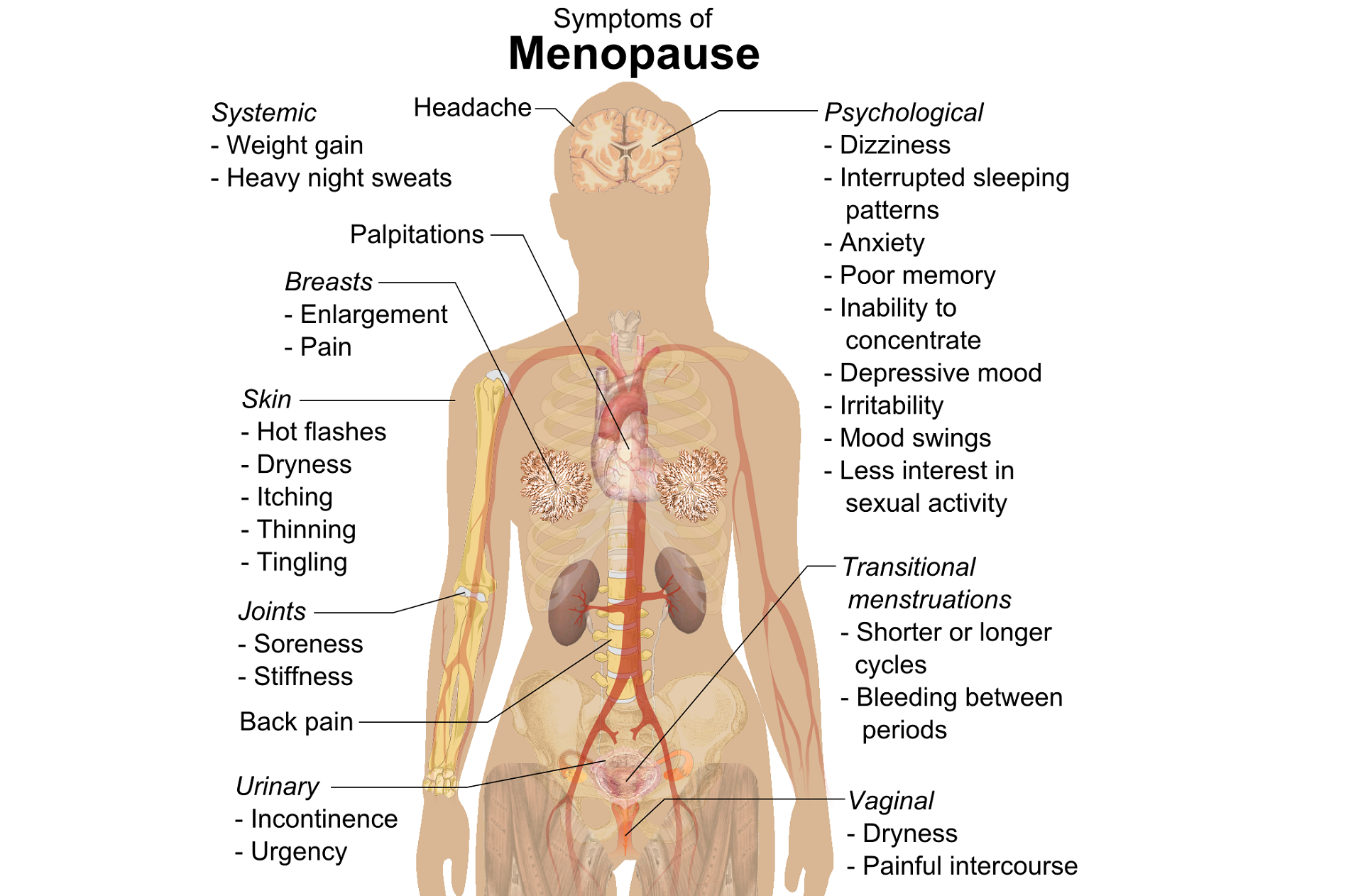

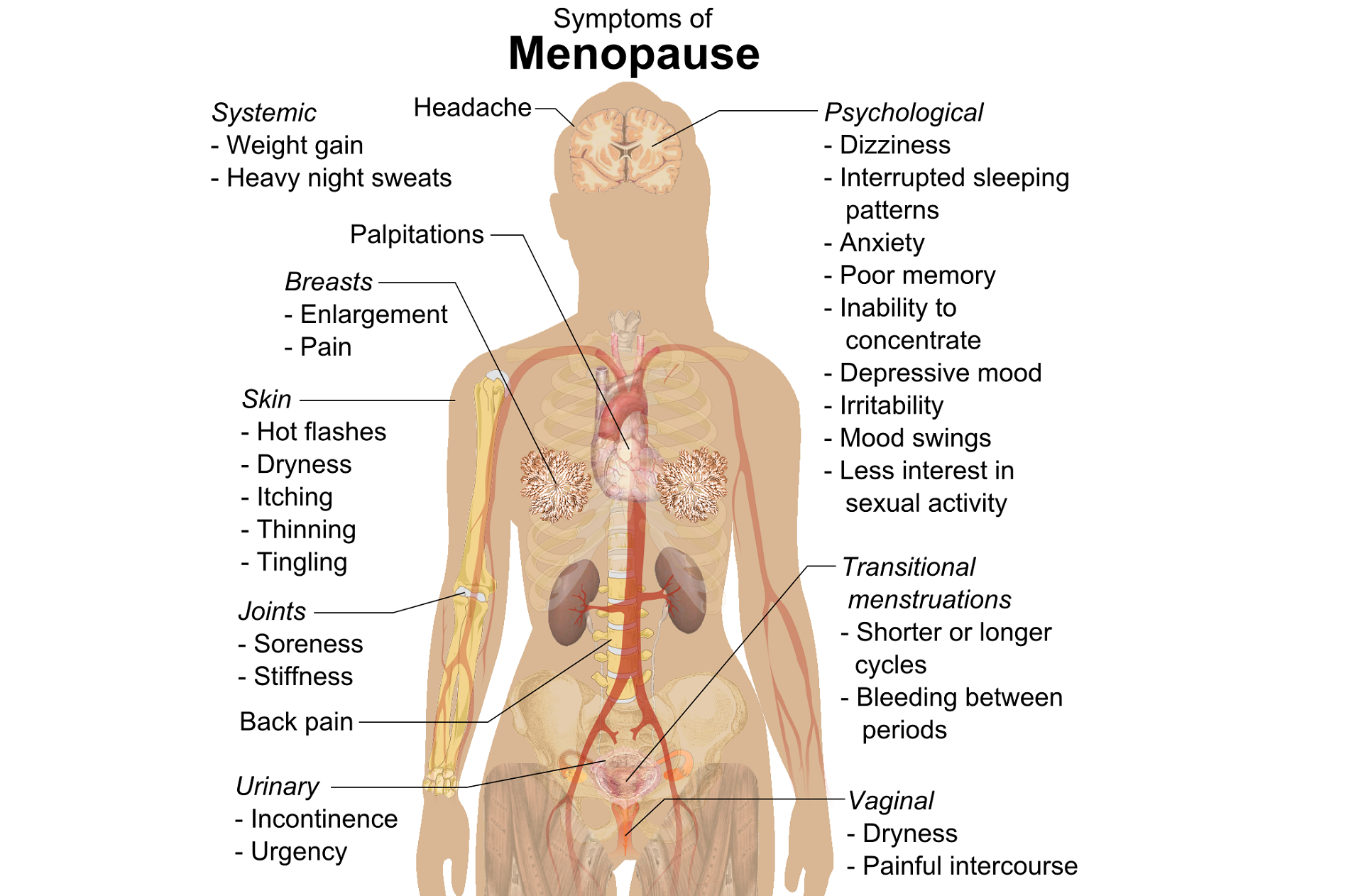

A question that often comes up in conversation around menopause is that of pelvic health – the effects on bladder, bowel or sexual health…what works, what’s safe, what’s not? Is hormone therapy better, worse or the same in terms of efficacy when compared to pelvic rehab? Do we have a role here?

An awareness of pelvic health issues that arise at menopause was explored in Oskay’s 2005 paper ‘A study on urogenital complaints of postmenopausal women aged 50 and over’ stating ‘…Urinary incontinence and sexual problems, particularly decline in sexual desire, are widespread among postmenopausal women. Frequent urinary tract infections, obesity, chronic constipation and other chronic illnesses seem to be the predictors of UI.’

Moller’s 2006 paper explored the link between LUTS (Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms) and sexual activity at midlife: the paper discussed how lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have a profound impact on women’s physical, social, and sexual well being, and confirmed that LUTS are likely to affect sexual activity. However, they also found that conversely, sexual activity may affect the occurrence of LUTS – in their study a questionnaire was sent to 4,000 unselected women aged 40–60 years, and they found that compared to women having sexual relationship, a statistically significant 3 to 6 fold higher prevalence of LUTS was observed in women with no sexual relationship. They also found that women who ceased sexual relationship an increase in the de novo occurrence of most LUTS was observed, concluding that ‘…sexual inactivity may lead to LUTS and vice versa’.

Moller’s 2006 paper explored the link between LUTS (Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms) and sexual activity at midlife: the paper discussed how lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have a profound impact on women’s physical, social, and sexual well being, and confirmed that LUTS are likely to affect sexual activity. However, they also found that conversely, sexual activity may affect the occurrence of LUTS – in their study a questionnaire was sent to 4,000 unselected women aged 40–60 years, and they found that compared to women having sexual relationship, a statistically significant 3 to 6 fold higher prevalence of LUTS was observed in women with no sexual relationship. They also found that women who ceased sexual relationship an increase in the de novo occurrence of most LUTS was observed, concluding that ‘…sexual inactivity may lead to LUTS and vice versa’.

So, who advises women going through menopause about issues such as sexual ergonomics, the use of lubricants or moisturisers, or provide a discussion about the benefits of local topical estrogen? As well as providing a skillset that includes orthopaedic assessment to rule out any musculo-skeletal influences that could be a driver for sexual dysfunction? That would be the pelvic rehab specialist clinician! Tosun et al asked the question ‘Do stages of menopause affect the outcomes of pelvic floor muscle training?’ and the answer in this and other papers was yes; with the research comparing pelvic rehab vs hormone therapy vs a combination approach of pelvic rehab and topical estrogen providing the best outcomes. Nygaard’s paper looked at the ‘Impact of menopausal status on the outcome of pelvic floor physiotherapy in women with urinary incontinence’ and concluded that : ‘…(both pre and postmenopausal women) benefit from motor learning strategies and adopt functional training to improve their urinary symptoms in similar ways, irrespective of hormonal status or HRT and BMI category’.

We must also factor in some of the other health concerns that pelvic health can impact at midlife for women – Brown et al asked the question ‘Urinary incontinence: does it increase risk for falls and fractures?’ They answered their question by concluding that ‘‘… urge incontinence was associated independently with an increased risk of falls and non-spine, nontraumatic fractures in older women. Urinary frequency, nocturia, and rushing to the bathroom to avoid urge incontinent episodes most likely increase the risk of falling, which then results in fractures. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of urge incontinence may decrease the risk of fracture.’

If you are interested in learning more about pelvic health, sexual function and bone health at Menopause, consider attending Menopause Rehabilitation and Symptom Management.

Sexual activity and lower urinary tract symptoms’ Møller LA1, Lose G. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 Jan;17(1):18-21. Epub 2005 Jul 29.

A study on urogenital complaints of postmenopausal women aged 50 and over. Oskay UY1, Beji NK, Yalcin O. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005 Jan;84(1):72-8.

Do stages of menopause affect the outcomes of pelvic floor muscle training? Tosun ÖÇ1, Mutlu EK, Tosun G, Ergenoğlu AM, Yeniel AÖ, Malkoç M, Aşkar N, İtil İM. Menopause. 2015 Feb;22(2):175-84. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000278.

‘Impact of menopausal status on the outcome of pelvic floor physiotherapy in women with urinary incontinence.’ Nygaard CC1, Betschart C, Hafez AA, Lewis E, Chasiotis I, Doumouchtsis SK. Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Dec;24(12):2071-6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2179-7. Epub 2013 Jul 17

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a debilitation complication of radical prostatectomy, which is a treatment for prostate cancer. ED is caused by a variety of causes, diabetic vasculopathy, smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, psychological issues, peripheral vascular disease and medication; we will focus on post-prostatectomy ED and the role of penile rehabilitation in its management.

Post-prostatectomy-related Erectile dysfunction

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Research on penile hemodynamics in these patients have shown that venous leakage is also implicated in its pathophysiology. An injury to the neurovascular bundles likely leads to smooth muscle cell death, which then leads to irreversible veno-occlusive disease.

There is a potential role of hypoxia in stimulating growth factors (TGF-beta) that stimulate collagen synthesis in cavernosal smooth muscle. Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) was found to suppress the effect of TGF-β1 on collagen synthesis.

Role of Penile Rehabilitation

The goal of Penile Rehabilitation is to limit and reverse ED in post-prostatectomy patients. The idea is to minimize fibrotic changes during the period of “penile quiescence” after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Several approaches have been tried, including PGE1 injection, vacuum devices, and phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors.

Mulhall and coworkers followed 132 patients through an 18-month period after they were placed in “rehabilitation” or “no rehabilitation” groups after radical prostatectomy, and 52% of those undergoing rehabilitation (sildenafil + alprostadil) reported spontaneous functional erections, compared with 19% of the men in the no-rehabilitation group 2.

Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1)

Alprostadil is a vasodilatory prostaglandin E1 that can be injected into the penis or placement in the urethra in order to treat ED. Montorsi, et al. studied the use of intracorporeal injections of alprostadil starting at 1 month after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and reported a higher rate of spontaneous erections after 6 months compared with no treatment 3. Gontero, et al. investigated alprostadil injections at various time points after non–nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and found that 70% of patients receiving injections within the first 3 months were able to achieve erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 40% of patients receiving injections after the first 3 months 4.

Vacuum constriction device (VCD)

VCD is an external pump that is used to get and maintain an erection. Raina, et al evaluated the daily use of a VCD beginning within two months after radical prostatectomy, and reported that after 9 months of treatment, 17% of patients using the device had return of natural erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 11% of patients in the nontreatment group 4.

PDE-5 Inhibitors

PDE-5 inhibitors (such as Sildenafil) are the first-line treatment for ED of many etiologies. Several studies have shown that the use of PDE-5 inhibitors might lead to an overall improvement in endothelial cell function in the corpus cavernosum. Chronic use of oral PDE-5 inhibitors suggest a beneficial effect on endothelial cell function. Desouza, et al. concluded that daily sildenafil improves overall vascular endothelial cell function. However, Zagaja, et al. found that men taking oral sildenafil within the first 9 months of a nerve-sparing procedure did not have any erectogenic response 4.

Overall, accumulating scientific literature is suggesting that penile rehabilitation therapies have a positive impact on the sexual function outcome in post-prostatectomy patients. It must be noted that these methods do not cure ED and should be used with caution.

1Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701-1705.

2Mulhall J, Land S, Parker M, et al. The use of an erectogenic pharmacotherapy regimen following radical prostatectomy improves recovery of spontaneous erectile function. J Sex Med. 2005; 2:532-540.

3Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Strambi LF, et al. Recovery of spontaneous erectile function after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy with and without early intracavernous injections of alprostadil: results of a prospective, randomised trial. J Urol. 1997;158:1408-1410.

4Gontero P, Fontana F, Bagnasacco A, et al. Is there an optimal time for intracavernous prostaglandin E1 rehabilitation following non- nerve sparing radical prostatectomy? Results from a hemodynamic prospective study. J Urol. 2003;169:2166-2169.

Managing a medical crisis such as a cancer diagnosis can be overwhelming for an individual. Faced with choices about medical options, dealing with disruptions in work, home and family life often leaves little energy left to consider sexual health and intimacy. Maintaining closeness, however, is often a goal within a partnership and can aid in sustaining a relationship through such a crisis. The research is clear about cancer treatment being disruptive to sexual health, yet intimacy is a larger concept that may be fostered even when sexual activity is impaired or interrupted. Last year, when I was asked to speak to the Pacific NW Prostate Cancer Conference about intimacy, I was pleasantly surprised to find a rich body of literature about maintaining intimacy despite a diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

If the patient brings up sexual health, or we encourage the conversation, there are many research-based suggestions we can provide to encourage recovery of intimacy, several are listed below.

- Manage general health, fitness, nutrition, sleep, anxiety and stress

- Redefine sex as being beyond penetration, consider other sexual practices such as massage/touch, cuddling, talking, use of vibrators, medication, aids such as pumps (Usher et al., 2013)

- Participate in couples therapy to understand partners’ needs, address loss, be educated about sexual function (Wittman et al., 2014; Wittman et al., 2015)

- Participate in “sensate focus” activities (developed by Masters & Johnson in 1970’s as “touch opportunities”) with appropriate guidance (Weiner & Avery-Clark 2017)

Within the context of this information, there is opportunity to refer the patient to a provider who specializes in sexual health and function. While some rehabilitation professionals are taking additional training to be able to provide a level of sexual health education and counseling, most pelvic health providers do not have the breadth and depth of training required to provide counseling techniques related to sexual health- we can, however, get the conversation started, which in the end may be most important.

In the men’s health course, we further discuss sexual anatomy and physiology, prostate issues, and look at the research describing models of intimacy and what worked for couples who did learn to renegotiate intimacy after prostate cancer.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2009, April). Sexual intimacy in heterosexual couples after prostate cancer treatment: What we know and what we still need to learn. In Urologic oncology: seminars and original investigations (Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 137-143). Elsevier.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2013). Sexual Values as the Key to Maintaining Satisfying Sex After Prostate Cancer Treatment : The Physical Pleasure–Relational Intimacy Model of Sexual Motivation. Archives of sexual behavior, 42(8), 1637-1647.

Gilbert, E., Ussher, J. M., & Perz, J. (2010). Renegotiating sexuality and intimacy in the context of cancer: the experiences of carers. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 998-1009.

Hawkins, Y., Ussher, J., Gilbert, E., Perz, J., Sandoval, M., & Sundquist, K. (2009). Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer nursing, 32(4), 271-280.

Higano, C. S. (2012). Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(30), 3720-3725.

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E., Wong, W. T., & Hobbs, K. (2013). Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nursing, 36(6), 454-462.

Weiner, L., Avery-Clark, C. (2017). Sensate Focus in Sex Therapy: The Illustrated Manual. Routledge, New York.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., An, L., Palapattu, G., & Montie, J. E. (2014). Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(9), 2509-2515.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., Crossley, H., An, L., ... & Montie, J. E. (2015). What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: toward the development of a conceptual model of couples' sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. The journal of sexual medicine, 12(2), 494-504.

In a previous post on The Pelvic Rehab Report Sagira Vora, PT, MPT, WCS, PRPC told us how "women with sexually adverse experiences tend to have impaired genital response when in consensual sexual situations, however, women who do not have sexual abuse histories and but have sexual pain tend to have appropriate genital response." Today Sagira helps us understand how the pelvic floor responds to consensual sexual activity in women with a history of sexual trauma.

Today we try to look for answers for questions that came up during the last blogs.

How does the cohort that has had adverse sexual experiences present? How do women with history of sexual trauma process sexual experiences? How does the pelvic floor present or respond to consensual sexual situations when a woman has been abused in the past?

How does the cohort that has had adverse sexual experiences present? How do women with history of sexual trauma process sexual experiences? How does the pelvic floor present or respond to consensual sexual situations when a woman has been abused in the past?

To answer these questions, it’s important to understand two facts about the pelvic floor. 1) the pelvic floor plays a role in emotional processing1, and 2) muscle activity in all muscles, including the pelvic floor, increases with exposure to stress and during anxiety evoking experiences2.

We explored in the last blog that women with sexual abuse histories responded with increased pelvic floor overactivity when watching movie clips with sexually threatening and consensual sexual content. Apparently, for women with sexual abuse history even consensual sexual situations can be experienced as threatening1.

Lehrer et. al. found overactivity in the neuronal and hormonal circuits that increase sexual arousal and activity. These circuits are already overactive in individuals who have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and increased activity can increase anxiety, fear and other symptoms of PTSD instead of normal sexual arousal and excitement during a sexual experience2. For the woman with PTSD this means that sexual arousal signals impending threat rather than pleasure1. And as we already learned in previous blogs and above that when humans feel threatened they respond by tightening muscles and most notably the pelvic floor muscle.

Significant co-relation is found between sexual abuse, subsequent PTSD and chronic pelvic pain3. Hooker et. al, found irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic pain, and physical and sexual abuse to be the most commonly diagnosed together4. More importantly, when patients were successfully treated for PTSD they continued to be 2.7 times more likely to have pelvic floor dysfunction and 2.4 times more likely to have sexual dysfunction. This builds the case for interventions that are multidisciplinary to help patients of abuse and sexual assault, with the pelvic floor therapist playing a significant role.

In the next blog, lets explore how the pelvic floor therapist can work with a counselor and a sex therapist to help the woman with sexual pain dysfunction.

Anna Padoa and Talli Rosenbaum. The overactive pelvic floor. Springer. 1st ed. 2016

Yehuda R, Lehrner A, Rosenbaum TY. PTSD and sexual dysfunction in men and women. J Sex Med. 2015:12(5):1107-19

Blok BF. Holstege G. The neuronal control of micturition and its relation to the emotional motor system. Prog Brain Res. 1996; 107:113-26

Para ML, Chen LP, Goranson EN, Sattler AL, Colbenson KM, Seime RJ, Et. al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnoses of somatic disorders. JAMA. 2013; 302:550-61

Hooker AB, van Moorst BR, van Haarst EP, Van Ootegehem NAM, van Dijken DKE, Heres MHB, Chronic pelvic pain: evaluation of the epidemiology, baseline characteristics, and clinical variables via a prospective and multidisciplinary approach. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 40:492-8