As I read about male phimosis, I thought about a shirt that just won’t go over my son’s big noggin. I tug and pull, and he screams as his blond locks stick up from static electricity. Ultimately, if I want this shirt to be worn, I either have to cut it or provide a prolonged stretch to the material, or my child will suffocate in a polyester sheath. This is remotely similar to the male with physiological phimosis.

In a review article, Chan and Wong (2016) described urological problems among children, including phimosis. They reported “physiological phimosis” is when the prepuce cannot be retracted because of a natural adhesion to the glans. Almost all normal male babies are born with a foreskin that does not retract, and it becomes retractable in 90% of boys once they are 3 years old. A biological process occurs, and the prepuce becomes retractable. In “pathological phimosis” or balanitis xerotica obliterans, the prepuce, glans, and sometimes even the urethra experience a progressive inflammatory condition involving inflammation of the glans penis, an unusually dry lesion, and occasional endarteritis. Etiology is unknown, but males by their 15th birthday report a 0.6% incidence, and the clinical characteristics include a white tip of the foreskin with a ring of hard tissue, white patches covering the glans, sclerotic changes around the meatus, meatal stenosis, and sometimes urethral narrowing and urine retention.

In a review article, Chan and Wong (2016) described urological problems among children, including phimosis. They reported “physiological phimosis” is when the prepuce cannot be retracted because of a natural adhesion to the glans. Almost all normal male babies are born with a foreskin that does not retract, and it becomes retractable in 90% of boys once they are 3 years old. A biological process occurs, and the prepuce becomes retractable. In “pathological phimosis” or balanitis xerotica obliterans, the prepuce, glans, and sometimes even the urethra experience a progressive inflammatory condition involving inflammation of the glans penis, an unusually dry lesion, and occasional endarteritis. Etiology is unknown, but males by their 15th birthday report a 0.6% incidence, and the clinical characteristics include a white tip of the foreskin with a ring of hard tissue, white patches covering the glans, sclerotic changes around the meatus, meatal stenosis, and sometimes urethral narrowing and urine retention.

This review article continues to discuss the appropriate treatment for phimosis (Chan & Wong 2016). Once phimosis is diagnosed, the parents of the young male need to be educated on keeping the prepuce clean. This involves retracting the prepuce gently and rinsing it with warm water daily to prevent infection. Parents are warned against forcibly retracting the prepuce. A study has shown complete resolution of the phimosis occurred in 76% of boys by simply stretching the prepuce daily for 3 months. Topical steroids have also been used effectively, resolving phimosis 68.2% to 95%. Circumcision is a surgical procedure removing foreskin to allow a non-covered glans. Jewish and Muslim boys undergo this procedure routinely, and >50% of US boys get circumcised at birth. Medical indications are penile malignancy, traumatic foreskin injury, recurrent attacks of severe balanoposthitis (inflammation of the glans and foreskin), and recurrent urinary tract infections.

Pedersini et al., (2017) evaluated the functional and cosmetic outcomes of “trident” preputial plasty using a modified-triple incision for surgically managing phimosis in children ages 3-15. All patients seen in a 1 year period who were unable to retract the foreskin and had posthitis or balanoposthitis or ballooning of the foreskin during urination were included and treated initially with a two-month trial of topic corticosteroids. Only the patients unresponsive to corticosteroids were treated with the "trident" preputial plasty. At 12 months post-surgery, 97.6% (all but one of the 41 subjects) of patients were able to retract the prepuce, and cosmetics and function were satisfactorily restored.

Phimosis is apparently not a highlight in medical school curriculum, and parents often seek attention for other issues that lead to the diagnosis of phimosis. Like the tight material lining the neck of a shirt, the prepuce can be given a prolonged static stretch, and, over time, may retract appropriately. Or, cutting the shirt material may be necessary for long term success. Similarly, surgical intervention such as circumcision or the newer “trident” preputial plasty may be required.

Chan, Ivy HY and Wong, Kenneth KY. (2016). Common urological problems in children: prepuce, phimosis, and buried penis. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 22(3):263–9. DOI: 10.12809/hkmj154645

Pedersini, P, Parolini, F, Bulotta, AL, Alberti, D. (2017). "Trident" preputial plasty for phimosis in childhood. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 13(3):278.e1-278.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.01.024

Myofascial release (MFR) can be one of your greatest treatment tools as a pelvic rehabilitation practitioner. Just in case you don’t think about fascia often here are a couple helpful things to remember. Fascia is the irregular connective tissue that covers the entire body, and it is the largest sensory system in the body, making it highly innervated. The mobilizing effect of MFR techniques occurs by stimulating various mechanoreceptors within the fascia (not by the actual force applied). MFR techniques can help to reduce tissue tension, relax hypertonic muscles, decrease pain, reduce localized edema, and improve circulation just to name a few physiological effects.

An interesting case report published in 2015 by the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1 offers a wonderful example of how a physical therapist used specific MFR techniques for a patient with clitoral phimosis and dyspareunia. The specific MFR techniques used helped to provide relief and restore mobility to the pelvic tissues for this patient.

An interesting case report published in 2015 by the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1 offers a wonderful example of how a physical therapist used specific MFR techniques for a patient with clitoral phimosis and dyspareunia. The specific MFR techniques used helped to provide relief and restore mobility to the pelvic tissues for this patient.

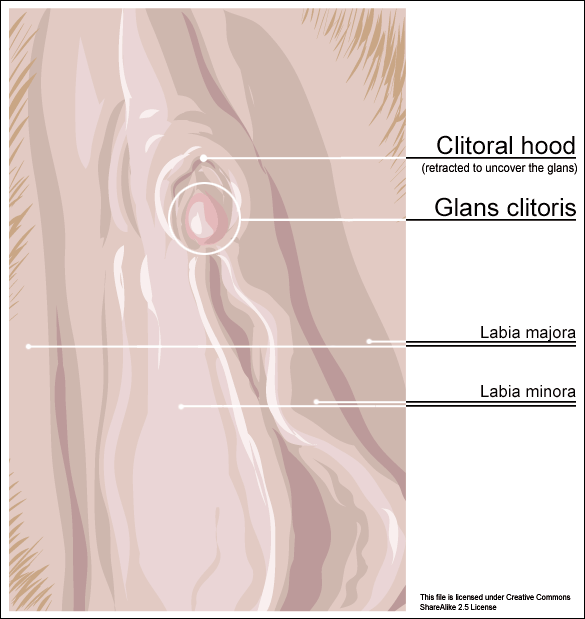

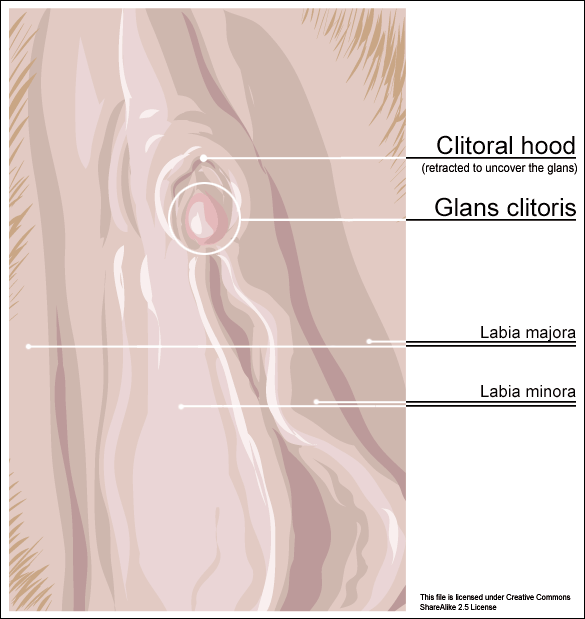

Clitoral phimosis is adherence between the clitoral prepuce (also known as the clitoral hood) and the glans. This condition can be the result of blunt trauma, chronic infection, inflammatory dermatoses, and poor hygiene. In this case report, the 41-year-old female patient had sustained a blunt trauma injury to the vulva (when her toddler son charged, contacting his head forcibly into her pubic region). She presented to physical therapy with complaints of dyspareunia, low back pain, a bruised sensation of her pubic region, vulvar pain provoked by sexual arousal, decreased clitoral sensitivity, and anorgasmia. The physical therapist completed an orthopedic assessment for the lower quarter (including spine and extremities), as well as a thorough pelvic floor muscle assessment.

Treatment for this patient addressed not only the pelvic complaints, but the lower quarter complaints as well. A detailed treatment summary for each visit is outlined in the case report. The clitoral MFR and stretching was performed by applying a small amount of topical lubricant to the clitoral prepuce. Then, a gloved finger or a cotton swab was used to stabilize the clitoris, a prolonged MFR or sustained stretch was applied in the direction away from the fixated clitoris by the therapist’s other finger. The therapist applied this technique along the entire length of the prepuce. The other physical therapy interventions this patient was treated with were stretching, joint mobilization, muscle energy techniques, transvaginal pelvic floor muscle massage, clitoral prepuce MFR techniques, biofeedback, Integrative Manual Therapy (IMT) techniques, nerve mobilization, and therapeutic and motor control exercises. Additionally, between the physical therapy evaluation and the second visit the patient did use topical Clobetasol 0.05% cream (commonly prescribed for vulvar dermatitis issues such as Lichen Sclerosis) for 30 days with no change to her clitoral phimosis.

After 11 sessions, the patient had resolution of dyspareunia, vulvar pain, pubic pain, and reduced low back pain. Also, the patient had 100% restored mobility of the clitoral prepuce, as well as normalized clitoral sensitivity and clitoral orgasm. The patient felt these improvements were still present at her 6-month follow-up interview over the phone. Current medical management for clitoral phimosis is surgical release or topical/injectable corticosteroids. Having a conservative treatment option, such as MFR, for this condition can be helpful for patients. As with most evolving treatment techniques, more research and studies are appropriate.

Not one health care professional had ever assessed the fascial mobility of the clitoris until this physical therapist did. This case report is an example of how MFR techniques can be effective treatment tools for your patients with pelvic disorders and a good reminder to check the fascial mobility of the pelvic tissues.

Morrison, P., Spadt, S. K., & Goldstein, A. (2015). The Use of Specific Myofascial Release Techniques by a Physical Therapist to Treat Clitoral Phimosis and Dyspareunia. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 39(1), 17-28.