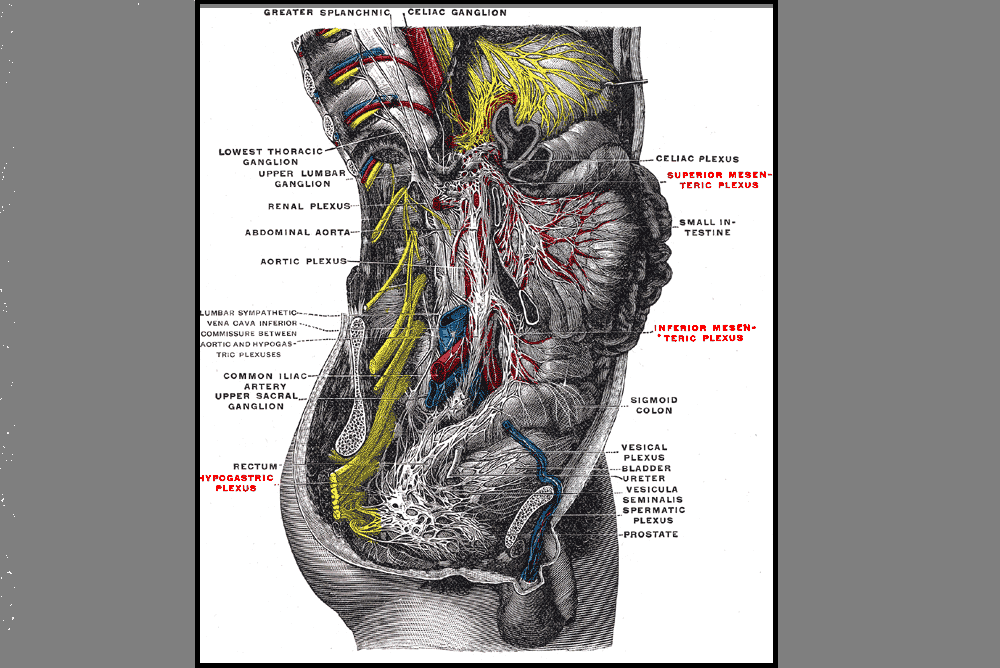

Sexual dysfunction is a common negative consequence of Multiple Sclerosis, and may be influenced by neurologic and physical changes, or by psychological changes associated with the disease progression. Because pelvic floor muscle health can contribute to sexual health, the relationship between the two has been the subject of research studies for patients with and without neurologic disease. Researchers in Brazil assessed the effects of treating sexual dysfunction with pelvic floor muscle training with or without electrical stimulation in women diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS.) Thirty women were allocated randomly into 3 treatment groups; 20 women completed the study. All participants were evaluated before and after treatment for pelvic floor muscle (PFM) function, PFM tone, flexibility of the vaginal opening, ability to relax the PFM’s, and with the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Rehabilitation interventions included pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) using surface electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback, neuromuscular electrostimulation (NMES), sham NMES, or transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS). The treatments offered to each group are shown below.

Sexual dysfunction is a common negative consequence of Multiple Sclerosis, and may be influenced by neurologic and physical changes, or by psychological changes associated with the disease progression. Because pelvic floor muscle health can contribute to sexual health, the relationship between the two has been the subject of research studies for patients with and without neurologic disease. Researchers in Brazil assessed the effects of treating sexual dysfunction with pelvic floor muscle training with or without electrical stimulation in women diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS.) Thirty women were allocated randomly into 3 treatment groups; 20 women completed the study. All participants were evaluated before and after treatment for pelvic floor muscle (PFM) function, PFM tone, flexibility of the vaginal opening, ability to relax the PFM’s, and with the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Rehabilitation interventions included pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) using surface electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback, neuromuscular electrostimulation (NMES), sham NMES, or transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS). The treatments offered to each group are shown below.

| sEMG biofeedback | Sham NMES | Intravaginal NMES | TTNS | |

| Group 1 (n=6) | X | X | ||

| Group 2 (n=7) | X | X | ||

| Group 3 (n=7) | X | X |

The following factors made up the inclusion criteria for the study: age at least 18 years, diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS, and a 4 month history of stable symptoms. All of the participants were sexually active and were found to be able to contract pelvic floor muscles correctly. Group 1 patients were treated with “sham” electrical stimulation using surface electrodes placed over the sacrum at a pulse width of 50 ms and a frequency of 2 Hz. Patients in Group 2 used an internal (vaginal) electrode at 200 ms at 10 Hz. Group 3 were given transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation at 200 ms and 10 Hz. All groups followed these treatments with pelvic floor muscle exercises using a vaginal sensor and biofeedback.

The authors concluded that pelvic floor muscle training alone or in combination with intravaginal neuromuscular electrostimulation or transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation is effective in treating sexual dysfunction in women who have MS. Improvements were noted in these groups in sexual arousal, vaginal lubrication, satisfaction, and in the Female Sexual Function Index. While the numbers in the respective intervention groups is not large enough to determine the best option for patients who have multiple sclerosis, the research reminds us that neurostimulation in conjunction with pelvic muscle training may be very valuable.

Therapists are increasingly learning about and treating pediatric patients who have pelvic floor dysfunction, yet there are still not enough of them to meet the demand. Many therapists I have spoken to are understandably concerned about how to transfer what they have done for adult patients to a younger population. Here are some of the more common concerns therapists express or questions they ask in relation to the pediatric population:

- Can we use biofeedback with children?

- Do we complete internal assessments on kids?

- How do we change the way we talk to the children?

- How much do we have to teach the parents to get the information across?

- Why do we teach strengthening even if some of the kids mostly need relaxation or coordination?

Although each question deserves a longer answer, we can start with biofeedback, and the answer is a resounding “yes”. There is abundant research affirming the potential benefit of biofeedback training for children with pelvic floor dysfunction. And no, we do not typically complete an internal pelvic muscle assessment on children, as that would not be appropriate. Considering that pediatrics can refer to young adults up to age 18-21, there may be a reasonable clinical goal in mind for utilizing internal assessment or treatment. The words we use when we speak to children become very important. Herman & Wallace faculty member Dawn Sandalcidi (known as “Miss Dawn” to her younger patients) gives ample strategies for adapting our language in her continuing education course Pediatric Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. For example, Dawn emphasizes the importance of describing an episode of incontinence as a “bladder leak” and of pointing out to a child that his or her bladder leaked, rather than the child leaking. She also likes to encourage parents and school personnel to drop the term “accident” from vocabulary. In her 2-day course, Dawn also teaches therapists how to train children to become a “Bladder Boss”, and how to teach young patients about relevant anatomy.

The way we teach anatomy to kids is really important in making sure they “get” it. One study published in 2012Equit 2013 describes the results when children are asked to draw a urinary tract in a body diagram. Only half of the children drew a bladder and other organs, and nearly 43% of the children drew “anatomically incorrect pictures.” The authors point out that older children and the ones who had gone through group training for bowel and bladder were more likely to draw correct images. For the last question about teaching contract/relax exercises to children, I had an opportunity to ask Dawn this question recently when she was filming a pediatrics course for MedBridge Education. Her answer emphasized the importance of getting children to develop awareness of the pelvic muscles, and to improve their coordination as well as strength- concepts that participating in an exercise program can work toward.

If you would like to learn more about working with children, the next opportunity to take Dawn’s course is in Boston later this month.

Equit, Monika et al. "Children's concepts of the urinary tract". Journal of Pediatric Urology , Volume 9 , Issue 5 , 648 - 652

What are you saying when giving directions to men during pelvic floor muscle training, and how do those instructions affect the effectiveness of a contraction? These questions are tackled in a study that is very interesting to therapists working in pelvic dysfunction. 15 healthy men ages 28-44 (with no prior training in pelvic floor training) were instructed to complete a submaximal effort pelvic muscle contraction. Tools utilized to acquire data in the study include those below:

| Assessment tool | Measuring |

| Transperineal ultrasound | displacement of pelvic floor landmarks |

| Surface EMG (electromyography) | abdominal, anal sphincter muscle activation |

| Nasogastric transducer | intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) |

| Fine wire electromyography (3 participants only) | puborectalis, bulbocavernosus muscles |

Participants sat upright on a plinth (backrest reclined at ~20 degrees with their knees extended). Directions for the submaximal efforts were given by telling the men to produce a level 3/10 effort with 10 being a maximal contraction. The men were instructed to hold the contraction for 3 seconds, and they were given 10 seconds rest between each of the 4 contractions using different verbal cues. (This series of 4 contractions was repeated with randomization for verbal cues, with a 2 minute rest in-between.) Verbal instructions were intended to target specific contractile tissues as described below- some of this theory could be validated via the fine wire EMG.

| Verbal cue | Targeting |

| "tighten around the anus" | anal sphincter |

| "elevate the bladder" | puborectalis |

| "shorten the penis" | striated urethral sphincter |

| "stop the flow of urine" | striated urethral sphincter, puborectalis |

Displacement, IAP, and abdominal/anal EMG were compared for the different verbal instructions. The greatest dorsal displacement of the mid-urethra and striated urethral sphincter activity was noted with the instruction to "shorten the penis." "Elevate the bladder" encouraged the greatest increase in abdominal EMG and IAP, while "tighten around the anus" induced the greatest anal sphincter activity. Displacement of pelvic landmarks correlated with EMG readings of the muscles thought to produce the targeted movement. The authors conclude that the therapist's choice of verbal instructions can influence the muscle activation and urethral movement in men. They suggest "shorten the penis" and "stop the flow of urine" for optimal activation of the striated urethral sphincter. They also point out the fact that by using the fine wire EMG and correlating muscle activation to observations with the transperineal ultrasound, the study validates the use of the less invasive method. If you are ready to jump into more education about male pelvic rehabilitation, join us in Denver in early August, or Seattle in November.

In patients who failed to respond to biofeedback therapy alone for anismus, authors in this study reported a beneficial, although temporary, effect of using botulinum toxin type A injection (BTX-A injection) to the puborectalis and external sphincter muscles. Anismus is more commonly referred to as dyssynergic defecation, or an inability to properly lengthen the pelvic floor muscles during emptying of the bowels. 31 patients who had been treated with and failed "simple biofeedback training" were then treated with BTX-A injection followed by biofeedback training. 18 males and 13 females with a mean age of 50 and a mean duration of constipation of 5.6 years were diagnosed with defecation dysfunction, or anismus. Diagnosis of animus was made using anorectal manometry, balloon expulsion test, surface electromyography (EMG) of the pelvic floor, and defecography.

Pelvic floor muscle training included biofeedback therapy consisting of intra-anal surface EMG and electrotherapy (although the way the methods are described make determining if both EMG and electrotherapy were completed with internal sensors difficult). Treatment occurred 1-2 times/day for 30 minutes per session (15 minutes of electrotherapy and 15 minutes of biofeedback). Frequency of the electrotherapy was 10 Mz, 10 seconds of "considerable sensation without…pain" and 10 seconds of rest. During biofeedback sessions, pelvic muscle strengthening and relaxation was also instructed. Therapy occurred for up to one month, and patients were instructed to continue with therapeutic exercises at home. The researchers followed up one month after the injection and therapy, and 6-12 months after intervention by telephone.

The subjects in this study suffered from difficult and incomplete evacuation, use of laxatives, and chronic straining during defecation. The repeated measures for diagnostic criteria that were completed after intervention found improvements in the subjects' resting anal canal pressures and with the balloon expulsion test and constipation scoring system. The authors also reported adverse effects of BTX-A injections including fecal incontinence. Conclusions of the article include that the botox injections were considered a temporary treatment for defecation dysfunction, whereas the botox injection combined with pelvic floor biofeedback training is "a more valid way to treat."

What is missing from this study? Manual therapy, muscle coordination retraining in combination with abdominal wall activation, and functional training related to positioning. While the authors suggest that injections should be used with biofeedback training, the potential negative effects of botox injections cannot be overlooked. Infection, pain, and bleeding are complications that have been highlighted in the literature, and in this study, fecal incontinence (although reported as mild) occurred. The research design appears to fail to recognize the chronic tension and holding pattern of the pelvic floor muscles, and unless the goal of repeated contractions is to elicit a contract/relax effect, the pelvic floor strengthening per se does not align with the ideal therapeutic goal, which should be to correct the dyssynergic pattern of defecation. Relaxing the pelvic floor muscles is not the same as a functional bearing down or lengthening of the pelvic floor involved in defecation. If you are interested in learning more about training defecation patterns and pelvic muscle rehabilitation for bowel dysfunction, check out Pelvic Floor Level 2A (PF2A) which discusses in detail fecal incontinence, constipation, and other colorectal conditions. The next opportunity to take this course is in Wisconsin in March. If you have already taken PF2A, you might find a course focused on Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction & the Pelvic Floor, with the next course taking place in Kansas City in April.