Reports in the media of research on mindfulness keep reminding us that mindfulness has positive effects on a wide variety of conditions. In the world of pelvic rehabilitation, which is broad when we consider the scope of the patient populations and diagnoses that we treat, we can find benefits from mindfulness to include bladder dysfunction, pain, and even bowel dysfunction. When specifically addressing bowel dysfunction, there are many studies that promote the benefits of mindfulness on bowel health, including the following research findings for the following topics:

Colitis

In 53 patients diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC), some were randomized into a control group or a treatment arm that consisted of instruction in mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). While mindfulness-based stress reduction did not, in this study, affect the flare-ups of patients with moderately severe ulcerative colitis, the MBSR “…had a significant positive impact on the quality of life…” when compared to patients in the control group. So even though the use of mindfulness did not appear to affect the disease, the patients utilizing mindfulness perceived a higher quality of life even during a flare of their colitis. (Jedel et al., 2014)

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

In another study, 36 people (24 diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and 12 healthy subjects in control group) were studied. The patients who had IBS were divided into equal groups and were treated with either CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) or MBT (mindfulness-based treatment.) The authors conclude that mindfulness-based therapy “…is an effective method to decrease symptoms of patients with IBS…” and that it was more effective than CBT at the 2 month follow-up. (Zomorodi et al., 2014)

Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD)

In reference to the importance of addressing mind, body and spirit for patients who have inflammatory bowel disease, this article discusses the benefits of addressing the psychosocial impacts of gastrointestinal disorders, as the disorders are “…best understood by a combination of genetic, physical, physiological, and psychological factors.” (Jedel et al., 2012)

Functional Gastrointestinal (GI) Disorders

Although a recent analysis of studies on gastrointestinal disorders calls for improvement in methodological quality of the research, the article concludes that “…mindfulness-based interventions may be useful in improving FGID [functional gastrointestinal disorders] symptom severity and quality of life with lasting effects…” (Aucoin et al., 2014)

From these few studies we can see that mindfulness is an accepted and potentially helpful adjunct in improving patient symptoms and quality of life in those who have bowel dysfunction. Mindfulness is a tool that every therapist should have in the toolbox for offering to patients who can complete this self-care activity as part of a home program. If you’d like to learn more about how to effectively instruct in mindfulness, you still have time to register for the Caroline McManus continuing education course on Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment, taking place January 16-17 in Silverdale, Washington, on the beautiful peninsula.

Aucoin, M., Lalonde-Parsi, M. J., & Cooley, K. (2014). Mindfulness-Based Therapies in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014.

Jedel, S., Hankin, V., Voigt, R. M., & Keshavarzian, A. (2012). Addressing the mind, body, and spirit in a gastrointestinal practice for inflammatory bowel disease patients. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 10(3), 244-246.

Jedel, S., Hoffman, A., Merriman, P., Swanson, B., Voigt, R., Rajan, K. B., ... & Keshavarzian, A. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to prevent flare-up in patients with inactive ulcerative colitis. Digestion, 89(2), 142-155.

Zomorodi, S., Abdi, S., & Tabatabaee, S. K. R. (2014). Comparison of long-term effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus mindfulness-based therapy on reduction of symptoms among patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from bed to bench, 7(2), 118.

If you celebrated the Thanksgiving holiday by enjoying food with family or friends, you may be lamenting the sheer amount of food you ate, or the calories that you took in. Did you know that chewing your food well can not only affect how much you eat, but also how much nutrition you derive from food? In a meta-analysis by Miquel-Kergoat et al. on the affects of chewing on several variables, researchers found that chewing affects hunger, caloric intake, and even has an impact on gut hormones. Ten papers that covered thirteen trials were included in the meta-analysis. From these trials, the following data are reported:

- 10 of 16 studies found that prolonged chewing reduced a person’s food intake

- chewing decreases self-reported hunger

- chewing decreases amount of food intake

- increasing the number of chews per bite increases gut hormone release

- chewing promotes feeling full

Research about eating behavior theories are highlighted in this paper, and include a discussion of the variety of factors, both internal and external, that control eating. Chewing is described as providing “…motor feedback to the brain related to mechanical effort…” that may influence how full a person feels when eating foods that are chewed. On the contrary, foods and beverages that do not require much chewing may be associated with overconsumption due to the lack of chewing required. (This makes sense when considering sugar-laden, high-calorie beverages.) Additionally, chewing food mixes important digestive enzymes and breaks down the food properly in the mouth, making the process of digestion further along the digestive tract more efficient. Another study by Cassady et al. which assessed differences in hunger when chewing almonds 25 versus 40 times reported that increased chewing led to decreased hunger and increased satiety when compared to chewing only 25 times.

The theory presented, yet not concluded, in this paper is that chewing may affect gut hormones and thereby decrease self-reported hunger and decrease food intake. For various reasons, including deriving more nutrition from our food, avoiding overconsumption, or making the process of digestion more efficient, focusing more on the act of chewing our food can have beneficial affects. To learn more about health and nutrition, attend the Institute’s course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist (link: https://hermanwallace.com/continuing-education-courses/nutrition-perspectives-for-the-pelvic-rehab-therapist). This continuing education course was written and instructed by Meghan Pribyl, who is not only a physical therapist who practices in pelvic rehabilitation and orthopedics, but who also has a degree in nutrition. Her training and qualifications allow her to share important information that integrates the fields of rehabilitation and nutrition. Your next opportunity to take this course is in March in Kansas City.

Cassady, B. A., Hollis, J. H., Fulford, A. D., Considine, R. V., & Mattes, R. D. (2009). Mastication of almonds: effects of lipid bioaccessibility, appetite, and hormone response. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 89(3), 794-800. Miquel-Kergoat, S., Azais-Braesco, V., Burton-Freeman, B., & Hetherington, M. M. (2015). Effects of chewing on appetite, food intake and gut hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiology & behavior, 151, 88-96.

Inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (CD), according to Lan et al., are characterized by chronic inflammation in intestinal mucosa. There is little information available based on human studies that links nutritional support with inflammatory bowel disease. The authors of this article analyzed the available information about supplements that appear beneficial in healing the gut mucosa.

The intestinal epithelium acts as a selective barrier, and inflammatory bowel disease can disrupt this important barrier, affecting absorption, mucus production, and enteroendocrine secretion. Intestinal wound healing, according to the linked article, is “dependent on the precise balance of several processes including migration, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of the epithelial cells.” Although there are few human clinical studies (more are animal and cell model studies) there is evidence that both macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies may exist in patients who have inflammatory bowel disease. Patients may have malnutrition of proteins, of minerals and vitamins. Following are some points from the article:

The intestinal epithelium acts as a selective barrier, and inflammatory bowel disease can disrupt this important barrier, affecting absorption, mucus production, and enteroendocrine secretion. Intestinal wound healing, according to the linked article, is “dependent on the precise balance of several processes including migration, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of the epithelial cells.” Although there are few human clinical studies (more are animal and cell model studies) there is evidence that both macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies may exist in patients who have inflammatory bowel disease. Patients may have malnutrition of proteins, of minerals and vitamins. Following are some points from the article:

- Arginine, glutamine, and glutamate are noted as amino acids that contribute to mucosal healing in animal studies, as well as threonine, methionine, proline, serine, and cysteine.

- Short-chain fatty acids, which are the result of metabolized dietary fiber (grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables), and resistant starch (beans, potatoes, brown rice) are a major source of energy for epithelial cells in the colon

- Vitamin A deficiency is common in patients with newly diagnosed IBD

- Vitamin D may decrease intestinal fibrosis, and reduce risk of Crohn’s relapse

- Vitamin C and Zinc may both help heal epithelial wounds in the colon

- During the remission phase, some foods may be poorly tolerated, such as dairy

- During an active flare of IBD, a patient may require enteral nutrition

The authors conclude that the exact mechanisms by which the various dietary compounds contribute to bowel healing is still unknown. Furthermore, the ability to make clear dietary recommendations is limited by the lack of clinical studies. At a minimum, this information can alert the pelvic rehab provider to discuss the potential benefits of nutrition on bowel health with patients. Many of us are quite comfortable giving advice about drinking appropriate amounts and types of fluid, or eating more whole and less processed foods. We can take our nutritional education a step further by encouraging a patient to discuss healing supplements with a provider and/or nutritionist to best support the healing bowel. If you are interested in learning more about nutrition and pelvic health, you might love our newer course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist Kansas City in March of next year with instructor Megan Pribyl.

Lan, A., Blachier, F., Benamouzig, R., Beaumont, M., Barrat, C., Coelho, D., & Tomé, D. (2015). "Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: is there a place for nutritional supplementation?" Inflammatory bowel diseases, 21(1), 198-207.

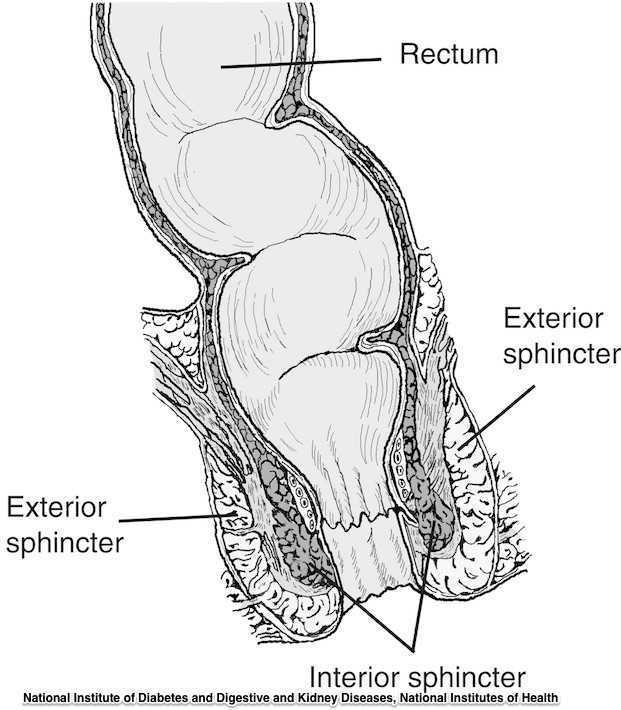

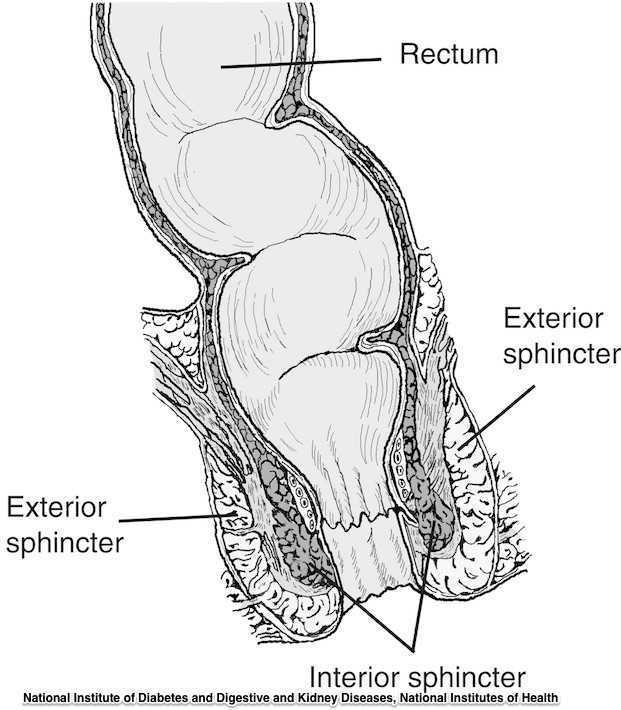

The phrase “rectal prolapse” may be easily confused with the term “rectocele” yet they may be very distinct clinical presentations. A rectocele refers to a prolapse of the posterior wall of the vagina that allows the rectum to bulge forward towards the posterior vaginal wall. This condition occurs most often in women rather than men. A rectal prolapse is a protruding of the rectum itself outside of the anal verge or opening. An overview article published in 2013 in the Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery provides information about the condition that may assist the pelvic rehabilitation provider with valuable clinical concepts. Prior to becoming a full external prolapse, an internal intussusception may occur (and observed on defecography) and progress to include an external mucosal prolapse. Rectal prolapse may occur with or without other conditions of pelvic organ descent such as a cystocele or uterine prolapse. Although the prevalence of complete rectal prolapse is low, and occurs more often in women or in elderly patients, interference with quality of life may be significant.

Symptoms can include pain, difficulty emptying the bowels, bloody and or mucous discharge, urinary incontinence, and fecal incontinence or constipation. Patients may also complain of a lump or a bulge in the rectum that may or may not improve following a bowel movement. A complete rectal prolapse can be described as a full-thickness protrusion of the rectum through the anus. A more serious consequence of this condition is strangulation of the bowel. Features of a rectal prolapse often include a redundant sigmoid colon, levator ani muscle diastasis, and loss of the vertical position of the rectum, according to the article.

Treatment of a rectal prolapse may include surgery. Prior to surgery, a physical exam, colonoscopy, anoscopy, and possibly manometry and defecography may be completed. The surgical goals are to correct the prolapse, improve any complaints of discomfort, and to resolve bowel dysfunction. Surgical approaches may include abdominal or perineal approaches, minimally invasive versus open surgery, and techniques can include posterior versus ventral and rectopexy with or without sigmoidectomy. For more details about the specific approaches for rectal prolapse repair, see the linked article. The authors of this overview article point out that because “…there is a paucity of data evaluating the effectiveness and appropriateness of the various surgical techniques…”, there is not one single management strategy for each patient.

Nonsurgical recommendations for management of a rectal prolapse include appropriate daily fluid and fiber, suppositories or enemas if needed, biofeedback training, and pelvic floor muscle exercises. A patient may benefit from education in all of these concepts, before and/or following surgery. Pelvic rehabilitation providers are well poised to offer conservative management in these conditions prior to and following any needed surgery.

To learn more about rectal prolapse and related dysfunctions, join Dr. Lila Abbate, PT, DPT, MS, OCS at Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction and the Pelvic Floor this November in New York, NY!

Visceral therapy is increasingly used by manual therapists, and research continues to emerge that attempts to explain the underlying mechanisms of the techniques. A study published in the Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies in 2012 reports on the effects of visceral therapy on pressure pain thresholds. Osteopathic visceral mobilization was applied to the sigmoid colon in 15 asymptomatic subjects. Pressure pain thresholds were measured at the L1 paraspinal muscles and 1st dorsal interossei before and after intervention. Pressure pain thresholds at the level assessed improved significantly immediately following the visceral mobilization. The effect was not found to be systemic. Hypoalgesia, therefore, may be a mechanism by which visceral mobilization affects patients who are treated with this technique.

Another research study that aimed to assess the effects of visceral manipulation (VM) on low back pain found that the addition of VM to a standard physical therapy treatment approach did not provide short term benefits. However, when the 64 patients were reassessed at 2, 6, and 52 weeks following treatment, the patients in the group with visceral manipulation were found to have less pain at 52 weeks. The patients were randomized into 2 equal groups and were provided physical therapy plus a placebo visceral treatment or a visceral treatment in addition to physical therapy. The authors propose that there may be long-term benefits of including visceral therapy in rehabilitation approaches.

If you would like to learn more about visceral techniques as well as theory and clinical application, check out the schedules for Ramona Horton's Visceral Mobilization 1 (VM1): The Urologic System, and Visceral Mobilization 2 (VM2): The Reproductive System. The first opportunity to take VM1 is in November in Salt Lake City and VM2 is scheduled in September in Ohio.

In patients who failed to respond to biofeedback therapy alone for anismus, authors in this study reported a beneficial, although temporary, effect of using botulinum toxin type A injection (BTX-A injection) to the puborectalis and external sphincter muscles. Anismus is more commonly referred to as dyssynergic defecation, or an inability to properly lengthen the pelvic floor muscles during emptying of the bowels. 31 patients who had been treated with and failed "simple biofeedback training" were then treated with BTX-A injection followed by biofeedback training. 18 males and 13 females with a mean age of 50 and a mean duration of constipation of 5.6 years were diagnosed with defecation dysfunction, or anismus. Diagnosis of animus was made using anorectal manometry, balloon expulsion test, surface electromyography (EMG) of the pelvic floor, and defecography.

Pelvic floor muscle training included biofeedback therapy consisting of intra-anal surface EMG and electrotherapy (although the way the methods are described make determining if both EMG and electrotherapy were completed with internal sensors difficult). Treatment occurred 1-2 times/day for 30 minutes per session (15 minutes of electrotherapy and 15 minutes of biofeedback). Frequency of the electrotherapy was 10 Mz, 10 seconds of "considerable sensation without…pain" and 10 seconds of rest. During biofeedback sessions, pelvic muscle strengthening and relaxation was also instructed. Therapy occurred for up to one month, and patients were instructed to continue with therapeutic exercises at home. The researchers followed up one month after the injection and therapy, and 6-12 months after intervention by telephone.

The subjects in this study suffered from difficult and incomplete evacuation, use of laxatives, and chronic straining during defecation. The repeated measures for diagnostic criteria that were completed after intervention found improvements in the subjects' resting anal canal pressures and with the balloon expulsion test and constipation scoring system. The authors also reported adverse effects of BTX-A injections including fecal incontinence. Conclusions of the article include that the botox injections were considered a temporary treatment for defecation dysfunction, whereas the botox injection combined with pelvic floor biofeedback training is "a more valid way to treat."

What is missing from this study? Manual therapy, muscle coordination retraining in combination with abdominal wall activation, and functional training related to positioning. While the authors suggest that injections should be used with biofeedback training, the potential negative effects of botox injections cannot be overlooked. Infection, pain, and bleeding are complications that have been highlighted in the literature, and in this study, fecal incontinence (although reported as mild) occurred. The research design appears to fail to recognize the chronic tension and holding pattern of the pelvic floor muscles, and unless the goal of repeated contractions is to elicit a contract/relax effect, the pelvic floor strengthening per se does not align with the ideal therapeutic goal, which should be to correct the dyssynergic pattern of defecation. Relaxing the pelvic floor muscles is not the same as a functional bearing down or lengthening of the pelvic floor involved in defecation. If you are interested in learning more about training defecation patterns and pelvic muscle rehabilitation for bowel dysfunction, check out Pelvic Floor Level 2A (PF2A) which discusses in detail fecal incontinence, constipation, and other colorectal conditions. The next opportunity to take this course is in Wisconsin in March. If you have already taken PF2A, you might find a course focused on Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction & the Pelvic Floor, with the next course taking place in Kansas City in April.

Scientists at the National University of Ireland in Maynooth reported the detection of a protein, Pellino3 that may stop Crohn's disease from developing. The Irish Times article, University breakthrough in fight against Crohn's disease, described the benefit as diagnostic: [Researchers] will now use the protein as a basis for new diagnostic for Crohn's and as a target in designing drugs to treat the illness.

Researchers noticed that levels of Pellino3 are dramatically reduced in Crohn's disease patients. Prof. Paul Moynagh, who led the researchers, believes that identifying Pellino3s role in Crohn's disease may lead to better treatments for other inflammatory bowel diseases.

In the United States, more than a half-million people suffer from Crohn's disease and more than a million suffer from some type of inflammatory bowel disease. Symptoms often include abdominal pain and diarrhea. These symptoms are often debilitating and even life-threatening. There is neither a known cause nor cure for Crohn's disease.

Therapy has been known as one of the few treatments that can reduce symptoms and even lead to remission.

Hopefully, this discovery will lead to further advancements in treating Crohn's disease: The findings by Prof Moynagh and his team have the potential to impact positively on many lives.

Erin Matlock, who struggles with ulcerative colitis, one day opened her Delzicol capsule to find her pervious medication inside.

The Bulletin, a newspaper in Central Oregon, published a piece about Matlock?s change in medication titled, ?Blocking generics.?? This piece examines the financial benefits pharmaceutical companies gain from patenting new prescriptions just before they face competition from generic manufacturers: ?With no new clinical trials, the company secured an expedited review from the FDA and got Delzicol approved six months before Asacol was due to go off-patent. ?By pulling Asacol from the market, they could get doctors to begin writing prescriptions for Delzicol and patients established on it well before a generic Asacol arrived.?

For years, Matlock took Asacol to help treat her condition.? Until it stopped being manufactured.? Her doctor told her about a new prescription from the same manufacturer called Delzicol.? Now she has the choice between taking twelve Delzicol pills (which she finds more difficult to digest) a day and spending $25 a month or taking four Apriso pills (another mesalamine-based medicine) a day while paying $125 dollars a month.

Matlock?s struggles are not uncommon.? Many patients who suffer from ulcerative colitis require medication, and even surgery, to treat their symptoms.

Although there is no known cure, correctly applied therapy has been known to markedly reduce symptoms and even lead to long-term remission.

Herman & Wallace offered their first on Bowel Pathology and Function in Stony Brook, NY last April and is in the midst of confirming dates for another course in 2014.? Keep a look out for updates!

Ulcerative Colitis (UC) dramatically effects a patient’s livelihood. UC is often confused with Crohn’s Disease, another major inflammatory bowel disease. While they do differ in origin, both diseases share similar symptoms, such as blood in a patient’s stool. Furthermore, like Crohn’s Disease, UC tends to affect young people (those between the ages of fifteen and thirty).

Chronic and often severe, UC has no known cure and, in rare cases, can even be life-threatening to the patient.

The Daily Mail posted a news article about Manchester United’s Darren Fletcher, who recently underwent his third surgery for UC. Over the last few years, Fletcher has frequently struggled to stay fit. He has played just thirteen games since December 2011.

Multiple surgeries, as in Fletcher’s case, are not uncommon. UC spreads and deeply infects the lining of a patient’s colon and rectum. Although there is no known cure, correctly applied therapy has been known to markedly reduce symptoms and even lead to long-term remission.

Herman & Wallace offered their first on Bowel Pathology and Function in Stony Brook, NY last month and is in the midst of confirming dates for another course in 2014. Keep a look out for updates!