There has been a bit of buzz on the various news outlets and social media feeds about the “new organ” the interstitium. On March 27th an article appeared in Scientific Reports, an online peer-reviewed journal from the publishers of Nature. This work was presented by a team of researchers that utilized a new in vivo laser endomicroscopy technique that demonstrated this tissue is a matrix of collagen bundles and elastic fibers surrounded by fluid rather than the tightly packed layers of connective tissue that was previously observed on fixed slides . This submucosal layer was observed in the entire gastrointestinal tract, the urinary bladder, bronchus, dermis, bronchus and peri-arterial soft tissue and fascia. The authors state, “In sum, we describe the anatomy and histology of a previously unrecognized, though widespread, macroscopic, fluid-filled space within and between tissues, a novel expansion and specification of the concept of the human interstitium” Benias et al., 2018.

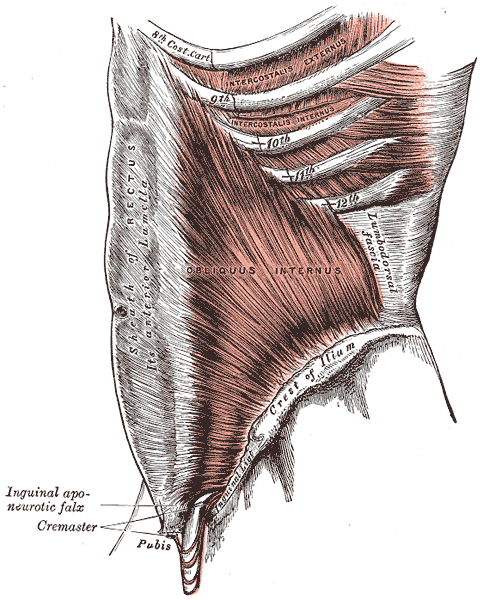

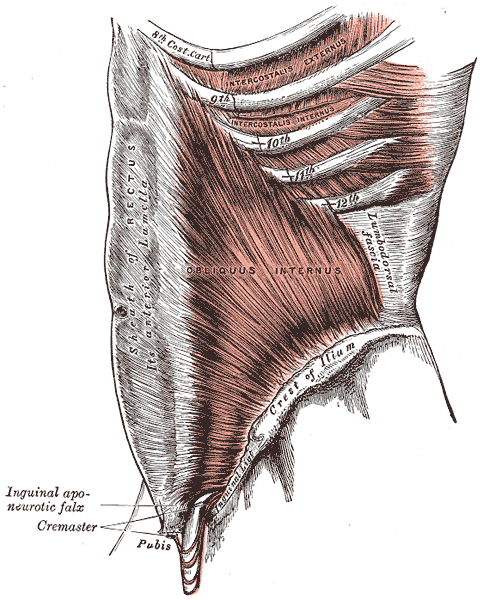

The only thing ‘new’ is the way that this group of scientists observed the tissue that until now has primarily been studied ex vivo. I find it rather humorous to note that it is mainstream news that histologists in the 21st century just realized that there is a difference in the architecture of living versus dead tissue. They noted a significant change in the appearance of tissue slides that were chemically fixed in the traditional manner when compared to studies of in vivo structures as well as fresh frozen samples. The researchers noted this tissue in the dermis as well as urinary system, gastrointestinal system and respiratory system. This further supports one of my favorite talking points presented in the visceral mobilization courses “fascia is fascia is fascia is fascia.”

The only thing ‘new’ is the way that this group of scientists observed the tissue that until now has primarily been studied ex vivo. I find it rather humorous to note that it is mainstream news that histologists in the 21st century just realized that there is a difference in the architecture of living versus dead tissue. They noted a significant change in the appearance of tissue slides that were chemically fixed in the traditional manner when compared to studies of in vivo structures as well as fresh frozen samples. The researchers noted this tissue in the dermis as well as urinary system, gastrointestinal system and respiratory system. This further supports one of my favorite talking points presented in the visceral mobilization courses “fascia is fascia is fascia is fascia.”

As an instructor that presents entire courses around the importance of the fascial system within all structures of the body including the dermis, epimysium, all organs, and the adventitia of vessels, I am thrilled to see this layer of the fascial system receive recognition and garner the attention it deserves. However, to refer to the interstitium as a new undiscovered organ is to ignore the work of the International Fascia Research Congress as well as many other notable scientists. These researchers see the fascial system as the dynamic mesenchymal tissue that unites every cell in the body and allows for fluid and tissue movement.

French hand surgeon Dr. Jean-Claude Guimrberteau has documented this tissue utilizing microendoscopy on living subjects for the past 20 years. Dr Guimberteau created a brilliant DVD called Strolling Under the Skin, you can view an excerpt available on YouTube. Following the success of several videos, he went on to co-author the book Architecture of Human Living Fascia: The extracellular matrix and cells revealed through endoscopy.

Another brilliant researcher is Orthopedic Surgeon Dr. Carla Stecco. Her paper The Fascia: the forgotten structure is an excellent review of the three-dimensional continuity of the myofascia. Following multiple publications, she also authored the book The Functional Atlas of the Human Fascial System. Her work is limited to the myofascial layer and does not include the visceral fascia although she notes its presence in her published works. For those that would like to know more about this tissue, I highly recommend both of these authors. If you wish to explore how a physical therapist can utilize this information in clinical practice, join me for one of my courses on fascial manipulation. The fascial based treatment for pelvic dysfunction series includes:

- Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremity

- Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Gastrointestinal System

- Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Reproductive System of Men and Women

Benias, P. C., Wells, R. G., Sackey-Aboagye, B., Klavan, H., Reidy, J., Buonocore, D., ... & Theise, N. D. (2018). Structure and Distribution of an Unrecognized Interstitium in Human Tissues. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 4947. https://:doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23062-6, 2018.

Stecco, C., Macchi, V., Porzionato, A., Duparc, F., & De Caro, R. (2011). The fascia: the forgotten structure. Italian journal of anatomy and embryology, 116(3), 127.

My manual therapist husband once wrote a paper on the visceral referral pattern of the liver. Although he knows I injured my right shoulder shoveling snow a few years ago, whenever I have an exacerbation of shoulder pain, he likes to joke it is from my liver. (I would laugh if I had not acquired an affinity for red wine since having kids!) Sometimes pain in remote areas of our body really can be related to an organ in distress or simply “stuck” because of fascial restrictions around it. The kidneys in particular can refer pain into the low back and hips, and the bladder and ureters can provoke saddle area pain.

Tozzi, Bongiorno, and Vitturini (2012) looked into the kidney mobility of patients with low back pain. They used real-time Ultrasound to assess renal mobility before and after osteopathic fascial manipulation (OFM) via the Still Technique and Fascial Unwinding. The experimental group receiving OFM consisted of 109 people, and the control group receiving a sham treatment had 31 people, all with non-specific low back pain. For comparison, 101 subjects without back pain were also assessed with the ultrasound to determine a mean Kidney Mobility Score (KMS). The landmarks for measuring the renal mobility were the superior renal pole of the right kidney and the pillar of the right diaphragm, and they subtracted the distance at maximal inspiration (RdI) from that of maximal expiration (RdE). A significant difference was found in the KMS scores of asymptomatic versus symptomatic subjects with low back pain. Pre and post-RD values of the experimental group were significantly different from the control group. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire also demonstrated significant differences in the experimental versus control groups. The results of the study revealed a correlation between decreased renal mobility and non-specific low back pain and showed an improvement in renal mobility and low back pain after an osteopathic manipulation.

In 2016, Navot and Kalichman presented a case study of a 32 year old professional male cyclist with right hip and groin pain after an accident that caused a severe hip contusion and tearing of the tensor fascia latae and the gluteus medius muscles. A few rounds of physical therapy gave him partial relief of his pain in sitting and with cycling, and his hip range of motion only improved slightly. Despite no complaints of pelvic floor dysfunction, he was evaluated for involvement of the pelvic floor musculature and fascia. Pelvic Floor Fascial Mobilization was performed for 2 sessions, and the cyclist’s symptoms resolved completely. This case implied the efficacy of manual fascial release of the pelvic floor to reduce hip and groin pain.

When something seemingly orthopedic in nature does not respond with full resolution of symptoms from traditional physical therapy, the source of the pain may be deeper. Often times, we just need to ask the right questions to uncork the mystery of why a pain is lingering. No matter how skilled we are with our techniques, if we are not reaching the area in need, we are wasting our effort and our patients’ time and money. “Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System” is a course that provides a practitioner with the extra insight and tools to address potential sources of unresolved symptoms of low back, hip, and groin pain.

Tozzi, P., Bongiorno, D., and Vitturini, C. (2012) Low back pain and kidney mobility: local osteopathic fascial manipulation decreases pain perception and improves renal mobility. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 16(3):381-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.02.001

Navot, S and Kalichman, L. (2016). Hip and groin pain in a cyclist resolved after performing a pelvic floor fascial mobilization. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 20(3):604-9. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.04.005

“…visceral manual therapy can produce immediate hypoalgesia in somatic structures segmentally related to the organ being mobilized…”

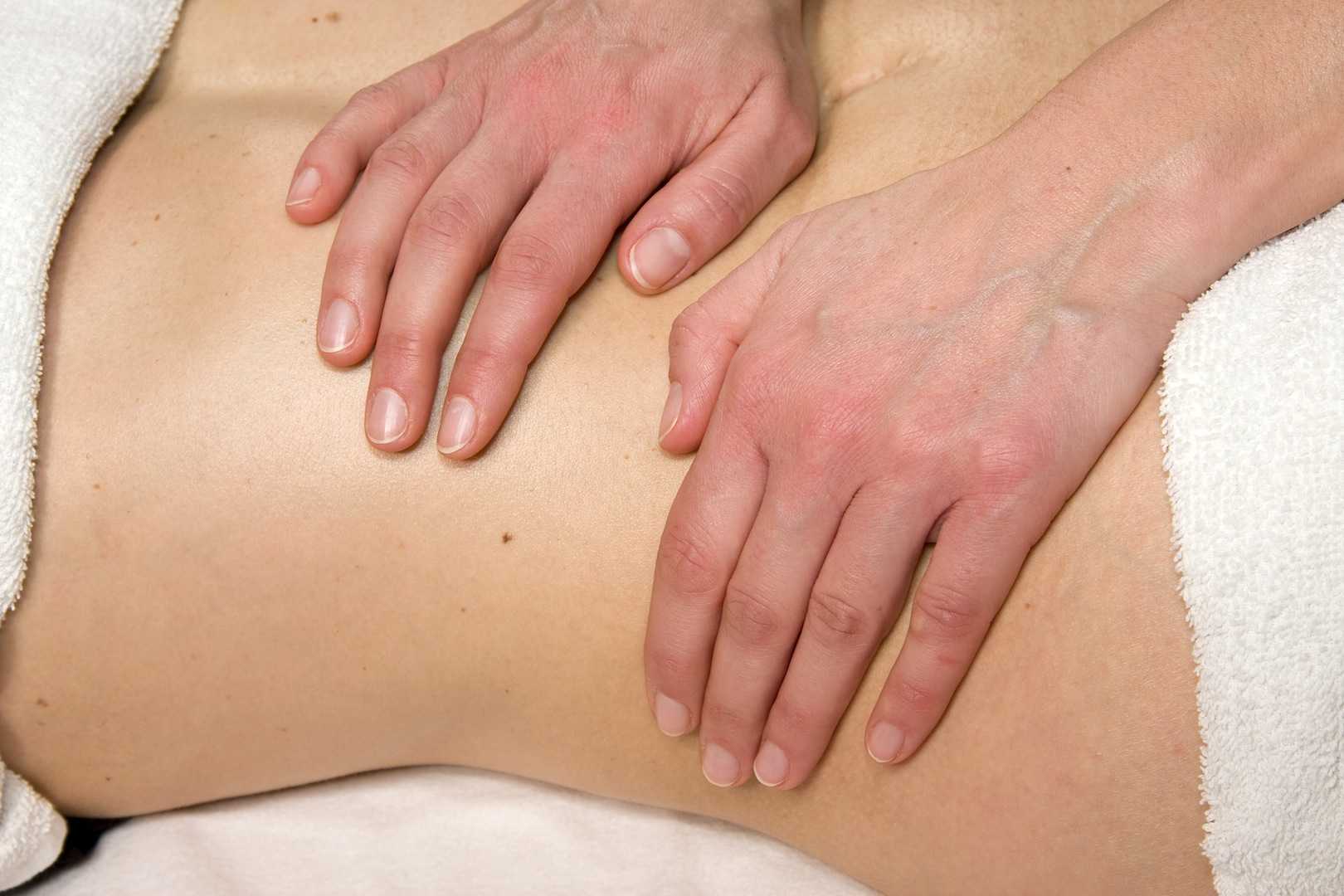

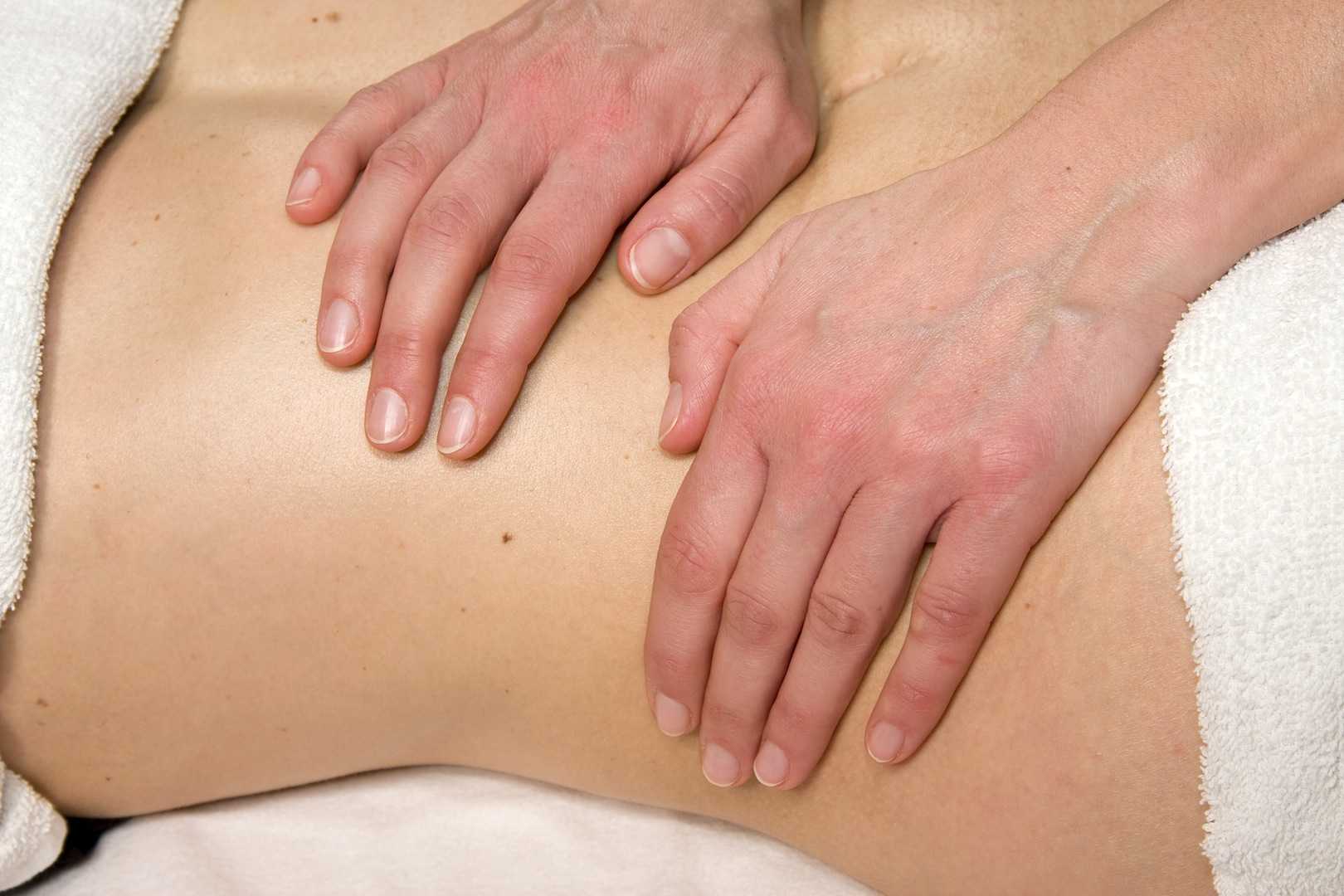

This statement is taken from an article written by MCSweeney and colleagues published in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies in 2012. The authors, who state that there is a lack of research that explains underlying mechanisms for visceral mobilization, aimed to determine if visceral mobilization could produce local and/or systemic effects towards hypoalgesia. The measurement of hypoalgesia, defined by the IASP as “diminished pain in response to a normally painful stimulus,” was assessed by use of a hand-held manual digital pressure algometer for pressure pain threshold (PPT). Sixteen asymptomatic subjects were recruited from an osteopathic school and were treated on separate occasions with a visceral mobilization of the sigmoid colon, a sham intervention of manual contact on the abdomen, and a control of no intervention. Six females (mean age 23.7) and ten males (mean age 27.7) completed the single-blinded, randomized study.

The clinical practice relevance was difficult to determine, however, this study used new techniques to determine that there is an immediate and measurable effect on the body. While therapists who treat with visceral mobilization and other soft tissue techniques know that the interventions have helped their patients, having further experimental and clinical validation of the value of these techniques is critical. If you are interested in learning more about fascial approaches to easing pain and improving function in your patients, check out the courses offered by faculty member Ramona Horton.

Ramona will be teaching her Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremities course three times this year, with the next event in Nashua, NH June 3-5. Her Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System course is available three times as well, next in Kirkland, WA on June 24-26. If you're ready for the advanced course, and some wine tasting(!), check out Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Reproductive System of Men and Women on October 14-16 in Medford, OR.

McSweeney, T. P., Thomson, O. P., & Johnston, R. (2012). The immediate effects of sigmoid colon manipulation on pressure pain thresholds in the lumbar spine. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies, 16(4), 416-423.

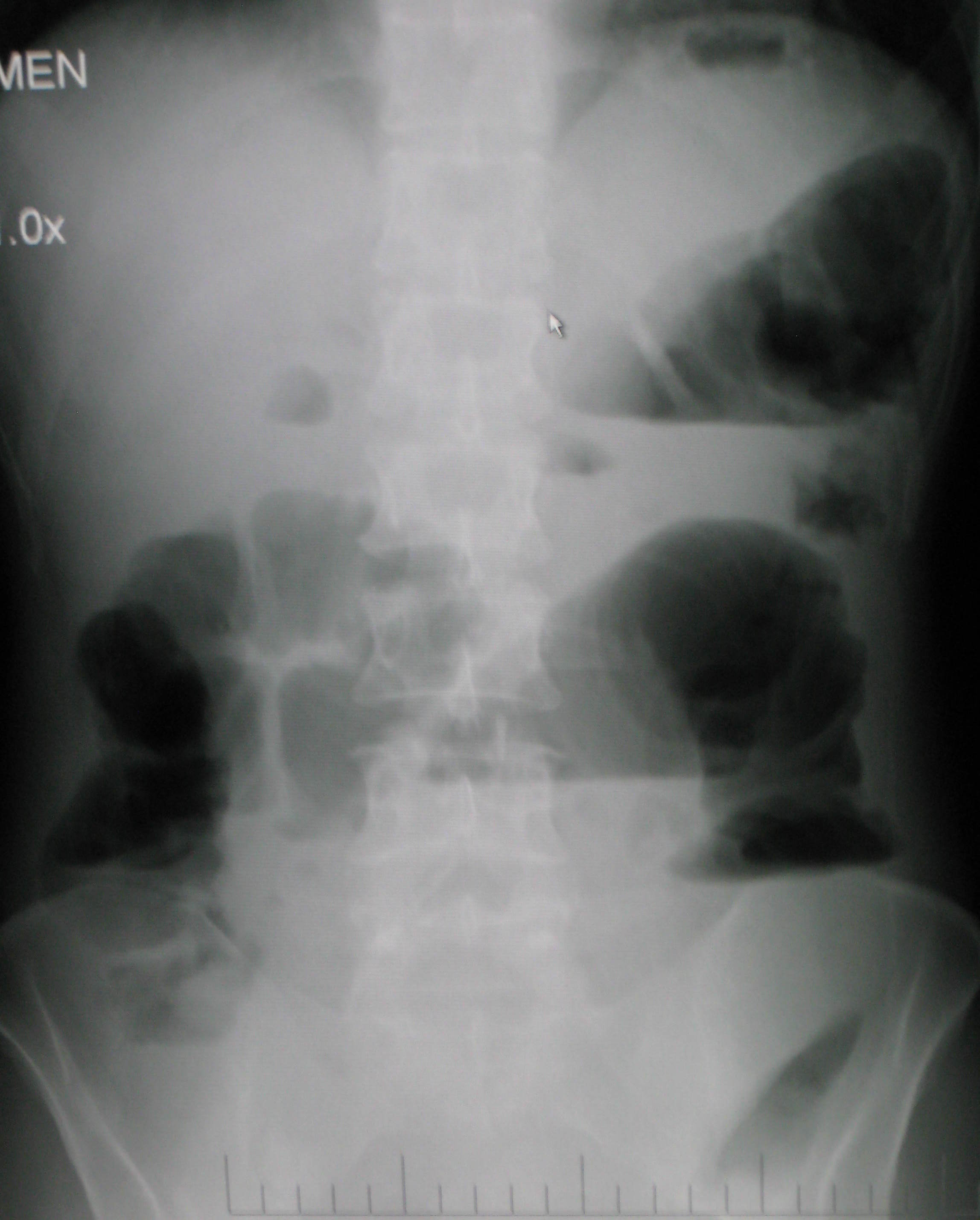

If an infomercial played in pre-op waiting rooms explaining all the possible side effects or problems a patient may encounter after surgery, I wonder how many people would abort their scheduled mission. As if having an abdominal or pelvic surgery were not enough for a patient to handle, some unfortunate folks wind up with small bowel obstruction as a consequence of scar tissue forming after the procedure. Instead of having yet another surgery to get rid of the obstruction, which, in turn, could cause more scar tissue issues, studies are showing manual therapy, including visceral manipulation, to be effective in treating adhesion-induced small bowel obstruction.

Amanda Rice and colleagues published a paper in 2013 on the non-surgical, manual therapy approach to resolve small bowel obstruction (SBO) caused by adhesions as evidenced in two case reports. One patient was a 69 year old male who had 3 hernia repairs and a laparotomy for SBO with resultant abdominal scarring and 10/10 pain on the visual analog scale. The other patient was a 49 year old female who endured 7 abdominopelvic surgeries for various issues over the course of 30 months and presented with 7/10 pain and did not want more surgical intervention for SBO. Both patients received 20 hours of intensive manual physical therapy over a period of 5 days. The primary focus was to reduce adhesions in the bowel and abdominal wall for improved visceral mobility, but treatment also addressed range of motion, flexibility, and postural strength. The female patient reported 90% improvement in symptoms, with significant decreases in pain during bowel movements or sexual intercourse, and the therapist noted increased visceral and myofascial mobility. Both patients were able to avoid further abdominopelvic surgery for SBO, and both patients were still doing well at a one year follow up.

Amanda Rice and colleagues published a paper in 2013 on the non-surgical, manual therapy approach to resolve small bowel obstruction (SBO) caused by adhesions as evidenced in two case reports. One patient was a 69 year old male who had 3 hernia repairs and a laparotomy for SBO with resultant abdominal scarring and 10/10 pain on the visual analog scale. The other patient was a 49 year old female who endured 7 abdominopelvic surgeries for various issues over the course of 30 months and presented with 7/10 pain and did not want more surgical intervention for SBO. Both patients received 20 hours of intensive manual physical therapy over a period of 5 days. The primary focus was to reduce adhesions in the bowel and abdominal wall for improved visceral mobility, but treatment also addressed range of motion, flexibility, and postural strength. The female patient reported 90% improvement in symptoms, with significant decreases in pain during bowel movements or sexual intercourse, and the therapist noted increased visceral and myofascial mobility. Both patients were able to avoid further abdominopelvic surgery for SBO, and both patients were still doing well at a one year follow up.

In 2016, a prospective, controlled survey based study by Rice et al., determined the efficacy of treating SBO with a manual therapy approach referred to as Clear Passage Approach (CPA). The 27 subjects enrolled in the study received this manual therapy treatment for 4 hours, 5 days per week. The CPA includes techniques to increase tissue and organ mobility and release adhesions. The therapist applied varying degrees of pressure across adhered bands of tissue, including myofascial release, the Wurn Technique for interstitial spaces, and visceral manipulation. The force used and the time spent on each area were based on patient tolerance. The SBO Questionnaire considered 6 domains (diet, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, medication, quality of life, and pain severity) and was completed by 26 of the subjects pre-treatment and 90 days after treatment. The results revealed significant improvements in pain severity, overall pain, and quality of life. Suggestive improvements were noted in gastrointestinal symptoms as well as tissue and organ mobility via improvement in trunk extension, rotation, and side bending after treatment. Overall, the authors conclude the manual therapy treatment of SBO is a safe and effective non-invasive approach to use, even for the pediatric population with SBO.

Myofascial release and visceral manipulation can disrupt the vicious cycle of adhesions causing small bowel obstruction after abdominopelvic surgical “invasion.” Learning specific techniques we may never have thought of can make a huge impact on certain patient populations. Quality of life for our patients often depends on how willing we are to increase our own knowledge and skill base.

Rice, A. D., King, R., Reed, E. D., Patterson, K., Wurn, B. F., & Wurn, L. J. (2013). Manual Physical Therapy for Non-Surgical Treatment of Adhesion-Related Small Bowel Obstructions: Two Case Reports . Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2(1), 1–12. PubMed Link

Rice, A. D., Patterson, K., Reed, E. D., Wurn, B. F., Klingenberg, B., King, C. R., & Wurn, L. J. (2016). Treating Small Bowel Obstruction with a Manual Physical Therapy: A Prospective Efficacy Study. BioMed Research International, 2016, 7610387. http://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7610387

Today we are fortunate to hear from Barbara S. Rabin MSPT ATC PYTc, owner and practitioner at Holistic Physical Therapy in Gates Mills, OH. Barbara has more than 20 years of experience in orthopedic rehabilitation. Her perspective as an athletic trainer and orthopedic therapist highlights the many approaches practitioners can take when working with pelvic rehabilitation patients.

"We were reminded how all the muscles of the hip are intricately integrated into the pelvic floor and one can’t ignore the influence and interaction they have on each other."

My physical therapy career has been in the world of outpatient orthopedics and sports medicine. While in physical therapy graduate school I became a nationally certified athletic trainer, and most of my post graduate CEU’s have been in the orthopedic and sports medicine arena.

Stepping Outside the Comfort Zone

As an orthopedic PT, it was “safe” to study the pelvic girdle when I took Richard Jackson’s continuing education course in 1994 because it focused on muscles, ligaments, bones and nerves. However, I was leaving “safe territory” when I took Janet Hulme’s course, “Beyond Kegels: Evaluation and Treatment of Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction and Incontinence” in 1998. Long ago, back in gross anatomy lab in physical therapy school, we barely looked at the pelvic floor contents. Yes, we identified the digestive system but basically ignored all of the rest. Our mission was mostly to learn the muscles, ligaments, bones and nerves. After Janet Hulme’s course, I tried to offer incontinence rehabilitation at my place of employment at the time, but the idea was quickly dismissed. However, I am very glad to say that pelvic floor rehab is now commonly offered at most major hospitals and many clinics.

I continued my education of the pelvis and hip in several other courses and especially enjoyed one I attended last year called, "Extra-Articular Pelvic and Hip Labrum Injury: Differential Diagnosis and Integrative Management" by the Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute and taught by Ginger Garner PT ATC PYT. We were reminded how all the muscles of the hip are intricately integrated into the pelvic floor and one can’t ignore the influence and interaction they have on each other.

I was intrigued and wanted to learn more about the pelvic floor. I got another opportunity when I most recently attended an intimidating course for an “orthopedic sports medicine physical therapist” called, “Mobilization of Visceral Fascia for the Treatment of Pelvic Dysfunction - Level 1: The Urinary System” taught by Ramona Horton, MPT. I learned that externally mobilizing the bladder can often increase hip extension. Here was a combining of the fascial, pelvic floor, and orthopedic worlds!

Myofascial Release and Other Manual Therapy

I learned several manual therapy techniques in courses, and I took the best out of many but never specialized. As of late, I have been gladly drawn into the world of John F Barnes myofasical release. Studying and working with the fascia coincides with my holistic approach of rehabilitation, since the fascia is intricately woven throughout our body. The fascia was another thing we ignored in gross anatomy lab in physical therapy school. It was cut to move it out of the way so we could “get to the important stuff.” Even in that dead and embalmed state, the fascia was fascinating. It was strong and flexible at the same time. Now, with the advent of micro discography of the fascia by Dr. Jean-Claude Guimberteau (http://www.guimberteau-jc-md.com/en/biographie.php) we can view fascia in its live state and we can really see the phenomenal structure that it truly is.

Incorporating Yoga into Rehabilitation Practices

About eight years ago I took my first yoga class. I thought I was a conditioned athlete as a lifelong runner but I was humbled as I could not even balance on one leg for a minute. I noticed the physical and emotional benefits in myself and wanted to include yoga in the treatment of my patients. I had a patient who had physical issues from an eating disorder and needed supervision to exercise. I thought to myself that what she needed was not physical therapy but possibly meditation and relaxation. Even though I didn’t learn those techniques in PT school, I felt that I should be able to offer them to my patients. With one yoga class under my belt, in 2007, I entered into a 200 hour teacher training with Marni Task studying her combination of Jivamukti and Anusara yoga. I further continued my yoga training in 2011 with Ginger Garner PT, ATC, PYT of Professional Yoga Therapy Studies (http://proyogatherapy.org). Her school of medical yoga training, was just what I was looking for to merge my worlds of physical therapy and yoga.

Instead of looking at our patients as “pieces and parts,” referring to them as “the knee or the shoulder patient,” it is so important to see them as a whole. As an orthopedic PT I need to recognize that patients have not only a physical side of muscles, ligaments, bones and nerves, but other parts too that make them a whole person. Most likely I won’t specialize in pelvic pain or woman’s health but it is so important for me to be knowledgeable about this field to be the most effective therapist. In addition, it’s important to also go beyond the physical aspect and recognize patient’s psycho-emotional-social, spiritual, energetic, and intellectual aspects of their beings. Optimal health is achieved by recognizing and addressing all aspects of a patient.

And on that note, I’m going to continue merging all of my worlds of fascia, pelvic floor, orthopedics, and yoga, to address all the components of well-being, as I attend an upcoming course offered by Herman and Wallace called, Yoga for Pelvic Pain this month in Cleveland, Ohio.

Visceral therapy is increasingly used by manual therapists, and research continues to emerge that attempts to explain the underlying mechanisms of the techniques. A study published in the Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies in 2012 reports on the effects of visceral therapy on pressure pain thresholds. Osteopathic visceral mobilization was applied to the sigmoid colon in 15 asymptomatic subjects. Pressure pain thresholds were measured at the L1 paraspinal muscles and 1st dorsal interossei before and after intervention. Pressure pain thresholds at the level assessed improved significantly immediately following the visceral mobilization. The effect was not found to be systemic. Hypoalgesia, therefore, may be a mechanism by which visceral mobilization affects patients who are treated with this technique.

Another research study that aimed to assess the effects of visceral manipulation (VM) on low back pain found that the addition of VM to a standard physical therapy treatment approach did not provide short term benefits. However, when the 64 patients were reassessed at 2, 6, and 52 weeks following treatment, the patients in the group with visceral manipulation were found to have less pain at 52 weeks. The patients were randomized into 2 equal groups and were provided physical therapy plus a placebo visceral treatment or a visceral treatment in addition to physical therapy. The authors propose that there may be long-term benefits of including visceral therapy in rehabilitation approaches.

If you would like to learn more about visceral techniques as well as theory and clinical application, check out the schedules for Ramona Horton's Visceral Mobilization 1 (VM1): The Urologic System, and Visceral Mobilization 2 (VM2): The Reproductive System. The first opportunity to take VM1 is in November in Salt Lake City and VM2 is scheduled in September in Ohio.

The following post was contributed by Herman & Wallace faculty member Ramona Horton. Ramona teaches three courses for the Institute; "Myofascial Release for Pelvic Dysfunction", "Mobilization of Visceral Fascia for the Treatment of Pelvic Dysfunction - Level 1: The Urologic System", and "Mobilization of Visceral Fascia for the Treatment of Pelvic Dysfunction - Level 2: The Reproductive System". Join her at Visceral Mobilization of the Urologic System - Madison, WI on June 5-7!

My physical therapy training and initial experience were in the US Army, so I had a strong bias toward utilization of manual therapy techniques based on a structural evaluation. When the birth of my 10 pound baby boy threw me head-long into the desire to become a pelvic dysfunction practitioner, I became plagued by the question: how do you treat the bowel and bladder, without treating the bowel and bladder? That, along with a mild obsession for the study of anatomy was the genesis of my desire to explore the technique of visceral mobilization.

The field of pelvic physical therapy has moved far beyond the rehabilitation of the pelvic floor muscles for the purpose of gaining continence, which was its origin. Now pelvic rehabilitation is a comprehensive specialty within the PT profession, treating a variety of populations and conditions (Haslam & Laycock 2015). Research has provided a greater understanding of the abdomino-pelvic canister as a functional and anatomical construct based on the somatic structures of the abdominal cavity and pelvic basin that work synergistically to support the midline of the body. The canister is bounded by the respiratory diaphragm and crura, along with the psoas muscle whose fascia intimately blends with the pelvic floor and the obturator internus and lastly the transversus abdominis muscle (Lee et al. 2008). The walls of this canister are occupied by and intimately connected to the visceral structures found within. These midline contents carry a significant mass within the body. In order for the canister to move, the viscera must be able to move as well, not only in relationship to one another, but with respect to their surrounding container. There are three primary mechanisms by which disruption of these sliding surfaces could contribute to pain and dysfunction: visceral referred pain, central sensitization and changes in local tissue dynamics.

Since the inception of physical therapy, manual manipulation of tissues has been a foundational practice within the profession. Manual therapy is a generic therapeutic category for hands-on treatment of a structural anomaly; it encompasses a variety of techniques which can be subdivided into either soft tissue based or joint based. Although the majority of manual therapy research has been on the musculoskeletal system, its effects are not exclusive to any particular region of the anatomy. The Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) defines the technique of mobilization as "the act of imparting movement, actively or passively, to a joint or soft tissue" (Farrell & Jensen 1992). Visceral mobilization is a treatment approach focusing on mobilizing the fascial layer of the visceral system with respect to the somatic frame; it therefore falls under the classification of soft tissue based manual therapies. Soft tissue and or fascial based manual therapies have higher-levels of evidence to support their use for treating musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction (Ajimsha & Al-Mudahka 2014; Gay et al. 2013). Although many models have been proposed, the specific mechanisms behind the response of the musculoskeletal system to manual interventions are still not fully understood (Bialosky et al. 2009; Clark & Thomas 2012).

The previous model of manual therapy directly relieving local tissue provocation has given way to a recognition that the observed clinical improvement is not simply a result of the practitioner directly altering the structure beneath their hands through mechanical means. Rather this improvement is a combination of afferent input influencing the neurophysiologic output, changes in the endogenous cannabinoid system, and even a placebo responses simply because of touch (Bialosky et al. 2009; McParland 2008; Gay et al. 2014).

There is significant clinical evidence that issues of somatic pelvic pain, bowel, bladder and reproductive system dysfunction may be the result of visceral referred pain, central sensitization and restrictions in visceral tissue mobility which may further contribute to dysfunction within the canister of core muscles. The musculoskeletal framework is a mysterious, perplexing and complicated system. It is unique in that it offers us a variety of tissues and techniques from which to choose in order to help our patients from a manual therapy perspective. Science has acknowledged that the visceral structures and their connective tissue attachments indeed have an influence on the function of the somatic frame, the question is can we manually manipulate these structures and bring about an effect with a reasonable degree of specificity while producing a therapeutic outcome.

Part 2 of this report will discuss the evidence to support visceral mobilization.

Ajimsha M.S., Al-Mudahka N.R. & Al-Madzhar J.A. (2015) Effectiveness of myofascial release: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 19, 102-112.

Clark B.C., Thomas, J.S., Walkowski S., Howell J.N. (2012) The biology of manual therapies. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 112 (9), 617-29.

Bialosky J., Bishop M. & Price D. (2009) The mechanisms of manual therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain: a comprehensive model. Manual Therapy 14 (5), 531-538.

Gay C.W., Robinson M.E., George S.Z., Perlstein W.M. & Bishop M.D. (2014) Immediate changes after manual therapy in resting-state functional connectivity as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging in participants with induced low back pain. Journal of Manipulative and Physiologic Therapeutics 37 (6), 614-627.

Haslam J. & Laycock J. (2015) How did we get here? The development of women’s health physiotherapy special interest groups in the UK. Journal of Pelvic Obstetric and Gynecological Physiotherapy 116 (Spring), 15-24.

Farrell J.P. & Jensen G.M. (1992) Manual therapy: a critical assessment of role in the profession of physical therapy. Physical Therapy 72, 843-852.

Lee D.G., Lee L.J. & McLaughlin L. (2008) Stability, continence and breathing: The role of fascia following pregnancy and delivery. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 12 (4), 333-348.

McPartland J M (2008) Expression of the endocannabinoid system in fibroblasts and myofascial tissues. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 12(2), 169-182.