Unfortunately one of the most common things we hear in pelvic rehab is “I hope you can help me, you’re my last hope.” In severe cases, this translates to the patient having little hope of surviving their life with pelvic pain. In severe but not necessarily life-threatening cases, being a patient’s last hope can also mean “please help me have sex in my relationship or my partner is going to leave me.” This situation places a lot of pressure on the patient and also on the therapist. How long did it take this patient to find her way to pelvic rehab? Research tells us that most women have been through multiple physicians, under- or misdiagnosed, and that many have failed attempts at intervention with medications or procedures.

It’s clear to women that they are being judged when they go to medical appointments complaining of pelvic pain or pain with intercourse. Although it seems really old school to hear that a provider said “It’s all in your head.” or “How much do you like your partner?” or “Well, you’re getting older, sex isn’t that important.” these dismissive phrases are still used. A study by Nguyen et al., 2013 reported that women who reported chronic pain were more likely to perceive being stereotyped by doctors and others. Interestingly, among the group of women who had chronic vulvar pain, the women who sought care for their condition reported feeling more stigmatized. Because the support a woman perceives may influence her willingness to seek out help for chronic vulvar pain, we need to keep educating our peers, the public, and the providers about the real challenges women face, and the power of rehabilitation in overcoming those challenges.

It’s clear to women that they are being judged when they go to medical appointments complaining of pelvic pain or pain with intercourse. Although it seems really old school to hear that a provider said “It’s all in your head.” or “How much do you like your partner?” or “Well, you’re getting older, sex isn’t that important.” these dismissive phrases are still used. A study by Nguyen et al., 2013 reported that women who reported chronic pain were more likely to perceive being stereotyped by doctors and others. Interestingly, among the group of women who had chronic vulvar pain, the women who sought care for their condition reported feeling more stigmatized. Because the support a woman perceives may influence her willingness to seek out help for chronic vulvar pain, we need to keep educating our peers, the public, and the providers about the real challenges women face, and the power of rehabilitation in overcoming those challenges.

Vulvodynia is a common pelvic pain condition, and one that typically is associated with painful intercourse, or dyspareunia. (Arnold et al., 2006) It's estimated that by the age of 40, as many as 8% of women will have or have had a diagnosis of vulvodynia (Harlow et al., 2014), and this is clearly a significant quality of life issue.

Physical therapy has been shown to be successful in treating vulvar pain and pain with intercourse, including as part of a multidisciplinary approach. (Brotto et al., 2015) That's why Herman & Wallace is so eager to help empower more therapists to help patients live a life free of vulvar pain and dyspareunia. You can learn more about our courses and other resources at https://www.hermanwallace.com/continuing-education-courses.

Arnold, L. D., Bachmann, G. A., Kelly, S., Rosen, R., & Rhoads, G. G. (2006). Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with co-morbidities and quality of life. Obstetrics and gynecology, 107(3), 617.

Brotto, L. A., Yong, P., Smith, K. B., & Sadownik, L. A. (2015). Impact of a multidisciplinary vulvodynia program on sexual functioning and dyspareunia. The journal of sexual medicine, 12(1), 238-247.

Harlow, B. L., Kunitz, C. G., Nguyen, R. H., Rydell, S. A., Turner, R. M., & MacLehose, R. F. (2014). Prevalence of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia: population-based estimates from 2 geographic regions. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 210(1), 40-e1.

Nguyen, R. H., Turner, R. M., Rydell, S. A., MacLehose, R. F., & Harlow, B. L. (2013). Perceived stereotyping and seeking care for chronic vulvar pain. Pain Medicine, 14(10), 1461-1467.

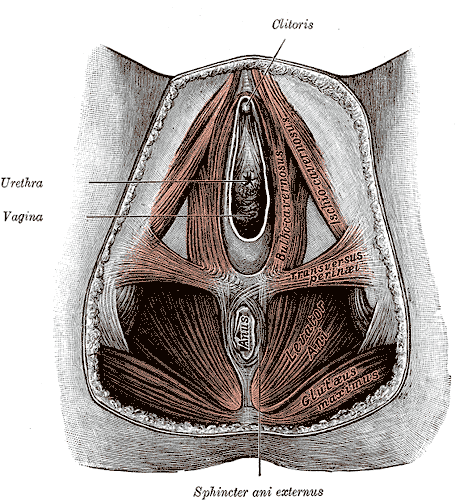

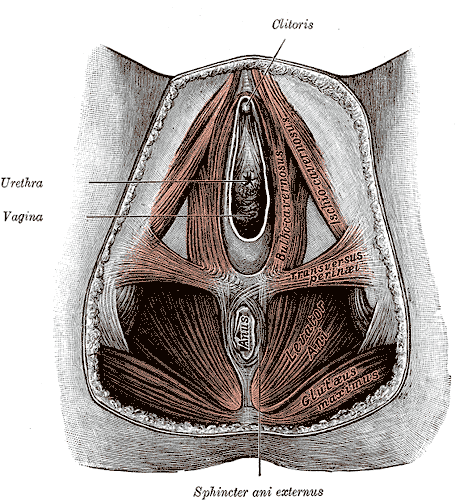

Episiotomy is defined as an incision in the perineum and vagina to allow for sufficient clearance during birth. The concept of episiotomy with vaginal birth has been used since the mid to late 1700’s and started to become more popular in the United States in the early 1900’s. Episiotomy was routinely used and very common in approximately 25% of all vaginal births in the United States in 2004. However, in 2006, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended against use of routine episiotomies due to the increased risk of perineal laceration injuries, incontinence, and pelvic pain. With this being said, there is much debate about their use and if there is any need at all to complete episiotomy with vaginal birth.

What are the negative outcomes of episiotomy?

What are the negative outcomes of episiotomy?

The primary risks are severe perineal laceration injuries, bowel or bladder incontinence, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and pelvic floor laxity. Use of a midline episiotomy and use of forceps are associated with severe perineal laceration injury. However, mediolateral episiotomies have been indicated as an independent risk factor for 3rd and 4th degree perineal tears. If episiotomy is used, research indicates that a correctly angled (60 degrees from midline) mediolateral incision is preferred to protect from tearing into the external anal sphincter, and potentially increasing likelihood for anal incontinence.

What are the indications for episiotomy, if any?

This remains controversial. Some argue that episiotomies may be necessary to facilitate difficult child birth situations or to avoid severe maternal lacerations. Examples of when episiotomy may be used could include shoulder dystocia (a dangerous childbirth emergency where the head is delivered but the anterior shoulder is unable to pass by the pubic symphysis and can result in fetal demise.), rigid perineum, prolonged second stage of delivery with non reassuring fetal heart rate, and instrumented delivery.

On the other side of the fence, many advocate never using an episiotomy due to the previously stated outcomes leading to perineal and pelvic floor morbidity. In a recent cohort study in 2015 by Amorim et al., the question of “is it possible to never perform episiotomy with vaginal birth?” was explored. 400 women who had vaginal deliveries were assessed following birth for perineum condition and care satisfaction. During the birth there was a strict no episiotomy policy and Valsalva, direct pushing, and fundal pressure were avoided, and perineal massage and warm compresses were used. In this study there were no women who sustained 3rd or 4th degree perineal tears and 56% of the women had completely intact perineum. 96% of the women in the study responded that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their care. The authors concluded that it is possible to reach a rate of no episiotomies needed, which could result in reduced need for suturing, decreased severe perineal lacerations, and a high frequency of intact perineum’s following vaginal delivery.

Are episiotomies actually being performed less routinely since the 2006 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendation?

Yes, a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association by Friedman, it showed that the routine use of episiotomy with vaginal birth has declined over time likely reflecting an adoption of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations. This is ideal, as it remains well established that episiotomy should not be used routinely. However, indications for episiotomy use remain to be established. Currently, physicians use clinical judgement to decide if episiotomy is indicated in specific fetal-maternal situations. If one does receive an episiotomy then a mediolateral incision is preferred. The World Health Organization’s stance is that an acceptable global rate for the use of episiotomy is 10% or less of vaginal births. So the question still remains, (and of course more research is needed) to episiotomy or not to episiotomy?

Amorim, M. M., Franca-Neto, A. H., Leal, N. V., Melo, F. O., Maia, S. B., & Alves, J. N. (2014). Is It Possible to Never Perform Episiotomy During Vaginal Delivery?. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 123, 38S.

Friedman, A. M., Ananth, C. V., Prendergast, E., D’Alton, M. E., & Wright, J. D. (2015). Variation in and Factors Associated With Use of Episiotomy. JAMA, 313(2), 197-199.

Levine, E. M., Bannon, K., Fernandez, C. M., & Locher, S. (2015). Impact of Episiotomy at Vaginal Delivery. J Preg Child Health, 2(181), 2.

Melo, I., Katz, L., Coutinho, I., & Amorim, M. M. (2014). Selective episiotomy vs. implementation of a non episiotomy protocol: a randomized clinical trial. Reproductive health, 11(1), 66.

How often do we hear of patients trying to explain their sexual pain to a partner, only to be doubted, not believed, or guilt tripped into having sex because of the lack of understanding of the condition? I’d say about as often as we hear of the other unfortunate misunderstandings about the nature of painful sexual function, such as people not wanting to be in a relationship for fear of sexual dysfunction limiting their participation, or believing that healthy sex is gone for good. Most of us are familiar with the phrase, “not tonight- I’ve got a headache” yet how often is the truth really that a person has a “pelvic ache?” And do headaches and pelvic pain go together? That is the question posed in research published in the journal Headache.

For 72 women who were being treated for chronic headache, a survey was administered to assess for associations between sexual pain and libido, a history of abuse, and to determine the number of women being treated for sexual pain. Nearly 71% of the women were diagnosed on the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD)-III criteria with chronic migraines, nearly 17% with medication overuse headache, 10% with both chronic overuse headache and migraine. Below are some of the statistics from the survey.

For 72 women who were being treated for chronic headache, a survey was administered to assess for associations between sexual pain and libido, a history of abuse, and to determine the number of women being treated for sexual pain. Nearly 71% of the women were diagnosed on the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD)-III criteria with chronic migraines, nearly 17% with medication overuse headache, 10% with both chronic overuse headache and migraine. Below are some of the statistics from the survey.

| Symptom | % Respondents who Experienced Symptom |

| Pelvic region pain brought on by sexual activity | 44% |

| Pelvic region pain preventing from engaging in sexual activity | 18% |

| Among women who had pain: | |

| Reported pain for < 1 year | 3% |

| Reported pain for 1-5 years | 35% |

| Reported pain for 6-10 years | 29% |

| Reported pain for > 10 years | 32% |

Although the next statistics should not be so surprising based on prior literature and on our work in the clinics, 50% of the women had not discussed their pelvic pain with a provider. Of the women who had discussed their pelvic pain with a provider, 37.5% were currently receiving treatment, 31% had not received any treatment, 31% had received care in the past, and 1% did not provide an answer. Reasons for not receiving treatment included that no treatment was offered, pain was not severe enough to warrant care, or fear of pursuing treatment due to embarrassment. Unfortunately, rehabilitation was not a significant part of the treatment plan, even though all but one of the women said they would want to pursue care if available.

Other interesting associations were made in the article, which is available as full text in the link above, including rates of sexual abuse, and associations between types of headaches and pelvic pain. The bottom line is that headaches and pelvic pain can occur together, and that based on this research, many women are still suffering for long periods of time without accessing care for pelvic pain. When it comes to headaches, there are many types of headaches, and many other conditions that occur and can cause pain in the head, face, and neck. If you would like to sharpen your clinical tools related to headaches, as well as dizziness and vertigo, you still have time to sign up for the Institute’s new continuing education course on Neck Pain, Headaches, Dizziness, and Vertigo that takes place in Rockville in November.

The research on pelvic pain and specifically on sexual dysfunction has focused on heterosexual women, leaving a large gap in the clinically-based evidence. A study published last year in the Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy aimed to narrow this gap by studying the characteristics of vulvar pain in women in a variety of relationships. The associations between qualities such as love and communication were evaluated in relation to the participants' perceptions of how pain influenced their relationships. Within the research report, the authors establish that pelvic pain commonly causes pain and limitation with sexual function, and that queer women (defined in their work as women who identify as something other than heterosexual) also experience pain with sexual function.

"Of the 839 women, 31% reported genital pain, with 12% of the women with genital pain in a same-sex relationship, 67% in a mixed-sex relationship, and 21% being single"

The women in the study provided information about demographics, experiences of genital pain and pain characteristics. They completed surveys including the Dyadic Trust Scale (measures trust in a close relationship), the Rubin Love Scale (assesses level of romantic love), and the Communication Subscale of Evaluation and Nurturing Relationship Issues, Communication and Happiness Marital Satisfaction Scale (measures level of communication). Participants' average age was 25, and of the 77% who were in a relationship, most (60%) were in a mixed-sex relationship. Average length of relationships was 3 years, with nearly 84% of the women being white with some level of higher education.

Of the 839 women, 31% reported genital pain, with 12% of the women with genital pain in a same-sex relationship, 67% in a mixed-sex relationship, and 21% being single. Of the 260 women reporting genital pain, 39% identified as heterosexual, 15% identified as lesbian, and 46% identified as bisexual. The most common pain locations reported were inside the vagina (48%), in the pelvis or abdomen (45%), at the vaginal opening (39%), and 21% of the women reported global vulvar pain. From the data, the authors also report that women in same-sex relationships were likely to report that tampon insertion was painful.

The authors point out that challenges to healing for women who identify outside of heterosexual are many, and can include:

- homonegativity and heterosexism at a medical provider's office

- failure to disclose sexual identity due to fear of negative interaction

- fear that a symptom is linked to a sexual practice

- being in an unsupportive relationship or having poor adjustment within relationship

The limited research on sexual pain in women in same sex relationships has highlighted strengths within the relationships as well. Women in same sex relationships have been noted to have more effective communications skills, which may in turn foster better understanding of conditions such as pelvic pain. The authors concluded that while the characteristics of vulvar pain were similar across groups, there was a difference in the perception of pain impact on relationships. Better communication for same-sex couples and more love for mixed-sex couples was positively associated with impact on relationship. Of the women reporting pain, nearly half of the participants indicated that the pain negatively impacted their relationship in general, and 64% reported that the pain interfered with sexual health.

This type of research provides insight for pelvic rehabilitation clinicians and adds to our data base of considerations when working with women. The truth is that most of us were not provided adequate training in how to evaluate and manage issues of sexual health, nor were we provided with the means to value our own sexuality as a normal and healthy part of being. This lack requires education to fill in our own gaps, so that we can be of best service to our patients. If we are able to be present and nonjudgmental, our patients can in turn share openly and provide information that can direct best care. Holly Herman, co-founder of the Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute, offers a 2-day course in Sexual Medicine, so that providers can learn more about healthy sexuality as well as how to dialog with our patients.

Today we get the opportunity to hear from Herman & Wallace faculty member Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCIA-PMB! Elizabeth has been kind enough to offer her insights about the diagnosis of pelvic rehabilitation patients. Join Elizabeth at Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain this November in Houston, TX in order to learn evaluation tools for complex pelvic pain clients!

Having taught for Herman and Wallace since 2006, I have a few observations that have been consistent over the years. Clinicians want their clients to get better, so much so that they are ready to jump in to treatment before having a solid problem list and validated findings. I can understand this: after a 3 day course we have clients Monday morning at 8 a.m. who have been waiting for us to take this course so we can get them better! We had better be smart ASAP! But what do we do when we are treating symptoms rather than understanding the primary, secondary and tertiary factors in their condition?

Having taught for Herman and Wallace since 2006, I have a few observations that have been consistent over the years. Clinicians want their clients to get better, so much so that they are ready to jump in to treatment before having a solid problem list and validated findings. I can understand this: after a 3 day course we have clients Monday morning at 8 a.m. who have been waiting for us to take this course so we can get them better! We had better be smart ASAP! But what do we do when we are treating symptoms rather than understanding the primary, secondary and tertiary factors in their condition?

Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain is a course that is a foundational first step in screening the pelvic pain client. It is a great place to start. I developed the course because there was no evidence based comprehensive factors that had been established as fundamentals for screening a pelvic pain client.

The other thing I have learned after teaching Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, & Treatment – Level 2B for 9 years is that the majority of clinicians who take this intermediate level course cannot perform a precise vulvar and intrapelvic muscle mapping assessment. Close your eyes and pretend you are mapping a client’s left iliococcygeus: can you place your finger in the proper orientation and know 100% you would be palpating it? Indeed, this takes training and repetition. Internal pelvic floor muscle mapping is a key part of the Finding the Driver screening system.

What do you do when you have a pelvic pain client on your schedule and a 45-60 minute slot? How do you screen findings and get the plan of care within such a short period of time? Finding the Driver is a comprehensive pelvic floor and musculoskeletal screening to rule in or rule out drivers of the pain from all sources including spine, pelvic ring, neural entrapment, intra-articular hip, load transfer, biomechanics and motor control. There is a clear flow to the screening process and an emphasis on how to organize that information, as we know with pelvic pain, it is the copious amount of information that is the challenge. We have two case studies with either participants or clients of a local Physical Therapist who come in and we go through the entire screen, prioritize treatment and provide that treatment during the course. The participants walk away with clear clinical reasoning for their treatment and prioritization of treatment as primary, secondary, and so on. The goal of the course is to help the clinician sort through the extraordinary amount of information we gather on our pelvic pain client and organize it in a way that we can explain to the client as well as create our plan of care. Treatment is not linear, as we are frequently treating many aspects at the same time. However being able to organize the information is key in designing that plan of care. For example, with a prone knee bend that reproduces labial pain, we find that the genitofemoral nerve is causing referred pain. However that referral may be due to constipation, irritable bowel, inguinal entrapment due to hernia surgery, intra-abdominal adhesions due to endometriosis, osteitis pubis or facilitated segment at the upper lumbar spine. How do we tease that out? How do you sequence nerve glide, visceral work, soft tissue mobilization, joint mobilization and dietary components for colonic motility? The treatment with all of those components are very different indeed. Finding the Driver is a hands on course with systematic screening tools and, with case studies, we go through treatments appropriate to that client. The focus is on what we, as physical therapists, can do to understand the drivers.

At the last Finding the Driver course in Milwaukee, WI, we had two case studies in pelvic pain. One client reported chronic psoas and adductor tightness with deep left sided pelvic pain. As a professional aerialist, she was extraordinarily flexible and demonstrated positions of tightness that concerned her, which included lateral splits with her hips in slight horizontal abduction and extension (yes, yikes!) When she reported that her adductor felt tight in this position, I explained it was because it was trying to keep her leg attached to her body! She was 9/9 on the Beighton scale and had severe multidirectional instability in her hips, impaired load transfer through her pelvis, respiratory dysfunction with efforts at pelvic floor and transverse abdominis contraction, as well as repeated choice of activities that were profoundly provoking. Interestingly, she was better at load transfer during handstands (bilateral or unilateral) vs. in standing and we discussed her course of treatment addressing the primary, secondary and tertiary aspects of her condition. Another client had severe labial pain, and despite multiple abdominal and intravaginal surgeries, her symptom onset was 4 months prior. She certainly had visceral, postural, joint restrictions, movement dysfunction and many other factors. But her primary driver was a labral tear in her hip and she needed surgery. After surgery, her pain was 100% resolved and in her post op rehab, the other factors could be addressed.

It is safe to say that it can be difficult to perform a comprehensive screen in 45-60 minutes on ALL clients. We all know that many of our clients need to tell their story and because of fear or previous negative history, we may choose as clinicians how to spend that session to best honor the needs of the client. That being said, Finding the Driver is a course which provides a solid start in differential diagnosis so you can drill down into more specifics on subsequent visits.

Many diagnoses that live under the umbrella of "chronic pelvic pain" have similar symptoms, confounding the differential diagnosis and development of a treatment pathway. Dr. Charles Butrick, in an article published in 2007, suggested that gynecologists "…be alert to…interstitial cystitis in patients who present with chronic pelvic pain typical of endometriosis." The concurrent conditions of bladder pain syndrome (BPS) and endometriosis have been described as "evil twins syndrome" in the realm of chronic pelvic pain. Bladder pain syndrome. also known as Interstitial Cystitis (IC), is a condition commonly associated with pelvic pain, bladder pressure, and urinary dysfunction such as urgency and frequency. Endometriosis can also cause or contribute to pelvic pain, and a variety of pelvic dysfunctions including bowel, bladder, or sexual dysfunction.

A study published in the International Journal of Surgery reported on the prevalence of these two conditions. Utilizing a systematic review approach, the authors located articles reporting on the prevalence of bladder pain syndrome and endometriosis in women with chronic pelvic pain. Nine observational studies were included, and the range of endometriosis diagnosis ranged from 11%-97%, with a mean prevalence of 61%. The prevalence of endometriosis ranged from 28%-93% with a mean prevalence of 70%. The large variation in these rates were explained as potentially being due to the variations in study quality and sample selection. (The authors point out that the highest rates of prevalence for BPS and endometriosis were noted in the patient groups recruited from specialist clinics and from lists of patients from operating lists.) The study concludes that in women who present with chronic pelvic pain (CPP), screening for bladder pain syndrome is important so that appropriate treatment can be directed to all issues.

If another chronic pelvic pain condition, pudendal neuralgia, is added to the diagnoses of endometriosis and painful bladder syndrome, "evil triplet syndrome" can be experienced by a patient. The various symptoms of each of these conditions can add to the total level of pain and dysfunction experienced by a woman with chronic pelvic pain. Having the tools to evaluate and treat symptomatology and address the chronic aspect of tissue, joint, neural, myofascial, and the processing of pain is a skill that most pelvic rehabilitation therapists continue to work on throughout their careers. Michelle Lyons, faculty member from Ireland, brings her "Special Topics in Women's Health" course to Chicago in a couple of weeks. Within the course, Michelle will be discussing each of these conditions from the standpoint of a multidisciplinary approach, and with the role of the pelvic rehabilitation provider in mind. She will also be sharing up-to-date and practical information about infertility and hysterectomy. If you are interested in joining Michelle and colleagues in Chicago, you still have time to sign up! And if you would like to host Michelle's course in your facility, give us a call or send us a note!

This post was written by Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCIA-PMB, who teaches the course Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain: Musculoskeletal Factors in Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. You can catch Elizabeth teaching this course in April in Milwaukee.

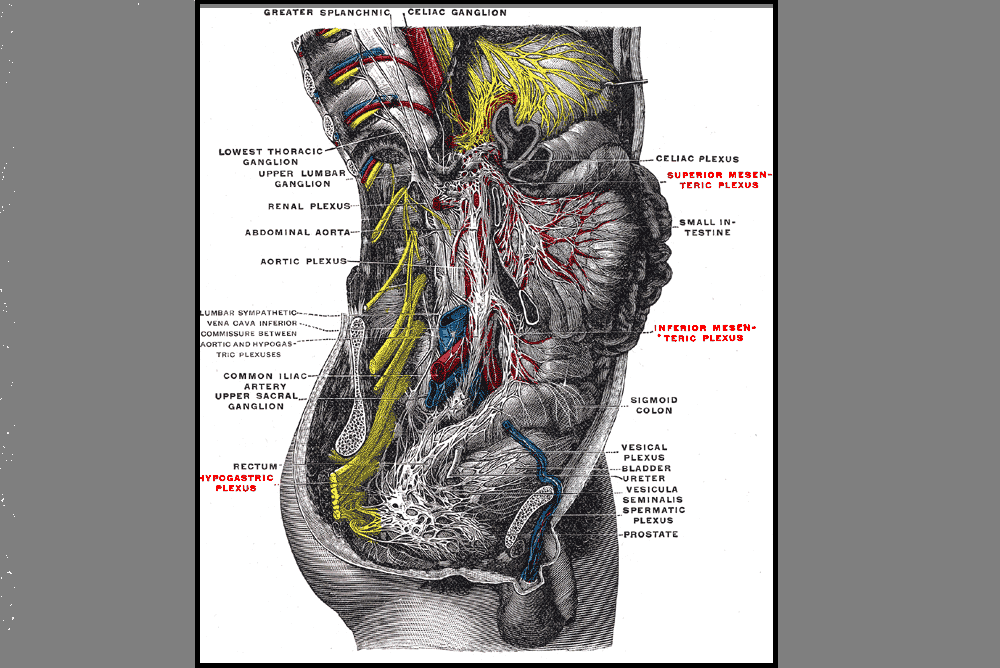

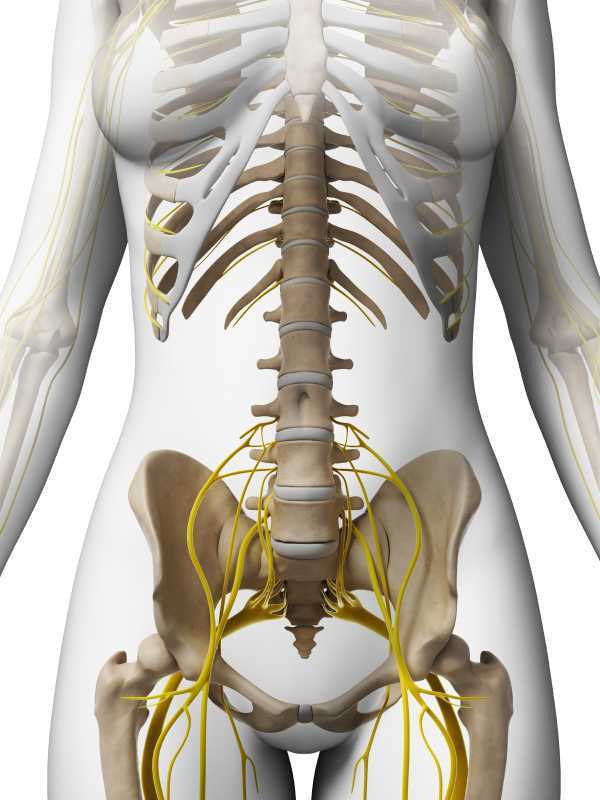

Chronic pelvic pain has multifactorial etiology, which may include urogynecologic, colorectal, gastrointestinal, sexual, neuropsychiatric, neurological and musculoskeletal disorders. (Biasi et al 2014) Herman and Wallace faculty member, Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCB-PMD has developed an evidence based systematic screen for pelvic pain that she presents in her course “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain”. One possible origin of pelvic pain as well as chronic psoas pain and hypertonus may arise from genitofemoral, ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric neuralgia, the screening of which is addressed in the “Finding the Driver” extrapelvic exam.

The iliohypogastric nerve arises from the anterior ramus of the L1 spinal nerve and is contributed to by the subcostal nerve arising from T12. This sensory nerve travels laterally through the psoas major and quadratus lumborum deep to the kidneys, piercing the transverse abdominis and dividing into the lateral and anterior cutaneous branches between the TVA and internal oblique. The anterior cutaneous branch provides suprapubic sensation and the lateral cutaneous branch provides sensation to the superiolateral gluteal area, lateral to the area innervated by the superior cluneal nerve. (10)

The ilioinguinal nerve arises from the L1 spinal levels, passes through the psoas major inferior to the iliohypogastric nerve, across the quadratus lumborum and iliacus and lastly through the transversus abdominis along with the iliohypogastric nerve between the transverse abdominis and the internal oblique muscle. (7) The ilioinguinal nerve supplies the skin of the medial thigh, upper part of the scrotum/labia as well as penile root (5).

The genitofemoral nerve arises from the L1 and L2 spinal levels and splits into the genital and femoral branches after passing through the psoas muscle. (1). The genital branch (motor and sensory) passes through the inguinal canal and innervates the upper area of the scrotum of men. In women it runs alongside the round ligament and innervates the area of the skin of the mons pubis and labia majora. The motor function of the genital branch is associated with the cremasteric reflex. The femoral (sensory) branch runs alongside the external iliac artery, through the inguinal canal and innervates the skin of the upper anterior thigh. (8)

Differential diagnosis of entrapment of one of the three nerves can be challenging due to their overlapping sensory innervations and anatomic variability. Rab et al found up to 4 different patterns of anatomical variability in these nerve pathways. (9)

Transient or lasting genitofemoral, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgia results from compression or irritation of these nerves anywhere along their pathway: from their spinal origin to distal pathways. Cesmebasi at al report that “neuropathy can result in paresthesias, burning pain, and hypoalgesia associated with the nerve distributions. “ (11) These entrapments may be associated with surgery, T12-L2 segmental dysfunction or HNP, constipation and is commonly observed clinically alongside psoas overactivity and pain. Lichtenstein found that up groin pain after hernia surgery ranged from 6-29% with Bischoff et al (2012) (6) denoting the post-operative neuralgia ranging from 5-10%.

Differential diagnosis of nerve entrapments are key skills in the screening of musculoskeletal contributing factors to pelvic pain and physical therapists are uniquely skilled to put all of the puzzle pieces together in these complex clients. Finding the Driver is being offered twice in 2015: April 23-25, 2015 at Marquette University and again in the fall. Check Herman & Wallace's webite for further details.

http://www.gotpaindocs.com/gentfmrl_nurlga.htm

Tubbs et al.Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. March 2005 / Vol. 2 / No. 3 / Pages 335-338. Anatomical landmarks for the lumbar plexus on the posterior abdominal wall. http://thejns.org/doi/abs/10.3171/spi.2005.2.3.0335

Phillips EH. Surgical Endoscopy. January 1995, Volume 9, Issue 1, pp 16-21. Incidence of complications following laparoscopic hernioplasty

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00268-012-1657-2

Tsu W et al. World Journal of Surgery. October 2012, Volume 36, Issue 10, pp 2311-2319. Preservation Versus Division of Ilioinguinal Nerve on Open Mesh Repair of Inguinal Hernia: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Bischoff JM. Hernia. October 2012, Volume 16, Issue 5, pp 573-577. Does nerve identification during open inguinal herniorrhaphy reduce the risk of nerve damage and persistent pain?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilioinguinal_nerve

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genitofemoral_nerve

Rab M, Ebmer And J, Dellon AL.. Anatomic variability of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve: implications for the treatment of groin pain.

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery [2001, 108(6):1618-1623].

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cutaneous_innervation_of_the_lower_limbs

Cesmebasi et al (2014) Genitofemoral neuralgia: A review. Clinical Anatomy. Volume 28, Issue 1, pages 128–135, January 2015. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ca.22481/abstract

This post was written by H&W instructor Elizabeth Hampton. Elizabeth will be presenting her Finding the Driver course in Milwaukee in April!

One of the most consistent questions that we hear at the Pelvic Floor 2B course is, “How do you choose between a pelvic floor and a musculoskeletal exam during your first visit with a pelvic pain client?” The answer depends on a number of factors, which include your clinical reasoning, toolbox, the client’s presentation, the clinical specialty, and expectations of the referring provider as well as the expectations of the client. It can be stressful to imagine gathering a detailed history, testing, client education and a home program within the first visit! Now that we have less time and total visits to evaluate and treat these complex issues, it can be overwhelming to know where to start.

Chronic pelvic pain has multifactorial etiology, which may include urogynecologic, colorectal, gastrointestinal, sexual, neuropsychiatric, neurological and musculoskeletal disorders. (Biasi et al 2014) Herman and Wallace faculty member, Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCB-PMD has developed an evidence based systematic screen for pelvic pain that she presents in her course “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain”. “There are a number of extraordinary models that exist for treatment of pelvic pain including Diane Lee’s Integrated System of Function, Postural Restoration Institute, Institute of Physical Art and more,” states Hampton. “However, regardless of the treatment style and expertise of the clinician, each clinician should be able to perform fundamental tissue specific screening. If a client has L45 discogenic LBP with segmental hypermobility into extension, femoral acetabular impingement, urinary frequency > 12/day as well as constipation contributed to by puborectalis functional and structural shortness, all clinicians should be able to arrive at the same fundamental findings during their screening exam. The driver of the PFM overactivity(3) needs to be explored further as local treatment alone (biofeedback and downtraining) will not resolve until the condition causing the hypertonus is found and treated.” Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain is a course that models a comprehensive intrapelvic and extrapelvic screening exam with evidence based validated testing to rule out red flags, understand key factors in the client’s case as well as develop clinical reasoning for prioritizing treatment and plan of care. The screening exam complements any treatment model as it identifies tissue specific pain generators and structural condition, which will lead the clinician to follow their clinical reasoning and treatment model. Once the fundamentals are established, the clinician can move beyond screening and drill down into treatment of key factors which may include specific muscle gripping patterns, arthokinematic assessment and respiratory evaluation and retraining, among others.

Co-morbidities are common in pelvic pain are well documented (1, 2) and clinically these multiple factors are the reason pelvic pain is complex to evaluate and treat. Intrapelvic (urogynecologic, colorectal, sexual) as well as extrapelvic (orthopedic, neurologic, psychological and biomechanical clinical expertise) are required for skilled evaluation and treatment of this population. It is precisely this complexity, which makes working with pelvic pain clients challenging and extraordinarily rewarding. Physical therapists are uniquely skilled to put all of the puzzle pieces together in these complex clients. Finding the Driver is being offered twice in 2015: April 23-25, 2015 at Marquette University and again in the fall. Check Herman Wallace.com for further details.

1. Chronic pelvic pain: comorbidity between chronic musculoskeletal pain and vulvodynia. Reumatismo: 2014 6;66(1):87-91. Epub 2014 Jun 6. G Biasi, V Di Sabatino, A Ghizzani, M Galeazzi

2. http://www.jhasim.net/files/articlefiles/pdf/XASIM_Master_5_6_p306_315.pdf

3. IUGA/ICS Terminology for Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.iuga.org/resource/resmgr/iuga_documents/iugaics_termdysfunction.pdf