Emily McElrath, PT, DPT, MTC, CIDN is instructing her upcoming course Pregnancy & Postpartum Considerations For High Intensity Athletics scheduled on May 21, 2023. This one-day remote continuing education course is designed to educate practitioners on the unique considerations of pregnant and postpartum athletes engaging in high intensity interval training (HIIT).

Emily is a native of New Orleans and received her undergraduate degree in Athletic Training at the University of Southern Mississippi and went on to receive her Doctorate of Physical Therapy from the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences. She is highly trained in Sports and Orthopedics and has a passion for helping women achieve optimal sports performance. Emily is certified in manual therapy and dry needling, which allows her to provide a wide range of treatment skills including joint and soft tissue mobilization. She is an avid runner and Cross-fitter and has personal experience modifying these activities during pregnancy and postpartum.

Introduction: Although routine exercise has long been recommended throughout pregnancy by medical professionals, High Intensity Athletics like Crossfit, weightlifting, and HIIT have received mixed approval amongst healthcare providers. There seems to be limited knowledge on how this form of exercise affects the pelvic floor and abdominal wall throughout pregnancy and postpartum, thus creating a limited understanding of proper recommendations by healthcare providers in regard to how and when a patient can safely continue and/or return to high intensity athletics during pregnancy and postpartum. Unfortunately, some (likely well-intended) medical professionals have gone so far as to instruct their patients to completely avoid these types of exercise throughout pregnancy. But are these limitations really necessary? Does the research support these recommendations? Or is there a way we can help these women continue to safely participate in high intensity athletics throughout pregnancy, and return appropriately in the postpartum phase?

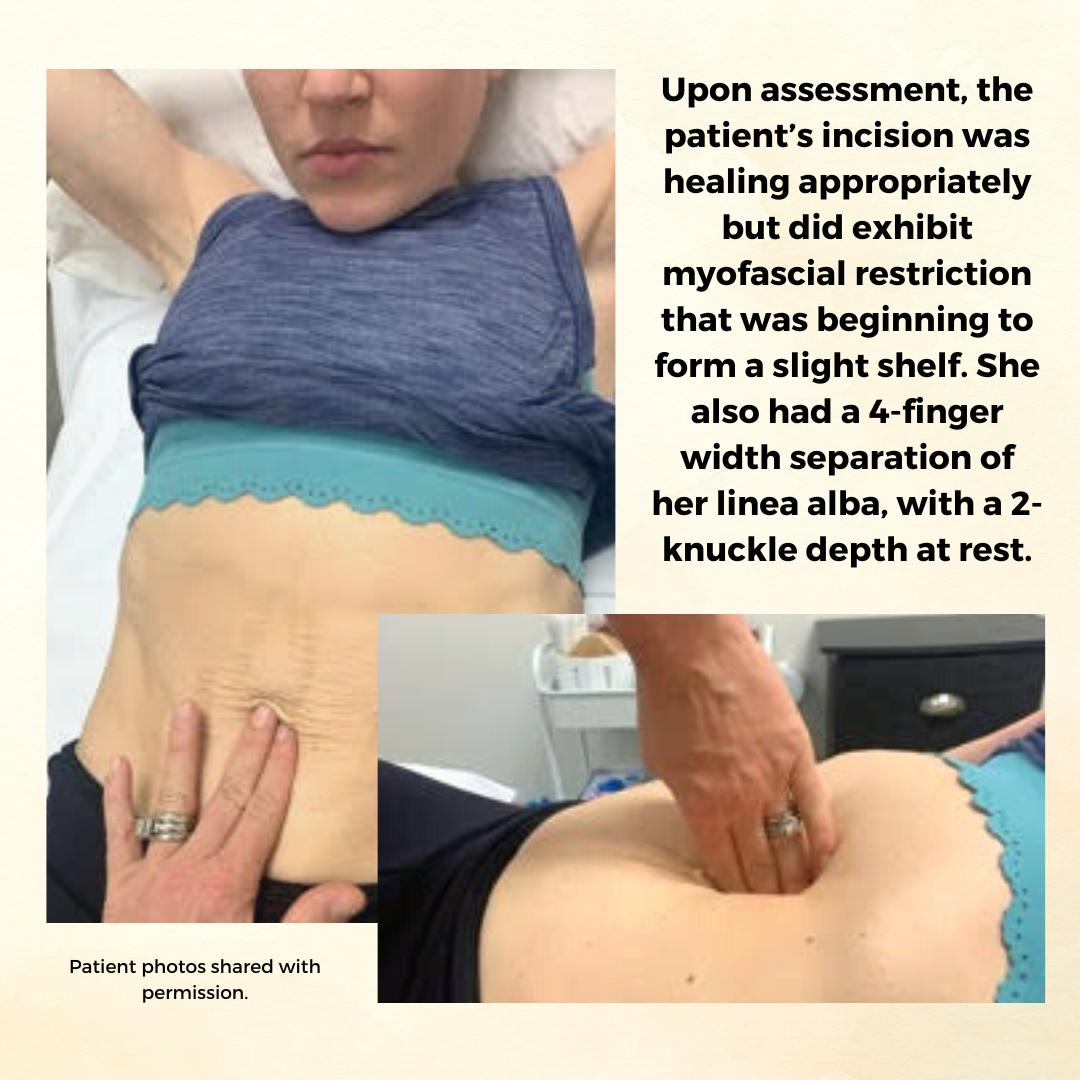

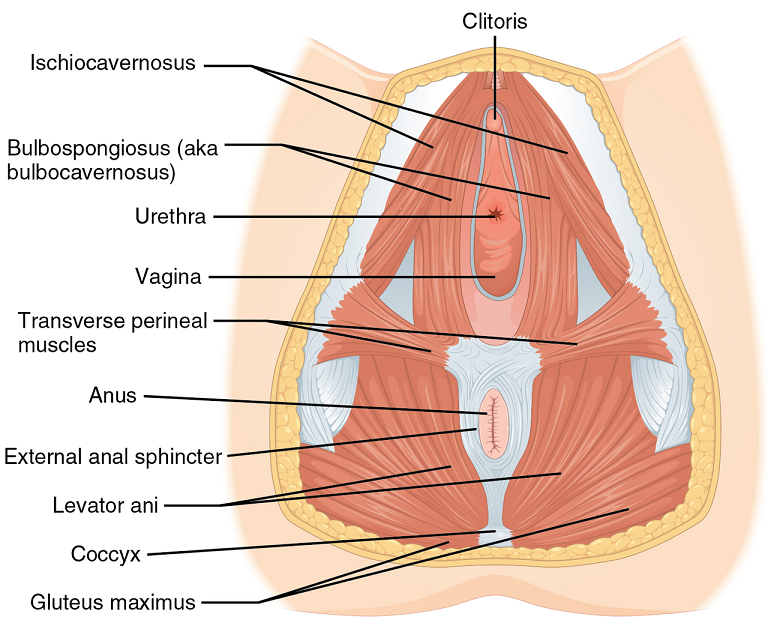

Background: The patient is a 34 y/o female who reported to the Physical Therapy clinic at 2 months postpartum from a cesarean delivery of twins. The patient was seen prior to her delivery (beginning at 24 weeks gestation) to prepare for a vaginal delivery, address chronic constipation, and to receive guidance on how to safely continue Crossfitting during pregnancy. She had been a Crossfitter (5-6 x weekly) for roughly 10 years at the time of her evaluation and was a track athlete and distance runner prior to that. Prior to pregnancy, the patient competed in local and regional Crossfit competitions in the RX division. The patient continued to Crossfit throughout her pregnancy and was able to avoid any pelvic floor dysfunction with proper modification and guidance. The patient returned for postpartum assessment at 8 weeks. At the time of the evaluation, she had begun taking short walks and performing body weight strengthening exercises. Her main concern at the time of the evaluation was a significant diastasis recti (DRA), and a self-reported decrease in core control and awareness. While the patient no longer desired to compete in local or regional competitions, she did want to continue Crossfit 5-6 x weekly and wanted to make sure she was able to safely do so with her DRA. Upon assessment, the patient’s incision was healing appropriately but did exhibit myofascial restriction that was beginning to form a slight shelf. She also had a 4-finger width separation of her linea alba, with a 2-knuckle depth at rest. Initially, the patient was unable to perform a proper transverse abdominus (TrA) contraction and was subsequently unable to create good tension across the gap. She also demonstrated compensatory recruitment of her obliques with attempts to perform a TrA contraction. The patient demonstrated mildly improved TrA recruitment in standing and following treatment, which consisted of myofascial release to her abdominal wall and incision, dry needling to her obliques, and internal trigger point release to her pfm. The pt exhibited limited pfm motor control at the time of her postpartum evaluation, and her PERF score was 2/6/5/2. The pt also exhibited myofascial restriction of her thoracolumbar fascia, proximal adductors, and B glutes. The pt continued to be seen for roughly 1 year following the delivery of her twins. In that time a variety of treatment strategies and techniques were used.

Methods: The methods used to treat this patient included education on proper pressure management strategies (including modification to breathing strategies during exercise), exercise scaling and modification, internal trigger point release to the pfm, followed by neuromuscular re-education once the normal resting tone of the pfm had returned, myofascial release to her abdominal wall and cesarean scar, dry needling, and education on a home exercise program (HEP). The pressure management strategies provided to the patient focused primarily on the various breathing patterns she could utilize to prevent breath holding, improve pelvic floor contraction, and reduce intra-abdominal pressure. The use of the Valsalva was not re-introduced until the patient had normal pfm motor control, exhibited proper tension across her DRA with no evidence of doming or conning, and only in limited circumstances (primarily when the weight was over 80% of her max for that movement). Pelvic floor motor control was assessed via internal palpation, in standing, and with a load (ie back squat and deadlift). Activity modification included modification of the speed of various movements, the load (weight) of various movements, the velocity of various movements (barbell cycling versus slow reps and strict gymnastics versus kipping), and the volume of various movements (number of repetitions or rounds/time of time of a metcon). If the patient’s tissues still could not handle the load with the above modifications, the movement was changed altogether (i.e. mountain climbers versus toe to bar). Measures used to indicate tissue tolerance to the load included: abdominal doming or coning, urinary incontinence, pelvic pain or heaviness, pulling or pain along her incision, and low back pain. If the patient experienced any of these symptoms, the movement was modified until she was able to complete the movement without symptoms. Additionally, the patient received internal trigger point release to the pfm, dry needling to the abdominal wall, glutes, proximal adductors, and lumbar paraspinals, myofascial release to the same muscle groups, neuromuscular re-education, and kinesiotaping to the abdominal wall.

Results: At the time of her discharge, the patient was able to fully return to all desired Crossfit activity. This process took roughly 1 year and required a gradual loading of her tissues through activity modification, to allow them to properly manage the load placed on them. For her, gymnastics movements on the rig took the longest to return to. She did not fully return to these movements (pull-ups, toes to bar, chest to bar pull-ups, and muscle-ups) until roughly 8-9 months postpartum. At the time of her discharge, she was able to create good tension across the gap and had improved her DRA to only less than 1 finger width separation and less than 1 knuckle of depth at rest. When performing a TrA contraction, there was no depth or width of separation. The pt also had an improved PERF score of 5/10+/10/8. The pt exhibited normal pfm motor control and excellent pressure management at the time of discharge.

Conclusion: While there is not a large amount of research available on the effects of high intensity athletics on the function of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall, we are beginning to see an increase in research on new, and more functional approaches to evaluating and treating Diastasis recti (DRA). There has also been a recent increase in research looking at the effects of various breathing techniques during exercise (including the Valsalva) and how it affects both the mother and the baby. Consistent review of the most current research, a thorough understanding of the mother’s anatomy and how it changes during pregnancy and postpartum, as well as each patient’s unique history and goals is necessary for clinicians to provide the highest quality of care for each patient. This is how we can move away from blanketed natal and postnatal exercise recommendations, and develop patient centered, sport-specific treatment plans that will allow each patient safely and effectively participate in high intensity athletics.

Pregnancy & Postpartum Considerations For High Intensity Athletics

Price: $225.00 Experience Level: Beginner Contact Hours: 8.25 hours

Course Dates: May 21, September 10, and November 19

Description: This one-day remote course is designed to educate practitioners on the unique considerations of pregnant and postpartum athletes engaging in high intensity interval training (HIIT). In this cours participants will review the current literature, discuss the unique needs of pregnant and postpartum high intensity athletes, and learn how to most effectively treat these patients as practitioners. The main focus of this course will be to learn how exercising throughout pregnancy, or returning to exercise postpartum may look different for a high intensity athlete versus a non HIIT athlete.

Participants will discuss how anatomical and hormonal changes will affect training for the pregnant and postpartum athlete, and review various modifications for this population. We will also discuss how various stresses placed on the body during these activities may affect pelvic floor muscle function, and review various pressure management strategies that can be utilized during high intensity interval training. The lab will be broken up into pregnancy considerations and postpartum considerations. During the pregnancy lab, we will review specific exercise modifications for pregnancy, utilization of breathwork to properly support the pelvic floor during pregnancy, and review how to assess for and tape for diastasis recti. In the postpartum lab we will review how to determine proper activity modification based on ability to manage pressure, review specific activity modifications and breathwork, review accessory work for return to activity, and discuss how to assess pelvic organ prolapse in standing.

Childbirth fear is associated with lower labor pain tolerance and worse postpartum adjustment.1,2 In addition, psychological distress during pregnancy is associated with adverse consequences in offspring, including detrimental birth outcomes, long-term defects in cognitive development, behavioral problems during childhood and high levels of stress-related hormones.3 These negative consequences of fear and stress during pregnancy have inspired both interest and research into the role of mindfulness training during pregnancy to reduce fear and stress and improve outcomes.

In a randomized controlled trial, first-time mothers in the late 3rd trimester of pregnancy were randomized to attend either a 2.5-day mindfulness-based childbirth preparation course offered as a weekend workshop or a standard childbirth preparation course with no mind-body focus.4 Participants completed self-report assessments pre-intervention, post-intervention, and post-birth, and medical record data were collected. Compared to standard childbirth education, those in the mindfulness-based workshop showed greater childbirth self-efficacy and mindful body awareness, reduced pain catastrophizing and lower post-course depression symptoms that were maintained through postpartum follow-up. Participants in the mindfulness workshop also demonstrated a trend toward a lower rate of opioid analgesia use in labor.

In a qualitative study, researchers conducted in-depth interviews at four to six months postpartum with ten mothers at increased risk of perinatal stress, anxiety and depression and six fathers who had participated in a Mindfulness Based Childbirth and Parenting Program (MBCP).5 The MBCP program integrates mindfulness training into childbirth education. Participants meet for eight 2 hour and 15 minute weekly sessions and a reunion after babies are born. Specific mindfulness practices introduced include body scan, mindful movement, sitting meditation and walking meditation. Also, methods to integrate mindfulness into pain management, parenting and activities of daily living are introduced. Participants are asked to practice at home for 30 min per day in between sessions supported by audio guided instructions and informative texts.

Participants in the MBCP Program described gaining new skills for coping with stress, anxiety and pain, as well as developing insight and self-compassion and improving communication. Participants attributed these improvements to an increased ability to focus and gain a wider perspective as well as adopt attitudes of curiosity, non-judging and acceptance. In addition, they described mindfulness training to be helpful for coping with childbirth and parenting, including breastfeeding troubles, sleep deprivation and stressful moments with the baby.

These findings demonstrate potential therapeutic outcomes of integrating mindfulness training into childbirth preparation. Although this is a young field and more research is warranted, there is substantial research demonstrating mindfulness training improves stress management, pain management and decreases physiological markers of stress in a wide range of patient populations.6, 7 While the interventions in the above two studies introduce mindfulness in a group format, I have also found that patients can greatly benefit from being taught mindful principles and practices in one-on-one treatment sessions.

Carolyn will share her over-30 years of training and experience teaching mindfulness to patients both individually and in group settings in her course, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, coming up on October 26 and 27 in Houston, TX. Participants will return to the clinic with skills to not only help patients, but to also help themselves be less stressed, more mindful providers!

1. Alehagen S, Wijma K, Wijma B. Fear during labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(4): 315–320.

2. Laursen M, Johansen C, Hedegaard M. Fear of childbirth and risk for birth complications in nulliparous women in the Danish national birth cohort. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009:116(10): 1350–1355.

3. Isgut M, Smith AK, Reimann. The impact of psychological distress during pregnancy on the developing fetus: Biological mechanisms and potential benefits of mindfulness interventions. J Perinat Med. 2017 Dec 20;45(9):999-1011.

4. Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Chao MT. The benefits of preparing for childbirth with mindfulness training: a randomized controlled trial with an active comparison. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017. May 12;17(1):140.

5. Lonnberg G, Nissen E, Niemi M. What is learned from Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting Education? – Participants’ experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018; 18: 466.

6. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):199-213.

7. Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Jenkins ZM, Ski CF. Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:156-78.

Everyday we as pelvic rehab providers get to help patients achieve their goals by meeting them where they are and guiding them along.

A couple of months ago I had a new patient come in to see me who was seven months status post c-section delivery of her first child. She was referred to physical therapy because she could not tolerate anything touching her lower abdomen and she was also unsure of how to start exercising again including returning to her yoga practice. I remember reading her referral and thinking that this should be a simple evaluation and treatment session. What actually happened was a little different.

Her delivery hadn’t gone the way she planned, and she was not comfortable discussing it at our first session. This patient had not looked at or touched her c-section incision besides drying it off after her shower for the seven months since delivery. Her physician had made a referral to PT and to a counselor within three months of delivery to help support the patients’ recovery. The patient had not followed through with the PT referral until she had significant encouragement from her counselor and physician.

Initially the patient declined any observation or palpation of her abdomen so at our first session we focused on thoracic range of motion, general posture, and encouraged her to start touching her abdomen through her clothes, even if avoiding direct touch to the incisional region. The patient was agreeable with this starting point. At the second session the patient was willing to have me look at her abdomen and touch the abdomen but she declined direct palpation of the scar region. With simple observation I could see a scar that was closed and healing but also that was pulled inferior towards her pubic bone. She was not comfortable laying flat on the treatment table and had to be supported in a semi-recline throughout the session. She also described buzzing symptoms at the scar region when she reached her arms overhead.

We started some gentle desensitization techniques as would be used with a person that had Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) after an injury. I focused those treatments to the abdominal region but avoided the scar region. We focused her home program on breathing into her abdomen allowing some stretch and expansion of the abdominal region. Her home program also included laying flat for five minutes per day. I asked her to notice any general tension throughout her body during the day and attempt to change it and release it if able.

By the fourth session we where able to begin direct palpation and manual therapy techniques to the c-section scar and the whole abdominal region. The patient was apprehensive but agreed to proceeding with utilizing techniques as described by Wasserman et al2018 including superficial skin rolling, direct scar mobilization and general petrissage/effleurage of the abdomen and lumbothoracic region.

Over the next five sessions the patient was able to start wearing undergarments and pants that touched her lower abdomen. She was able to perform her own self massage to the region and began an exercise program including prone press ups, progressive generalized trunk strengthening, and return to her prior-to-pregnancy yoga practice.

Drawing on the techniques we learn from multiple sources, applying them to the lumbopelvic region, and helping our patients wherever the client is in their journey to wellness, is what inspires me to keep learning.

Techniques like this are taught in my 2-day Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist course. I specifically wrote this course so that pelvic rehab therapists that are looking for more techniques and/or more confidence in their palpation skills would have a weekend to hone those skills. We spend time learning anatomy, learning palpation skills, manual techniques, problem solving home programs and discussing cases. Check out Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist - Raleigh, NC - June 22-23, 2019 for more information and I hope to see you there.

Wasserman, J. B., Abraham, K., Massery, M., Chu, J., Farrow, A., & Marcoux, B. C. (2018). Soft Tissue Mobilization Techniques Are Effective in Treating Chronic Pain Following Cesarean Section: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 42(3), 111-119.

Perineal massage involves pelvic floor muscle stretching by application of an external pressure to muscle and connective tissue in the perineal region. It is performed 4 to 6 weeks before childbirth to help the soft tissue in that region to withstand stretching during labor. This helps to prevent perineum during birth by decreasing the need for an episiotomy or an instrument-assisted delivery. Lengthening of skeletal muscles is known to modify the viscoelastic properties of the muscle-tendon unit, which decreases the tension peak of the musculature and therefore, chances of injury.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Instrument-assisted stretching is performed with the help of an inflatable silicon balloon that can be pumped to gradually stretch the vagina and perineum. However, the evidence to support its benefit is lacking. In fact, there is some concern that pelvic floor muscle stretching may cause a decrease in muscle strength. Some have argued that such exercise neither improve or worsen pelvic function (Labrecque M, et al., Medi-dan, et al.). While a meta-analysis by Aquino, et al. concluded that perineal massage during labor significantly lowered risk of severe perineal trauma, such as third and fourth degree lacerations (Aquino, et al.).

A recent major study done by deFreitas, et al., perineal massage and instrument-assisted stretching were found to improve perineal muscle extensibility when performed in multiple sessions on primiparous women beginning at 34th week of gestation, which is very helpful in preventing child trauma in labor; however, there was no increase in muscle strength.

The technique of performing the manual perineal massage (as exemplified in the aforementioned study) may involve two sessions per week for a month by an OBGYN-focused physiotherapist. The patients are rested in dorsal decubitus position with the inferior limbs semi-flexed and the lower limbs and feet supported on the examination table. Coconut oil can be used for the perineal massage - which starts off with circular movements in the external area of the vulva, around the vagina and in the central tendon of the perineum, followed by the index and middle fingers inserted approximately 4 cm in the vaginal introitus for an internal massage of the lateral walls of the vagina ending toward the anus, repeated four times on each side, with the whole process lasting approximately 10 minutes.

Instrument-assisted procedure may include inserting the instrument (Epi-No) covered with a condom and lubricated with a water-based gel, inflated at the vaginal introitus so that 2 cm of the balloon is visible, making sure the patient can tolerate the stretching, and are advised to keep the pelvic floor relaxed as the instrument is slowly expelled during expiration. Physiotherapist supervision is necessary in order to maintain the correct positioning of the balloon as it lengthens the muscles. He/she will also ensure proper expulsion of the equipment during expiration.

Overall, perineal massage techniques (with or without instrumentation) are beneficial in terms of preventing trauma during labor. There are many studies that support the efficacy of these techniques in doing so (Leon-Larios, et al.). But it is also important to appreciate the limitations and use it judiciously.

Randomized trial of perineal massage during pregnancy: perineal symptoms three months after delivery. Labrecque M, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000.

Perineal massage during pregnancy: a prospective controlled trial. Mei-dan E, et al. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008.

Perineal massage during labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aquino CI, et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018.

Effects of perineal preparation techniques on tissue extensibility and muscle strength: a pilot study. de Freitas SS, et al. Int Urogynecol J. 2018.

Influence of a pelvic floor training programme to prevent perineal trauma: A quasi-randomised controlled trial. Leon-Larios F, et al. Midwifery. 2017.

Kelly Feddema, PT, PRPC returns in a guest post on Pregnancy Associated Ligamentous Laxity. Kelly practices pelvic floor physical therapy in the Mayo Clinic Health System in Mankato, MN, and she became a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner in February of 2014. See her post on diastasis recti abdominis on the pelvic rehab report, and learn more about evaluating and treating pregnant patients by attending Care of the Pregnant Patient!

Pregnancy associated ligamentous laxity is something that we, as therapists, are fairly well aware of and see the ramifications of quite often in the clinic. We know the female body is changing to allow the mother to prepare for the growth and birth of the tiny (or sometimes not so tiny) human she is carrying. We also know that the body continues to evolve after the birth to eventually return to a post-partum state of hormonal balance. Do we think much about what this ligamentous laxity can mean during the actual delivery? Does laxity predispose women to other obstetric injury?

Pregnancy associated ligamentous laxity is something that we, as therapists, are fairly well aware of and see the ramifications of quite often in the clinic. We know the female body is changing to allow the mother to prepare for the growth and birth of the tiny (or sometimes not so tiny) human she is carrying. We also know that the body continues to evolve after the birth to eventually return to a post-partum state of hormonal balance. Do we think much about what this ligamentous laxity can mean during the actual delivery? Does laxity predispose women to other obstetric injury?

A recent study in the International Urogynecology Journal assessed ligamentous laxity from the 36th week of pregnancy to the onset of labor by measuring the passive extension of the non-dominant index finger with a torque applied to the second metacarpal phalangeal joint. They collected the occurrence and classification of perineal tears in 272 out of 300 women who ended up with vaginal deliveries and looked for a predictive level of second metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) laxity for obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI). They concluded that the increased ligamentous laxity did seem associated with OASI occurrence which was opposite of their initial idea that more lax ligaments would be at less of a risk of OASI.

In another study from the same journal published in 2017, researchers studied if levator hiatus distension was associated with peripheral ligamentous laxity during pregnancy. This was a small study but they concluded that levator hiatus distension and ligamentous laxity were significantly associated during pregnancy. They did admit the relationship was weak and results would have to be confirmed with a larger study and more specific study methods. However, the likelihood of major levator trauma more than triples during the reproductive years from under 15% at age 20 to over 50% at age 40(University of Sydney) so it seems that these issues warrant continued study with the continued trend toward delayed child bearing in Western cultures.

Gachon, B., Desgranges, M., Fradet, L. et al. Int Urogynecol J (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3598-2

Gachon, B., Fritel, X., Fradet, L. et al. Int Urogynecol J (2017) 28: 1223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3252-9

University of Sydney. "Levator Trauma" sydney.edu.au. Accessed 25 April 2018.

Today's guest post comes to us from Kelly Feddema, PT, PRPC. Kelly practices pelvic floor physical therapy in the Mayo Clinic Health System in Mankato, MN, and she became a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner in February of 2014. To learn more about diastasis recti abdominis, consider attending Care of the Postpartum Patient!

It can be a struggle to treat patients with diastasis recti if they don't seek treatment early after giving birth. Many therapists may often find themselves thinking “if I only could have started them sooner.” Why does this condition often get missed at postpartum examinations? I personally deal with symptoms from an undiagnosed diastasis, and I'm a therapist! I didn’t really pay attention to it until I started down the road of becoming a pelvic floor therapist.

Diastasis recti can be a difficult diagnosis to treat, as the patient may come to us when they are already one year postpartum, and not everyone agrees on the what are the best treatments. To crunch or not crunch? To use a brace or not to brace? It would be great if we had a similar healthcare system to France, where the norm is to have 10-20 postpartum rehabilitation visits with women after child birth. While therapy is available in the United States, women must ask for it.

Diastasis recti can be a difficult diagnosis to treat, as the patient may come to us when they are already one year postpartum, and not everyone agrees on the what are the best treatments. To crunch or not crunch? To use a brace or not to brace? It would be great if we had a similar healthcare system to France, where the norm is to have 10-20 postpartum rehabilitation visits with women after child birth. While therapy is available in the United States, women must ask for it.

There are many programs out there from the more well-known Tupler Technique and Mutu programs to others that come up when searching for exercise ideas. The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) has a basic program to work on isolating the transverse abdominis (TrA) muscle and then progressing movements in the legs while keeping the TrA activated.

Some research by Paul Hodges and Diane Lee from 2016 in the Journal of Orthopedic Sports Physical Therapy indicates that narrowing the inter-rectus distance with a TrA contraction might improve force transfer between the sides of the abdominals and in turn, improve abdominal mechanics.

Another study in Physiotherapy from December of 2014 by AG Pascoal, et.al. utilized ultrasound to determine the effect of isometric contraction of the abdominal muscles on inter-rectus distance in postpartum women. They found that the while the inter-rectus distance in postpartum women was understandably higher than controls, it significantly lowered during an isometric contraction of the abdominal muscles.

One year later, a study in the same journal by MF Sancho, et.al. had similar findings when studying women who had a vaginal delivery and women who had Cesarean deliveries. They found that abdominal crunch exercises were successful in reducing inter-rectus distance, but drawing-in exercises were not.

As with a lot of research, the findings lead to more questions and ideas to explore. I think it is safe to say that starting safe re-education of the muscles as early as possible is going to provide women the most benefit in reducing diastasis recti, and that will help to prevent further issues in the abdominal and pelvic region.

As practitioners, we understand the value of a yoga practice for multiple systems. Yoga improves cardiovascular function, pulmonary function, improves flexibility, builds strength, improves balance, and cultivates resiliency. Prenatal yoga is deemed safe and widely practiced. Beyond not laying prone after the first trimester, what are modifications for practicing yoga while pregnant? Is there any evidence to demonstrate if specific yoga postures are safe from both the maternal and fetal perspective?

Polis et al set out to determine the safety of specific yoga postures using vital signs, pulse oximetry, tacometry, and fetal heart rate monitoring. The patients were diverse in age, race, BMI, gestational age, parity, and yoga experience. Exclusionary criteria included preeclampsia, placenta previa, bleeding in the 2nd or 3rd trimester, gestational diabetes, BMI greater than 35 and other medical conditions that presented contraindications.

Polis et al set out to determine the safety of specific yoga postures using vital signs, pulse oximetry, tacometry, and fetal heart rate monitoring. The patients were diverse in age, race, BMI, gestational age, parity, and yoga experience. Exclusionary criteria included preeclampsia, placenta previa, bleeding in the 2nd or 3rd trimester, gestational diabetes, BMI greater than 35 and other medical conditions that presented contraindications.

The maternal and fetal responses were tested in 26 yoga postures. The selected postures, much like most yoga classes, offered a variety of physical positions. The standing, seated, twists and balancing postures chosen were: Easy Pose, Seated Forward Bend, Cat Pose, Cow Pose, Mountain Pose, Warrior 1, Standing Forward Bend, Warrior 2, Chair Pose, Extended Side Angle Pose, Extended Triangle Pose, Warrior 3, Upward Salute, Tree Pose, Garland Pose, Eagle Pose, Downward Facing Dog, Child’s Pose, Half Moon Pose, Bound Angle Pose, Hero Pose, Camel Pose, Legs up the Wall Pose, Happy Baby Pose, Lord of the Fishes Pose and Corpse Pose.

Balancing postures were modified to decrease fall risk. Warrior 3, Tree Pose, Eagle Pose, and Half Moon Pose were performed at the wall or using a chair for support. The addition of a yoga block to bring the floor closer to the practitioner was used for Extended Side Angle Pose, Extended Triangle Pose, and Garland Pose.

Four poses that have previously been theorized to be contraindicated were studied in this group. These postures are Child’s Pose, Corpse Pose, Downward Facing Dog, and Happy Baby. No adverse reactions were discovered for this specific population during the intervention or in the 24 hour follow-up as reported by email.

Now that we have this data, what do we do with it?

We have the opportunity to educate our non-high-risk patients that the previously theorized contraindicated postures listed above were safe for the self-selected group in this study. Those who are in high-risk categories should understand that even though yoga is not a high impact activity, there should be clearance from the OB team to ensure expectant mothers are moving as safely as possible. With proper guidance, yoga is a safe form of exercise and stress reduction which can optimize physical and mental health during the prenatal period and prepare for birth.

Dustienne Miller is the author and instructor of Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Join her in Kansas City, MO on April 7, 2018 - April 8, 2018 to learn about treating interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, vulvar pain, coccydynia, hip pain, and pudendal neuralgia with a yoga approach.

Polis RL, Gussman D, Kuo YH. Yoga in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:1237–41

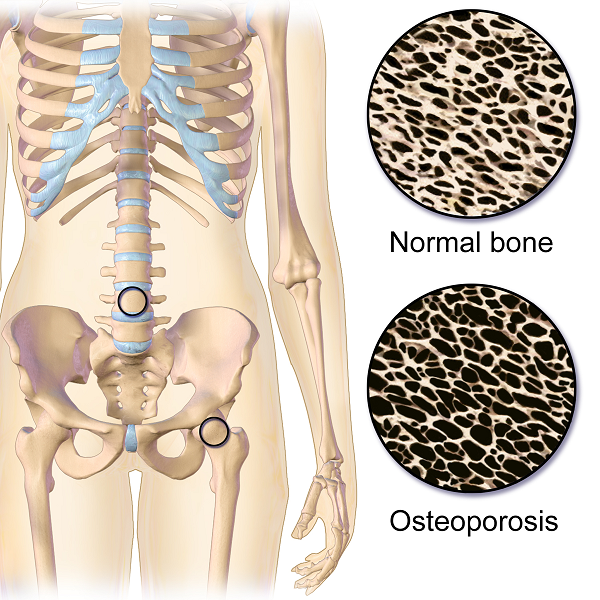

On my son’s due date, I ran 5 miles (as I often did during my pregnancy), hoping he would be a New Year’s baby. The thought of low bone density never crossed my mind, even living in Seattle where the sun only intermittently showers people with Vitamin D. However, bone mineral density changes do occur over the course of carrying a fetus through the finish line of birth. And sometimes women experience a relatively rare condition referred to as pregnancy-related osteoporosis.

Krishnakumar, Kumar, and Kuzhimattam2016 explored vertebral compression fracture due to pregnancy-related osteoporosis (PAO). The condition was first described over 60 years ago, and risk factors include low body mass index, physical inactivity, low calcium intake, family history, and poor nutrition. Of 535 osteoporotic fractures considered, 2 were secondary to PAO. A 27-year-old woman complained of back pain during her 8th month of pregnancy, and 3 months postpartum, she was found to have a T10 compression fracture. A 31-year-old with scoliosis had back pain at 1 month postpartum but did not seek treatment until 5 months after giving birth, and she had T12, L1, and L2 compression fractures. The women were treated with the following interventions: cessation of breastfeeding, oral calcium 100 mg/day, Vitamin D 800 IU/day, alendronate 70 mg/week, and thoracolumbar orthosis. Bone density improved significantly, and no new fractures developed during the 2-year follow up period.

Nakamura et al.2015 reviewed literature on pregnancy-and-lactation-associated osteoporosis, focusing on 2 studies. The authors explained symptoms of severe low back, hip, and lower extremity joint pain that occur postpartum or in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy can be secondary to this disorder, but it is often not considered immediately. A 30-year-old woman with such debilitating pain in her spine with movement 2 months postpartum had to stop breastfeeding, and 10 months later, she was found to have 12 vertebral fractures. She had low bone mineral density (BMD) in her lumbar spine, and she was given 0.5mg/day alfacalcidol (ALF), an active vitamin D3 analog, as well as Vitamin K. No more fractures developed over the next 6 years. A 37-year-old female had severe back pain 2 months postpartum, and at 7 months was found to have 8 vertebral fractures due to PAO. Her pain subsided after stopping breastfeeding, using a lumbar brace, and supplementing with 0.5mg/day ALF and Vitamin K. The authors concluded goals for treating PAO include preventing vertebral fractures and increasing BMD and overall fracture resistance with Vitamins D and K.

Other treatment approaches for similar case presentations have been published. One gave credit to denosumab injections giving pain relief and improved BMD to 2 women, ages 35 and 33, after postpartum vertebral fractures (Sanchez, Zanchetta, & Danilowicz2016). Guardio and Fiore2016 reported success using the amino-bisphosphonates, neridronate, in a 38-year-old with PAO T4 fracture.

Thankfully for these women experiencing PAO vertebral fractures, supplements boosted their BMD and prevented further fractures. However, they all had to prematurely stop breastfeeding to reduce their pain as well. This rare condition can be used as a warning for women to proactively increase their BMD. The course, Meeks Method for Osteoporosis, can help therapists implement safe, effective, and active ways to promote bone health for all - especially the pregnant population in serious need of support.

Krishnakumar, R., Kumar, A. T., & Kuzhimattam, M. J. (2016). Spinal compression fractures due to pregnancy-associated osteoporosis. Journal of Craniovertebral Junction & Spine, 7(4), 224–227. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8237.193263

Nakamura, Y., Kamimura, M., Ikegami, S., Mukaiyama, K., Komatsu, M., Uchiyama, S., & Kato, H. (2015). A case series of pregnancy- and lactation-associated osteoporosis and a review of the literature. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 11, 1361–1365. http://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S87274

Sánchez, A., Zanchetta, M. B., & Danilowicz, K. (2016). Two cases of pregnancy- and lactation- associated osteoporosis successfully treated with denosumab. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism, 13(3), 244–246. http://doi.org/10.11138/ccmbm/2016.13.3.244

Gaudio, A., & Fiore, C. E. (2016). Successful neridronate therapy in pregnancy-associated osteoporosis. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism, 13(3), 241–243. http://doi.org/10.11138/ccmbm/2016.13.3.241

So many physiological changes occur to a woman’s body during pregnancy, it is no wonder that pregnant women have back and lower extremity aches and pains. These women experience hormonal changes, weight gain, reduced abdominal strength, and their center of mass shifts anteriorly. These physiological changes result in altered spinal and pelvic alignment, and increased joint laxity. Also, many women report increases in size of their feet and a tendency to have flatter arches during and after pregnancy. Alignment changes may influence pain. Altered alignment could change the physical stresses placed upon different tissues of the body, which that specific tissue was not adapted to, therefore, causing pain or injury to that tissue.

A recent study published in 2016, in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1, investigated if there may be a relationship between anthropometric changes of the foot that occur with pregnancy, and pregnancy related musculoskeletal pain of the lower extremity. The study included 15 primigravid women and 14 weight matched controls. This study was a repeated-measurements design study, where the investigators measured foot length, foot width, arch height index, arch rigidity index (ARI), arch drop (AD), rear foot angle, and pelvic obliquity during the second and third trimesters and post-partum. The subjects were surveyed on pain in the low back, hips/buttocks, and foot/ankle.

A recent study published in 2016, in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1, investigated if there may be a relationship between anthropometric changes of the foot that occur with pregnancy, and pregnancy related musculoskeletal pain of the lower extremity. The study included 15 primigravid women and 14 weight matched controls. This study was a repeated-measurements design study, where the investigators measured foot length, foot width, arch height index, arch rigidity index (ARI), arch drop (AD), rear foot angle, and pelvic obliquity during the second and third trimesters and post-partum. The subjects were surveyed on pain in the low back, hips/buttocks, and foot/ankle.

The author’s findings were that measures of arch flexibility (ARI and AD) correlated with pain at the low back and the foot and ankle. They concluded that medial longitudinal arch flexibility may be related to pain in the low back and foot. The more flexible arches were associated with more pain in the study participants. They reported the participants in their study did not have very high pain levels in general, and recommend further studies to compare pregnant women who experience severe pain with women who do not while comparing their alignment factors. This article is a good reminder for physical therapists to consider the changes that occur to the foot including changes in arch height, arch flexibility, and foot size and how that influences the pelvis and lower extremity for prevention and treatment of musculoskeletal pain during pregnancy.

Educating our pregnant patients on shoe wear seems even more important now. Making recommendations, unique to each individual patient based on their objective data, foot type, and arch flexibility status seems like an appropriate addition to a well-rounded treatment plan. Doesn’t it seem prudent to wear shoes that provide some arch support to hopefully reduce musculoskeletal pain associated with pregnancy changes? I have observed some patients who are pregnant arrive to physical therapy wearing unsupportive flip flops and other poor shoe wear choices. I understand there are barriers for pregnant patients, I remember from when I was pregnant that reaching your feet to put shoes on can be very difficult, and sometimes your feet are swelling so it may be near impossible to physically get shoes on your feet. You might even need a new pair of shoes, as your shoes may no longer fit. However, an article such as this one, seems like something I could easily share with a patient to help persuade them of the importance of good shoe wear or at least proper arch support. Being able to discuss a recent scientific study with a patient can be powerful and motivating to a patient. Additionally, an article such as this reminds a practitioner of specific objective data to monitor such as arch height and flexibility as it changes throughout the patient’s pregnancy. How does the patient’s changing arch height and flexibility influence their specific pelvic, hip, knee, and ankle alignment? How does swelling play a part in the patients’ foot anthropometrics day to day, trimester to trimester? Ask more questions about their daily activities, are they ‘barefoot and pregnant’? Could something as simple as having them wear appropriate, arch supportive shoes while in the home reduce their lower extremity or back pain?"

Harrison, K. D., Mancinelli, C., Thomas, K., Meszaros, P., & McCrory, J. L. (2016). The Relationship Between Lower Extremity Alignment and Low Back, Hip, and Foot Pain During Pregnancy: A Longitudinal Study of Primigravid Women Versus Nulliparous Controls. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 40(3), 139-146.

Preterm birth can have deleterious health effects not only for the child, but also for the mother. A child may be born so early that various health systems are not matured, leading to susceptibility and delay in development and growth. Maternal health may also be severely impacted, with conditions such as anxiety and psychological stress. Managing the prevention of a pre-term delivery can be stressful and challenging for a pregnant woman, and authors Ha & McDonald (2016) report that this issue is not well studied. A cross-sectional survey was completed to find out not only what a woman’s preferences and concerns are, but also to find out which recommendations were likely to be followed by the patient. This is important, the authors state, because women who are actively involved in medical decisions are more likely to feel satisfied with their childbirth experience.

The survey was completed by 311 women at a median of 32 weeks gestation. Mean age was 30.9, and the majority of them identified as European/White-Caucasian. Most of them were married or in a common-law relationship and had received some level of post-secondary education. The majority of women who were told they were at increased risk of preterm labor (PTL) preferred close-monitoring rather then PTL prevention. Of interest is that the majority of women reported they would use other sources of information besides their primary provider, with the most reported source being the internet or family and friends. This point begs the question of how high is the quality level or accuracy of the available information on the internet or in the general public? Common available options for prevention included progesterone, cerclage, and pessary use. If a woman is not interested in using recommended prevention strategies, the goal of the rehabilitation clinician should be to, on a constant basis, monitor for symptoms and signs of early labor, and encourage the patient to keep any recommended provider appointments, and stay in close contact with her provider so that close-monitoring may be carried out.

An additional goal for rehabilitation is to provide the mother with strategies that may assist her in managing her anxiety, stress, movement dysfunctions, sleep, and other activities. Prior research has validated the benefits of relaxation training in pre-term labor: a cost-effective, low risk and easily implemented strategy. Training women in such a tool during pregnancy fits well into the rehab provider’s scope, and can be instructed in the clinic (or home!) for home program implementation. Larger newborns, longer gestations, and higher rates of prolonged gestations have been recorded when using relaxation training training for pre-term labor.Janke et al., 1999) Chuang et al. (2012) have documented fewer admissions to neonatal intensive care unit, decreased rates of extreme pre-term birth, and shorter stays in hospital with use of relaxation training. Meditation, mindfulness, deep breathing, visualization, and movement within recommend medical limits may all be valuable tools that make up a part of a patient’s rehabilitation experience. In an article describing how prenatal meditation influences infant behaviors, yoga, singing, and massage therapy are all cited methods for improving maternal and/or fetal health.Chan, 2014

The Herman & Wallace Institute offers a three part series on pregnancy and postpartum. Get started by attending either Care of the Pregnant Patient or Care of the Postpartum Patient. You may also be interested in any of the Mindfulness & Meditation courses, including Holistic Interventions and Meditation, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, and Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals.

Chan, K. P. (2014). Prenatal meditation influences infant behaviors. Infant Behavior and Development, 37(4), 556-561.

Chuang, L.-L., Lin, L.-C., Cheng, P.-J., Chen, C.-H., Wu, S.-C., & Chang, C.-L. (2012). The effectiveness of a relaxation training program for women with preterm labour on pregnancy outcomes: A controlled clinical trial. [Article]. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49, 257-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.007

Ha, V., & McDonald, S. D. (2017). Pregnant women’s preferences for and concerns about preterm birth prevention: a cross-sectional survey. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 17(1), 49.

Janke, J. (1999). The effect of relaxation therapy on preterm labor outcomes. Journal Of Obstetric, Gynecologic, And Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN / NAACOG, 28(3), 255-263.