Mia Fine, MS, LMFT, CST, CIIP has written and instructing her remote course, Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists, with H&W on June 5-6, 2021. Mia (they/she) is a student of Queer Theory, Intersectionality, and Social Justice, and offers holistic, anti-oppressive, and trauma-informed therapy. This is a course intended for pelvic rehab therapists who want to learn tools and strategies from a sex therapist’s toolkit who work with patients experiencing pelvic pain, pelvic floor hypertonicity, and other pelvic floor concerns.

Let’s talk terms: Dyspareunia and Vaginismus

- Vaginismus: involuntary contraction of vaginal muscles preventing insertion/penetration

- Dyspareunia: pain felt during penetration

Symptoms (not limited to): pain - painful penetration, painful orgasms, painful periods, painful pelvic exams, inability to use tampons/cups, urinary or bowel hesitancy, feeling “too tight”

Causes (not limited to): stress, relationship concerns, mood concerns (anxiety, depression), insufficient arousal/desire/interest, trauma, side effects of meds, negative attitudes towards sex, and other pelvic pain concerns such as a tilted uterus.

The deal is, when it comes to dyspareunia and vaginismus there’s a cycle that can be difficult to break. The cycle is: you feel pain, then you feel broken (shame about feeling pain), then anxiety that pain will happen again, then you tighten your pelvic floor, and the cycle repeats. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Often unwanted sexual pain goes unaddressed. Why? Because we are not taught about the interactions between feelings, relationships, and our body. We are not taught that sex should not be painful; that pain is (likely) our body giving us information that something is going on (Hello crappy sex education and the stigma of sexual health and body awareness!). It’s not uncommon that most people who experience sexual pain often feel they are broken.

You are not broken

How to heal from unwanted sexual pain? There’s a trifecta! Effective healing comes from working with a sex-positive medical provider, sex therapist, and pelvic floor PT. We will all collaborate!

Sex is not supposed to be painful. You are not broken.

Mia ️

#therapy #sextherapy #wellness #health #awareness #mentalhealth #bodyawareness

Steve Dischiavi holds credentials as a licensed physical therapist and a certified athletic trainer. He also has a manual therapy certification from the Ola Grimsby Institute and is board certified by the American Physical Therapy Association as a Sports Clinical Specialist (SCS).

The blog you’re about to read is targeted at clinicians just like myself. I was taught in PT school to evaluate the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) via a movement-based analysis. I even went on for a certification in manual therapy nearly 2 decades ago, and again was taught the movement-based approach. Well, as the song goes… “times they are a changin”….

So… if you’re a clinician who will diagnosis the SIJ as being “unstable” from movement-based testing, using tests that evaluate the positional movement of the PSIS… then you need to begin to question the approach you’re taking.

There is a contemporary conversation taking place within the field of physical therapy. If you’re like me and learned to evaluate the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) through movement-based testing, you need to be involved in this evolving conversation.

A great place to start is with a “Perspective” article published in Physical Therapy in 2019. It is titled “Changing the Narrative in Diagnosis and Management of Pain in the Sacroiliac Joint Area” written by Thorvaldur Palsson, et.al.1

The narrative dives into several areas pertaining to the treatment of this mysterious region of the body. It gives the reader a thoughtful and contemplative view of the contemporary conversation surrounding the evaluation and treatment of the SIJ.

The target audience should be the clinicians who continue to evaluate the SIJ solely on movement based analysis, attempting to diagnosis the SIJ with terms related to movement dysfunction. We have all heard terms like “upslip, downslip, or sacral torsions”. The narrative addresses why this is not the best approach to diagnosing the SIJ.

The article also touches on the concepts of “pain science” and how assessing how the SIJ “moves” tells the clinician very little about why the tissues about the SIJ might be sensitized. The article scratches the surface about the patient’s pain experience and how harmful terms such as “instability” and how the SIJ “goes out” are ways that can perpetuate and even heighten the pain experience for your patients.

The Perspective article gives the reader a great introduction as to why you might consider altering your approach to the SIJ. I’ll leave you with a quote directly from the article:

“If clinical decisions are based on a construct that lacks plausibility and clinical tests lacking in validity and reliability, the entire management paradigm must be questioned.”

The next question you might be asking yourself… ok, how do I learn a new management paradigm? A great start would be to take the 4-hour introductory webinar, Sacroiliac Joint Current Concepts - Remote Course - June 26, 2021, offered by Herman and Wallace… learn the evidence-based approach to the SIJ with Steve Dischiavi, PT, DPT, MPT, SCS, ATC, COMT who has been working closely on the hip and pelvis for over 20 years!

I hope to see you at the webinar!

1. Palsson TS, Gibson W, Darlow B, et al. Changing the Narrative in Diagnosis and Management of Pain in the Sacroiliac Joint Area. Phys Ther. 2019;99(11):1511-1519.

Dustienne Miller is the creator of the two-day course Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Dustienne passionately believes in the integration of physical therapy and yoga in a holistic model of care, helping individuals navigate through pelvic pain and incontinence to live a healthy and pain-free life.

I’m one of the small business owners who has survived this difficult time. Day after day I would mask up, put on the filtration systems, and be filled with gratitude that I could still safely do my work in the world. Despite being vigilant on sleep, eating lots of veggies from the local farm, exercising, and staying well hydrated I still carry a deep covering of stress and tension.

We have been holding our breath literally and figuratively with collective humanity for the past year. I realized when I had an acute flare of lumbopelvic pain that I had to melt away layer by layer of holding tension in both my back and ribs and go deeper into my breathwork and meditation practice.

I share this to acknowledge that as health care providers we are caring for more than just the physical concerns of our patients. We are honored to witness their grief, which could be from any type of trauma (physical, medical, etc). We are chosen to be their trusted source of advice which often goes beyond the rehab lens. We also need to notice when we as clinicians (and humans experiencing a global pandemic) experience burnout.

We teach our patients how breathing patterns inform our digestion, our spine, our emotional state, our pelvic floor, etc. It’s one of the most powerful tools we have to inform our system that we are safe. Despite this knowledge, we will often find ourselves holding our breath or breathing in non-optimal ways without even realizing it. When we don’t want to feel something we don’t breathe. When we are afraid we hold our breath. We might even find our ribs stay tight even when we feel relaxed.

Let’s pause to notice and soften.

Notice your body without “fixing” your posture. Where is your ribcage in relationship to your pelvic floor? What does it feel like when you breathe in? What does it feel like when you breathe out?

If you are sitting, slouch down. How does breathing feel in this position? Now imagine your head is getting magnetically pulled up towards the ceiling and sit in a more lengthened position. Take a breath with a taller spine. Does it feel different?

Now try this with your eyes closed: imagine the intercostal space widens with each inhale - then softens during each exhale. Do you have a habit of holding your ribs open with tension? Picture your shoulders softening, as if the tension from the upper traps was melting away. The jaw softens, the tongue softens, the center of the forehead softens.

Now take another long, conscious breath. What do you notice?

As practitioners, we give so much to our patients. It serves us to stay grounded in our bodies and as relaxed as we can be while we work. It’s a tall order and hard to remember but it might help decrease fatigue, exhaustion, physical pain, and burnout. Let’s all try and keep our breaths long, jaws soft, and pelvic floors pliable. I hope this pause was useful for you!

Dustienne Miller can be found teaching her course Yoga for Pelvic Pain online for 2021 on the following dates:

May 15-16, July 31-Aug 1, and Sept 25-26

;Aparna Rajagopal, PT, MHS is the lead therapist at Henry Ford Macomb Hospital's pelvic dysfunction program, where she treats pelvic rehab patients and consults with the sports therapy team. Her interests in treating peripartum patients and athletes allowed her to recognize the role that breathing plays in pelvic dysfunction. She has co-authored the course, "Breathing and the Diaphragm: Pelvic and Orthopedic Therapists", which helps clinicians understand breathing mechanics and their relationship to the pelvic floor.

A few months ago a young woman with a diagnosis of dyspareunia was referred to me. She had been a gymnast through her teens and now worked out regularly. She reported being unable to use tampons throughout her life, experiencing difficulty with undergoing pelvic examinations, and inability to have intercourse with her partner all through her married years. She also had a history of long-standing constipation and urinary symptoms including increased voiding frequency and the feeling of incomplete emptying.

Her examination included significant overactivity of her abdominals. A very chest dominant pattern of breathing with very limited lower lateral costal expansion, limitations in thoracic mobility, a fairly rigid rib cage with a very narrow infra sternal angle, connective tissue restrictions of the abdominal, pelvic areas, decreased flexibility of her hamstrings, and weakness of her Glut Max muscles. There was significant guarding and an internal assessment of pelvic floor muscles was not performed initially due to associated discomfort.

Throughout the first few sessions, we worked on releasing her first rib, the scalenes, latissimus dorsi, and quadratus lumborum muscles, and worked on reducing the connective tissue restrictions in the abdominal and pelvic regions. We also spent time improving rib cage and thoracic spine mobility and reducing the chest dominant pattern of breathing; while trying to establish improved abdominal compliance and lateral costal expansion with inhalation. All this, along with techniques aimed at improving neuromuscular control of her Gluteus Maximus without excess compensatory pelvic floor muscular assistance led to enough improvement in a few sessions to allow for an internal pelvic floor muscle assessment to be performed.

The patient's job activities required constant vocalization and I found that she contracted her neck, her abdominal, and pelvic floor muscles very strongly with any vocalization and did not relax the muscles after she finished vocalization. The patient was educated on softening her vocalization, and on a more controlled release of air through the glottis with more gradual abdominal and pelvic floor contractions while performing glottal/vocalization exercises. The patient was very keen on continuing her fitness-related activities through all of her therapy. Manual internal pelvic floor muscle assessment performed with standing activities revealed that although she did not particularly find her workout routine very taxing she tended to exhale extremely forcefully with each repetition of the exercise. This forceful exhale was naturally accompanied by very strong recruitment of her abdominals and her pelvic floor muscles, and once again there was decreased relaxation after cessation of her exercises. The treatment process involved making the patient aware of breath patterns and her gripping, nonrelaxing quality of the contractions of the pelvic floor and the abdomen and how she could gain some relaxation by utilizing her breath.

In addition to continuing to receive pelvic therapy from me, the patient consulted with Leeann, a sports-trained therapist, for 2 sessions to set up a fitness program. Leeann set up a program for the patient to strengthen her core and gluteal muscles while monitoring the pelvic floor externally. The fitness program progressed with challenging exercises in non-weight bearing and quadruped positions which were then progressed to kneeling and then standing. An important focus during the development of this program was on monitoring the patient's strength of exhaling and ensuring pelvic floor relaxation with breathwork between repetitions ensuring that there was no reverting to the old habit of gripping.

The patient's complaints for which she initially sought pelvic therapy were completely resolved. The patient's pelvic pain symptoms were resolved with treatment directed at the thorax, the breath, vocalization and the glottis, and lower extremity muscle strength. Very little time was spent on conventional manual techniques applied directly to the pelvic floor musculature.

In the Herman and Wallace course, you will learn skills to effectively assess the thorax, the diaphragm, breathing patterns, thoracic mobility inclusive of joint mobility, and myofascial connections. Come and learn how postural changes can affect the biomechanics of how the body performs and in turn affect intra-abdominal pressure. Learn easy effective strategies that will help you in your care of patients with low back pain and pelvic floor dysfunction the very next day. Hope to see you in class!

;Aparna Rajagopal will be co-teaching Breathing and the Diaphragm: Pelvic and Orthopedic Therapists on May 15-16, 20201 with her colleague Leeann Taptich. This course instructs practitioners on breathing mechanics and their relationship to the pelvic floor.

This is Part 2 of Tuesday's, April 27, 2021, blog Misbehaving Bladders and Cluster Drinking - A Novel Approach, Part 1.

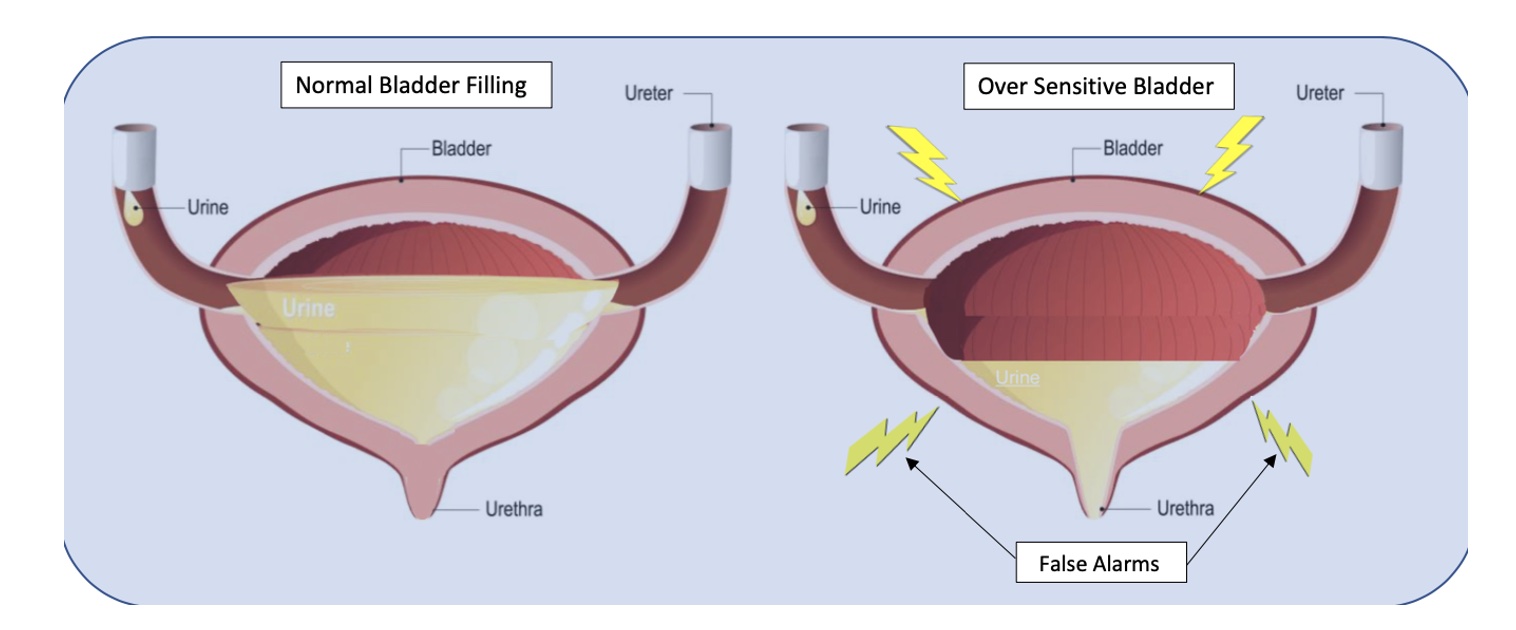

Bladder capacity ranges from around 400-500ml (13-16 oz). The use of a measuring cup or water bottle can be very helpful to teach this concept. We certainly don’t have to strive for a full bladder volume, but it is important to illustrate that 2-3 ounces are in fact “just in case” voids. I explain to patients that in situations of overactive or irritated bladders, the receptors in their bladder walls are hypersensitive and sending “false alarm” messages when only a small amount of urine is present. The kidneys are always active and refilling the bladder, so it will never be totally empty per se, therefore it must be desensitized and retrained to be a viable, reliable, and reasonably comfortable storage vessel.

With the Cluster Drinking Approach, it is important to try and drink the fluid in a short enough period of time to ensure an increased rate of bladder filling for this to be effective, but you must be careful to monitor the bladder irritability with the training. A fuller bladder will experience more pressure, but this also helps with urine flow during voids. We then embark on this process of retraining and using their bladder diaries to help us with detective work to determine optimal amounts of fluid intake in each cluster and the optimal timing of fluid intake, number of clusters, etc. for their daily schedules. It may take some time to get used to the new habits. It can be hard for some patients who are used to sipping on their water bottle all day long, and they can feel dehydrated. This is a habit and learned response and can be retrained with some gradual investment in the process. Once patients experience the rewarding outcomes, they are usually willing to make the changes.

Based on diary findings, we modify types of fluids as necessary, my motto being: minimal disruption to achieve desired results. Why give up coffee and all favorite beverages if not necessary? Sometimes making modifications on timing and amount of intake works just fine, other times we tweak the beverage types. I also teach and integrate urge suppression strategies (USS) as well, to help with the process of retraining; and of course, address breathing, pelvic floor dysfunctions, connective tissue restrictions, and chronic constipation, but the variable which sets this approach apart is the cluster drinking.

According to Washington state urogynecologist Elizabeth A. Miller, MD FPMRS, a practitioner at Overlake and Swedish Medical Centers, the Cluster Drinking Approach works similarly to some OAB medications in training your bladder to hold more urine. She endorses the Cluster Drinking Approach as a viable first-line treatment option since it works naturally without harmful side effects. Results are often profound and rapid even for folks who have been struggling with these bladder issues for years. Likewise, leaking issues tend to diminish as the bladder training is mastered. Patients can structure riskier activities around this cluster program, i.e. plan their Zumba after cluster intake and output. The same goes for major outings where one will not be near a bathroom. Even my constipation patients have benefitted due to a more reliable intake of adequate fluid.

Nocturia is a bit of a different situation because of the role of kidney hormones, but I have found this approach to be quite effective for many patients whose lives and sleep are impacted by this problem. The Cluster Drinking Approach helps these patients to structure their fluid intake during daytime hours, and I teach them to heed the 1st overnight urge if it is within 2-3 hours after going to sleep. Then if they awaken again, I coach them to use the mantra “the bladder is a storage vessel”, analyze their last intake and output, and permit themselves to use the Urge Suppression Strategies, and go back to sleep without worrying that their bladder will explode. The other good news is after their bladders (and brains) are “retrained”, and you have done your PT magic, they can often return to more natural drinking patterns without negative consequences.

Fun Fact: Even Did you know that under anesthesia the amazing expandable bladder can hold over 1 liter?!

Kathy E. Golic, PT is a physical therapist at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Washington.

There have been many constructive blogs about managing symptoms of overactive and misbehaving bladders, but I want to share an approach I have been using successfully for many years. Not only does this approach work for the majority of my patients in terms of addressing urgency, frequency, and urine leakage, but results are often quite rapid. After treating patients with modest success for many years with the traditional treatment approaches and noting that too often patients would plateau or results were just not effective or fast enough, I created my own approach to help these patients. I call it Cluster Drinking Approach and explain to my patients that cluster drinking begets cluster voiding.

When folks sip fluid, even water, all day long, it is hard for them to know when their bladder is full enough to warrant a trip to the bathroom. In patients with oversensitive or irritated bladders, the sensory receptors in the bladder wall are agitated and so often send false, unreliable signals,

when there is not much urine present. So they continue to struggle with urges and frequency and sometimes urine leakage. However, when they divide their fluid intake into 3-4, or sometimes even 5 or more, “clusters” then their bladders fill more predictably. They can sense it, and based on timing and amount of intake, they can reliably determine when the urges are accurate.

This requires a mindful and analytical approach to help retrain their bladders. The amount of intake and number of clusters are selected based on the level of bladder irritability, the patient’s schedule, as well as their weight, age, and level of anxiety. The variables can be modified according to their daily schedules, and their progress. Coupled with my mantra, “The bladder is a storage vessel, it is meant to hold urine!” this approach has been life-changing for many patients, and often in just a few visits!

Here is an example to illustrate what this might look like based on 60 fluid oz of daily intake. And important to share this pearl...In case you did not know...the adage of 8 glasses of 8 ounces of water was not based on research. So this will be quite individualized.

INTAKE

Cluster 1: 7:00 am-7:30am Consume 20 oz of fluid

Cluster 2: 11:30-12:00 Consume next 15 oz

Cluster 3: 4:30-5:00 Consume 15 more oz

Cluster 4: 7:00-7:30 Consume final 10 oz

Total Intake: 60 oz, plus sips for bedtime pills

OUTPUT

Void: Reliable urge 60-90 mins later

Possibly a 2nd void within the next 60 mins

Void: 1-2 times in next 60-120 minutes

Void: next 60-120 minutes

Void :next 60-120 mins

Final void: Bedtime

Total voids: generally 5-8, depending on actual intake

Kathy E. Golic, PT is a physical therapist at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in North Bend, Washington.

From a very young age, I had the passion to be a Physical Therapist, but it was only recently that a hidden passion was revealed, Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy. I graduated from Stockton University with my BS in Biology in 2007 and Doctorate of Physical Therapy in 2009. I have a history of pelvic health issues and had felt extremely uneasy about going to pelvic floor continuing education, so I focused on other areas early in my career like pediatrics, adult neuro, acute care, and wound care.

As a little girl, I dealt with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction due to tight pelvic floor muscles, with frequent urinary tract infections, and an overactive bladder. Then as a teen, I had pain with penetration, from tampons to speculums and later during sexual activities. Luckily, I was treated by a Pelvic Health Specialist who helped me to have a full and active lifestyle without pain and irritation but it took me a long time to find help with the right provider. I have experienced pregnancy (and most of the common complications including morning sickness, preterm labor & pelvic pain) and complicated childbirth that ended in a cesarean section. My daughter also experiences many of the common pediatric pelvic floor issues like constipation, post-void dribbling, and bedwetting.

When a coworker of mine was looking for someone to help her with our company’s Pelvic Floor program, I found the personal courage to go and take Pelvic Floor Level 1 with Herman & Wallace. I had always had the interest and the personal experiences, but I needed to find the right situation to delve into it all; enter Herman & Wallace. I cannot overstate how welcomed, safe, educated, and reassured I felt beginning my journey with Lila Abbate and Dustienne Miller. I signed up for my next course while still attending that first course, and there was no limit to the number of continuing education courses from Herman and Wallace I wished to attend over the next two years. Herman and Wallace had woken up a passion in me I didn’t even know I yearned for. I wanted to know anything, everything about pelvic floors. The next logical step to assure myself and my patients that I was an advanced practitioner in this area was to take my PRPC which I completed in May 2019.

My pelvic floor bestie, who happens to be someone I met on my first day of PF1, convinced me I was ready to be a Teaching Assistant in March of 2020. It was an amazing experience to be able to be the moral support for that next cohort of pelvic health practitioners and to share my years of tips, tricks, and experience. COVID shut things down for a bit the weekend after, but later in the year when Herman & Wallace was looking for TAs to help with their newly formatted hybrid classes, I was ready to lend a hand. Each time I TA, I learn new things and get to pass skills I have mastered on to new practitioners.

Herman & Wallace is wonderful at creating continuing education classes. I love their organization, adaptation, and ability to prepare practitioners to leave a course on Sunday and start using their new skills on Monday. Since taking a class with them, while other continuing education courses from other companies have provided information and opportunities, I find myself constantly comparing the field to Herman & Wallace, and I always find my way back to the company that has truly given me a renewed reason to love what I do.

Mora A Pluchino, PT, DPT, PRPC is a New Jersey based physical therapist and owns her own PT clinic, Practically Perfect Physical Therapy. She is a senior TA for H&W and can be found TAing courses in her area.

Fears about treating men’s health conditions are limiting access to care or are creating potential for harm in the field of pelvic health. Many cisgender women (women whose gender identify matches the sex likely assigned at birth) express concerns about working with cisgender men beyond a lack of knowledge about conditions related to prostate issues, urinary leakage, or genital pain. Are these fears warranted, are they fair? Rather than assert that ciswomen should simply move beyond their concerns, the field of pelvic health and the patients with whom we work may be better served by digging in and talking more openly about such fears. Following are some of the concerns or comments I have heard expressed by cisgender women within the context of treating men’s health matters:

- (Regarding palpation of the penis:) “Is that legal?”

- “I worry about being alone in a room with a man.”

- “What if he gets an erection?”

- “My husband doesn’t want me to work with other men for pelvic health stuff.”

- “I’ve never seen a man’s genitals before and I’m not comfortable with it.”

- “My religion teaches that I should not touch a man other than my husband.”

- “I don’t know what to say when men make suggestive comments.”

- “My supervisor is forcing me to do this work with men when I don’t want to.”

- “I only treat them in side lying because then I don’t have to see their stuff.”

Rather than a reader making a judgement about the above comments, we should ask ourselves as a profession if the above topics have been properly addressed in our training or if we are encouraged to work through this area of professional and personal intersecting concerns. We could view the concerns expressed through the lens of providing equal care, in other words, are we discriminating against someone based on their genitals? Or through a lens of safety- is there an actual (as well as perceived) threat from a cisgender woman who is alone in a treatment room with a cisgender man? If that’s potentially true, how are we mitigating this risk? Where does the anatomical line end between personal beliefs such as “I can touch another man’s shoulder, but not perineal area”? Are we practicing ethically if we are denying access to care or providing less than comprehensive care? Is a therapist truly worried about their primary relationship by doing this work because their partner does not approve? And more importantly, can we provide needed guidance or support to address some of the above obstacles?

I commonly have the opportunity to work with men who have seen other self-identified female therapists first. Here is what I often hear:

- “I could tell that they weren’t comfortable talking to me about this issue.”

- “It didn’t seem like they knew what to do with me.”

- “I got switched over to another therapist after asking some questions about using a penile pump.”

- “I felt really shamed about my condition because they would change the subject.”

- “I called many places and they rejected seeing me because I’m a man.”

- “When I asked if they were going to examine where the pain is [genital area] they said it would be a last resort.”

- “No one ever examined me, just gave me a biofeedback sensor to put in.”

This information is not shared to shame the caring professionals in our field. What needs to happen, however, for elevating the inclusiveness of care, is a continual dialogue and recognition of the support needed to work with sensitive conditions and the vulnerabilities of both patients and providers. It is potentially harmful to reject patients based on gender, or to provide lesser care based on genitals. To further this conversation, the Institute has partnered with author and educator Leticia Nieto, who holds a degree in psychology and who wrote Beyond Inclusion, Beyond Empowerment: A Developmental Strategy to Liberate Everyone. Join Leticia and me (Holly Tanner) for our first 3-hour discussion that emphasizes talking, feeling, and thinking through some of the above concerns and challenges. The class will focus on discussion more than lecture, and will aim to provide a space within which we can speak openly about how to move forward with the goal of improving comfort when working with men’s health issues and improving access to much needed pelvic health care. Note: this class is welcoming to all people with any gender identification, however, the emphasis will be on the topics discussed in this post.

Rachna Mehta, PT, DPT, CIMT, OCS, PRPC is the author and instructor of the new Acupressure for Pelvic Health course. She is Board certified in Orthopedics, is a Certified Integrated Manual Therapist and is also a Herman and Wallace certified Pelvic Rehab Practitioner. An alumni of Columbia University, Rachna brings a wealth of experience to her physical therapy practice with a special interest in complex orthopedic patients with bowel, bladder and sexual health issues. Rachna has a personal interest in various eastern holistic healing traditions and she noticed that many of her chronic pain patients were using complementary health care approaches including Acupuncture and Yoga. Building on her orthopedic and pelvic health experience, Rachna trained with renowned teachers in Acupressure and Yin Yoga. Her course Acupressure for Pelvic Health brings a unique evidence-based approach and explores complementary medicine as a powerful tool for holistic management of the individual as a whole focusing on the physical, emotional and energy body. Rachna is a member of the American Physical Therapy Association and a member of APTA’s Pelvic Health section.

Rachna Mehta, PT, DPT, CIMT, OCS, PRPC is the author and instructor of the new Acupressure for Pelvic Health course. She is Board certified in Orthopedics, is a Certified Integrated Manual Therapist and is also a Herman and Wallace certified Pelvic Rehab Practitioner. An alumni of Columbia University, Rachna brings a wealth of experience to her physical therapy practice with a special interest in complex orthopedic patients with bowel, bladder and sexual health issues. Rachna has a personal interest in various eastern holistic healing traditions and she noticed that many of her chronic pain patients were using complementary health care approaches including Acupuncture and Yoga. Building on her orthopedic and pelvic health experience, Rachna trained with renowned teachers in Acupressure and Yin Yoga. Her course Acupressure for Pelvic Health brings a unique evidence-based approach and explores complementary medicine as a powerful tool for holistic management of the individual as a whole focusing on the physical, emotional and energy body. Rachna is a member of the American Physical Therapy Association and a member of APTA’s Pelvic Health section.

According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), a branch of NIH, pain is the most common reason for seeking medical care1. Over the last several decades there has been an increasing interest in safe and efficacious treatment options as our healthcare system faces a crisis of pills and opioid use. Among complementary medicine approaches, Acupressure has come forth as an effective non-pharmacologic therapeutic modality for symptom management.

Acupressure is widely considered to be a noninvasive, low cost, and efficient complementary alternative medical approach to alleviate pain. It is easy to do anywhere at any time and empowers the individual by putting their health in their hands. Acupressure involves the application of pressure to points located along the energy meridians of the body. These acupoints are thought to exert certain psychologic, neurologic, and immunologic effects to balance optimum physiologic and psychologic functions2. Acupressure can be used for alleviating anxiety, stress and treating a variety of pelvic health conditions including Chronic Pelvic Pain, Dysmenorrhea, Constipation, digestive disturbances and urinary dysfunctions to name a few.

Acupressure uses the same points as Acupuncture; however, it is a very active practice in that we can teach our patients potent acupressure points as part of a wellness self-care regimen to manage their pain, anxiety and stress in addition to traditional physical therapy interventions. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) believes in Meridian theory and energy channels which are connected to the function of the visceral organs. There is emerging scientific evidence of Acupoints transmitting energy through interstitial connective tissue with potentially powerful integrative applications through multiple systems.

Acupressure has also been used with various types of mindfulness and breathing practices including Qigong and Yoga. Yoga is an umbrella term for various physical, mental, and spiritual practices originating in ancient India, Hath Yoga being the most popular form of Yoga in western society. Yin Yoga, a derivative of Hath Yoga, is a much calmer meditative practice that uses seated and supine postures, held three to five minutes while maintaining deep breathing. Its focus on calmness and mindfulness makes Yin Yoga a tool for relaxation and stress coping, thereby improving psychological health3. Yin Yoga facilitates energy flow through the meridians and can be used for stimulating acupressure points along specific meridian and energy channels bringing the body to its physiological resting state.

As Pelvic health rehabilitation specialists, we are uniquely trained to combine our orthopedic skills with mindfulness based holistic interventions to improve the quality of life of our patients. We can empower our patients to recognize the mind-body-energy interconnections and how they affect multiple systems, giving them the tools and self-care regimens to live healthier pain free lives. Please join me on this evidence-based journey of holistic healing and empowerment as we explore Acupressure and Yin Yoga as powerful tools in the realm of energy medicine to complement our best evidence-based practices.

1. Pain: Considering Complementary Approaches published by National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.2019.

2. Monson E, Arney D, Benham B, et al. Beyond Pills: Acupressure Impact on Self-Rated Pain and Anxiety Scores. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(5):517-521.

3. Daukantaitė D, Tellhed U, Maddux RE, Svensson T, Melander O. Five-week yin yoga-based interventions decreased plasma adrenomedullin and increased psychological health in stressed adults: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(7).

Pauline H. Lucas, PT, DPT, WCS, NBC-HWC joins the Herman & Wallace faculty with her new course, Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals. The course launches January 2021 and discusses the impact of chronic stress on health and wellbeing, and the latest research on the benefits of mindfulness training for both patients and healthcare providers. The following comes from Pauline, who hopes you will join her for her course.

Pauline H. Lucas, PT, DPT, WCS, NBC-HWC joins the Herman & Wallace faculty with her new course, Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals. The course launches January 2021 and discusses the impact of chronic stress on health and wellbeing, and the latest research on the benefits of mindfulness training for both patients and healthcare providers. The following comes from Pauline, who hopes you will join her for her course.

As an integrative physical therapist treating people with pelvic pain, digestive issues, headaches, and various persistent pain conditions, I council my patients on strategies to reduce a chronically activated stress response (sympathetic dominance). Many of them are living stressful lives, and their medical condition can be an additional stressor. I share with them that by reducing their stress level and improving their overall awareness of what makes them feel better and worse, they may affect their condition in a positive way. When I ask if they have any experience with meditation, I often get the response: “Oh I tried that many years ago and I’m really bad at it; I just can’t meditate.” When I ask them to explain a bit more, they tell me that their mind is always super busy, they are always thinking, and when they try to stop the thoughts during meditation, it doesn’t work.

This is when I explain one of the essential concepts of meditation: It’s okay to have thoughts. In fact, it’s completely normal to become more aware of the busy thoughts when you first sit down to meditate. The trick is to allow the thoughts to be there, and at the same time keeping awareness with the focus of the meditation practice (i.e., the breath, a mantra, etc.). When we don’t resist the thoughts, the mind naturally gradually calms down, resulting in fewer and calmer thoughts. This is when I typically see relief on my patient’s face when they realize they may not be a bad meditator after all, and they are often willing to give the practice another try.

To learn more about using mindfulness and meditation in your personal life and in patient care, please join our 1 day virtual course Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./