This is Part 2 of Tuesday's, April 27, 2021, blog Misbehaving Bladders and Cluster Drinking - A Novel Approach, Part 1.

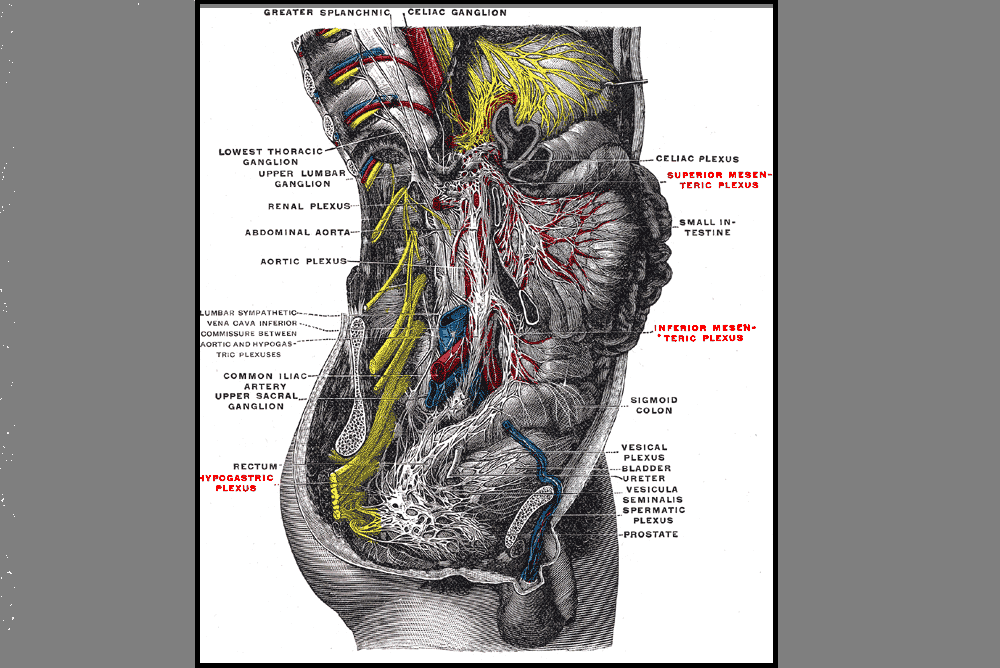

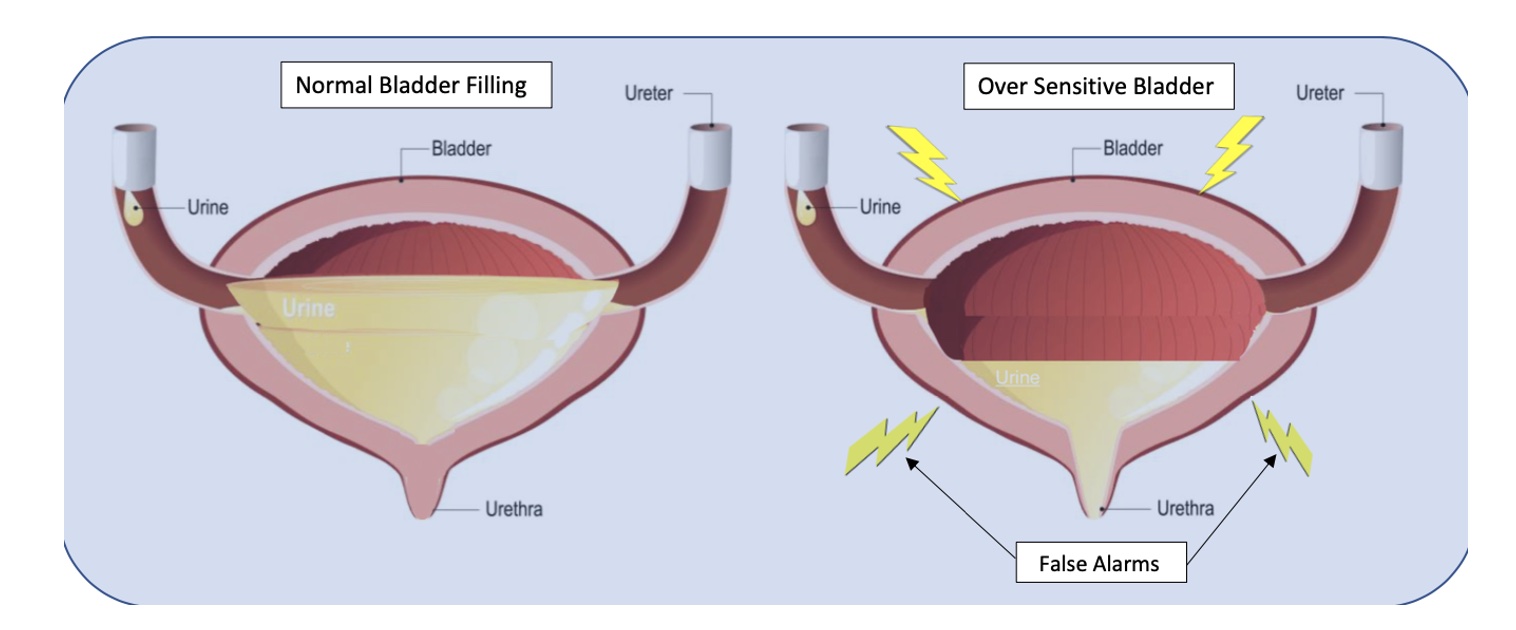

Bladder capacity ranges from around 400-500ml (13-16 oz). The use of a measuring cup or water bottle can be very helpful to teach this concept. We certainly don’t have to strive for a full bladder volume, but it is important to illustrate that 2-3 ounces are in fact “just in case” voids. I explain to patients that in situations of overactive or irritated bladders, the receptors in their bladder walls are hypersensitive and sending “false alarm” messages when only a small amount of urine is present. The kidneys are always active and refilling the bladder, so it will never be totally empty per se, therefore it must be desensitized and retrained to be a viable, reliable, and reasonably comfortable storage vessel.

With the Cluster Drinking Approach, it is important to try and drink the fluid in a short enough period of time to ensure an increased rate of bladder filling for this to be effective, but you must be careful to monitor the bladder irritability with the training. A fuller bladder will experience more pressure, but this also helps with urine flow during voids. We then embark on this process of retraining and using their bladder diaries to help us with detective work to determine optimal amounts of fluid intake in each cluster and the optimal timing of fluid intake, number of clusters, etc. for their daily schedules. It may take some time to get used to the new habits. It can be hard for some patients who are used to sipping on their water bottle all day long, and they can feel dehydrated. This is a habit and learned response and can be retrained with some gradual investment in the process. Once patients experience the rewarding outcomes, they are usually willing to make the changes.

Based on diary findings, we modify types of fluids as necessary, my motto being: minimal disruption to achieve desired results. Why give up coffee and all favorite beverages if not necessary? Sometimes making modifications on timing and amount of intake works just fine, other times we tweak the beverage types. I also teach and integrate urge suppression strategies (USS) as well, to help with the process of retraining; and of course, address breathing, pelvic floor dysfunctions, connective tissue restrictions, and chronic constipation, but the variable which sets this approach apart is the cluster drinking.

According to Washington state urogynecologist Elizabeth A. Miller, MD FPMRS, a practitioner at Overlake and Swedish Medical Centers, the Cluster Drinking Approach works similarly to some OAB medications in training your bladder to hold more urine. She endorses the Cluster Drinking Approach as a viable first-line treatment option since it works naturally without harmful side effects. Results are often profound and rapid even for folks who have been struggling with these bladder issues for years. Likewise, leaking issues tend to diminish as the bladder training is mastered. Patients can structure riskier activities around this cluster program, i.e. plan their Zumba after cluster intake and output. The same goes for major outings where one will not be near a bathroom. Even my constipation patients have benefitted due to a more reliable intake of adequate fluid.

Nocturia is a bit of a different situation because of the role of kidney hormones, but I have found this approach to be quite effective for many patients whose lives and sleep are impacted by this problem. The Cluster Drinking Approach helps these patients to structure their fluid intake during daytime hours, and I teach them to heed the 1st overnight urge if it is within 2-3 hours after going to sleep. Then if they awaken again, I coach them to use the mantra “the bladder is a storage vessel”, analyze their last intake and output, and permit themselves to use the Urge Suppression Strategies, and go back to sleep without worrying that their bladder will explode. The other good news is after their bladders (and brains) are “retrained”, and you have done your PT magic, they can often return to more natural drinking patterns without negative consequences.

Fun Fact: Even Did you know that under anesthesia the amazing expandable bladder can hold over 1 liter?!

Kathy E. Golic, PT is a physical therapist at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Washington.

There have been many constructive blogs about managing symptoms of overactive and misbehaving bladders, but I want to share an approach I have been using successfully for many years. Not only does this approach work for the majority of my patients in terms of addressing urgency, frequency, and urine leakage, but results are often quite rapid. After treating patients with modest success for many years with the traditional treatment approaches and noting that too often patients would plateau or results were just not effective or fast enough, I created my own approach to help these patients. I call it Cluster Drinking Approach and explain to my patients that cluster drinking begets cluster voiding.

When folks sip fluid, even water, all day long, it is hard for them to know when their bladder is full enough to warrant a trip to the bathroom. In patients with oversensitive or irritated bladders, the sensory receptors in the bladder wall are agitated and so often send false, unreliable signals,

when there is not much urine present. So they continue to struggle with urges and frequency and sometimes urine leakage. However, when they divide their fluid intake into 3-4, or sometimes even 5 or more, “clusters” then their bladders fill more predictably. They can sense it, and based on timing and amount of intake, they can reliably determine when the urges are accurate.

This requires a mindful and analytical approach to help retrain their bladders. The amount of intake and number of clusters are selected based on the level of bladder irritability, the patient’s schedule, as well as their weight, age, and level of anxiety. The variables can be modified according to their daily schedules, and their progress. Coupled with my mantra, “The bladder is a storage vessel, it is meant to hold urine!” this approach has been life-changing for many patients, and often in just a few visits!

Here is an example to illustrate what this might look like based on 60 fluid oz of daily intake. And important to share this pearl...In case you did not know...the adage of 8 glasses of 8 ounces of water was not based on research. So this will be quite individualized.

INTAKE

Cluster 1: 7:00 am-7:30am Consume 20 oz of fluid

Cluster 2: 11:30-12:00 Consume next 15 oz

Cluster 3: 4:30-5:00 Consume 15 more oz

Cluster 4: 7:00-7:30 Consume final 10 oz

Total Intake: 60 oz, plus sips for bedtime pills

OUTPUT

Void: Reliable urge 60-90 mins later

Possibly a 2nd void within the next 60 mins

Void: 1-2 times in next 60-120 minutes

Void: next 60-120 minutes

Void :next 60-120 mins

Final void: Bedtime

Total voids: generally 5-8, depending on actual intake

Kathy E. Golic, PT is a physical therapist at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in North Bend, Washington.

From a very young age, I had the passion to be a Physical Therapist, but it was only recently that a hidden passion was revealed, Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy. I graduated from Stockton University with my BS in Biology in 2007 and Doctorate of Physical Therapy in 2009. I have a history of pelvic health issues and had felt extremely uneasy about going to pelvic floor continuing education, so I focused on other areas early in my career like pediatrics, adult neuro, acute care, and wound care.

As a little girl, I dealt with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction due to tight pelvic floor muscles, with frequent urinary tract infections, and an overactive bladder. Then as a teen, I had pain with penetration, from tampons to speculums and later during sexual activities. Luckily, I was treated by a Pelvic Health Specialist who helped me to have a full and active lifestyle without pain and irritation but it took me a long time to find help with the right provider. I have experienced pregnancy (and most of the common complications including morning sickness, preterm labor & pelvic pain) and complicated childbirth that ended in a cesarean section. My daughter also experiences many of the common pediatric pelvic floor issues like constipation, post-void dribbling, and bedwetting.

When a coworker of mine was looking for someone to help her with our company’s Pelvic Floor program, I found the personal courage to go and take Pelvic Floor Level 1 with Herman & Wallace. I had always had the interest and the personal experiences, but I needed to find the right situation to delve into it all; enter Herman & Wallace. I cannot overstate how welcomed, safe, educated, and reassured I felt beginning my journey with Lila Abbate and Dustienne Miller. I signed up for my next course while still attending that first course, and there was no limit to the number of continuing education courses from Herman and Wallace I wished to attend over the next two years. Herman and Wallace had woken up a passion in me I didn’t even know I yearned for. I wanted to know anything, everything about pelvic floors. The next logical step to assure myself and my patients that I was an advanced practitioner in this area was to take my PRPC which I completed in May 2019.

My pelvic floor bestie, who happens to be someone I met on my first day of PF1, convinced me I was ready to be a Teaching Assistant in March of 2020. It was an amazing experience to be able to be the moral support for that next cohort of pelvic health practitioners and to share my years of tips, tricks, and experience. COVID shut things down for a bit the weekend after, but later in the year when Herman & Wallace was looking for TAs to help with their newly formatted hybrid classes, I was ready to lend a hand. Each time I TA, I learn new things and get to pass skills I have mastered on to new practitioners.

Herman & Wallace is wonderful at creating continuing education classes. I love their organization, adaptation, and ability to prepare practitioners to leave a course on Sunday and start using their new skills on Monday. Since taking a class with them, while other continuing education courses from other companies have provided information and opportunities, I find myself constantly comparing the field to Herman & Wallace, and I always find my way back to the company that has truly given me a renewed reason to love what I do.

Mora A Pluchino, PT, DPT, PRPC is a New Jersey based physical therapist and owns her own PT clinic, Practically Perfect Physical Therapy. She is a senior TA for H&W and can be found TAing courses in her area.

Fears about treating men’s health conditions are limiting access to care or are creating potential for harm in the field of pelvic health. Many cisgender women (women whose gender identify matches the sex likely assigned at birth) express concerns about working with cisgender men beyond a lack of knowledge about conditions related to prostate issues, urinary leakage, or genital pain. Are these fears warranted, are they fair? Rather than assert that ciswomen should simply move beyond their concerns, the field of pelvic health and the patients with whom we work may be better served by digging in and talking more openly about such fears. Following are some of the concerns or comments I have heard expressed by cisgender women within the context of treating men’s health matters:

- (Regarding palpation of the penis:) “Is that legal?”

- “I worry about being alone in a room with a man.”

- “What if he gets an erection?”

- “My husband doesn’t want me to work with other men for pelvic health stuff.”

- “I’ve never seen a man’s genitals before and I’m not comfortable with it.”

- “My religion teaches that I should not touch a man other than my husband.”

- “I don’t know what to say when men make suggestive comments.”

- “My supervisor is forcing me to do this work with men when I don’t want to.”

- “I only treat them in side lying because then I don’t have to see their stuff.”

Rather than a reader making a judgement about the above comments, we should ask ourselves as a profession if the above topics have been properly addressed in our training or if we are encouraged to work through this area of professional and personal intersecting concerns. We could view the concerns expressed through the lens of providing equal care, in other words, are we discriminating against someone based on their genitals? Or through a lens of safety- is there an actual (as well as perceived) threat from a cisgender woman who is alone in a treatment room with a cisgender man? If that’s potentially true, how are we mitigating this risk? Where does the anatomical line end between personal beliefs such as “I can touch another man’s shoulder, but not perineal area”? Are we practicing ethically if we are denying access to care or providing less than comprehensive care? Is a therapist truly worried about their primary relationship by doing this work because their partner does not approve? And more importantly, can we provide needed guidance or support to address some of the above obstacles?

I commonly have the opportunity to work with men who have seen other self-identified female therapists first. Here is what I often hear:

- “I could tell that they weren’t comfortable talking to me about this issue.”

- “It didn’t seem like they knew what to do with me.”

- “I got switched over to another therapist after asking some questions about using a penile pump.”

- “I felt really shamed about my condition because they would change the subject.”

- “I called many places and they rejected seeing me because I’m a man.”

- “When I asked if they were going to examine where the pain is [genital area] they said it would be a last resort.”

- “No one ever examined me, just gave me a biofeedback sensor to put in.”

This information is not shared to shame the caring professionals in our field. What needs to happen, however, for elevating the inclusiveness of care, is a continual dialogue and recognition of the support needed to work with sensitive conditions and the vulnerabilities of both patients and providers. It is potentially harmful to reject patients based on gender, or to provide lesser care based on genitals. To further this conversation, the Institute has partnered with author and educator Leticia Nieto, who holds a degree in psychology and who wrote Beyond Inclusion, Beyond Empowerment: A Developmental Strategy to Liberate Everyone. Join Leticia and me (Holly Tanner) for our first 3-hour discussion that emphasizes talking, feeling, and thinking through some of the above concerns and challenges. The class will focus on discussion more than lecture, and will aim to provide a space within which we can speak openly about how to move forward with the goal of improving comfort when working with men’s health issues and improving access to much needed pelvic health care. Note: this class is welcoming to all people with any gender identification, however, the emphasis will be on the topics discussed in this post.

Rachna Mehta, PT, DPT, CIMT, OCS, PRPC is the author and instructor of the new Acupressure for Pelvic Health course. She is Board certified in Orthopedics, is a Certified Integrated Manual Therapist and is also a Herman and Wallace certified Pelvic Rehab Practitioner. An alumni of Columbia University, Rachna brings a wealth of experience to her physical therapy practice with a special interest in complex orthopedic patients with bowel, bladder and sexual health issues. Rachna has a personal interest in various eastern holistic healing traditions and she noticed that many of her chronic pain patients were using complementary health care approaches including Acupuncture and Yoga. Building on her orthopedic and pelvic health experience, Rachna trained with renowned teachers in Acupressure and Yin Yoga. Her course Acupressure for Pelvic Health brings a unique evidence-based approach and explores complementary medicine as a powerful tool for holistic management of the individual as a whole focusing on the physical, emotional and energy body. Rachna is a member of the American Physical Therapy Association and a member of APTA’s Pelvic Health section.

Rachna Mehta, PT, DPT, CIMT, OCS, PRPC is the author and instructor of the new Acupressure for Pelvic Health course. She is Board certified in Orthopedics, is a Certified Integrated Manual Therapist and is also a Herman and Wallace certified Pelvic Rehab Practitioner. An alumni of Columbia University, Rachna brings a wealth of experience to her physical therapy practice with a special interest in complex orthopedic patients with bowel, bladder and sexual health issues. Rachna has a personal interest in various eastern holistic healing traditions and she noticed that many of her chronic pain patients were using complementary health care approaches including Acupuncture and Yoga. Building on her orthopedic and pelvic health experience, Rachna trained with renowned teachers in Acupressure and Yin Yoga. Her course Acupressure for Pelvic Health brings a unique evidence-based approach and explores complementary medicine as a powerful tool for holistic management of the individual as a whole focusing on the physical, emotional and energy body. Rachna is a member of the American Physical Therapy Association and a member of APTA’s Pelvic Health section.

According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), a branch of NIH, pain is the most common reason for seeking medical care1. Over the last several decades there has been an increasing interest in safe and efficacious treatment options as our healthcare system faces a crisis of pills and opioid use. Among complementary medicine approaches, Acupressure has come forth as an effective non-pharmacologic therapeutic modality for symptom management.

Acupressure is widely considered to be a noninvasive, low cost, and efficient complementary alternative medical approach to alleviate pain. It is easy to do anywhere at any time and empowers the individual by putting their health in their hands. Acupressure involves the application of pressure to points located along the energy meridians of the body. These acupoints are thought to exert certain psychologic, neurologic, and immunologic effects to balance optimum physiologic and psychologic functions2. Acupressure can be used for alleviating anxiety, stress and treating a variety of pelvic health conditions including Chronic Pelvic Pain, Dysmenorrhea, Constipation, digestive disturbances and urinary dysfunctions to name a few.

Acupressure uses the same points as Acupuncture; however, it is a very active practice in that we can teach our patients potent acupressure points as part of a wellness self-care regimen to manage their pain, anxiety and stress in addition to traditional physical therapy interventions. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) believes in Meridian theory and energy channels which are connected to the function of the visceral organs. There is emerging scientific evidence of Acupoints transmitting energy through interstitial connective tissue with potentially powerful integrative applications through multiple systems.

Acupressure has also been used with various types of mindfulness and breathing practices including Qigong and Yoga. Yoga is an umbrella term for various physical, mental, and spiritual practices originating in ancient India, Hath Yoga being the most popular form of Yoga in western society. Yin Yoga, a derivative of Hath Yoga, is a much calmer meditative practice that uses seated and supine postures, held three to five minutes while maintaining deep breathing. Its focus on calmness and mindfulness makes Yin Yoga a tool for relaxation and stress coping, thereby improving psychological health3. Yin Yoga facilitates energy flow through the meridians and can be used for stimulating acupressure points along specific meridian and energy channels bringing the body to its physiological resting state.

As Pelvic health rehabilitation specialists, we are uniquely trained to combine our orthopedic skills with mindfulness based holistic interventions to improve the quality of life of our patients. We can empower our patients to recognize the mind-body-energy interconnections and how they affect multiple systems, giving them the tools and self-care regimens to live healthier pain free lives. Please join me on this evidence-based journey of holistic healing and empowerment as we explore Acupressure and Yin Yoga as powerful tools in the realm of energy medicine to complement our best evidence-based practices.

1. Pain: Considering Complementary Approaches published by National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.2019.

2. Monson E, Arney D, Benham B, et al. Beyond Pills: Acupressure Impact on Self-Rated Pain and Anxiety Scores. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(5):517-521.

3. Daukantaitė D, Tellhed U, Maddux RE, Svensson T, Melander O. Five-week yin yoga-based interventions decreased plasma adrenomedullin and increased psychological health in stressed adults: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(7).

Pauline H. Lucas, PT, DPT, WCS, NBC-HWC joins the Herman & Wallace faculty with her new course, Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals. The course launches January 2021 and discusses the impact of chronic stress on health and wellbeing, and the latest research on the benefits of mindfulness training for both patients and healthcare providers. The following comes from Pauline, who hopes you will join her for her course.

Pauline H. Lucas, PT, DPT, WCS, NBC-HWC joins the Herman & Wallace faculty with her new course, Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals. The course launches January 2021 and discusses the impact of chronic stress on health and wellbeing, and the latest research on the benefits of mindfulness training for both patients and healthcare providers. The following comes from Pauline, who hopes you will join her for her course.

As an integrative physical therapist treating people with pelvic pain, digestive issues, headaches, and various persistent pain conditions, I council my patients on strategies to reduce a chronically activated stress response (sympathetic dominance). Many of them are living stressful lives, and their medical condition can be an additional stressor. I share with them that by reducing their stress level and improving their overall awareness of what makes them feel better and worse, they may affect their condition in a positive way. When I ask if they have any experience with meditation, I often get the response: “Oh I tried that many years ago and I’m really bad at it; I just can’t meditate.” When I ask them to explain a bit more, they tell me that their mind is always super busy, they are always thinking, and when they try to stop the thoughts during meditation, it doesn’t work.

This is when I explain one of the essential concepts of meditation: It’s okay to have thoughts. In fact, it’s completely normal to become more aware of the busy thoughts when you first sit down to meditate. The trick is to allow the thoughts to be there, and at the same time keeping awareness with the focus of the meditation practice (i.e., the breath, a mantra, etc.). When we don’t resist the thoughts, the mind naturally gradually calms down, resulting in fewer and calmer thoughts. This is when I typically see relief on my patient’s face when they realize they may not be a bad meditator after all, and they are often willing to give the practice another try.

To learn more about using mindfulness and meditation in your personal life and in patient care, please join our 1 day virtual course Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals.

Parkinson disease is the second most common neurologic disorder. When most people think about people with Parkinson disease, they think about stooped posture, shuffling gait, slow and rigid movement, balance difficulties and tremoring. Often these motor symptoms are the main target of pharmacological treatments with neurologists and many experience positive functional gains. Non-motor symptoms, however, can be more disabling than the motor symptoms and have significant adverse effects on the quality of life in people with Parkinson disease.

Pelvic rehabilitation specialists have a unique opportunity to step in and help these individuals improve their quality of life and many neurologists are unaware of the benefits our services could provide for their patients.

Please join me in an exciting dive into understanding the physiology of how Parkinson disease affects a person’s pelvic health and develop your skills to effectively assess and develop treatment plans to change the life of these individuals.

Seppi, K., Ray Chaudhuri, K., Coelho, M., Fox, S. H., Katzenschlager, R., Perez Lloret, S., ... & Hametner, E. M. (2019). Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease—an evidence‐based medicine review. Movement Disorders, 34(2), 180-198.

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT, along with Frank J Ciuba DPT, MS, is the author and instructor for a new course on osteoporisis that is launching remotely this month. Join Deb in Osteoporosis Management: A Comprehensive Approach for Healthcare Professionals!

Osteoporosis is a disease of increasingly porous bones that are at greater risk for fracture. The normal “bone remodeling” of breaking down and building up bone as we age is out of balance. Similar to a bank account with withdrawals outpacing deposits, as time goes on there is more breaking down than building back up. This leaves the bone more vulnerable for fracture.

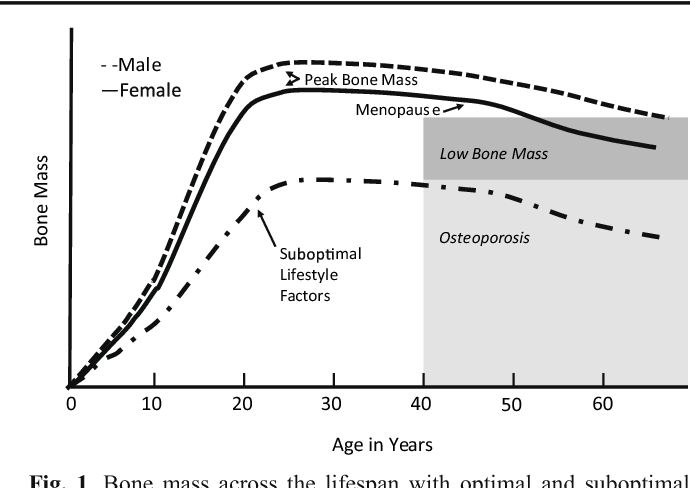

We tend to think of Osteoporosis as an old person’s disease and in fact age is certainly a risk factor. We see a sharp decline in bone density the first few years following menopause; a withdrawal from the “bone bank account.” But let me share a startling statistic. At the age of 20 we have 98% of the bone density we will ever achieve. We achieve Peak Bone Mass by age thirty when our bones have reached their maximum strength and density.

Factors affecting Peak Bone Mass include both Non-modifiable and Modifiable. Among the non-modifiable factors are gender (peak bone mass is higher in men), race (peak bone mass is higher in African Americans), and hormonal factors (early onset of menstruation and use of oral contraceptives tend to have higher peak bone mass). A family history of osteoporosis is another important factor.

Modifiable factors include nutrition (adequate calcium in the diets of young people), physical activity during the early years (specifically weight bearing and resistance exercises). Poor lifestyle behaviors (smoking, high alcohol intake, and sedentary lifestyle) have all been linked to low bone density in adolescents.

The American Physical Therapy Association website includes a section on “Container Baby Syndrome” (CBS). CBS is the name used to describe a range of physical, cognitive, and developmental conditions caused by a baby or infant spending too much time in containers such as baby carriers, strollers, and Bumpo seats. Bone mass can certainly be affected by reduced movement and weight bearing activities. Due to the SIDS scare, many young parents are fearful of allowing their children to spend time on their abdomens. Educate and share the “Supine to Sleep, Prone to Play” mantra.

The graph below shows a comparison of the Peak Bone Mass of males to females and to individuals with suboptimal lifestyle factors. You can see that the suboptimal group never catches up and enters the osteoporosis stage at around age 40.

According to the Department of Human Services “Osteoporosis is a pediatric disease with geriatric consequences. Peak bone mass is built during our first three decades. Failure to build strong bones during childhood and adolescent years manifests in fractures later in life.”

What can we do?

• Start early: Encourage young children (and their parents) to move more and sit less.

• Spread the word: Speak to Young Mothers’ Clubs, Girl Scout Troops; anywhere to influence adolescent and teens about the importance of proper exercise and good nutrition.

• Write a blog: Share this information in newspapers, social media, and on your website. Get the word out! Because the bones of our future generation depend on it.

NIH Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center

Department of Human Services

American Physical Therapy Association

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC is the author and presenter of the new Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation course, and she is the co-author of the Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab course. She is a certified LSVT (Lee Silverman) provider and faculty member, and is a trained PWR! (Parkinson’s Wellness Recovery) provider, both focusing on intensive, amplitude and neuroplasticity based exercise programs for people with Parkinson disease. Erica partners with the Wisconsin Parkinson Association (WPA) as a support group and event presenter as well as author in their publication, The Network. Erica has taken a special interest in the unique pelvic floor, bladder, bowel and sexual health issues experienced by individuals diagnosed with Parkinson disease.

The pharmacologic management of non-motor autonomic dysfunction, including urinary, bowel, and sexual health impairments, is often ineffective, not supported by adequate research, or causes intolerable side effects for people with Parkinson disease. In a recent article titled Update on Treatments for Nonmotor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease – An Evidence-Based Medicine Review Seppi, K, et al., 2019, the authors state that “before attempting any [pharmacological] treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms, urinary tract infections, prostate disease in men, and pelvic floor disease in women should be ruled out.” It is rare to see a mention of pelvic floor within the literature that addresses helping people with Parkinson disease.

Pelvic rehabilitation specialists have a unique opportunity to step in and help these individuals improve their quality of life and many neurologists are unaware of the benefits our services could provide for their patients. Please join me in an exciting dive into understanding the physiology of how Parkinson disease affects a person’s pelvic health and develop your skills to effectively assess and develop treatment plans to change the life of these individuals.

Seppi, K., Ray Chaudhuri, K., Coelho, M., Fox, S. H., Katzenschlager, R., Perez Lloret, S., ... & Hametner, E. M. (2019). Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease—an evidence‐based medicine review. Movement Disorders, 34(2), 180-198

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT is teaming up with Frank J Ciuba DPT, MS to create a new course called Osteoporosis Management: A Comprehensive Approach for Healthcare Professionals! This new course is launching remotely this July 25-26, 2020, and it emphasizes visual imagery cues which leads to enhanced performance for patients. Both course authors are trained by Sara Meeks, and have adapted her method to create this updated, evidence-based course on osteoporosis management.

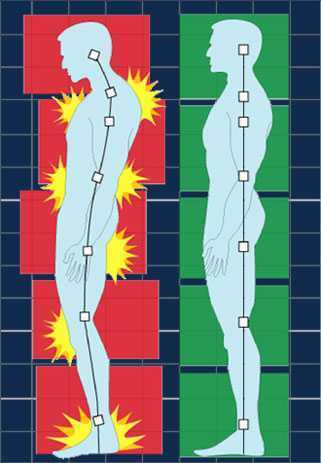

How many times have you told your patients to stand up straight and stop looking down while walking? How’d that work out? Probably not so good. At best you may have noticed a temporary correction only for the patient to return to the formerly mentioned poor posture. We know that balance is affected by alignment of our trunk and spine. 1 Everyone needs to avoid falls but it’s particularly important with osteoporosis patients due to bone fragility.

We want our patients not only to move, but to move with optimal alignment. According to Fritz, et al 2 in the vhitepaper: “Walking Speed: The Sixth Vital Sign”, walking is a complex functional activity. Our ability to influence motor control, muscle performance, sensory and perceptual function, endurance and habitual activity level can result in a more efficient and safer gait.

We want our patients not only to move, but to move with optimal alignment. According to Fritz, et al 2 in the vhitepaper: “Walking Speed: The Sixth Vital Sign”, walking is a complex functional activity. Our ability to influence motor control, muscle performance, sensory and perceptual function, endurance and habitual activity level can result in a more efficient and safer gait.

Visual imagery cuing had been popular in the sports world for decades. By changing one or two words, physical performance has been shown to improve. 3 In a study involving standing long jump, Wu et al instructed undergraduate students to either “Jump as far as you can and think about extending your legs” (internal focus) or “Jump as far as you can and think about jumping as close to the green target as possible” (external focus). The external focus group jumped 10% farther. Lohse et al 4 and Zachry et al 5 surmised that an external focus reduces the "noise" in the motor system which affects muscular tension and optimal function.

It Starts with Posture

Before you can expect your patients to walk well, they have to stand well- stability before mobility. Assess their posture from all angles and determine where to start. One visual image may change a host of problems. A common postural fault, “slumping” is seen as forward head, increased thoracic kyphosis accompanied with either lumbar hyper or hypo lordosis. Your goal is to get the optimal alignment image that you have in your mind……. into their body.

Most people think in pictures rather than words. 6 Yet the medical industry uses words to communicate. Often we say, “Don’t slouch. Don’t look down.” Telling your patient what not to do is not helpful. Our brain hears the words, “Slouch or look down.” We don’t discern the negative. If I say to you, “Don’t think of a pink elephant,” what does your mind see? How can you not see a pink elephant?

Below are five common visual cues to improve a patient’s posture in standing and walking. These tend to follow the Pareto Principle. 20% of your cues work 80% of the time.

- “In standing, imagine a bungee cord running from the top of your head to the ceiling. Visualize a mother cat lifting her kitten up by the scruff of the neck.”

- “When breathing, imagine an umbrella inside your ribcage, opening up upon inhale, and closing on exhale. Breathe in all directions including into the back of your lungs as if you were filling up the sails of a sailboat.”

- “When walking, widen your collarbones as if they were arrows, shooting off the tips of your shoulders. Imagine your head is a floating balloon, gliding along above your shoulders.”

- “Pretend you are the King (or Queen) of England as you walk among your subjects. “

- “Slide your shoulder blades down toward your opposite hip pockets.”

Choose a cue and instruct your patient. Observe changes in posture, alignment, efficiency of movement, or length of step during gait. Ask your patient for feedback. “What did you notice?” Certain cues resonate more than others. Give them variety and options. The best cues are the ones they create themselves. When a patient says, “You mean like………..?” you know it’s a great cue for them. They have an intuitive understanding and relate to it which translates into their body. A patient’s response to the bungee cord cue was, “You mean like a Christmas ornament hanging from the tree?” My response? Absolutely!

While some visual cues may seem too flowery or not “medical” enough, the research is solid the impact powerful. Plus your patients love it! Visual cues are sticky. They help remind us when we’re out in the real world. Isn’t that the ultimate goal – helping patients become independent in their pursuit of health and safety?

1. Shiro Imagam, et all. Influence of spinal sagittal alignment, body balance, muscle strength, and physical ability on falling of middle-aged and elderly males. Eur Spine J. 2013 Jun;

2. Fritz S. et al White Paper: “Walking Speed: The Sixth Vital Sign” J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2009

3. Wu, et al Effect of Attentional Focus Strategies on Peak Force and Performance in the Standing Long Jump. Joun of Strength and Conditioning Research 2012

4. Lohse and Sherwood Defining the Focus of Attention: Effects of Attention on Perceived Exertion and Fatigue

5. Zachry, T et al. Increased Movement Accuracy and Reduced EMG Activity as a Result of Adopting an External Focus of Attention. Brain Research Bulletin Oct 2005

6. Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery. Franklin, Eric. Second Edition, 2012

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./