Patients who suffer severe bladder damage or bladder disease such as invasive cancer may have the entire bladder removed in a cystectomy procedure. Once the bladder is removed, a surgeon can use a portion of the patient's ileum (the final part of the small intestines) or other part of the intestine to create a pouch or reservoir to hold urine. This procedure can be done using an open surgical approach or a laparoscopic approach. Once this new pouch is attached to the ureters and to the urethra, the "new bladder" can fill and stretch to accommodate the urine. As the neobladder cannot contract, a person will use abdominal muscle contractions along with pelvic floor relaxation to empty. If a person cannot empty the bladder adequately, a catheter may need to be utilized. (A prior blog post reported on potential complications of and resources for learning about neobladder surgery.)

During the recovery from surgery, patients will wear a catheter for a few weeks while the tissues heal. Once the catheter has been removed, patients may be instructed to urinate every 2 hours, both during the day and at night. Because patients will not have the same neurological supply to alert them of bladder filling, it will be necessary to void on a timed schedule. The time between voids can be lengthened to every 3-4 hours. Night time emptying may still occur up to two times/evening. Patient recommendations following the procedure may include that patients drink plenty of fluids, eat a healthy diet, and gradually return to normal activities. Adequate fluid is important in helping to flush mucous that is in the urine. This mucous is caused by the bowel tissue used to create the neobladder, and will reduce over time.

Urinary leakage is more common at night in patients who have had the procedure, and this often improves over a period of time, even a year or two after the surgery. As pelvic rehabilitation providers, we may be offering education about healthy diet and fluid intake, pelvic and abdominal muscle health and coordination, function retraining and instruction in return to activities. In addition to having gone through a major surgical procedure, patients may also have experienced a period of radiation, other treatments, or debility that may limit their activity levels. The Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute is pleased to offer courses by faculty member Michelle Lyons in Oncology and the Pelvic Floor, Part A: Female Reproductive and Gynecologic Cancers, and Part B: Male Reproductive, Bladder, and Colorectal Cancers. If you would like to explore pelvic rehabilitation in relation to oncology issues, there is still time to register for the Part A course taking place in Torrance, California in May! If you would like to host either of these courses at your facility, let us know!

In our weekly feature section, Pelvic Rehab Report is proud to present this interview with Herman & Wallace instructor Peter Philip, PT, ScD, COMT, PRPC

How did you get started in pelvic rehab?

While treating an MD, OB-GYN, he asked me a question regarding a patient that he was treating that was suffering from dyspareunia. I’d just completed my Master's in orthopedic physical therapy and realized that there was an entire section of the body that was "full of muscles, ligaments and nerves” of which I had virtually no knowledge. This bothered me, so I began my own independent research, study and application of skills learned through continuing education, and application of what are typically considered to be ‘orthopedic’ techniques to the pelvic pain/dysfunction population. To my (continued) wonderment, the patients responded exceptionally well, and efficiently.

Who or what inspired you?

Dr. Russell Woodman and Dr. Holly Herman have provided me with the foundational skills and motivation to help and heal those patients suffering.

What have you found most rewarding in treating this patient population?

Many patients have suffered for years prior to ‘finding’ me. Many are despondent, and have given up hope for a cure; resigning themselves to a life of pain. Providing the means of restoring comfort and wellness is gratifying, rewarding and quite frankly, humbling. What an honor it is to help those that suffer regain the life that they thought they’ve lost.

What do you find more rewarding about teaching?

Having the opportunity to assist clinicians (MDs, PTs, DCs) more effectively, efficiently evaluate and treat their patients provides me with the same gratification that treating the patients myself. This, in addition to being able to help those that have not been helped attain their wellness and health they’ve been seeking, often for years.

What was it like the first time you taught a course to a group of therapists?

The first course I taught was in NYC. The air conditioning was broken, and the office had a few, small windows. The ambient temperature was upper nineties, and no breeze. Through the tortuous temperatures, and ‘first time jitters’ I persevered, and the staff were incredible hosts and provided me with guidance that I appreciate to this day!

What trends/changes are you finding in the field of pelvic rehab?

Manual medicine and non-surgical interventions are being more recognized as very viable means to address, and eliminate pain while improving biomechanics and function. Medical practitioners from all fields are consulting with specialists in the field of pelvic pain to better address their patients' suffering. We are at the forefront of interventional treatments, and patients are seeking effective means to eradicate their pain and dysfunction.

If you could get a message to all therapists about pelvic rehab, what would it be?

Review, re-read, re-learn all the anatomy, neuroanatomy, kinematics and never forget to think, think, think.

In a case report published within the past year by physical therapist Karen Litos, a detailed and thorough case study describes the therapeutic progression and outcomes for a woman with significant functional limitation due to a separation of her diastasis recti muscles. The patient in the case is described as a 32-year-old G2P2 African-American woman referred to PT at 7 weeks postpartum. Delivery occurred vaginally with epidural, no perineal tearing, and pushing time of less than an hour. Primary concerns of the patient included burning or sharp abdominal pain when lifting, standing, and walking. Uterine contractions that naturally occurred during breastfeeding also worsened the abdominal pain and caused the patient to discontinue breastfeeding. The patient furthermore reported sensations that her insides felt like they would fall out, and abdominal muscle weakness and fatigue with activity.

Although many other significant details related to history, examination and evaluation were included in the case report, I will focus on the signs, interventions, and outcomes recorded in the paper. Diastasis was measured using finger width assessment and a tape measure. (Although ultrasound is more accurate and valid, palpation of diastasis has been demonstrated to have good intra-rater reliability as used in this study. Measures for interrecti distance (IRD) at time of evaluation were 11.5 cm at the umbilicus, 8 cm above the umbilicus, and 5 cm below the umbilicus. The patient also reported pain on the visual analog scale (VAS) of 3-8/10.

Interventions in rehabilitation included, but were not limited to: instruction in wearing an abdominal binder, appropriate abdominal and trunk strengthening (promotion of efficient load transfer and avoidance of exercises that may worsen separation), biomechanics training with functional tasks such as transfers, self-bracing of abdominals, avoiding Valsalva, postural alignment and symmetrical weight-bearing strategies. Plan of care was developed as 2-3x/week for 2-3 weeks, the patient was seen for 18 visits over a four month period. Therapeutic exercise was progressed to include general hip and trunk muscle strengthening towards a goal of stability during movement. Cardiovascular training progressed to light treadmill jogging and use of an elliptical.

After 18 visits, functional goals were all met and included picking up her baby, holding her baby for 30 minutes, standing or walking for at least an hour. VAS pain score progressed to 0 on the 0-10 scale. The diastasis was measured at discharge to be 2 cm at the umbilicus, 1 cm above the umbilicus, and 0 cm below the umbilicus. This case report is first an excellent example of a detailed case example. Second, while the separation dramatically improved, most importantly, the patient’s function improved and her goals were met. This case is a wonderful example of how sharing details of a patient’s rehabilitation efforts can be useful for other rehabilitation therapists to consider when developing a plan of care.

If you are interested in discussing more about postpartum care, check out the first in our peripartum series, “Care of the Pregnant Patient” taking place next in Boston in May with Institute co-founder Holly Herman.

This post was written by Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCIA-PMB, who teaches the course Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain: Musculoskeletal Factors in Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. You can catch Elizabeth teaching this course in April in Milwaukee.

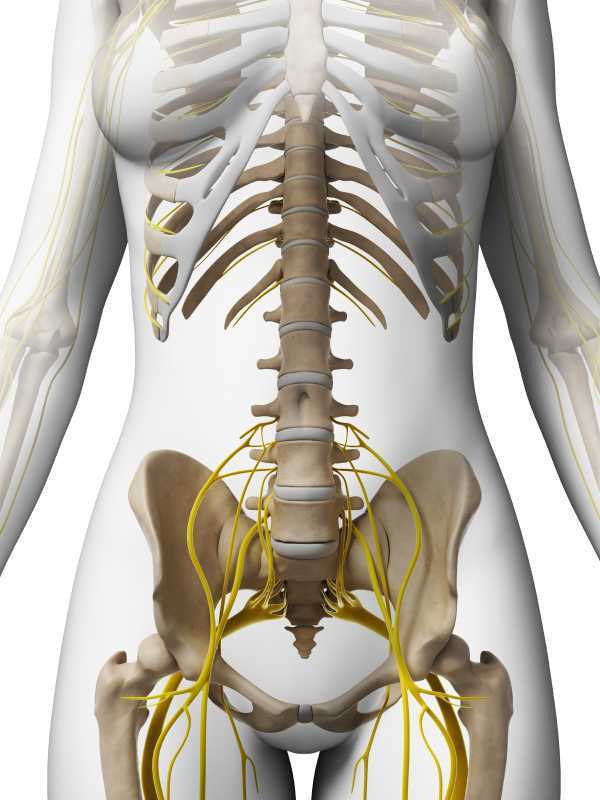

Chronic pelvic pain has multifactorial etiology, which may include urogynecologic, colorectal, gastrointestinal, sexual, neuropsychiatric, neurological and musculoskeletal disorders. (Biasi et al 2014) Herman and Wallace faculty member, Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCB-PMD has developed an evidence based systematic screen for pelvic pain that she presents in her course “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain”. One possible origin of pelvic pain as well as chronic psoas pain and hypertonus may arise from genitofemoral, ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric neuralgia, the screening of which is addressed in the “Finding the Driver” extrapelvic exam.

The iliohypogastric nerve arises from the anterior ramus of the L1 spinal nerve and is contributed to by the subcostal nerve arising from T12. This sensory nerve travels laterally through the psoas major and quadratus lumborum deep to the kidneys, piercing the transverse abdominis and dividing into the lateral and anterior cutaneous branches between the TVA and internal oblique. The anterior cutaneous branch provides suprapubic sensation and the lateral cutaneous branch provides sensation to the superiolateral gluteal area, lateral to the area innervated by the superior cluneal nerve. (10)

The ilioinguinal nerve arises from the L1 spinal levels, passes through the psoas major inferior to the iliohypogastric nerve, across the quadratus lumborum and iliacus and lastly through the transversus abdominis along with the iliohypogastric nerve between the transverse abdominis and the internal oblique muscle. (7) The ilioinguinal nerve supplies the skin of the medial thigh, upper part of the scrotum/labia as well as penile root (5).

The genitofemoral nerve arises from the L1 and L2 spinal levels and splits into the genital and femoral branches after passing through the psoas muscle. (1). The genital branch (motor and sensory) passes through the inguinal canal and innervates the upper area of the scrotum of men. In women it runs alongside the round ligament and innervates the area of the skin of the mons pubis and labia majora. The motor function of the genital branch is associated with the cremasteric reflex. The femoral (sensory) branch runs alongside the external iliac artery, through the inguinal canal and innervates the skin of the upper anterior thigh. (8)

Differential diagnosis of entrapment of one of the three nerves can be challenging due to their overlapping sensory innervations and anatomic variability. Rab et al found up to 4 different patterns of anatomical variability in these nerve pathways. (9)

Transient or lasting genitofemoral, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgia results from compression or irritation of these nerves anywhere along their pathway: from their spinal origin to distal pathways. Cesmebasi at al report that “neuropathy can result in paresthesias, burning pain, and hypoalgesia associated with the nerve distributions. “ (11) These entrapments may be associated with surgery, T12-L2 segmental dysfunction or HNP, constipation and is commonly observed clinically alongside psoas overactivity and pain. Lichtenstein found that up groin pain after hernia surgery ranged from 6-29% with Bischoff et al (2012) (6) denoting the post-operative neuralgia ranging from 5-10%.

Differential diagnosis of nerve entrapments are key skills in the screening of musculoskeletal contributing factors to pelvic pain and physical therapists are uniquely skilled to put all of the puzzle pieces together in these complex clients. Finding the Driver is being offered twice in 2015: April 23-25, 2015 at Marquette University and again in the fall. Check Herman & Wallace's webite for further details.

http://www.gotpaindocs.com/gentfmrl_nurlga.htm

Tubbs et al.Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. March 2005 / Vol. 2 / No. 3 / Pages 335-338. Anatomical landmarks for the lumbar plexus on the posterior abdominal wall. http://thejns.org/doi/abs/10.3171/spi.2005.2.3.0335

Phillips EH. Surgical Endoscopy. January 1995, Volume 9, Issue 1, pp 16-21. Incidence of complications following laparoscopic hernioplasty

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00268-012-1657-2

Tsu W et al. World Journal of Surgery. October 2012, Volume 36, Issue 10, pp 2311-2319. Preservation Versus Division of Ilioinguinal Nerve on Open Mesh Repair of Inguinal Hernia: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Bischoff JM. Hernia. October 2012, Volume 16, Issue 5, pp 573-577. Does nerve identification during open inguinal herniorrhaphy reduce the risk of nerve damage and persistent pain?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilioinguinal_nerve

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genitofemoral_nerve

Rab M, Ebmer And J, Dellon AL.. Anatomic variability of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve: implications for the treatment of groin pain.

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery [2001, 108(6):1618-1623].

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cutaneous_innervation_of_the_lower_limbs

Cesmebasi et al (2014) Genitofemoral neuralgia: A review. Clinical Anatomy. Volume 28, Issue 1, pages 128–135, January 2015. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ca.22481/abstract

This post was written by Megan Pribyl MSPT, who teaches the course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist. You can catch Megan teaching this course in June in Seattle.

Convalescence and mitohormesis…really big words that in a scientific way suggest “BALANCE”. In our modern world, there are many factors that influence the pervasive trend of being “on” or in perpetual “go mode”. We see the effects of this in clinical practice every day. The sympathetic system is in overdrive and the parasympathetic system is in a state of neglect and disrepair. And so we reflect on that word “balance” through the concepts of convalescence and mitohormesis.

Convalescence and mitohormesis…really big words that in a scientific way suggest “BALANCE”. In our modern world, there are many factors that influence the pervasive trend of being “on” or in perpetual “go mode”. We see the effects of this in clinical practice every day. The sympathetic system is in overdrive and the parasympathetic system is in a state of neglect and disrepair. And so we reflect on that word “balance” through the concepts of convalescence and mitohormesis.

“In the past, it was taken for granted that any illness would require a decent period of recovery after it had passed, a period of recuperation, of convalescence, without which recurrence was possible or likely.

Convalescence fell out of favor as powerful modern drugs emerged. It appeared that [antibiotics] and the steroid anti-inflammatories produced so dramatic a resolution of the old killer diseases… that all the time spent convalescing was no longer necessary.” (Bone, 2013)

How many of us take the time to convalesce after even a minor cold or flu? “Convalescence needs time, one of the hardest commodities now to find.” (Bone, 2013) We live in a culture where getting well FAST typically takes priority over getting well WELL.

On the flip-side of convalescence lies mitohormesis, or stress-response hormesis. Simply put, hormesis describes the beneficial effects of a treatment (or stressor) that at a higher intensity is harmful. Without mitohormesis, the driving, adaptive forces of life might lie dormant or find dysfuction. In a recent article (Ristow, 2014) mitohormesis is discussed: “Increasing evidence indicates that reactive oxygen species (ROS) do not only cause oxidative stress, but rather may function as signaling molecules that promote health by preventing or delaying a number of chronic diseases, and ultimately extend lifespan. While high levels of ROS are generally accepted to cause cellular damage and to promote aging, low levels of these may rather improve systemic defense mechanisms by inducing an adaptive response.”

Relevant to nutritional trends, Tapia (2006) suggests this perspective: “it may be necessary…to engender a more sanguine perspective on organelle level physiology, as… such entities have an evolutionarily orchestrated capacity to self-regulate that may be pathologically disturbed by overzealous use of antioxidants, particularly in the healthy.” Think of mitohormesis as the cellular-level forces that spur change. Motivation….drive….exhilaration. These life-sprurring stressors include physical activity and glucose restriction among other interventions.

The natural world is full of contrasts; day and night, winter and summer, land and sea, sun and rain. These contrasts are not only essential in creating rhythm to our existence, but necessary as driving forces of life. But what happens when there is not a balance of activity and rest? What happens when our energy systems go haywire? What nutritional factors play a role in whether a client of yours will have a healing and helpful course of therapy or may struggle with the healing process? How might we frame our understanding of the importance of balance through the lens of nourishment?

March is “National Nutrition Month”! It’s a perfect time to register for our brand new continuing education course Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist to learn more about how nutrition impacts our clinical practice. To register for the course taking place in June in Seattle, click here.

References

Bone, K. Mills, S. (2013) Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy; Modern Herbal Medicine. Second Edition. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

Gems, D., & Partridge, L. (2008). Stress-response hormesis and aging: "that which does not kill us makes us stronger". Cell Metab, 7(3), 200-203. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.001

Ristow, M., & Schmeisser, K. (2014). Mitohormesis: Promoting Health and Lifespan by Increased Levels of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Dose Response, 12(2), 288-341. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.13-035.Ristow

Tapia, P. C. (2006). Sublethal mitochondrial stress with an attendant stoichiometric augmentation of reactive oxygen species may precipitate many of the beneficial alterations in cellular physiology produced by caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, exercise and dietary phytonutrients: "Mitohormesis" for health and vitality. Med Hypotheses, 66(4), 832-843. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.09.009

Sexual dysfunction is a common negative consequence of Multiple Sclerosis, and may be influenced by neurologic and physical changes, or by psychological changes associated with the disease progression. Because pelvic floor muscle health can contribute to sexual health, the relationship between the two has been the subject of research studies for patients with and without neurologic disease. Researchers in Brazil assessed the effects of treating sexual dysfunction with pelvic floor muscle training with or without electrical stimulation in women diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS.) Thirty women were allocated randomly into 3 treatment groups. All participants were evaluated before and after treatment for pelvic floor muscle (PFM) function, PFM tone, score on the PERFECT scheme, flexibility of the vaginal opening, ability to relax the PFM’s, and with the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI). Rehabilitation interventions included pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) using surface electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback, neuromuscular electrostimulation (NMES), sham NMES, or transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS). The treatments offered to each group are shown below.

| Intervention

|

sEMG biofeedback PFMT: Use of intravaginal sensor and 30 slow, maximal-effort contractions followed by 3 minutes of fast, maximal-effort contractions in supine.

|

Sham NMES: sacral surface electrodes with pulse width of 50 ms at 2 Hz, on/off 2/60 seconds for 30 minutes

|

Intravaginal NMES: 200 ms at 10 Hz for 30 minutes using vaginal sensor.

|

TTNS: surface electrodes in the left lower leg with pulse width at 200 ms at 10 Hz for 30 minutes.

|

| Group 1, n = 6 | X | X | ||

| Group 2, n = 7 | X | X | ||

| Group 3, n = 7 | X | X |

The following factors made up some of the inclusion criteria for the study: age at least 18 years, diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS, 4 month history of stable symptoms, currently participating in a sexually active relationship, and able to contract the pelvic floor muscles. Participants were excluded if they had delivered within the prior 6 months, had pelvic organ prolapse (POP) greater than stage I on the POP-Q, were perimenopausal or menopausal. Neurologic function symptoms were also monitored so that subjects could be evaluated for any potential flare-up. Home program instruction in PFMT included 30 slow and 30 fast PFM contractions to be completed in varied postures 3x/day.

Results included that all groups improved via the PERFECT scheme evaluation. Other specific indicators of improvement were noted for each group, and the use of the FSFI provided measures of sexual function. The authors conclude that pelvic floor muscle training (with or without electrostimulation) can produce positive changes in sexual arousal, vaginal lubrication, sexual satisfaction and sexual lives. The use of PFMT with intravaginal NMES "…appears to be a better treatment option than PFMT alone or in combination with PTNS in the management of the orgasm, desire and pain domains of [the FSFI]." You can find the abstract of the article by clicking here.

Patients who are managing disease symptoms of MS have many aspects of the disease that can interfere with sexual health, such as energy levels, neurologic impairment, and pain. Use of modalities such as biofeedback and/or electrotherapy may be useful adjuncts in the care of women who have MS. Prior research has identified the benefits of electrotherapy for urinary dysfunction in patients who have MS. The described research allows us to consider inclusion of these tools along with pelvic floor muscle training when working with women who experience sexual dysfunction as a part of MS.

In our weekly feature section, Pelvic Rehab Report is proud to present this interview with Herman & Wallace instructor Michelle Lyons, PT, MISCP

How did you get started in pelvic rehab?

Like a lot of therapists whom I talk to when I travel and teach, it was after the birth of my daughter, when I realized what an under-served population postpartum women are! After childbirth, the focus almost entirely shifts to the baby, and poor old Mum is left, by and large, to fend for herself. Now, more than ever, when we are looking at shorter hospital stays and the lack of maternity leave, we as pelvic therapists need to grow awareness of the needs of women throughout the life cycle and what we have to offer. Pelvic rehab is a high touch, low risk, cost effective and highly effective (yet under used) treatment option. I am passionate about spreading the Pelvic Rehab Gospel!

Who or what inspired you?

Holly Herman. The woman is a pelvic legend. If you get the chance to take one of her course, do it. An amazing breadth, width and depth of expertise and experience.

What do you find more rewarding about teaching?

Confession: I am a pelvic nerd. I just love talking about the fascinating interplay of anatomy, physiology, psychology, form and function. I am (almost) never happier than when I get to spend a weekend with a group of therapists exploring diagnoses, assessments, interventions and outcomes with a like minded group of pelvic health professionals. Whenever I teach, I always learn something too – I really like the classes I teach to be conversational and we tend to have some interesting sidebars and tangents! But I think that just adds to the learning experience – we have all had different pathways educationally, personally and professionally, and I think that looking at different perspectives and approaches can only be a good thing, especially for the patients we treat.

How did you get started teaching pelvic rehab?

My background was in sports medicine and MSK dysfunction. I come into the wonderful world of pelvic health about 15 years ago. Now I look on that background as being incredibly important – I think in order to be a great pelvic therapist, you really need a solid orthopedic expertise. You can’t treat the pelvic floor without looking at the pelvic girdle (and spine and hips and feet and …..!)

What trends/changes are you finding in the field of pelvic rehab?

I think we are learning more and more about Pain Science – sometimes on a daily basis. I think one of our primary role as pelvic therapists can be as educator – I often say to classes that most people know more about their phones than they do about their own bodies! So having anatomical models, books and learning aids can be a great way to empower our patients. I always emphasize including biopsychosocial approaches in working with patients, talking about issues like central sensitisation, the effects of chronic pain and worry on the brain etc BUT I do think we have to be careful, too, that we don’t ignore the biomedical. Sometimes I worry that the pendulum is swinging too far – we have to be sure that we are addressing the physical problems as well!

The other big trend I see is engagement on social media! Just over a year ago, after I taught a course in the UK, I set up a Facebook group with my friend & colleague, Gerard Greene, called Women’s Health Physiotherapy. We now have over 2300 members from all over the world and it is so heartening to see international colleagues from the US, the UK, Australia, the Middle East and Ireland talking, sharing ideas, questions, resources and clinical reasoning. So reassuring to know that others have dealt with the same problems we may be facing in our daily patient caseloads! The Facebook group has been a great success and in fact we submitted a poster based on the group looking at how SoMe can benefit physiotherapists internationally and it has been accepted for presentation at WCPT in Singapore in May.

If you could get a message to all therapists about pelvic rehab, what would it be?

You have such an amazing skillset – you have the power to effect HUGE change in your patients’ lives. The CSP (the governing body for Physiotherapists in the UK) acknowledges that pelvic health is one of the few growth areas within our profession. I think as pelvic therapists, we have the ability to integrate gynaecological, obstetric, orthopaedic, hormonal, oncological and biopsychosocial systems. We are skilled interviewers, skilled manual therapists and skilled exercise/lifestyle precribers. We have the ability to take our patients from being passive recipients to active participants in their own healthcare. It is the best job in the world!

If you could make a significant change to the field of pelvic rehab or the field of PT, what would it be?

I would love to see our role more widely understood and acknowledged. Most of our medical colleagues don’t know what we do! The other big change I would love to see in the U.S. is national registration – I hear from so many therapists how restrictive individual state licensure is and how it can hold them back from job opportunities. I do understand that this is an issue that is hopefully on the horizon, and I think that will be a huge boost to our profession!

What have you learned over the years that has been most valuable to you? Never stop learning! There are always more books to buy, articles to read and courses to attend, but it is just as important to take time to assimilate new knowledge and always ask yourself – ‘Does this change how I would practise? How? Why?' Got to love that clinical reasoning skill set!!

What is your favorite topic about which you teach?

So….this is a tricky one! I teach the Pelvic Floor series and the Pregnancy series. I have developed a number of specialty topics for Herman & Wallace over the years – The Athlete & the Pelvic Floor, Menopause – a rehab approach, Special Topics – Endometriosis, Infertility & Hysterectomy and Oncology & the Male Pelvic Floor and Oncology & the Female Pelvic Floor. To pick just one is impossible! I truly love teaching them all, but if I had to narrow it down I would have to have joint winners. PF1 because I really see this course as the ‘gateway drug’ to a career in pelvic health – I just love to watch as participants move from that first scary lab session (!) to the end of Day 3 and feeling of ‘Yes! I get this! I love pelvic rehab!’. The other joint winner would have to be Oncology & the Female Pelvic Floor – we have so much to offer the survivors of gynaecological cancers. However, unlike our well publicized and relatively well researched role in prostate cancer rehab, gynae cancer survivors are often left to deal with problems encompassing orthopedic, soft tissue, lymphatic, sexual and continence function issues. We have work to do in raising our profile in cancer survivor-ship programs for these women. So, talking about the effects of cancer and cancer treatment on life with and after cancer is an issue I feel very strongly about.

In order to refer patients to needed care, it is vital that health care providers understand the roles that each provider plays. Within pelvic rehabilitation, this issue presents barriers and opportunities, as many providers do not know about pelvic rehabilitation, and about the wide scope of care that we can provide towards bowel, bladder, sexual dysfunction, and pelvic pain in men, women, and children. An article written by a physiotherapist and published in the British Journal of Midwifery highlights the issues such barriers can cause. Utilizing a focus group of seven 3rd year midwifery students, a researchers asked questions about student midwives' perceptions of the physiotherapist's role in obstetrics. Five distinct themes were proposed as a result of the focus group interviews:

1. Role recognition: in order to enable services for patients, understanding other professional roles is valuable.

2. Lack of knowledge: participants expressed a lack of knowledge about the physiotherapy role, and the students wondered if they should be seeking out that knowledge, or if the physiotherapists should be educating the midwives about their role. Prior inter professional education opportunities, which provides the students with potential for understanding other professions, were not viewed as positive by the students.

3. Perceived views existed: Although participants did not have a clear view of what a physiotherapist's role is in obstetrics, they had developed ideas (accurate or not) about the role.

4. Utilization of physiotherapy: Numerous barriers to utilization of physiotherapy in obstetrics rehabilitation were identified, and variations in referrals and utilization of PT were noted.

5. Benefits of physiotherapy: Participants' lack of knowledge, lack of feedback from patients, and issues such as waiting periods prior to getting care limited the stated benefits of physiotherapy care in obstetrics.

In order to avoid working independently of each other, physical therapists and midwives, along with other care providers for women, must understand the complementary roles we play. One of the best ways that we can create a shared understanding is through spending time in each other's educational or clinical environments. Each of us can take responsibility for providing some level of education towards teaching other providers what we do, what we know, and how we can collaborate. One of the ways that the Institute attempts to make this task easier is to provide you with presentations that are already created for this purpose. Our "What is Pelvic Rehab?" powerpoint presentation allows you to edit the slides created for referring providers. Within the presentation, basic information about pelvic therapy and specific research about pelvic rehabilitation for various conditions is combined. To check out the "What is Pelvic Rehab?" presentation and other patient and provider education materials, head to the Products and Resources page and see what information may help you (and your patients) share information about the role of the pelvic rehabilitation provider in collaboration with other health professionals.

Researchers using a community-based sample in the upper Midwest cities of Minneapolis/St. Paul surveyed 138 women between the ages of 18-49 with diagnosed vulvodynia. Vulvodynia was classified as primary (pain started with first tampon use or sexual penetration) or secondary pain started following a period of intercourse that was not painful. The authors aimed to determine the rates of remission of vulvar pain versus pain-free time periods. Remission was defined in this study as having at least one period of time that was pain-free for at least 3 months. Generalized vulvodynia categorization was made after clinical exam and was determined by the subject having pain at each point on the perineal “clock” with cotton swab provocation.

The authors reported that women diagnosed with primary vulvodynia were 43% less likely to report vulvar pain remission that women with a diagnosis of secondary vulvodynia. They also found that obesity and having generalized versus localized vestibulodynia was associated with reduced rates of remission. The theory was discussed that women who have different types of vulvodynia may have varied underlying mechanisms of pain that lead to differences in symptoms. Specifically, the paper reports on recent brain imaging work that suggests women who have primary vulvodynia demonstrate more characteristics of central pain processing.

In relation to health behaviors (such as seeking pain therapy), the authors state that the data may not be sufficiently powered to determine the influence of therapy on remission. They do agree that “…understanding of both spontaneous remission and improvement owing to therapy will ultimately provide guidance in developing more effective interventions.” Because a significant portion of women do not seek care for vulvar pain (for unknown reasons), a bias is created in the research through the lack of representation of those women who are not being studied through healthcare access.

The research concludes with a few familiar themes including the need for more research studying the clinical courses of primary versus secondary vulvodynia. We are also left with questions about which women seek care and why, how their clinical outcomes and remission history may differ based on intervention and other intrinsic variables such as body mass index, and how central pain processing affects pain duration and remission. If you are interested in learning more about vulvodynia, come to one of our newer courses offered by faculty member Dee Hartmann, Assessing and Treating Women with Vulvodynia. Two entire days are spent discussing vulvodynia theory and clinical skills for helping women optimize their health and function. You still have a few weeks to sign up for this course that takes place next in April in Minneapolis!

In our weekly feature section, Pelvic Rehab Report is proud to present this interview with Herman & Wallace instructor Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC

How did you get started in pelvic rehab?

A supervisor of mine suggested that I go to a course and develop a pelvic floor program. I thought she was nuts. As a late twenty-something, I wanted to work with athletes. Finally she convinced me to go. Imagine my surprise when I felt like a duck in the water in the Pelvic Floor Level 1 class.

Who or what inspired you?

Truly I was smitten by Holly Herman at PF1. Her unique teaching style combining her incredible knowledge and fascinating stories with compassion and clarity is something to behold. Later I met Kathe at PF2A and was so inspired by both of these amazing women.

What have you found most rewarding in treating this patient population?

It is such an honor and a privilege to do what we do. At times we share a facet of our patients lives that even their spouses or best friends don't know about. It is not rare for someone to tell me, "I've never told anyone that before." Being trusted to share in these private experiences with others is a blessing to me.

What do you find more rewarding about teaching?

That's easy! I love the "ah-ha" moment when the light comes on in someone's eyes. When they "get it", whether it's finding the ATLA for the first time or understand another treatment direction for a complex patient, this is the moment that I love. I also treasure being around other people who love to do what I love to do!

How did you get started teaching pelvic rehab?

My hospital hosted the PF series years ago and I got to TA. I invited Holly and Kathe out to dinner and basically begged them to think of me if they ever had a teaching position open. Luckily the company was growing and I was shocked to have an opportunity to teach PF2B within a year. I was thinking maybe in 5 years, but I jumped at the chance.

What was it like the first time you taught a course to a group of therapists?

I was SO nervous. I studied like crazy for 6 months! I thought I did a horrible job until I read the reviews at the end of the course and realized I did okay.

What trends/changes are you finding in the field of pelvic rehab?

The amount of knowledge and research in our field is exploding. There are amazing blogs and recourses online for both patients and therapists to get information. Patients are coming in much more educated. Doctors seem to be getting the message that pelvic floor PT is a good first line option for their patients.

If you could get a message to all therapists about pelvic rehab, what would it be?

Every therapist should know a pelvic floor therapist and know when a consult would be appropriate. All therapists should try to feel more comfortable asking appropriate patients about elimination and sex.

If you could make a significant change to the field of pelvic rehab or the field of PT, what would it be?

I would love to see more of a team approach between physicians, PTs, therapists, pain clinics, nutritionalist, etc. especially in treating complex pelvic pain.

What have you learned over the years that has been most valuable to you?

Oh so much. Listen to your patient and hear what he or she or he is telling you. Don't feel like you have to have everything figured out on the initial evaluation. Treat what you find and continue to evaluate and listen.

What is your favorite topic about which you teach?

I think it changes each time, but right now I am really interested in relaxation techniques and down training especially as we understand more about the brain's involvement in pain responses.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./