Are you eligible to become pelvic rehab certified?

The rigorous and psychometrically validated Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification (PRPC) will be offered for the third examination this year. You still have time to join the nearly eighty practitioners who have earn their letters! (Keep in mind that, different from a "certificate", this certification allows you to use the designation "PRPC" after your name, helping to distinguish you as an expert in pelvic rehabilitation. In case you are uncertain if you are a candidate to sit for the PRPC examination, check out some commonly-asked questions below.

Types of practitioners: Do I have to be a physical therapist?

You do not need to be a physical therapist in order to apply for the PRPC exam. What is required is that you have a license to practice the skills utilized in pelvic rehabilitation. Such a license may include physician (MD, DO, ND), registered nurse (RN), occupational therapist (OT), advanced registered nurse practitioner (ARNP), or physician assistant (PA-C). Any other provider can apply and will be examined on a case-by-case basis.

Coursework: Do I have to take certain Herman & Wallace courses?

There are no prerequisite courses that you need to take before registering for the examination. Most providers, in order to work with patients who have pelvic dysfunction, will take a variety of continuing education courses to round out their knowledge and skills for bowel, bladder, sexual and pelvic pain dysfunctions. Various providers will also have had differing training within their respective professional education and clinic experience.

Experience: How much pelvic rehabilitation experience do I need?

You must have 2000 hours of experience in pelvic rehabilitation within the past 8 years, with 500 of the hours occurring within the last 2 years.

Details: Where can I find more information?

All the details can be found on our website at the following link: https://hermanwallace.com/pelvic-rehabilitation-practitioner-certification. You can find sample questions, pricing of the exam and application, and even find some study resources!

Deadlines: By when do I need to register?

The registration cut-off date for the next exam in May of 2015 is April 1st. The sooner you get your application approved, the faster you can be connected to like-minded practitioners who want to study with you for the exam! This is the only certification that is specific to pelvic rehabilitation for men and women across the lifespan. Most who have taken an exam will tell you that while the exam is not "fun", the studying really steps up your clinical practice as you have a chance to broaden and deepen your knowledge and refine your skills. Good luck!

As a physical therapist I am continually amazed at the myriad of ways the parts of our bodies are connected (and even more so by our brain/body connections, but that is another blog post.) Take one of my favorite muscles for example, the obturator internus. This amazing muscle is known for its relationship to the hip as one of the external rotators, and it’s anatomy is impressive! What other muscle sharply turns ninety degrees from its attachment to its origin? The obturator internus traverses the inside of the pelvis and attaches mid-belly to an important tendon, the Arcuate Tendon Levator Ani (ATLA) , which becomes the means by which the obturator connects to the pelvic floor. (I love to show patients how their hip literally connects to their pelvis!) The ATLA connects with the Arcuate Tendon Fascia Pelvis which connects to the fascia supporting the bladder and urethra.

We know that in our patient who have pelvic pain too much tension or trigger points in the obturator internus can create symptoms of urinary urgency or frequency, pain in the bladder, vagina, rectum, abdomen, pelvic floor and hip. But what happens when the obturator internus is uptrained to treat women with stress urinary incontinence (SUI)? An article in the May/August 2014 Journal of Women’s Health looked at the role of strengthening the obturator internus and the adductors and compared the effects to working the pelvic floor for the treatment of women with SUI. The results were quite interesting.

This research was a pilot study comparing two randomly assigned groups of community dwelling women with SUI. A group of 12 completed resisted hip rotation (RHR) and a group of 15 completed pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). Each group exercised at home for six weeks with a weekly recheck. Outcome measures included subjective reports of improvement, leak frequency, and scores from the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) and the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI). The exercise routines were supposed to take about 5 minutes and be performed twice a day. Subjects were instructed to sit with good posture and with their feet on the floor. The pelvic floor muscle group performed 5-second holds for 20 reps followed by 20 quick contractions. The RHR group exercised by 1) rotating internally and externally with diaphragmatic breathing for 10 breaths , 2) 10 repetitions of resisted hip external rotation with a green band and 5 second work/rest cycle and 3) 10 repetitions of hip internal rotation/adduction against a 9 inch ball with the same 5 second squeeze and rest cycles.

The results of the study showed that BOTH groups had significant and equal improvement in outcome measures by the end of the six weeks, but that the RHR group showed improvements sooner than the PFMT group. The authors discuss the limitations of their study: small sample size, large ranges of participant ages, patients were not medically examined, outcome measures were subjective, and the pelvic floor group only received verbal instruction. This study was thought provoking to me for several reasons. First, it gives me a great platform to talk with my non-pelvic health colleagues about treating pelvic floor weakness dysfunctions with indirect pelvic floor treatment. Virtually any patient could sit and roll their legs in and out against resistance! This exercise could be easily incorporated into a routine for people with bladder leakage or at risk for bladder leakage. Secondly, we often see patients with non-functioning pelvic floor muscles. My typical protocol before discussing the treatment option of electrical stimulation is to uptrain (increase muscle activity) with hip rotation, adduction and transverse abdominus muscle exercises. I have often found that I don’t need to address the pelvic floor directly when the accessory muscles are appropriately engaged. This study points out the importance of muscles outside of the pelvic floor in providing support for continence.

Thirdly, can we extrapolate the benefit of resisted hip exercise into more functional or more challenging exercises for our high level athletes or moms who want to jump on the treadmill with their kids? Would this approach be helpful? I know many of us are already doing this. Could this idea be a future research project? Lastly, John Delancey published in an anatomy study of cadavers that the muscle fibers around the striated urethral sphincter decrease in density and number at a rate of 2% a year after the age of 35!!! The process might go a little faster with higher parity and slightly slower in women who have never been pregnant. Could this mean that our reliance on our accessory muscles increases with age? Perhaps using both pelvic floor and resisted hip strengthening will lead to improved outcomes in older women.

One reason I love to read research is because it gets my brain thinking not only about how interconnected our bodies are, but I also ask myself what else I want to know about this subject and how can this information be used. We may not have the research-validated information we want yet, but applying critical reasoning to our clinical practice is the first step in further understanding.

You can join faculty member Jennafer Vande Vegte at an upcoming intermediate PF2B course. Keep in mind that these pelvic floor continuing education courses sell-out months in advance! With courses on both coasts and in the middle of the US, hopefully you can find a location that works best for you!

This post was written by H&W instructor Ginger Garner. Ginger will be presenting her Hip Labrum Injuries course in Houston in March!

1. Early Intervention Is Key

Acetabular labral tears are reported to be a major cause of hip dysfunction in young patients and a primary precursor to hip osteoarthritis. New technology is helping with improved identification of tears, however the time of injury to diagnosis is still on average 2.5 years, making long-term prognosis for hip preservation poor.

Because of the lengthy delay many patients are still experiencing, the importance of early intervention cannot be overemphasized.

2. Getting the Best Outcomes: Patient Stories & Details Matter

Patient stories, the subjective reports of the individual, are incredibly important in aiding diagnosis of a hip labral tear. Knowing the morphological classification and common areas for tears in the hip labrum is also important, especially when it comes to identifying and managing adverse biomechanical stressors, such as anterior joint loading in the hip. Quite often in conservative treatment of hip labral injury, it is more important to change or retrain nonoptimal movement strategies rather than to issue exercise, strengthen, or elongate tissues.

Up to 55% of active people with mechanical hip pain are typically confirmed as having acetabular hip labral (ALT) tears, which is affirmed across several research studies. And since 2003, the most commonly cited area of hip pain for labral tears is anterior, followed by lateral, then posterior.

3. Study History to Affect the Future

Suzuki, in 1986, described the acetabular labral tear arthroscopically for the first time, while Altenburg, in 1977, documented the first report of “nontraumatic tearing of the acetabular labrum,” according to Groh and Herrara 2009, Schmerl 2005, and Altenburg 1977. And yet, it is possible for an ALT to go undiagnosed and pain-free, since up to 96% of cadaver hips with a mean age of 78 years old are found to have ALT in the anterosuperior quadrant.

A paucity of studies existed on hip disorders from 1977-2011, having located approximately 70 during early research on the topic. Plante et al (2011) and Margo et al (2003) confirm these findings, stating “there is no clear consensus on diagnosis or terminology” (concerning ALT).However, the increasing interest in ALT is a welcome phenomenon, and in a a second literature review from 2011 to present I located and reviewed over 100 new studies relating to ALT and its often comorbid sister condition, femoracetabular impingement (FAI).

4. What Matters Most in Symptomology?

There are some moderately reliable tests that have undergone scrutiny as to their sensitivity (SN) and specificity (SP) for clinical utility and validity; however, that is a discussion for another post. For now, what matters most in diagnosing ALT?

The short answer is the patient story. Listen to a patient’s onset of symptoms and mechanism of injury (if there is one, oftentimes there isn’t unless the mechanism is pregnancy or postpartum-related. For more information, read my post on postpartum hip labral injury risk. Listen carefully the most typical (and reliable) symptomology for a suspected ALT. Those symptoms would include:

- Pain in the groin (reported 95-100% SN)

- Mechanical symptoms, which can include sharp pain, clicking, locking or catching, or giving way (reported 85-100% SP, SN, respectively)

- Minor hip ROM (range of motion) limitations (same SP and SN as above)

Could There Be a Future Hip Labral Injury (HLI) Scale?

The last symptom that can be incredibly telling (read: reveal the degree of functional impairment and degree of ALT), is night pain. Similar to the RTC impingement degrees of impairment (Stages l I, II, and III), ALT injury is similar. Once a patient’s sleep is interrupted, and is accompanied by any of the symptoms found above, the risk of their having an ALT or other intra-articular (internal) hip derangement is high. Night pain could then be characterized by the most impaired stage, Stage III, lending itself to the possibility of a future HLI Scale.

The findings reported in this post are supported by more than two dozen references, which are a part of the literature review included in the Hip Labral Injury and Differential Diagnosis course that Ginger authored and teaches for Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

To learn more about nonoperative and operative hip labral and FAI management, check out faculty member Ginger Garner's continuing education course on Extra-Articular Pelvic and Hip Labrum Injury: Differential Diagnosis and Integrative Management. The next opportunity to take the course is March of 2015 in Houston.

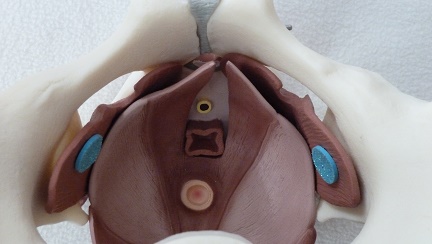

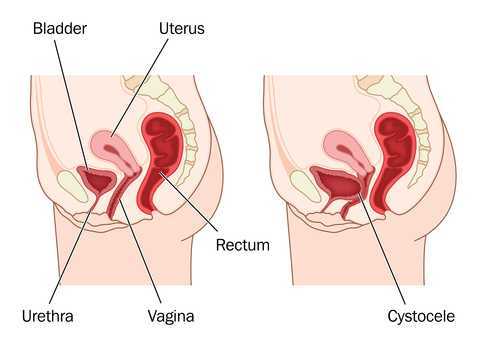

When examining a patient clinically for pelvic wall relaxation or pelvic organ prolapse, we know that verbal cues given, position of the patient, time of day, bladder fullness, and other variables can affect the outcome of the prolapse evaluation. What about the number of attempts at bearing down or straining during the examination? Is one attempt at bearing down enough to provide clear information about the level of descent or relaxation in the pelvic walls or organs? If research based on dynamic MRI's is any indication, the answer may be "no."

40 women with an anterior wall prolapse that extended at least 1 cm beyond the hymenal ring were evaluated with dynamic MRI scans. The subjects were instructed in and evaluated for their ability to properly bear down prior to the scans. Between the first, second, and third maximal efforts at bearing down, or Valsalva, bladder descent was measured during dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In 95% of the women, prolapse measurements were more significant by the third effort at bearing down. 40% of the women demonstrated more than a 2 centimeter increase in prolapse from the first to third attempt at Valsalva. In this research study the mean age of the subjects was about 60 years old, and 80% of the women were Caucasian. Childbirth history averaged 2 vaginal births and eight of the women had a prior hysterectomy.

While the authors discuss the value of using this diagnostic information to create improved dynamic MRI protocols, there may also be implications for the pelvic rehabilitation provider. When we are assessing for the integrity of the pelvic supporting structures, are we getting a reliable effort from the patient? Are we asking for more than one attempt at bearing down? In addition to considering relevant issues like the time of day or the position of the patient during an examination, we can also consider the number of times that the testing is completed. If we ask for only one attempt at bearing down, perhaps we are not being provided with the most accurate information. What we do with that information is the next important step in developing a plan of care or communicating with the referring provider. In the Pelvic Floor Level 1 (PF1) continuing education course, therapists learn how to assess for pelvic organ prolapse, and in the PF2B course therapists learn additional information about the fascial layers that, when not intact, can contribute to pelvic organ displacement. Providing interventions that address myofascial dysfunction and functional use patterns of the trunk and limbs can help a woman overcome symptoms of prolapse, and working together with medical providers to help women with prolapse can be very rewarding.

Authors Yadav, Narang, and Kumaran in a recent review on psychodermatology report that a significant portion of patients who seek care from a dermatologist has "…an underlying psychiatric or a psychological problem that either causes or exacerbates a skin complaint." The relationship between the mind and the skin may have their link in embryology, with brain and skin sharing development from the ectoderm's end plate, according to the linked article. Psychodermatologic disorders are categorized by Yadav and colleagues into psychophysiological disorders (skin disease is affected by the patient's psychological state), primary psychiatric disorders (skin complaints are secondary to a psychological pathology) or a disorder of dermatological beliefs (rare occurrence of incorrect belief that skin is infested.) For a clinical example of psychophysiologic skin issues, we can consider the affect that stress can have on creating skin disruptions from the herpes virus. Primary psychiatric disorders might include anxiety or depression, comorbidities from which many of our patients suffer.

In addition to pointing out the necessary medical management of any skin condition, the article notes that there are other recognized approaches that can assist a patient in healing well and in avoiding exacerbations. For example, biofeedback training is listed as a helpful modality for hyperhidrosis, Raynauds phenomenon, dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus, urticaria, and post herpetic neuralgia. Certainly many of our patients are dealing with these and other comorbidities, and many therapists are also aware of the value in teaching stress-management techniques such as breathing, using biofeedback, and avoiding catastrophizing. The article concludes the following: "Awareness and pertinent treatment of psychodermatological disorders among dermatologists will lead to a more holistic treatment approach and better prognosis in this unique group of patients."

In addition to being helpful for dermatologists, this information may serve pelvic rehabilitation providers and their patients. For example, if mast cells in the skin can be impacted by stress hormones, can this same stress affect through neuroendocrine pathways the skin of the genital area? Research in conditions of chronic pelvic pain have asked this question, in relation to mast cells and other mediators of potential pain sources, with inconclusive results. Regardless of the source of the pain, this article reminds us to look beyond the matter to the mind, and to be helpful to our patients in considering the effects of either. If a patient presents with a skin condition, can we direct him or her to a dermatologist or discuss the potential benefits of managing stress with specific strategies to minimize the impact of the skin issue? If you are interested in learning specific strategies in stress management, check out the Institute's continuing education courses on Meditation as well as on Mindfulness-Based Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain. We are still scheduling these courses this year- if your facility would like to host either (or both!) of these courses, please contact us at the Institute.

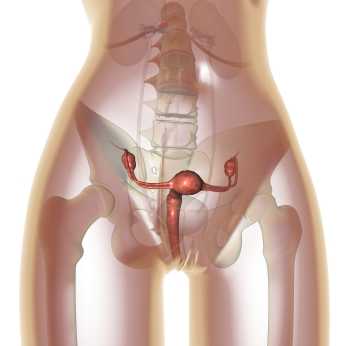

In women who have endometriosis, ablation procedures are commonly completed to destroy endometrial tissue lining the uterus. A goal of ablation is to disrupt severe bleeding that can lead to other conditions including anemia. Research published in last month's Obstetrics & Gynecology identified the risk factors for pain and subsequent hysterectomy following ablation procedures for endometriosis. Of 300 women, 270 completed follow-up, and the resultant data was reported:

- -23% developed new onset or worsening pain after the ablation

- -19% proceeded to hysterectomy

- -a history of dysmenorrhea increased the risk of developing pain by 74%

- -a history of tubal sterilization increased the risk of developing pain by > 50%

- -women of white race were 45% less likely to develop pain

- -a history of cesarean delivery more than doubled risk of hysterectomy

- -uterine abnormalities such as leiomyoma, adenomyosis, thickened endometrial strip, or polyps quadrupled the risk for hysterectomy

For the nearly 20% of these women who had a hysterectomy after ablation therapy, the most common indication for the hysterectomy was pain. Regarding the increased risk of pain after ablation in non-white women, the authors proposed the higher rates of leimyomatous uteri in African American women (largest population of non-white women in the study) as a source. Because pain is a potential complication of endometrial ablation, the authors of this article recommend that providers consider patient characteristics when educating patients about the potential benefits and risks of the procedure.

Although in pelvic rehabilitation we do not counsel for or against surgical procedures, knowledge of the potential risk factors for our patients who have had or who are having a uterine ablation can assist in our screening and interventions. If a patient asks our opinion about uterine ablation, pointing out research such as the linked article may help her discuss pros and cons with us and with her providers. The need for patients to understand the potential side effects of a uterine ablation and to actively manage her recovery may be important in avoiding hysterectomy, if that is the patient's goal. Endometriosis is one of the main topics in a new course offered by faculty member Michelle Lyons. The new continuing education course "Special Topics in Women's Health: Endometriosis, Infertility, and Hysterectomy" will be offered in March in San Diego and the Chicago area in May.

This post was written by H&W instructor Peter Philip, PT, ScD, COMT, PRPC, who authored and instructs the Sacroiliac Joint Evaluation and Treatment course. The next SI Joint course will be taking place this January in Seattle.

Patient one:

55 year old female with complaints of pelvic pain. States that her pain is noted along the deep inguinal region, involving her pubis and labia majora. States that intercourse is difficult, and that she is quite anxious to initiate or participate. She denies trauma, only that she’d been increasing her fitness activities as she’s going to Florida for a winter get-away. She denies changes in her bowel and bladder function, other than intermittent SUI with ‘heavy exercise’.

Clinical testing:

ALROM is negative. During forward flexion there was no reversal of the lordosis.

Segmental myotomal and dermatomal testing is unremarkable.

ASLR and PSLR are negative.

Gillet’s and forward flexion are apparently negative.

There are palpable “marbles” to palpation along bilateral SIJ, and the sacrum is ~40? of nutation.

FABER, FAIR and McCarthy tests are negative. Iliac compression is modestly provocative for patient’s symptoms, while the sacral thigh thrust was provocative for ipsilateral symptom provocation.

While in prone, the patient demonstrated a positive Dead Butt Syndrome bilaterally and there were significant restrictions to fascial rolling throughout the lumbosacral region.

The clinical question is: What to do next? What would you do?

I chose to provide a local traction to each SIJ, followed by a mobilization with movement directed at S3 to promote counter nutation. After treatment, the patient arose from the plinth and remarked that her pain was significantly reduced. On follow up, her pain was 10% that of her initial pain at evaluation.

My questions to you are:

1. What caused her “pelvic pain”?

2. Why did her pain subside? 3. Would you have done an internal evaluation?

These and other questions will be addressed at Sacroiliac Joint and Pelvic Ring Evaluation & Treatment in Seattle, Washington January 25th to the 26th.

Catastrophizing is a buzzword in relation to pain, but what does it really mean for our patients and for our plan of care? Catastrophizing, according to Iwaki and colleagues is a maladaptive response to pain, with research supporting the idea that level of catastrophizing behavior may predict a patient's level of function. A terrific blog post on the Psychology Today website by Alice Boyles, PhD, translates the term into everyday symptoms of this behavior. She describes catastrophizing as having 2 parts: predicting a negative outcome, and then concluding that if the negative outcome happens, this would be a catastrophe. Imagine our patients who develop a painful condition, and then jump into a "worst case scenario." A patient who develops pelvic pain may think "I will never get rid of this pain", and then perhaps, "I will never have a partner and a healthy sex life."

Several prior blog posts on the Herman & Wallace website have specifically addressed different conditions and the role of catastrophizing. Some of the posts include the following topics:

Catastrophizing in Male Chronic Pelvic Pain

Lumbopelvic Pain and Catastrophizing in Pregnancy

Psychological Factors in Female Pelvic Pain

The study by Iwaki and colleagues also reported on subdomains of catastrophization and reported that the trait of helplessness was predictive of pain intensity, pain interference and depression, and that magnification of symptoms was predictive of anxiety. Regardless of the extent to which catastrophization impacts healing, being able to reframe pain and healing for our patients becomes a necessity so that the patient can focus on the steps involved in healing. The Institute now offers several continuing education courses designed to teach the therapist skills to address catastrophization including Meditation for Patients and Providers, and Mindfulness-based Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain.

If pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is instructed as part of a general exercise class during pregnancy, can this (PFMT) prevent urinary incontinence? A recent post on our site described the systematic review by Bo and colleagues in which the researchers suggested that fitness instructors and coaches should be trained in effective pelvic floor muscle training approaches. A recent article describes such an approach in which a Physical Activity and Sports Sciences graduate instructed in a general exercise class for pregnant women and the class also included PFMT. Nulliparous women completed participation in a pregnancy exercise class (n=63) or a control group (n=89), and in the exercise group, pelvic floor muscle exercises were included. The classes took place 3x/week, for 55-60 minutes each session, for up to 22 weeks, and 8-12 women were in each group class.

Within each exercise class, a typical prenatal program was followed consisting of an 8 minute warm-up, 30 minutes of aerobic training including 10 minutes of strength training, 10 minutes of PFMT and a 7 minute cool-down period. A heart rate monitor and a Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale was used and the women were asked to exercise at a 12-14 on the Borg scale. For pelvic floor muscle training, women were instructed in the anatomy and function of the PFM and in the role of the PFM in urinary incontinence. Although the participants were not formally assessed for correct contractions, the women were instructed in methods of confirming a correct contraction at home such as stopping the flow of urine, self-palpation, or using a mirror to confirm contraction. The PFM exercises started with 1 set of 8 contractions, and the class included both long (6 seconds) and short (1 second) contractions. The participants worked up to a total of 100 exercise contractions that included a combination of short and long contractions, and they were also encouraged to complete the same number of exercises on days outside of class.

Women in the control group received "usual care" including care from a midwife and instruction in pelvic floor muscle health. The outcome tool completed by both groups included the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire- Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) which was completed prior to and directly following intervention. At the end of the intervention, a significant difference was observed in the women in the exercise group (EG), as 95% of the EG denied leakage, whereas 61% of the control group denied leakage. Of those reporting leakage in the exercise group, the amount of leakage reported was small, and in the control group, amount leaked ranged from small to large. The key points of interest in this study include that first, participation in an exercise group that includes pelvic floor muscle training can prevent urinary incontinence in pregnancy, Secondly, although pelvic muscle function assessment is optimal, participants who did not have PFM contraction confirmed still had positive outcome from the treatment. And because most studies of PFMT are conducted by a physical therapist, this study is unique in its design of having a Physical Activity and Sports Science graduate conduct the intervention.

To learn more about training the pelvic floor, find out which course in the Pelvic Floor Series is right for you. If you have not been trained yet in internal pelvic muscle assessment, the Pelvic Floor Level 1 (PF1) continuing education course is a great place to start. This course fills up many months ahead of time, so check the dates on our website for the best course for you!

One of the challenges in assessing pelvic muscle function in women who have pain is to avoid triggering pain with the assessment tool. This challenge was met by the use of external measuring of pelvic floor muscles using transperineal four-dimensional (4D) ultrasound in this study by Morin and colleagues. Women who were asymptomatic (n=51) and symptomatic (n=49) were assessed with 4D ultrasound in supine with pelvic floor muscles (PFM) at rest and at maximal contraction. The women who were symptomatic were diagnosed with provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) and all of the women in the study were nulliparous. The data collected using the 4D transperineal US included anorectal angle, levator plate angle, displacement of the bladder neck, and levator hiatus.

Results of the study indicated that women with provoked vestibulodynia had a significantly smaller hiatus, smaller anorectal angle, and at rest, a larger levator plate angle. These differences suggested an increase in pelvic floor muscle tone. Additionally, when the PFM were assessed at maximal contraction, subjects with PVD demonstrated smaller changes in levator hiatus narrowing were noted, with decreased displacement of the bladder neck and decreased changes in levator plate and anorectal angles. These changes are believed to demonstrate pelvic floor muscle weakness.

The authors describe the value of the assessment technique, 4D ultrasonography, as having terrific advantage over other research methods due to the lack of required insertion of the US. While pelvic rehabilitation providers may concur that increased pelvic floor muscle tone in association with pelvic muscle weakness is a common clinical finding, research that describes the phenomenon is needed and much appreciated. We continue to find answers in research such as this article that answers the fundamental question: do women who present with pelvic dysfunction demonstrate differences in pelvic muscle health than a pelvic-healthy population? If you would like to learn more about provoked vestibulodynia including evaluation and management, join faculty member Dee Hartmann at the Assessing and Treating Women with Vulvodynia continuing education course. We are currently confirming dates for this course, and if you would like to host the Vulvodynia course, contact us at the Institute!

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./