Depression and anxiety can limit ability to care for one’s self, limit ability to care for a new baby or developing fetus, and can cause mood swings, impaired concentration, and sleep disturbance. Disorders of depression and anxiety are common in the perinatal period (immediately before and after birth) with depression rates around 20% and perinatal anxiety present in about 10% of women. These mood disorders greatly diminish quality of life for mother and baby. Medication may be effective, however, side effects are often unknown, and potentially adverse for the perinatal patient. Many women worry that using medication to treat these disorders may harm the fetus, negatively affect mother child bonding, and poorly influence child development. As health care providers, being aware of alternative treatments for depression and anxiety is essential. Having alternative treatments can allow our patients to combat these common perinatal problems which will improve quality of life, improve bonding between baby and mother and improve the overall perinatal experience. In the general population, positive mental and physical health benefits have been continually demonstrated by yoga participants in current research. Can yoga be an effective, alternative treatment to help perinatal patients improve mental health and well-being?

A recent 2015 systematic literature review published in the Journal of Holistic Nursing reviewed 13 studies to examine existing empirical literature on yoga interventions and yoga’s effects on pregnant women’s health and well-being. The conclusion of the review found that yoga interventions were generally effective at reducing depression and anxiety in perinatal women and the decrease in depression and anxiety was noted regardless of the type of outcome measure used and results were optimized when the study was 7 weeks or longer. Other positive secondary findings noted with the regular yoga participation in the perinatal participants were: improvements in pain, anger, stress, gestational age at birth, birth weight, maternal-infant attachment, power, optimism, and well-being. What is yoga and what form of it may help battle perinatal depression and anxiety?

A recent 2015 systematic literature review published in the Journal of Holistic Nursing reviewed 13 studies to examine existing empirical literature on yoga interventions and yoga’s effects on pregnant women’s health and well-being. The conclusion of the review found that yoga interventions were generally effective at reducing depression and anxiety in perinatal women and the decrease in depression and anxiety was noted regardless of the type of outcome measure used and results were optimized when the study was 7 weeks or longer. Other positive secondary findings noted with the regular yoga participation in the perinatal participants were: improvements in pain, anger, stress, gestational age at birth, birth weight, maternal-infant attachment, power, optimism, and well-being. What is yoga and what form of it may help battle perinatal depression and anxiety?

Yoga by definition is a Hindu philosophy that teaches a person to experience inner peace by controlling the mind and body. Merriam-Webster defines yoga as a system of exercises for attaining bodily or mental control and well-being. All styles of yoga include some combination of physical poses, breathing techniques, and meditation-relaxation techniques. Hatha yoga is the most common form completed in the United States and consists modernly of various postures, breathing, and meditation. In the 13 reviewed studies, all interventions consisted of different forms of yoga and the overall conclusion of the systematic review was the decrease in depression and anxiety was significant no matter the form of yoga completed. Physical and emotional issues such as hormonal changes, sleep deprivation, inability to handle new tasks, self-worth, and body issues, during the perinatal period can contribute to increased anxiety and depression. As health care providers we need to have alternative treatments to help our perinatal patients’ battle depression and anxiety. Yoga is a promising alternative to medication to help decrease depression and anxiety. Additionally it may be helpful for management of pain, anger, stress, gestational age at birth, birth weight, maternal-infant attachment, power, optimism, and well-being.

Interested in learning more about how you can apply therapeutic yoga in your practice? Check out "Yoga as Medicine for Pregnancy this April in Washington, DC!

Sheffield, K. M., & Woods-Giscombé, C. L. (2015). Efficacy, Feasibility, and Acceptability of Perinatal Yoga on Women’s Mental Health and Well-Being A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 0898010115577976.

The following post comes to us in part from Ginger Garner, PT, ATC, PYT, who teaches three yoga courses for Herman & Wallace; Yoga for Pelvic Pain, Yoga as Medicine for Pregnancy, and Yoga as Medicine for Labor and Postpartum. Check out her poster at the Combined Sections Meeting this weekend in Anaheim!

Maternal health care in the United States is abysmal. Especially wretched is care and support of women post-partum. Our insurance system is partially to blame by dictating that women receive only one visit with the provider who participated in the delivery of their baby 6 weeks after the baby is born, no matter the method of delivery. This is often after most of the scary, unexpected side effects of delivery, like heavy bleeding, nipple pain, urinary incontinence, difficulty with bowel movements, scar pain and tremendous mood swings have begun to ease. Only the women who are the most persistent, or those who have chosen unique care models (like out of hospital births with midwives), seem to get real support post-partum, leaving marginalized and less self-driven women to fend for themselves.

What if research could show that immediately treating some of the side effects of birth, like diastasis recti abdominus, which occurs in 50-60% of post-partum women, could result in improved outcomes in the long run? What if someone could prove that retraining and strengthening the abdominal wall as part of a biopsychosocial model empowering women could change the costly effects of prolapse and urinary incontinence treatment later on in life? What if that research aimed to show that treating women in partnership will all care providers was the most effective? These are big questions, but through research beginning with Diastasis Recti Abdominis (DRA), some Women’s Health Physical Therapists trained in Medical Therapeutic Yoga are hoping to highlight some answers.

At CSM in San Diego next month, these researchers (listed below) are presenting a poster via the Section on Women’s Health showcasing their paper, Diastasis Recti Abdominis: A Narrative Review. They found that good, solid research focusing on the co-morbidities and treatment of DRA is really lacking. Most well-done studies focus on the reliability and validity of measurement techniques, showing that calipers and ultrasound are the most valid and reliable ways to measure the gap. There is not even agreement on what precise measurement technically constitutes a DRA, though most agree that normal inter-recti distance is 15-25mm supraumbilically among parous females with digital calipers. (Chiarello 2013).

Besides the obvious cosmetic and general strengthening concerns, why do we care about physical therapy care for a post-partum DRA? Spitznagle’s retrospective chart review of women presenting for gynecological care with a mean age of 52 found that 52% had DRA and 66% of them had a least one support-related pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. Those with DRA were more likely to have pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence and fecal incontinence. Another study by Parker found a DRA prevalence of 74.4% among women with back or pelvic area pain who had delivered at least one child and sought PT. They found a significant difference in VAS pain levels in those with DRA and abdominal or pelvic pain compared to those without DRA. More well-done, prospective studies are really needed to correlate these sequalea in later life to DRA post-partum.

The topic of how to retrain the abdominal wall to restore optimal function and cosmetic appearance is hot in the blogosphere right now. Does it matter if the width of the diastasis recti is reduced? Or is it a matter of having tension in the linea alba as the clinician sinks his/her fingers toward the spine? Biomechanically we know that in order to improve stiffness in the trunk, we need synergistic and symmetrical firing of the diaphragm, transversus abdominis, multifidus and the pelvic floor with proper timing and contraction of the hip and external abdominal muscles. Benjamin completed a review of the research on the effects of exercise in the antenatal and postnatal periods and concluded that antenatal exercise may be protective against the formation of a DRA, but that the available studies are of such poor quality and varied in the way that abdominal/core strengthening was applied in the post-partum population, that it is impossible to tell how or why exercise may or may not help with DRA!

There is clearly a huge hole in the literature and as usual, new mothers are suffering. Women are spending money on programs they find on the internet that are not backed by solid research, because there is not any! Regarding DRA, post-partum women in our country desperately need well-done, high quality studies promoting a specific and well-described exercise for healing. In addition, in our patriarchal health care model, we need to show without a shadow of a doubt that treating post-partum muscle weakness, body mechanics issues and DRA is essential for saving money in the long run on prolapse and urinary incontinence surgery, as well as decreasing expenditure on back pain treatments.

If our discipline could provide this research, ALL women could have access to personal, post-partum recovery. As an established part of the health care system and with longer treatment times and the chance to get to know our patients better, physical therapists are the IDEAL healthcare practitioners to ensure that post-partum women are getting adequate physical retraining, but also psycho-social support that is so lacking in the United States.

The Women’s Health Poster Presentations at CSM in Anaheim will be on Saturday, Feb 20 from 1-3PM. I look forward to meeting with some of you and visiting about what you are working on to further the cause of improving maternal health care and DRA treatment.

Ginger Garner PT, ATC, PYT, Professional Yoga Therapy Institute, Emerald Isle, NC

Elizabeth Trausch, DPT, PYT Des Moines University, Des Moines IA

Stefanie Foster, PT, PYT Asana with Intelligence, Houston, TX

Paige Raffo, PT, PYT, CPI, Balance+Flow Physio, Bellevue, WA

Janet Drake, PT, LCCE, FACCE, PYT, Central Bucks Physical Therapy, Doylestown, PA

Stacie Razzino, PT, PYT, Free Motion Physical Therapy, Melbourne, FL

Blog post by Libby Trausch, DPT

Spitznagle T, Leong F, Van Dillen L, Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in a urogynecological patient population, International Urogynecology Journal. 2007; 18: 321-328.

Chiarello CM, Mcauley JA. Concurrent validity of calipers and ultrasound imaging to measure interrecti distance. Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013; 43(7): 495-503

Benjamin DR, et al., Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014 Mar;100(1):1-8.

Exercise in pregnancy is a loaded topic. We commonly see images of women doing vigorous exercise in late pregnancy accompanied by judgmental statements about the safety of such activity not only for the woman, but also for the baby. Many myths persist about exercise in pregnancy, and it’s our role as health care specialists to educate women about what is known about exercising. Holly Herman, co-founder of the Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute, has been educating providers about this topic for most of her career. Anyone lucky enough to take a course on pregnancy and postpartum issues from Holly Herman knows that her style of teaching is effective and her passion is contagious. From Holly’s use of patient stories to wonderful humor, you can really “get it” when it comes to clinical concepts and strategies. One of Holly’s clinical pearls that really stuck with me after learning about exercise and pregnancy is the research completed by James Clapp in his book “Exercise in Pregnancy”. In short, the book dispels the myth that women shouldn’t exercise in pregnancy and in fact reports on the benefits of exercise to both Mom and baby for labor, delivery, and beyond. In signature style, Holly held this book up in front of the class and to great laughter said, “And this is the book you should buy for your mother-in-law.”

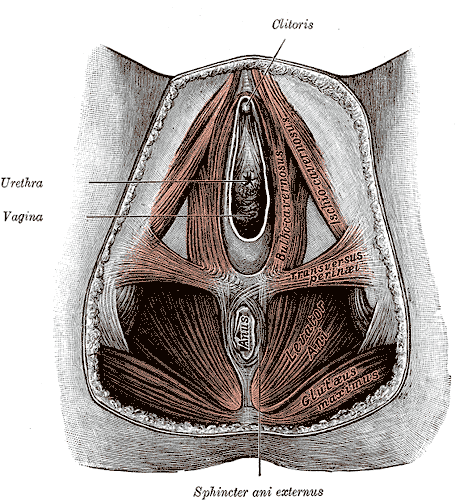

Another myth that has been perpetuated in relation to pregnancy, labor and delivery is the notion that exercising can make the pelvic floor muscles short, tight, and more narrow, making delivery more difficult. In an article we reported on previously about women being “too tight to give birth” the authors concluded that strong pelvic floor muscles do not lead to challenges with birthing. (Bo et al., 2013) In a more recent article that addressed this issue, Kari Bo and colleagues studied 274 women for levator hiatus (LH) width to see if exercising in late pregnancy did in fact narrow this space. At week 37 of gestation, the exercisers were measured to have a significantly larger LH than the non-exercisers. (Exercisers were defined as women who exercised 30 minutes or more 3 times per week versus the non-exercisers.) The authors conclude that there were not any significant differences in labor outcomes or in delivery outcomes between the groups. (Bo et al., 2015)

Another myth that has been perpetuated in relation to pregnancy, labor and delivery is the notion that exercising can make the pelvic floor muscles short, tight, and more narrow, making delivery more difficult. In an article we reported on previously about women being “too tight to give birth” the authors concluded that strong pelvic floor muscles do not lead to challenges with birthing. (Bo et al., 2013) In a more recent article that addressed this issue, Kari Bo and colleagues studied 274 women for levator hiatus (LH) width to see if exercising in late pregnancy did in fact narrow this space. At week 37 of gestation, the exercisers were measured to have a significantly larger LH than the non-exercisers. (Exercisers were defined as women who exercised 30 minutes or more 3 times per week versus the non-exercisers.) The authors conclude that there were not any significant differences in labor outcomes or in delivery outcomes between the groups. (Bo et al., 2015)

Without a doubt, the patient’s obstetrician gives primary direction to the patient when any high-risk issues are present. Most women however, are basing their exercise choices on experience, on misinformation, myths, or popular opinion. It is our responsibility to engage women in conversations about her health, wellness, and fitness, and to appropriately counsel on exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Most of us lacked proper education about this important population in our primary graduate training, and therefore must seek out information to fill in the gaps. If you are interested in filling in any gaps, join us at one of our peripartum courses around the country. Your next opportunities to take these courses are:

Care of the Postpartum Patient - Seattle, WA

Mar 12, 2016 - Mar 13, 2016

Care of the Pregnant Patient - Somerset, NJ

Apr 30, 2016 - May 1, 2016

Care of the Pregnant Patient - Akron, OH

Sep 10, 2016 - Sep 11, 2016

Bø, K., Hilde, G., Jensen, J. S., Siafarikas, F., & Engh, M. E. (2013). Too tight to give birth? Assessment of pelvic floor muscle function in 277 nulliparous pregnant women. International urogynecology journal, 24(12), 2065-2070.

Bø, K., Hilde, G., Stær-Jensen, J., Siafarikas, F., Tennfjord, M. K., & Engh, M. E. (2015). Does general exercise training before and during pregnancy influence the pelvic floor “opening” and delivery outcome? A 3D/4D ultrasound study following nulliparous pregnant women from mid-pregnancy to childbirth. British journal of sports medicine, 49(3), 196-199.

Clapp, J. F., Cram, C. (2012) Exercising Through Your Pregnancy. Addicts Books

Occasionally, as pelvic rehab providers, we will encounter the question from our patients, “Do vaginal weights help with urinary incontinence and pelvic floor performance?” The premise behind the use of vaginal cones or balls is that holding them actively in your vagina with your pelvic floor muscles helps to increase the performance (strength and endurance) of the pelvic floor muscles, assisting in reduction of urinary incontinence.

Of the searched studies, all were randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials. The primary outcomes of the searched studies were pelvic floor muscle performance (strength or endurance) and/or urinary incontinence, both assessed with a valid or reliable method. 37 potentially useful articles were reviewed out of 1324 based on the search criteria, but only one article met all of the inclusion criteria and was included in this review with 192 relevant participants (Wilson and Herbison).

In the included study, the group that used vaginal cones (compared to control group) showed a statistically significant lower rate of urinary incontinence. However, when compared to the pelvic exercises group, the continence rates were similar at 12 months post-partum between the cone group and the exercising group. At 24-44 months post-partum, continence rates amongst all groups were similar, but follow-up rates were very low.

As pelvic rehabilitation providers, it is our job to promote pelvic health and assist our post-partum patients with their pelvic impairments, providing them with options to meet their goals. This review does not make a scientific statement of a preferred mode of pelvic exercise, however, it gives us one more option to consider when teaching patients about how to improve pelvic muscle performance to increase urinary continence following child birth. Pelvic exercise enhances pelvic performance, so if your patient would prefer to use vaginal cones or balls to do their pelvic exercise versus completing pelvic exercises without them, do what works best for the patient. One can argue that any pelvic exercise is better than none in improving performance. The use of vaginal cones or balls may be helpful for urinary continence in post-partum women, and provides us with one tool more when promoting pelvic health in our patients.

Oblasser, C., Christie, J., & McCourt, C. (2015). Vaginal cones or balls to improve pelvic floor muscle performance and urinary continence in women post-partum: A quantitative systematic review. Midwifery, 31(11), 1017-1025.

Wilson, P. D., & Herbison, G. P. (1998). A randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle exercises to treat postnatal urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal, 9(5), 257-264.

Episiotomy is defined as an incision in the perineum and vagina to allow for sufficient clearance during birth. The concept of episiotomy with vaginal birth has been used since the mid to late 1700’s and started to become more popular in the United States in the early 1900’s. Episiotomy was routinely used and very common in approximately 25% of all vaginal births in the United States in 2004. However, in 2006, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended against use of routine episiotomies due to the increased risk of perineal laceration injuries, incontinence, and pelvic pain. With this being said, there is much debate about their use and if there is any need at all to complete episiotomy with vaginal birth.

What are the negative outcomes of episiotomy?

What are the negative outcomes of episiotomy?

The primary risks are severe perineal laceration injuries, bowel or bladder incontinence, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and pelvic floor laxity. Use of a midline episiotomy and use of forceps are associated with severe perineal laceration injury. However, mediolateral episiotomies have been indicated as an independent risk factor for 3rd and 4th degree perineal tears. If episiotomy is used, research indicates that a correctly angled (60 degrees from midline) mediolateral incision is preferred to protect from tearing into the external anal sphincter, and potentially increasing likelihood for anal incontinence.

What are the indications for episiotomy, if any?

This remains controversial. Some argue that episiotomies may be necessary to facilitate difficult child birth situations or to avoid severe maternal lacerations. Examples of when episiotomy may be used could include shoulder dystocia (a dangerous childbirth emergency where the head is delivered but the anterior shoulder is unable to pass by the pubic symphysis and can result in fetal demise.), rigid perineum, prolonged second stage of delivery with non reassuring fetal heart rate, and instrumented delivery.

On the other side of the fence, many advocate never using an episiotomy due to the previously stated outcomes leading to perineal and pelvic floor morbidity. In a recent cohort study in 2015 by Amorim et al., the question of “is it possible to never perform episiotomy with vaginal birth?” was explored. 400 women who had vaginal deliveries were assessed following birth for perineum condition and care satisfaction. During the birth there was a strict no episiotomy policy and Valsalva, direct pushing, and fundal pressure were avoided, and perineal massage and warm compresses were used. In this study there were no women who sustained 3rd or 4th degree perineal tears and 56% of the women had completely intact perineum. 96% of the women in the study responded that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their care. The authors concluded that it is possible to reach a rate of no episiotomies needed, which could result in reduced need for suturing, decreased severe perineal lacerations, and a high frequency of intact perineum’s following vaginal delivery.

Are episiotomies actually being performed less routinely since the 2006 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendation?

Yes, a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association by Friedman, it showed that the routine use of episiotomy with vaginal birth has declined over time likely reflecting an adoption of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations. This is ideal, as it remains well established that episiotomy should not be used routinely. However, indications for episiotomy use remain to be established. Currently, physicians use clinical judgement to decide if episiotomy is indicated in specific fetal-maternal situations. If one does receive an episiotomy then a mediolateral incision is preferred. The World Health Organization’s stance is that an acceptable global rate for the use of episiotomy is 10% or less of vaginal births. So the question still remains, (and of course more research is needed) to episiotomy or not to episiotomy?

Amorim, M. M., Franca-Neto, A. H., Leal, N. V., Melo, F. O., Maia, S. B., & Alves, J. N. (2014). Is It Possible to Never Perform Episiotomy During Vaginal Delivery?. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 123, 38S.

Friedman, A. M., Ananth, C. V., Prendergast, E., D’Alton, M. E., & Wright, J. D. (2015). Variation in and Factors Associated With Use of Episiotomy. JAMA, 313(2), 197-199.

Levine, E. M., Bannon, K., Fernandez, C. M., & Locher, S. (2015). Impact of Episiotomy at Vaginal Delivery. J Preg Child Health, 2(181), 2.

Melo, I., Katz, L., Coutinho, I., & Amorim, M. M. (2014). Selective episiotomy vs. implementation of a non episiotomy protocol: a randomized clinical trial. Reproductive health, 11(1), 66.

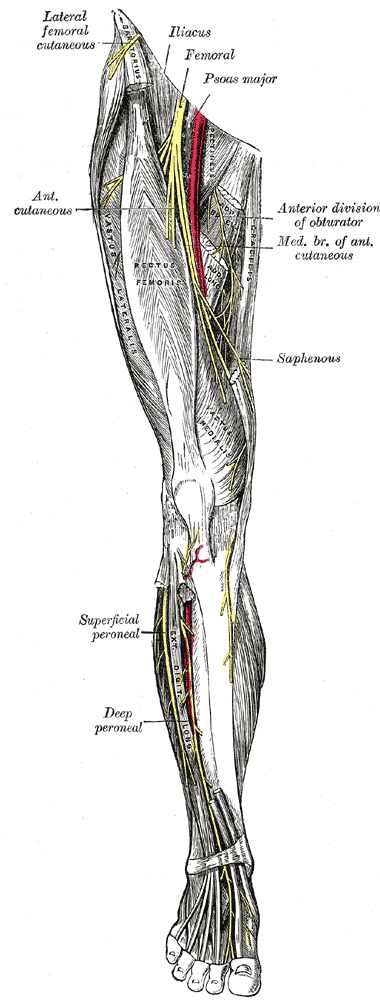

Postpartum lower extremity nerve injuries is an important topic that we have previously discussed on the blog. A review article(O'Neal 2015) published in the International Anesthesia Research Society journal discusses maternal neurological complications following childbirth. This article, designed to help anesthesiologists identify the symptoms of a neuropathy, discusses diagnosis, management, and treatment. With the incidence of obstetric neuropathy in the postpartum period estimated at 1%, most of the nerve dysfunction is related to compression injuries. Symptoms may include, but are not limited to, lower extremity pain, weakness, numbness, or bowel and bladder dysfunction. Neuraxial anesthesia can also occur, with issues such as epidural hematoma or an epidural abscess. Risk factors are described in the article as having a prolonged second stage of labor, instrumented delivery, being of short stature and nulliparity (delivering for the first time.)

Clinical pearls listed in the article include the following information that may be helpful in understanding a patient’s condition:

Clinical pearls listed in the article include the following information that may be helpful in understanding a patient’s condition:

- intramedullary spinal cord syndromes (inside the spinal cord) are usually painless, whereas the peripheral nerve syndromes (involving the spinal nerve roots, plexus, and single nerves) usually cause pain

- bowel and bladder dysfunction often occurs early in the case of conus medullaris and late in the event of cauda equina syndrome

- cauda equina syndrome often causes polyradicular pain, leg weakness, numbness, and deep tendon reflex changes and involves multiple roots

- conus medullaris syndrome is not painful and causes saddle anesthesia and lack of significant sensory and motor symptoms in the lower extremities

In relation to prevention of neuropathies, the authors suggest that women who have diabetes or who have a preexisting neuropathy should be given extra attention. This may include protective padding during labor and delivery as well as frequent repositioning. Pelvic rehabilitation providers are a key player in the arena of birthing. Caring for women and educating them about peripartum issues is critical to helping women both prevent and heal from challenges encountered in relation to pregnancy and childbirth. If you would like to learn more about the topic of peripartum nerve dysfunctions, as well as many other special topics, please join us for the continuing education course Care of the Postpartum Patient. Your next opportunity to take this course will be in Seattle next March!

O’Neal, M. A., Chang, L. Y., & Salajegheh, M. K. (2015). Postpartum Spinal Cord, Root, Plexus and Peripheral Nerve Injuries Involving the Lower Extremities: A Practical Approach. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 120(1), 141-148.

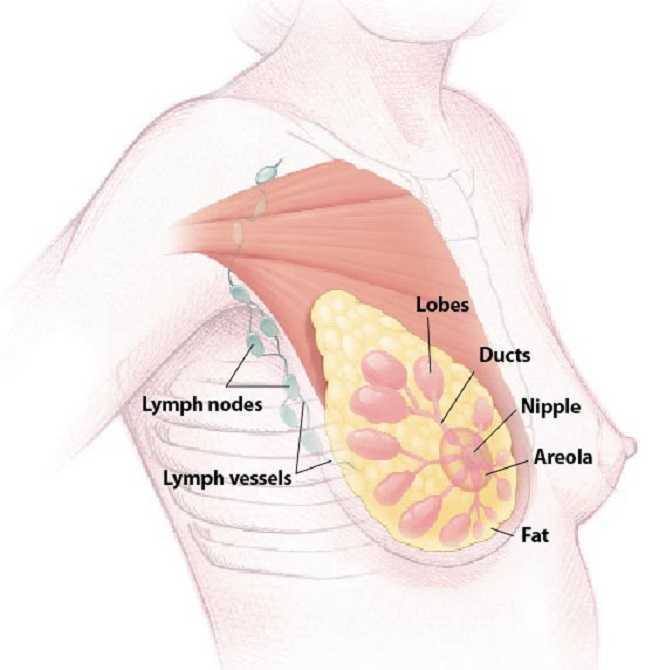

Milk duct blockage is a common condition in breast feeding mother’s that can cause a multitude of problems including painful breasts, mastitis, breast abscess, decreased milk supply, breast feeding cessation, and poor confidence with decreased quality of life. A recent study in 2015 in The Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1, showed that physical therapy (PT) maybe a helpful treatment for the lactating mother experiencing milk duct blockage when conservative measures have failed. Common conservative measures typically recommended are self-massage, heat, and regular feedings. The World Health Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and Academy of Breast Feeding Medicine, all recommend breast feeding as the primary source for nutrition for infants. There are many benefits to both the mother, and the infant, when breast feeding is used as the primary source for nutrition in infants. Having blocked milk ducts make it difficult and painful to breast feed and can lead to poor confidence for the mother and a frustrated baby as the milk supply could be reduced or inadequate. The primary health concern for blocked milk ducts is mastitis. Mastitis is defined as an infection of breast tissue leading to pain, redness, swelling, and warmth, possibly fever and chills and can lead to early cessation of breast feeding.

A blocked milk duct is not a typical referral to PT, however, this study outlined a protocol used for 30 patients with one or more blocked milk ducts that were referred to PT by a qualified lactation consultant. This study was a prospective pre/posttest cohort study. As an outcome measure, this study utilized a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for 3 descriptive areas: pain, difficulty breast feeding, and confidence in independently nursing before and after treatment. The treatment protocol included moist heat, thermal ultrasound, specific manual therapy techniques, and patient education for treatment and prevention of the blockage(s). The thermal ultrasound and moist heating provided the recommend amount of heat to relax tissue around the blockage. Ultrasound also provided a mechanical effect that assists in the breaking up of the clog and increased pain threshold for the patient to improve tolerance to the manual clearing techniques. Next, the specific manual therapy was provided to directly unclog the blockage(s), and lastly the education provided was to help the patient identify and clear future blockages to prevent recurrence. 22 of the 30 patients were seen for 1-2 visits, 6 were seen for 3-4 visits, and none of the mother’s condition progressed to infective mastitis or developed breast abscess’s.

A blocked milk duct is not a typical referral to PT, however, this study outlined a protocol used for 30 patients with one or more blocked milk ducts that were referred to PT by a qualified lactation consultant. This study was a prospective pre/posttest cohort study. As an outcome measure, this study utilized a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for 3 descriptive areas: pain, difficulty breast feeding, and confidence in independently nursing before and after treatment. The treatment protocol included moist heat, thermal ultrasound, specific manual therapy techniques, and patient education for treatment and prevention of the blockage(s). The thermal ultrasound and moist heating provided the recommend amount of heat to relax tissue around the blockage. Ultrasound also provided a mechanical effect that assists in the breaking up of the clog and increased pain threshold for the patient to improve tolerance to the manual clearing techniques. Next, the specific manual therapy was provided to directly unclog the blockage(s), and lastly the education provided was to help the patient identify and clear future blockages to prevent recurrence. 22 of the 30 patients were seen for 1-2 visits, 6 were seen for 3-4 visits, and none of the mother’s condition progressed to infective mastitis or developed breast abscess’s.

The results of the study showed the protocol used was helpful to ease pain, reduce difficulty with breast feeding, and improve confidence with independent breast feeding for lactating women that participated in the study. Although treatment of blocked milk ducts in lactating mothers is not a common PT referral, this study shows that PT may be one more helpful treatment for a patient experiencing this problem that is not responding to traditional conservative treatment. Since breast feeding is important to both mother and infant and is the primary recommended source for infant nutrition, it is important that a lactating mother receives quick, effective treatment for blocked milk ducts to prevent onset of mastitis and breast abscess that lead to early cessation of breast feeding. The cited study recommends that women who suspect a blocked milk duct or are having problems with breast feeding always seek care from a certified lactation consultant first, and that PT may be a referral that is made.

Cooper, B. B., & Kowalsky, D. S. (2015). Physical Therapy Intervention for Treatment of Blocked Milk Ducts in Lactating Women. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 39(3), 115-126.

The eve of my daughter’s 5th birthday has me reminiscing about my first pregnancy. I had recently surrendered my ACL on a ski slope and was contemplating surgery when I got confirmation I was pregnant. A seasoned surgeon had told me if I just wanted to return to running and not ski or do cutting sports (without a brace, anyway), I would probably be fine; so, I chose to forego the surgery and was running again 7 weeks later. Being my first pregnancy, I was not sure how hormones would affect my knee stability without an ACL or if the impact was safe for me and the baby or if my doctor would approve of my exercise choice of running. After all, pending ligamentous laxity from hormonal changes made running without an ACL seem risky while pregnant; but, runners tend to be, well, stubborn, when it comes to being able to run.

Deghan et al (2014) discuss the hormone relaxin and its effect on bone, muscle, tendon, ligaments, and cartilage. Interestingly, relaxin actually plays a role in the healing and remodeling of certain tissues in the body such as muscle and bone. However, the article also emphasizes how relaxin has been shown to reduce the integrity of the ACL and put female athletes at risk for injury. Lucky for me, that hormone couldn’t have its way with my knee since the ACL was already gone!

Deghan et al (2014) discuss the hormone relaxin and its effect on bone, muscle, tendon, ligaments, and cartilage. Interestingly, relaxin actually plays a role in the healing and remodeling of certain tissues in the body such as muscle and bone. However, the article also emphasizes how relaxin has been shown to reduce the integrity of the ACL and put female athletes at risk for injury. Lucky for me, that hormone couldn’t have its way with my knee since the ACL was already gone!

A study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine just published online October 4, 2015, encourages running and other high-impact sports before pregnancy to decrease the risk of pelvic girdle pain. The patients engaging in such exercises prior to being pregnant showed a 14% lower risk of having pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy. Out of 4069 women, 12.5% of the 10.4% of women who experienced pelvic pain were non-exercisers pre-pregnancy. The women who exercised 3-5 days per week and participated in high-impact aerobic exercise prior to being pregnant had less pelvic pain while pregnant.

Tenforde et al (2015) investigated the habits of competitive runners during pregnancy as well as breastfeeding. Out of 110 female runners, 70% continued to run during their pregnancy; however, only 31% continued into their 3rd trimester. Only 3.9% of the women got injured while running pregnant. In general, the competitive runners reduced their intensity and volume and ran primarily for fitness and health. The 84.1% of the women who ran during breastfeeding reported less postpartum depression and no negative impact on breastfeeding.

Looking back at my running log, I ran 3 miles under 10-minute pace two days before going into labor, and my daughter was even 9 days late. I continued to run because I love it and, quite simply, because I could. Personally, my blood pressure, weight, and glucose levels stayed healthy throughout the pregnancy. Even without an important stabilizing ligament in my knee and some extra pounds, I never experienced joint pain while running. On the trail where I ran, I got mixed responses from people coming the other way - mostly encouragement, but also some looks of disappointment or disgust (I didn’t say it was pretty) and an occasional know-it-all “warning.” Ultimately, any woman who has been running prior to pregnancy should be able to continue some level of running through the trimesters until her own body, the obstetrician, or a hard-kicking baby gives a reason to stop.

Dehghan, F., Haerian, B. S., Muniandy, S., Yusof, A., Dragoo, J. L., & Salleh, N. (2014). The effect of relaxin on the musculoskeletal system. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 24(4), e220–e229. http://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12149

Owe KM, Bjelland EK, Stuge B, Orsini N, Eberhard-Gran M, Vangen S. (4 October 2015). Exercise level before pregnancy and engaging in high-impact sports reduce the risk of pelvic girdle pain: a population-based cohort study of 39,184 women. British Journal of Sports Medicine. pii: bjsports-2015-094921. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094921. [Epub ahead of print]

Tenforde AS, Toth KE, Langen E, Fredericson M, Sainani KL. (2015 Mar). Running habits of competitive runners during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Sports Health.;7(2):172-6. doi: 10.1177/1941738114549542.

Postpartum perineal injuries can cause pain and dysfunction for a short or an extended period of time. Pelvic rehab providers are in a position to educate women about the immediate and long-term management of perineal pain. A 2015 study by Manfre et al. assessed the response of cortisone cream application to the perineum in the immediate postpartum period. The study was a randomized controlled trial involving 27 subjects with each subject serving as her own control. Three different treatments were given over a 12 hour period: corticosteroid, placebo, and no treatment. (The hydrocortisone cream was at 1% in an alcohol-based cream, the placebo was a non-medicated acetyl alcohol-based cream.) The cream was applied by an investigator who placed the cream on a Witch Hazel pad. The participants and the researchers were blinded to the type of cream applied, and the applications were randomized and took place within the first 12.5 hours after birth. Perineal pain levels were assessed immediately before cream application, and at 30 and 60 minutes after application. Using a visual analog scale (VAS), the symptom of pain was assessed and compared to baseline. In the study, the authors report that in the immediate postpartum period, women in their institution were often prescribed medication ranging from ibuprofen to hydrocodone. Topical medications, ice packs, heat packs are also mentioned as available treatments. Other pain medications or cold packs were available during the study; no other topical creams were utilized.

Results indicated that the participants responded positively to both creams with significantly more pain reduction than the no treatment group. The authors propose that both creams provided a soothing effect by providing moisture to the tissues, creating a protective barrier, and preventing friction and irritation. Because the placebo emollient cream was not significantly more expensive than the hydrocortisone cream, the article suggests using hydrocortisone on the postpartum perineum due to the medication’s potential beneficial anti-inflammatory effects. Also of note was that ice packs were used by less than half of the women in the study, and when ice was used, it was only during the first four hours after birth. One reason for the low frequency use of ice was thought to be the difficulty in maintaining ice application on the perineum.Manfre 2015

Results indicated that the participants responded positively to both creams with significantly more pain reduction than the no treatment group. The authors propose that both creams provided a soothing effect by providing moisture to the tissues, creating a protective barrier, and preventing friction and irritation. Because the placebo emollient cream was not significantly more expensive than the hydrocortisone cream, the article suggests using hydrocortisone on the postpartum perineum due to the medication’s potential beneficial anti-inflammatory effects. Also of note was that ice packs were used by less than half of the women in the study, and when ice was used, it was only during the first four hours after birth. One reason for the low frequency use of ice was thought to be the difficulty in maintaining ice application on the perineum.Manfre 2015

Because the pelvic rehab provider is in an optimal role as educator for pain reduction strategies, this study provides some interesting information to share with other birth providers and with patients. Learn more about postpartum patient care at Care of the Postpartum Patient, available in Seattle this March.

Manfre, M., Adams, D., Callahan, G., Gould, P., Lang, S., McCubbins, H., ... & Chulay, M. (2015). Hydrocortisone Cream to Reduce Perineal Pain after Vaginal Birth: A Randomized Controlled Trial. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 40(5), 306-312.

Diastasis of the Rectus Abdominis Muscle (DRAM) is the separation of the two rectus abdominis muscles along the linea alba and is very common during and after pregnancy as the rectus abdominis and linea alba stretches and thins. Patients with DRAM are often sent to seek non-surgical management for DRAM from a physical therapist (PT). Typically these patients are either at the end of their pregnancy or adjusting to round the clock care of an infant. They can be sleep deprived, and have a full schedule of doctor’s appointments, having difficulty finding childcare, making attending PT somewhat challenging. Furthermore, they may have difficulty finding the time for a home exercise program (HEP). As PT’s we often struggle with making sure to give the patient exercises that will accomplish the goal of improving DRAM, however, making sure the HEP is not so extensive or time consuming that it becomes unmanageable. Is something as easy as abdominal bracing with exercise effective for reducing DRAM in post-partum women? A recent study published in 2015 in the International Journal of Physiotherapy and Research explores just this topic(Acharry).

Why is Diastasis of the Rectus Abdominis Muscle (DRAM) important?

Women with DRAM tend to have a higher degree of abdominal and pelvic region pain(Parker). Also women with DRAM may be more likely to have support related pelvic floor problem such stress urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, or pelvic organ prolapse. The linea alba and rectus abdominis play an integral role in maintaining the anterior support of the trunk, these structures work together with pelvic girdle, posterior trunk muscles, and hips in maintaining stability when we shift weight (or transfer load) such as with standing, squatting, walking, carrying, and lifting. Therefore postural stability may be impaired with these daily tasks. Lastly, the abdominal muscles and fascia protect and support our organs so women with DRAM may have compromised support and protection of visceral structures.

Women with DRAM tend to have a higher degree of abdominal and pelvic region pain(Parker). Also women with DRAM may be more likely to have support related pelvic floor problem such stress urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, or pelvic organ prolapse. The linea alba and rectus abdominis play an integral role in maintaining the anterior support of the trunk, these structures work together with pelvic girdle, posterior trunk muscles, and hips in maintaining stability when we shift weight (or transfer load) such as with standing, squatting, walking, carrying, and lifting. Therefore postural stability may be impaired with these daily tasks. Lastly, the abdominal muscles and fascia protect and support our organs so women with DRAM may have compromised support and protection of visceral structures.

Is DRAM common?

Pregnancy is the most common cause of DRAM and studies widely range from 50-100% of women experiencing DRAM at end stage pregnancy. Natural reduction and greatest recovery of DRAM usually occurs between day 1 and week 8 after delivery. Various ways exist to diagnose DRAM. The gold standard for diagnosis is computed tomography but is sometimes considered impractical due to expense. Clinically a separation of 2.0-2.7cm or “two finger widths” of horizontal separation at the umbilicus or 4.5cm above or below while performing a hooklying (supine with knees bent) abdominal curl up is considered pathological separation.

What can be done for DRAM?

Current guidelines for conservative treatment of DRAM are sparse with little established recommendations. The earlier referenced recent cross sectional study(Acharry) explores efficacy of abdominal bracing as a treatment for reduction of DRAM in post-partum females. The study included 30 females that were one month post-partum or more who had vaginal delivery with or without episiotomy. The average distance of the diastasis was measured before and after treatment using the finger width technique. The treatment included teaching the subject four abdominal exercises, and the subjects were encouraged to complete abdominal bracing while carrying out daily activities. The four exercises included 1) static abdominal bracing exercise, lying supine with arms crossed over the diastasis for support and then pulling abdominals inwards with an isometric contraction of abdominal muscles. 2) Head lift with bracing, in hooklying with arms crossed over diastasis, exhale, lift head and use hands (or a towel/sheet) to approximate diastasis towards midline. 3) Head lift and pelvic tilt with bracing, is the same as previous exercise only adding a posterior pelvic tilt. 4) Pelvic clock exercise with bracing, visualize a clock on the lower abdominals and complete gentle movements from 12-6 o’clock, 3-9 o’clock, 12-3-6-9-12 o’clock, in a clockwise fashion and then reverse the pattern in a counter clockwise pattern. All exercises were performed twice daily, with a repetition of 5-6 days per week, for 2 weeks duration. After completing the program for two weeks the distance of the diastasis was re-measured and the average DRAM distance decreased from 3.5 to 2.5 finger widths which was considered significant. The results of this study show abdominal exercise with bracing is effective for reducing DRAM in early post partal females.

As PT’s who treat DRAM we should encourage our patients to use abdominal exercises with bracing as well as encourage our patients to use abdominal bracing with their daily tasks such as standing, lifting, weight shifting, and carrying. A home exercise program such as the one in this study proved to be effective for reducing DRAM and included only four exercises making this a manageable home exercise program for our post-partum patients.

Herman & Wallace offers a full series of peripartum courses called the "Pregnancy Series". To learn more about diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle, join Holly Tanner, PT, DPT, MA, OCS, WCS, PRPC, LMP, BCB-PMB, CCI at Care of the Postpartum Patient in Seattle, WA this March 12-13, 2016!

Acharry, N., & Kutty, R. K. (2015). ABDOMINAL EXERCISE WITH BRACING, A THERAPEUTIC EFFICACY IN REDUCING DIASTASIS-RECTI AMONG POSTPARTAL FEMALES. Int J Physiother Res, 3(2), 999-05.

Parker, M. A., Millar, L. A., & Dugan, S. A. (2009). Diastasis Rectus Abdominis and Lumbo‐Pelvic Pain and Dysfunction‐Are They Related?. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 33(2), 15-22.