A recent article in the Washington Post Health & Science section explored the wonders of dietary fibre in an article called ‘Fiber has surprising anti-aging benefits, but most people don’t eat enough of it’ The article discussed how ‘…Fiber gets well-deserved credit for keeping the digestive system in good working order — but it does plenty more. In fact, it’s a major player in so many of your body’s systems that getting enough can actually help keep you youthful. Older people who ate fiber-rich diets were 80 percent more likely to live longer and stay healthier than those who didn’t, according to a recent study in the Journals of Gerontology’

But what is fiber and why does it matter?

Before we jump in there, let me answer the perennial questions that arise when we, as pelvic rehab clinicians, talk about fiber…’Is it in our scope of practice to talk about food?!’ I think it is fundamental that if we are placing ourselves as experts in bladder and bowel dysfunction, that we also remember that we can’t focus on problems at one end of ‘the tube’ without thinking about what happens at the other end. Furthermore, let me quote the APTA RC 12-15: The Role of the Physical Therapist in Diet and Nutrition. (June 2015): “as diet and nutrition are key components of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of many conditions managed by physical therapists, it is the role of the physical therapist to evaluate for and provide information on diet and nutritional issues to patient, clients, and the community within the scope of physical therapist practice. This includes appropriate referrals to nutrition and dietary medical professionals when the required advice and education lie outside the education level of the physical therapist’’

Fiber plays a huge role in so many of the health issues that we as clinicians face daily – constipation is regarded as a scourge of a modern sedentary society, perhaps over-reliant on processed convenience food – this is borne out when we gaze upon the rows of constipation remedies and laxatives in our pharmacies and supermarkets.

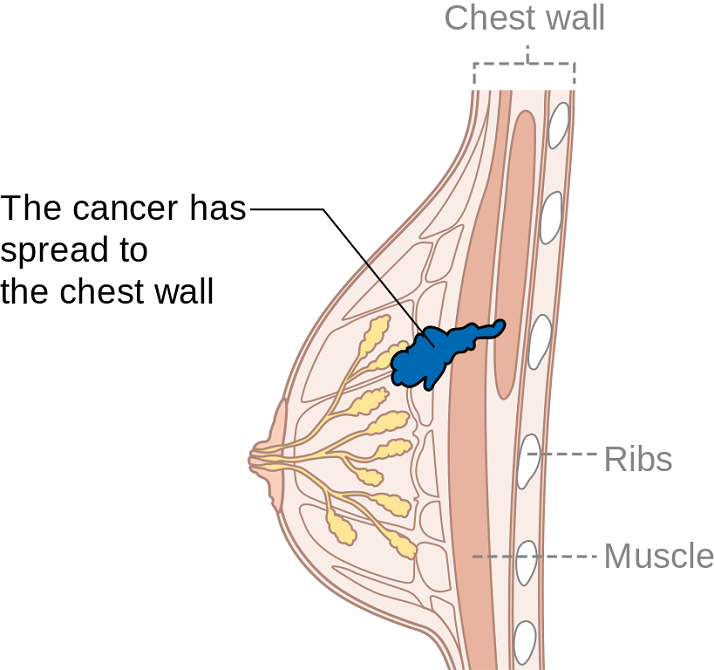

Let's take a look at the effects of fiber on breast cancer recovery – what does the research say?

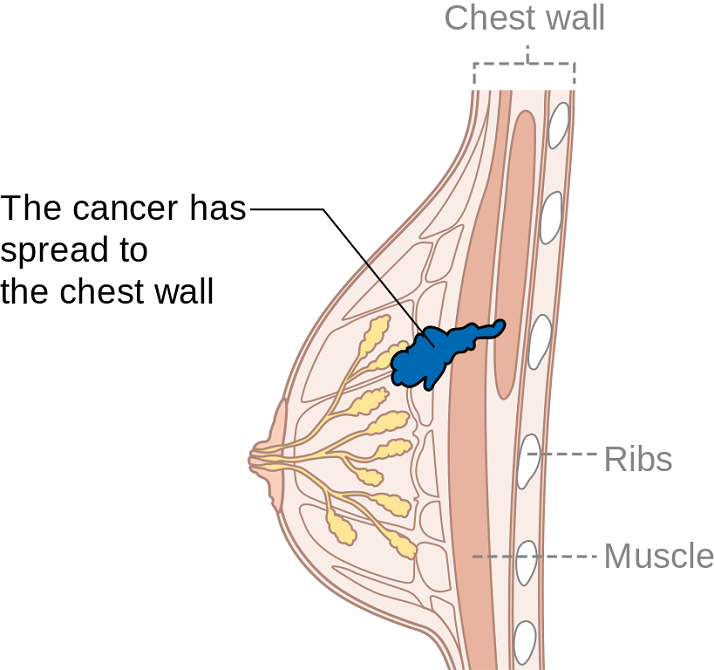

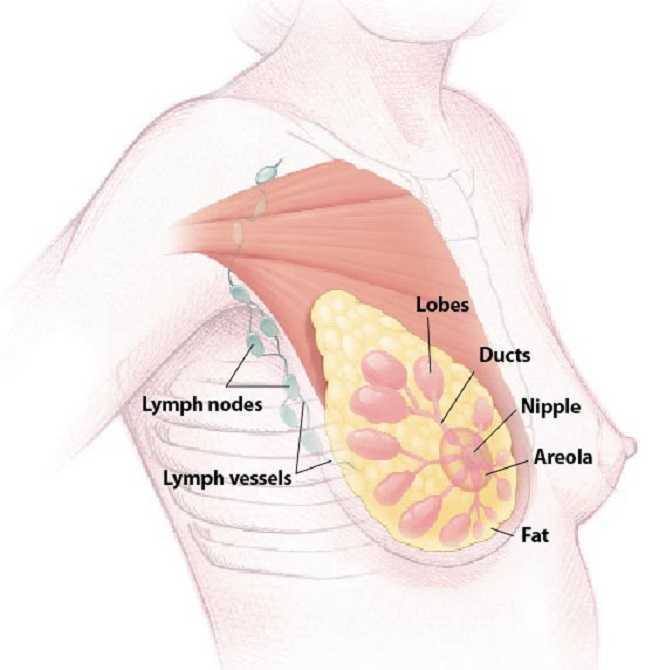

There is growing interest and evidence to suggest that making different food choices can help control symptoms of breast cancer treatment and improve recovery markers – avoiding food with added sugar, hydrating well and focusing primarily on plant based food. Fiber is of course beneficial for bowel health, but may also have added benefits for heart health, managing insulin resistance, preventing excess weight gain and actually helping the body to excrete excess estrogen, which is often a driver for hormonally sensitive cancers. Fiber may be Insoluble (whole grains, vegetables) or Soluble (oats, rice, beans, fruit) but both are essential and variety is best.

In their paper ‘Diets and Hormonal levels in Post menopausal women with or without Breast Cancer’ Aubertin – Leheudre et al (2011) stated that ‘…Women eating a vegetarian diet may have lower breast cancer because of improved elimination of excess estrogen’, but even prior to that, in ‘Estrogen excretion patterns and plasma levels in vegetarian and omnivorous women.’ Golden et al (1982) concluded that ‘…that vegetarian women have an increased fecal output, which leads to increased fecal excretion of estrogen and a decreased plasma concentration of estrogen.’

Fiber may also be beneficial in the management of colorectal cancer, which is on the rise in younger women and men. A recent report by the World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research found that eating 90 grams of fiber-rich whole grains daily could lower colorectal cancer risk by 17 percent…and the side effects? A happier healthy digestive system, improved cardiovascular health and a lower risk of Type 2 Diabetes.

Your mother was right – eat your vegetables!

For more information on colorectal function and dysfunction, take Pelvic Floor Level 2A or for a deeper dive on the role of nutrition and pelvic health, why not take Megan Pribyl’s excellent course, Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist? Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient is also an excellent opportunity to learn about chemotherapy, radiation and pharmaceutical side effects of breast cancer treatment, as well as expected outcomes in order for the therapist to determine appropriate therapeutic parameters.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/fiber-has-surprising-anti-aging-benefits-but-most-people-dont-eat-enough-of-it/2018/04/27/c5ffd8c0-4706-11e8-827e-190efaf1f1ee_story.html?fbclid=IwAR0b-9VFUOCyUOgwe2BqV7-ahqwGzWs9rNpd1mscT75KNOGqnHm4ooFAu74&utm_term=.4d2784974ddc

Estrogen excretion patterns and plasma levels in vegetarian and omnivorous women. Goldin BR, Adlercreutz H, Gorbach SL, Warram JH, Dwyer JT, Swenson L, Woods MN. N Engl J Med. 1982 Dec 16;307(25):1542-7.

Diets and hormonal levels in postmenopausal women with or without breast cancer. Aubertin-Leheudre M1, Hämäläinen E, Adlercreutz H. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(4):514-24. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.538487.

Summer can make women cringe at the thought of baring most of their bodies yet finding just the right coverage for their breasts. Some scrounge for padded tops to pump up their actual A cup. Some seek the greatest amount of coverage to support every ounce of skin. And still others search for flattering tops to accentuate cleavage and minimize tan lines. Just like one swimsuit does not fit every woman, only one aspect of post-breast cancer rehab is not generally sufficient. A combination of exercise, mindfulness, and myofascial release may need to be implemented for optimal recovery.

Ibrahim et al., (2017) produced a pilot randomized controlled trial considering the effects of specific exercise on upper limb function and ability to return to work after radiotherapy for breast oncology. The study involved 59 young women divided into an exercise group or a control group that received standard care. The Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH), the Metabolic Equivalent of Task-hours per week (MET-hours/week), and a post hoc questionnaire on return to work were all used and recorded over 6 time periods after the 12-week post-radiation targeted exercise program. Women who had a total mastectomy still had upper limb dysfunction, but no there was no statistically significant difference in DASH scores between groups. Both groups at 18 months had returned to their pre-illness activity levels, and 86% returned to work (at just 8.5 fewer hours/week). The authors concluded exercise alone does not change the long-term outcome of upper limb function post-radiation.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for persistent pain in women after treatment for primary breast cancer was explored by Johannsen et al., in two 2017 articles, one concerned with clinical and psychological mediators and the other focused on cost-effectiveness. Each study included 129 women with persistent pain from breast cancer, placed in a MBCT group or a wait-list control group. The first study showed attachment avoidance was a statistically significant moderator, with subjects who had a higher attachment avoidance having lower pain intensity after MBCT. In the subjects undergoing radiotherapy, MBCT had a smaller effect on pain than those not having radiotherapy. The authors’ next study focused on the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) on pain intensity. Baseline and 6 months post-treatment data on healthcare utilization and pain medication were analyzed from national registries. The average total cost of the MBCT group was 730 euros less than the control group, and more women in the MBCT group had a MCID in pain than those in the control group.

DeGroef et al., (2017) performed a randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of myofascial techniques for breast cancer survivors who experienced upper limb dysfunctions. Fifty women post-unilateral breast cancer received either 12 sessions of standard physical therapy with myofascial therapy or 12 sessions of standard physical therapy plus a sham intervention during a 3-month period. After intervention, no significant differences between groups were found for active shoulder range of motion, lymphedema, handheld dynamometer strength, scapular statics and dynamics, shoulder function, or quality of life. The authors concluded shoulder ROM and function in both groups showed positive effects up to 1 year follow-up, but myofascial therapy provided no additional benefit in breast cancer patients.

Treatment for any patient should be individualized, based on deficits found clinically, whether they are physiological, anatomical, or psychological. Having a beach bag overflowing with techniques and tools, each ready to be used when the appropriate time comes, makes for a more competent therapist and a better rehabilitation outcome for patients. There simply is no “one size fits all” in breast oncology rehab.

YOU can be a major contributor to a breast cancer patients medical care team. Learn new skills by attending Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient this September in Boston, MA.

Ibrahim, M, Muanza, T, Smirnow, N, Sateren, W, Fournier, B, Kavan, P, Palumbo, M, Dalfen, R, Dalzell, MA. (2017). Time course of upper limb function and return-to-work post-radiotherapy in young adults with breast cancer: a pilot randomized control trial on effects of targeted exercise program. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: research and practice. http://doi:10.1007/s11764-017-0617-0

Johannsen, M, O'Toole, MS, O'Connor, M, Jensen, AB, Zachariae, R. (2017). Clinical and psychological moderators of the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer - explorative analyses from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncology. 56(2):321-328. http://doi:10.1080/0284186X.2016.1268713

Johannsen, M, Sørensen, J, O'Connor, M, Jensen, AB, Zachariae, R. (2017). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is cost-effective compared to a wait-list control for persistent pain in women treated for primary breast cancer-Results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. http://doi:10.1002/pon.4450

De Groef,A, Van Kampen, M, Verlvoesem N, Dieltjens, E, Vos, L, De Vrieze, T, Christiaen, MR, Neven, P, Geraerts, I, Devoogdt, N. (2017). Effect of myofascial techniques for treatment of upper limb dysfunctions in breast cancer survivors: randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 25(7):2119-2127. http://doi:10.1007/s00520-017-3616-9

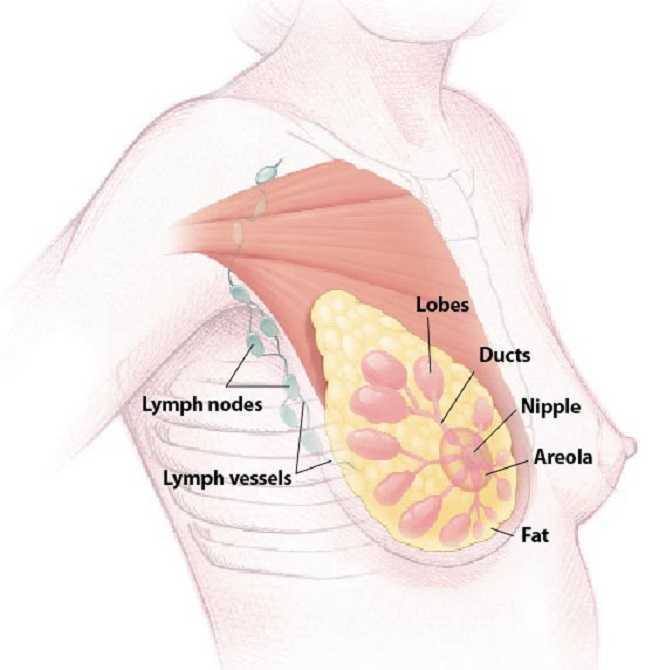

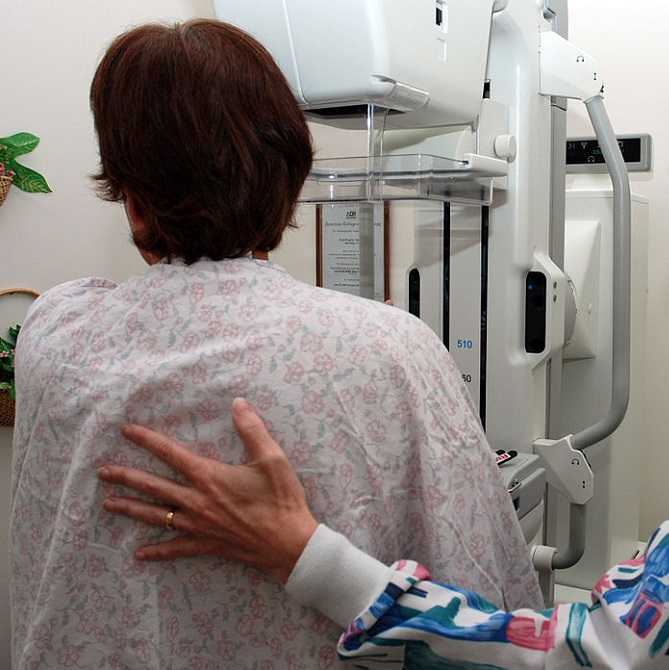

A diagnosis of breast cancer means many different things to many different people. Regardless, receiving this diagnosis means some sort of treatment will likely follow. The types of treatment and outcomes are largely dependent on individual patient scenarios, however, one thing is for certain: A patient’s life will be forever changed after having received this diagnosis.

Historically, comprehensive care for a patient with breast cancer has focused on treatment and prevention. However, more and more women are surviving breast cancer every year. Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to survivorship. Once someone has survived cancer, comprehensive, quality care should obviously focus on preventing recurrence, however, it may also include guidance and counseling on maintaining a healthy lifestyle and addressing physical and psychosocial changes.

A very recent 2016 article published in the Annals of Surgical Oncology discusses the subject of survivorship in breast cancer patients. This article suggests that the key to achieving successful outcomes for management of a breast cancer survivor is a multidisciplinary approach to help these survivors deal with the physical and psychosocial sequela resulting from their diagnosis.

A very recent 2016 article published in the Annals of Surgical Oncology discusses the subject of survivorship in breast cancer patients. This article suggests that the key to achieving successful outcomes for management of a breast cancer survivor is a multidisciplinary approach to help these survivors deal with the physical and psychosocial sequela resulting from their diagnosis.

As a pelvic rehabilitation provider, this is a very thought-provoking article as it outlines several areas in which I feel breast cancer survivors could benefit from physical therapy. A pelvic rehabilitation provider can be a valuable part of the multidisciplinary team that helps manage a breast cancer survivor towards positive and meaningful outcomes, ultimately enhancing their quality of life. The following are some areas addressed in the article in which a breast cancer survivor may need assistance to improve and support a meaningful quality of life.

Sexuality: According to this article, studies show treatment for breast cancer is associated with significant decrease in sexual interest, desire, arousal, and difficulty achieving orgasm and/or lack of sexual pleasure. Additionally, patients can also report pain with intercourse (dyspareunia) and/or vaginal dryness, which can lead to sexual dysfunction. Physical therapy can help by providing education on normal sexual response and lubricants, as well as help with tissue healing. Therapeutic techniques include exercise and manual treatments to areas that may be damaged from surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Additionally, exercise has been shown to improve self-image. Poor body image has been linked to sexual dysfunction following breast surgery (depending on the type “breast sparing techniques” versus mastectomy). This includes only some of the ways a physical therapist can help improve sexual dysfunction.

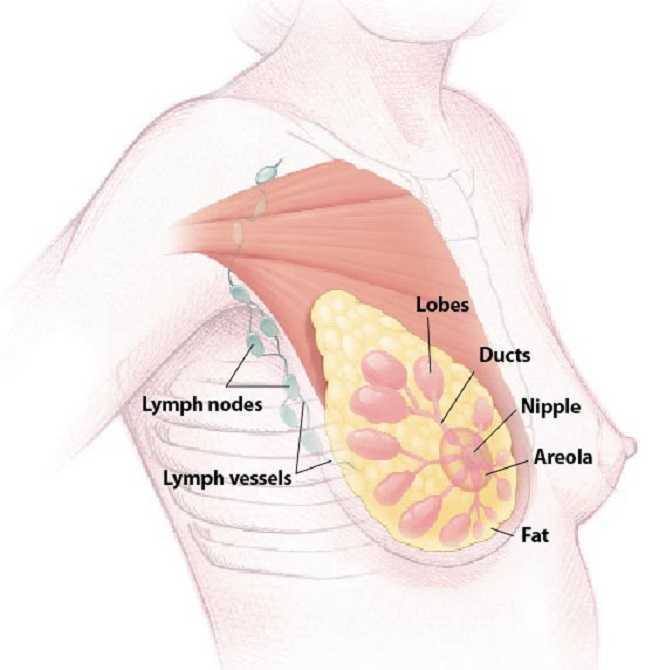

Lymphedema: According to the article, 30-70% of breast cancer patients experience lymphedema after treatment. Physical therapy can play an important role in the control and/or reduction of lymphedema. A physical therapist can provide helpful education, exercise, weight control, and, if needed, manual techniques and compression garments and bandaging.

Teachable moments after cancer diagnosis: A teachable moment is when you identify and seize an opportunity to educate your patient. After a life altering event or illness, people are more accepting of advice and change of lifestyle. As healthcare providers, we can utilize this time to help our patients improve outcomes by modifying their behavior. The cited article states there is clear evidence that physical activity decreases incidence and recurrence.There is additional evidence to show controlling weight and maintaining a normal body mass index (BMI) improves breast cancer survivor outcomes. A physical therapist can help a breast cancer survivor to develop a guided and progressive home exercise program to help them maintain normal BMI and participate in regular physical activity safely and regularly.

The discussed article, “Breast Cancer Survivorship: Why, What and When?”, sheds light on many areas of physical and psychosocial challenges that patients surviving breast cancer may deal with. This article also advocates that a multidisciplinary approach yields the greatest outcomes. I suggest that physical therapy can be a valuable part of the team when creating patient care plans for breast cancer survivors.

To learn more about breast cancer and outcomes based treatments, consider attending "Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient! The next course is taking place in Stockton, CA this September 24-25.

Gass, J., Dupree, B., Pruthi, S., Radford, D., Wapnir, I., Antoszewska, R., ... & Johnson, N. (2016). Breast Cancer Survivorship: Why, What and When?. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 1-6.

Susannah Haarmann, PT, CLT, WCS is the author and instructor of Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient. Join her this September 24-25 in Stockton, CA to learn about the various diagnostic tests, medical and surgical interventions to provide appropriate and optimal therapeutic interventions for breast cancer patients.

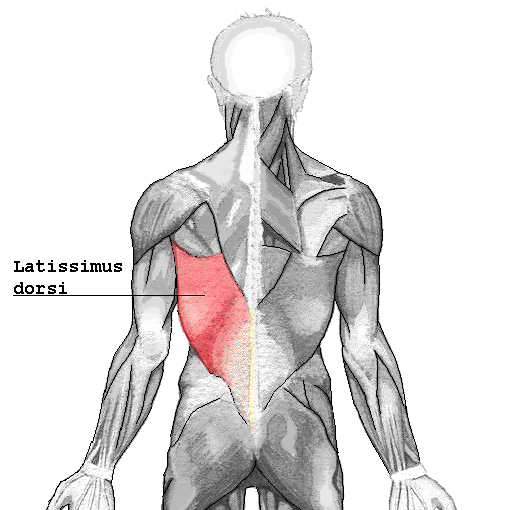

I turned to the literature and found prominent articles discussing breast reconstruction and giving minimal consequence to shoulder function after resection of the latissimus dorsi muscle. As a physical therapist, this left me in a quandary, “Really? Harvesting a portion of the broadest muscle of the back then threading it through the axilla to recreate the breast mound won’t have an impact on shoulder function or back pain? Impressive!” However, this did not correlate with my clinical findings. Often, scapulohumeral rhythm was altered, range of motion restricted and activities limited due to pain and fatigue. Scrutinizing the literature, I found that those articles were mostly unsubstantiated. Here is a quick summary of two systematic reviews published in 2014 addressing what the research really found pertaining to shoulder function after ‘lat flap’ reconstruction:

I turned to the literature and found prominent articles discussing breast reconstruction and giving minimal consequence to shoulder function after resection of the latissimus dorsi muscle. As a physical therapist, this left me in a quandary, “Really? Harvesting a portion of the broadest muscle of the back then threading it through the axilla to recreate the breast mound won’t have an impact on shoulder function or back pain? Impressive!” However, this did not correlate with my clinical findings. Often, scapulohumeral rhythm was altered, range of motion restricted and activities limited due to pain and fatigue. Scrutinizing the literature, I found that those articles were mostly unsubstantiated. Here is a quick summary of two systematic reviews published in 2014 addressing what the research really found pertaining to shoulder function after ‘lat flap’ reconstruction:

Patient impressions:

- Reported incidence of overall functional impairment is 41%. 8

- Overhead activities, lifting and pushing objects and high-level activities such as sport and housework were the most cumbersome. 1,7

- Subjective deficits did not resolve based on length of follow-up. 1

Strength:

- Greatest deficits are noted with reconstruction on the dominant side. 4

- Extension of the shoulder is the most common strength deficit followed by adduction then internal rotation. 8

- Objective strength deficits typically resolved within a year. 8,9

- Rehab should be ordered pro-actively. 4

Range of Motion:

- Active flexion is the most common restriction followed by abduction. 8

- Rarely were these restrictions severe. 5,6

- Restrictions were greatest post-operatively likely due to alterations in shoulder biomechanics, scar formation and post-operative pain.

- Discrepancies were found regarding resolution of range of motion without rehab. 5,8

- No clinically significant functional morbidity was found when therapy was provided from post-op day one. 2,3

Other reported complications that may impact function:

- Taratino, Banic and Fischer noted that capsular contracture was the most significant and recurrent complication in their study.10

- 50% reported post-operative numbness and tightness.1

- Scar tissue adhesions were associated with functional limitations.2,3

In conclusion, is it feasible to say that the latissimus dorsi muscle bears little consequence to function after reconstruction? I’m going to trust what the researchers performing the systematic reviews say:

- Physicians and researchers Lee and Mun state the following; “over 20 percent of the patients undergoing latissimus dorsi muscle transfer suffered from considerable disability…7% of patients changed their job postoperatively. These results suggest that considerable discomfort, even to the extent of limitation on daily activity, can be developed after latissimus dorsi muscle harvest, as opposed to the previous assumption that latissimus dorsi muscle harvest may not lead to serious disability” .8

- Smith does give merit to the fact that most strength deficits resolve within 6 to 12 months due to other muscles compensating for function, however, she states “standardization of physical therapy protocols is imperative as it appears to have a measurable positive impact.” Immediately after this statement she remarks that physical therapy is rarely included in the physician’s plan of care.9

I guess it is time we start talking to our surgical oncologists and plastic surgeons.

1. Adams, Jr., W., Lipschitz, A., Ansari, M., Kenkel, J., & Rohrich, R. J. (2004). Functional donor site morbidity following LD muscle flap transfer. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 53(1), 6–11.

2. de Oliveira, R., Nascimento, S., Derchain, S. & Sarian, L. (2013). Immediate breast reconstruction with a latissimus dorsi flap has no detrimental effects on shoulder motion or postsurgical complications up to 1 year after surgery. Plas¬tic and Reconstructive Surgery, 131(5), 673e–680e.

3. de Oliveira, R. R., Pinto e Silva, M. P., Costa Gurgel, M. S., Pas¬tori-Filho, L., & Sarian, L. O. (2010). Immediate breast re¬construction with transverse latissimus dorsi flap does not affect the short-term recovery of shoulder range of motion after mastectomy. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 64(4), 402– 408.

4. Forthomme, B., Heymans, O., Jacquemin, D., Klinkenberg, S., Hoff¬mann, S., Grandjean, F. X.,...Croisier, J. L. (2010). Shoulder function after latissimus dorsi transfer in breast reconstruc-tion. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, 30, 406– 412.

5. Giordano, S., Kääriäinen, M., Alavaikko, J., Kaistila, T. & Kuok¬kanen, H. (2011). Latissimus dorsi free flap harvesting may affect the shoulder joint in long run. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery, 100, 202–207.

6. Hamdi, M., Decorte, T., Demuynck, M., Defrene, B., Fredricks, A., VanMaele, G.,...Monstrey, S. (2008). Shoulder func¬tion after harvesting a thoracodorsal artery perforator flap. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 122(4), 1111–1117.

7. Koh, C. E., & Morrison, W. A. (2009). Functional impairment af¬ter latissimus dorsi flap. Australian Journal of Surgery, 79, 42–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04797.x

8. Lee, K.T., Mun, G.H., (2014).A systematic review of functional donor-site morbidity after latissimus dorsi muscle transfer, Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 134: 303.

9. Smith, S., (2014). Functional morbidity following latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction. J Adv Pract Oncol, 5, 181–187.

10. Tarantino, I., Banic, A., & Fischer, T. (2006). Evaluation of late results in breast reconstruction by latissimus dorsi flap and prosthesis implantation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 117(5), 1387–1394.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology convened their 2016 annual meeting over the weekend, and several of the presentations suggest new methods of preventing breast cancer recurrence.

Extended Hormone Therapy Reduces Recurrence of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer patients who are treated with aromatase inhibitor therapy are generally prescribed the the estrogen drugs for a five year course. A new study has suggested that by doubling the length of hormone therapy, the recurrence rate for breast cancer survivors drops by 34%. The study included 1,918 women who underwent five years of hormone therapy with the drug letrozole. After five years, half of the group switched to a placebo while the other half were given an additional five year treatment.

Breast cancer patients who are treated with aromatase inhibitor therapy are generally prescribed the the estrogen drugs for a five year course. A new study has suggested that by doubling the length of hormone therapy, the recurrence rate for breast cancer survivors drops by 34%. The study included 1,918 women who underwent five years of hormone therapy with the drug letrozole. After five years, half of the group switched to a placebo while the other half were given an additional five year treatment.

Drug Used to Treat Type 2 Diabetes May Increase Breast Cancer Survivability

The Univerisity of Pennsylvania School of Medicine has published results from two recent studies which document the effects of Metformin, a drug commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes, on breast cancer and endometrial hyperplasia. The study tracked outcomes for 1,215 patients who were diagnosed and surgically treated for breast cancer. Patients who began to use metformin after their diagnosis were found to have a 50% higher survivability rate than those who did not use metformin.

The timing of metformin use is extremely important when it comes to breast cancer survivability rates. The study also found that patients who used metformin prior to their diagnosis were more than twice as likely to die than those who never used the drug.

Research Suggests a "Mediterranian Diet" May Reduce Breast Cancer Recurrence

A study has indicated that a diet rich in vegetables, fish, and olive oil may decrease the odds of a breast cancer survivor experiencing a relapse or recurrence of their cancer. The study tracked 300 women with early-stage cancer and found that those who ate a normal diet were more likely to experience a breast cancer recurrence. The findings build upon previous research which indicated that a Mediterranean diet, and especially extra virgin olive oil, could reduce breast cancer risk by 68%.

Want to Learn More?

Susannah Haarmann, PT, CLT, WCS is the author and instructor of Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient, a course offered through the Herman & Wallace Institute. This continuing education course for medical practitioners offers a rehabilitation perspective for providers who work with oncology rehabilitation patients. Join Dr. Haarmann this in Stockton, CA on September 24-25 to learn evaluation and treatment techniques necessary to make an outpatient therapist an essential member of any oncology team.

1) Paul E. Goss, et al. J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl; abstr LBA1)

https://www.asco.org/about-asco/press-center/news-releases/ten-years-hormone-therapy-reduces-breast-cancer-recurrence

2) Yun Rose Li. University of Pennsylvania, American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting 2016

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2016-06/uops-ddm060316.php

3) http://www.scienceworldreport.com/articles/41404/20160606/mediterranean-diet-prevent-breast-cancer-recurring.htm

My first experience treating a patient with shoulder pain and limitations post-mastectomy just happened to be a local doctor’s sister. Luckily, I did not know this until a few sessions into her therapy. Ultimately, even more than normal, this patient’s outcome was a make or break situation for a future referral source. Her incredible spirit and optimism made the prognosis an inevitably positive one. Whether or not I had manual therapy training was a moot point, according to current research; however, from my perspective, I would not have been as competent in treating her without it.

In June 2015, De Groef et al. performed a review of literature to investigate the efficacy of physical therapy for upper extremity impairments after surgical intervention for breast cancer. Eighteen randomized controlled studies were chosen for review regarding the efficacy of passive mobilization, myofascial therapy, manual stretching, and/or exercise therapy after breast cancer treatment. In the studies reviewed, physical therapy began at least 6 weeks post-surgical intervention. Combining general exercise with stretching was confirmed effective on range of motion (ROM) by 2 studies. One study showed the effect of passive mobilization with massage was null for pain or impaired ROM. No study showed any effect of myofascial therapy, one poor quality study supported the use of passive mobilization alone, and one study showed no effect of stretching alone. Active exercises were found more effective than no therapy or simply education in five studies. Early intervention was found to be beneficial for shoulder ROM in 3 studies, but 4 other studies supported delayed exercise to promote wound healing longer. Ultimately, pain and impaired shoulder ROM after operative treatment for breast cancer have been treated effectively by a multifactorial approach of stretching and active exercise. The efficacy of passive mobilization, stretching, and myofascial therapy needs to be investigated with higher quality research in the future.

In June 2015, De Groef et al. performed a review of literature to investigate the efficacy of physical therapy for upper extremity impairments after surgical intervention for breast cancer. Eighteen randomized controlled studies were chosen for review regarding the efficacy of passive mobilization, myofascial therapy, manual stretching, and/or exercise therapy after breast cancer treatment. In the studies reviewed, physical therapy began at least 6 weeks post-surgical intervention. Combining general exercise with stretching was confirmed effective on range of motion (ROM) by 2 studies. One study showed the effect of passive mobilization with massage was null for pain or impaired ROM. No study showed any effect of myofascial therapy, one poor quality study supported the use of passive mobilization alone, and one study showed no effect of stretching alone. Active exercises were found more effective than no therapy or simply education in five studies. Early intervention was found to be beneficial for shoulder ROM in 3 studies, but 4 other studies supported delayed exercise to promote wound healing longer. Ultimately, pain and impaired shoulder ROM after operative treatment for breast cancer have been treated effectively by a multifactorial approach of stretching and active exercise. The efficacy of passive mobilization, stretching, and myofascial therapy needs to be investigated with higher quality research in the future.

Another review of literature in 2010 by McNeely et al. used 24 studies to analyze the effectiveness of exercise intervention for upper extremity impairments after breast cancer surgical intervention. Ten of the studies focused on early versus late intervention, and all supported the earlier implementation of post-surgical exercises for ROM; however, wound drain volume and duration were increased in the subjects engaged in earlier exercises. Fourteen studies showed structured exercise intervention improved shoulder ROM significantly in the post-op period, and a 6-month follow up continued to show improved upper extremity function. No lymphedema risk was noted in any of the studies.

As with many areas of physical therapy, better research is needed to support what we do. We often treat with success in the clinic despite lack of strength in the evidence-based realm. After implementing glenohumeral and scapulothoracic mobilizations, soft tissue work in the posterior cervical and scapular muscles (avoiding lymph nodes), stretching, progressive resisted strengthening, and a home program, my patient regained full range of motion and function of the affected shoulder after her mastectomy. In retrospect, I should have written up a case study on this patient to contribute to our profession. At least after my patient was discharged, the clinic where I worked received a healthy supply of future referrals from her sister because of the positive results achieved with therapy.

If you are interested in learning evaluation and treatment techniques which can benefit breast oncology patients, consider a Herman & Wallace Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient course in 2016.

De Groef A, Van Kampen M, Dieltjens E, Christiaens MR, Neven P, Geraerts I, Devoogdt N. (2015). Effectiveness of postoperative physical therapy for upper-limb impairments after breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 96(6):1140-53. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.01.006. Epub 2015 Jan 13.

McNeely ML, Campbell K, Ospina M, Rowe BH, Dabbs K, Klassen TP, Mackey J, Courneya K. (2010). Exercise interventions for upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. The Cochrane Database System of Reviews. (6):CD005211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005211.pub2.

Milk duct blockage is a common condition in breast feeding mother’s that can cause a multitude of problems including painful breasts, mastitis, breast abscess, decreased milk supply, breast feeding cessation, and poor confidence with decreased quality of life. A recent study in 2015 in The Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1, showed that physical therapy (PT) maybe a helpful treatment for the lactating mother experiencing milk duct blockage when conservative measures have failed. Common conservative measures typically recommended are self-massage, heat, and regular feedings. The World Health Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and Academy of Breast Feeding Medicine, all recommend breast feeding as the primary source for nutrition for infants. There are many benefits to both the mother, and the infant, when breast feeding is used as the primary source for nutrition in infants. Having blocked milk ducts make it difficult and painful to breast feed and can lead to poor confidence for the mother and a frustrated baby as the milk supply could be reduced or inadequate. The primary health concern for blocked milk ducts is mastitis. Mastitis is defined as an infection of breast tissue leading to pain, redness, swelling, and warmth, possibly fever and chills and can lead to early cessation of breast feeding.

A blocked milk duct is not a typical referral to PT, however, this study outlined a protocol used for 30 patients with one or more blocked milk ducts that were referred to PT by a qualified lactation consultant. This study was a prospective pre/posttest cohort study. As an outcome measure, this study utilized a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for 3 descriptive areas: pain, difficulty breast feeding, and confidence in independently nursing before and after treatment. The treatment protocol included moist heat, thermal ultrasound, specific manual therapy techniques, and patient education for treatment and prevention of the blockage(s). The thermal ultrasound and moist heating provided the recommend amount of heat to relax tissue around the blockage. Ultrasound also provided a mechanical effect that assists in the breaking up of the clog and increased pain threshold for the patient to improve tolerance to the manual clearing techniques. Next, the specific manual therapy was provided to directly unclog the blockage(s), and lastly the education provided was to help the patient identify and clear future blockages to prevent recurrence. 22 of the 30 patients were seen for 1-2 visits, 6 were seen for 3-4 visits, and none of the mother’s condition progressed to infective mastitis or developed breast abscess’s.

A blocked milk duct is not a typical referral to PT, however, this study outlined a protocol used for 30 patients with one or more blocked milk ducts that were referred to PT by a qualified lactation consultant. This study was a prospective pre/posttest cohort study. As an outcome measure, this study utilized a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for 3 descriptive areas: pain, difficulty breast feeding, and confidence in independently nursing before and after treatment. The treatment protocol included moist heat, thermal ultrasound, specific manual therapy techniques, and patient education for treatment and prevention of the blockage(s). The thermal ultrasound and moist heating provided the recommend amount of heat to relax tissue around the blockage. Ultrasound also provided a mechanical effect that assists in the breaking up of the clog and increased pain threshold for the patient to improve tolerance to the manual clearing techniques. Next, the specific manual therapy was provided to directly unclog the blockage(s), and lastly the education provided was to help the patient identify and clear future blockages to prevent recurrence. 22 of the 30 patients were seen for 1-2 visits, 6 were seen for 3-4 visits, and none of the mother’s condition progressed to infective mastitis or developed breast abscess’s.

The results of the study showed the protocol used was helpful to ease pain, reduce difficulty with breast feeding, and improve confidence with independent breast feeding for lactating women that participated in the study. Although treatment of blocked milk ducts in lactating mothers is not a common PT referral, this study shows that PT may be one more helpful treatment for a patient experiencing this problem that is not responding to traditional conservative treatment. Since breast feeding is important to both mother and infant and is the primary recommended source for infant nutrition, it is important that a lactating mother receives quick, effective treatment for blocked milk ducts to prevent onset of mastitis and breast abscess that lead to early cessation of breast feeding. The cited study recommends that women who suspect a blocked milk duct or are having problems with breast feeding always seek care from a certified lactation consultant first, and that PT may be a referral that is made.

Cooper, B. B., & Kowalsky, D. S. (2015). Physical Therapy Intervention for Treatment of Blocked Milk Ducts in Lactating Women. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 39(3), 115-126.

Today we hear more from Susannah Haarmann, PT, WCS, CLT about how pelvic rehabilitation practitioners are suited to contribute to a breast oncology patient's medical team. Susannah will be sharing more insights and treatment tools at the Rehabilitation for the Breast Cancer Patient course taking place June 27-28 in Maywood, IL.

Most pelvic rehab practitioners are incredible problem solvers and independent thinkers. We understand that often our referrals from a physician occur after a battery of tests and ineffective medical interventions. We may agree to treat a patient only to find that the diagnosis is vague and the patient often feels lost and broken. So we take out our sleuth caps, ask as many subjective questions as it takes and see where our objective examination leads us. Afterwards we paint a picture of our findings, focus the patient on what is working, tell them where we are going to start and how we are going to build one brick at a time.

The same is true for rehabilitation and breast oncology. Most physicians don’t understand how our work as therapists can complement and alleviate the side effects of mainstream medical intervention, but when the pain medication no longer works, we are there. When the range of motion no longer exists to get the patient’s arm into a cradle for breast radiation, we are there. And when the patient walks in our door, we are there, quite often for a period of time that extends well beyond after treatments cease, because the potential side effects of breast cancer, if they occur, may take years or even decades to show up. The rehab practitioner understands how to prepare the patient, without fear, for what the road ahead may look like. The purpose of this education is to empower patients to serve as their own best advocates. Pelvic practitioners and breast oncology specialists are noted for their exceptional manual skills. We are also versed to pounding the pavement educating physicians, patients and other therapists alike about who we can serve and how we can be of service. We are definitely a unique breed of therapists.

The Rehabilitation for the Breast Cancer Patient course will add to the pelvic rehab practitioner's current knowledge allowing them to become a specialist. Consider the following:

A therapist understands the biomechanics of a shoulder joint and function, but do they understand how the effects of radiation, reconstruction procedures and impairments in the lymphatic system as a side effect of cancer treatment might prevent optimal upper extremity function?

A therapist may understand peripheral neuropathy and balance training or osteoporosis and aging, however, do they understand which chemotherapeutic and hormone therapies may cause these side effects and how the prognosis may differ depending upon which medical intervention was used?

A therapist may commonly treat back pain, but do they understand how a plan of care might be altered to accommodate for a patient who experienced a TRAM flap or latissimus dorsi reconstruction?

A therapist may be able to initiate a post-operative rotator cuff strengthening program for the upper extremity, but if the patient has a history of lymphedema, how do these parameters change?

A therapist may have advanced manual therapy skills, but how might one use these skills to identify and treat lymphatic cording or set safe parameters for working around radiated tissue to restore optimal function?

These are just a few of many examples of what constitutes a specialist in the field of breast oncology and each of these questions and more will be covered in detail in the course Rehabilitation for the Breast Cancer Patient.

Today we hear from Susannah Haarmann, the instructor for Rehabilitation for the Breast Cancer Patient. If you want to learn how to implement your pelvic rehab training with breast oncology patients, join Susannah in Maywood, IL on June 27th and 28th.

Effective pelvic rehab practitioners demonstrate many skills which are especially suitable to treat people with breast cancer, however, the first idea that comes to mind is that they understand what my friend refers to as, ‘the bikini principle.’ She remarked this week that I treat the ‘no no’ areas; the private places that we rarely share…with anyone. The reproductive regions of the pelvis and chest wall both consciously and subconsciously are associated with a plethora of personal psychological and social connotations. A pelvic health practitioner has a raised level of sensitivity to working with this patient population; there is no true protocol in this line of work, effective treatment will require a deeper level of listening and being present with the patient, and a person’s healing of the pelvic region is likely to go beyond the physiologic realm.

The biopsychosocial model of treatment is especially pertinent to the pelvic and breast oncology specialties. The breasts have great biological importance for sexual reproduction and nurturing offspring. Psychologically, breasts represent femininity for many women (and imagine how the story would change for a male with breast cancer.) Furthermore, different societies tend to create a host of rules and guidelines about what is ‘breast appropriate.’ The rehab practitioner understands that a person’s perceptions of their breasts are unlike any others and the same holds true for their cancer journey and goals with therapy.

The pelvic practitioner understands the importance of a straight face; if you have been in the field long enough something completely surprising is bound to occur, but in the day in the life of a pelvic rehab practitioner, no matter how shocking, we’ve seen it before, right? The breast oncology practitioner is going to visualize radiation burns that make their own chest wall hurt upon seeing it. Practitioners will encounter the most frustrating of severe functional deficits that could have been easily avoided had there been the opportunity for earlier intervention. The rehab practitioner providing breast oncologic care understands the story is complex, the road may be long, and although our role revolves around the body, the side effects of our treatment may have much greater reward beyond just physical function.