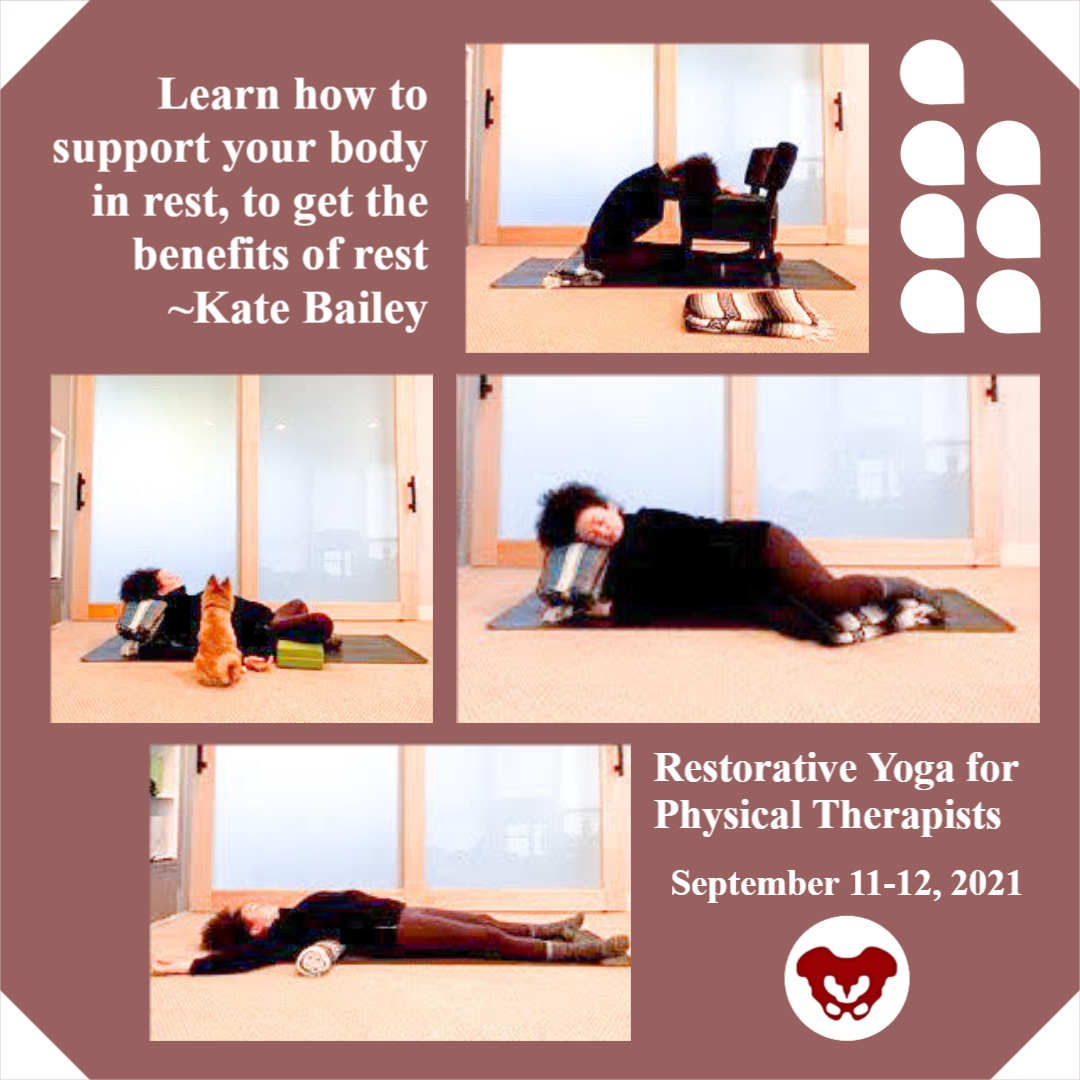

Kate Bailey, PT, DPT, MS, E-RYT 500, YACEP, Y4C, CPI curated and instructs the remote course on Restorative Yoga for Physical Therapists, which is scheduled for September 11-12, 2021. Kate brings over 15 years of teaching movement experience to her physical therapy practice with specialties in Pilates and yoga with a focus on alignment and embodiment. Kate’s pilates background was unusual as it followed a multi-lineage price apprenticeship model that included the study of complementary movement methodologies such as the Franklin Method, Feldenkrais, and Gyrotonics®. Building on her Pilates teaching experience, Kate began an in-depth study of yoga, training with renown teachers of the vinyasa and Iyengar traditions. She held a private practice teaching movement prior to transitioning into physical therapy and relocating to Seattle.

Without a doubt, these past couple of years have been tough with this global pandemic of a virus that caused major shifts in how we work, play, learn and socialize. Wherever you live on this planet, it is nearly impossible not to have been affected by the stress and trauma that the Covid-19 virus has created. Just like with any other stressor, the first step of management is recognition. Check, done.

Step two involves making conscious choices about how we want to live. This is where we have some options, including self-care. “Self-care” is one of my least favorite phrases. Not because at its core, self-care is not important. But because it's another thing on an overflowing to-do list and can create even more of a sense of imbalance, lack of accomplishment, and self-defeat. Yet, learning how to manage stress is a skill we all need: individually and communally.

However, there is a step before stress management that we need to address first. Interoception, defined by Porges, Ph.D., is the process that describes both conscious feelings and unconscious monitoring of bodily processes by the nervous system. As a clinician, this is a key aspect of every single patient care plan. I am a big fan of embodied decision making, and yet our somatic intelligence (or interoceptive skills) is widely underdeveloped.

Just as emotional intelligence is getting some wonderful development, through the work of researchers and educators like Marc Brackett, Ph.D. of Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, our wellbeing and access to wellness are dependent on our ability to understand the sensations and signals throughout our body and then make a choice. This is important since you can’t make an embodied choice (step 2) before you have the data (step 1 - interoception). An example would be to imagine if you never felt the sensation of hunger, or the ‘hangry’ feeling when it’s been too long since the last boost of nourishment…how would you determine that you are hungry?

So, what to do? Many of us (clinicians and patients alike) live in a world full of overstimulation, productivity requirements, and constant stress. To develop interoception, finding little periods of stillness can be really useful. In yoga, there is a dedicated practice called pratyahara. Translated from Sanskrit to English as ‘withdrawal of the senses.’ The senses, in this case, includes all the sense organs: sight, smell, sound, touch, taste, movement (vestibular), and spatial placement (proprioception). Traditionally this is an aspect of meditation.

In my experience as a yoga teacher and physical therapist, I find this practice more accessible in the restorative yoga practice. It can take some graded exposure, but at the heart of the restorative yoga practice is stillness, darkness, silence, and support from props so that the body doesn’t have to do anything. These are also the essential components described by Herbert Benson, MD in his work on the Relaxation Response. In his work, he showed the relaxation response to be effective in decreasing heart and respiration rate triggering the benefits of the vagal nerve; which we are learning has so much to do with our ability to neuroregulate and participate in individual and communal stress management.

Restorative yoga is a practice of wakefully resting. Immordino-Yang et al, studied the brain in functional MRI when individuals were wakefully resting. The study found that during wakeful rest (without a meditative component where the brain has a task of concentration) the brain goes into a mode of neural processing called default mode. In default mode, the brain supports memory recall, imagining the future, and developing socio-emotional intelligence. In relationship to stress management, this is so important because it re-centers us, and allows for connection for even more neuroregulation.

For my patients, I often joke about lying on the floor. Really, it is not a joke at all. Lying on the floor for 15 minutes is savasana. Savasana is a wakeful resting and a practice of relaxation response. It seems easy: you always have access to a floor. You don’t need anything fancy. Aside from the neuroregulatory benefits of rest, savasana also gives the postural muscles a break. It allows the hip flexors to re-lengthen and the cervicothoracic junction to realign.

It is pretty great, and really accessible for most people. For those who are not comfortable flat, that’s where the props used in restorative yoga come into play. As physical and occupational therapists, we are so well primed to help people learn how to support their bodies in rest to get the benefits of rest.

Burnout, the Secret to unlocking the stress cycle by Emily Nagoski, Ph.D. and Amelia Nagoski, DMA

Polyvagal Theory, Stephen W Porges, PhD

Immordino-Yang et al. - Perspectives on Psychological Science - 2012

The Relaxation Response by Herbert Benson, MD, and Miriam Z Klipper

Mia Fine, MS, LMFT, CST, CIIP is the author and instructor of the Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists remote course scheduled for August 14-15, 2021. Mia’s specialties are sexual health concerns, eroticism, intimacy, alternative sex and relationships (kink/BDSM and non-monogamy), LGBTQIA+ genders/orientations/sexualities, and desire discrepancy. Her course Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists is intended for pelvic rehab therapists who want to learn tools and strategies from a sex therapist’s toolkit. Mia shares the following blog detailing some of the books that have influenced her.

As a science, psychology, somatics, and sexuality education nerd, books are my go-to psychoeducation sources. The books listed below are resources that I offer to my clients, send to family and friends for birthdays and holidays, and inform the work I do as a clinical supervisor, professor, and therapist. I’m excited to share some of my favorites that might help you and the patients with whom you work.

A prerequisite for anyone with a vulva (or who is partnered with someone with a vulva) is the book Come As You Are written by Emily Nagoski. Before a therapeutic intake session, I invite my clients who have vulvas to read this book. It is important to me that my clients and I share the same language that is offered in this fabulous resource. Nagoski illustrates the Dual Control Model for sexual arousal, interest, and desire in ways that are accessible and digestible for all. When clients understand the difference between Spontaneous Arousal and Responsive Arousal, and why these happen, and when, it is a game-changer for them and their partner. This book is a must for anyone who works with pelvic floor pain. And excitingly, these topics will be covered in my upcoming Herman & Wallace course!

The Politics of Trauma written by Staci Haines (also the author of Healing Sex) is a deep dive into, well, the politics of trauma. In this book, she explores the somatic experiences we humans have when we are activated. Her detailed description of fight, flight, freeze, fawn, and dissociate is nothing short of brilliant. This book is a must for those who are interested in exploring the impact that social justice, racial justice, transformative justice, and restorative justice have on our lived experiences of trauma.

The Body is Not An Apology is another brilliant book by Sonya Renee Taylor. It highlights the many effects of the “isms and obias” (such as Sexism, Racism, Fat-phobia, Transphobia) embedded in our everyday life and how identifying these frees us of the barriers they place on our quality of life. The isms and obias she explores impact the way we view ourselves, talk to ourselves, and relate to others. This book is incredibly inspiring, as is the author, Sonya Renee Taylor.

Additional books I love, many of which are written by close friends and colleagues include:

- Trans Sex by Lucie Fielding

- Wild Side Sex: the Book of Kink by Midori

- Gender Trauma by Alex Iantaffi

- Polyvagal Exercises for Safety and Connection by Deb Dana

- Becoming Cliterate by Laurie Mintz

- Better Sex Through Mindfulness by Lori A. Brotto

- The Art of Giving and Receiving: The Wheel of Consentby Betty Martin, Robyn Dalzen

These books have improved, and informed, my therapeutic work with clients and are recommendations I offer on a weekly, if not daily, basis. For additional resources, check out my website:https://miafinetherapy.com/. I look forward to exploring more comprehensive and accessible resources with you at my upcoming course Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists remote course scheduled for August 14-15, 2021!

The majority of practitioners begin their pelvic rehabilitation journey by taking Pelvic Floor Level 1, which is an excellent starting point. This course provides the basics of anatomy, techniques, and knowledge needed to start treating patients.

Another option for your pelvic floor journey is the Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Level 1 remote course. Caring for patients with cancer begins at diagnosis, and as a pelvic rehabilitation practitioner, you are an integral part of the oncology team. This course addresses the issues commonly seen in a patient who has been diagnosed with cancer.

Several cancers can affect the pelvic region and pelvic floor. Such cancers include bladder, colorectal, prostate, and ovarian cancers. Treatments for pelvic cancers include surgery, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and pelvic rehabilitation. These treatment options depend on the tumor size, location, or stage and negatively affect pelvic floor function and quality of life.

Cancer patients also often have intimacy issues that stem from their diagnosis and treatment. Holly Tanner shares that "...cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work-life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels. Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido, and performance anxiety can create further challenges." A pelvic rehabilitation practitioner can assist the patient in their recovery and reframing of intimacy.

In addition to sexual function, the pelvic floor helps to maintain bladder/bowel control (emptying, urges), organ support, and stabilization of the spine/pelvis. Pelvic issues that originate from cancer treatment vary from scar tissue restriction or swelling, fibrosis causing narrowing and hardening of tissues, sexual issues, and lymphedema, among other issues. While some patients may not display symptoms at all, others can develop issues immediately after treatment, or even months after treatment has ended.

There are over 15 million cancer survivors in the United States. In the next 10 years, this number will increase to over 20 million. The need for trained practitioners to treat patients with cancer diagnoses will only be increasing in the future. Join H&W on August 15-16 in Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Level 1 and learn to be part of an interdisciplinary oncology team.

How do healthcare practitioners improve patient satisfaction? Patient satisfaction is a cognitive evaluation of an emotional reaction to their health-care experience. According to multiple studies, the most significant predictor of patient satisfaction is the quality of their conversations with their medical practitioners.

Patients care about:

- Being listened to

- Being treated courteously and respectfully

- Being involved in decisions about their healthcare

- Receiving clear explanations about their medical status and treatment

This is good news because they are all factors that you can control. Practitioners who take the time to communicate clearly, listen intently, understand each patient as an individual, and respond compassionately can improve their patients’ satisfaction and treatment outcomes. As Lauren Mansell stated in an interview with H&W, you have to “know what questions to ask patients for treatment. Our patients often feel alone, are frustrated with medical treatments, and feel like no one can address their symptoms.”

When patients are facing a difficult or new medical situation, they are in a threat state. This means that emotions get triggered, the limbic system gets activated, and the prefrontal cortex starts to deactivate. This results in patients who are not thinking clearly, listening well, or who appreciate a different mindset.

Herman & Wallace offers courses on treating the pelvic floor, and also the whole patient. Strengthen your clinical interactions with one of their courses:

- Sexual Interviewing for Pelvic Health Therapists – with Mia Fine, MS, LMFT, CST, CIIP

- Trauma Awareness for the Pelvic Therapist – with Lauren Mansell DPT, CLT, PRPC

- Inclusive Care for Gender and Sexual Minorities – with Brianna Durand, PT, DPT

One of the most important things that a practitioner can learn is to never assume that you know how your patient feels or identifies. No two people are the same. Faculty member, Brianna Durand shares that “Ultimately, the best method to providing compassionate and competent care is to minimize your assumptions.” Brianna shares this example in a recent interview, “if you find yourself assuming someone’s gender identity based on their name or appearance, I’d challenge you to practice using the gender-neutral they/them pronoun until you learn how they identify. If you are unsure, it is okay to privately ask them!”

Faculty member, Mia Fine further stresses that “It is important that providers be aware of their own biases and be introduced to the various sexual health resources available to providers and patients.” Listen to your patient to understand what they are saying and feeling. Do not respond defensively. Remember that this can feel like a threatening situation for patients.

Happy patients are more likely to return to your practice in the future, recommend your practice to their friends, and pay their bills on time and in full. Patients want to have quality interactions with a healthcare provider who cares about them. As a practitioner, your satisfied patient is more likely to make follow-up appointments and maintain their prescribed treatment plan, which can lead to more positive outcomes.

The following is our interview with Jennifer Eller, PT, DPT, PRPC. Jenni recently passed the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification (PRPC) exam. She practices at Enloe Medical Center in Chico, CA and is a Teaching Assistant for local California satellite courses with H&W. Jenni was kind enough to share some thoughts about her career with us. Thank you, Jenni - and congratulations on receiving your PRPC!

Q: Who are you? Describe your clinical practice.

A: My name is Jenni Eller, and I am a pelvic floor physical therapist at Enloe Rehabilitation Center (hospital-based outpatient clinic) in Chico, CA. I specialize in pelvic floor, orthopedic, and oncological diagnoses. Specifically, conditions related to incontinence, pelvic pain, dyspareunia, vaginismus, interstitial cystitis, and the post-surgical pelvis, as well as pelvic floor issues, post-oncological treatment pelvic floor issues, pre and postnatal issues, male pelvic floor dysfunction, and other pelvic floor dysfunctions.

Q: How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field, and what has your educational journey as a pelvic rehab therapist looked like?

A: I grew up in Oregon and Washington, and completed my undergraduate degree in Exercise Science at Linfield College in 2009. I completed my Doctorate Degree in Physical Therapy at Regis University in Denver, CO in 2013.

After graduate school, I worked in a small rehabilitation hospital but quickly transitioned to outpatient rehabilitation and started working with the orthopedic and oncological patient population. The hospital system I was in had hired 3 new gynecology oncologists and were interested in developing the pelvic health program there. I started my training for pelvic floor physical therapy with Herman and Wallace in 2015. I have completed the Herman and Wallace Pelvic Floor series in 2017 and passed the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification in May 2021.

Q: What patient population do you find most rewarding in treating and why?

A: Over the past 6 years, I have enjoyed helping both women and men with issues related to their pelvic floor, connecting it to their spine, hip, abdominal, and lower extremity issues. I help them return to an active lifestyle and feel empowered over something so limiting and invisible to others.

Patients with pelvic floor dysfunction are often overlooked because their symptoms are too sensitive to speak about. I truly believe they deserve the best care possible and am grateful to be part of a team that focuses on patient-centered care. Treating both pelvic floor dysfunction and the oncological patient population benefits under-served patient populations. Both demographics have my heart for personal reasons. I always knew I wanted to help those who are in need able to get much support.

Q: What has been your favorite Herman & Wallace Course and why?

A: I have enjoyed the whole pelvic floor series, but Pelvic Floor Level 1 and Level 2B, taught by Tina Allen and Holly Tanner, were so great! These courses just inspired me to give my full attention to pelvic health. They are easy to learn from and full of so much knowledge.

Q: What is in store for you in the future as a clinician?

A: Right now, I am focused on building the pelvic health program in this smaller northern California city and hopefully bringing more providers to serve this community. I have a dream of teaching in the future and helping build the next generation of physical therapists and pelvic floor physical therapists.

Portions of this blog are from an interview with Dustienne Miller. Dustienne is the creator of the two-day course Yoga for Pelvic Pain. She passionately believes in the integration of physical therapy and yoga in a holistic model of care, helping individuals navigate through pelvic pain and incontinence to live a healthy and pain-free life.

Have you noticed when you are afraid or don’t want to feel something you hold your breath? Imagine what it's like to have daily pain that limits function and how that could impact rib cage, abdominal and pelvic floor expansion. Dustienne Miller discusses this in her remote course, Yoga for Pelvic Pain, upcoming on July 31 - August 1, 2021. Her course focuses on two of the eight limbs of Patanjali’s eightfold path: pranayama (breathing) and asana (postures) and how they can be applied for patients who have hip, back, and pelvic pain.

Dustienne explains "We teach our patients how breathing patterns inform our digestion, our spine, our emotional state, our pelvic floor, etc. It’s one of the most powerful tools we have to inform our system that we are safe. Despite this knowledge, we will often find ourselves holding our breath or breathing in non-optimal ways without even realizing it." Dustienne focuses her practice on introducing yoga to patients within the medical model. Yoga can be included in pelvic rehabilitation in so many ways, including incorporating yoga home programs as therapeutic exercise and neuromuscular re-education (both between visits and after discharge).

Pelvic conditions that can be positively impacted by yoga are interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, vulvar pain, coccydynia, hip pain, and pudendal neuralgia. Treatment for these conditions often involves an individualized approach that may include both pharmacologic therapies (prescription drugs, analgesics, and NSAIDs) and nonpharmacologic interventions such as exercise, muscle strength training, cognitive behavioral therapy, movement/body awareness practices, massage, acupuncture, and nutrition.

A systematic review of the 2017 clinical practice guidelines evaluated 14 randomized controlled trials and found that yoga was associated with lower pain scores (1). Similarly, in 2020 there was a review of 25 randomized controlled trials that examined the effects of yoga on back pain. Out of these trials, 20 studies reported positive outcomes in pain, psychological distress, and energy (2).

The great thing about yoga is that the asanas (postures) can be modified to accommodate your strength, experience, and health conditions. An example of this is the Downward Facing Dog pose. There are so many ways to made Downward Facing Dog work for your body. Use straps, the wall, or the plinth/countertop to provide support for your body as needed, which might look different each day.

Some folks think you need to be flexible to have a yoga practice. Dustienne stresses "What is necessary is to be flexible with understanding that every day might feel different. If you are in an active pain flare your practice will look different than on the days you are feeling better. That can be a challenging aspect of a mindful practice - embracing that every day is different. Have the courage not to judge yourself, but to celebrate that you are meeting your needs with kindness."

People have been doing yoga for thousands of years. It is a mind-body and exercise practice that combines breath control, meditation, and movements to stretch and strengthen muscles. Join Dustienne Miller in Yoga for Pelvic Pain on July 31 - August 1, 2021, to learn more about incorporating yoga into your clinical practice.

No prior experience with teaching yoga is required to attend the course. However, all participants must possess a working knowledge of pelvic pain conditions and foundational rehabilitation principles.

- Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017; 166(7):493-505.

- Park J, Krause-Parello CA, Barnes CM. A narrative review of movement-based mind-body interventions: effects of yoga, tai chi, and qigong for back pain patients. Holist Nurs Pract. 2020;34(1):3-23.

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC has attended extensive post-graduate rehabilitation education in the area of Parkinson disease and exercise. She is certified in LSVT (Lee Silverman Voice Treatment) BIG and is a trained PWR! (Parkinson Wellness Recovery) provider, both focusing on intensive, amplitude, and neuroplasticity-based exercise programs for people with Parkinson disease. Erica has taken a special interest in the unique pelvic floor, bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues experienced by individuals diagnosed with Parkinson disease. You can learn more about this topic in Erica's course, Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation, scheduled for July 23-24, 2021.

Parkinson disease (PD) non-motor symptoms can be even more impactful on quality of life than the cardinal motor symptoms most are familiar with, bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, and postural instability. The list of non-motor symptoms is extensive affecting many body systems including cognitive, sensory, and autonomic.

Constipation is one of the most common autonomic non-motor symptoms experienced by people with Parkinson disease with studies showing 20-89% prevalence (1). As the disease progresses, individuals are more likely to experience symptoms that suggest a strong relationship between neurodegeneration and bowel dysfunction, such as, decreased frequency of bowel movements, difficulty expelling stool, and diarrhea (2). Constipation has also been hypothesized to be an early indicator for the development of Parkinson disease, and there is ongoing research in this area. It has yet to be shown that constipation is specific enough to predict the development of PD.

Developing an understanding of Parkinson disease constipation and how it differs from other individuals with constipation can have a strong impact on our recommended pelvic rehabilitation plans of care. In a study published by Zhang, M. et al., 2021, they looked at the characteristics of Parkinson disease with constipation (PDC) compared to functional constipation (FC). Functional constipation is generally defined as difficult, infrequent, or incomplete defecations (3). One of the main findings in this study was a significant difference between the groups when looking at resting rectal and anal canal pressures. In the PDC group, resting rectal and anal pressures were significantly lower. These resting pressures are mainly controlled by the internal anal sphincter resting tension which is supported by the autonomic nervous system. This leads the researchers to speculate there may be autonomic nervous system neuropathy in people with PD

They then looked at simulated defecation, which also showed that the PDC group had significantly lower rectal defecation pressure and a lower anal relaxation rate. Since rectal pressures during defecation assist in effective anal relaxation, the researchers state, “a coordinated movement disorder results” and that people with PD may have “pelvic floor cooperative motion disorder” (1). Additionally, the researchers noted that abnormal abdominal pressure is another main contributing factor to the low rectal defecatory pressure in PDC. Abdominal pressure is a key factor in driving complete and efficient rectal defecation. This is also a finding in numerous other studies in the literature unique in PDC.

The results of Zhang, M. et al., 2021 reveal the need for pelvic health practitioners to help train coordinated defecation efforts in people with Parkinson disease. In my course, Parkinson disease and Pelvic Rehab, we will have an in-depth discussion about how training defecatory dynamics is different in people with PD. Muscle training principles in this population are very unique. Understanding the underlying causal factors of dysfunction will have a significant impact when helping patients with Parkinson disease manage constipation.

- Zhang, M., Yang, S., Li, X. C., Zhu, H. M., Peng, D., Li, B. Y., ... & Tian, C. (2021). Study on the characteristics of intestinal motility of constipation in patients with Parkinson's disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 27(11), 1055.

- Sakakibara, R. (2021). Gastrointestinal dysfunction in movement disorders. Neurological Sciences, 1-11.

- Lacy, B. E., Mearin, F., Chang, L., Chey, W. D., Lembo, A. J., Simren, M., & Spiller, R. (2016). Bowel disorders.Gastroenterology 150 (6), 1393-1407.

This blog contains an interview with Alyson N Lowrey, PT, DPT, OCS. Alyson treats the pelvic floor patient population through an orthopedic approach, working closely with pelvic floor specialists. Alyson’s clinical interests include evaluation/treatment of chronic pain, lumbar and cervical spine disorders, foot and ankle disorders, pelvic pain, and clinical instruction. Alyson is the co-instructor for the new H&W course, Pain Science for the Chronic Pelvic Pain Population - Remote Course scheduled for July 17-18, 2021.

Q: Who are you? Describe your clinical practice.

A: I work in an outpatient hospital-based clinic where I am able to provide true 1:1 care to patients of all ages and orthopedic conditions. Since pelvic floor therapy came to our clinic, I have developed strong clinical and personal relationships with pelvic floor therapists. We have been able to successfully combine our respective expertise into a wholistic approach for improving patient’s functional outcomes. My knowledge and relationships with pelvic floor therapy have allowed me as an ortho clinician to recognize when a patient’s dysfunction may have a pelvic floor component and refer appropriately. I am also in a unique opportunity where my pelvic floor colleagues will co-treat or transition care of a patient to me to continue to improve their overall function by providing functional strengthening and neuromuscular re-education to the pelvic floor musculature and other supportive muscular systems. This relationship also allows us to treat comorbid orthopedic conditions and pelvic dysfunctions such as low back pain or SIJ dysfunction as well.

Q: How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

A: I became involved with pelvic rehabilitation through working in a clinic with Tara Sullivan. Her knowledge is immense and our working relationship has shaped and changed how I assess patients. My practice has expanded drastically knowing so much more about pelvic floor dysfunction. I also have personal struggles with pelvic pain, which has given me a patient’s perspective as well on how important pelvic rehabilitation is.

Q: If you could get a message out to other clinicians about pelvic rehab what would it be?

A: I would encourage all ortho clinicians to educate themselves on pelvic rehab. Pelvic rehab is not yet fully integrated into our DPT curriculums and is often treated as a very separate area of dysfunction. Integrating pelvic floor function and dysfunction into my ortho world has drastically changed how I see and treat many patients.

Q: What made you want to create this course, Pain Science for the Chronic Pelvic Pain Population?

A: Tara and I wanted to create this course to help other clinicians become more proficient at treating chronic pain. A large portion of our caseloads is chronic pain both generally and with pelvic conditions. Patients with these conditions are often overlooked and not treated appropriately by the medical system at large. They are often dismissed or mislead that they have something drastically wrong with them, or worse, nothing wrong with them at all. This population often has the most functional deficits and the worst clinical outcomes. We want to change that.

Q: What need does your course fill in the field of pelvic rehabilitation?

A: There is a need in rehabilitation and medicine to understand pain from a biopsychosocial approach and to treat chronic pain conditions from that perspective. Pain is complex, and treatment is complex. Chronic pelvic pain is a subdivision of prevalent chronic pain that is not talked about or treated often enough.

Q: Who, what demographic, would benefit from your course?

A: Any clinician who treats chronic pain conditions can benefit from this course.

If you would like to learn more about chronic pelvic pain, you can join Alyson at Pain Science for the Chronic Pelvic Pain Population - Remote Course scheduled for July 17-18, 2021.

Tina Allen, PT, PRPC has been a physical therapist since 1993 and has specialized exclusively in pelvic health in all genders and throughout the patient's life span for the past 28 years. She works at the University of Washington Medical Center in a multidisciplinary Pelvic Health Clinic where she collaborates with physicians to optimize patient recovery.

Manual Therapy for the Abdominal Wall instructs participants on manual myofascial techniques that can be utilized to assist with the treatment of abdominal scars, endometriosis, IC/PBS, and abdominal wall restrictions that impact pelvic girdle dysfunction. The abdominal wall plays an intricate role in our general movement, digestion, continence, and support.

Scar tissue limits range of motion and can perpetuate pain and dysfunctional movement. Myofascial techniques can loosen and break up scar tissue to restore normal function. This manual therapy should be performed in a slow and precise manner that can stimulate the nervous system and can be used to effectively treat several conditions including trauma, inflammatory responses, post-surgical procedures, and postural conditions.

The abdominal wall needs to allow for mobility of our organs and stability of our trunk. The superficial and deep fascial of the abdominal wall have direct connections to the pelvic floor fascia. They contribute to supportive dysfunction and myofascial restriction of the perineum with pelvic pain. Lumbar nerves travel through the abdominal wall, have sensory innervation in the perineum, and can be a source of testicular, labial, clitoral and scrotal pain. By addressing the abdominal wall with manual therapy techniques, we can further our patients' recovery.

In the upcoming 5-hour short format remote course, Manual Therapy for the Abdominal Wall, we will discuss: general myofascial interventions, the anatomy of the abdominal wall (including fascial and nerve connections with the pelvic floor), evaluation/assessment techniques of the abdominal wall, and via video and discussion we will cover techniques utilized in treating the abdominal wall myofascial tissues. Further discussion will include case studies and how we can apply these same techniques to the perineum.

Holly Tanner, PT, DPT, MA, OCS, WCS, PRPC, LMP, BCB-PMB, CCI is a faculty member and the Director of Education at Herman & Wallace. She owns a private practice that focuses on pelvic rehabilitation and on chronic myofascial pain. Along with H&W faculty member Stacey Futterman, she co-authored the Male Pelvic Floor course.

In the US, vasectomy is one of the most common procedures performed, and it is often completed in an outpatient setting with a local anesthetic. Fortunately for most folks, it’s well-tolerated and the advice to rest and ice is enough to allow full recovery. Unfortunately, there are those who don’t recover with ease and are left with chronic pain complications. This is a population that is often left out of the clinical rehabilitation setting, and there is not yet robust literature to catch up with the positive clinical results pelvic rehab providers observe when treating post-vasectomy pain.

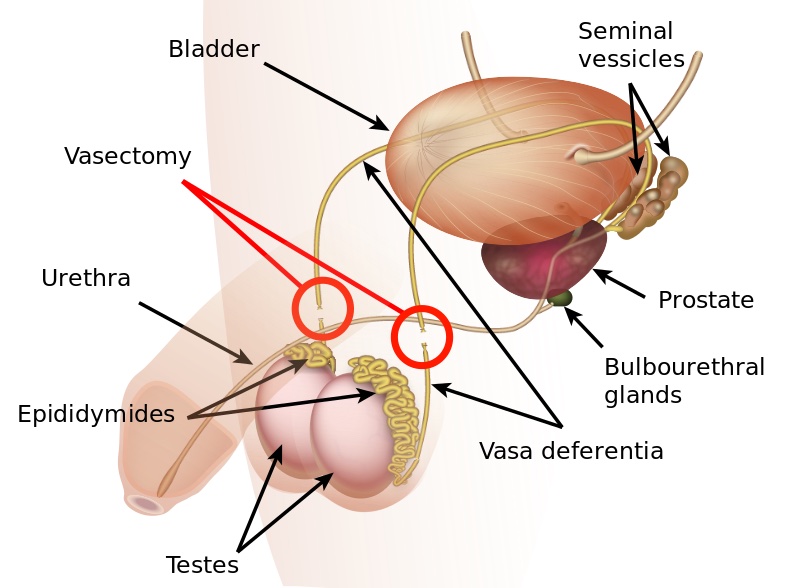

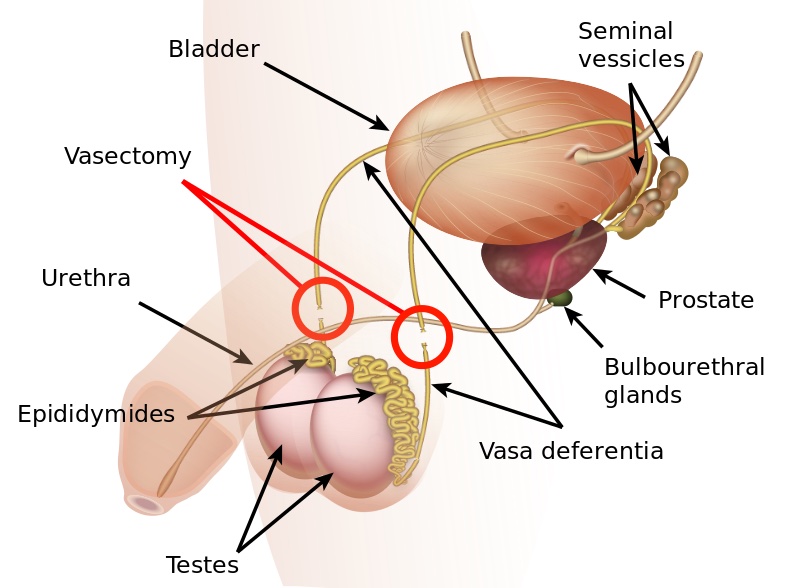

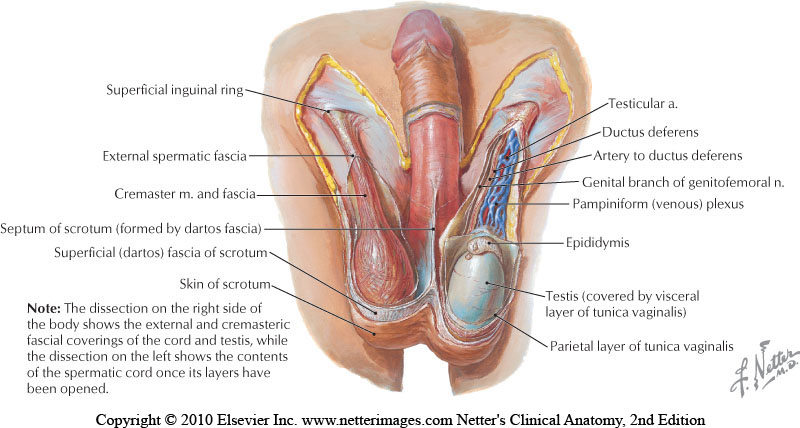

The Procedure

The goal of a vasectomy is typically contraception. The tube known as either the vas deferens or the ductus deferens is interrupted so that sperm does not travel to its typical destination outside the body via the urethra. This disruption in the tube takes place within the spermatic cord as it passes through the scrotum as this area is easily accessible. There are several techniques that can disrupt the tube where the sperm travels including, but not limited to, clamping, cauterization, or excision. The procedure leaves a small incision in the scrotal tissue.

Post-vasectomy Complications

Complications of a vasectomy may include bleeding and hematoma, infection, sperm granuloma (discussed below), chronic scrotal pain, seminal vesicle abscess (rare), and early or late canalization. (Sihra et al., 2007) Interestingly, some patients report less pain after vasectomy. (Leslie et al., 2007) Theories about the cause of post-vasectomy pain include interstitial fibrosis in the epididymal duct and perineurial fibrosis. (Lee et al., 2012) When we consider the anatomy, within the canal there may also be nerve irritation from the genitofemoral nerve, for example, or other connective tissues. If a patient had pain prior to the procedure in the low back, lower abdomen, or groin, the patient’s system may have been vulnerable to complications due to a sensitized system.

Examination & Rehab Efforts

When a patient presents with pain post-vasectomy, symptoms may worsen with prolonged sitting, with pressure from clothing, or in association with sexual or fitness activities. Because there has been a local insult to the tissues, it is logical to check the site of the procedure for any breakdown, signs of significant inflammation, swelling, and to examine for signs of infection such as fever. (Most patients have returned to their medical provider once pain develops, but if they haven’t, a referral is appropriate.) If the pain can be reproduced locally at the site of the procedure, the pain can often be managed by local treatment. You might find benefit in exam procedures such as a trunk or hip extension for the soft tissue tensioning as well as mechanical loading; palpation to the abdominal wall as well as within the spermatic cord. Treatment can address guarding of the area, general wellness (nutrition, movement, mental health), simple modalities such as heat, and gentle self-mobilization to the painful area.

Granulomas

Granulomas can form following a vasectomy, and while usually asymptomatic, a granuloma may be responsible for post-vasectomy pain. They are described as a “bag-like” structure with disintegrating spermatozoa that form at the cut ends of a vasectomy. (Chatterjee et al., 2001) If the granuloma is painful, very light manual mobilization of the thickened area may be done to alleviate pain (see image below). Mobilization of the spermatic cord itself via the testicle or more proximally may also prove helpful. Local modalities such as ultrasound or heat may improve symptoms as well, but clinically I have found that gentle manual therapy and movement exercises are enough to resolve the pain within a few weeks. Patients can be instructed to complete self-mobilization to the area of the granuloma, and as they often are scared to touch the area, helping alleviate this fear is useful in healing.

Post-vasectomy syndrome is very challenging for patients to manage, as they are often dismissed once the procedure is completed. Patients will share that they have been told “everything looks healed” and that the pain should go away on its own. Most providers are unaware of the role of pelvic rehab clinicians, and many pelvic rehab providers are less knowledgeable about conditions related to the scrotum and spermatic cord. For patients who do not respond to conservative intervention, vasectomy reversals have been found to be significantly helpful in reducing pain, though it’s often undesired due to the goal of contraception that inspired the vasectomy. (Herrel et al., 2015; Polackwith et al., 2015). Ideally, patients will be provided with an early recommendation to pelvic rehab so that further procedures or undoing of the vasectomy is avoided.

If you’d like to learn more about post-vasectomy syndrome and many other conditions that can go unrecognized and under-treated, the next opportunity to take the Male Pelvic Floor course is coming up July 9-10,2021!

Chatterjee, S., Rahman, M. M., Laloraya, M., & Pradeep Kumar, G. (2001). Sperm disposal system in spermatic granuloma: a link with superoxide radicals. International journal of andrology, 24(5), 278-283.

Herrel, L. A., Goodman, M., Goldstein, M., & Hsiao, W. (2015). Outcomes of microsurgical vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Urology, 85(4), 819-825.

Lee, J. Y., Chang, J. S., Lee, S. H., Ham, W. S., Cho, H. J., Yoo, T. K., ... & Lee, S. W. (2012). Efficacy of vasectomy reversal according to patency for the surgical treatment of postvasectomy pain syndrome. International journal of impotence research, 24(5), 202-205.

Leslie, T.A., R.O. Illing, D.W. Cranston, J. Guillebaud (2007). “The incidence of chronic scrotal pain after vasectomy: a prospective audit.” BJU International 100: 1330-1333.

Polackwich, A. S., Tadros, N. N., Ostrowski, K. A., Kent, J., Conlin, M. J., Hedges, J. C., & Fuchs, E. F. (2015). Vasectomy reversal for postvasectomy pain syndrome: a study and literature review. Urology, 86(2), 269-272.