The number of individuals who identify as transgender is growing each year. The Williams Institute estimated in 2016 that 0.6% of the U.S. population or roughly 1.4 million people identified as transgender (Flores, 2016). This was a 50% increase from a 2011 survey which estimated only 0.3% or 700,000 people identified as transgender (Gates, 2011). Though these numbers are growing each year, due to increased visibility and social acceptance, it is presumed that these numbers are underreported due to inadequate survey methods, stigma/fear associated with “coming out” and deficient definitions of the multitude of options for gender identity (Flores, 2016).

Though organizations such as WPATH have attempted to standardized care, the patient experience and reception of quality care are significantly lacking. In 2015 the National Center for Transgender Equality performed a groundbreaking survey of 27,215 respondents with the aim to “understand the lives and experiences of transgender people in the United States and the disparities that many transgender people face” (“About,”n.d., para. 1). This survey revealed that 33% of individuals who saw a health care provider had at least one negative experience related to being transgender (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Negative experiences included; being refused treatment, verbal harassment, physically or sexually assault, and teaching the provider about transgender people in order to get appropriate care (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Alternatively, 23% of respondents did not see a doctor when they needed to because of fear of being mistreated as a transgender person (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Though these statistics are staggering and affronting there is hope for a better future.

Research for the care of these patients, specifically related to pelvic floor physical therapy, is on the rise. In the Annals of Plastic Surgery, an article was published with the purpose to capture incidence and severity of pelvic floor dysfunction pre-surgery, monitor any progression of symptoms with standardized outcome measures and highlight the role of physical therapy in the treatment of patients undergoing vaginoplasty (Manrique, et al., 2019). While in the Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology a retrospective case series similarly focused on physical therapy pre and post-operatively highlighting dilator selection and success, pelvic floor dysfunction including bowel and bladder as well as reported abuse history (Jiang, Gallagher, Burchill, Berli, & Dugi, 2019). Through articles such as these clinicians can expect an uptick in calls questioning if they treat these patients. This begs the question of, "How can you best prepare?"

The answer is simple, attend continuing education. It is where you can not only learn evidence-based evaluation and treatment but also connect with other providers and mentors that care for these patients. In 2020 Herman & Wallace will be offering a continuing education course that serves this exact purpose. Keep your eyes on next years offerings, as spaces will surely fill quickly.

About. (n.d.). Retrieved May 15, 2019, from http://www.ustranssurvey.org/about

Dora Richter. (2019, May 09). Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Richter

Jiang, D. D., Gallagher, S., Burchill, L., Berli, J., & Dugi, D. (2019). Implementation of a Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy Program for Transgender Women Undergoing Gender-Affirming Vaginoplasty. Obstetrics & Gynecology,133(5), 1003-1011. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000003236

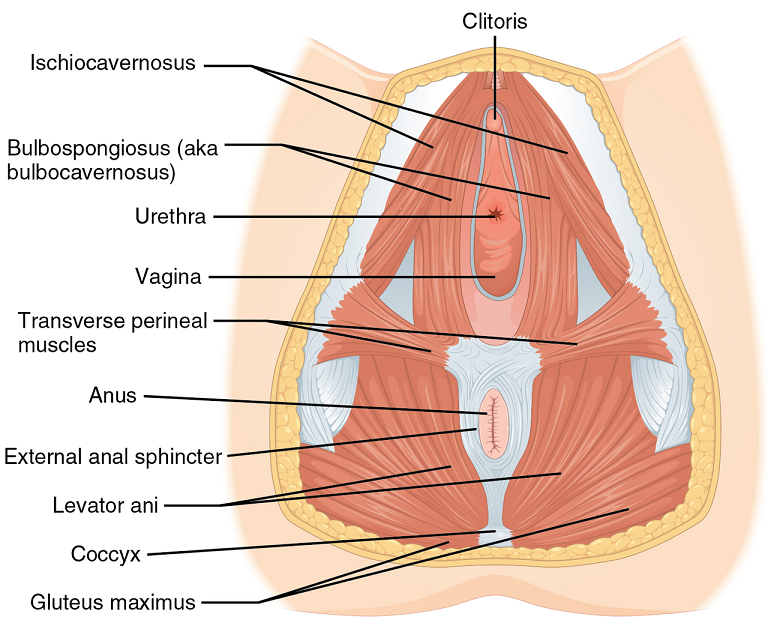

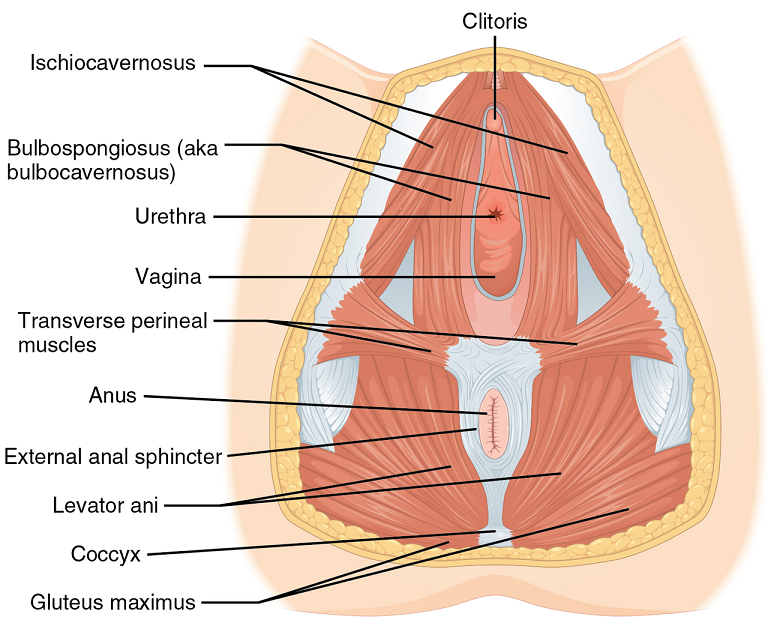

Manrique, O. J., Adabi, K., Huang, T. C., Jorge-Martinez, J., Meihofer, L. E., Brassard, P., & Galan, R. (2019). Assessment of Pelvic Floor Anatomy for Male-to-Female Vaginoplasty and the Role of Physical Therapy on Functional and Patient-Reported Outcomes. Annals of Plastic Surgery,82(6), 661-666. doi:10.1097/sap.0000000000001680

National Center for Transgender Equality. (2015). Annual report of the U.S. Transgender Survey. Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Executive-Summary-Dec17.pdf

Wpath. (n.d.). Standards of Care version 7. Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc

In this post, we want to give a high-level overview of interstitial cystitis and an introduction to other resources if you’d like to dive deeper into treatment the condition. There’s a printable, patient-friendly version of this overview if you’d like to use it in describing the condition with patients. In addition, you may want to review the 8 Myths of Interstitial Cystitis series and the AUA Guidelines for Interstitial Cystitis.

Definition

Interstitial cystitis is defined as pain or pressure perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes.

Unfortunately, for physicians, pelvic floor dysfunction falls under category of ‘unidentifiable cause.’ Interstitial cystitis is really more of a description of symptoms, rather than a discrete diagnosis, and the condition presents in many different ways.

Symptoms

The hallmarks of interstitial cystitis are pelvic pain, often in the suprapubic area or inner thighs, and urinary urgency and frequency. Other common symptoms include pain with intercourse, nocturia, low back pain, constipation, and urinary retention.

Many patients are surprised to realize that symptoms like painful intercourse, low back pain, and constipation are related to their IC diagnosis. This challenges the misconception that issues are arising solely from the bladder, and is a good way to help patients (and their physicians) understand that IC is about more than just the bladder.

Diagnosis

Interstitial cystitis is fundamentally a diagnosis of exclusion. Most patients suspect a urinary tract infection (UTI) when their symptoms first present. It’s actually common for symptoms to start as the result of a UTI, and simply not resolve once the infection has cleared. Patients are often treated with multiple rounds of antibiotics for these ‘phantom’ UTIs, where cultures have come back negative, before an IC diagnosis is considered.

It’s important for us as physical therapists to be able to share with patients that no testing is required to confirm an IC diagnosis, it can be diagnosed clinically. In practice, a urologist will likely want to conduct a cystoscopy, which can rule out more serious issues like bladder cancer as well as check for Hunner’s lesions (wounds in the bladder that are present in about 10% of IC patients). However, after that, no additional testing is needed. The potassium sensitivity test (PST) was formerly used by some urologists, but it has been shown to be useless diagnostically and extremely painful for patients and is not recommended by the American Urological Association. Urodynamic testing is also often conducted, but again is not necessary to establish an IC diagnosis.

Physical Therapy for IC

According to the American Urological Association, physical therapy is the most proven treatment for interstitial cystitis. It’s given an evidence grade of ‘A’ (the only treatment with that grade) and recommended in the first line of medical treatment.

In controlled clinical trials, manual physical therapy has been shown to benefit up to 85% of both men and women. These trials reported benefits after ten visits of one-hour treatment sessions.

In a study conducted at our clinic , PelvicSanity, we found that physical therapy was able to reduce pain for IC patients from an average of 7.6 (out of 10) before treatment to 2.6 following physical therapy. Similarly, how much their symptoms bothered patients fell from 8.3 to 2.8. More than half of patients reported improvements within the first three visits.

Unfortunately, many patients still aren’t referred to pelvic physical therapy by their physician. More than half of the patients in the study had seen more than 5 physicians before finding pelvic PT, and only 7% of patients felt they had been referred to physical therapy at the appropriate time by their doctor.

Multi-Disciplinary Approach

Patients with interstitial cystitis or pelvic pain always benefit from a multidisciplinary approach to treatment.This can include:

- Stress relief to downregulate the nervous system can decrease symptoms and reduce flares. Gentle exercise, meditation, yoga, deep breathing, or working with a psychologist can all provide benefits for patients.

- Diet and nutrition are important when working with IC patients. There is no formal ‘IC Diet’, but most patients are sensitive to at least a few trigger foods. The gold standard of treatment is an elimination diet, where the common culprits are completely removed from the diet and then added back in one at a time. This identifies which foods are triggers for patients. With nutrition for IC, patients should avoid their personal trigger foods and eat healthy – it doesn’t have to be any more restrictive or complicated.

- Alternative treatments like acupuncture have been shown to reduce pelvic pain in patients, and several supplements have shown benefits in trials or anecdotally among patients.

- Bladder treatments include instillations and nerve stimulation. Some patients may benefit from bladder instillations, but many others find that the process of the instillation actually causes additional symptoms. If instillations are beneficial, patients should be encouraged to address the underlying issues during the reprieve that instillations bring. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation or an implanted nerve stimulation device can both be possible treatment options.

- Oral medications can also reduce symptoms, but do not address the underlying cause of symptoms in patients. Medication that dampens the nervous system, often an anti-depressant or similar medication, can reduce pain and hypersensitivity. Anti-inflammatories may be beneficial in lowering inflammation and helping break the cycle of dysfunction-inflammation-pain. Most patients are started on Elmiron®, the only FDA-approved medication for IC; unfortunately, in the most recent clinical trial research Elmiron has been shown to be no more effective than a placebo. If it is effective, it only is beneficial for about one-third of patients, and many won’t be compliant with the drug due to cost and side effects.

Nicole Cozean, PT, DPT, WCS (www.pelvicsanity.com/about-nicole) is the founder of PelvicSanity physical therapy in Southern California. Name the 2017 PT of the Year by the ICN, she’s the first physical therapist to serve on the Interstitial Cystitis Association’s Board of Directors and the author of the award-winning book The IC Solution (www.pelvicsanity.com/the-ic-solution). She teaches at her alma mater, Chapman University, as well as continuing education through Herman & Wallace. Nicole also founded the Pelvic PT Huddle (www.facebook.com/groups/pelvicpthuddle), an online Facebook group for pelvic PTs to collaborate.

Nicole Cozean, PT, DPT, WCS (www.pelvicsanity.com/about-nicole) is the founder of PelvicSanity physical therapy in Southern California. Name the 2017 PT of the Year by the ICN, she’s the first physical therapist to serve on the Interstitial Cystitis Association’s Board of Directors and the author of the award-winning book The IC Solution (www.pelvicsanity.com/the-ic-solution). She teaches at her alma mater, Chapman University, as well as continuing education through Herman & Wallace. Nicole also founded the Pelvic PT Huddle (www.facebook.com/groups/pelvicpthuddle), an online Facebook group for pelvic PTs to collaborate.

Interstitial Cystitis Course

In our upcoming course for physical therapists in treating interstitial cystitis (April 6-7, 2019 in Princeton, New Jersey), we’ll focus on the most important physical therapy techniques for IC, home stretching and self-care programs, and information to guide patients in creating a holistic treatment plan. The course will delve into how to handle complex IC presentations. It’s a deep dive into the condition, focusing not just on manual treatment techniques but also how to successfully manage an IC patient from beginning to resolution of symptoms.

Additional Resources

- Interstitial Cystitis Overview (printable)

- The Interstitial Cystitis Solution

- Patient groups include the Interstitial Cystitis Association (ICA) (www.ic-help.org) and the IC Network (www.ic-network.com), which both have fantastic resources for patients.

- The AUA Guidelines for IC

- IC Flare-Busting Plan

Perineal massage involves pelvic floor muscle stretching by application of an external pressure to muscle and connective tissue in the perineal region. It is performed 4 to 6 weeks before childbirth to help the soft tissue in that region to withstand stretching during labor. This helps to prevent perineum during birth by decreasing the need for an episiotomy or an instrument-assisted delivery. Lengthening of skeletal muscles is known to modify the viscoelastic properties of the muscle-tendon unit, which decreases the tension peak of the musculature and therefore, chances of injury.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Instrument-assisted stretching is performed with the help of an inflatable silicon balloon that can be pumped to gradually stretch the vagina and perineum. However, the evidence to support its benefit is lacking. In fact, there is some concern that pelvic floor muscle stretching may cause a decrease in muscle strength. Some have argued that such exercise neither improve or worsen pelvic function (Labrecque M, et al., Medi-dan, et al.). While a meta-analysis by Aquino, et al. concluded that perineal massage during labor significantly lowered risk of severe perineal trauma, such as third and fourth degree lacerations (Aquino, et al.).

A recent major study done by deFreitas, et al., perineal massage and instrument-assisted stretching were found to improve perineal muscle extensibility when performed in multiple sessions on primiparous women beginning at 34th week of gestation, which is very helpful in preventing child trauma in labor; however, there was no increase in muscle strength.

The technique of performing the manual perineal massage (as exemplified in the aforementioned study) may involve two sessions per week for a month by an OBGYN-focused physiotherapist. The patients are rested in dorsal decubitus position with the inferior limbs semi-flexed and the lower limbs and feet supported on the examination table. Coconut oil can be used for the perineal massage - which starts off with circular movements in the external area of the vulva, around the vagina and in the central tendon of the perineum, followed by the index and middle fingers inserted approximately 4 cm in the vaginal introitus for an internal massage of the lateral walls of the vagina ending toward the anus, repeated four times on each side, with the whole process lasting approximately 10 minutes.

Instrument-assisted procedure may include inserting the instrument (Epi-No) covered with a condom and lubricated with a water-based gel, inflated at the vaginal introitus so that 2 cm of the balloon is visible, making sure the patient can tolerate the stretching, and are advised to keep the pelvic floor relaxed as the instrument is slowly expelled during expiration. Physiotherapist supervision is necessary in order to maintain the correct positioning of the balloon as it lengthens the muscles. He/she will also ensure proper expulsion of the equipment during expiration.

Overall, perineal massage techniques (with or without instrumentation) are beneficial in terms of preventing trauma during labor. There are many studies that support the efficacy of these techniques in doing so (Leon-Larios, et al.). But it is also important to appreciate the limitations and use it judiciously.

Randomized trial of perineal massage during pregnancy: perineal symptoms three months after delivery. Labrecque M, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000.

Perineal massage during pregnancy: a prospective controlled trial. Mei-dan E, et al. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008.

Perineal massage during labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aquino CI, et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018.

Effects of perineal preparation techniques on tissue extensibility and muscle strength: a pilot study. de Freitas SS, et al. Int Urogynecol J. 2018.

Influence of a pelvic floor training programme to prevent perineal trauma: A quasi-randomised controlled trial. Leon-Larios F, et al. Midwifery. 2017.

Earlier diagnosis is clearly a huge need for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. Many patients suffer with their symptoms for years before even hearing the words “pelvic floor,” or realizing that a pelvic floor physical therapist may be able to help. For interstitial cystitis, one large survey article found fewer than 10% of patients with the condition had been correctly diagnosed with IC, even after years of symptoms and visits with multiple doctors.

Even after being diagnosed, patients still don’t learn about how the pelvic floor can be causing or exacerbating their symptoms. In one study of our interstitial cystitis patients, 46% learned about the importance of the pelvic floor on their own and sought out treatment independently, while nearly half felt they were referred by their physician to physical therapy far too late, as a ‘last resort.’ This is despite the fact that many of these patients had seen five or more physicians and physical therapy is considered the most proven treatment for IC by the American Urological Association.

Physicians, orthopedic physical therapists, other practitioners, and patients themselves need a simple, proven way to identify pelvic floor dysfunction to help patients find pelvic floor physical therapy earlier in their medical journey.

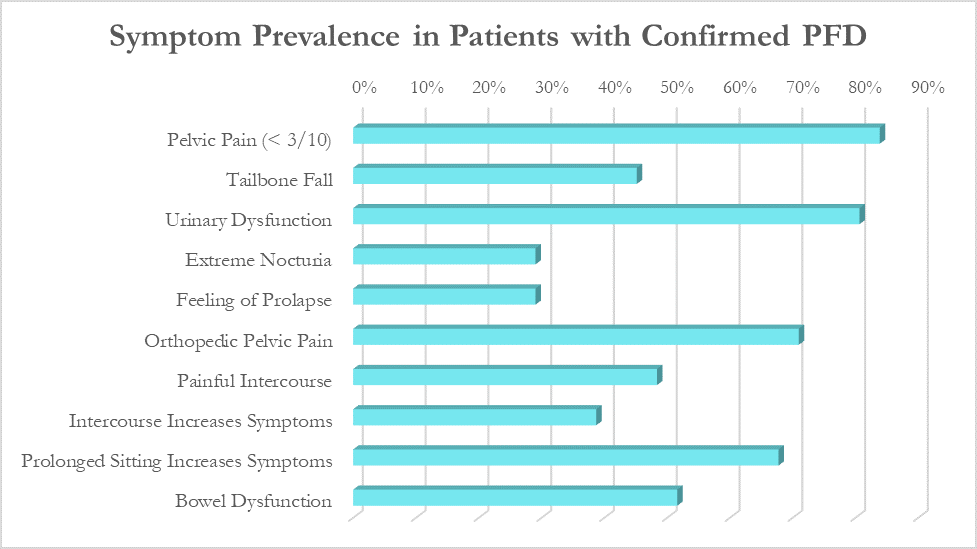

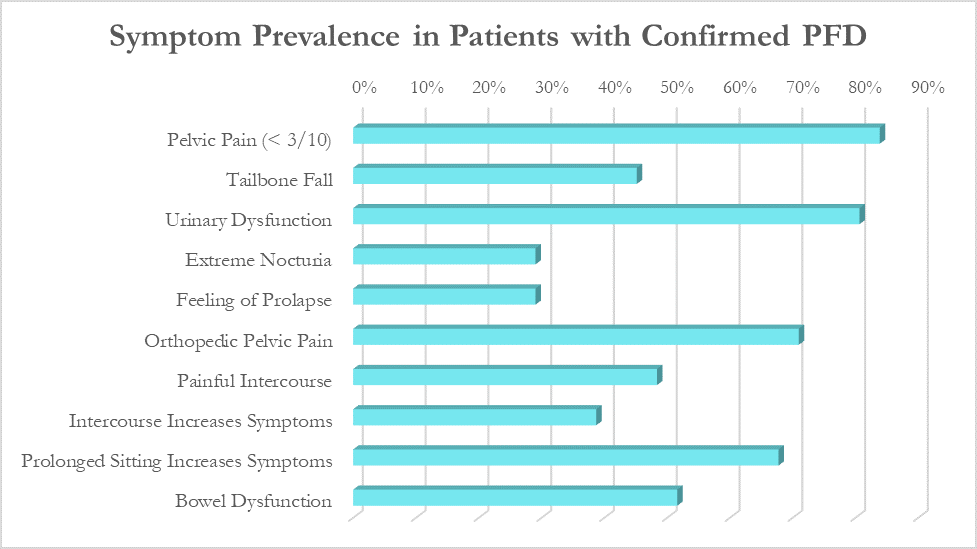

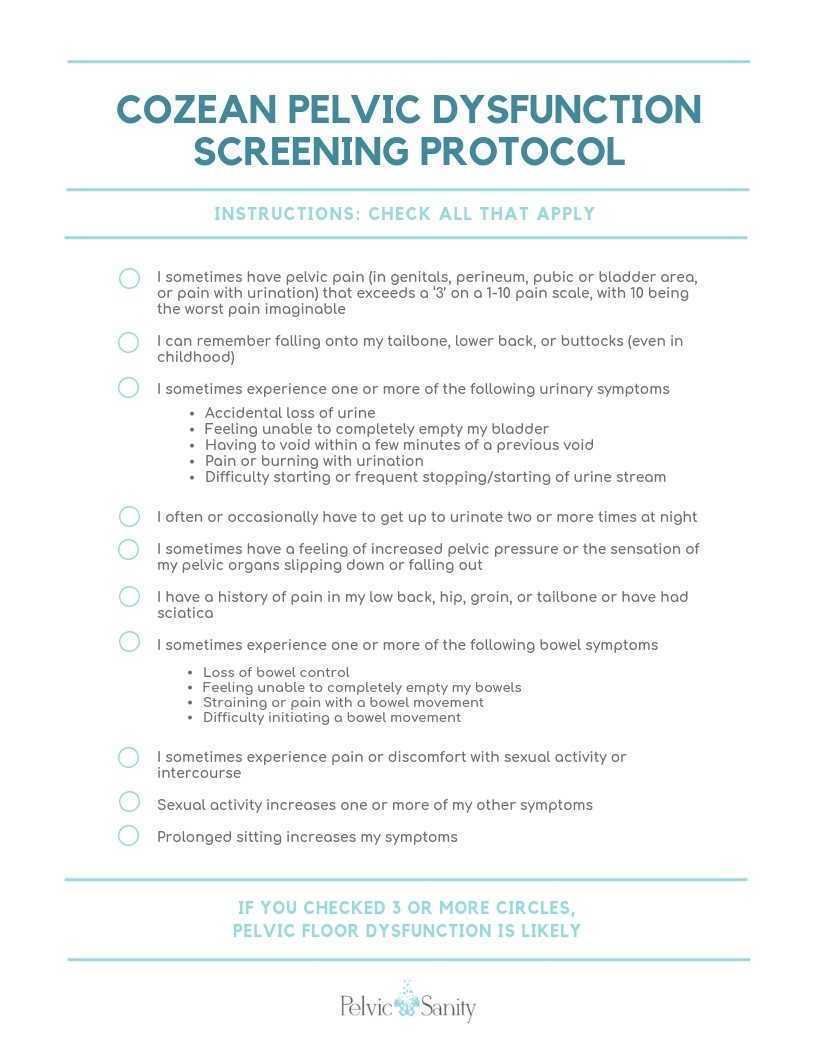

In a large survey of our patients with confirmed pelvic floor dysfunction, we examined what symptoms and medical history was most closely correlated with pelvic floor dysfunction. Any screening questionnaire would ideally be able to identify a wide variety of pelvic floor dysfunction, including patients with chronic pelvic pain, pelvic organ prolapse, orthopedic pain with a pelvic floor component (low back, hip, groin), urinary urgency/frequency, and/or bowel dysfunction.

While these patients all had different medical diagnoses, many symptoms were common across the patient population. The most common were pelvic pain (84%), urinary urgency, frequency, or incontinence (81%), orthopedic pelvic pain (71%) and symptoms that worsen with prolonged sitting (68%).

Based on the survey results, we created the Cozean Pelvic Dysfunction Screening Protocol to screen for pelvic floor dysfunction and published the results in the International Pelvic Pain Society (2017). The goal was to correctly identify more than 80% of the patients with pelvic floor dysfunction (sensitivity). For ease of use by both practitioners and patients, the questions were phrased so they could be answered with a simple ‘yes/no’ (as a check box). If patients answers ‘yes’ to 3 or more of the questions, pelvic floor dysfunction is highly likely.

Document available for download at https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/d1026c_42a0fda8e5644930950d754619586614.pdf

Document available for download at https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/d1026c_42a0fda8e5644930950d754619586614.pdf

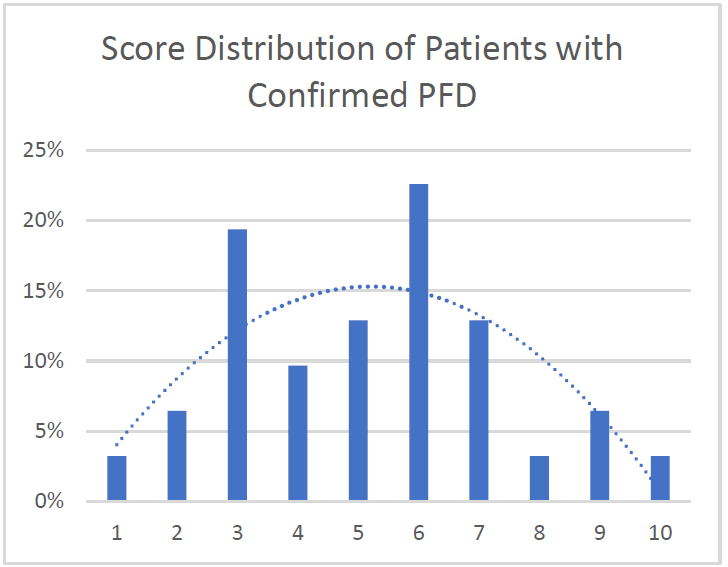

Testing the Model

In a model like this, we would expect a normal (bell-shaped) distribution curve of answers from patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. Some patients will score on the high end, others on the low, and the majority would be clustered in the middle. This is what we observe with use of the questionnaire, as seen by the trendline in the blow graph. Most patients with confirmed pelvic floor dysfunction cluster in scores between 3 and 7, with a few scoring at 8 or higher. Less than one out of ten patients with pelvic floor dysfunction score below a 2 on the questionnaire and would not be captured by this measure.

Specificity: 91%. More than 90% of patients with confirmed pelvic floor dysfunction were correctly identified by this screening protocol. Additional testing is required on a general population without PFD to determine the specificity of the questionnaire.

Average: 5.2. Of patients with confirmed PFD, the average score according to this screening protocol was 5.2 with a median score of 5 and a mode of 6. This is in line with what would be expected with a normal distribution curve.

We hope this 10-question survey is able to help patients with pelvic floor dysfunction be diagnosed earlier - whether by their physician, other physical therapists, or themselves – and seek pelvic floor physical therapy earlier in their medical journey. Please feel free to use the printable version of this protocol with your patients or in working with local practitioners.

Nicole Cozean will be teaching the course Interstitial Cystitis: Holistic Evaluation and Treatment in Princeton, NJ from April 6-7, 2019.

Nicole Cozean is the founder of PelvicSanity physical therapy, in Orange County, California. Nicole was named the 2017 PT of the Year, is the first physical therapist to serve on the ICA Board of Directors, and is the award-winning and best-selling book The Interstitial Cystitis Solution (2016). She is an adjunct professor at her alma mater, Chapman University and teaches continuing education courses through the prestigious Herman & Wallace Institute.

Nicole Cozean is the founder of PelvicSanity physical therapy, in Orange County, California. Nicole was named the 2017 PT of the Year, is the first physical therapist to serve on the ICA Board of Directors, and is the award-winning and best-selling book The Interstitial Cystitis Solution (2016). She is an adjunct professor at her alma mater, Chapman University and teaches continuing education courses through the prestigious Herman & Wallace Institute.

The following is a guest post from Nancy Fish, LCSW, MPH who will be presenting at the Alliance for Pelvic Pain Retreat on May 20-22 in Ellenville, NY. Check out this flier to learn more about the retreat.

Gaining a Sense of Hope and Empowerment

Nancy Fish, LCSW, MPH (co-author, with Deborah Coady,M.D. of Healing Painful Sex)

About the Alliance For Pelvic Pain Retreat, May 20-22, 2016, Ellenville, NY

When thinking about registering for the Alliance for Pelvic Pain Patient Retreat, I imagine you are asking yourself “Why would a person suffering from pelvic pain, with more medical appointments than is humanly possible to handle, add another item on an already overwhelming “to do” list?” It would be completely understandable if that is your initial reaction. So why is this retreat a must in your path to physical and emotional healing? There are so many reasons why this retreat can be a life-altering event but I’ll just name a few compelling ones. As a psychotherapist who specializes in pelvic pain (I am also a pelvic pain patient) the primary challenges I hear from most of my clients are:

- “I feel so alone.”

- “This is too embarrassing to talk about with ANYONE.”

- ”I feel so hopeless and that there is nothing that can help me.”

- “I feel like I will never have sex again.”

- “Who will want me?”

- “No doctor understands this and no doctor can help me.”

If you are reading this blog, I’m sure you can identify with a few if not all of these statements. If only ONE of these statements is something you relate to, then the AFPP retreat is an event you cannot afford to miss. It will provide you with invaluable tools to address all of your concerns. You will have access to some of the world’s most renowned medical, physical therapy, and mental health professionals specializing in the integrative treatment of pelvic pain who will be able to answer any of your questions or concerns. There will be opportunities to register for significantly discounted one on one sessions with expert physical therapists, an Acupuncturist, a yoga instructor, and services from the EarthMind Wellness Center at Honors Haven. You will also be with other individuals who share the same concerns and challenges and you will not have to explain issues like “why you can’t sit” or “why this pain makes you feel you are going crazy.” For the first time in a long time you will not have to justify behaviors or decisions that you are confronted with on a daily basis – you can just be you.

One of the greatest tools you will gain from this retreat is empowerment. Pelvic pain can be so disempowering and our goal is give you the ability to empower yourself so you begin or continue on the path of self-healing through a combination of medical and integrative health techniques. I never ask any of my clients to use a technique that I don’t use myself. And I have found that medical interventions are often essential but not enough. Overcoming pelvic pain takes an “East meets the West” approach using a daily practice of mindfulness, meditation, and other integrative techniques. Participants leave the retreat with a new support system, a sense of self-empowerment, and a host of self-healing practices (such as a physical therapy home program) that will be invaluable on your journey to recovery – and most important, A RENEWED SENSE OF HOPE.

(Spaces are limited so please book your reservation as soon as possible. Also, for funding opportunities, all participants should go to Gofundme.com.)