Rehabilitative ultrasound imaging has been used in clinical practice for well over a decade now. It has been used for core stabilization, as well as with female incontinence patients. In recent years, transperineal ultrasound imaging has emerged as a useful tool for assessing prolapses and identifying other women’s health issues in the anterior compartment.

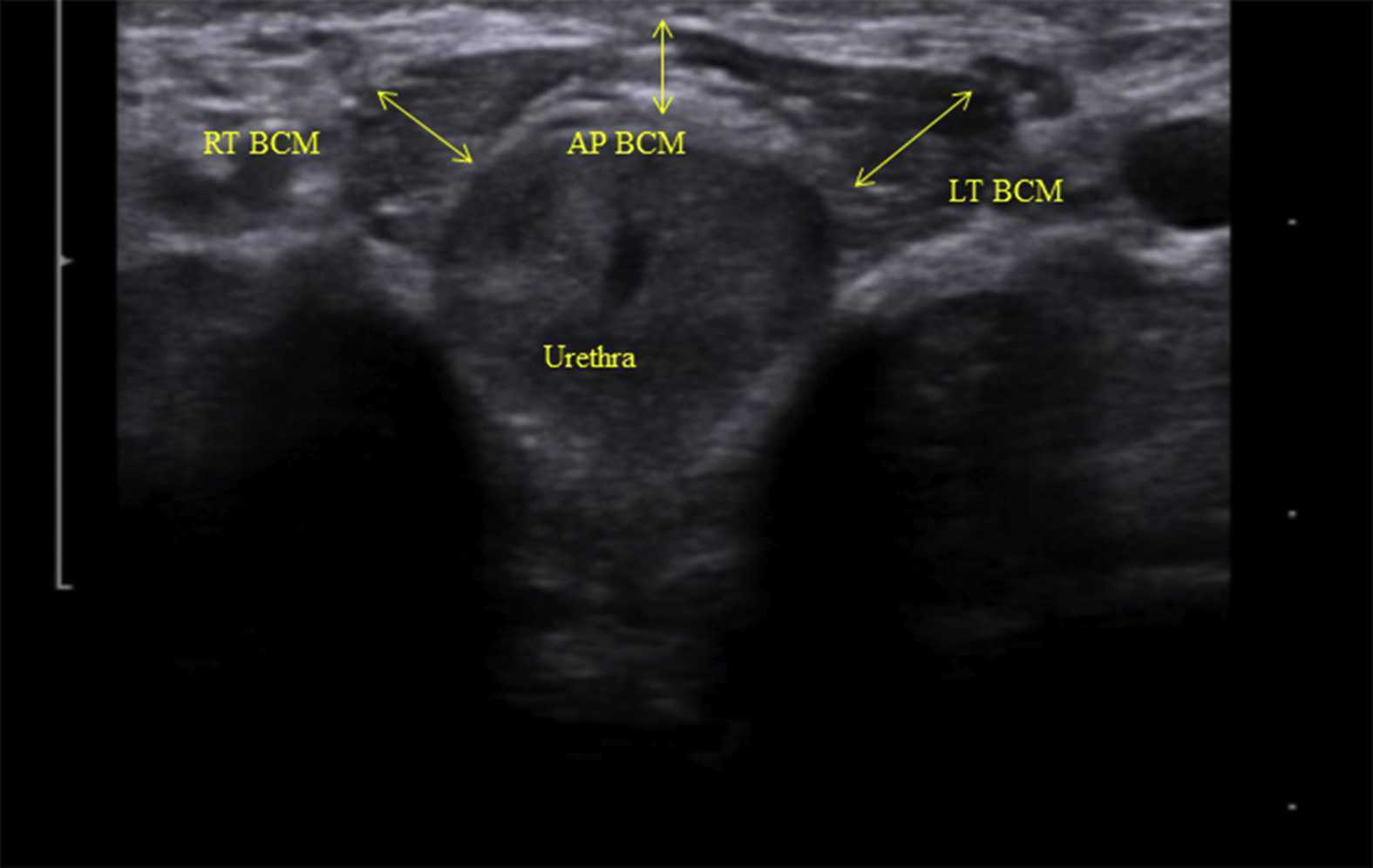

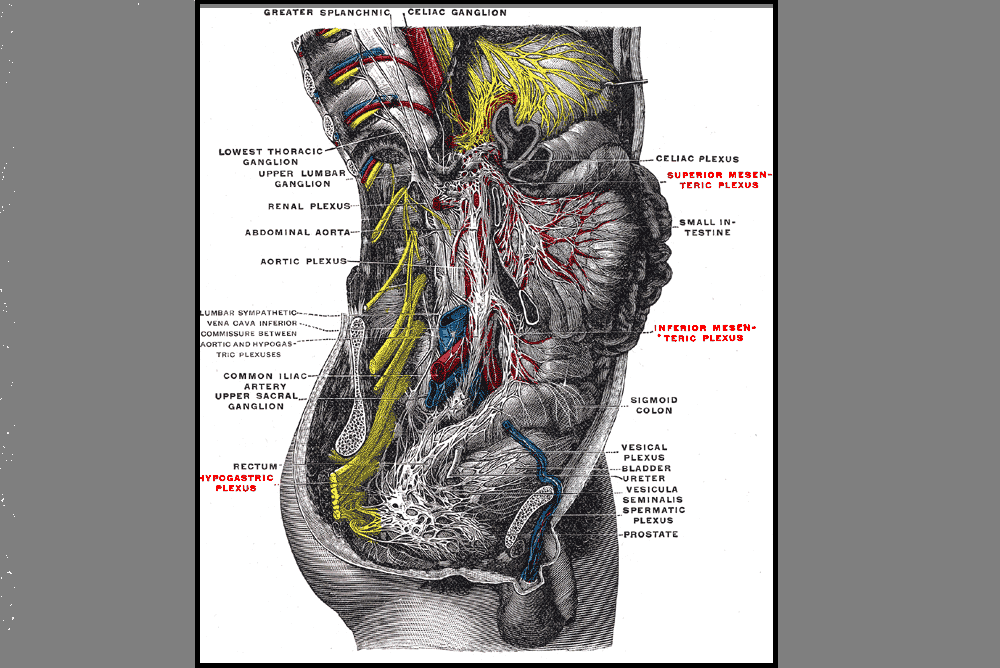

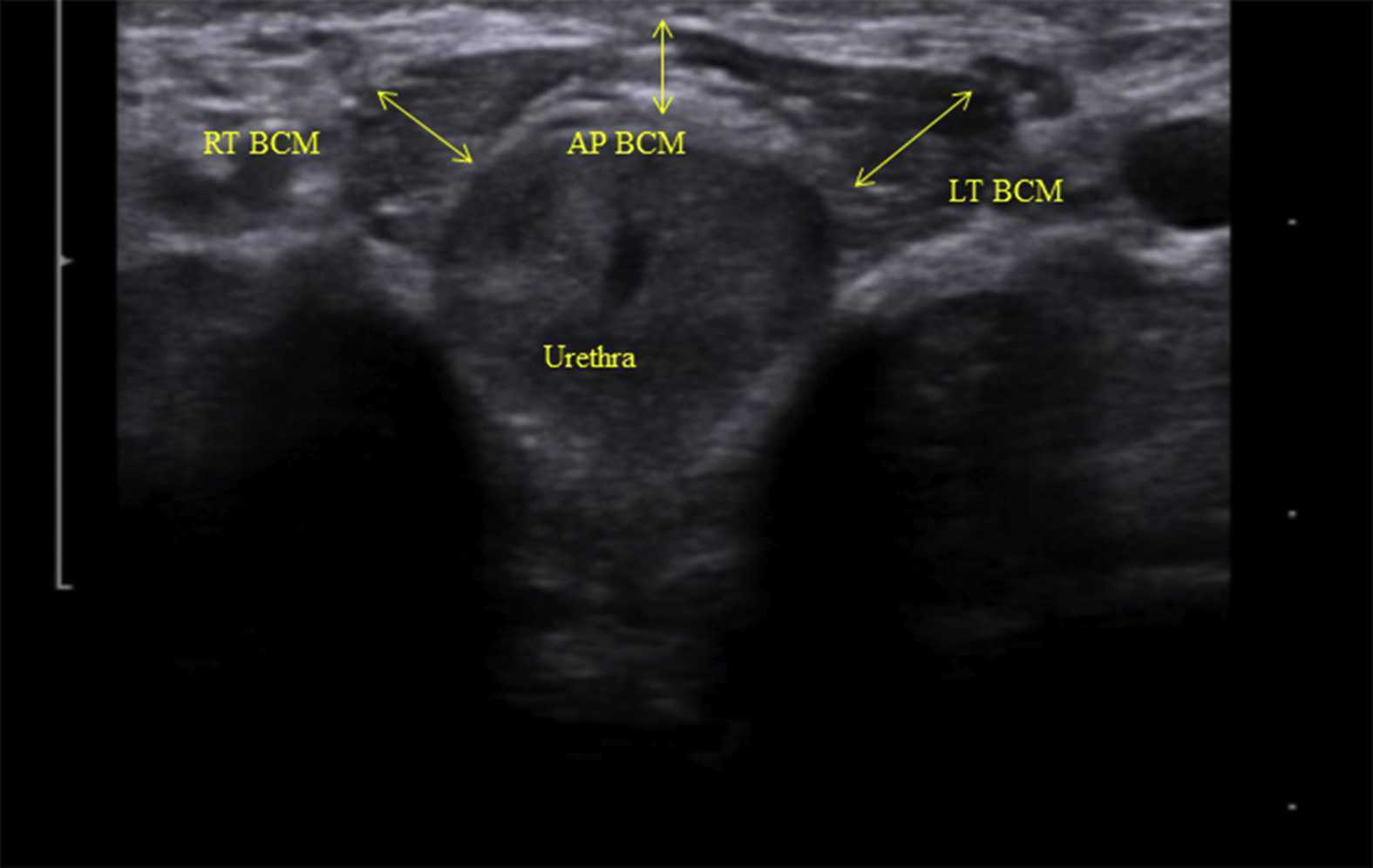

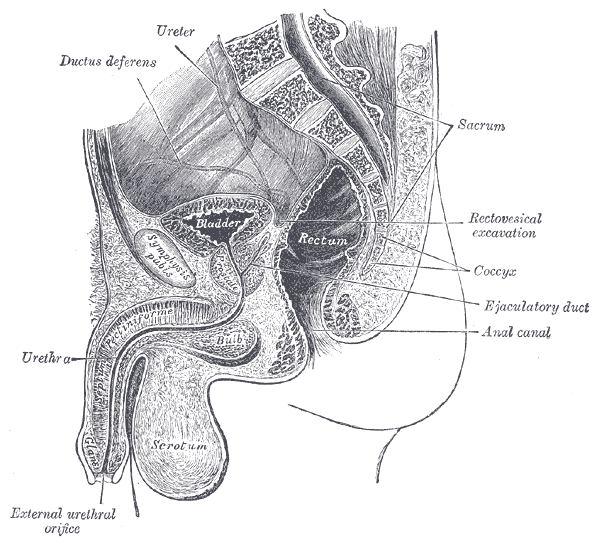

Like other things in men’s pelvic health, the use of ultrasound imaging for rehabilitation has lagged behind that in women’s pelvic health. Ryan Stafford is a researcher that is working to change that. In 2012, Stafford began looking at the normal responses to pelvic floor contractions and what is seen on ultrasound in men. He has since taken his research further to examine differences in men that present with post-prostatectomy incontinence. Stafford, van den Hoorn, Coughlin, and Hodges performed a study looking at the dynamic features of activation of specific pelvic floor muscles, and anatomical parameters of the urethra. The study included forty-two men who had undergone prostatectomy. Some of these men were incontinent and others remained continent. Transperineal ultrasound imaging was used to obtain images of the pelvic structures during a cough, and a sustained maximal contraction. The research team calculated displacements of pelvic floor landmarks with contraction, as well as anatomical features including urethral length, and resting position of the ano-rectal and urethra-vesical junctions.

Like other things in men’s pelvic health, the use of ultrasound imaging for rehabilitation has lagged behind that in women’s pelvic health. Ryan Stafford is a researcher that is working to change that. In 2012, Stafford began looking at the normal responses to pelvic floor contractions and what is seen on ultrasound in men. He has since taken his research further to examine differences in men that present with post-prostatectomy incontinence. Stafford, van den Hoorn, Coughlin, and Hodges performed a study looking at the dynamic features of activation of specific pelvic floor muscles, and anatomical parameters of the urethra. The study included forty-two men who had undergone prostatectomy. Some of these men were incontinent and others remained continent. Transperineal ultrasound imaging was used to obtain images of the pelvic structures during a cough, and a sustained maximal contraction. The research team calculated displacements of pelvic floor landmarks with contraction, as well as anatomical features including urethral length, and resting position of the ano-rectal and urethra-vesical junctions.

The data was analyzed and combinations of variables that best distinguished men with and without incontinence were reported. Several important components were identified in the study. Striated urethral sphincter activation, as well as bulbocavernosus and puborectalis muscle activation were significantly different between men with and without incontinence. When these two parameters were examined together, they were able to correctly identify 88.1% of incontinent men. They further reported that poor function of the puborectalis and bulbocavernosus could be compensated for if the man had good striated urethral sphincter function. However, the puborectalis and bulbocavernosus had less potential to compensate for poor striated urethral sphincter function. This is important for a therapist that works with post prostatectomy patients to know. This can explain part of why some men improve and do so well after a prostatectomy and others don’t, even with therapy to help. If the striated urethra sphincter is damaged and its normal responses are changed during surgery, then incontinence after prostatectomy may be more likely.

Using ultrasound imaging, the therapist can examine and see exactly where a man is deficient in response; whether it is the puborectalis, or the striated urethra sphincter. It is exciting to see this new research and see how rehabilitative ultrasound imaging can influence men’s pelvic health! Come and learn how to use ultrasound imaging for your men’s pelvic health patients as well as your women’s health and back pain patients! You will see how ultrasound imaging can change your practice and how much your patients will enjoy seeing real-time images of their contractions! Thanks to our partnership with The Prometheus Group, this course includes hands-on training on the latest in pelvic ultrasound imaging.

1. Stafford R, Ashton-Miller J, Constantinou C, et al. Novel insights into the dynamics of male pelvic floor contractions through transperineal ultrasound imaging. J. Urol. 2012; 188: 1224-30.

2. Stafford RE, van den Hoorn W, Couglin G, Hodges P. Postprostatectomy incontinence is related to pelvic floor displacements observed with trans-perineal ultrasound imaging. Neurol and Urodyn. 2018; 37:658-665.

Image credit Gupta et al. 2016 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2016.11.002 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214388216300881#fig2

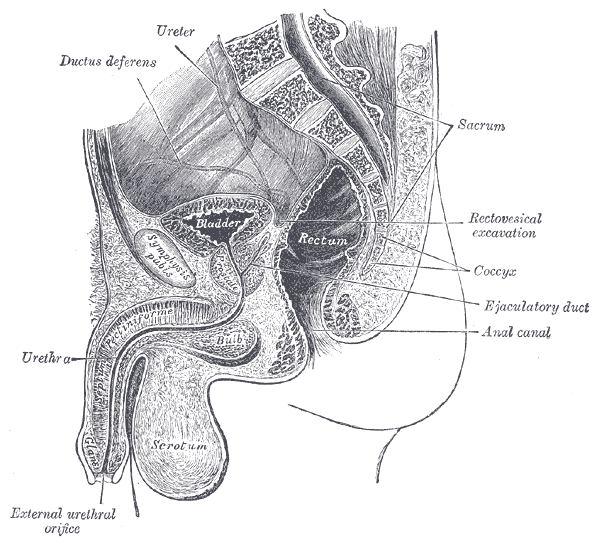

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a debilitation complication of radical prostatectomy, which is a treatment for prostate cancer. ED is caused by a variety of causes, diabetic vasculopathy, smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, psychological issues, peripheral vascular disease and medication; we will focus on post-prostatectomy ED and the role of penile rehabilitation in its management.

Post-prostatectomy-related Erectile dysfunction

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Research on penile hemodynamics in these patients have shown that venous leakage is also implicated in its pathophysiology. An injury to the neurovascular bundles likely leads to smooth muscle cell death, which then leads to irreversible veno-occlusive disease.

There is a potential role of hypoxia in stimulating growth factors (TGF-beta) that stimulate collagen synthesis in cavernosal smooth muscle. Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) was found to suppress the effect of TGF-β1 on collagen synthesis.

Role of Penile Rehabilitation

The goal of Penile Rehabilitation is to limit and reverse ED in post-prostatectomy patients. The idea is to minimize fibrotic changes during the period of “penile quiescence” after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Several approaches have been tried, including PGE1 injection, vacuum devices, and phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors.

Mulhall and coworkers followed 132 patients through an 18-month period after they were placed in “rehabilitation” or “no rehabilitation” groups after radical prostatectomy, and 52% of those undergoing rehabilitation (sildenafil + alprostadil) reported spontaneous functional erections, compared with 19% of the men in the no-rehabilitation group 2.

Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1)

Alprostadil is a vasodilatory prostaglandin E1 that can be injected into the penis or placement in the urethra in order to treat ED. Montorsi, et al. studied the use of intracorporeal injections of alprostadil starting at 1 month after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and reported a higher rate of spontaneous erections after 6 months compared with no treatment 3. Gontero, et al. investigated alprostadil injections at various time points after non–nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and found that 70% of patients receiving injections within the first 3 months were able to achieve erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 40% of patients receiving injections after the first 3 months 4.

Vacuum constriction device (VCD)

VCD is an external pump that is used to get and maintain an erection. Raina, et al evaluated the daily use of a VCD beginning within two months after radical prostatectomy, and reported that after 9 months of treatment, 17% of patients using the device had return of natural erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 11% of patients in the nontreatment group 4.

PDE-5 Inhibitors

PDE-5 inhibitors (such as Sildenafil) are the first-line treatment for ED of many etiologies. Several studies have shown that the use of PDE-5 inhibitors might lead to an overall improvement in endothelial cell function in the corpus cavernosum. Chronic use of oral PDE-5 inhibitors suggest a beneficial effect on endothelial cell function. Desouza, et al. concluded that daily sildenafil improves overall vascular endothelial cell function. However, Zagaja, et al. found that men taking oral sildenafil within the first 9 months of a nerve-sparing procedure did not have any erectogenic response 4.

Overall, accumulating scientific literature is suggesting that penile rehabilitation therapies have a positive impact on the sexual function outcome in post-prostatectomy patients. It must be noted that these methods do not cure ED and should be used with caution.

1Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701-1705.

2Mulhall J, Land S, Parker M, et al. The use of an erectogenic pharmacotherapy regimen following radical prostatectomy improves recovery of spontaneous erectile function. J Sex Med. 2005; 2:532-540.

3Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Strambi LF, et al. Recovery of spontaneous erectile function after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy with and without early intracavernous injections of alprostadil: results of a prospective, randomised trial. J Urol. 1997;158:1408-1410.

4Gontero P, Fontana F, Bagnasacco A, et al. Is there an optimal time for intracavernous prostaglandin E1 rehabilitation following non- nerve sparing radical prostatectomy? Results from a hemodynamic prospective study. J Urol. 2003;169:2166-2169.

Managing a medical crisis such as a cancer diagnosis can be overwhelming for an individual. Faced with choices about medical options, dealing with disruptions in work, home and family life often leaves little energy left to consider sexual health and intimacy. Maintaining closeness, however, is often a goal within a partnership and can aid in sustaining a relationship through such a crisis. The research is clear about cancer treatment being disruptive to sexual health, yet intimacy is a larger concept that may be fostered even when sexual activity is impaired or interrupted. Last year, when I was asked to speak to the Pacific NW Prostate Cancer Conference about intimacy, I was pleasantly surprised to find a rich body of literature about maintaining intimacy despite a diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

If the patient brings up sexual health, or we encourage the conversation, there are many research-based suggestions we can provide to encourage recovery of intimacy, several are listed below.

- Manage general health, fitness, nutrition, sleep, anxiety and stress

- Redefine sex as being beyond penetration, consider other sexual practices such as massage/touch, cuddling, talking, use of vibrators, medication, aids such as pumps (Usher et al., 2013)

- Participate in couples therapy to understand partners’ needs, address loss, be educated about sexual function (Wittman et al., 2014; Wittman et al., 2015)

- Participate in “sensate focus” activities (developed by Masters & Johnson in 1970’s as “touch opportunities”) with appropriate guidance (Weiner & Avery-Clark 2017)

Within the context of this information, there is opportunity to refer the patient to a provider who specializes in sexual health and function. While some rehabilitation professionals are taking additional training to be able to provide a level of sexual health education and counseling, most pelvic health providers do not have the breadth and depth of training required to provide counseling techniques related to sexual health- we can, however, get the conversation started, which in the end may be most important.

In the men’s health course, we further discuss sexual anatomy and physiology, prostate issues, and look at the research describing models of intimacy and what worked for couples who did learn to renegotiate intimacy after prostate cancer.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2009, April). Sexual intimacy in heterosexual couples after prostate cancer treatment: What we know and what we still need to learn. In Urologic oncology: seminars and original investigations (Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 137-143). Elsevier.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2013). Sexual Values as the Key to Maintaining Satisfying Sex After Prostate Cancer Treatment : The Physical Pleasure–Relational Intimacy Model of Sexual Motivation. Archives of sexual behavior, 42(8), 1637-1647.

Gilbert, E., Ussher, J. M., & Perz, J. (2010). Renegotiating sexuality and intimacy in the context of cancer: the experiences of carers. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 998-1009.

Hawkins, Y., Ussher, J., Gilbert, E., Perz, J., Sandoval, M., & Sundquist, K. (2009). Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer nursing, 32(4), 271-280.

Higano, C. S. (2012). Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(30), 3720-3725.

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E., Wong, W. T., & Hobbs, K. (2013). Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nursing, 36(6), 454-462.

Weiner, L., Avery-Clark, C. (2017). Sensate Focus in Sex Therapy: The Illustrated Manual. Routledge, New York.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., An, L., Palapattu, G., & Montie, J. E. (2014). Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(9), 2509-2515.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., Crossley, H., An, L., ... & Montie, J. E. (2015). What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: toward the development of a conceptual model of couples' sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. The journal of sexual medicine, 12(2), 494-504.

The following is a guest submission from Alysson Striner, PT, DPT, PRPC. Dr. Striner became a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) in May of 2018. She specializes in pelvic rehabilitation, general outpatient orthopedics, and aquatics and treats at Carondelet St Joesph’s Hospital in the Speciality Rehab Clinic located in Tucson, Arizona.

Recently, I had a patient present with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) on his right foot. He stated that the pain had started about 10 days after his prostatectomy when someone had fallen onto his right foot. He reported a bunionectomy on that foot 7 years prior and noted an episode of plantar facilities before his prostatectomy. CRPS is defined as “chronic neurologic condition involving the limbs characterized by severe pain along with sensory, autonomic, motor, and trophic impairments” in a 2017 article "Complex regional pain syndrome; a recent update" by Goh, En Lin. The article goes on to discuss how CRPS can set off a cascade of problems including altered cutaneous innervation, central and peripheral sensitization, altered sympathetic nervous system function, circulating catecholamines, changes in autoimmunity, and neuroplasticity.

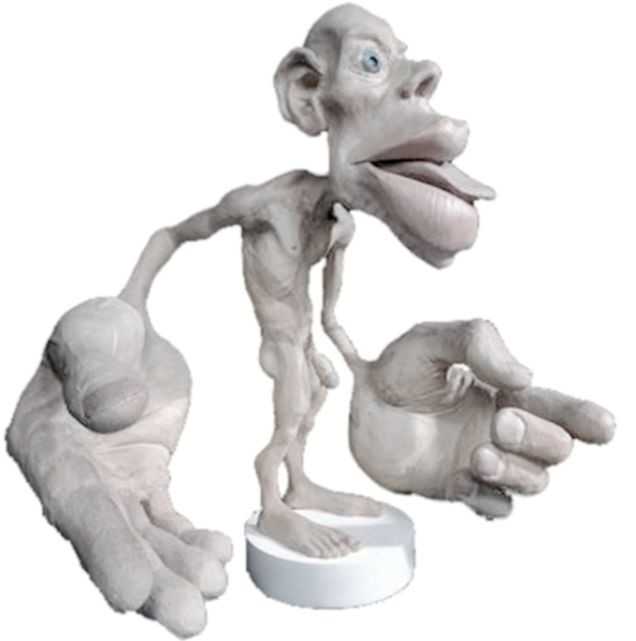

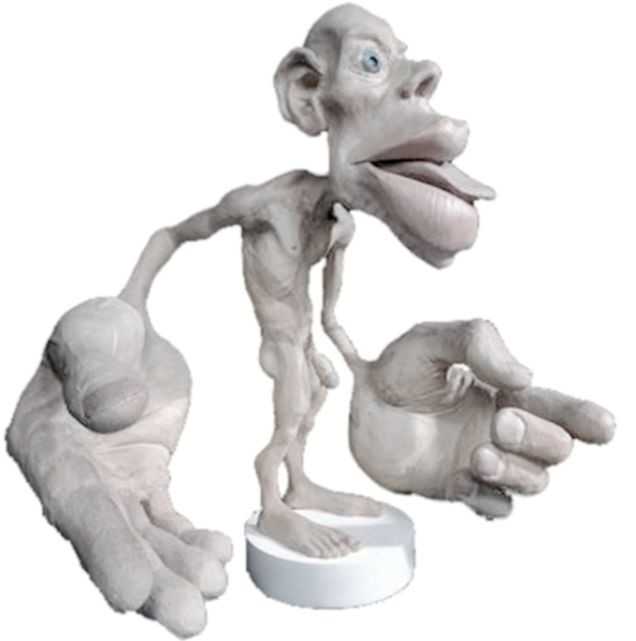

A recent persistent pain theory to explain the relationship between pelvic floor and his foot could be overflow or ‘smudging’ in his homunculus. The homunculus is the map of our physical body in our brain where the feet are located next to the genitals. Possibly when one has pain, there can be ‘smudging’ of our mental body map from one area into another. I have heard this explained as though a chalk or charcoal drawing has been swipes their hand through the picture. A recent study by Schrabrun, SM et al “Smudging of the Motor Cortex is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain” found that people with chronic low back pain had a loss of cortical organization which and that this loss was associated with the severity and location of LBP.

A recent persistent pain theory to explain the relationship between pelvic floor and his foot could be overflow or ‘smudging’ in his homunculus. The homunculus is the map of our physical body in our brain where the feet are located next to the genitals. Possibly when one has pain, there can be ‘smudging’ of our mental body map from one area into another. I have heard this explained as though a chalk or charcoal drawing has been swipes their hand through the picture. A recent study by Schrabrun, SM et al “Smudging of the Motor Cortex is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain” found that people with chronic low back pain had a loss of cortical organization which and that this loss was associated with the severity and location of LBP.

There are many ways to improve the organization of the homunculus and create neuroplasticity. One such way was suggested is with Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) to the bottom of the foot to affect bladder spasms and pain. In recent study, “Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of somatic afferent nerves of the foot relieved symptoms related to postoperative bladder spasms,". Zhang, C et al. 2017 found that participates that had either a bladder surgery or a prostate surgery had improvement in bladder spasm symptoms and VAS scores on day two and three. Their protocol was to use two electrodes over the bottom of the foot at 5 Hz with 0.2 millisecond pulse width until a muscle twitch was achieved and was increased, but still comfortable for an hour (there is a picture of electrode placement in the article). The authors note that this neuromodulation of the foot sensory nerves may inhibit interactions between the somatic peripheral neuropathway and autonomic micturition reflex to calm the bladder and pain.

No matter what we do to help calm nervous systems from the top down; pain neuroscience education, mindful based relaxation, graded motor imagery, or from the bottom up; de-sensitization, biofeedback, or good old-fashioned TENS. The result is the same; a cortical organization and happier patients.

En Lin Goh†, Swathikan Chidambaram† and Daqing Ma. "Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update". Burns & Trauma 2017 5:2.https://doi.org/10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4"

Schabrun SM, Elgueta-Cancino EL, Hodges PW. "Smudging of the Motor Cortex Is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain." Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017 Aug 1;42(15):1172-1178. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000938

Chanjuan Zhang, et al. "Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of somatic afferent nerves in the foot relieved symptoms related to postoperative bladder spasms". BMC Urol. 2017; 17: 58. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0248-9

Sara Chan Reardon, DPT, WCS, BCB-PMD is a pelvic floor dysfunction specialist practicing in New Orleans, LA. Sara was named the 2008 Section on Women’s Health Research Scholar for her published research on pelvic floor dyssynergia related constipation. She was recognized as an Emerging Leader in 2013 by the American Physical Therapy Association. She served as Treasurer of the APTA’s Section on Women's Health and sat on their Executive Board of Directors from 2012-2015. Today she was kind enough to share a bit about her course Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation, which is taking place twice in 2018.

My name is Sara Reardon, and I teach the Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation course, which I wrote and developed in the year 2015. At the time, I had been a pelvic health Physical Therapist for over 10 years. Earlier in my career, I had taken the Pelvic Floor 2A course by Herman and Wallace Institute, which was a fantastic and thorough introduction to treating a male patient.

My name is Sara Reardon, and I teach the Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation course, which I wrote and developed in the year 2015. At the time, I had been a pelvic health Physical Therapist for over 10 years. Earlier in my career, I had taken the Pelvic Floor 2A course by Herman and Wallace Institute, which was a fantastic and thorough introduction to treating a male patient.

Over the years, I started seeing more and more men with post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction in my clinic. Urinary incontinence is the most common and costly complication in men following prostate removal surgery, and their quality of life is directly related to their duration of experiencing those symptoms. Evidence supports that pelvic floor muscle training started as soon as possible after surgery can help decrease incontinence and improve quality of life. I enjoyed being able to help men decrease their incontinence and improve their other symptoms after all they had been through following a cancer diagnosis and treatment.

No courses focused specifically on treating post-prostatectomy pelvic floor dysfunction were offered at the time, so I scoured the research, shadowed with physicians, observed surgeries, and attended urology conferences to understand how to effectively treat these individuals. Treating this population of men is fun, fulfilling, and rewarding, and I was inspired to help other pelvic health physical therapists dive deeper as I witnessed the impact pelvic health physical therapy can have on the quality of life of these patients. I love teaching this course, and I am excited to help other pelvic health professionals learn evidence based and effective treatment strategies to help these men navigate their recovery after prostatectomy.

Join Dr. Reardon in Philadelphia, PA on June 2-3, 2018 or in Houston, TX on November 10-11, 2018 to learn evaluation and treatment techniques for men recovering from prostatectomy surgery.