This week for the Pelvic Rehab Report, Holly Tanner sat down to interview faculty member Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC on her specialty course Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation. If you would like to learn more about working with this patient population join Erica on June 24th-25th for the next course date!

This is Holly Tanner with the Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehab Institute and I'm here with Erica Vitek who's going to tell us about of course that she has created for Herman and Wallace. Erica, will you tell us a little bit about your background?

Yes. Absolutely. Thanks for chatting with me today about my course! So my course is Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation. I'm just so excited to be part of the team and to be sharing all this great information. How I got the idea for the course is that there was a need for more neuro-type topics related to pelvic health, and individuals were reaching out to me because my specialty is in both Parkinson disease, rehabilitation, as well as pelvic health, and I always talked about the connections and wanting to bring that information to more people. So I wanted to plate all that information together in this great course.

I got started specializing in Parkinson's back in the early 2000s. I was hired at a hospital as an occupational therapist working with people with Parkinson disease. But when I was in college my real interest was pelvic health. So I kind of got thrown into learning a whole lot about Parkinson disease at that time and I got really interested in how it all related to what I really wanted to do, which was pelvic health. I was able to connect that all, really right from the beginning of my career. Even though I started more on the physical rehabilitation side of Parkinson disease, which I continue to this day. I am able to combine those two passions of mine.

I also am an instructor with LSVT Global(1)and so we do LSVT BIG®(2) course training and certification workshops and I work with them a lot. I also have still a physical rehab background, as well as my connection to the public health background, and I bring that all together in my course Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation. We have two packed-full days of information and I think really it does translate well to the virtual environment.

What are the connections between neuro and pelvic health? Can you talk about what some of the big cornerstone pieces are that you get to dive into with your class?

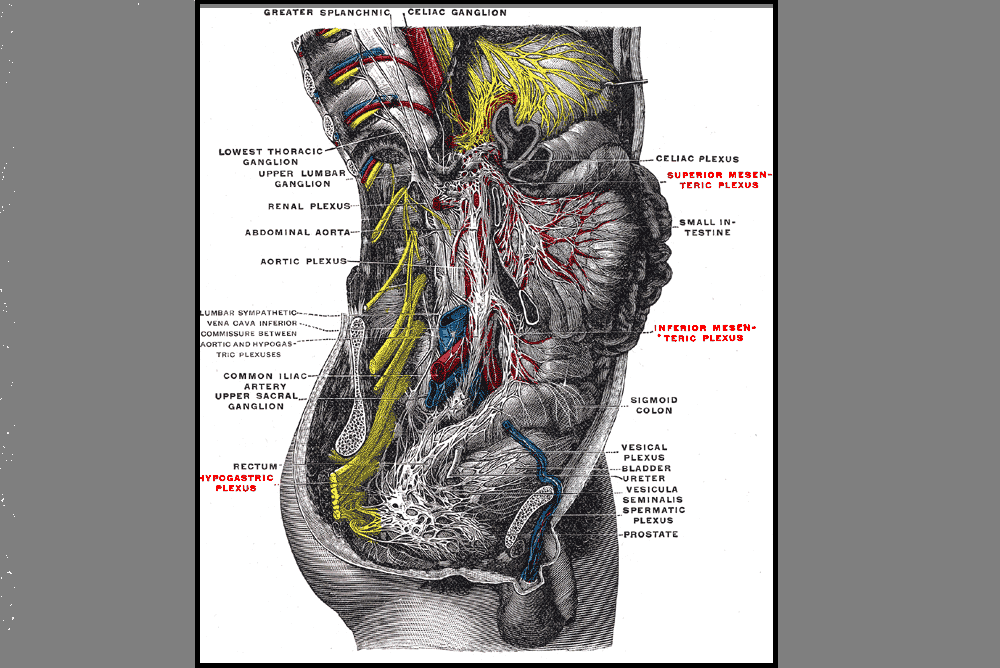

The beginning of the course on the first day is going back to the basics of neuro in general. Really getting our neuro brains on and thinking about terminology, topics related to neurotransmitters and the autonomic nervous system. Individuals with Parkinson’s specifically, their motor system is affected but also their non-motor systems. This includes autonomic function, the limbic system, and all of the different motor functions that also affect the pelvic floor in addition to all of the other muscles in the body.

We have all of this interplay of things going on that affect the bladder, bowel, and sexual health systems in individuals with Parkinson's that is a little bit different than your general population. There are a multitude of bladder issues that are very specific to the PD population, for example, overactive bladder.

This is just one example of the depths we go into right in the beginning on day one where we get into the neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of why that is actually happening. This then helps us go into day two where we talk about the practicality of what you do in the clinic about the things that are happening neurologically which is causing all of these bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues.

What kind of tools do you give to people to help practitioners understand and implement a treatment program?

People with PD are on very complex medication regimens and many of them are elderly, so the medication complexity is much more challenging in this population. At the end of day one, the last lecture, we go through the pharmacology very specifically for people with Parkinson’s in order to have a base of understanding of how that is interplaying with the pelvic health conditions.

We set the baseline of getting that information from your patient off the bat, then discuss what you want to be looking for when you start off with that patient and the importance of finding out what kind of bladder and bowel medications they have taken thus far and how that can potentially interplay with their Parkinson’s. Individuals with PD can have potentially worse side effects from some of those medications that are used for bladder issues specifically. We dig into what to look for, we talk a lot about practical behavioral modifications using bladder and bowel diaries and things like that to weed out some things in addition to using our other skills as pelvic health practitioners.

How can people prepare themselves to come to Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation, are there required readings or things that would be helpful for people to catch up a little bit on the pelvic health or neuro side?

I feel like, and I hope, that I did a really good job at the basic review right at the beginning so we can talk through these topics together. I prefer to take a course and not have to spend a lot of extra time on the pre-recordings because sometimes that can be overwhelming with busy lifestyles. When I put together this course I really wanted us to focus together as a group as we start the class to dig into those basics at the beginning and not have a lot of required things to do prior.

So what I did at the beginning of the course is to make a lot of tables, a lot of charts, and a lot of drawings, that we can reference (we don’t have to memorize it) and look at as needed. We can look at a chart and a drawing right next to it in the manual. I spent a lot of time just putting it all down in words, what I’m saying, so you don’t have to take a lot of notes. I think this has really helped practitioners as we get into the course and learn about the details of Parkinson’s and pelvic health.

What is it that makes you so passionate about working with these patients and continuing to learn and share your knowledge?

It is so heartwarming and feels so good to help these individuals. The motor symptoms of PD are really the ones recognized by physicians or even outwardly noticed even by other individuals. These private conditions of pelvic health that we are helping with are things that they might not even mention to their physician. Maybe we find out when we are doing other physical rehab or when colleagues refer them to us because they know what we do, and to help them with something of this magnitude that affects their everyday life - when they have trouble just walking, or moving or transferring.

Their caregiver burden for these individuals is so high because their loved one - now turned caregiver - is helping them do everything. We can make such an impact on these individuals. I mean, we do on other people too, but when you have a progressive neurologic condition and we can make an effect on shaping techniques they can use to improve their day-to-day. It’s just so great to be able to help them.

Sometimes these patients with PD can have cognitive impairments, they can have difficulties learning, and that can be helpful for the care partner. It can be a significant reduction in their burdon. I do talk a lot in the course about cognitive impairment and I give a lot of tips about how we can train and some ideas. People with Parkinson’s muscles and minds are a little different so there are some great tips that I can provide and lots of clinical experience.

I’ve been an occupational therapist for over 20 years, so I have a ton of clinical experience with this population. It’s been the population I’ve worked with my entire career. I hope I can provide the passion that I have for working with these individuals as well as the individuals who take my class.

I’m sure you would agree that we need more folks knowledgeable about Parkinson’s and combine that with pelvic health knowledge as well.

There are over a million people in the United States alone that have Parkinson disease. It’s the second most common neuro-degenerative disorder just behind Alzheimer’s disease. So there are so many individuals dealing with this and I think we can really expand our practices. I don’t think a lot of individuals that work in pelvic health market themselves to neurologists. There is an opening there for additional referrals and more people that we can help.

References:

- SVT Global is an organization that develops innovative treatments that improve the speech and movement of people with Parkinson’s disease and other neurological conditions. They train speech, physical and occupational therapists around the world in these treatments so that they can positively impact the lives of their patients.

- LSVT BIG®: Physical Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease and Similar Conditions. LSVT BIG trains people with Parkinson disease to use their body more normally.

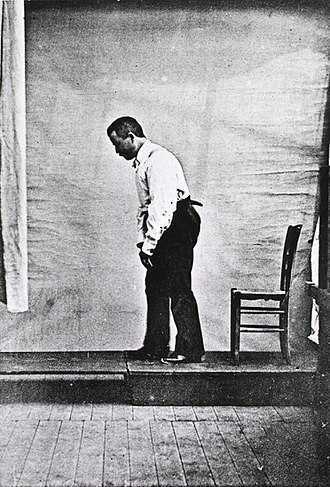

Parkinson disease is the second most common neurologic disorder. When most people think about people with Parkinson disease, they think about stooped posture, shuffling gait, slow and rigid movement, balance difficulties and tremoring. Often these motor symptoms are the main target of pharmacological treatments with neurologists and many experience positive functional gains. Non-motor symptoms, however, can be more disabling than the motor symptoms and have significant adverse effects on the quality of life in people with Parkinson disease.

Pelvic rehabilitation specialists have a unique opportunity to step in and help these individuals improve their quality of life and many neurologists are unaware of the benefits our services could provide for their patients.

Please join me in an exciting dive into understanding the physiology of how Parkinson disease affects a person’s pelvic health and develop your skills to effectively assess and develop treatment plans to change the life of these individuals.

Seppi, K., Ray Chaudhuri, K., Coelho, M., Fox, S. H., Katzenschlager, R., Perez Lloret, S., ... & Hametner, E. M. (2019). Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease—an evidence‐based medicine review. Movement Disorders, 34(2), 180-198.

If you work with orthopedic patients, I am sure that you have had a back-pain patient that you have discharged, only for them to return a year later suffering from another episode of pain. We all know that once someone suffers from a back injury, they are more likely to develop a chronic issue. Even patients with insidious back pain and no specific injury often develop chronic issues and can have pain that waxes and wanes after the initial episode.

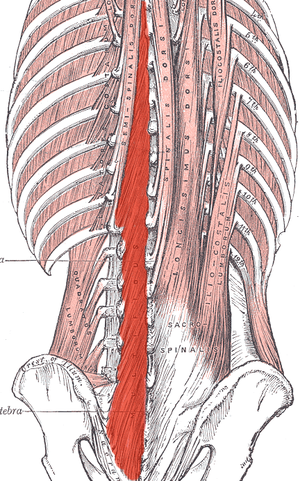

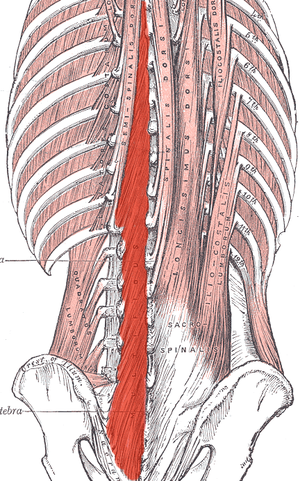

What happens in the body to cause this? Most of us have learned that the pelvic floor, transverse abdominus, and the deep fibers of the lumbar multifidus play an important role in stabilization. With injury, these muscles can become less effective in stabilizing the spine and pelvis. Studies have shown that muscle atrophy in the lumbar multifidus has been shown to occur with injuries and persist after resolution of the pain.1

What happens in the body to cause this? Most of us have learned that the pelvic floor, transverse abdominus, and the deep fibers of the lumbar multifidus play an important role in stabilization. With injury, these muscles can become less effective in stabilizing the spine and pelvis. Studies have shown that muscle atrophy in the lumbar multifidus has been shown to occur with injuries and persist after resolution of the pain.1

I recently did additional research to find out other reasons that cause these local stabilizing muscles to not function optimally. I found that these muscles also can suffer from arthrogenic muscle inhibition after an episode of low back pain.2 Arthogenic inhibition is a deficit in neural activation to a muscle. It is thought to occur due to a change in the discharge of articular sensory receptors due to swelling, inflammation, joint laxity, and damage to afferent nerves.2 EMG studies have shown reduced neural activity in the deeper fibers of the multifidus in patients with back pain.3

Another thing that fascinated me was that cortical changes in the brain also occur with low back pain. Changes in cortical representation of the multifidus and the body’s ability to voluntarily activate the muscle has been noted.4 Motor retraining has been shown to reorganize the motor cortex with regards to the transverse abdominus.5 Also, improvement in brain organization and function occurs after resolution of back pain.6

This is good news for patients! As therapists, we may not be able to do anything with respects to arthogenic inhibition. However, we can work on motor retraining for the core muscles. It has been shown that specific training that targets the multifidus can restore the neural activity to the multifidus and lead to improvement of pain and function.7,8 Training the multifidus can be difficult for therapists to teach. However, studies have found that ultrasound guided biofeedback is helpful for patients to learn to contract their multifidus.9,10

Come learn more about the multifidus and how it relates to back pain and stability. In Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging: Women's Health and Orthopedic Topics we will go over how to help your patients learn to activate and strengthen their multifidus. Join me on February 28 - March 1st in Raleigh, NC to learn new ways to help your patients!

1. Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Multifidus muscle recovery is not automatic after resolution of acute, first‐episode low back pain. Spine 1996;21:2763–2769.

2. Russo M, Deckers K, Eldabe S, et al. Muscle control and non-specific chronic low back pain. Neuromodulation: Technology at the neural interface. 2018; 21 (1): 1-9.

3. D'Hooge R, Hodges P, Tsao H, Hall L, Macdonald D, Danneels L. Altered trunk muscle coordination during rapid trunk flexion in people in remission of recurrent low back pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2013;23:173–181

4. Massé‐Alarie H, Beaulieu L‐D, Preuss R, Schneider C. Corticomotor control of lumbar multifidus muscles is impaired in chronic low back pain: concurrent evidence from ultrasound imaging and double‐pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. Exp Brain Res 2015; 234:1033–1045.

5. Tsao H, Galea MP, Hodges PW. Driving plasticity in the motor cortex in recurrent low back pain. Eur J Pain 2010;14:832–839.

6. Seminowicz DA, Wideman TH, Naso L et al. Effective treatment of chronic low back pain in humans reverses abnormal brain anatomy and function. J Neurosci 2011;31:7540–7550

7. França FR, Burke TN, Caffaro RR, Ramos LA, Marques AP. Effects of muscular stretching and segmental stabilization on functional disability and pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012;35:279–285.

8. Goldby LJ, Moore AP, Doust J, Trew ME. A randomized controlled trial investigating the efficiency of musculoskeletal physiotherapy on chronic low back disorder. Spine. 2006;31:1083–1093.

9. Ghamkhar L, Emami M, Mohseni‐Bandpei MA, Behtash H. Application of rehabilitative ultrasound in the assessment of low back pain: a literature review. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2011;15:465–477.

10. Van K, Hides JA, Richardson CA. The use of real‐time ultrasound imaging for biofeedback of lumbar multifidus muscle contraction in healthy subjects. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36:920–925

Pain demands an answer. Treating persistent pain is a challenge for everyone; providers and patients. Pain neuroscience has changed drastically since I was in physical therapy school. This update comes from the International Spine and Pain Institute headed by the lead author Adriaan Louw, PT, PhD. If you are interested in reading more about persistent pain, I suggest reading the article in its entirety.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

Pain neuroscience education is a way to explain pain to patients, often with analogies, with a focus on neurobiology and neurophysiology as it relates to that individuals pain experience. To be able to educate our patients, we as providers, must be able to understand neuromatrix, output, and threat. Moseley states “[p]ain is a multiple system output activated by an individual’s specific pain neuromatrix. The neuromatrix is activated whenever the brain perceives a threat”. If that sounds like gibberish, consider watching this TEDx talk by Lorimer Moseley on YouTube (the snake bite story is a favorite of mine):

What is a neuromatrix? Essentially, it is a pain map in the brain; a network of neurons spread throughout the brain, none of which deal specifically with pain processing. The way I visualize it is to think about what goes on when you think of your grandmother. There isn’t a grandmother center in the brain, but there are sights and smells (sensory), feelings (emotional awareness), and memories that all come up when you think about her. When we are overwhelmed with pain, those regions become taxed and the individual may have difficulty concentrating, sleeping, and/or may lose his/her temper more easily. Just as each person’s grandmother is different so is a person’s pain and the neuromatrix is affected by past experiences and beliefs.

Pain is an output. It is a response to a threat. When a person is exposed to a threatening situation, biological systems like the sympathetic nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, gastrointestinal system, and motor response system are activated. When a stress response occurs, these systems are either heightened or suppressed to help cope, thanks to the chemicals epinephrine and cortisol.

What is a threat? Threats can take a variety of forms; accidents, falls, diseases, surgeries, emotional trauma, etc. Tissues are influenced by how the individual thinks and feels, in addition to social and environmental factors. The authors propose that when individuals live with chronic pain, their body reacts as though they are under a constant threat. With this constant threat the system reacts and continues to react, and the nervous system is not allowed to return to baseline levels. This can create a patient presentation with immunodeficiency, GI sensitivity, poor motor control, and more. This sounds like most patients who walk into my clinic. The authors suggest that one system may be affected more and that can influence what the patient is diagnosed with even though the underlying biology is the same for many conditions. There are theories for why that happens; genetics, biological memory, or it could be the lens of the provider that the patient sees. There is a table in the article that shows symptoms, diagnosis, and current best evidence treatment for the conditions of fybromyalgia, chronic fatique syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease which is worth a look. The treatments all work to calm the central nervous system.

The authors go on to question the relationship between thyroid function and these conditions as changes in cortisol and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is fascinating, and confusing. Luckily, the Pelvic Floor Series Capstone course does a great job breaking it down.

Now that this hypothetical patient is in our treatment room what do we do? The authors suggest seeing these conditions for what they are: chronic pain conditions. They recommend that physical therapists see past the label that a patient may have picked up with a previous diagnosis, and keep the following in mind when treating these patients:

- They are hurting

- They are tired

- They may have lost hope

- They may be disillusioned by the medical community

- They need help

These people need the following from their medical providers:

- Compassion

- Dignity

- Respect

With empathy and understanding therapists can use skills in education, exercise and movement with the intent to improve system function (immune, neural, and endocrine), rather than fixing isolated mechanical deficits.

Louw, Adriaan PT, PhD; Schmidt, Stephen PT ; Zimney, Kory PT, DPT ; Puentedura, Emilio J. PT, DPT, PhD Treat the Patient, Not the Label: A Pain Neuroscience Update.[Editorial] Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 43(2):89-97, April/June 2019.

Most people are told that inguinal hernia repair is a low risk surgery. While death or severe injury is rare, penile or testes pain after hernia repair is not a novel or recent finding. In 1943, Magee first discussed patients having genitofemoral neuralgia after appendix surgery. By 1945, both Magee and Lyons stated that surgical neurolysis gave relief of genital pain following surgical injury (neurolysis is a surgical cutting of the nerve to stop all function). However, it should be noted that with neurolysis, sensory loss will also occur, which is an undesired symptom for sexual function and pleasure. In 1978 Sunderland stated genitofemoral neuralgia was a well-documented chronic condition after inguinal hernia repair.

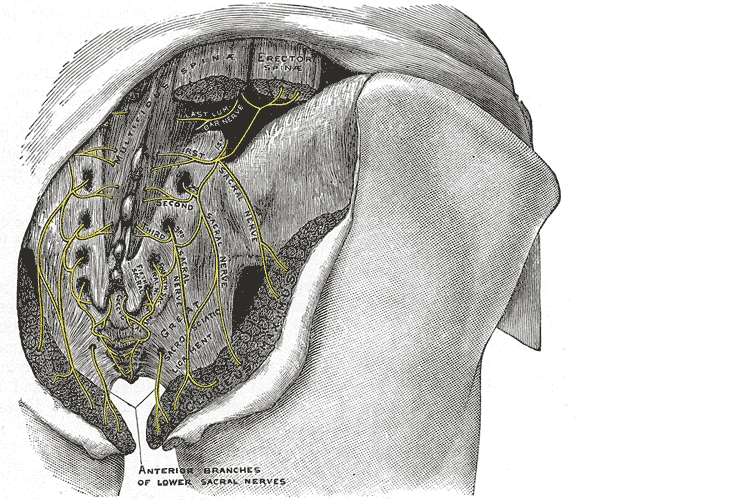

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

In 1999 Stark et al noted pain reports as high as 63% post hernia repair. The highest rates of genitofemoral neuralgia are reported with laparoscopic or open hernia repair (Pencina, 2001). The mechanism for GF neural entrapment is entrapment within scar or fibrous adhesions and parasthesia along the genitofemoral nerve (Harms 1984, Starling and Harms 1989, Murovic 2005, and Ducic 2008). It is well known that scar and adhesion densify and visceral adhesions increase for years after surgery. Thus, symptoms can increase long after the surgery or may take years to develop. In 2006, Brara postulated that mesh in the region can contribute to subsequent genitofemoral nerve tethering which can be exacerbated by mesh in the inguinal or the retroperitoneal space. With an anterior mesh placement, there is no fascial protection left for the genitofemoral nerve.

Genitofemoral neuralgia is predominately reported as a result of iatrogenic nerve damage during surgery or trauma to the inguinal and femoral regions (Murovic et al, 2005). However, genitofemoral neuropathy can be difficulty and elusive to diagnose due to overlap with other inguinal nerves (Harms, 1984 and Chen 2011).

In my clinical experience, I have seen such symptoms after hernia repair, but also after procedures near the inguinal region such as femoral catheters for heart procedures, appendectomies, and occasionally after vasectomy.

As a pelvic PT, what are we to do with this information? First off, we can realize that all pelvic neuropathy is not necessarily due to the pudendal nerve. In the anterior pelvis, there is dual innervation from the inguinal nerves off the lumbar plexus as well as the dorsal branch of the pudendal nerve. When patients have a history of inguinal hernia repair, we can consider the genitofemoral nerve as a source of pain. Medicinally, the only research validated options for treatment are meds such as Lyrica or Gabapentin that come with drowsiness, dizziness and a score of side effects. Surgically neurectomy or neural ablation are options with numbness resulting, however, many patients do not want repeated surgery or numbness of the genitals. As pelvic therapists, we can manually fascially clear the path of the nerve from L1/L2, through the psoas, into and out of the canal and into the genitals. We can also manually directly mobilize the nerve at key points of contact as well as doing pain free sliders and gliders and then give the patient a home program to maintain mobility. Pelvic manual therapy can offer a low risk, side-effect free option to ameliorate the sequella of inguinal hernia repair. Come join us at Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment in Chicago this Spring to learn how to effectively treat all the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Cesmebasi, A., Yadav, A., Gielecki, J., Tubbs, R. S., & Loukas, M. (2015). Genitofemoral neuralgia: a review. Clinical Anatomy, 28(1), 128-135.

Lyon, E. K. (1945). Genitofemoral causalgia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 53(3), 213.

Magee, R. K. (1943). Genitofemoral Causalgia: New Syndrome. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 98(3), 311.

Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1978

For many of our patients, chronic pain is a chronic stress. Unfortunately, the resulting ongoing physiological stress reaction can have neurotoxic influences in key brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus, and drive maladaptive neuroplastic changes that may further fuel a chronic pain condition.1 For example, chronic stress generates extensive dendritic spine loss in the prefrontal cortex, hyperactivity in the amygdala, and neurogenesis suppression in the hippocampus.2,3,4 In parallel, patients with chronic pain have been shown to exhibit reduced gray matter in the prefrontal cortex, increased neuronal excitability in the amygdala and reduced hippocampal neurogenesis.5,6,7

These three brain areas have been identified to play an important role in fear learning and memory.8 Modulated by stress hormones and stress-induced neuroplastic changes, stress may:

(a) enhance the memory of the initial pain experience at pain onset

(b) promote the later persistence of the pain memory

(c) impair the memory extinction process and the ability to establish a new memory trace.9

In other words, an ongoing stress reaction, triggered by distressing cognitions and emotions in response to pain or other life circumstances, could reinforce and strengthen the memory of pain. The experience of pain could be generated not by nociceptive activity, but by a well-established memory of pain and inability of the brain to create new associations. Leading researchers in the cortical dynamics of pain at Northwestern University suggest this learning process and persistence of pain memory could be a major influencing mechanism driving chronic pain.9,10

In other words, an ongoing stress reaction, triggered by distressing cognitions and emotions in response to pain or other life circumstances, could reinforce and strengthen the memory of pain. The experience of pain could be generated not by nociceptive activity, but by a well-established memory of pain and inability of the brain to create new associations. Leading researchers in the cortical dynamics of pain at Northwestern University suggest this learning process and persistence of pain memory could be a major influencing mechanism driving chronic pain.9,10

In addition, neurogenesis suppression in the hippocampus is associated with depression, while increased amygdala excitability is associated with anxiety, two mood disorders that frequently accompany and complicate chronic pain conditions.11,12

Why is this important? Appreciating the complex factors that contribute to chronic pain conditions can point to treatment strategies that address these factors.13 For example, strategies that help reduce a patient’s stress reaction, mitigate the experience of fear and anxiety, and/or promote relaxation, positive mood and self-efficacy could conceivably reduce the stress reaction and reverse maladaptive neuroplasticity. While chronic pain is a multifaceted and highly complex condition with no simple answers or one-size-fits-all successful treatment strategy, initial research suggests promise for this approach to modulate cortical structure. In a study of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in the treatment of chronic pain, an 11-week CBT treatment course increased gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.14

In addition, a systematic review of brain changes in adults who participated in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction identified increased activity, connectivity and volume in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in stressed, anxious and healthy adults.15 Also, the amygdala demonstrated decreased activity and improved functional connectivity with the prefrontal cortex. Although yet to be studied in patients with chronic pain, these neuroplastic changes could potentially promote improved cortical dynamics in our patients.

I am excited to share this model of chronic stress and chronic pain and evidence-based applications of mindfulness to pain treatment in my upcoming course Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment in Arlington, VA August 4 and 5, 2018 and in Seattle, WA November 3 and 4, 2018. Course participants will learn about mindfulness and pain research, practice mindful breathing, body scan and movement and expand their pain treatment tool box with practical strategies to improve pain treatment outcomes. Research examining the application of mindfulness in the treatment of patients at risk of opioid misuse will be included. I hope you will join me!

Vachon-Presseau E. Effects of stress on the corticolimbic system: implications for chronic pain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017; Oct 25. pii: S0278-5846(17)30598-5.

Arnsten AF. Stress signaling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009:10(6):410-422.

Zhang X, Tong G, Guanghao Y, et al. Stress-induced functional alterations in amygdala: implications for neuropsychiatric diseases. Front Neurosci. 2018 May 29;12:367.

Kim EJ, Pellman B, Kim JJ. Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review. Learn Mem. 2015;22(9):411-6.

Fritz HC, McAuley JH, Whittfeld K, et al. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and anterior insular gray matter: results from a population-based cohort study. J Pain. 2016;17(1):111-8.

Veinante P, Yalcin I, Barrot M. The amygdala between sensation and affect: a role in pain. J Mol Psychiatry. 2013;1(1):9.

Vachon-Presseau E. Roy M, Martel MO, et al. The stress model of chronic pain: evidence from basal cortisol and hippocampal structure and function. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 3):815-27.

Greco JA, Liberzon I. Neuroimaging of fear-associated learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(1):320-334.

Mansour AR, Farmer MA, Baliki. Chronic pain: role of learning and brain plasticity. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2014;32(1):129.

Baliki MN, Apkarian AV. Nociception, pain, negative moods and behavior. Neuron. 2015;87(3):474-491.

Schmaal L, Veltman DJ, van Erp TG, et al. Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from ENIGMA major depressive disorder working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):806-12.

Shin LM, Liberzon I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):169-91.

Greenwald J, Shafritz KM. An integrative neuroscience framework for the treatment of chronic pain: from cellular alterations to behavior. Front Int Neurosci. 2018 May 23;12:18.

Seminowicz DA, Shpaner M, Keaser ML, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy increases prefrontal cortex gray matter in patients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2013;14(2):1573-84.

Gotink RA, Meijboom R, Vernooij, et al. 8-week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction induces brain changes similar to traditional long-term meditation practice – A systematic review. Brain Cogn. 2016;108:32-41.

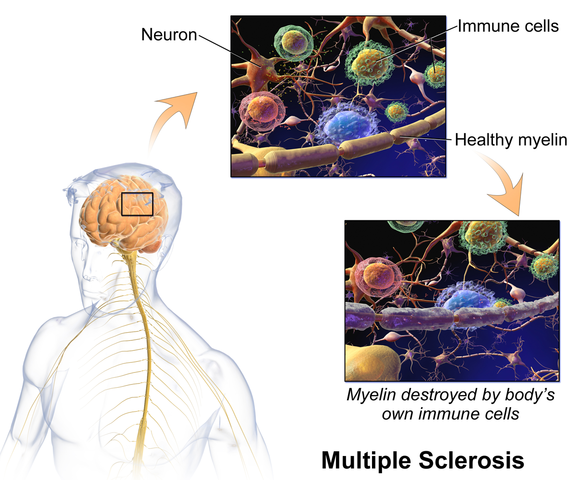

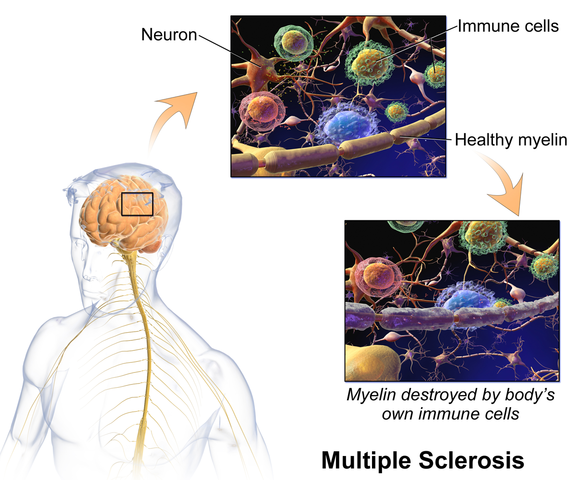

The British author, John Donne, wrote, “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent.” In a similar idea, no neurological symptom is independent and isolated; every system has potential to impact the whole body. Neurogenic bladder should cue a clinician to check for neurogenic bowel and to assess the pelvic floor in order to get a complete map of what to address in treatment.

Martinez, Neshatian, & Khavari (2016) reviewed literature on neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) and neurogenic bladder in patients with neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS). Constipation and fecal incontinence can coexist with NBD, and a multifactorial bowel regimen is vital to conservative management in patients with neurological disorders. Nonpharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical approaches were reviewed in the article. Specific results for MS were reported only for transanal irrigation (TAI) and biofeedback. In TAI, fluid is used to stimulate the bowel and clean out stool from the rectum. A study showed 53% of the 30 patients with MS demonstrated a 50% or better improvement in bowel symptoms with TAI. In anorectal biofeedback, operant conditioning retrains motor and sensory responses via exercises guided by manometry. With biofeedback, a study showed 38% of patients had a beneficial impact with the intervention. The list of treatment approaches not specifically researched for MS patients in this review includes: dietary modifications, perianal/anorectal stimulation, abdominal massage, suppositories, oral medications such as stool softeners or prokinetic agents, sacral neuromodulation, antegrade continence enema, and colostomy.

Martinez, Neshatian, & Khavari (2016) reviewed literature on neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) and neurogenic bladder in patients with neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS). Constipation and fecal incontinence can coexist with NBD, and a multifactorial bowel regimen is vital to conservative management in patients with neurological disorders. Nonpharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical approaches were reviewed in the article. Specific results for MS were reported only for transanal irrigation (TAI) and biofeedback. In TAI, fluid is used to stimulate the bowel and clean out stool from the rectum. A study showed 53% of the 30 patients with MS demonstrated a 50% or better improvement in bowel symptoms with TAI. In anorectal biofeedback, operant conditioning retrains motor and sensory responses via exercises guided by manometry. With biofeedback, a study showed 38% of patients had a beneficial impact with the intervention. The list of treatment approaches not specifically researched for MS patients in this review includes: dietary modifications, perianal/anorectal stimulation, abdominal massage, suppositories, oral medications such as stool softeners or prokinetic agents, sacral neuromodulation, antegrade continence enema, and colostomy.

Miletta, Bogliatto, & Bacchio (2017) presented a case study about management of sexual dysfunction, perineal pain, and elimination dysfunction in a 40 year old female with multiple sclerosis. She had been experiencing perineal pain for 5 months and had chronic MS symptoms of lower anourogenital dysfunction, including bladder retention and obstructed defecation syndrome. Physical therapy treatment included pelvic floor muscle training (primarily decreasing overactivity of pelvic muscles in this case), perineal massage, biofeedback, postural correction, global relaxation techniques, and a home self-training program. After 5 months of physical therapy, the woman had improved pelvic floor muscle contraction strength, resolution of pelvic floor muscle overactivity, increased sexual satisfaction (according to the Female Sexual Function Index score), a visual analog scale improvement of vulvar and perineal pain by 4 points, normalization of obstructed defecation syndrome, and decreased bladder retention symptoms. The authors concluded the variety of symptoms in MS require a multimodal approach for treatment, considering all the motor, autonomic, and cognitive impairments as well as side effects of medications that try to improve those symptoms. The quality of life of women with MS has potential to be improved significantly if pelvic floor disorders related to MS are addressed appropriately.

Ultimately, treating urinary dysfunction but avoiding bowel dysfunction does neurological patients a disservice. Systems are intertwined in a series of cause and effects throughout the body. The “Neurologic Conditions and the Pelvic Floor” course can expand your knowledge and understanding of how the symptoms of conditions such as multiple sclerosis can impact pelvic health and how we can better address the whole patient for optimal outcomes.

Martinez, L., Neshatian, L., & Khavari, R. (2016). Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction in Patients with Neurogenic Bladder. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports, 11(4), 334–340. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11884-016-0390-3

Miletta, M., Bogliatto, F., & Bacchio, L. (2017). Multidisciplinary Management of Sexual Dysfunction, Perineal Pain, and Elimination Dysfunction in a Woman with Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of MS Care, 19(1), 25–28. http://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2015-082

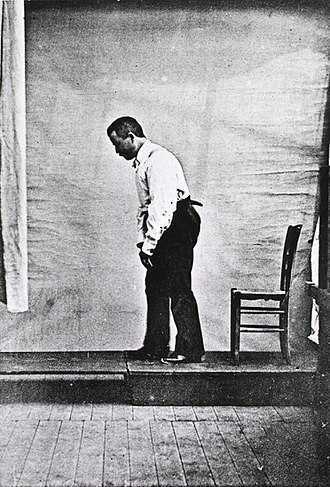

Akinesia is a term typically used to describe the movement dysfunction observed in people with Parkinson disease. It is defined as a poverty of movement, an impairment or loss of the power to move, and a slowness in movement initiation. There is an observable loss of facial expression, loss of associated nonverbal communicative movements, loss of arm swing with gait, and overall small amplitude movements throughout all skeletal muscles in the body. The cause of this characteristic profile of movement is due to loss of dopamine production in the brain which causes a lack of cortical stimulation for movement.

If the loss of dopamine production in the brain causes this poverty of movement in all skeletal muscles the body, how does the pelvic floor function in the person with Parkinson disease and what should the pelvic floor rehabilitation professional know about treating the pelvic floor in this population of patients?

If the loss of dopamine production in the brain causes this poverty of movement in all skeletal muscles the body, how does the pelvic floor function in the person with Parkinson disease and what should the pelvic floor rehabilitation professional know about treating the pelvic floor in this population of patients?

Let’s take a closer look referencing a very telling article about Parkinson disease and skeletal muscle function. In the Italian town of L’Aquila, a major devastating 6-point Richter scale earthquake occurred on April 6, 2009. 309 people died and there was destruction and collapse of many historical structures, some greater than 100 years old. The nearby movement disorder clinic had been following 31 Parkinson disease patients in the area, 17 of them higher functioning and the other 14 much lower functioning. In fact, of those 14, 10 of them were affected by severe freezing episodes with severe nighttime akinesia requiring assistance with bed mobility tasks, 1 was completely bedridden and the others with major fluctuations in motor performance. 13 of the 14 patients also had fluctuating cognitive functioning.

This devastating earthquake occurred at 3:30 am. All 14 of these patients were able to escape from their homes during or immediately following the event. Caregivers reported that in the majority of the cases, the person with Parkinson’s disease was the first one to be alerted to the earthquake, the first one to get out of the house, ability to alert relatives to run for safety, physically assisting relatives out of the collapsing buildings, and in some cases independently escaping down 1-2 flights of stairs.

Paradoxical kinesia is thought to be the reason for this all but sudden ability to move normally within the presence of an immediate threat to their life and lives of loved ones. Paradoxical kinesia is defined as “a sudden and brief period of mobility typically seen in response to emotional and physical stress in patient’s with advanced idiopathic Parkinson’s disease.” There are a few mechanisms hypothesized to play a role, such as, adrenaline, dopaminergic reserves activating the flight reaction, and compensatory nearby cerebellar circuitry.

There is no pathological evidence that in Parkinson disease there is any break in the continuity of the motor system. The neurologic pathways are all intact and the ability to produce muscle power is retained however requires a strong base of clinic knowledge of the disease to help these patients activate these intact motor pathways. I look forward to sharing the neurologic basis of these deficits in Parkinson disease and strategies in pelvic floor rehab to do just that!

Erica Vitek, a specialist in treating patients with neurologic dysfunction, is the author and instructor of Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab, taking place September 14-16, 2018 in Grand Rapids, MI.

Bonanni, L., Thomas, A., Anzellotti, F., Monaco, D., Ciccocioppo, F., Varanese, S., Bifolchetti, S., D’Amico, M.C., Di Iorio, A. & Onofrj, M. (2010). Protracted benefit from paradoxical kinesia in typical and atypical parkinsonisms. Neurological sciences, 31(6), 751-756.

The following is a guest submission from Alysson Striner, PT, DPT, PRPC. Dr. Striner became a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) in May of 2018. She specializes in pelvic rehabilitation, general outpatient orthopedics, and aquatics and treats at Carondelet St Joesph’s Hospital in the Speciality Rehab Clinic located in Tucson, Arizona.

Recently, I had a patient present with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) on his right foot. He stated that the pain had started about 10 days after his prostatectomy when someone had fallen onto his right foot. He reported a bunionectomy on that foot 7 years prior and noted an episode of plantar facilities before his prostatectomy. CRPS is defined as “chronic neurologic condition involving the limbs characterized by severe pain along with sensory, autonomic, motor, and trophic impairments” in a 2017 article "Complex regional pain syndrome; a recent update" by Goh, En Lin. The article goes on to discuss how CRPS can set off a cascade of problems including altered cutaneous innervation, central and peripheral sensitization, altered sympathetic nervous system function, circulating catecholamines, changes in autoimmunity, and neuroplasticity.

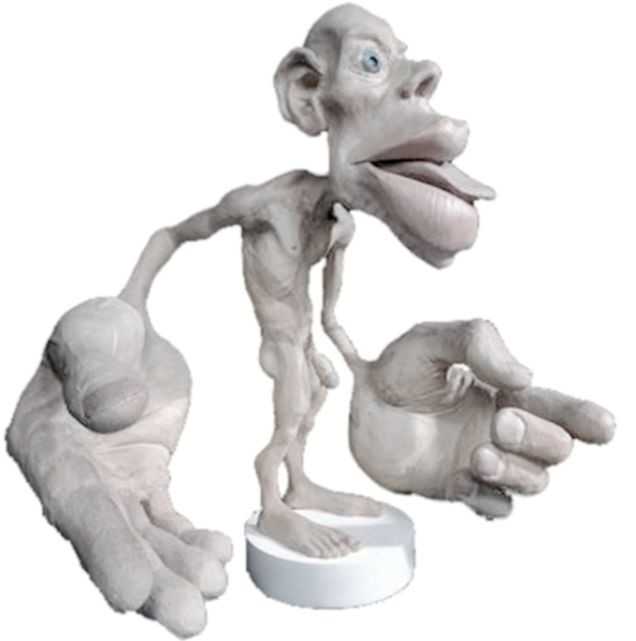

A recent persistent pain theory to explain the relationship between pelvic floor and his foot could be overflow or ‘smudging’ in his homunculus. The homunculus is the map of our physical body in our brain where the feet are located next to the genitals. Possibly when one has pain, there can be ‘smudging’ of our mental body map from one area into another. I have heard this explained as though a chalk or charcoal drawing has been swipes their hand through the picture. A recent study by Schrabrun, SM et al “Smudging of the Motor Cortex is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain” found that people with chronic low back pain had a loss of cortical organization which and that this loss was associated with the severity and location of LBP.

A recent persistent pain theory to explain the relationship between pelvic floor and his foot could be overflow or ‘smudging’ in his homunculus. The homunculus is the map of our physical body in our brain where the feet are located next to the genitals. Possibly when one has pain, there can be ‘smudging’ of our mental body map from one area into another. I have heard this explained as though a chalk or charcoal drawing has been swipes their hand through the picture. A recent study by Schrabrun, SM et al “Smudging of the Motor Cortex is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain” found that people with chronic low back pain had a loss of cortical organization which and that this loss was associated with the severity and location of LBP.

There are many ways to improve the organization of the homunculus and create neuroplasticity. One such way was suggested is with Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) to the bottom of the foot to affect bladder spasms and pain. In recent study, “Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of somatic afferent nerves of the foot relieved symptoms related to postoperative bladder spasms,". Zhang, C et al. 2017 found that participates that had either a bladder surgery or a prostate surgery had improvement in bladder spasm symptoms and VAS scores on day two and three. Their protocol was to use two electrodes over the bottom of the foot at 5 Hz with 0.2 millisecond pulse width until a muscle twitch was achieved and was increased, but still comfortable for an hour (there is a picture of electrode placement in the article). The authors note that this neuromodulation of the foot sensory nerves may inhibit interactions between the somatic peripheral neuropathway and autonomic micturition reflex to calm the bladder and pain.

No matter what we do to help calm nervous systems from the top down; pain neuroscience education, mindful based relaxation, graded motor imagery, or from the bottom up; de-sensitization, biofeedback, or good old-fashioned TENS. The result is the same; a cortical organization and happier patients.

En Lin Goh†, Swathikan Chidambaram† and Daqing Ma. "Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update". Burns & Trauma 2017 5:2.https://doi.org/10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4"

Schabrun SM, Elgueta-Cancino EL, Hodges PW. "Smudging of the Motor Cortex Is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain." Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017 Aug 1;42(15):1172-1178. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000938

Chanjuan Zhang, et al. "Transcutaneous electrical stimulation of somatic afferent nerves in the foot relieved symptoms related to postoperative bladder spasms". BMC Urol. 2017; 17: 58. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0248-9

Neurophysiology is a dynamic and highly complex system of neurological connections and interactions that allow for bodily performance. When all of those connections are working correctly, our bodies can function at optimal levels. When there is a break or injury to those connections, dysfunction results but amazingly in some circumstances, our bodies have work arounds to allow for certain functions to continue working.

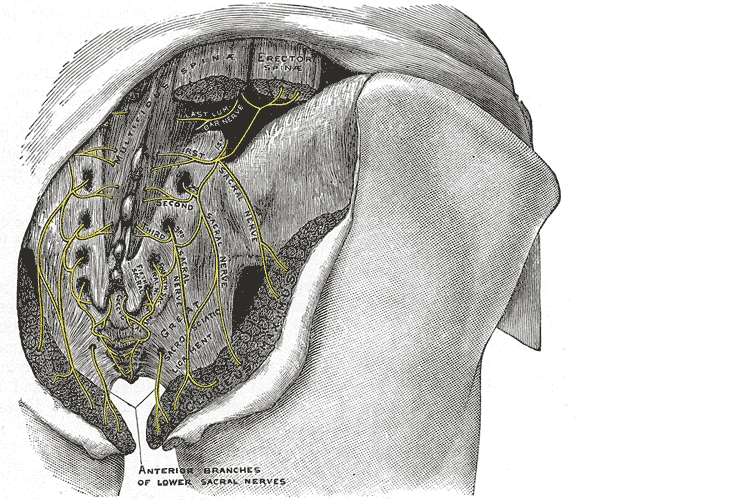

If we take the sexual neural control system of the male, for instance, a perfect example of this can be described. Many men were injured fighting in World War II. During their time in battle, many experienced spinal cord injuries. Some of these injuries were severe resulting in complete spinal cord damage at level of injury. A physician, Herbert Talbot, in 1949, documented his examination of 200 men with paraplegia. Two thirds of the men were surprisingly able to achieve erections and some were able to experience vaginal penetration and orgasm. Much of their basic functionality had been lost however amazingly there was preservation of erectile function.

The reason these men with paraplegia were able to maintain erectile or orgasm functionality is due to the physiological function in the sacral spinal cord. A reflex arc is present in this region. The definition of a reflex arc is a nerve pathway that has a reflexive action involving sensory input from a peripheral somatic or autonomic nerve synapsing to a relay neuron or interneuron in the sacral cord segment then synapsing to a motor nerve for output to the muscular region. These messages do not need to travel up the spinal cord to the brain in order to be activated. Instead they work within a ‘loop’ at the sacral spinal cord level. In the case of spinal cord injury, erectile function as well as other functions controlled by reflex arcs, can be preserved.

For women, the same is true. In order for a female to have engorgement of the clitoris or orgasm, the sacral spinal reflex arc needs to be intact. If a woman experiences a spinal cord injury above the sacral region, the ability to have a reflexive orgasm within the sacral spinal reflex arc will remain.

The sacral reflex arc also plays an important role in activation of the pelvic floor muscles during the sexual response cycle. During genital stimulation in both the male and female, the bulbospongiosus or bulbocavernosus begins to activate in a reflexive pattern to hinder the outflow of blood from the region which facilitates erectile tissue of the penis and clitoris to become erect. This can then be followed by rhythmic reflexive contractions of the pelvic floor musculature during orgasm.

To learn more about the implications that neurologic disorders can have on the sexual system, please join us for Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab, coming to Grand Rapids, MI in September.

Goldstein, I. (2000). Male sexual circuitry. Scientific American, 283(2), 70-75.

Sipski, M. L. (2001). Sexual response in women with spinal cord injury: neurologic pathways and recommendations for the use of electrical stimulation. The journal of spinal cord medicine, 24(3), 155-158.

Wald, A. (2012). Neuromuscular Physiology of the Pelvic Floor. In Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (Fifth Edition)(pp. 1023-1040).