Today's guest post comes from Kelsea Cannon, PT, DPT, a pelvic health practitioner in Seattle, WA. Kelsea graduated from Des Moines University in 2010 and practices at Elizabeth Rogers Pilates and Physical Therapy.

Many studies done on pelvic floor muscle training largely have subjects who are Caucasian, moderately well educated, and receive one-on-one individualized care with consistent interventions. This led a group of researchers to investigate the occurrence of pelvic floor dysfunction, specifically pelvic organ prolapse (POP), in parous Nepali women. These women are known to have high incidences of POP and associated symptomology. Another impetus to perform this research: the discovery that there was a major lack of proper pelvic floor education for postpartum women. These women were commonly encouraged to engage their pelvic floor muscles via performing supine double leg lifts, sucking in their tummies/holding their breath/counting to ten, and squeezing their glutes. These exercises would be on a list of no-no’s here in the United States. In 2017, Delena Caagbay and her team of researchers discovered that in Nepal, no one really knew the correct way to teach proper pelvic floor muscle contractions, preventing the opportunity for women to better understand their pelvic floors. The team then set out to investigate the needs of this population, with the eventual goal of providing effective pelvic floor education for Nepali women.

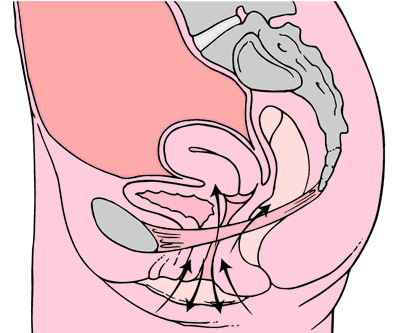

Caagbay and her team first wanted to know what baseline muscle activity the Nepali women had in their pelvic girdle. Physical examinations and internal pelvic floor muscle strength assessments revealed that surprisingly there was a low prevalence of pelvic floor muscle defects, such as levator avulsions and anal sphincter trauma. Uterine prolapses were most common while rectoceles were comparatively less common. Their muscles were also strong and well-functioning, often averaging a 3/5 on the Modified Oxford Scale. It was hypothesized that these women had low prevalence of muscle injury because instruments were not commonly used during childbirth, they had lower birth weight babies, and the women were typically younger when giving birth (closer to 20-21 years old). But they had a high prevalence of POP even with good muscle tone? Researchers suggested that their incidence of POP is likely stemming from their sociocultural lifestyle requirements, as women are left to do most of the daily household chores and caregiving tasks while men often travelled away from the home to perform paid labor. Physical responsibilities for these women commonly begin at younger ages and while it helps promote good muscle tone, the heavier loading places pressure on the connective tissue and fascia that support the pelvic organs. Because of the demands of their lifestyles, Nepali women are often forced to return to their physically active state within a couple weeks after giving birth.

Caagbay and her team first wanted to know what baseline muscle activity the Nepali women had in their pelvic girdle. Physical examinations and internal pelvic floor muscle strength assessments revealed that surprisingly there was a low prevalence of pelvic floor muscle defects, such as levator avulsions and anal sphincter trauma. Uterine prolapses were most common while rectoceles were comparatively less common. Their muscles were also strong and well-functioning, often averaging a 3/5 on the Modified Oxford Scale. It was hypothesized that these women had low prevalence of muscle injury because instruments were not commonly used during childbirth, they had lower birth weight babies, and the women were typically younger when giving birth (closer to 20-21 years old). But they had a high prevalence of POP even with good muscle tone? Researchers suggested that their incidence of POP is likely stemming from their sociocultural lifestyle requirements, as women are left to do most of the daily household chores and caregiving tasks while men often travelled away from the home to perform paid labor. Physical responsibilities for these women commonly begin at younger ages and while it helps promote good muscle tone, the heavier loading places pressure on the connective tissue and fascia that support the pelvic organs. Because of the demands of their lifestyles, Nepali women are often forced to return to their physically active state within a couple weeks after giving birth.

After assessing the current needs, cultural norms, and prevalence of POP in Nepali women, Caagbay et al created an illustrative pamphlet on how to contract pelvic floor muscles as well as provided verbal instruction on pelvic floor muscle activation. Transabdominal real time ultrasound was applied to assess the muscle contraction of 15 women after they received this education. Unfortunately, even after being taught how to engage their pelvic floor muscles, only 4 of 15 correctly contracted their pelvic floors.

This study highlighted that brief verbal instruction plus an illustrative pamphlet was not sufficient in teaching Nepali women how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles. Although there was a small sample size, these results can likely be extrapolated to the larger population. Further research is needed to determine how to effectively teach correct pelvic floor muscle awareness to women with low literacy and/or who reside in resource limited areas. Lastly, it is important to consider the significance of fascial and connective tissue integrity within the pelvic floor when addressing pelvic organ prolapse.

1 Can a leaflet with brief verbal instruction teach Napali women how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles? DM Caagbay, K Black, G Dangal, C Rayes-Greenow. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 15 (2), 105-109.

https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/JNHRC/article/viewFile/18160/14771

2 Pelvic Health Podcast. Lori Forner. Pelvic organ prolapse in Nepali women with Delena Caagbay. May 31, 2018.

3 The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse in a Nepali gynecology clinic. (2017) F. Turel, D. Caagbay, H.P. Dietz. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sydney Medical School Napean, University of Sydney.

4 The prevalence of major birth trauma in Nepali women. (2017) F. Turel, D. Caagbay, H.P. Dietz. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sydney Medical School Nepean, University of Sydney.

After completing an intake on a patient and learning that her history of constipation started about 3 years ago with insidious onset, the story wasn’t really making any sense of how or why this started. Yes, she was menopausal. Yes, she seemed to be eating fiber and drinking water. Yes, she got a bowel movement urge daily, but her bowel movements felt incomplete. Yes, she was a little older, using Estrace cream, and her mobility had slowed down, but nothing seemed to make sense in the story that was leading me to believe it was an emptying problem or a stool consistency issue. She had a bowel movement urge, she could empty, but it was incomplete.

So, after explaining about physical therapy, the muscle problems involved and what we do here, it led us to the physical examination portion. I explained that we check both the vaginal and rectal pelvic floor muscle compartments to determine rectal fullness internally, check for a rectocele, check for muscle lengthening (excursion) and shortening (contraction). She was on board and desperate to find an answer. She was eager for me to help her find an answer to her emptying problem that she had for the last 3 years.

So, after explaining about physical therapy, the muscle problems involved and what we do here, it led us to the physical examination portion. I explained that we check both the vaginal and rectal pelvic floor muscle compartments to determine rectal fullness internally, check for a rectocele, check for muscle lengthening (excursion) and shortening (contraction). She was on board and desperate to find an answer. She was eager for me to help her find an answer to her emptying problem that she had for the last 3 years.

Upon entering her vaginal canal slowly, I start to move around and felt a ring of plastic. “Are you wearing a pessary?” I asked. “Pessary? Oh, yes, I forgot to tell you about that!”, she exclaimed. “How long have you been using it?” I asked. “About 3 years…” she answered.

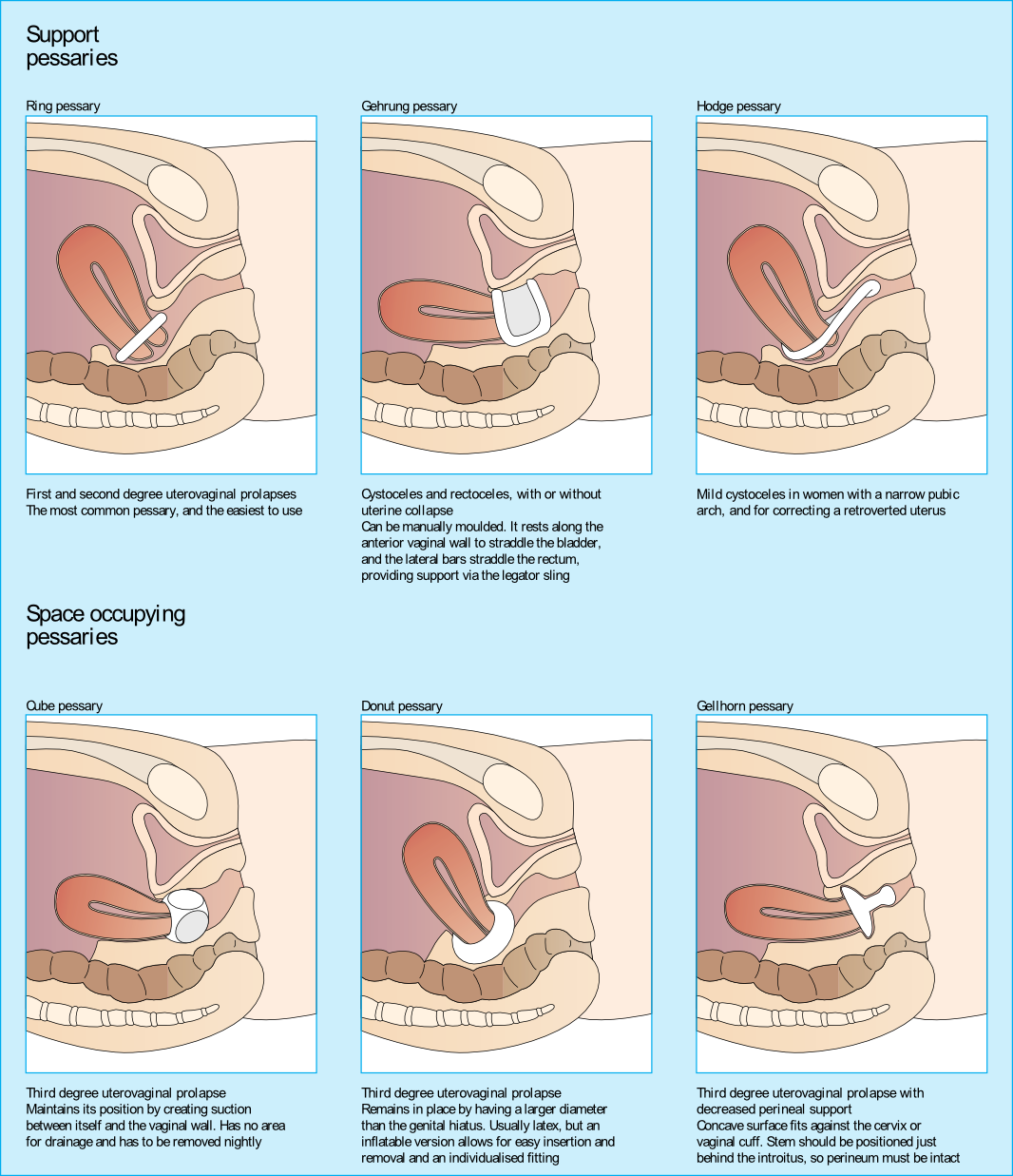

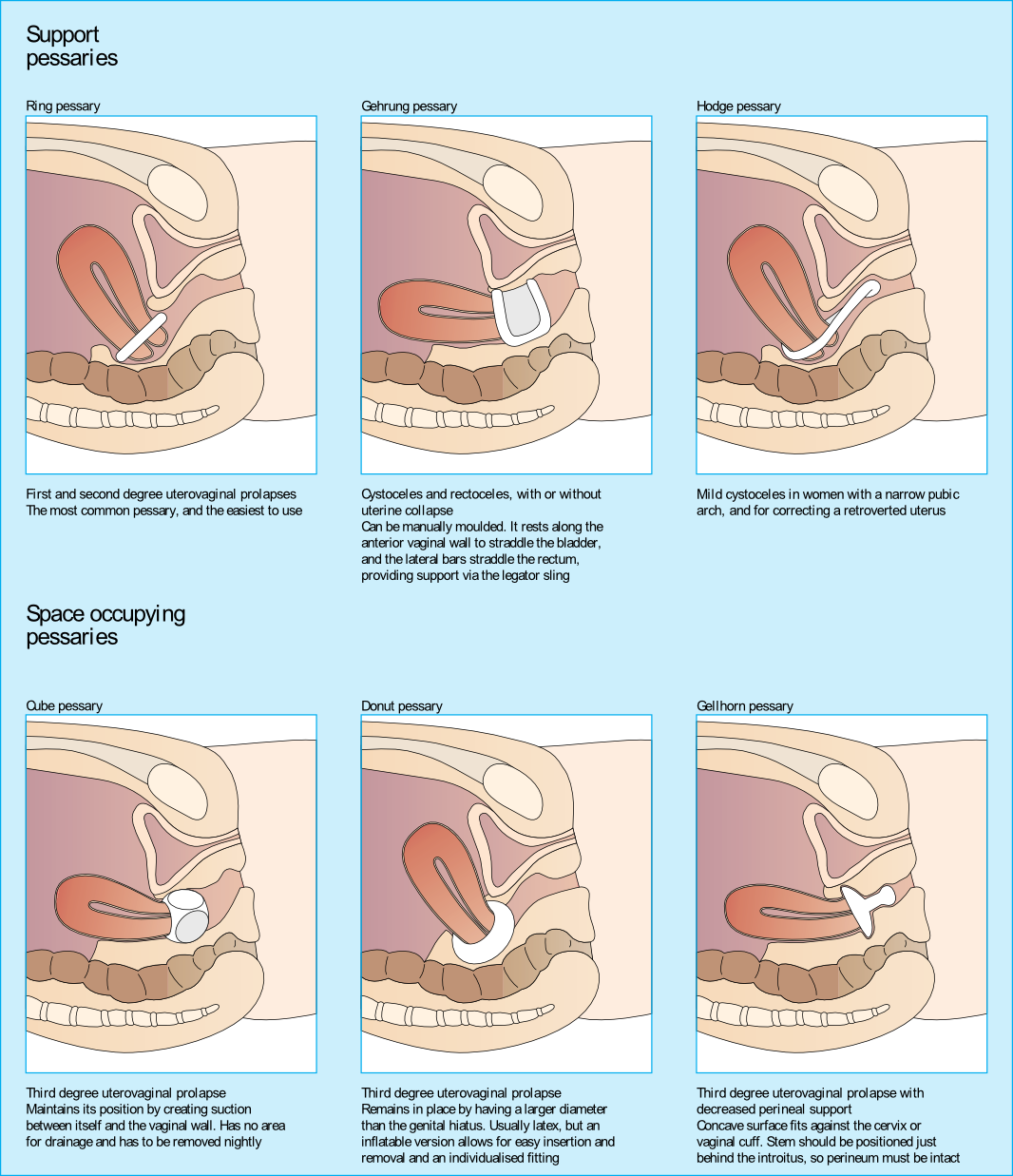

I sent her back to the urogynecologist to get fit for another type of pessary as her muscle examination proved to be negative. Since that time, I have added the question “Do you wear a pessary?” as part of the constipation intake questions. Pessary use creates the ability for a patient to forgo or to extend their time for a surgical intervention due to pelvic organ prolapse.

Looking at the dynamics of the pessary, it may block bowel movement emptying. The recent study by Dengle, et al, published in the October 2018 in the International Urogynecological Journal confirms this anecdotal, clinical finding. The article, Defecatory Dysfunction and Other Clinical Variables Are Predictors of Pessary Discontinuation, looked at reasons for discontinuation of pessary use from April 2014 to January 2017 and did a retrospective chart review on a selected 1071 women. Incomplete defecation had the largest association with pessary discontinuation.

While there are over 20 sizes of pessaries on the market, patients will discontinue use without having a better conversation with their practitioner. From a PT perspective, when the patient comes in with bowel emptying issues, if no muscle dysfunction is found, it needs to be brought to the provider’s attention. Our role in educating the patient on the options that are available and creating this dialogue can prove to be very helpful in those suffering from pelvic organ prolapse and defecatory dysfunction.

Dengler, EG et al. "Defecatory dysfunction and other clinical variables are predictors of pessary discontinuation." Int Urogynecol J. 2018 Oct 20. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3777-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30343377

Examples of pranayama

Ujjayi

Letting Go Breath

Integrating into the clinic

1) Iyengar BKS. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Schocken; 1995.

2) Sapsford RR, Richardson CA, Maher CF, Hodges PW. Pelvic floor muscle activity in different sitting postures in continent and incontinent women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(9):1741-1747.15.

3) Julie Wiebe, Physical Therapist | Educator, Advocate, Clinician. 2015; http://www.juliewiebept.

4) Talasz H, Kremser C, Kofler M, Kalchschmid E, Lechleitner M, Rudisch A. Phase-locked parallel movement of diaphragm and pelvic floor during breathing and coughing-a dynamic MRI investigation in healthy females. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(1):61-68.

5) Sapsford R. Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Man Ther. 2004;9(1):3-12.

6) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

7) Massery M. THE LINDA CRANE MEMORIAL LECTURE: The Patient Puzzle: Piecing it Together. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2009;20(2):19-27.

8) Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle: An integration of clinical expertise and research, 4e. Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

What's the evidence, and what's the answer?

In getting ready to teach my Menopause course in Minneapolis next month, I always like to do a review of the evidence, to see what’s new, or what’s changed. What has changed over the past few years – more and more evidence to support the role of skilled rehab providers, using evidence based assessment techniques to gauge the grade of pelvic organ prolapse and assess the risk of levator avulsion. What hasn’t changed enough – the level of awareness of the benefits of pelvic rehab in managing, or in some cases even reversing, the effects and symptoms of prolapse.

Dr Peter Dietz, from the University of Sydney, writes ‘…although clinical anecdote suggests some physiotherapists recognize other characteristics suggesting muscle dysfunction (e.g. holes, gaps, ridges, scarring) or pelvic floor dysfunction (e.g. width between medial edges of pelvic floor muscle) with palpation it is difficult to find any literature describing the techniques needed to do this or their accuracy or repeatability. Mantle (in 2004) noted that with training and experience a physiotherapist might be able to discern muscle integrity, scarring, and the width between the medial borders of the pelvic floor muscles, with palpation. It is not clear to what extent physiotherapists are able to do this reliably or how such characteristics are to be recorded.’

Dr Peter Dietz, from the University of Sydney, writes ‘…although clinical anecdote suggests some physiotherapists recognize other characteristics suggesting muscle dysfunction (e.g. holes, gaps, ridges, scarring) or pelvic floor dysfunction (e.g. width between medial edges of pelvic floor muscle) with palpation it is difficult to find any literature describing the techniques needed to do this or their accuracy or repeatability. Mantle (in 2004) noted that with training and experience a physiotherapist might be able to discern muscle integrity, scarring, and the width between the medial borders of the pelvic floor muscles, with palpation. It is not clear to what extent physiotherapists are able to do this reliably or how such characteristics are to be recorded.’

Dr Dietz describes a palpation technique to assess the integrity of the pubovisceral muscle insertion, by checking the gap between the urethra centrally and the pubovisceral muscle laterally. On levator contraction this gap should be little wider than your index finger, otherwise an avulsion injury is very likely.

There is another aspect of levator assessment that can yield important information on clinical examination. The size of the levator hiatus can be estimated by determining the sum of the genital hiatus (gh) and perineal body (pb) in the context of the ICS POP-Q examination. Gh + pb, ie., the distance between the external urethral meatus and the centre of the anus, when measured on maximal Valsalva with a simple ruler, is highly predictive of symptoms and signs of prolapse, and it is very strongly correlated with hiatal area on Valsalva (Khunda et al., 2011).

Using this research, in the lab sessions of the Menopause course, we will review these palpation and measurement skills to give therapists the skills they need to confidently assess risk of levator avulsion and its impact on pelvic organ prolapse, and to use this information to devise a functionally appropriate rehab program.

Come and join the conversation in my course, Menopause Rehabilitation and Symptom Management!

Khunda A1, Shek KL, Dietz HP., Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;206(3):246.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.876. Epub 2011 Nov 7. Can ballooning of the levator hiatus be determined clinically?

The following comes to us from Felicia Mohr, DPT, a guest contributor to the Pelvic Rehab Report.

Vaginal mesh kits were used frequently early in the millennium as they led to high initial anatomic success rates with peak use between 2008 and 2010. Objectively they seemed to help elevate women’s pelvic organs to appropriate anatomical locations. Unfortunately there has been a high rate (10% according to a review of current literature on PubMedBarski 2015) of mesh erosion causing recurrent prolapse and/or stress urinary incontinence. Also there are cases when the mesh product perforates surrounding organs causing numerous dangerous complications. The rate of mesh-related complications according to current research is 15-25%. As a result, the FDA has reclassified the risk of synthetic mesh into a higher risk category so that the public has an increased awareness of the risk involved in these types of surgeries.

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2015, reviewed the risk factors for mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (Deng, et al). They concluded the following factors increase risk of mesh erosion: younger age, more childbirths, premenopausal states, diabetes, smoking, concomitant hysterectomy, and surgery performed by a junior surgeon. Moreover, concomitant POP surgery and preservation of the uterus may be the potential protective factors for mesh erosion.

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2015, reviewed the risk factors for mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (Deng, et al). They concluded the following factors increase risk of mesh erosion: younger age, more childbirths, premenopausal states, diabetes, smoking, concomitant hysterectomy, and surgery performed by a junior surgeon. Moreover, concomitant POP surgery and preservation of the uterus may be the potential protective factors for mesh erosion.

It is a common practice to perform a hysterectomy with a POP surgery. Reason being that the oversized uterus from childbearing adds extra weight on pelvic organs. However, the latter study as well as two other recent studies published in 2015 (Huang, Farthmann) also provide evidence that there is no benefit to a concomitant hysterectomy at the 2.5 year follow up and can lead to less satisfaction with surgery according to patient surveys respectively.

Keep in mind that all pelvic floor surgeries do not use the same amount of mesh material and different procedures have different risks associated with them. One retrospective study (Cohen, 2015) addressing incidence of mesh extrusion categorized 576 subjects into three categories: pubo-vaginal sling (PVS) (a small string of mesh around the urethra specifically addressing stress urinary incontinence only); PVS and anterior repair (also referred to as cystocele or bladder prolapse); and PVS with anterior and/or posterior repairs (also referred to as rectocele or rectal prolapse). Mesh extrusion for these types of procedures occurred at the follow rates: approximately 6% for PVS subjects, 15% for PVS + anterior repair, and 11% for PVS + anterior and/or posterior repair. This study did not account for any other types of mesh-related complications.

Pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence make up some of the most common conditions for which patients seek Pelvic Floor physical therapy and perhaps this will allow us to better speak to current research on surgical options.

1. Barski D, Deng EY. Management of Mesh Complications after stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolaps repair: review and analysis of the current literature. Biomed Research International; 2015Article ID 831285.

2. Deng T. et al. Risk factor for mesh erosion after female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU International. Doi:10.1111/bju.13158.

3. Huang LY, et al. Medium-term comparison of uterus preservation versus hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse treatment with prolift mesh. International Urogynecology Journal. 2015;26(7):1013-20.

4. Farthmann J, et al. Functional outcome after pelvic floor reconstructive surgery with or without concomitant hysterectomy. Archives of Gynec and Obstet. 2015; 291(3):573-7.

5. Cohen S, Kaveler E. The incidence of mesh extrusion after vaginal incontinence and pelvic floor prolapse surgery. J of Hospital Admin. 2014; 3(4): www.sciedu.ca/jha.

The following post comes to us from Herman & Wallace faculty member Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, BCB-PMD, PRPC. Allison authored "Use of transabdominal ultrasound imaging in retraining the pelvic-floor muscles of a woman postpartum" and is a leading expert in the use of ultrasound imaging for pelvic rehab. She is the author and instructor of the Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging: Women’s Health and Orthopedic Topics offered with Herman & Wallace.

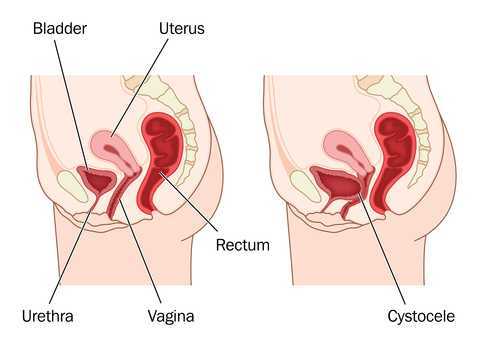

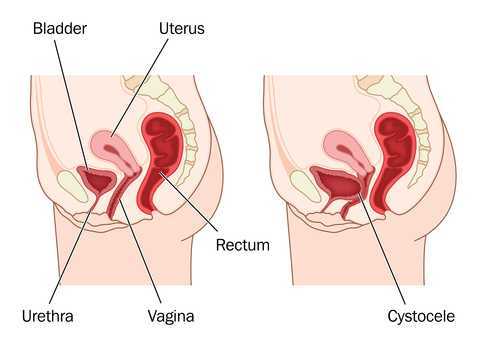

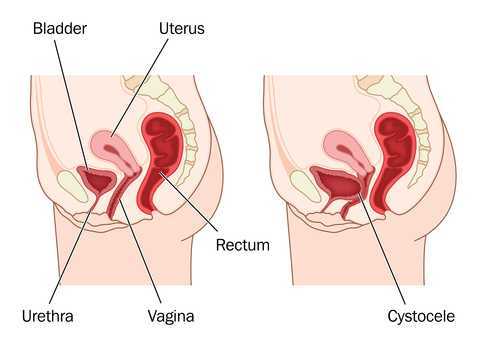

In the pelvic floor series we learn how to perform examinations for cystoceles and rectoceles. It can be more difficult for therapists to examine and quantify the degree of uterine descent. In the last few years translabial ultrasound imaging has also been used to identify what is happening in the anterior compartment upon Valsalva and pelvic floor contraction, including the uterus. This is helpful when trying to determine the degree of uterine prolapse. Degree of pelvic organ descent visible on by ultrasound has been shown to have a near-linear relationship with measures on the POPQ.

Clinically we see that some patients with severe prolapses have few symptoms, while other patients with smaller prolapses will have more severe complaints of symptoms. This can be puzzling to the clinician who is trying to treat prolapse patients. Shek and Dietz performed a study to set cutoff measures of uterine descent that will predict symptoms of prolapse. Translabial ultrasound imaging was performed on 538 women with 263 women reporting prolapse symptoms. Seventy-five percent of the women presented with grade two or greater prolapse on the POPQ, with most of being cystoceles or rectoceles. The women with more complaints of symptoms of prolapse were more likely to have uterine prolapse. There was a strong association between degree of uterine descent and symptoms of prolapse. They determined that an optimal cutoff to predict symptoms of prolapse due to uterine descent is a cervix descending to 15 mm above the pubic symphysis.

Clinically we see that some patients with severe prolapses have few symptoms, while other patients with smaller prolapses will have more severe complaints of symptoms. This can be puzzling to the clinician who is trying to treat prolapse patients. Shek and Dietz performed a study to set cutoff measures of uterine descent that will predict symptoms of prolapse. Translabial ultrasound imaging was performed on 538 women with 263 women reporting prolapse symptoms. Seventy-five percent of the women presented with grade two or greater prolapse on the POPQ, with most of being cystoceles or rectoceles. The women with more complaints of symptoms of prolapse were more likely to have uterine prolapse. There was a strong association between degree of uterine descent and symptoms of prolapse. They determined that an optimal cutoff to predict symptoms of prolapse due to uterine descent is a cervix descending to 15 mm above the pubic symphysis.

This study intrigues me and makes me wonder how much we are focusing on cystoceles and rectoceles and not looking at uterine prolapses. Using translabial ultrasound imaging is a nice tool to allow the clinician to see what is going on with all of the pelvic organs. With one Valsalva maneuver you are able to assess a lot of information including support of the pelvic organs. It also gives the clinician another way to quantify the degree of prolapse. Ultrasound imaging is a wonderful tool that clinicians can use for assessment as well as a biofeedback tool. If you are interested in learning how to perform this type of assessment, I will be teaching Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging: Women’s Health and Orthopedic Topics May 1-3 in Dayton, OH.

Shek KL, Dietz HP. What is abnormal uterine descent on translabial ultrasound? Int. Urogynecol J. 2015; 26(12)1783-7.

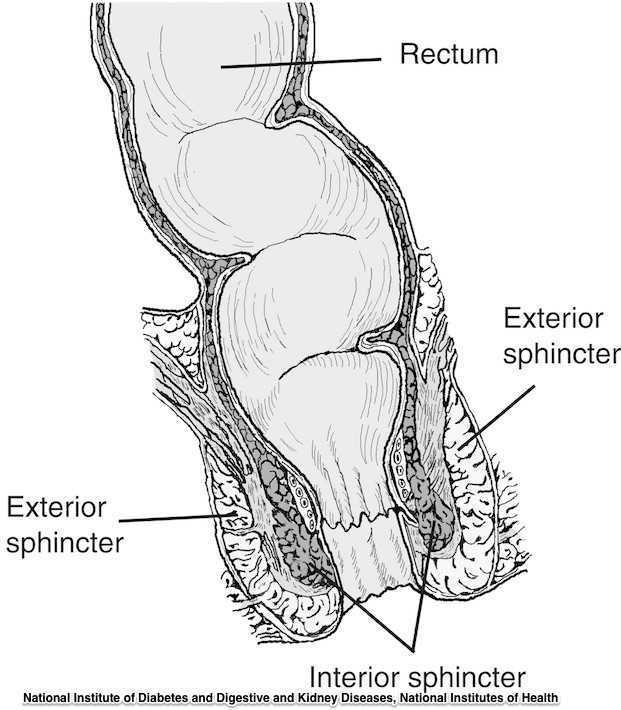

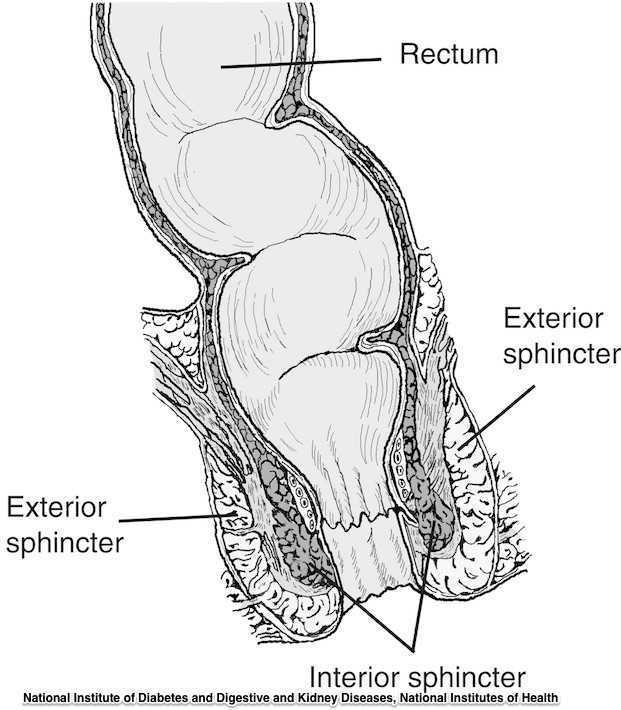

The phrase “rectal prolapse” may be easily confused with the term “rectocele” yet they may be very distinct clinical presentations. A rectocele refers to a prolapse of the posterior wall of the vagina that allows the rectum to bulge forward towards the posterior vaginal wall. This condition occurs most often in women rather than men. A rectal prolapse is a protruding of the rectum itself outside of the anal verge or opening. An overview article published in 2013 in the Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery provides information about the condition that may assist the pelvic rehabilitation provider with valuable clinical concepts. Prior to becoming a full external prolapse, an internal intussusception may occur (and observed on defecography) and progress to include an external mucosal prolapse. Rectal prolapse may occur with or without other conditions of pelvic organ descent such as a cystocele or uterine prolapse. Although the prevalence of complete rectal prolapse is low, and occurs more often in women or in elderly patients, interference with quality of life may be significant.

Symptoms can include pain, difficulty emptying the bowels, bloody and or mucous discharge, urinary incontinence, and fecal incontinence or constipation. Patients may also complain of a lump or a bulge in the rectum that may or may not improve following a bowel movement. A complete rectal prolapse can be described as a full-thickness protrusion of the rectum through the anus. A more serious consequence of this condition is strangulation of the bowel. Features of a rectal prolapse often include a redundant sigmoid colon, levator ani muscle diastasis, and loss of the vertical position of the rectum, according to the article.

Treatment of a rectal prolapse may include surgery. Prior to surgery, a physical exam, colonoscopy, anoscopy, and possibly manometry and defecography may be completed. The surgical goals are to correct the prolapse, improve any complaints of discomfort, and to resolve bowel dysfunction. Surgical approaches may include abdominal or perineal approaches, minimally invasive versus open surgery, and techniques can include posterior versus ventral and rectopexy with or without sigmoidectomy. For more details about the specific approaches for rectal prolapse repair, see the linked article. The authors of this overview article point out that because “…there is a paucity of data evaluating the effectiveness and appropriateness of the various surgical techniques…”, there is not one single management strategy for each patient.

Nonsurgical recommendations for management of a rectal prolapse include appropriate daily fluid and fiber, suppositories or enemas if needed, biofeedback training, and pelvic floor muscle exercises. A patient may benefit from education in all of these concepts, before and/or following surgery. Pelvic rehabilitation providers are well poised to offer conservative management in these conditions prior to and following any needed surgery.

To learn more about rectal prolapse and related dysfunctions, join Dr. Lila Abbate, PT, DPT, MS, OCS at Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction and the Pelvic Floor this November in New York, NY!