Instructor Sarah Hughes, PT, DPT, OCS, CF - L2 sat down with The Pelvic Rehab Report to answer a couple of questions about treating the Crossfit and weightlifting community. Dr. Hughes earned a BS in exercise science from Gonzaga University and a DPT from the University of Washington.

Sarah's specialties include dance medicine, the CrossFit and weightlifting athlete, and conditions of the hip and pelvis such as femoroacetabular impingement and labral tears. She began coaching other PTs who wanted to start their own practices in 2017 and co-founded Full Draw Consulting with her partner Dr. Kate Blankshain.

Sarah teaches Weightlifting and Functional Fitness Athletes, which s scheduled for August 7th and October 15th of this year.

What are three things you wish you knew when you first started treating the athletic community?

First, I wish that I had had the confidence to treat these athletes the way I saw fit earlier in my career. For a long time, I felt weird treating CrossFit athletes in the clinics I worked in because I felt that my peers were judging me. My colleagues (and many PTs at the time) were wary about the sport and believed it was dangerous for patients. This is a viewpoint I am working to change in our profession.

Secondly, I wish I knew more about how to scale movements in a way that is relevant to the patients and the stimulus they are striving for. For example, if a patient wants to be able to do kipping pull-ups in a workout, giving them banded strict pull-ups as a substitute is not the only option. What about the metabolic conditioning part of the equation? What about looking at the volume and how that is impacting the tissue of concern? This is a big topic that we discuss in my course.

And finally, I wish I knew that being an effective therapist for these athletes does not mean being the top athlete in the gym. In fact, just as with coaching, you do not have to be a great athlete to be a great PT. Again, this is something that I want to change as far too few physical therapists are comfortable treating these or advertising that they treat these athletes because they are not Crossfit athletes (or are not ELITE Crossfit athletes) themselves.

What lesson have you learned in a course, from an instructor, or from a colleague or mentor that has stayed with you?

One important lesson that has stayed with me came from a colleague in Seattle who started her business a year before I started mine. She told me that I needed to listen to my gut when it came to treating these athletes. She reminded me that my experience with CrossFit as a sport, as an athlete, as a coach, and as a PT put me in a position to be an expert on how to help these folks. What I did not need was to allow other physical therapists to sway my thinking and cause me to doubt myself by insisting that we should not be condoning the sport. TRUST YOUR GUT. If you think you are doing what is right for the patients, you are. You might not be right for every patient and that is OK! I am certainly not the right therapist for everyone, but I am indeed right for the community I serve.

Weightlifting and Functional Fitness Athletes - Remote Course

When it comes to Crossfit and Weightlifting, opinions are divided among Physical Therapists and other clinicians. In this half-day, remote continuing education course, instructor Sarah Haran PT, DPT, OCS, CF-L2 looks at the realities and myths related to Crossfit and high-level weight-lifting with the goal of answering “how can we meet these athletes where they are in order to keep them healthy, happy and performing in the sport they love?"

This course reviews the history and style of Crossfit exercise and Weightlifting, as well as examines the role that therapists must play for these athletes. Labs will introduce and practice the movements of Crossfit and Weightlifting, discussing the points of performance for each movement. Practitioners will learn how to speak the language of the athlete and will experience what the movement feels like so that they may help their client to break it down into its components for a sport-specific rehab progression.

The goal of this course is to provide a realistic breakdown of what these athletes are doing on a daily basis and to help remove the stigma that this type of exercise is bad for our patients. It will be important to examine the holes in training for these athletes as well as where we are lacking as therapists in our ability to help these individuals. We will also discuss mindset and cultural issues such as the use of exercise gear (i.e. straps or a weightlifting belt), body image, and the concept of "lifestyle fitness". Finally, we will discuss marketing our practices to these patients.

Course Dates: August 7th and October 15

Proper breathing is discussed and taught in many ways and forms. All of this is a step in the right direction, but what if the person physically can not lengthen tissues to expand certain key structures that are essential to the breathing mechanism? In the remote course, Breathing and the Diaphragm, Aparna Rajagopal and Leeann Taptich teach different methods to identify breathing patterns, dysfunctional breathers, and how to determine motor control issues from mobility or strength issues.

Breath is utilized widely in the exercise world. Pilates uses breath for core stability. Yoga utilizes breath to help connect the body. Strength and conditioning coaches and personal trainers emphasize breath to provide power to lift. Breathing mechanics, aka proper breathing, is also core to any type of abdominal exercise.

Respiratory muscles are directly involved in these core abdominal strengthening, stability, and stretching exercises (1). Research led by DePalo, way back in 1985, concluded that the diaphragm is actively recruited during resistance exercises such as sit-ups (2). Inefficient breathing can lead to muscular imbalances, and motor control changes that can affect motor quality. Therapists are taught at length about tissue and joint mobility versus motor control or strength issues. These same principles can be applied to assess and treat the diaphragm, breathing, and abdominals.

In regards to working with patients, Aparna shares, "Different cues work with different patients. While verbal and tactile cues to correct patterns can work with some of our patients, they do not necessarily work in all of our patients. We need different ways to correct patterns in patients that have a tissue or joint mobility issue. Such issues can cause restriction and force the patient to breathe in a specific way."

Aparna and Leeann deep dive into mobility and learn to assess and treat joint restrictions of the ribs and the thoracic spine during their remote course Breathing and the Diaphragm scheduled for October 23-24, 2021. These mobility techniques combined with specific motor control and strengthening exercises can improve myofascial restrictions that restrict breathing.

Breathing and the Diaphragm will help build a foundation to improve your patients' functional activities. No matter if it is coughing, having a bowel movement, performing wall ball in CrossFit, or hitting a tennis ball!

- Luca Cavaggioni, Lucio Ongaro, Emanuela Zannin, F. Marcello Iaia, Giampietro Alberti.Effects of different core exercises on respiratory parameters and abdominal strength. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Oct; 27(10): 3249–3253. Published online 2015 Oct 30. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.3249.

- DePalo VA, Parker AL, Al-Bilbeisi F, et al.: Respiratory muscle strength training with nonrespiratory maneuvers.J Appl Physiol 1985 2004, 96: 731–734.

Kate Bailey, PT, DPT, MS, E-RYT 500, YACEP, Y4C, CPI joins the Herman & Wallace faculty with her new course on Restorative Yoga for Physical Therapists, which is launching in remote format this June 6-7, 2020. Kate brings over 15 years of teaching movement experience to her physical therapy practice with specialities in Pilates and yoga with a focus on alignment and embodiment. Kate’s pilates background was unusual as it followed a multi-lineage price apprenticeship model that included study of complementary movement methodologies such as the Franklin Method, Feldenkrais and Gyrotonics®. Building on her Pilates teaching experience, Kate began an in depth study of yoga, training with renown teachers of the vinyasa and Iyengar traditions. She held a private practice teaching movement prior to transitioning into physical therapy and relocating to Seattle.

Yoga is a common term in our current society. We can find it in a variety of settings from dedicated studios, gyms, inside corporations, online, on Zoom, at home, and on retreat. The basic structure of a typical yoga class is a number of flowing or non flowing postures, some requiring balance, some requiring going upside down, and many requiring significant mobility to achieve a certain shape. At the end of these classes is a pose called savasana, corpse pose (or sometimes translated for comfort as final resting pose). In this pose, which is often a treat for students after working through class, students lie on the ground, eyes closed, possibly supported by props, and rest. It is perhaps the only other time in the day when that person is instructed to lie on the floor in between sleep cycles.

Yoga is a common term in our current society. We can find it in a variety of settings from dedicated studios, gyms, inside corporations, online, on Zoom, at home, and on retreat. The basic structure of a typical yoga class is a number of flowing or non flowing postures, some requiring balance, some requiring going upside down, and many requiring significant mobility to achieve a certain shape. At the end of these classes is a pose called savasana, corpse pose (or sometimes translated for comfort as final resting pose). In this pose, which is often a treat for students after working through class, students lie on the ground, eyes closed, possibly supported by props, and rest. It is perhaps the only other time in the day when that person is instructed to lie on the floor in between sleep cycles.

Savasana is one of many restorative yoga postures. In the work created and popularized by Judith Hanson Lasater, PT, PhD1, restorative yoga has taken a turn away from the active physical postures, breath manipulations and meditations that are commonplace in how we think of yoga. She has focused on rest and the need for rest in our current climate of productivity, poor self-care, and difficulty managing stress and pain.

In a dedicated restorative yoga class (not a fusion of exercise then rest, or stretch then rest… which are really lovely and have their own benefits), a student comes to class, gathers a number of props, and is instructed through 3 to 5 postures, all held for long durations to complete an hour or longer class. Consider what it would look like to do 3 things over one hour with the intent of resting. It is quite counter-culture. Students have various experiences to this type of practice, but overtime many begin to feel the need for rest (or restorative practice) in a similar way that one feels thirsty or hungry.

We know the benefits of rest: being able to access the ventral vagal aspect of the parasympathetic nervous system is what Dr. Stephen Porges2 suggests supports health, growth and restoration. There is impact on the ventral vagal complex in the brainstem that regulates the heart, the muscles of the face and head, as well as the tone of the airway. To heal, we need access this pathway. To manage stress, we need to access this pathway. To be able to choose our actions rather than be reactionary, we need to access this pathway. Restorative yoga is an accessible method that may be a new tool in a patient’s tool box to help manage their nervous systems.

1. Relax and Renew: Restful Yoga for Stressful Times by Judith Hanson Lasater PT, PhD

2. Polyvagal Theory by Stephen W Porges PhD

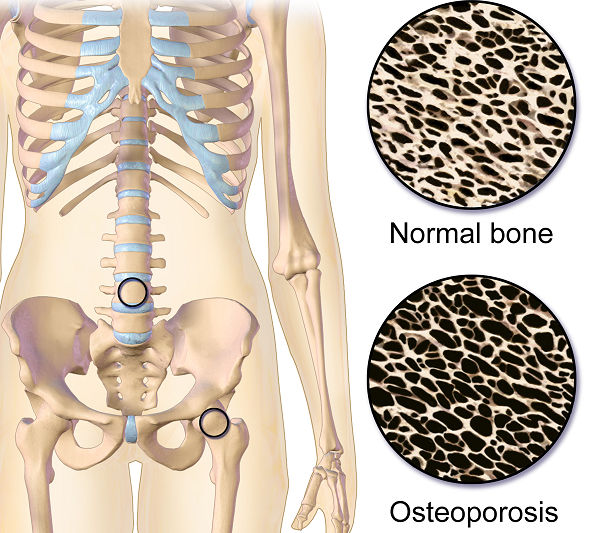

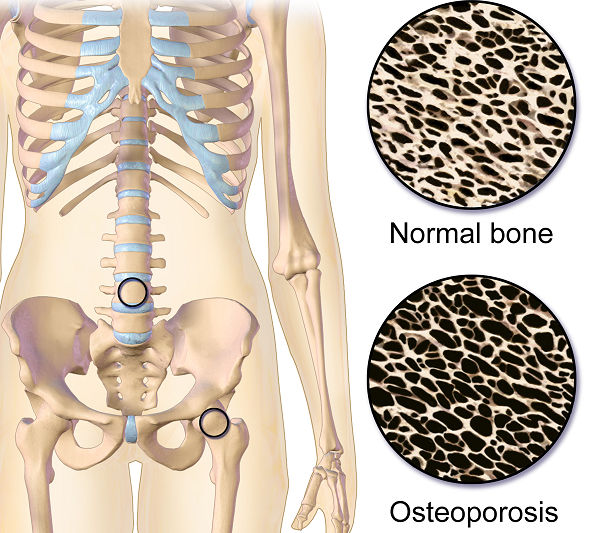

Osteoporosis or low bone mass is much more common than most people realize. Approximately 1 in 2 women over the age of 50 will suffer a fragility fracture in their lifetime. A fragility fracture is identified as a fracture due to a fall from a standing height. According to the US Census Bureau there are 72 million baby boomers (age 51-72) in 2019. Currently over 10 million Americans have osteoporosis and 44 million have low bone mass.

Many myths abound regarding osteoporosis. Answer these 5 questions below to test your Osteoporosis IQ. 1

1. “Men don’t get osteoporosis.”

Fact: In addition to the statistic above regarding the incidence of fractures in women, up to 1 in 4 men over the age of 50 will suffer a fragility fracture.

Fact: In addition to the statistic above regarding the incidence of fractures in women, up to 1 in 4 men over the age of 50 will suffer a fragility fracture.

2. “Osteoporosis is a natural part of aging.”

Fact: Although we do lose bone density as we age, osteopenia or osteoporosis is a much more significant loss than seen in normal aging. DXA (dual energy x-ray absorptiometry) is the gold standard for measuring bone density and the test shows whether an individual’s numbers fall into the normal, osteopenia, or osteoporosis range based on his or her age.

3. “I don’t need to worry about osteoporosis until I’m older.”

Fact: Osteoporosis has been called a “pediatric condition which manifests itself in old age.” Up until the age of 30 we build bone faster than it breaks down. This includes the growth phase of infants and adolescents and is also the time to build as much bone density as possible. By the age of 30, called our Peak Bone Mass, we have accumulated as much bone density as we will ever have. Proper nutrition, osteoporosis specific exercises, and good body mechanics in our formative years can all play a role in reducing the effects of low bone mass later on.

4. “I exercise regularly (including sit ups and crunches for my core). I would know if I had a fracture.”

Fact: Two myths here. Flexion based exercises such as sit-ups, crunches, and toe touches are contraindicated for osteoporosis. A landmark study done by Dr. Sinaki from Mayo clinic showed women with osteoporosis had an 89% re-fracture rate after performing flexion based exercises. 2

Fact: Secondly, only 30% of vertebral compression fractures (VCF) are symptomatic meaning many individuals fracture without knowing it. This can lead to a fracture cascade as individuals continue performing movements and exercises that are contraindicated.

5. “Tests for osteoporosis are painful and expose you to a lot of radiation.”

Fact: The DXA is a simple and painless test which lasts 5-10 minutes. You lay on your back and the machine scans over you with an open arm- no enclosed spaces. There is very little radiation. Your exposure is 10-15 times more when flying from New York to San Francisco.

How did you do? Feel free to share these myths with your patients, many of whom may have osteoporosis in addition to the primary diagnosis for which they are being treated. To learn more about treating patients with low bone density/osteoporosis, consider attending a Meeks Method for Osteoporosis course!

1. www.nof.org

2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6487063

3. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/0701/p44.html

When It Comes to Bone Building Activities for Osteoporosis, there’s Weight Bearing and then there’s Weight Bearing!

Ask just about anyone on the street what one should do for osteoporosis and the typical answer is- weight bearing exercises. And they would be partially right. Weight bearing, or loading activities have been shown to increase bone density.1 But that’s not the whole story.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

An alternative is to focus on “odd impact” loading. A study by Nikander et al 2 targeted female athletes in a variety of sports classified by the type of loading they apparently produce at the hip region; that is, high-impact loading (volleyball, hurdling), odd-impact loading (squash-playing, soccer, speed-skating, step aerobics), high magnitude loading (weightlifting), low-impact loading (orienteering, cross-country skiing), and non-impact loading (swimming, cycling). The results showed high-impact and odd-impact loading sports were associated with the highest bone mineral density.

Morques et al, in Exercise Effects on Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, found that odd impact has potential for preserving bone mass density as does high impact in older women. Activities such as side stepping, figure eights, backward walking, and walking in square patterns help “surprise the bones” due to different angles of muscular pull on the hip. The benefit, according to Nikander, is that we can get the same osteogenic benefits with less force; moderate versus high impact. This type of bone training would offer a feasible basis for targeted exercise-based prevention of hip fragility. I tell my osteoporosis patients that if they walk or run the same route, the same distance, and the same speed that they are not maximizing the osteogenic benefits of weight bearing. Providing variety to the bones creates increased bone mass in the femoral neck and lumbar spine.4

Dancing is another great activity which combines forward, side, backward, and diagonal motions to movement. In addition, it adds music to make the “weight bearing exercises” more fun. Due to balance and fall risk many senior exercise classes offer Chair exercise to music. Unfortunately sitting is the most compressive position for the spine and is particularly problematic with osteoporosis patients. Also the hips do not get any weight bearing benefit. Whenever safely possible, have patients stand; you can position two kitchen chairs on either side, much like parallel bars, to hold on to while they “dance.”

Providing creativity in weight bearing activities using odd impact allows not only for fun and stimulation; it also offers more “bang for the buck!”

- Mosekilde L. Age-related changes in bone mass, structure, and strength--effects of loading. Z Rheumatol (2000); 59 Suppl 1:1-9.

- Nikander et al. Targeted exercises against hip fragility. Osteoporosis International (2009)

- Marques et al. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Epub 2011 Sep 16

- Weidauer L. et al. Odd-impact loading results in increased cortical area and moments of inertia in collegiate athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol (2014)

Today's guest post comes from Kelsea Cannon, PT, DPT, a pelvic health practitioner in Seattle, WA. Kelsea graduated from Des Moines University in 2010 and practices at Elizabeth Rogers Pilates and Physical Therapy.

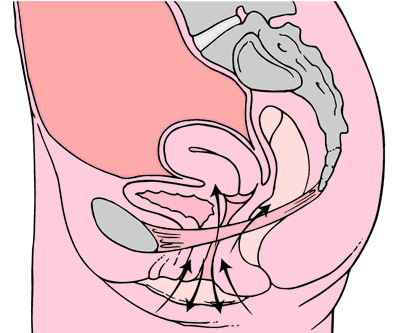

Many studies done on pelvic floor muscle training largely have subjects who are Caucasian, moderately well educated, and receive one-on-one individualized care with consistent interventions. This led a group of researchers to investigate the occurrence of pelvic floor dysfunction, specifically pelvic organ prolapse (POP), in parous Nepali women. These women are known to have high incidences of POP and associated symptomology. Another impetus to perform this research: the discovery that there was a major lack of proper pelvic floor education for postpartum women. These women were commonly encouraged to engage their pelvic floor muscles via performing supine double leg lifts, sucking in their tummies/holding their breath/counting to ten, and squeezing their glutes. These exercises would be on a list of no-no’s here in the United States. In 2017, Delena Caagbay and her team of researchers discovered that in Nepal, no one really knew the correct way to teach proper pelvic floor muscle contractions, preventing the opportunity for women to better understand their pelvic floors. The team then set out to investigate the needs of this population, with the eventual goal of providing effective pelvic floor education for Nepali women.

Caagbay and her team first wanted to know what baseline muscle activity the Nepali women had in their pelvic girdle. Physical examinations and internal pelvic floor muscle strength assessments revealed that surprisingly there was a low prevalence of pelvic floor muscle defects, such as levator avulsions and anal sphincter trauma. Uterine prolapses were most common while rectoceles were comparatively less common. Their muscles were also strong and well-functioning, often averaging a 3/5 on the Modified Oxford Scale. It was hypothesized that these women had low prevalence of muscle injury because instruments were not commonly used during childbirth, they had lower birth weight babies, and the women were typically younger when giving birth (closer to 20-21 years old). But they had a high prevalence of POP even with good muscle tone? Researchers suggested that their incidence of POP is likely stemming from their sociocultural lifestyle requirements, as women are left to do most of the daily household chores and caregiving tasks while men often travelled away from the home to perform paid labor. Physical responsibilities for these women commonly begin at younger ages and while it helps promote good muscle tone, the heavier loading places pressure on the connective tissue and fascia that support the pelvic organs. Because of the demands of their lifestyles, Nepali women are often forced to return to their physically active state within a couple weeks after giving birth.

Caagbay and her team first wanted to know what baseline muscle activity the Nepali women had in their pelvic girdle. Physical examinations and internal pelvic floor muscle strength assessments revealed that surprisingly there was a low prevalence of pelvic floor muscle defects, such as levator avulsions and anal sphincter trauma. Uterine prolapses were most common while rectoceles were comparatively less common. Their muscles were also strong and well-functioning, often averaging a 3/5 on the Modified Oxford Scale. It was hypothesized that these women had low prevalence of muscle injury because instruments were not commonly used during childbirth, they had lower birth weight babies, and the women were typically younger when giving birth (closer to 20-21 years old). But they had a high prevalence of POP even with good muscle tone? Researchers suggested that their incidence of POP is likely stemming from their sociocultural lifestyle requirements, as women are left to do most of the daily household chores and caregiving tasks while men often travelled away from the home to perform paid labor. Physical responsibilities for these women commonly begin at younger ages and while it helps promote good muscle tone, the heavier loading places pressure on the connective tissue and fascia that support the pelvic organs. Because of the demands of their lifestyles, Nepali women are often forced to return to their physically active state within a couple weeks after giving birth.

After assessing the current needs, cultural norms, and prevalence of POP in Nepali women, Caagbay et al created an illustrative pamphlet on how to contract pelvic floor muscles as well as provided verbal instruction on pelvic floor muscle activation. Transabdominal real time ultrasound was applied to assess the muscle contraction of 15 women after they received this education. Unfortunately, even after being taught how to engage their pelvic floor muscles, only 4 of 15 correctly contracted their pelvic floors.

This study highlighted that brief verbal instruction plus an illustrative pamphlet was not sufficient in teaching Nepali women how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles. Although there was a small sample size, these results can likely be extrapolated to the larger population. Further research is needed to determine how to effectively teach correct pelvic floor muscle awareness to women with low literacy and/or who reside in resource limited areas. Lastly, it is important to consider the significance of fascial and connective tissue integrity within the pelvic floor when addressing pelvic organ prolapse.

1 Can a leaflet with brief verbal instruction teach Napali women how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles? DM Caagbay, K Black, G Dangal, C Rayes-Greenow. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 15 (2), 105-109.

https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/JNHRC/article/viewFile/18160/14771

2 Pelvic Health Podcast. Lori Forner. Pelvic organ prolapse in Nepali women with Delena Caagbay. May 31, 2018.

3 The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse in a Nepali gynecology clinic. (2017) F. Turel, D. Caagbay, H.P. Dietz. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sydney Medical School Napean, University of Sydney.

4 The prevalence of major birth trauma in Nepali women. (2017) F. Turel, D. Caagbay, H.P. Dietz. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sydney Medical School Nepean, University of Sydney.

In 1984, Mersheed Sinaki MD and Beth Mikkelsen, MD published a landmark article based on their research with osteoporotic women. (Yes, it was 1984 but this is one study no one would want to reproduce).1

The study follows 59 women with a diagnosis of postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis and back pain who were divided into 4 groups that included spinal Extension (E), Flexion (F), Combined (E+F), or No Therapeutic Exercises (N). Ages ranged from 49 to 60 years (mean, 56 years). Follow-up ranged from one to six years (mean for the groups, 1.4 to 2 years). All patients had follow-up spine x-rays before treatment and at follow-up, at which time any further wedging and compression fractures were recorded. Additional fractures occurred as follows:

The study follows 59 women with a diagnosis of postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis and back pain who were divided into 4 groups that included spinal Extension (E), Flexion (F), Combined (E+F), or No Therapeutic Exercises (N). Ages ranged from 49 to 60 years (mean, 56 years). Follow-up ranged from one to six years (mean for the groups, 1.4 to 2 years). All patients had follow-up spine x-rays before treatment and at follow-up, at which time any further wedging and compression fractures were recorded. Additional fractures occurred as follows:

Group E: 16%

Group F: 89%

Group E+F: 53%

Group N: 67%

This study suggests that a significantly higher number of vertebral compression fractures occur in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis who followed a flexion based exercise program, than those using extension exercises. It also indicated that patients who did no exercises were less likely to sustain a vertebral compression fracture than those doing flexion exercises.

Due to the anatomical nature of the thoracic spine, the vertebral bodies are placed into a normal kyphosis. The anterior portion of the thoracic spine carries an excess load which can predispose an individual to fracture. Combine the propensity of flexion based daily activities such as brushing teeth, driving, texting or typing, with the fact that vertebral bodies are primarily made up of trabecular (spongy) bone and you have a recipe for disaster.

In the US, studies suggest that approximately one in two women and one in four men age 50 and older will break a bone due to osteoporosis.2 Now picture the many individuals who think that the only way to strengthen their core is by doing sit ups or crunches, further compressing the anterior portion of the spine. Often these exercises are being taught or led by fitness instructors who unknowingly put their clients at risk. Only 20-30% of compression fractures are symptomatic.3 This means that individuals may continue performing crunches, sit-ups, or toe touches even after they have fractured. No one realizes it until the person may notice a loss in height (they have trouble reaching a formerly accessible shelf or trouble hanging up clothes,) or the fracture is seen on an x-ray for pneumonia, etc. The Dowager’s Hump (hyper-kyphosis) may begin to appear. Or the person sustains another fragility fracture; possibly a hip.

Note that the E Group (Extension) still sustained fractures but significantly less than the other three groups. This suggests that there is a protective effect in strengthening the back extensors which has led to an emphasis on Site Specific back strengthening exercises as well as correct weight bearing activities.

Telling osteoporosis patients that they should exercise without giving them specific guidelines (such as in the Meeks Method) is doing them a disservice. General exercise provides minimal to no benefit in building stronger bones and the wrong exercises could put them at great risk for fractures. Educating our referral sources for the need to recommend therapists trained in correct osteoporosis management and the difference between “right” and “wrong” exercises may be the first step in reducing fragility fractures.

1. Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1984 Oct; 65.

2. NOF.org. National Osteoporosis Foundation

3. McCarthy J, MD, Davis A, MD, Am Family Physician. Diagnosis and Management of Vertebral Compression Fractures

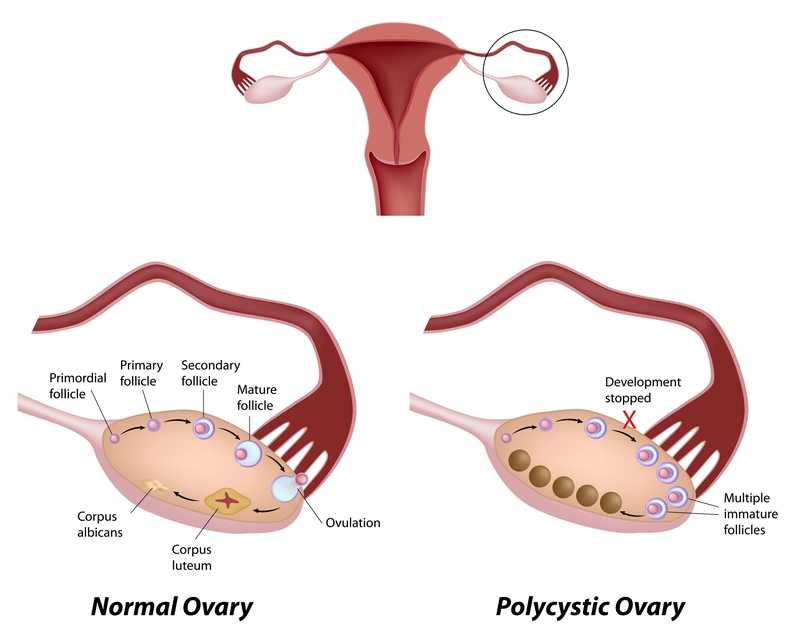

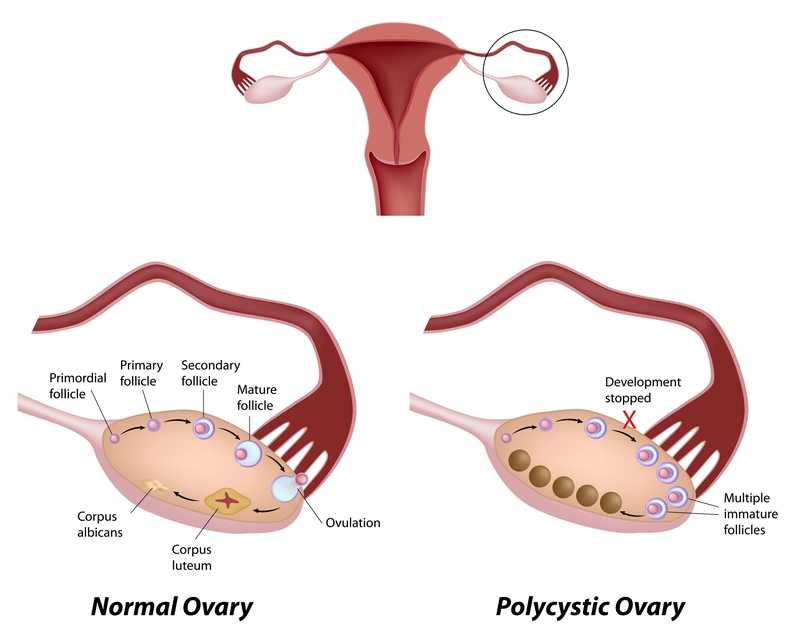

Few patients discuss polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in orthopedic manual therapy, but one lady left a lasting impression. She was adopted and did not know her family’s medical history or her genetics. At 18, she had a baby as a result of rape. At 34, she was married and diagnosed with POCS. She struggled with infertility, anxiety, obesity, and hypertension. Although I saw her for cervicalgia, the exercise aspect of her therapy had potential to impact her overall well-being and possibly improve her PCOS symptoms.

Pericleous & Stephanides (2018) reviewed 10 studies that considered the effects of resistance training on PCOS symptoms. Some of these symptoms include the absence of or a significant decrease in ovulation and menstruation, which can lead to infertility; obesity, which in turn can affect cardiovascular health and increase the risk of diabetes, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome; and, mental health problems. Research has shown resistance training benefits include lowering body fat, improving insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, and increasing insulin sensitivity in type II diabetes. Although it has been documented that obesity and insulin resistance can exacerbate PCOS symptoms, resistance training is not a common recommendation in healthcare settings for patients with PCOS . Studies have shown diet and exercise are essential to improve cardiac and respiratory health and body makeup in patients with PCOS, as the combination improves the Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), ovulation, testosterone levels, and weight loss. One systematic review found that weight loss can improve PCOS symptoms without consideration of diet; however, most other studies find intake of various macronutrients (protein, fat, carbohydrates) may lead to different results, and the effects of resistance training can only be optimized with appropriate dietary changes. These authors concluded caloric consumption and macronutrient habits must be considered in conjunction with resistance training to determine the greatest impact on improving PCOS symptoms.

Pericleous & Stephanides (2018) reviewed 10 studies that considered the effects of resistance training on PCOS symptoms. Some of these symptoms include the absence of or a significant decrease in ovulation and menstruation, which can lead to infertility; obesity, which in turn can affect cardiovascular health and increase the risk of diabetes, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome; and, mental health problems. Research has shown resistance training benefits include lowering body fat, improving insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, and increasing insulin sensitivity in type II diabetes. Although it has been documented that obesity and insulin resistance can exacerbate PCOS symptoms, resistance training is not a common recommendation in healthcare settings for patients with PCOS . Studies have shown diet and exercise are essential to improve cardiac and respiratory health and body makeup in patients with PCOS, as the combination improves the Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), ovulation, testosterone levels, and weight loss. One systematic review found that weight loss can improve PCOS symptoms without consideration of diet; however, most other studies find intake of various macronutrients (protein, fat, carbohydrates) may lead to different results, and the effects of resistance training can only be optimized with appropriate dietary changes. These authors concluded caloric consumption and macronutrient habits must be considered in conjunction with resistance training to determine the greatest impact on improving PCOS symptoms.

Benham et al., (2018) also performed a recent systematic review to assess the role exercise can have on PCOS. Fourteen trials involving 617 females of reproductive age with PCOS evaluated the effect of exercise training on reproductive outcomes. The data published did not allow the authors to quantitatively assess the impact of exercise of reproductive in PCOS patients; however, their semi-quantitative analysis allowed them to propose exercise may improve regularity of menstruation, the rate of ovulation, and pregnancy rates in these women. Via meta-analysis, secondary outcomes of body measurement and metabolic parameters significantly improved after women with PCOS underwent exercise training; however, symptoms such as acne and hirsutism (excessive, abnormal body hair growth) were not changed with exercise. The authors concluded exercise does improve the metabolic health (ie, insulin resistance) in women with PCOS, but evidence is insufficient to measure the exact impact on the function of the reproductive system.

Increasing our knowledge about comorbidities such as PCOS, regardless of our practice setting, can help us provide better education to the patients we treat. Perhaps exercise compliance can increase when patients are told multiple long-term benefits, not just immediate symptom relief. More often than not, a patient’s 4-6 week interaction with us could motivate and promote healthy lifestyle changes.

Pericleous, P., & Stephanides, S. (2018). Can resistance training improve the symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome? BMJ Open Sport — Exercise Medicine, 4(1), e000372. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000372

Benham, J. L., Yamamoto, J. M., Friedenreich, C. M., Rabi, D. M. and Sigal, R. J. (2018), Role of exercise training in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Obes, 8: 275-284. doi:10.1111/cob.12258

Suggested newly published resource for readers…

Teede, H. J., Misso, M. L., Costello, M. F., Dokras, A., Laven, J., Moran, L., … Yildiz, B. O. (2018). Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 33(9), 1602–1618. http://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey256

The new year is here and with it, lots of motivational posting about exercise and weight loss…but how is this desire for ‘new year, new you’ affecting peri-menopausal women with urinary dysfunction? It has been established that the lower urinary tract is sensitive to the effects of estrogen, sharing a common embryological origin with the female genital tract, the urogenital sinus. Urge urinary incontinence is more prevalent after the menopause, and the peak prevalence of stress incontinence occurs around the time of the menopause (Quinn et al 2009). Zhu et al looked at the risk factors for urinary incontinence in women and found that some of the main contributors include peri/post-menopausal status, constipation and central obesity (women's waist circumference, >/=80 cm) along with vaginal delivery/multiparity.

Could weight loss directly impact urinary incontinence in menopausal women? In a word – yes. ‘Weight reduction is an effective treatment for overweight and obese women with UI. Weight loss of 5% to 10% has an efficacy similar to that of other nonsurgical treatments and should be considered a first line therapy for incontinence’ (Subak et al 2005) But do these benefits last? Again – yes! ‘Weight loss intervention reduced the frequency of stress incontinence episodes through 12 months and improved patient satisfaction with changes in incontinence through 18 months. Improving weight loss maintenance may provide longer term benefits for urinary incontinence.’ (Wing et al 2010)

Could weight loss directly impact urinary incontinence in menopausal women? In a word – yes. ‘Weight reduction is an effective treatment for overweight and obese women with UI. Weight loss of 5% to 10% has an efficacy similar to that of other nonsurgical treatments and should be considered a first line therapy for incontinence’ (Subak et al 2005) But do these benefits last? Again – yes! ‘Weight loss intervention reduced the frequency of stress incontinence episodes through 12 months and improved patient satisfaction with changes in incontinence through 18 months. Improving weight loss maintenance may provide longer term benefits for urinary incontinence.’ (Wing et al 2010)

The other major health issues facing women at midlife include an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, Type 2 Diabetes and Bone Health problems – all of which are responsive to lifestyle interventions, particularly exercise and stress management. In their paper looking at lifestyle weight loss interventions, Franz et al found that ‘…a weight loss of >5% appears necessary for beneficial effects on HbA1c, lipids, and blood pressure. Achieving this level of weight loss requires intense interventions, including energy restriction, regular physical activity, and frequent contact with health professionals’. 5% weight loss is the same amount of weight loss necessary to provide significant benefits for urinary incontinence at midlife.

Successful weight management depends on nutritional intake, exercise and psychosocial considerations such as stress management, but for the menopausal woman, hormonal balance can also have an effect on not only bladder and bowel dysfunction but changing metabolic rates, thyroid issues and altered weight distribution patterns. As pelvic rehab therapists, we are all aware that pelvic health issues can be a barrier to exercise participation but sensitive awareness of the other particular challenges facing midlife women can make the difference in developing a beneficial therapeutic alliance and a journey back to optimal health. If you would like to explore the topics surrounding optimal health at menopause, why not join me in California in February?

Climacteric. 2009 Apr;12(2):106-13. ‘The effects of hormones on urinary incontinence in postmenopausal women.’ Quinn SD, Domoney C. Menopause. 2009 Jul-Aug;16(4):831-6. The epidemiological study of women with urinary incontinence and risk factors for stress urinary incontinence in China’ Zhu L, Lang J, Liu C, Han S, Huang J, Li X. J Urol. 2005 Jul;174(1):190-5. Weight loss: a novel and effective treatment for urinary incontinence’ Subak LL, Whitcomb E, Shen H, Saxton J, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS. J Urol. 2010 Sep;184(3):1005-10. Effect of weight loss on urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women: results at 12 and 18 months Wing RR, West DS, Grady D, Creasman JM, Richter HE, Myers D, Burgio KL, Franklin F, Gorin AA, Vittinghoff E, Macer J, Kusek JW, Subak LL; Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise Group. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015 Sep;115(9):1447-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.02.031. Epub 2015 Apr 29. Lifestyle weight-loss intervention outcomes in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Franz MJ, Boucher JL, Rutten-Ramos S, VanWormer JJ. Lean, M, & Lara, J & O Hill, J (2007) Strategies for preventing obesity. In: Sattar, N & Lean, M (eds.) ABC of Obesity. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing.