Osteoporosis or low bone mass is much more common than most people realize. Approximately 1 in 2 women over the age of 50 will suffer a fragility fracture in their lifetime. A fragility fracture is identified as a fracture due to a fall from a standing height. According to the US Census Bureau there are 72 million baby boomers (age 51-72) in 2019. Currently over 10 million Americans have osteoporosis and 44 million have low bone mass.

Many myths abound regarding osteoporosis. Answer these 5 questions below to test your Osteoporosis IQ. 1

1. “Men don’t get osteoporosis.”

Fact: In addition to the statistic above regarding the incidence of fractures in women, up to 1 in 4 men over the age of 50 will suffer a fragility fracture.

Fact: In addition to the statistic above regarding the incidence of fractures in women, up to 1 in 4 men over the age of 50 will suffer a fragility fracture.

2. “Osteoporosis is a natural part of aging.”

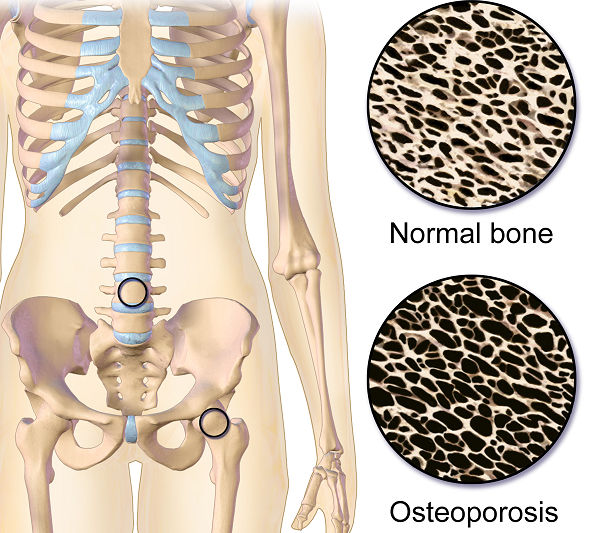

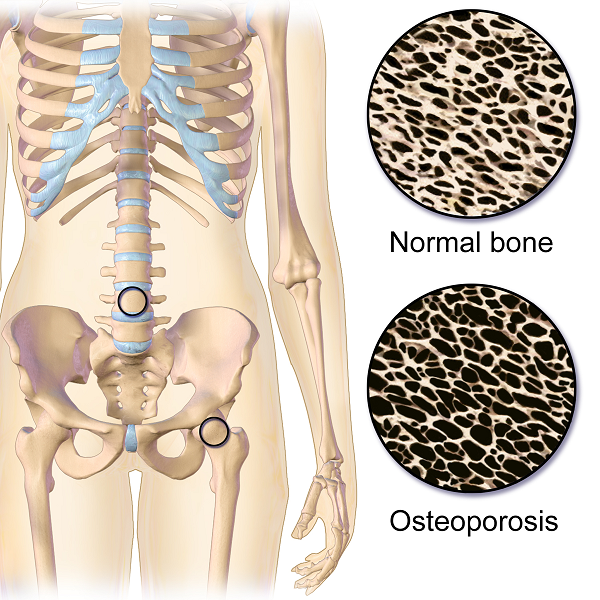

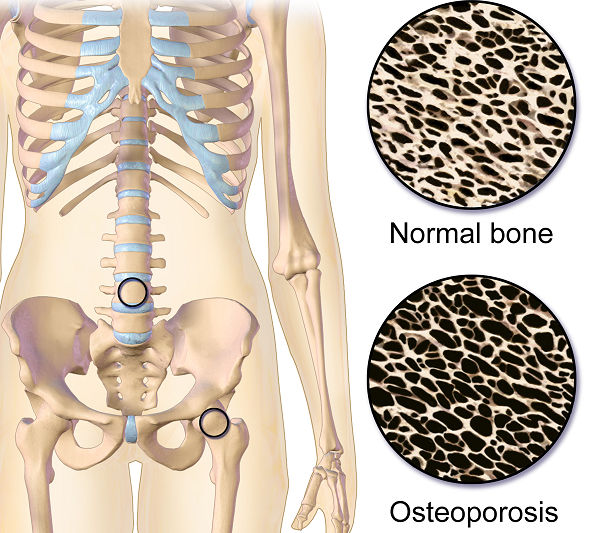

Fact: Although we do lose bone density as we age, osteopenia or osteoporosis is a much more significant loss than seen in normal aging. DXA (dual energy x-ray absorptiometry) is the gold standard for measuring bone density and the test shows whether an individual’s numbers fall into the normal, osteopenia, or osteoporosis range based on his or her age.

3. “I don’t need to worry about osteoporosis until I’m older.”

Fact: Osteoporosis has been called a “pediatric condition which manifests itself in old age.” Up until the age of 30 we build bone faster than it breaks down. This includes the growth phase of infants and adolescents and is also the time to build as much bone density as possible. By the age of 30, called our Peak Bone Mass, we have accumulated as much bone density as we will ever have. Proper nutrition, osteoporosis specific exercises, and good body mechanics in our formative years can all play a role in reducing the effects of low bone mass later on.

4. “I exercise regularly (including sit ups and crunches for my core). I would know if I had a fracture.”

Fact: Two myths here. Flexion based exercises such as sit-ups, crunches, and toe touches are contraindicated for osteoporosis. A landmark study done by Dr. Sinaki from Mayo clinic showed women with osteoporosis had an 89% re-fracture rate after performing flexion based exercises. 2

Fact: Secondly, only 30% of vertebral compression fractures (VCF) are symptomatic meaning many individuals fracture without knowing it. This can lead to a fracture cascade as individuals continue performing movements and exercises that are contraindicated.

5. “Tests for osteoporosis are painful and expose you to a lot of radiation.”

Fact: The DXA is a simple and painless test which lasts 5-10 minutes. You lay on your back and the machine scans over you with an open arm- no enclosed spaces. There is very little radiation. Your exposure is 10-15 times more when flying from New York to San Francisco.

How did you do? Feel free to share these myths with your patients, many of whom may have osteoporosis in addition to the primary diagnosis for which they are being treated. To learn more about treating patients with low bone density/osteoporosis, consider attending a Meeks Method for Osteoporosis course!

1. www.nof.org

2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6487063

3. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/0701/p44.html

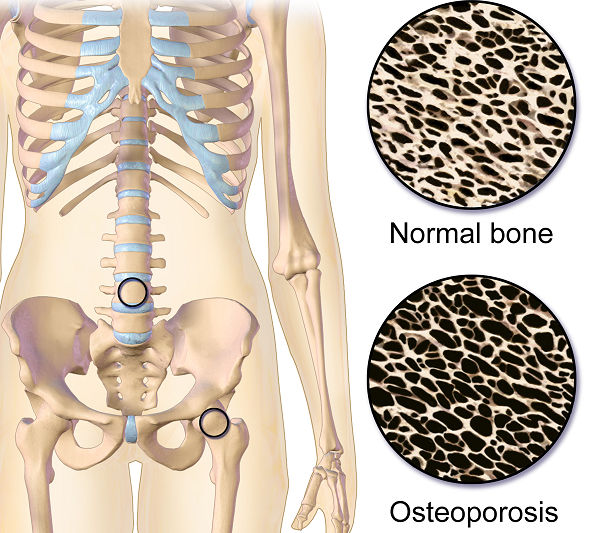

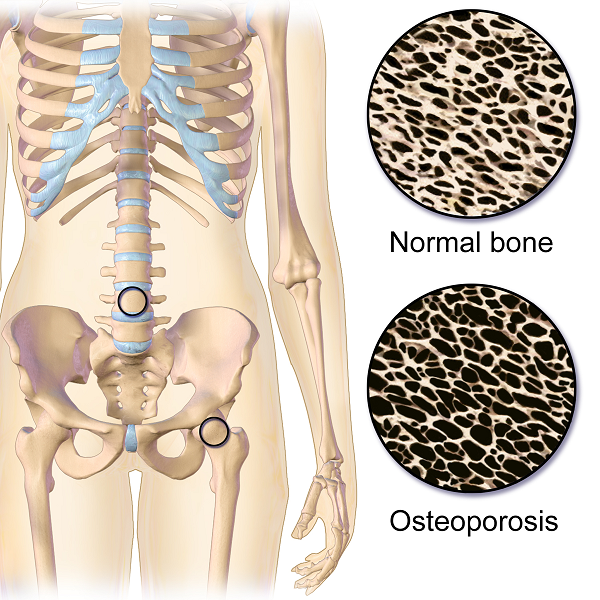

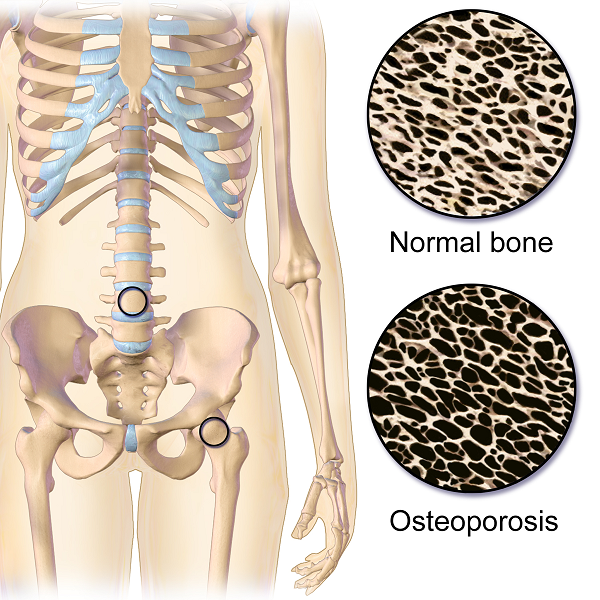

Do you work with osteoporosis patients? This may be a trick question because you probably do whether you know it or not- even if you are a pediatric therapist! Osteoporosis is defined by the World Health Organization1 as a systematic skeletal disease characterized by:

- Low bone mass

- Micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue

- Consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to a fracture

Osteoporosis occurs in men, women and even children. It is sometimes called the “silent disease” because often people don’t know they have it until they break a bone. And even then, compression fractures are painful only 20-30% of the time. Old fractures are often found on x-rays when a person is imaged for illnesses such as pneumonia. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation2, about one in two women and one in four men over the age of 50 will suffer a fracture due to bone fragility. At this point in time, it is estimated 80% of patients entering Emergency Departments with a fragility fracture (a fall from a standing height) are never followed up for care.

Osteoporosis occurs in men, women and even children. It is sometimes called the “silent disease” because often people don’t know they have it until they break a bone. And even then, compression fractures are painful only 20-30% of the time. Old fractures are often found on x-rays when a person is imaged for illnesses such as pneumonia. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation2, about one in two women and one in four men over the age of 50 will suffer a fracture due to bone fragility. At this point in time, it is estimated 80% of patients entering Emergency Departments with a fragility fracture (a fall from a standing height) are never followed up for care.

As therapists, we see patients for a variety of diagnoses with co-morbidities but osteoporosis may not be listed. This could be because they have never been identified. We are in a prime position to screen for signs associated with the disorder. Below are the top 3 signs to look for:

- History of fracture from minimal trauma (fall from a standing height, sneeze, lifting groceries, etc.) The typical fracture areas are wrist, hip, and spine although fragility fractures can happen anywhere in the body.

- Hyper-kyphosis. Note, I said hyper-kyphosis, not kyphosis. We are meant to have a thoracic kyphosis but an excessive curve, particularly when it hinges around T8 area may indicate a collapse of the anterior portion of the vertebral bodies. This is the pie shaped wedging seen on x-rays and further increases the stress on the anterior aspect of the spine. Observe your patients’ sagittal posture for proper alignment.

- Loss of height. Ask your patient their tallest height remembered; then measure them. A loss of 4 cm (1.5 inches) or more may indicate fractures in the spine.

Remember pain may or may not accompany a compression fracture. Patients may complain of a “catch” or muscle spasm or nothing at all. These quick and simple screens can alert the healthcare provider and may help prevent further disintegration of the bones. Research is showing that not only weight bearing exercises but a site specific back and hip strengthening program decreases the risk of fracture.3

1. World Health Organization. www.who.int

2. National Osteoporosis Foundation. www.nof.org

3. Current Osteoporosis Reports. Sept, 2010. The Role of Exercise in the Treatment of Osteoporosis. Sinaki M, Pfeifer M, Preisinger E, Itoi E, Rissoli R, Boonen S, Geusens P, Minne HW.

When It Comes to Bone Building Activities for Osteoporosis, there’s Weight Bearing and then there’s Weight Bearing!

Ask just about anyone on the street what one should do for osteoporosis and the typical answer is- weight bearing exercises. And they would be partially right. Weight bearing, or loading activities have been shown to increase bone density.1 But that’s not the whole story.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

An alternative is to focus on “odd impact” loading. A study by Nikander et al 2 targeted female athletes in a variety of sports classified by the type of loading they apparently produce at the hip region; that is, high-impact loading (volleyball, hurdling), odd-impact loading (squash-playing, soccer, speed-skating, step aerobics), high magnitude loading (weightlifting), low-impact loading (orienteering, cross-country skiing), and non-impact loading (swimming, cycling). The results showed high-impact and odd-impact loading sports were associated with the highest bone mineral density.

Morques et al, in Exercise Effects on Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, found that odd impact has potential for preserving bone mass density as does high impact in older women. Activities such as side stepping, figure eights, backward walking, and walking in square patterns help “surprise the bones” due to different angles of muscular pull on the hip. The benefit, according to Nikander, is that we can get the same osteogenic benefits with less force; moderate versus high impact. This type of bone training would offer a feasible basis for targeted exercise-based prevention of hip fragility. I tell my osteoporosis patients that if they walk or run the same route, the same distance, and the same speed that they are not maximizing the osteogenic benefits of weight bearing. Providing variety to the bones creates increased bone mass in the femoral neck and lumbar spine.4

Dancing is another great activity which combines forward, side, backward, and diagonal motions to movement. In addition, it adds music to make the “weight bearing exercises” more fun. Due to balance and fall risk many senior exercise classes offer Chair exercise to music. Unfortunately sitting is the most compressive position for the spine and is particularly problematic with osteoporosis patients. Also the hips do not get any weight bearing benefit. Whenever safely possible, have patients stand; you can position two kitchen chairs on either side, much like parallel bars, to hold on to while they “dance.”

Providing creativity in weight bearing activities using odd impact allows not only for fun and stimulation; it also offers more “bang for the buck!”

- Mosekilde L. Age-related changes in bone mass, structure, and strength--effects of loading. Z Rheumatol (2000); 59 Suppl 1:1-9.

- Nikander et al. Targeted exercises against hip fragility. Osteoporosis International (2009)

- Marques et al. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Epub 2011 Sep 16

- Weidauer L. et al. Odd-impact loading results in increased cortical area and moments of inertia in collegiate athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol (2014)

In 1984, Mersheed Sinaki MD and Beth Mikkelsen, MD published a landmark article based on their research with osteoporotic women. (Yes, it was 1984 but this is one study no one would want to reproduce).1

The study follows 59 women with a diagnosis of postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis and back pain who were divided into 4 groups that included spinal Extension (E), Flexion (F), Combined (E+F), or No Therapeutic Exercises (N). Ages ranged from 49 to 60 years (mean, 56 years). Follow-up ranged from one to six years (mean for the groups, 1.4 to 2 years). All patients had follow-up spine x-rays before treatment and at follow-up, at which time any further wedging and compression fractures were recorded. Additional fractures occurred as follows:

The study follows 59 women with a diagnosis of postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis and back pain who were divided into 4 groups that included spinal Extension (E), Flexion (F), Combined (E+F), or No Therapeutic Exercises (N). Ages ranged from 49 to 60 years (mean, 56 years). Follow-up ranged from one to six years (mean for the groups, 1.4 to 2 years). All patients had follow-up spine x-rays before treatment and at follow-up, at which time any further wedging and compression fractures were recorded. Additional fractures occurred as follows:

Group E: 16%

Group F: 89%

Group E+F: 53%

Group N: 67%

This study suggests that a significantly higher number of vertebral compression fractures occur in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis who followed a flexion based exercise program, than those using extension exercises. It also indicated that patients who did no exercises were less likely to sustain a vertebral compression fracture than those doing flexion exercises.

Due to the anatomical nature of the thoracic spine, the vertebral bodies are placed into a normal kyphosis. The anterior portion of the thoracic spine carries an excess load which can predispose an individual to fracture. Combine the propensity of flexion based daily activities such as brushing teeth, driving, texting or typing, with the fact that vertebral bodies are primarily made up of trabecular (spongy) bone and you have a recipe for disaster.

In the US, studies suggest that approximately one in two women and one in four men age 50 and older will break a bone due to osteoporosis.2 Now picture the many individuals who think that the only way to strengthen their core is by doing sit ups or crunches, further compressing the anterior portion of the spine. Often these exercises are being taught or led by fitness instructors who unknowingly put their clients at risk. Only 20-30% of compression fractures are symptomatic.3 This means that individuals may continue performing crunches, sit-ups, or toe touches even after they have fractured. No one realizes it until the person may notice a loss in height (they have trouble reaching a formerly accessible shelf or trouble hanging up clothes,) or the fracture is seen on an x-ray for pneumonia, etc. The Dowager’s Hump (hyper-kyphosis) may begin to appear. Or the person sustains another fragility fracture; possibly a hip.

Note that the E Group (Extension) still sustained fractures but significantly less than the other three groups. This suggests that there is a protective effect in strengthening the back extensors which has led to an emphasis on Site Specific back strengthening exercises as well as correct weight bearing activities.

Telling osteoporosis patients that they should exercise without giving them specific guidelines (such as in the Meeks Method) is doing them a disservice. General exercise provides minimal to no benefit in building stronger bones and the wrong exercises could put them at great risk for fractures. Educating our referral sources for the need to recommend therapists trained in correct osteoporosis management and the difference between “right” and “wrong” exercises may be the first step in reducing fragility fractures.

1. Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1984 Oct; 65.

2. NOF.org. National Osteoporosis Foundation

3. McCarthy J, MD, Davis A, MD, Am Family Physician. Diagnosis and Management of Vertebral Compression Fractures

The following is part three in a series documenting Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT's journey treating a 72 year old patient who has been living with multiple sclerosis (MS) since age 18. Catch up with Part One and Part Two of the patient case study on the Pelvic Rehab Report. Dr. Gulbrandson is a certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist and instructor of the Meeks Method, and she helps teach The Meeks Method for Osteoporosis course.

On Maryanne’s third visit, after reviewing her home exercises I told her that today our focus was on alignment. “In dealing with osteoporosis we want the forces that act upon our bodies to line up as optimally as possible. We have gravity providing a downward force from above and we have ground reaction forces coming up from below. Remember back to your first visit when we did the Foot Press in sitting and talked about Newton’s 3rd Law? For every action there’s an opposite and equal reaction and, how by pressing your feet down it helped you to sit straighter and gave more support to your back?” She nodded in agreement.

On Maryanne’s third visit, after reviewing her home exercises I told her that today our focus was on alignment. “In dealing with osteoporosis we want the forces that act upon our bodies to line up as optimally as possible. We have gravity providing a downward force from above and we have ground reaction forces coming up from below. Remember back to your first visit when we did the Foot Press in sitting and talked about Newton’s 3rd Law? For every action there’s an opposite and equal reaction and, how by pressing your feet down it helped you to sit straighter and gave more support to your back?” She nodded in agreement.

“Well, there’s another important component to that- one that we call optimal alignment. When we sit or stand in a flexed posture, those two opposing forces do not line up well and can put undue stress and pressure on our body, particularly the vertebral bodies.” I showed her the spine again with an increased flexion (hyper-kyphosis) in the thoracic area. “It’s normal to have a kyphosis in the thoracic spine. What we don’t want is a hyper-kyphosis. We often see the apex of the increased curve around T-7, 8, 9 levels near the bra line. We also call it the “slouch line” because from the front, that’s where we slouch in sitting. A thoracic hyper-kyphosis can lead to hyper-lordosis in the lumbar spine as the body tries to counteract the flexion forces above with extension or arching in the low back. We know that Wolff’s Law states that bone in a healthy person will adapt to the loads under which it is placed.1 But we want those loads to be optimally transmitted; otherwise the adaptation can be problematic.”

With Maryanne sitting in a Perch Posture position on the side of the low mat table, I placed a 4 foot dowel rod alongside her back, touching her sacrum and apex of her thoracic curve. I instructed her to bring her occiput back toward the dowel without extending her neck. I wanted her to do more of a cervical retraction move. She was a good 3+ inches away. Previously I had measured her using the WOD (Wall to Occiput Distance).2 This helps patients understand when they are forward flexed in the upper thoracic and cervical area and becomes an exercise as well. Since Maryanne was not safe in a standing position, we used an armless chair against the wall. I turned it sideways so the side of the chair was snugged up to the wall and transferred her to the chair, sitting so that her sacrum was flush against the wall. “Bring your upper back against the wall without allowing your low back to arch forward”, I told her as I placed a folded towel behind her head. “Now you’re going to press the back of your head into the towel, just as you do when lying down in the Re-alignment routine. Before you perform the Head Press, inhale to prepare, start your exhale, then do the head press. Hold for 3 -5 seconds as you continue to exhale, then relax as you inhale. Do 3-5 reps.”

The Head Press in standing, (or in Maryanne’s case, sitting) is a convenient way to not only strengthen the back muscles isometrically, but also increase awareness of body in space and relationship of head to trunk positioning. For any individual who has developed a forward head position over a period of years, there is a loss of the proprioceptive feedback necessary to know when we’re not in alignment, even if we have the ROM to achieve it. And often a lack of strength and especially muscle endurance to maintain that optimally aligned position is problematic. Using the wall several times a day can assist in building strength and awareness. In Maryanne’s case we needed a folded towel behind her occiput to give her something to press into and prevented her from going into increased cervical extension.

“I still want you to do the Head Press in supine as part of the Re-alignment routine everyday”, I told her. “But also practice it in sitting against a wall, making sure your sacrum is right up against it. Do this several times a day for several minutes, holding 3-5 seconds each. And be sure to use your breath to maintain neutral alignment of your lumbar spine.”

And with that, our work for the day was done.

1. Wolff's Law and bone's structural adaptations to mechanical usage: an ... https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8060014

2. Concurrent Validity of Occiput-Wall Distance to Measure Kyphosis in Communities. Journal of Clinical Trials. May 18, 2012 Sawitree Wongsa1,4, Pipatana Amatachaya2,4, Jeamjit Saengsuwan3,4 and Sugalya Amatachaya1,4*

The following is part two in a series documenting Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT's journey treating a 72 year old patient who has been living with multiple sclerosis (MS) since age 18. Catch up with Part one of the patient case study on the Pelvic Rehab Report here. Dr. Gulbrandson is a certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist and instructor of the Meeks Method, and she helps teach The Meeks Method for Osteoporosis course.

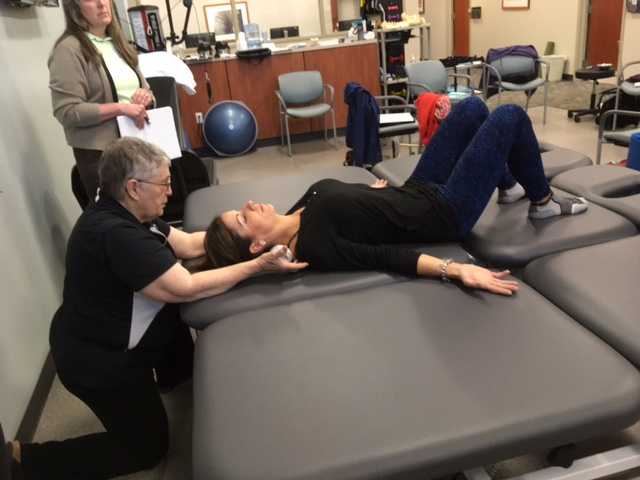

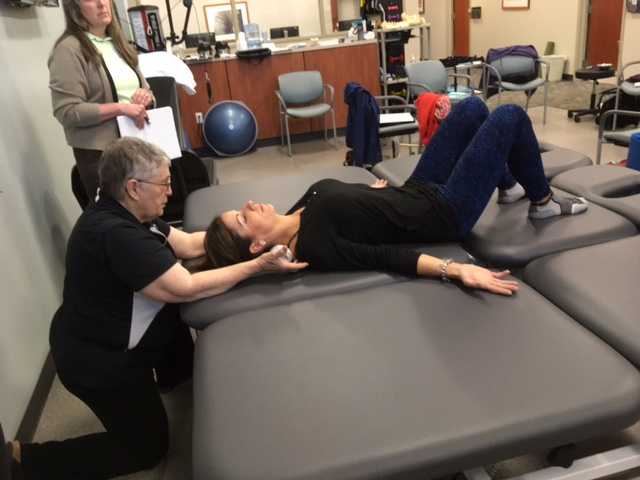

On Maryanne’s second visit, she reported she had been doing her “homework” and didn’t have any questions. Just to be sure, we reviewed them and I had her demonstrate. In Decompression position, she was lying supine with her hands on her abdomen, a common mistake I see. Usually this is due to tightness in pec minor with protracted scapulae. Patients unknowingly resort to the path of least resistance to take the strain off of the muscles. I explained to her that we want to use gravity to gently lengthen those muscles and “widen” the collarbones to allow for improved alignment. With her shoulders abducted to approximately 30 degrees and palms up, I propped a couple of small towels under her forearms which allowed her shoulders to relax into a more posterior and correct position.

“Today we begin the Re-alignment routine,” I said, “starting with the Shoulder Press.” I showed her how to gently press the back of her shoulders down into the mat without arching her lumbar spine. “As you press your shoulders down, exhale through your mouth as if you’re fogging a mirror. This will help activate your core muscles to keep your back in good alignment. Hold for 2-3 seconds, and then relax. Repeat 3 times.” Maryanne looked at me as if I’d lost my mind. “Did you say do 3 reps?” she asked. “I do 2 sets of 20 reps at the gym,” she said with obvious pride in her voice. “Yes, that’s where we start, and there are a couple of reasons. First, these are very site specific exercises which focus on the exact areas that need strengthening. Exercises done in a gym setting are often more general and usually involve compensation. We are minimizing any compensation such as allowing your low back to arch. There is probably weakness in those upper back muscles as well as the tightness seen in your anterior chest muscles and we need to go slowly. Also, we are simultaneously stretching while we strengthen. Our society is so forward biased (we work on computers, drive cars, make beds, eat- it’s all forward, forward, forward), that the anterior muscles get tight and the upper back muscles get overstretched and weak. We need to reverse that pattern. Take a look at our younger population and their texting postures. Yikes! We will be layering on more exercises as your technique improves so you’ll be doing more than just 3 reps, I promise.”

After the Shoulder Press we proceeded with the Head Press, Leg Lengthener and Arm Lengthener, spending time to make sure her cervical spine stayed in neutral as she pressed her head down into the mat. Head Press (cervical retraction) performed in supine allow patients to have something to press against and helps inhibit the tendency to move into cervical extension. It can also be done standing against the wall with a small pillow or folded towels between the occiput and the wall.

We ended with Maryanne in standing at the kitchen sink to promote functional activities and weight bearing positions. I reminded her to do the Foot Press through the floor using the Triangle of Foot Support visual. This helped to elongate her spine. “Imagine a bungie cord running from the top back of your head to the ceiling” I said which further increased her standing height. “Now I want you to imagine a shelf running straight out from your breastbone with a glass of some very expensive fine drink sitting on it. Do not spill your libation! Oh, and one last thing Maryanne. Breathe!!!” At which point she collapsed into laughter and our session was over. “Busted”, she said.

The following case study comes from faculty member Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT, a certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist and instructor of the Meeks Method. Join Dr. Gulbrandson in The Meeks Method for Osteoporosis on September 22-23, 2018 in Detroit, MI!

The first sight I had of my new patient was watching her being wheeled across the parking lot by her husband. A petite 72-year-old, I could see her slouched posture in the wheelchair. With the double diagnosis of osteoporosis and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) it didn’t look good. However, “Maryanne“ greeted me with a wide grin and a friendly, “I’m so excited to be here. I’ve heard good things about this program and can’t wait to get started.“

That’s what I find with my osteoporosis patients. They are highly motivated and willing to do the work to decrease their risk of a fracture. Maryanne was unusual in that she was diagnosed with MS at a very young age. She was 18 and had lived with the disease in a positive manner. She exercised 3X a week and had a caring, involved husband. They worked out at a local health club, taking advantage of the Silver Sneakers program. Maryanne was able to stand holding onto the kitchen counter but had stopped walking five years ago due to numerous falls. She performed standing transfers with her husband providing moderate to max assist. Her osteoporosis certainly put her at a high risk for fracture.

That’s what I find with my osteoporosis patients. They are highly motivated and willing to do the work to decrease their risk of a fracture. Maryanne was unusual in that she was diagnosed with MS at a very young age. She was 18 and had lived with the disease in a positive manner. She exercised 3X a week and had a caring, involved husband. They worked out at a local health club, taking advantage of the Silver Sneakers program. Maryanne was able to stand holding onto the kitchen counter but had stopped walking five years ago due to numerous falls. She performed standing transfers with her husband providing moderate to max assist. Her osteoporosis certainly put her at a high risk for fracture.

Even though she had been exercising on a regular basis, she was unfortunately doing many of the wrong exercises. Her workout consisted of sit-ups and crunches. She used the Pec Deck bringing her into scapular protraction and facilitating forward flexion. She was also stretching her hamstrings by long sitting reaching to touch her toes.

Spinal flexion is contraindicated in patients with osteoporosis. A landmark study done in 19841 divided a group of women with osteoporosis into 4 groups. One group performed extension based exercises, a second group did flexion. A third group used a combination of flexion and extension and the fourth was the control and did no exercises. Below are the results 1-6 years later.

- Extension Group: 16% incidence of fracture or wedging of vertebral bodies

- Flexion Group: 89% rate.

- Combination Extension/Flexion: 53% rate

- No Exercise Group: 67%

The results were astounding. Granted, it was a small study- 59 participants and it was done a long time ago. But this is a one study that no one wants to repeat, or volunteer for!

Several take home messages followed this study.

- Flexion is contra-indicated for individuals with osteoporosis.

- It’s better to do no exercise than the wrong exercise. The No Exercise group faired better than the Flexion group although at 67% it’s clear that many of our everyday activities- making beds, placing items on low shelves, and now computing and texting put us at risk.

Sadly, many individuals with osteoporosis are told by their physicians to start exercising.......but without any guidance they do what Maryanne did. Just start exercising. And putting themselves at greater risk.

Maryanne was also doing nothing to strengthen her back extensors and scapular area. After giving an overview of the vertebral bodies, pelvis, and hip joint with my trusty spine, I showed both my patient and her husband how forward flexion puts increased compression on the anterior aspect of the spine, particularly in the thoracic curve at T 7, 8, 9, the most common site of compression fractures. We started with Decompression, which is the beginning position for the Meeks method. Many therapists know this as hooklying. This position allows the spinous processes to press against the hard surface of the floor, opening up the anterior portion of the spine and providing tensile forces throughout the length of the spine. With the help of her husband, Maryanne could get down on the floor but I often advise patients who are unable to safely transfer to the floor to lay across the end of their bed. This is less cushy than lying longways where they sleep. Adding a yoga mat or a quilt on top to give more firmness improves the effect.

Supine is the least compressive of all positions; sitting is the most compressive. While Decompression may not seem like much of an exercise it is vital to reduce the effects of gravity and compression on the spine.

We addressed sitting posture by firming up the base of her wheelchair as well as recommending transferring into other chairs and positions frequently throughout the day. Spending time sitting towards the edge of a firm chair in what we call Perch Posture and practicing Foot Presses into the floor created improved alignment in her spine as well as isometrically activating glutes, abs, quads. Using the Foot Press is an example of Newtons 3rd Law, “For every action there’s an equal and opposite reaction” so by pressing her feet down she actually lengthened her torso and head. We also discussed discontinuing the contraindicated exercises in her workout routine and I assured her that the Meeks method would progressively challenge her core (the reason everyone thinks they should do sit-ups) and target the right muscles to help strengthen her bones. We use site specific exercises to target certain muscles that pull on the bone and increase bone strength.2

With instructions to Decompress several times daily to reduce compression on the spine along with the other adjustments made, I felt Maryanne was on her way to reducing her risk of fracture and increasing the quality of her life. She thanked me profusely for the education and the exercise of that session. We both look forward to the next one.

1. Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984 Oct;65(10):593-6.

2. Frost HM1. Wolff's Law and bone's structural adaptations to mechanical usage: an overview for clinicians. Angle Orthod. 1994;64(3):175-88.

The expression, “the canary in the coal mine” comes from a long ago practice of coalminers bringing canaries with them into the coalmines. These birds were more sensitive than humans to toxic gasses and so, if they became ill or died, the coalminers knew they had to get out quickly. The canaries were a kind of early warning signal before it was too late. Even though the practice has been discontinued, the metaphor lives on as a warning of serious danger to come.

Osteoporosis, which means porous bones, has been called a silent disease because often an individual doesn’t know he or she has it until they break a bone. The three common areas of fracture are the wrist, the hip, or the spine. Osteoporosis fractures are called fragility fractures, meaning they happen from a fall of standing height or less. We should not break a bone just by a fall unless there is an underlying cause which makes our bones fragile.

Wrist fractures typically happen when a person starts to fall and puts his or her arms out to catch themselves. They often are seen in the Emergency Department but seldom followed up with an Osteoporosis workup. According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation’s Capture the Fracture program, 80% of fracture patients are never offered screening and / or treatment for osteoporosis. As professionals working with patients who often have co-morbidities, we can be the ones to screen for osteoporosis and balance problems, particularly if our patients have a history of fractures. These screens include the following:

Wrist fractures typically happen when a person starts to fall and puts his or her arms out to catch themselves. They often are seen in the Emergency Department but seldom followed up with an Osteoporosis workup. According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation’s Capture the Fracture program, 80% of fracture patients are never offered screening and / or treatment for osteoporosis. As professionals working with patients who often have co-morbidities, we can be the ones to screen for osteoporosis and balance problems, particularly if our patients have a history of fractures. These screens include the following:

1. Check for the three most common signs of osteoporosis:

a. History of fractures

b. Hyper-kyphosis of the thoracic spine

c. Loss of height equal or greater than 4 cm.

2. Grip Strength

Low grip strength in women is associated with low bone density1

3. Rib-pelvic distance- less than two fingerbreadths.

With the patient standing with their back to you, arms raised to 90 degrees, check the distance from the lowest rib to the iliac crest. Two fingerbreadths or less may be indicative of a vertebral fracture.

A prior fracture is associated with an 86% increased risk of any fracture based on a 2004 meta-analysis by Kanis, Johnell, and De Laet in Bone 2. Fracture predicts fracture. It is our duty as professionals and as human beings to intervene by screening and referring out even if this is not the primary reason we are treating this patient. Fractures from osteoporosis can be devastating, resulting in increased risk of mortality at worst and a diminished quality of life at best. Look for the canaries in the coal mine. Our patients deserve to live the quality of life they envision.

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT, CEEAA teaches the Meeks Method for Osteoporosis Management seminars for Herman and Wallace around the country.

1. Dixon WG et al. Low grip strength is associated with bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in women. Rheumatology 2005;44:642-646

2. Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, et al. (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 35:375

On my son’s due date, I ran 5 miles (as I often did during my pregnancy), hoping he would be a New Year’s baby. The thought of low bone density never crossed my mind, even living in Seattle where the sun only intermittently showers people with Vitamin D. However, bone mineral density changes do occur over the course of carrying a fetus through the finish line of birth. And sometimes women experience a relatively rare condition referred to as pregnancy-related osteoporosis.

Krishnakumar, Kumar, and Kuzhimattam2016 explored vertebral compression fracture due to pregnancy-related osteoporosis (PAO). The condition was first described over 60 years ago, and risk factors include low body mass index, physical inactivity, low calcium intake, family history, and poor nutrition. Of 535 osteoporotic fractures considered, 2 were secondary to PAO. A 27-year-old woman complained of back pain during her 8th month of pregnancy, and 3 months postpartum, she was found to have a T10 compression fracture. A 31-year-old with scoliosis had back pain at 1 month postpartum but did not seek treatment until 5 months after giving birth, and she had T12, L1, and L2 compression fractures. The women were treated with the following interventions: cessation of breastfeeding, oral calcium 100 mg/day, Vitamin D 800 IU/day, alendronate 70 mg/week, and thoracolumbar orthosis. Bone density improved significantly, and no new fractures developed during the 2-year follow up period.

Nakamura et al.2015 reviewed literature on pregnancy-and-lactation-associated osteoporosis, focusing on 2 studies. The authors explained symptoms of severe low back, hip, and lower extremity joint pain that occur postpartum or in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy can be secondary to this disorder, but it is often not considered immediately. A 30-year-old woman with such debilitating pain in her spine with movement 2 months postpartum had to stop breastfeeding, and 10 months later, she was found to have 12 vertebral fractures. She had low bone mineral density (BMD) in her lumbar spine, and she was given 0.5mg/day alfacalcidol (ALF), an active vitamin D3 analog, as well as Vitamin K. No more fractures developed over the next 6 years. A 37-year-old female had severe back pain 2 months postpartum, and at 7 months was found to have 8 vertebral fractures due to PAO. Her pain subsided after stopping breastfeeding, using a lumbar brace, and supplementing with 0.5mg/day ALF and Vitamin K. The authors concluded goals for treating PAO include preventing vertebral fractures and increasing BMD and overall fracture resistance with Vitamins D and K.

Other treatment approaches for similar case presentations have been published. One gave credit to denosumab injections giving pain relief and improved BMD to 2 women, ages 35 and 33, after postpartum vertebral fractures (Sanchez, Zanchetta, & Danilowicz2016). Guardio and Fiore2016 reported success using the amino-bisphosphonates, neridronate, in a 38-year-old with PAO T4 fracture.

Thankfully for these women experiencing PAO vertebral fractures, supplements boosted their BMD and prevented further fractures. However, they all had to prematurely stop breastfeeding to reduce their pain as well. This rare condition can be used as a warning for women to proactively increase their BMD. The course, Meeks Method for Osteoporosis, can help therapists implement safe, effective, and active ways to promote bone health for all - especially the pregnant population in serious need of support.

Krishnakumar, R., Kumar, A. T., & Kuzhimattam, M. J. (2016). Spinal compression fractures due to pregnancy-associated osteoporosis. Journal of Craniovertebral Junction & Spine, 7(4), 224–227. http://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8237.193263

Nakamura, Y., Kamimura, M., Ikegami, S., Mukaiyama, K., Komatsu, M., Uchiyama, S., & Kato, H. (2015). A case series of pregnancy- and lactation-associated osteoporosis and a review of the literature. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 11, 1361–1365. http://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S87274

Sánchez, A., Zanchetta, M. B., & Danilowicz, K. (2016). Two cases of pregnancy- and lactation- associated osteoporosis successfully treated with denosumab. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism, 13(3), 244–246. http://doi.org/10.11138/ccmbm/2016.13.3.244

Gaudio, A., & Fiore, C. E. (2016). Successful neridronate therapy in pregnancy-associated osteoporosis. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism, 13(3), 241–243. http://doi.org/10.11138/ccmbm/2016.13.3.241

Nancy Cullinane PT, MHS, WCS is today's guest blogger. Nancy has been practicing pelvic rehabilitation since 1994 and she is eager to share her knowledge with the medical community at large. Thank you, Nancy, for contributing this excellent article!

Clinically valid research on the efficacy and safety of therapeutic exercise and activities for individuals with osteoporosis or vertebral fractures is scarce, posing barriers for health care providers and patients seeking to utilize exercise as a means to improve function or reduce fracture risk1,2. However, what evidence does exist strongly supports the use of exercise for the treatment of low Bone Mineral Density (BMD), thoracic kyphosis, and fall risk reduction, three themes that connect repeatedly in the body of literature addressing osteoporosis intervention.

Sinaki et al3 reported that osteoporotic women who participated in a prone back extensor strength exercise routine for 2 years experienced vertebral compression fracture at a 1% rate, while a control group experienced fracture rates of 4%. Back strength was significantly higher in the exercise group and at 10 years, the exercise group had lost 16% of their baseline strength, while the control group had lost 27%. In another study, Hongo correlated decreased back muscle strength with an increased thoracic kyphosis, which is associated with more fractures and less quality of life. Greater spine strength correlated to greater BMD4. Likewise, Mika reported that kyphosis deformity was more related to muscle weakness than to reduced BMD5. While strength is clearly a priority in choosing therapeutic exercise for this population, fall and fracture prevention is a critical component of treatment for them as well. Liu-Ambrose identified quadricep muscle weakness and balance deficit statistically more likely in an osteoporotic group versus non osteoporotics6. In a different study, Liu-Ambrose demonstrated exercise-induced reductions in fall risk that were maintained in older women following three different types of exercise over a six month timeframe. Fall risk was 43% lower in a resistance-exercise training group; 40% lower in a balance training exercise group, and 37% less in a general stretching exercise group7.

Sinaki et al3 reported that osteoporotic women who participated in a prone back extensor strength exercise routine for 2 years experienced vertebral compression fracture at a 1% rate, while a control group experienced fracture rates of 4%. Back strength was significantly higher in the exercise group and at 10 years, the exercise group had lost 16% of their baseline strength, while the control group had lost 27%. In another study, Hongo correlated decreased back muscle strength with an increased thoracic kyphosis, which is associated with more fractures and less quality of life. Greater spine strength correlated to greater BMD4. Likewise, Mika reported that kyphosis deformity was more related to muscle weakness than to reduced BMD5. While strength is clearly a priority in choosing therapeutic exercise for this population, fall and fracture prevention is a critical component of treatment for them as well. Liu-Ambrose identified quadricep muscle weakness and balance deficit statistically more likely in an osteoporotic group versus non osteoporotics6. In a different study, Liu-Ambrose demonstrated exercise-induced reductions in fall risk that were maintained in older women following three different types of exercise over a six month timeframe. Fall risk was 43% lower in a resistance-exercise training group; 40% lower in a balance training exercise group, and 37% less in a general stretching exercise group7.

These studies allow us to unequivocally conclude that spinal extensor strengthening and therapeutic activities aimed at improving balance and decreasing fall risk are tantamount as therapeutic interventions for osteoporosis. But postural education/modification and weight bearing activities aimed at stimulating osteoblast production intended to improve BMD are a reasonable component of an osteoporosis treatment plan, despite the lack of concrete evidence for them. Nutrition and mineral supplementation with calcium and vitamin D have been shown to reduce morbidities, and hence we should incorporate this education into our treatment plans as well8, 9. Studies on the efficacy of vibration platforms hold promise, but thus far, have not been substantiated as an evidence-based intervention to improve BMD.

Too Fit To Fracture: outcomes of a Delphi consensus process on physical activity and exercise recommendations for adults with osteoporosis with or without vertebral fractures1,2 is a multiple-part publication in the journal Osteoporosis International, based upon an international consensus process by expert researchers and clinicians in the osteoporosis field. These publications include exercise and physical activity recommendations for individuals with osteoporosis based upon a separation of patients into to three groups: osteoporosis based on BMD without fracture; osteoporosis with one vertebral fracture; and osteoporosis with multiple spine fractures, hyperkyphosis and pain. This group of experts emphasize the importance of teaching safe performance of ADLs with respect to bodymechanics as a priority to accompany strength, balance, fall & fracture prevention, nutrition and pharmacotherapy management. They promote establishment of an individualized program for each patient with adaptable variations of these concepts, with the most accommodation allotted for individuals with multiple vertebral compression fractures. An example of such an adaptation is altering prone back extensions such as those documented in the studies by Sinaki and Hongo, into supine shoulder presses, thus strengthening the back extensors in a less gravitationally demanding posture. Osteoporosis Canada has adapted the main concepts from these publications into a patient-friendly, instructional website with reproducible handouts at http://www.osteoporosis.ca/osteoporosis-and-you/too-fit-to-fracture/

A firm conclusion from the Too Fit to Fracture project is that higher quality outcomes studies are desperately needed to assist all healthcare providers in managing osteoporosis more effectively and comprehensively, and to do so prior to the onset of debilitating fractures that tend to produce serious comorbidities.

1. Giangregorio et al. Too Fit to Fracture: exercise recommendations for individuals with osteoporosis or osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Osteoporosis International. 2014; 25(3): 821-835

2. Giangregorio et al. Too Fit to Fracture: outcomes of a Delphi consensus process on physical activity and exercise recommendations for adults with osteoporosis with or without vertebral fracture. Osteoporosis International. 2015; 26(3):891-910

3. Sinaki et al. Stronger back muscles reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures: a prospective 10 year follow-up of postmenopausal women. Bone. 2002; 30: 836-841 4. Hongo et al. Effect of low-intensity back exercise on quality of life and back extensor strength in patients with osteoporosis; a randomized controlled trial.Osteoporosis International. 2007; 10: 1389-1395

5. Mika et al. Differences in thoracic kyphosis and in back muscle strength in women with bone loss due to osteoporosis. Spine. 2005; 30(2): 241-246

6. Liu-Ambrose et al. Older women with osteoporosis have increased postural sway and weaker quadriceps strength than counterparts with normal bone mass: overlooked determinants of fracture risk? J Gerontology, Series A Biolog Sci Med Sci. 2003; 58(9): M862-866

7. Liu-Ambrose et al. The beneficial effects of group-based exercise on fall risk profile and physical activity persist 1 year post intervention in older women with low bone mass: follow-up after withdrawal of exercise. J Am Geriat Soc. 2005; 53 (10): 1767-1773

8. Ensrud et al. Weight change and fractures in older women: study of osteoporotic fractures research group. Archives Int Med. 1997; 157 (8): 857-863

9. Kemmler et al. Exercise effects on fitness and bone mineral density in early postmenopausal women: 1-year EFOPS results. Med and Sci in Sports Ex. 2002; 34 (12): 2115-2123