Pelvic pain can often involve adverse neural tension. The hip and pelvic nerves wrap around like spaghetti, making diagnosis and treatment difficult. Is the pain driver boney, capsular, muscle or neurovascular? Luckily, impingement and labral tears are fairly easy to diagnosis. Nerve entrapment can be a little bit tricky to diagnosis and treat. Part of being a good pelvic floor physical therapist is appropriately diagnosing and then partnering with patients to treat symptoms, pain, and movement dysfunction.

The authors of this study focused on hip, so this blog focuses on sciatic and pudendal nerve entrapment in the athletic population. Nerve entrapment occurs when the normal slide and glide is limited. That can be from any structure in the pelvis and hip region that cause strain or compression on the nerves in the area. Often patient’s descriptions of pain can be the first sign with complaints of ‘burning’, ‘sharp’, or changes in sensation. Evaluation for changes in reflexes and motor function are helpful. Other signs of nerve entrapment are tenderness to palpation and reproduction of pain with movements that elongate the nerve. Medical management to confirm diagnosis include nerve blocks, and diagnostic imaging, and nerve conduction velocity tests.

The authors of this study focused on hip, so this blog focuses on sciatic and pudendal nerve entrapment in the athletic population. Nerve entrapment occurs when the normal slide and glide is limited. That can be from any structure in the pelvis and hip region that cause strain or compression on the nerves in the area. Often patient’s descriptions of pain can be the first sign with complaints of ‘burning’, ‘sharp’, or changes in sensation. Evaluation for changes in reflexes and motor function are helpful. Other signs of nerve entrapment are tenderness to palpation and reproduction of pain with movements that elongate the nerve. Medical management to confirm diagnosis include nerve blocks, and diagnostic imaging, and nerve conduction velocity tests.

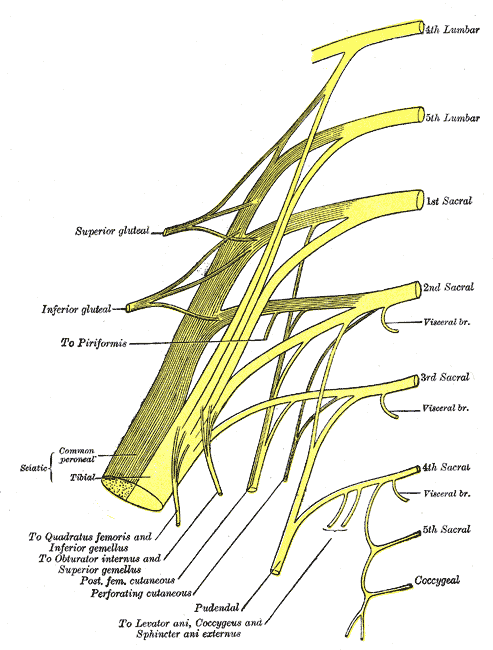

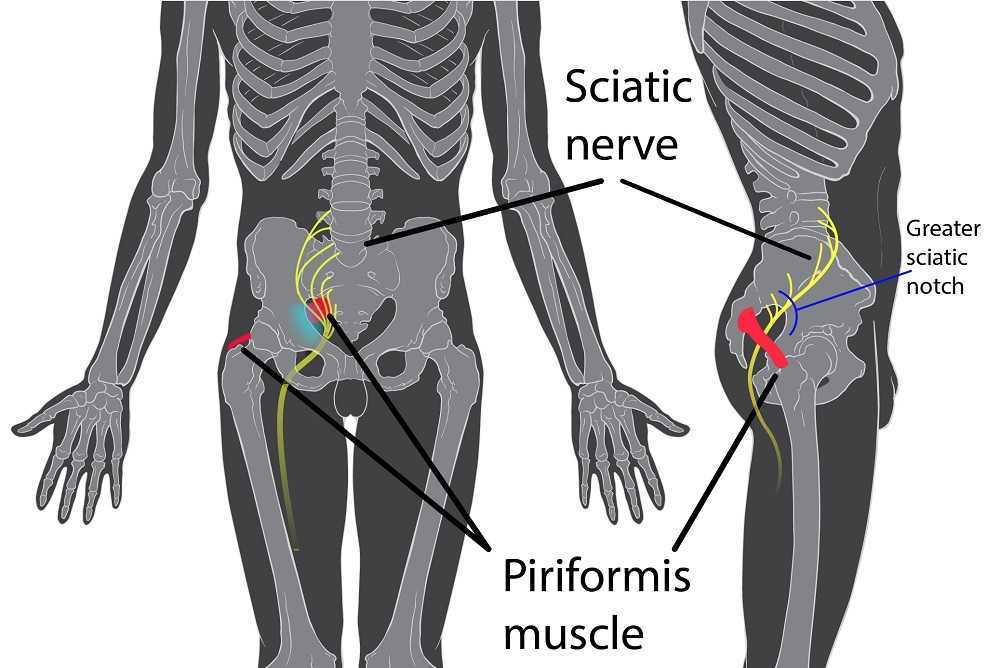

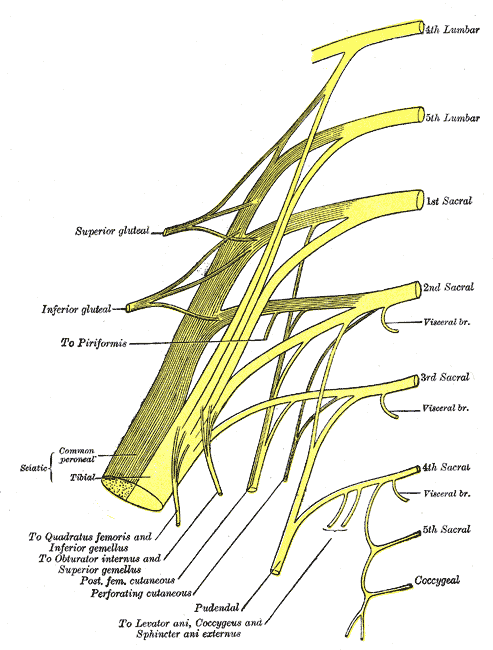

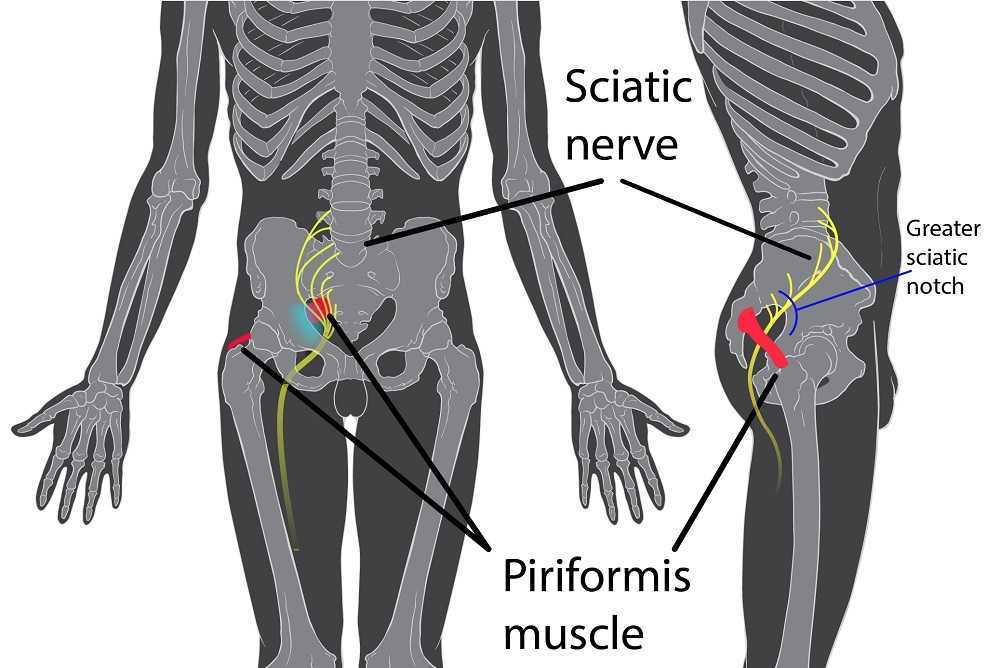

Specific locations of pain can help determine where the nerve is being squished. The sciatic nerve (L4-S3) can be entrapped as it passes between the piriformis and deep hip rotators. This often presents with a history of trauma to the gluteal area and limited sitting tolerance (>30 minutes). As the sciatic nerve moves down it can have ischiofemoral impingement, when the nerve gets compressed between lateral ischial tuberosity and greater trochanter at level of quadratus femoris muscle. This will often present as pain during mid- to terminal-stance during walking. Then, once the sciatic nerve clears the pelvis it can become entrapped by the proximal hamstring. There can be hamstring trauma in the history, and possible partial avulsion or thickening of the hamstring may entrap the sciatic nerve.

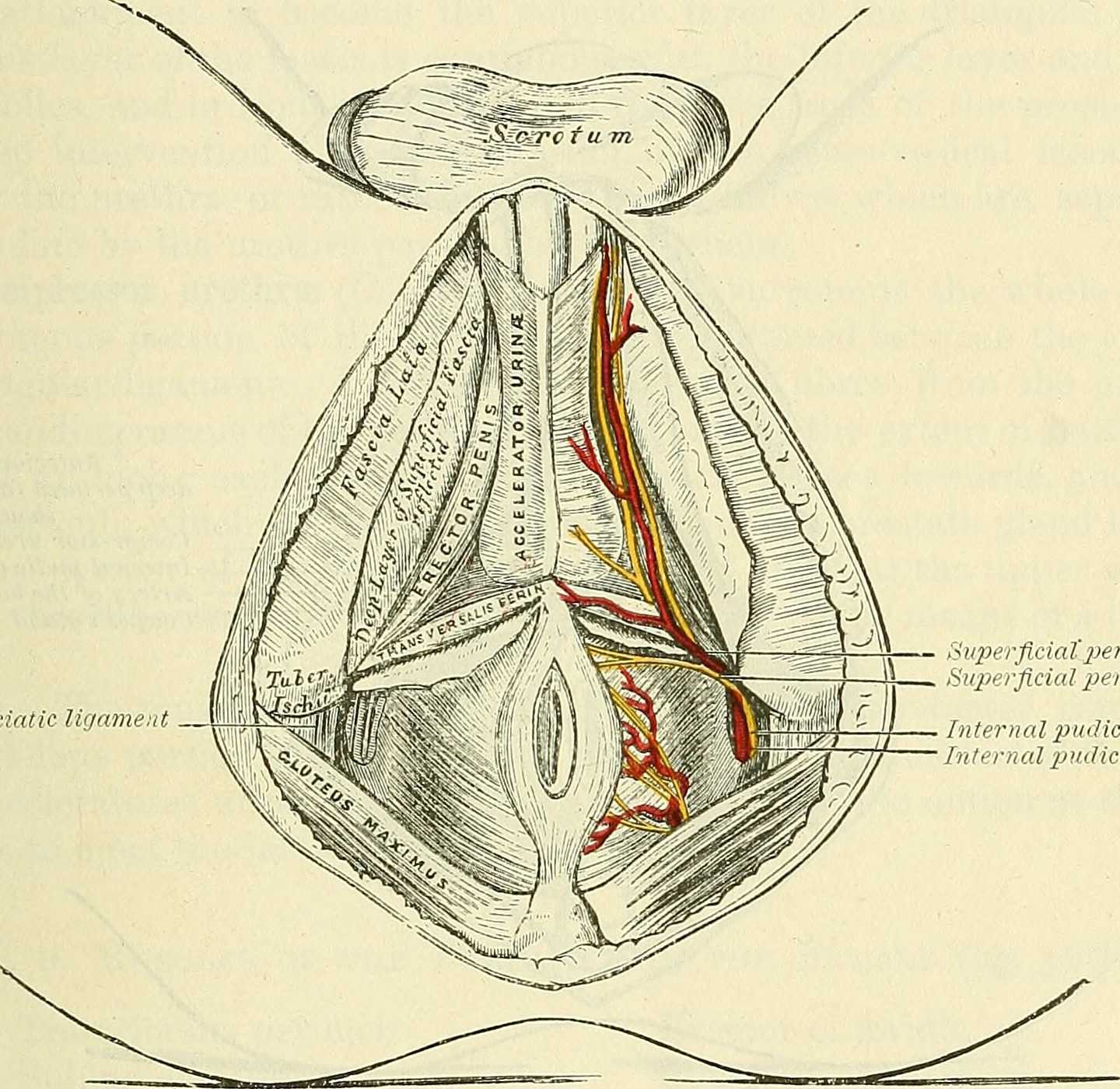

The pudendal nerve (S2-S4) can become entrapped in several areas and symptoms often include pain medial to the ischium and can include genital regions for all genders, perineum, and peri-rectal regions. The most common areas consist of the space between the posterior pelvic ligaments (sacrospinous and sacrotuberous) and the obturator internus muscle. History often includes bike riding, and a common complaint is pain with sitting, except a toilet seat.

Differential diagnosis for posterior nerves physical examination can include the following tests:

Sciatic Nerve

- Seated palpation: where the clinician palpates the subgluteal space (between sacrum and deep hip rotators), ischial tuberosity and hamstring attachment, and in the area medial to ischial.

- Seated piriformis stretch - involved lower extremity is adducted and internally rotated while palpating posterior hip region.

- Active piriformis - resisted lateral abduction and external rotation while palpating posterior hip region.

- Ischiofemoral impingement: the involved is placed in extension with adduction and external rotation

- Active knee flexion: this test is done seated with knee at 30° and 90° flexion. Clinician palpates ischial canal while providing knee flexion resistance for 5 seconds in both positions.

Pudendal Nerve

- Palpation around sciatic notch, region medial ischium

- Internal palpation for obturator internus tenderness

- Internal palpation of alcocks canal

Consertative treatment including physical therapy can be helpful. Manual therapy including nerve glides and soft tissue mobilization. Nerve mobilizations require anatomical nerve pathway knowledge. Mobilizing the nerves is thought to improve blood flow within and around the nerve, decrease adhesions, and also may affect central sensitivity. Soft tissue mobilization is geared towards positively affecting scar tissue and encouraging movement that may be restricting neural movement.

Therapeutic exercises for strengthening and stretching are also helpful, however use caution to avoid aggressive stretching as it may aggravate nerves. Exercises to promote load transfer through the pelvis and lower extremities can be helpful. The authors also suggest lower extremity passive PNF (proprioceptive neurofacilitation) diagonal movements. The authors also suggest aerobic conditioning, cognitive behavioral therapy, and for the chronic pelvic pain population, pelvic floor muscle training that does not provoke symptoms.

When conservative treatment including injections produces limited results, surgical treatments are often the next step. Often surgeries where the nerves are decompressed, neurolysis, or removed, neurectomy can be helpful.

To learn more nerve assessment and treatment techniques, join Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC in her course Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment in Tampa, FL this December 6-8, 2019!

Martin R, Martin HD1, Kivlan BR 2.Nerve Entrapment In The Hip Region: Current Concepts Review.Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Dec;12(7):1163-1173.

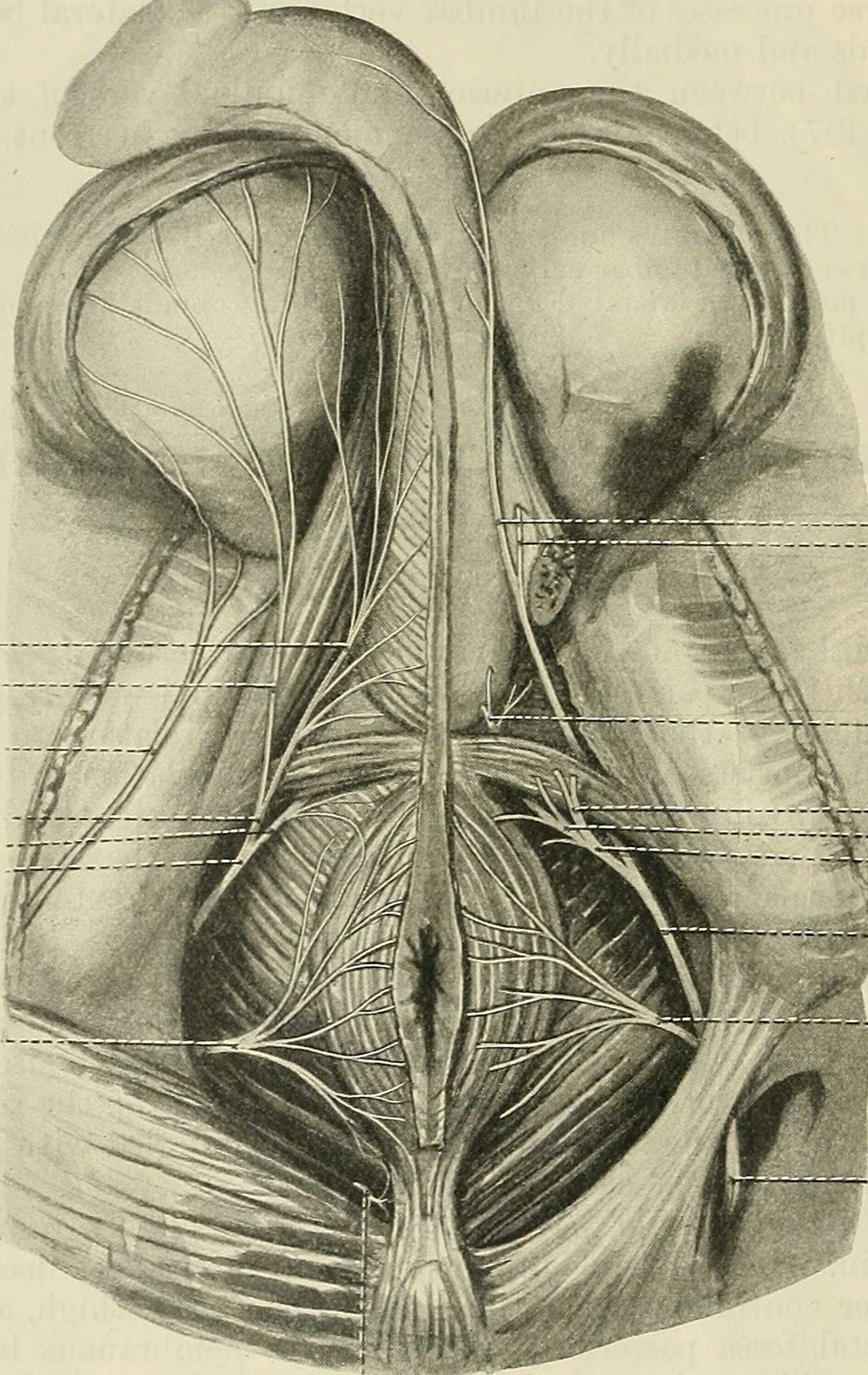

Men who present with chronic pelvic pain frequently have symptoms referred along the penis and into the tip of the penis, or glans. Symptoms may include numbness, tingling, aching, pain, or other sensitivity and discomfort. The tip of the penis, or glans, is a sensory structure, which allows for sexual stimulation and appreciation. This same capacity for valuable sensation can create severe discomfort when signals related to the glans are overactive or irritating. One of the most common complaints with this symptom is a level of annoyance and distraction, with level of bother worsening when a person is less active or not as mentally engaged with tasks. Wearing clothing that touches the tip of the penis (such as underwear, jock straps, jeans, or snug pants) may be limited and may worsen symptoms. When uncovering from where the symptoms originate, the culprit is often the dorsal nerve of the penis, which is sensible given that the glans is innervated by this branch of the pudendal nerve. If we consider this possibility (because certainly there are other potential causes) we find that there are many potential sites of pudendal nerve irritation to consider. First, let’s visualize the anatomy of the nerve.

Following the usually accepted descriptions of the dorsal nerve, we know that it is a terminal branch of the pudendal nerve that primarily is created from the mid-sacral nerves. This can lead us to include the lumbosacral region in our examination and treatment, yet in my clinical experience, there are other sites that more often reproduce pain in the glans. As the dorsal nerve branches off of the pudendal, usually after the location of the sacrotuberous ligament, it passes through and among the urogenital triangle layers of fascia where compression or irritation may generate symptoms.

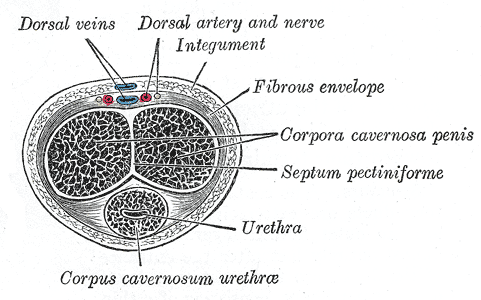

As the nerve travels towards the pubic bone, it will pass inferior to the pubic bone, a location where suspensory ligaments of the penis can be found as well as pudendal vessels and fascia. This is also a site of potential compression and irritation, and palpation to this region may provide information about tissue health. Below is a cross-section of the proximal penis, allowing us to see where the pudendal nerve and vessels would travel inferior to the pubic bone.

As the dorsal nerve extends along either side of the penis, giving smaller branches along its path towards the glans, the nerve may also be experiencing soft tissue irritation along the length of the penis or even locally at the termination in the glans.

Palpation internally (via rectum) or externally may be a part of the assessment as well as treatment of this condition. Oftentimes, tip of the penis pain can be reproduced with palpation internally and directed towards the anterior levator ani and the connective tissues just inferior to the pubic bone. It may be difficult to know if the muscle is providing referred pain, or if the nerve is being tensioned and reproducing symptoms, however gentle soft tissue work applied to this area is often successful in reducing or resolving symptoms regardless of the tissue involved. In my experience, these symptoms of referred pain at the tip of the penis is often one of the last to resolve, and the use of topical lidocaine may be helpful in managing symptoms while healing takes place. Home program self-care including scar massage if needed, nerve mobilizations, trunk and pelvic mobility and strengthening, and advice for returning to meaningful activities can play a large role in resolution of pain in the glans.

If you would like to learn more about treating genital pain in men, consider joining me in Male Pelvic Floor: Function, Dysfunction, & Treatment. The 2018 courses will be in Freehold, NJ this June, and Houston, TX in September.

Recently, I had a patient present to my practice with unretractable vaginal pain that was causing her quite a bit of suffering. Peyton (name changed) had been referred by a local osteopathic physician. For around a year, she had increasing severe vaginal pain. There was no history of assault, trauma, fall, or injury around the time of onset of symptoms. However, she had a kidney infection that caused back pain in the month prior to her pain onset.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

Objective findings revealed normal range of motion in her spine with the exception of limited forward flexion (feeling of back tightness at end range). Hip screening was negative for FABERS, labral screening or capsular pain patterns. General dural tension screening was positive for increased lower extremity and sensation of back tightness with slump c sit. Neural tension test was positive bilaterally for sciatic, R genitofemoral, L Iliohypogastric and Ilioinguinal nerves, and bilateral femoral nerves. Patient had a mild, barely perceptible lumbar scoliosis, and development of bilateral lower extremities and feet was symmetric and normal.

Because of the child’s age, we did not perform internal vaginal exam or treatment. This required treating the nerves that supply the vaginal area. All treatments were done with the patient’s mother present with both consent of the child and the mother.

For treatment, we started with the three inguinal nerves (Ilioinguinal, Iliohypogastric and genitofemoral) because of their relationship with the kidney (symptoms came on after kidney infection) as well as the correlation with the patient’s most limiting symptoms (genital pain). We cleared the fascia along the lumbar nerve roots, the lateral trunk fascia, the psoas, the inguinal region, the entrapments along the kidney and psoas, the inguinal rings and canal, and worked on neural rhythm (these techniques can be learned at the Pelvic Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment class that I will be teaching later this month).

Over the next weeks, we used similar treatments for the sciatic nerve, femoral nerve, pudendal, and coccygeal nerves. We noted that the patient had an area of restricted tissue along her coccyx that was adhered, and her symptoms had some correlation with tethered cord. We did lots of soft tissue work along the coccyx and working along the coccyx roots, including some internal rectal work. We also did fascial and visceral work in the bladder region, as well as in the lumbar and sacro-coccygeal region.

Peyton’s referring physician and mother were notified of findings and possible tethered cord symptoms (leg weakness and pain, bladder symptoms, delayed nocturnal continence). The patient’s family felt she was getting better and was not interested in any kind of surgical intervention, and her physician also felt that with our progress, he was not interested in exploring that referral, unless the family was interested.

After just 4 treatments Peyton was no longer having any vaginal symptoms and was emptying the bladder normally. After 8 treatments Peyton was reporting no more lumbar pain or lower extremity symptoms, and follow up treatments were reduced to once a month. The patient was given a home program of neural flossing in a small yoga program we recorded on her mother’s phone. We had her mother work on the small area that remained adhered along patient’s tailbone. The area is much smaller, but it reproduces some pelvic pain for the patient, so we are carefully and slowly working along this area because of some of the global neural sx it produces.

The patient’s mother reports she is more active, no longer complaining of leg or vaginal pain. The patient has less generalized anxiety and she is able to void fully. When the pt grows in height, there is a return in some symptoms, likely due to increased neural tension. So, we have the family on standby and when the patient grows, they come back in for 2 visits, which is usually enough to get the patient back to her new baseline.