Did you know that Ramona Horton is going to be speaking at HWConnect in March? Her lecture is titled, “The Do Not Miss List: What many pelvic rehab therapists overlook." I don’t know about you, but we’re pretty excited to hear what she has to say and to learn from the best!

So, who is Ramona C. Horton MPT, DPT?

Ramona completed her graduate training in the US Army–Baylor University Program in Physical Therapy in San Antonio, TX. She exited the army at the rank of Captain and applied her experience with the military orthopedic population in the civilian sector as she developed a growing interest in the field of pelvic dysfunction and received her post-professional Doctorate in Physical Therapy from A.T. Still University in Mesa, AZ. In 2020, Ramona received the prestigious Academy of Pelvic Health Elizabeth Noble Award for her contributions to the field of pelvic health.

Ramona is the lead therapist for her clinic's pelvic dysfunction program in Medford, OR where her practice focuses on the treatment of urological, gynecological, and colorectal issues. Ramona has completed advanced studies in manual therapy with an emphasis on spinal manipulation, and visceral and fascial mobilization.

Not only is Ramona Horton, MPT, DPT speaking at HWConnect 2025 in March, but she has also developed and instructs the Visceral and Fascial Mobilization Course Series for Herman & Wallace. If you haven’t taken a course from Ramona or heard her speak, then we highly recommend that you do!

The top 3 reasons to sign up for a course with Ramona Horton are:

1. Understand the true function and mechanisms of manual therapy.

Manual therapy is presented as a concept and technique that does NOT “release” tight or bound fascia based on the skill or magic hands of the practitioner. The issue is not in the tissue, if the tissue is tight, it’s tight because the brain is keeping it that way. Muscles are marionettes, and the brain is the puppet master. Manual therapy utilizes the fascial system to access the nervous system. In other words, having a conversation with the brain over the tissue that it appears to be protecting while trusting that the homeostatic mechanism is functioning in the body. If this is done in a non-threatening manner, the brain will normalize the tissue it is holding and guarding.

2. Add a whole host of new tools to your practitioner toolbelt.

The myofascial course teaches basic screening techniques that will point you in the right direction toward finding where the body is protecting, not where symptoms are being expressed. You will learn a variety of techniques to approach different fascial layers including direct and indirect fascial stacking for superficial nerves within the panniculus, muscular, and articular restrictions, as well as indirect technique of positional inhibition for trigger points. In addition, the science behind basic neural mobilization, instrument-assisted fascial mobilization, and fascial decompression (cupping) are presented.

3. Learn more about fascia, its origins, and its functions.

Fascia is EVERYWHERE throughout the body; it is the ubiquitous connective tissue that holds every cell together much like the mortar in a brick wall, in addition to cells, it connects every system in the body. Fascia contains a vast neurological network including nociceptors, mechanoreceptors, and proprioceptors just to name a few. The fascial system has multiple layers within the body: starting at the panniculus which blends with the skin, the investing fascia surrounding muscles and forming septae, the visceral fascia which is by far the most complex and the deepest layer of fascia, the dura surrounding the central nervous system extending to the peripheral nerves. All fascial structures, regardless of layer or location have their origin in the mesoderm of early embryologic development. The myofascial course presents evaluation and treatment techniques for three of the four fascial layers while the three visceral courses address the complex visceral fascial layer.

Ramona Horton's Mobilization Series 2024 Course Schedule

The Mobilization courses are available in satellite and self-hosted formats. PLUS Ramona is going on the road this year and will be teaching directly from different satellites for each course. Find out more on the Visceral and Fascial Mobilization Course Series home page. Satellite locations can be found on the main course page and may change, be added or removed, for future course events.

Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremity - Satellite Lab Course

April 4-6

Bradenton FL

Medford OR

Milwaukee WI

Novato CA

St. Petersburg FL

Torrance CA

Self-Hosted

Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Gastrointestinal System - Satellite Lab Course

March 7-9

Appleton WI

Lansing MI

Nashville TN

Portland ME

Tampa FL

Torrance CA

Tuscon AZ

Self-Hosted

June 27-29

Milwaukee WI

St. Petersburg FL

Sellersville PA

Self-Hosted

Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System - Satellite Lab Course

January 31-February 2

Fort Lauderdale FL

Medford OR

Tampa FL

Torrance CA

Wichita KS

Self-Hosted

May 16-18

Atlanta GA

Bradenton FL

Philadelphia PA

Self-Hosted

November 14-16

Milwaukee WI

Stevens Point WI

Self-Hosted

Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Reproductive System - Satellite Lab Course

October 17-19

Milwaukee WI

Omaha NE

Torrance CA

Tuscon AZ

Self-Hosted

How does it assist with return to activity?

I recently had a conversation with a sports medicine physician with whom I have shared patients for the past 20 years. He is one of the ‘OG’ physical medicine and rehab physicians in my area, and he has always been a huge advocate for rehab therapies. This physician has spent countless hours in rehab gyms sharing with and learning from physical therapists.

He reached out to me about a mutual patient with a three-year history of pelvic girdle pain that was limiting their activities, including sitting and cycling. This patient was referred to me 6 months ago after plateauing with his sports medicine PT and interventional pain medicine physicians. They had undergone interventions including medications, injections, PT, and group therapy CBT for persistent pain. However, pelvic rehab shifted the needle for this patient, and the physician wanted to learn more about what helped.

Now, this patient has had amazing care already. They were seeing an awesome and skilled sports medicine PT. The patient was engaged and consistent with their self-care program including strengthening, movement, posture, breathing, stretching, bike fit, and activity modification.

What I brought to the table was a focused approach to the pelvic floor region – that was what was missing. We focused our sessions on education about the pelvic floor region including the functional role of the myofascial tissues of the perineum and rectal fossa specifically in the protection of the neurovascular tissues in the perineum, manual therapy, progressive exercise, and return to activities.

When the MD and I reviewed this case, our conversation revolved around manual therapy and how it helps our patients. He wanted to understand how we decide what interventions to utilize to help patients in their recovery. He specifically wanted to understand when to touch and when to focus on strength/movement only. My answer was simpler than that. I felt that most of our patients needed both throughout their course of care.

We discussed that one of the main things for this patient was that they did not realize that myofascial tissues attached in the perineum could impact their sitting. More specifically, they did not realize that there were muscles located in the pelvic region that they could engage, relax, lengthen, and strengthen. Upon assessment, this patient had decreased pliability of the tissues in the urogenital triangle and rectal fossa which contributed to less tolerance to sitting, likely due to compression of neurovascular structures in the perineum. With manual therapy, we were able to increase the pliability of those tissues and increase the patient’s awareness of the myofascial tissues. We also spent time in our sessions having the patient learn to engage, release, and lengthen the PF muscles.

With manual therapy, the patient became aware of those muscles and with tactile cues learned how to actively engage with those muscles. After about 4 weeks, the patient began gradually returning to sitting and to time on the bike. We continued manual therapy while the patient built tolerance and confidence to sitting on a chair and a bike saddle.

I utilized manual therapy to assist the patient with gaining awareness of the pelvic floor region, and we continued these manual therapy sessions to assist with recovery from increasing sitting. Ultimately, the patient could return to cycling and sitting without limits. The patient also learned how to self-manage with their already established self-care and we added focused pelvic floor region stretching, recovery, and awareness.

The Physician and I discussed the commentary by Short et al 2023 about manual therapy in return to sport and recovery. The commentary has a great statement supporting manual therapy usage: “The benefits of manual therapy, which includes building therapeutic alliance via touch, improving function via safe, cost-effective short-term pain modulation and facilitating education and exercise to be more impactful when they are limited less by pain and anxiety” for return to activity. In pelvic health rehab practice by using manual therapy, we can help the patient become aware of a part of their body, decrease apprehension to touch and pressure to the area, and then focus on the patient's self-care to promote long-term recovery and self-reliance.

This fostered further discussion with the MD about mechanical touch and how it affects the body. Short et al 2023 further stated “When a therapist provides a manual intervention, a mechanical stimulus is applied upon an athlete and produces input into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord…….initiating a multi-factorial cascade of neurophysiologic effects stemming from the nervous system. Both the peripheral and central nervous system provide signal pathways that induce responses throughout the body. These include neuromuscular (i.e., muscle activity), autonomic (i.e., heart rate, cortisol), endocrine (opioid) pain modulatory, and non-specific (context, beliefs fear, expectations, etc.) responses.” Put in these terms the physician had a better understanding of the multifactorial level that physical touch can assist with patient recovery.

Utilizing manual therapy techniques/therapeutic touch is foundational to helping patients become aware of their patterns of movement or stiffness and parts of their body. In Manual Therapy for the Abdominal Wall, scheduled on October 20th, 2024, we discuss these concepts and apply manual therapy techniques to the abdominal wall. While for this class we utilize the abdominal wall to practice, the skills learned can then be applied throughout the body. This is a foundational class for anyone who wants to build their skills in manual therapy and then take those skills to further advance their patient care in any part of the body. We do discuss specific abdominal wall conditions such as abdominal wall post-surgical incisions and hernia, but we apply the basic manual therapy techniques to them that could then be applied anywhere in the body including the perineum and rectal fossa.

Reference:

Short S, Tuttle M, Youngman D. A Clinically Reasoned Approach to Manual Therapy in Sports Physical Therapy. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2023 Feb 1;18(1):262-271. doi: 10.26603/001c.67936. PMID: 36793565; PMCID: PMC9897024.

AUTHOR BIO:

Tina Allen, PT, PRPC, BCB-PMD

Tina Allen, PT, PRPC, BCB-PMD (she/her) has been a physical therapist since 1993. She received her PT degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her initial five years in practice focused on acute care, trauma, and outpatient orthopedic physical therapy at Loyola Medical Center in Illinois. Tina moved to Seattle in 1997 and focused her practice in Pelvic Health. Since then she has focused her treatment on the care of all genders throughout their life spans with bladder/bowel dysfunction, pelvic pain syndromes, pregnancy/ postpartum, lymphedema, and cancer recovery.

Tina Allen, PT, PRPC, BCB-PMD (she/her) has been a physical therapist since 1993. She received her PT degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her initial five years in practice focused on acute care, trauma, and outpatient orthopedic physical therapy at Loyola Medical Center in Illinois. Tina moved to Seattle in 1997 and focused her practice in Pelvic Health. Since then she has focused her treatment on the care of all genders throughout their life spans with bladder/bowel dysfunction, pelvic pain syndromes, pregnancy/ postpartum, lymphedema, and cancer recovery.

Tina’s practice is at the University of Washington Medical Center in the Urology/Urogynecology Clinic where she treats alongside physicians and educates medical residents on how pelvic rehab interventions will assist clients. She presents at medical and patient conferences on topics such as pelvic pain, continence, and lymphedema. Tina has been faculty at Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute since 2006. She was the physical therapist provider for the University of Washington on a LURN Multi-Center study for Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome treatment with physical therapy techniques. Tina was also a co-investigator for a content package on pain education for the NIDA/NIH on the treatment of pelvic pain.

This week Ramona Horton sat down with Holly Tanner to discuss manual therapy and her course Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremity. The following is an excerpt from her interview.

What do we really know about manual therapy? We have decent evidence that shows that asymmetry matters. The tenet of the myofascial course is an osteopathic tenet called ARTS:

- Asymmetry

- Restriction of Mobility

- Tissue Texture Changes

- Sensitivity

The whole myofascial course is designed around looking for ARTS. When you find the asymmetry within the myofascial system then that’s where you direct your efforts and energy.

Often patients have already tried breathing, yoga, medication, etcetera – and it’s the manual therapy piece that they often have not had. It’s not that uncommon for me to be someone’s second or third therapist. Some patients may have tried some type of manual therapy but it was more things like ischemic compression where the problem was that the manual therapy was triggering nociception.

So in the myofascial course, we start with ARTS but we also have an idea where we flip ARTS on its head and we go to STAR. In STAR, you take sensitivity and put it at the top of your list. That becomes the highest portion in your paradigm. Then we use simple techniques that are not non-nociceptive. Indirect technique versus direct technique, such as something as simple as positional inhibition.

The whole idea of the myofascial course is to teach people to think and problem solve. Then have a very broad spectrum way of you find an inner articular issue where this joint is moving and this one is not. Learn to not chase the booboo. Just because it hurts on the right doesn’t mean that you’re going to treat the right. It might hurt on the right because there is a hypo-mobility on the left. Let’s treat where the brain is protecting the tissue, and holding, and guarding the tissue. Trust in the belief that the body is a self-righting mechanism. The body will then normalize itself.

In manual therapy, our job is to get the body moving like it's supposed to. It’s not to fix the ‘booboo.’ The issue is not in the tissue. If the tissue is tight, it’s tight because the brain is keeping it that way. The way I teach manual therapy is the fascial system gives us access to the nervous system. By utilizing the fascial system in a non-nociceptive manner, what we’re really doing is just having a conversation with the brain. We’re not fixing the tissue. That’s the whole premise of the course - to get people to understand and change their thinking and their paradigm to ask what the brain is protecting and utilizing the fascial system.

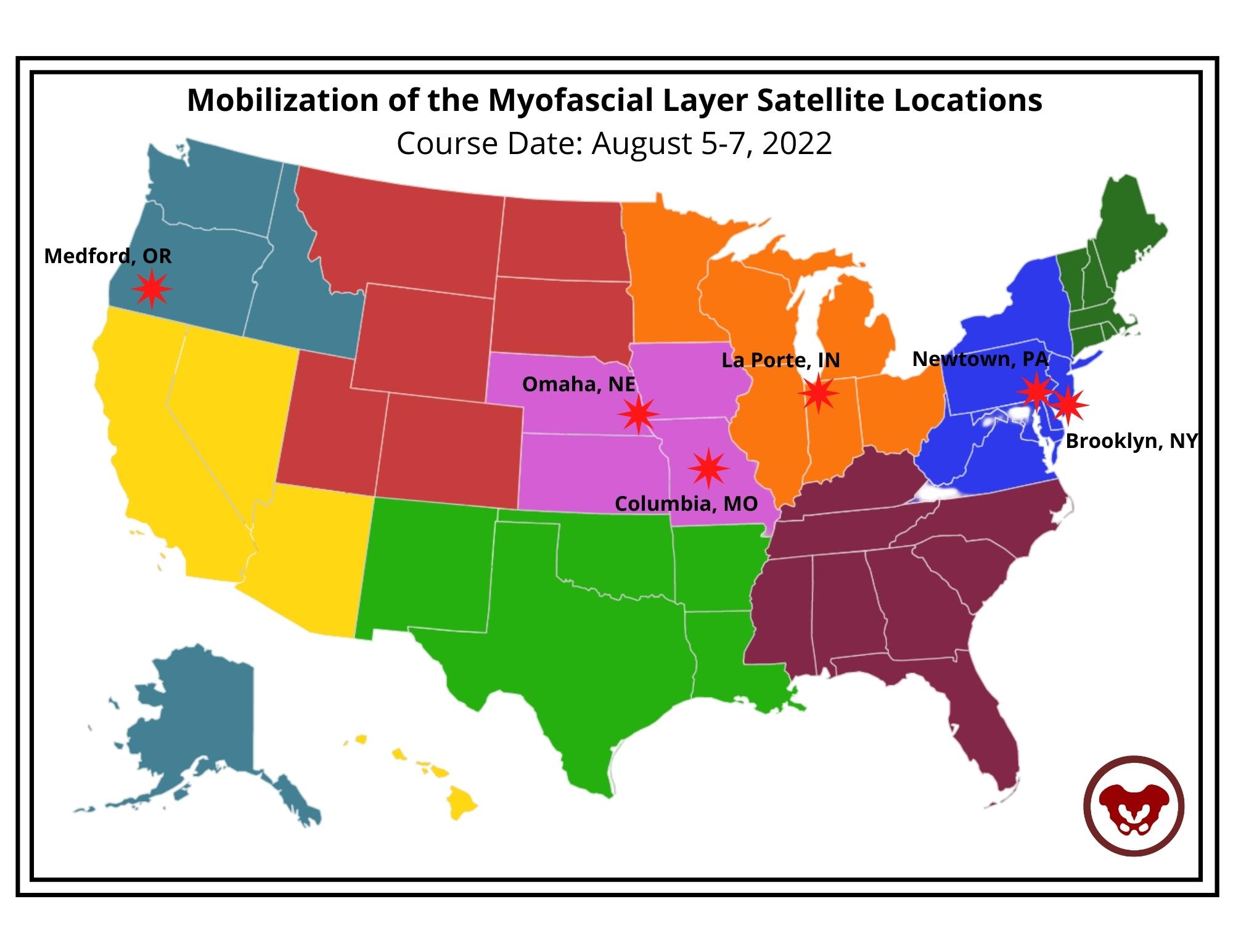

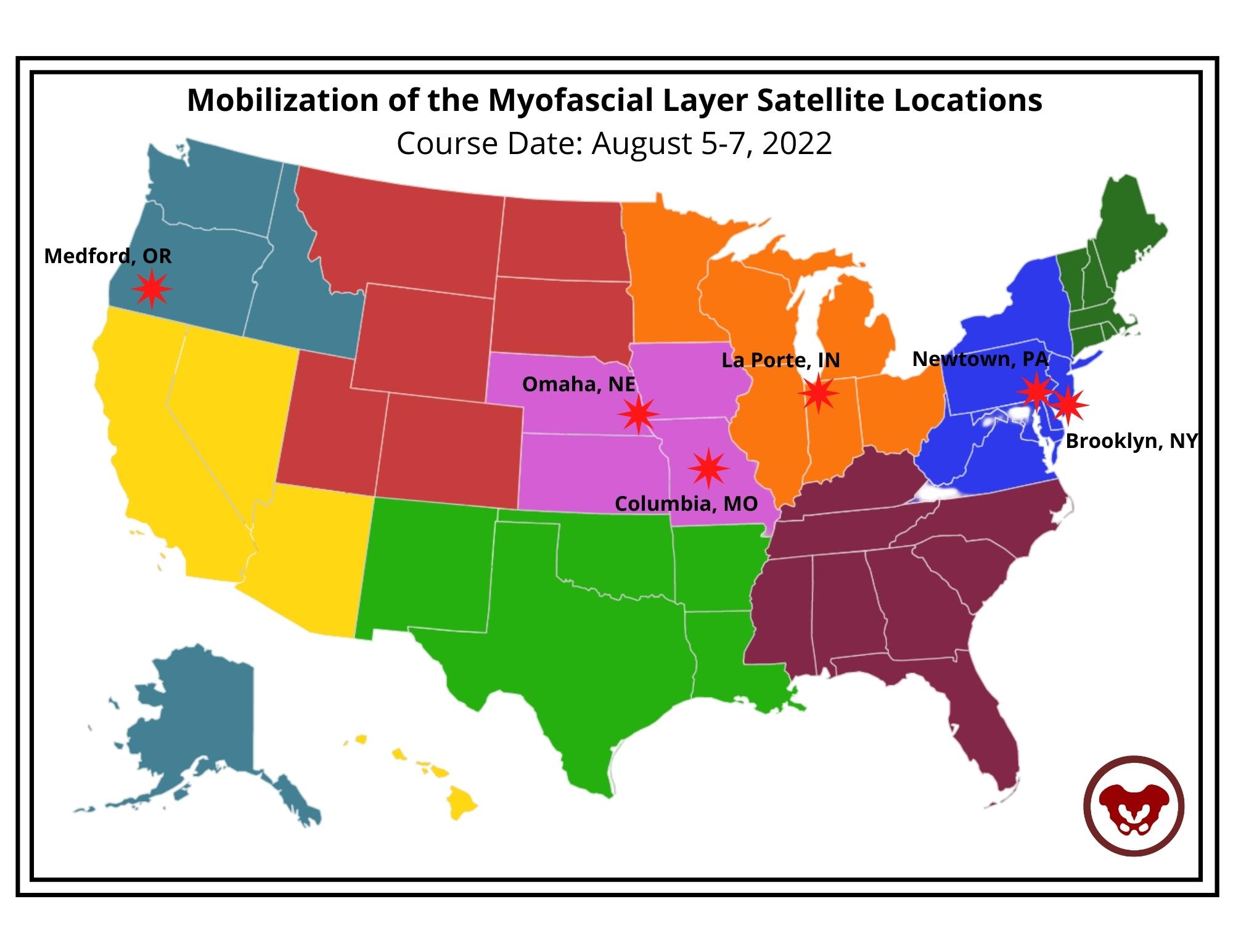

Course Date: August 5-7, 2022

- Self-Hosted - for groups of at least 2 qualified practitioners.

Manual Therapy for the Abdominal Wall allows practitioners to review how everything interplays within the myofascial system and apply specific techniques. These techniques include how to assess the tissue for mobility, how to treat tissues that are restricted in the abdominal wall, and how to treat scar tissue. How do we help somebody who can’t lay flat because their abdominal wall has become restricted for so long because of possible pain? Possibly due to surgery. Possibly due to fear. How do we help those patients get back to function?

Over the past 10 plus years of teaching the pelvic series with Herman & Wallace, Tina Allen noticed that for some of the participants there was a gap in confidence in palpation skills and treatment techniques applied to the pelvic floor region. For most, it’s confidence in where they are and what they are feeling on the patient. Manual Therapy for the Abdominal Wall came out of wanting to fill that gap. This course is really about taking some of those skills and then applying them to the abdominal wall.

Abdominal pain can arise from many origins including abdominal scars, endometriosis, IC/PBS, and abdominal wall restrictions that impact pelvic girdle dysfunction. An older study, back in 2007 by Geoff Harding focused on back, chest, and abdominal pain and whether it was spinal referred pain and employed manual therapy as part of his treatments for his case studies. Harding found that “More specific treatment of the origin of the pain may then include manual therapy, including mobilization (gentle rhythmic movement), … applied to the affected segment can be very effective in reducing movement restriction – and pain. These simple treatments were used in all three case studies to good effect.” (1)

This research was supported by Rice et al. in 2013 when their research on non-surgical treatment of adhesion-related small bowel obstructions showed that “those patients who underwent the manual therapy demonstrated increased range of motion … and an early return to normal activities of daily living simply enhanced the benefits.” (2) Manual therapy has no recovery time and allows patients to recover and participate in daily activities while promoting the return of normal tissue function, range of motion, and increased blood flow.

Tina Allen explains that manual therapy is about “asking for permission to touch and using our hands to help the patient integrate into their system again. The patient may not realize that they’ve been holding, that there is tension or rigidity in the tissues.” Tina continues to share that “for me, manual therapy fits in to help folks realize, or feel, what’s happening in their body again. And then allowing them to make that change. I use manual therapy to allow a patient to move better. To become more aware in their body.” The full interview with Tina can be viewed below or on the Herman & Wallace YouTube Channel.

Manual Therapy for the Abdominal Wall is a beginner-level class and is filled with practitioners just beginning their pelvic floor journey through experienced clinicians taking the course to learn something new. The techniques instructed by Tina Allen are immediately applicable in the clinic. Course dates for 2022 include:

References:

- Harding G, Yelland M (2007). Back, chest, and abdominal pain. Australian Family Physician, 36(6), 422-429.

- Rice, A. D., King, R., Reed, E. D., Patterson, K., Wurn, B. F., & Wurn, L. J. (2013). Manual Physical Therapy for Non-Surgical Treatment of Adhesion-Related Small Bowel Obstructions: Two Case Reports. Journal of clinical medicine, 2(1), 1–12.

The hip flexor muscles include the Iliopsoas group (Psoas Major, Psoas Minor, and Iliacus), Rectus Femoris, Pectineus, Gracillis, Tensor Fascia Latae, and Sartorius. When the hip flexors are tight it can cause tension on the pelvic floor. This can pull on the lower back and pelvis as well as change the orientation of the hip socket, lead to knee pain, foot pain, bladder leakage, prolapse, and so much more. The ramifications of iliacus and iliopsoas dysfunctions are discussed in Ramona Horton's visceral course series:

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Gastrointestinal System

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia - The Urinary System

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia - The Reproductive System

You can also learn about this in a contemporary and evidence-based model with Steve Dischiavi in his Sacroiliac Joint Current Concepts and Athletes & Pelvic Rehabilitation remote courses.

A common issue with the iliacus and hip flexors is that they can shorten over time due to a lack of stretching or a sedentary lifestyle. When this happens, the muscle adapts by becoming short, dense, and inflexible and can have trouble returning to its previous resting length. A muscle that resides in this chronic contraction can become ischemic, develop trigger points, and distort movement in the body.

If you are treating patients with pain in their lower abdomen, sacroiliac joint, or that wraps around the lower back and buttocks, it could be because the hip flexors are tight. Traditional testing performed by medical practitioners tends to come back negative as many tests do not evaluate soft tissue issues. The best way to diagnose these concerns is through assessment with skilled palpation and structural evaluation.

One assessment test used for the iliopsoas is discussed in the Athletes & Pelvic Rehabilitation course. This is the Thomas Test which measures the flexibility of the hip flexors. In this test, the patient is supine while flexing the unaffected, contralateral leg at the hip until lumbar lordosis disappears. The length of the iliopsoas is determined by the angle of hip flexion displayed by the patient. The test is positive when the patient is unable to keep their lower back and sacrum against the table, the hip has a posterior tilt (or hip extension) greater than 15°, or the knee is unable to meet more than 80° flexion. A positive test indicates a decrease in flexibility iliopsoas muscles.

Treatment plans for the iliacus and hip flexors include stretching. An example includes the hip extension stretch or other active isolated stretches. Manual therapy, including trigger point release, can be used in conjunction with stretching to help muscle adhesion and release muscle tension. As with all treatment, the practitioner should discuss the risks, benefits, and treatment options, and obtain consent with patients. Prior to proceeding with manual therapy treatment make sure to establish a pain scale, assess the patient's range of motion and strength, and (if needed) perform the appropriate neurologic testing.

To learn more about manual therapy options for the visceral fascia, join Ramon Horton in her Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia Satellite Lab Course Series (multiple satellite locations available):

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Gastrointestinal System - October 15-17, 2021

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System- September 17-19, 2021

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Reproductive System - October 1-3, 2021

To learn more about treatment philosophies for the pelvis and pelvic floor and global considerations of how these structures contribute to human movement you can join Steve Dischiavi:

- Athletes & Pelvic Rehabilitation Remote Course - September 18-19, 2021

- Sacroiliac Joint Current Concepts Remote Course - August 21, 2021

The female sexual response cycle is more than physical stimulation. As pelvic therapists, we frequently find ourselves treating pelvic pain that has interrupted a woman’s ability to enjoy her sexuality and sensuality. As physical therapists, we focus on the physical limitations and pain generators as a way of helping patients overcome their functional limitations. However, many of us find that once many of the physical symptoms have cleared with pelvic floor and fascial stretching, our patients are still apprehensive to engage physically, or they are not able to derive pleasure. There is clearly a gap that needs to be bridged that goes beyond pain.

Last year I taught my class, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment. I was honored and astounded to have Dee Hartmann, PT in my class. For those of you who do not know Dee, she has been a champion of our field for a long time, and she has been instrumental in elevating physical therapy as a first line of treatment in pelvic pain through her work, international leadership, and representation in multiple organizations, including APTA SOWH, ISSVD, IPPS, NVA, ISSWSH, and as an editor for the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Last year I taught my class, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment. I was honored and astounded to have Dee Hartmann, PT in my class. For those of you who do not know Dee, she has been a champion of our field for a long time, and she has been instrumental in elevating physical therapy as a first line of treatment in pelvic pain through her work, international leadership, and representation in multiple organizations, including APTA SOWH, ISSVD, IPPS, NVA, ISSWSH, and as an editor for the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

In this manual nerve class, I was teaching how to treat the path of the genitofemoral nerve, which affects the peri-clitoral tissues and sensation. We also covered manual therapy approaches to decrease restriction in the clitoral complex and improve the blood flow response in this region. Dee was fascinated and looped me into what she had been working on for the past several years. She has been working as part of a company called Vulvalove with her partner, sex therapist, Elizabeth Wood on studying and teaching women how to recapture their sensuality. Immediately, we wanted to combine forces in some way to present a way to approach these issues. So, when Dee invited me to present with Elizabeth and her at the Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association (CSM) this year, I was humbled and excited to jump on board.

With improved tissue mobility in the clitoral and vaginal area, blood flow is able to improve through any previously restricted tissues. With any manual therapy or soft tissue work, it is expected that cutaneous circulation of blood and lymph will alter. In studies, a measure of this blood flow, VPA (Vaginal Pulse Amplitude) is higher in the arousal than the non-arousal state in women.4 “The first measurable sign of sexual arousal is an increase in the blood flow. This creates the engorged condition, elevates the luminal oxygen tension and stimulates the production of surface vaginal fluid by increased plasma”.5 Manual therapy can likely affect this.1,2. During our CSM talk, I will discuss the neurovascular anatomy and will have a brief video of manual techniques to enhance these pathways in my portion of the presentation.

In the 19th century, female orgasm and sensuality was believed to be more vaginal, but as the 20th century unfolded, understanding of the clitoral tissues improved. More recent research reveals the origin of female pleasure is more complex, involving the clitoris, vulva, vagina, and uterus.3 However, female response is more complicated than just anatomy below the waist.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is a measure of autonomic nervous system health and the ability to flux between sympathetic and parasympathetic states. Autogenic training and meditation or mindfulness have been shown in multiple studies to improve HRV. A study by Stanton in 2017 demonstrated that even one session of autogenic training can increase HRV and VPA (Vaginal Pulse Amplitude, a measure of arousal). In our talk at CSM, Dee will cover the role of autogenics and how to specifically and practically use our autonomic state to influence our perception and feeling of pleasure. Dee will also cover extensive clitoral anatomy to have a better understanding of how this intricate complex functions and is structured in women.

Elizabeth Wood, a former sex therapist who is now a sex educator, will then present on the arousal cycle and what can be done physiologically to prepare the arousal network for climax. Elizabeth will help us to better define and understand the roles of arousal, calibration, and exploring sensuality, including exercises to help a patient have a more fulfilling experience once the physical pain is resolved. As Elizabeth says, “Knowledge is an antidote to shame and an invitation to pleasure”.

If you will be at CSM, please come join us at the opening session, Thursday February 13 from 8am-10am (PH2540), “Now That The Pain Is Gone, Where’s the Pleasure”.

If you can’t make it to CSM, I hope to see you at one of my nerve classes, “Lumbar Nerve Manual Therapy and Assessment” this year in Madison, WI April 24-26 or Seattle, WA October 16-18 to further explore manual therapies to improve sensation and neural feedback loops and to continue this conversation!

1. Portillo-Soto, A., Eberman, L. E., Demchak, T. J., & Peebles, C. (2014). Comparison of blood flow changes with soft tissue mobilization and massage therapy. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20(12), 932-936.

2. Ramos-González, E., Moreno-Lorenzo, C., Matarán-Peñarrocha, G. A., Guisado-Barrilao, R., Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M. E., & Castro-Sánchez, A. M. (2012). Comparative study on the effectiveness of myofascial release manual therapy and physical therapy for venous insufficiency in postmenopausal women. Complementary therapies in medicine, 20(5), 291-298.

3. Colson, M. H. (2010). Female orgasm: Myths, facts and controversies. Sexologies, 19(1), 8-14.

4. Rogers, G. S., Van de Castle, R. L., Evans, W. S., & Critelli, J. W. (1985). Vaginal pulse amplitude response patterns during erotic conditions and sleep. Archives of sexual behavior, 14(4), 327-342.

5. Stanton, A., & Meston, C. (2017). A single session of autogenic training increases acute subjective and physiological sexual arousal in sexually functional women. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 43(7), 601-617.

“However, at present we are all aglow with views on visceral anatomy and medical colleges are wisely establishing chairs in this department which will result in much advancement.” -Fred Byron Robinson, 1891 (Cysts of the Urachus)

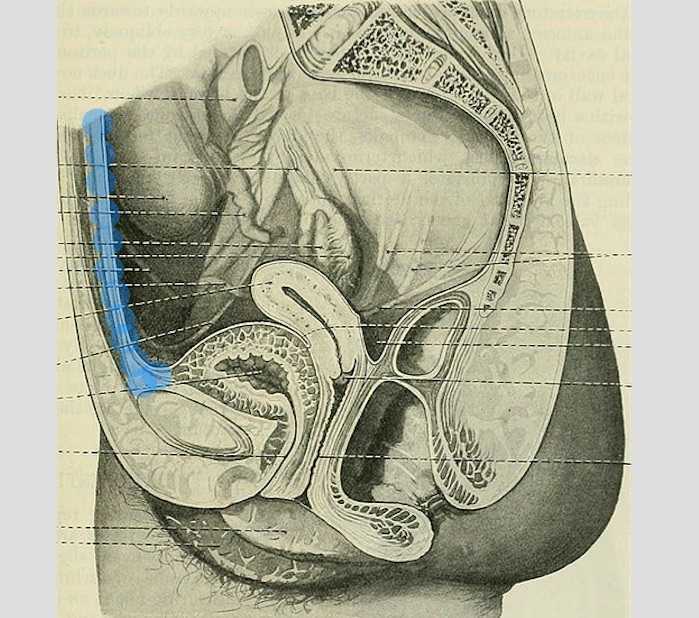

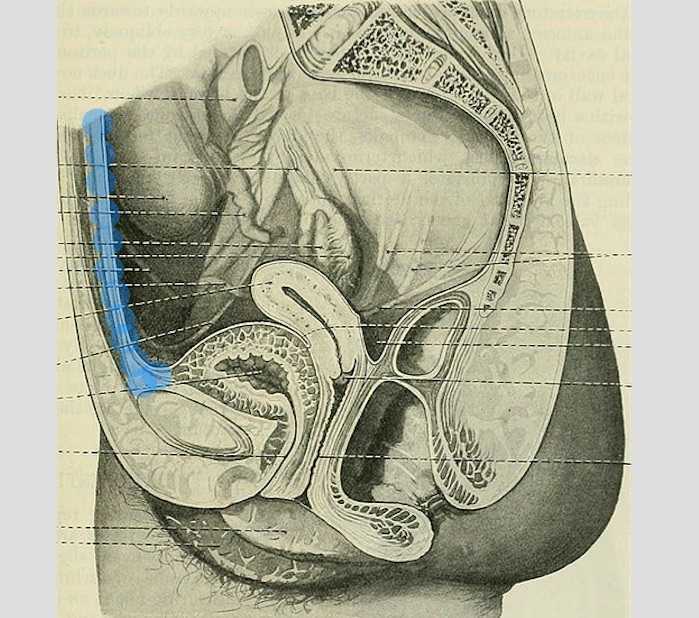

The above (fabulous) quote reminds us that many came before us who were equally excited by the study of anatomy. One anatomical structure that I know never appeared in my graduate anatomy courses is the urachus. The urachus is a structure that extends from the urinary bladder to the umbilicus (highlighted blue in the image). When investigating literature about this structure I was impressed to find publications about the urachus dating from the late 19th century.

It wasn’t until several years into my career as a physical therapist that I learned about the urachus, a structure attached to the bladder, and learned how this structure could create some rather dramatic symptoms when in dysfunction. I met a woman who was in her early 30’s and who had 6 months prior undergone a laparoscopic surgery with access just below the umbilicus. She presented to rehabilitation after seeing an urologist for severe pain that occurred towards the end of voiding. The pain was absent at any other time, but was so severe towards the latter half of emptying her bladder that she would double over in pain and “nearly pass out.” Investigation revealed a healthy, well-functioning pelvic floor and abdominal wall, but a reproduction of her severe pain with palpation to the midline between the umbilicus and the pubic bone. After grabbing some anatomy texts, I supposed that the urachus, having potentially been irritated by the laparoscopic approach, might experience a tensioning of the irritated tissue as the bladder contracted to empty. This theory appeared to hold some weight, as applying gentle manual therapy to the tissues, and teaching the patient some self-release techniques allowed her to resolve her symptoms entirely after 1-2 visits.

The urachus is formed in early development from the pre-peritoneal layer, and is described as vestigial tissue. It extends from the anterior dome of the bladder to the umbilicus, varying in length from 3-10 cm, with a diameter of 8-10 mm. There are 3 layers: an inner layer of transitional or cuboid epithelial cells surrounded by a layer of connective tissue. The remains of the urachus form the middle umbilical ligament which is a fibromuscular cord. A layer of smooth muscle that is continuous with the detrusor (smooth muscle of the bladder) makes up the outer layer. This continuity of tissue may help explain some of the clinical connections we see in patient symptoms. In the past year, I have met several patients for whom the urachus is the only tissue that reproduced their symptoms. I examined a male patient who reported urethral burning that occurred with both reset and activity. Unable to produce symptoms in any other location of the thoracolumbar spine, pelvic floor and walls, or abdomen, I palpated this structure to find that it reproduced the urethral burning. Another patient presented with a keloid c-section scar. She also described a sharp pain when the bladder was full. Treatment directed to the scar and along the midline resolved this pain, again with a couple sessions.

If you are interested in learning more about distinct anatomical connections that can help you explain (and treat) issues your patients present with, come and learn with us at the 3-day Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, and Treatment course offered four times over the 2019 and 2020 calendars. The role of the urachus in abdominopelvic dysfunction is just one of the many topics we explore. With lectures on sexual health, pelvic pain, prostate and urinary dysfunction, there is a broad range of topics and skills to offer for clinicians who are new to men’s heath and those who have been treating for years.

Begg, R. C. (1930). The Urachus: its Anatomy, Histology and Development. Journal of Anatomy, 64(Pt 2), 170–183.

Gray, H. (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Sterling, J. A., & Goldsmith, R. (1953). Lesions of Urachus which Appear in the Adult. Annals of Surgery, 137(1), 120–128.

Everyday we as pelvic rehab providers get to help patients achieve their goals by meeting them where they are and guiding them along.

A couple of months ago I had a new patient come in to see me who was seven months status post c-section delivery of her first child. She was referred to physical therapy because she could not tolerate anything touching her lower abdomen and she was also unsure of how to start exercising again including returning to her yoga practice. I remember reading her referral and thinking that this should be a simple evaluation and treatment session. What actually happened was a little different.

Her delivery hadn’t gone the way she planned, and she was not comfortable discussing it at our first session. This patient had not looked at or touched her c-section incision besides drying it off after her shower for the seven months since delivery. Her physician had made a referral to PT and to a counselor within three months of delivery to help support the patients’ recovery. The patient had not followed through with the PT referral until she had significant encouragement from her counselor and physician.

Initially the patient declined any observation or palpation of her abdomen so at our first session we focused on thoracic range of motion, general posture, and encouraged her to start touching her abdomen through her clothes, even if avoiding direct touch to the incisional region. The patient was agreeable with this starting point. At the second session the patient was willing to have me look at her abdomen and touch the abdomen but she declined direct palpation of the scar region. With simple observation I could see a scar that was closed and healing but also that was pulled inferior towards her pubic bone. She was not comfortable laying flat on the treatment table and had to be supported in a semi-recline throughout the session. She also described buzzing symptoms at the scar region when she reached her arms overhead.

We started some gentle desensitization techniques as would be used with a person that had Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) after an injury. I focused those treatments to the abdominal region but avoided the scar region. We focused her home program on breathing into her abdomen allowing some stretch and expansion of the abdominal region. Her home program also included laying flat for five minutes per day. I asked her to notice any general tension throughout her body during the day and attempt to change it and release it if able.

By the fourth session we where able to begin direct palpation and manual therapy techniques to the c-section scar and the whole abdominal region. The patient was apprehensive but agreed to proceeding with utilizing techniques as described by Wasserman et al2018 including superficial skin rolling, direct scar mobilization and general petrissage/effleurage of the abdomen and lumbothoracic region.

Over the next five sessions the patient was able to start wearing undergarments and pants that touched her lower abdomen. She was able to perform her own self massage to the region and began an exercise program including prone press ups, progressive generalized trunk strengthening, and return to her prior-to-pregnancy yoga practice.

Drawing on the techniques we learn from multiple sources, applying them to the lumbopelvic region, and helping our patients wherever the client is in their journey to wellness, is what inspires me to keep learning.

Techniques like this are taught in my 2-day Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist course. I specifically wrote this course so that pelvic rehab therapists that are looking for more techniques and/or more confidence in their palpation skills would have a weekend to hone those skills. We spend time learning anatomy, learning palpation skills, manual techniques, problem solving home programs and discussing cases. Check out Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist - Raleigh, NC - June 22-23, 2019 for more information and I hope to see you there.

Wasserman, J. B., Abraham, K., Massery, M., Chu, J., Farrow, A., & Marcoux, B. C. (2018). Soft Tissue Mobilization Techniques Are Effective in Treating Chronic Pain Following Cesarean Section: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 42(3), 111-119.

My name is Tina Allen. I teach a course called Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist. I developed this course in 2016 out of desire to help clinicians feel comfortable in their palpation and hands on skills.

My journey as a pelvic rehab therapist started with a patient whispering to me in the middle of a busy sports/ortho clinic gym; “is it normal to leak when you laugh”. I was treating her after her total hip replacement and my first question was “where are you leaking”? I was concerned that her incision was leaking, that she had an infection and it was beyond me to understand why it would happen when she laughed! I was 24 years old and 2 years out of PT school. Little did I know, that one whispered question would lead me to where I am today. I am in my 25th year as a PT and 20th year specializing in pelvic rehabilitation.

My journey as a pelvic rehab therapist started with a patient whispering to me in the middle of a busy sports/ortho clinic gym; “is it normal to leak when you laugh”. I was treating her after her total hip replacement and my first question was “where are you leaking”? I was concerned that her incision was leaking, that she had an infection and it was beyond me to understand why it would happen when she laughed! I was 24 years old and 2 years out of PT school. Little did I know, that one whispered question would lead me to where I am today. I am in my 25th year as a PT and 20th year specializing in pelvic rehabilitation.

When I started out there just were not many classes. I spent time learning from physicians, reading anything I could find and applying ‘general ‘orthopedic principles to the pelvis. I traveled to clinics and learned from other clinicians. I soaked up anything I could and brought it back to my clinical practice. When Holly Herman and Kathe Wallace asked me to teach with them I was humbled, honored and terribly nervous. Holly and Kathe where two of my greatest resources and to be able to teach along side them to help others along was humbling. As I prepared to teach I realized the breadth of what we do as pelvic rehab clinicians has grown exponentially since I started out.

Over the past 10 years of teaching the pelvic series with H&W; I noticed that for some of the participants there was a gap in confidence in palpation skills and in treatment techniques applied to the pelvic floor region. For most, it’s confidence in what they are feeling and where they are. This course came out of wanting to fill that gap. I wanted to allow a space that clinicians could come and spend two days learning, affirming and building confidence in their hands. They could then take those skills and confidence back to their clinics and help more patients.

The thought of writing this course was daunting. First off, written words are not my thing. Don’t get me wrong I love to read but me coming up with what to put on paper, much less a power point slide, frightened me. With much encouragement and support from colleagues and H&W, I got to work. The first thing was to think about what techniques to include. At some point after 20 years in the field, your hands just do the work and you don’t think about how you do something. My colleague and dear friend Katy Rice allowed me to sit down with her, practice a technique and then write down each specific step to do the skill. She would read them over and then attempt to do the technique by following only the written instructions. I also had patients who were instrumental in helping me choose what techniques to include. They would say to me “that is what made all the difference for me; it has to be included in what you teach others. “

I would think about who taught me each technique, whether it was a course, another clinician or a patient. I know that I did not make any of these up myself; while I may have modified a technique to work with my hands I did not originate them. Holly Tanner was so kind to brain storm with me and lead me to references for some of the techniques that we as clinicians use every day and that I was planning to include.

What happened next was months of me sitting at the kitchen table combing through books, articles, course manuals and online videos looking for origins of the techniques I use every day in my clinical practice. I wanted to be sure to give credit to sources. It was tedious but also inspiring to realize that some of these techniques have been around and documented since 1956 (Dicke, E., & Bischof-Seeberger, I.) and also that the same techniques are sited by multiple different sources. After about 6 months of our kitchen table not being suitable for dinner it was time to see what I had gathered and how it would all fit together. The result was this 2 day course: Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist which has seven labs including internal, external and combination techniques, home program/self care ideas and time for brainstorming treatment progressions. Join me in Philadelphia, PA this October 20 - 21 to learn these essential skills.

Recently, I had a patient present to my practice with unretractable vaginal pain that was causing her quite a bit of suffering. Peyton (name changed) had been referred by a local osteopathic physician. For around a year, she had increasing severe vaginal pain. There was no history of assault, trauma, fall, or injury around the time of onset of symptoms. However, she had a kidney infection that caused back pain in the month prior to her pain onset.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

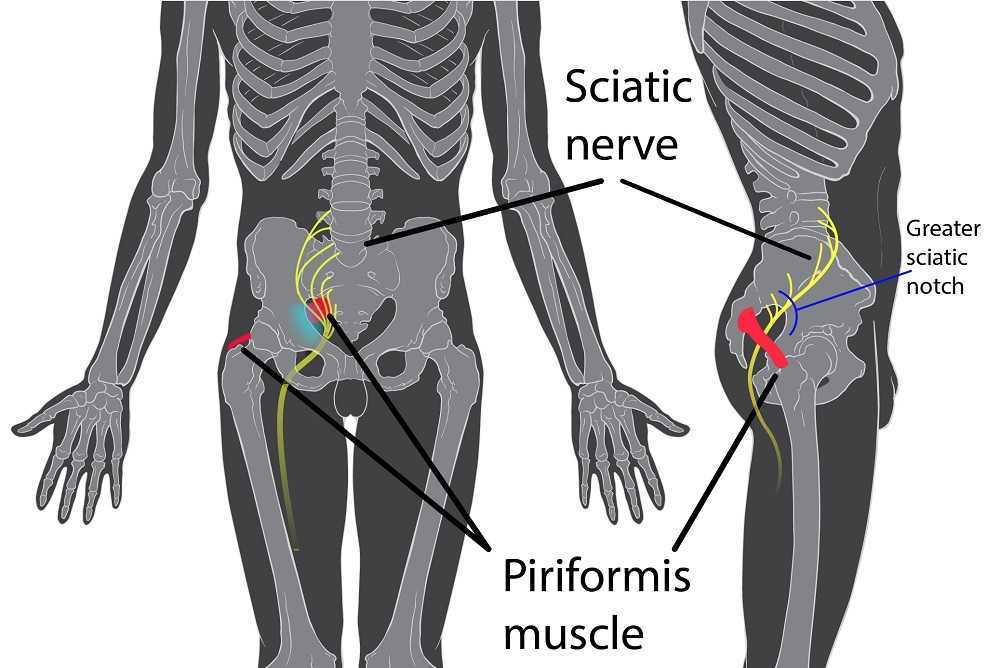

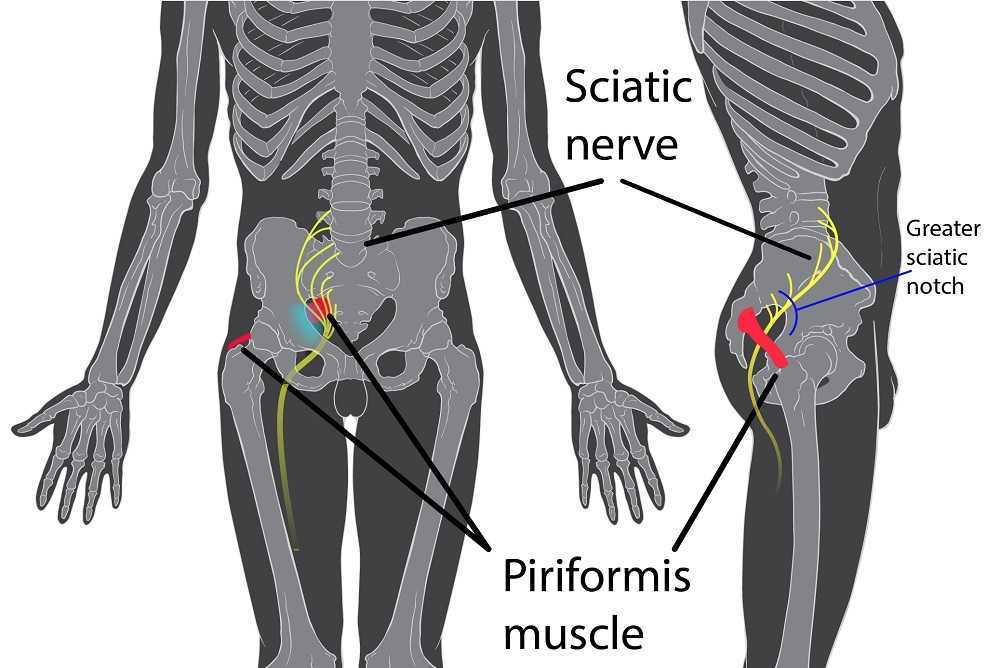

Objective findings revealed normal range of motion in her spine with the exception of limited forward flexion (feeling of back tightness at end range). Hip screening was negative for FABERS, labral screening or capsular pain patterns. General dural tension screening was positive for increased lower extremity and sensation of back tightness with slump c sit. Neural tension test was positive bilaterally for sciatic, R genitofemoral, L Iliohypogastric and Ilioinguinal nerves, and bilateral femoral nerves. Patient had a mild, barely perceptible lumbar scoliosis, and development of bilateral lower extremities and feet was symmetric and normal.

Because of the child’s age, we did not perform internal vaginal exam or treatment. This required treating the nerves that supply the vaginal area. All treatments were done with the patient’s mother present with both consent of the child and the mother.

For treatment, we started with the three inguinal nerves (Ilioinguinal, Iliohypogastric and genitofemoral) because of their relationship with the kidney (symptoms came on after kidney infection) as well as the correlation with the patient’s most limiting symptoms (genital pain). We cleared the fascia along the lumbar nerve roots, the lateral trunk fascia, the psoas, the inguinal region, the entrapments along the kidney and psoas, the inguinal rings and canal, and worked on neural rhythm (these techniques can be learned at the Pelvic Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment class that I will be teaching later this month).

Over the next weeks, we used similar treatments for the sciatic nerve, femoral nerve, pudendal, and coccygeal nerves. We noted that the patient had an area of restricted tissue along her coccyx that was adhered, and her symptoms had some correlation with tethered cord. We did lots of soft tissue work along the coccyx and working along the coccyx roots, including some internal rectal work. We also did fascial and visceral work in the bladder region, as well as in the lumbar and sacro-coccygeal region.

Peyton’s referring physician and mother were notified of findings and possible tethered cord symptoms (leg weakness and pain, bladder symptoms, delayed nocturnal continence). The patient’s family felt she was getting better and was not interested in any kind of surgical intervention, and her physician also felt that with our progress, he was not interested in exploring that referral, unless the family was interested.

After just 4 treatments Peyton was no longer having any vaginal symptoms and was emptying the bladder normally. After 8 treatments Peyton was reporting no more lumbar pain or lower extremity symptoms, and follow up treatments were reduced to once a month. The patient was given a home program of neural flossing in a small yoga program we recorded on her mother’s phone. We had her mother work on the small area that remained adhered along patient’s tailbone. The area is much smaller, but it reproduces some pelvic pain for the patient, so we are carefully and slowly working along this area because of some of the global neural sx it produces.

The patient’s mother reports she is more active, no longer complaining of leg or vaginal pain. The patient has less generalized anxiety and she is able to void fully. When the pt grows in height, there is a return in some symptoms, likely due to increased neural tension. So, we have the family on standby and when the patient grows, they come back in for 2 visits, which is usually enough to get the patient back to her new baseline.