![]()

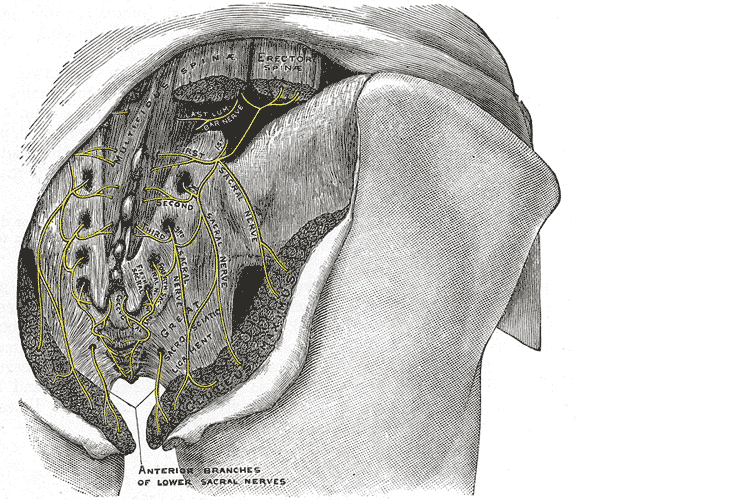

Central nervous system damage or disease can have a significant negative impact on pelvic organ and pelvic muscle function, adding to the functional burden that we may observe with movement, ADL, and communication/cognition deficits. The intricacies of central nervous system involvement in pelvic organ function can be traced back to our early years of development. Learning to walk and talk as a child happens before the ability to control our bladder and bowel emptying. This level of control requires a well-developed, intricately organized central and autonomic nervous system. It is understandable then, that even minor damage to our central nervous system and nerve pathways can compromise the intricacies of the complexly integrated pelvic viscera and pelvic floor dynamic.

Neurogenic bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction are generally defined as an impairment in these organs that results from neurologic damage or disease. The prevalence of neurogenic bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunction is somewhat uncertain due to limited studies in the neurologic population, however, typically the reports present a wide range. Neurogenic pelvic impairments can be highly variable and dependent on several factors including, but not limited to, lesion level, traumatic etiology (i.e., head, or spinal cord injury), non-traumatic etiology (i.e., stroke, Parkinson’s, Multiple Sclerosis), and comorbidities. The complexity of the person with a central nervous system pathology, whether it be damage or disease, can challenge even the most experienced clinician, and evaluating and treating these individuals can seem like a daunting and intimidating endeavor. Additionally, therapeutic intervention studies in the neurologic population are also less abundant, and individuals with neurologic deficits are often excluded.

Understanding your patient’s neurologic diagnosis, level of injury and corresponding probable neurological system impairments can help you decide on the best assessment and intervention strategy for your patient. Let’s first consider an upper motor neuron (UMN) lesion. This type of lesion can occur in the cortex and even down through the spinal cord descending motor tracts, which are located in the columns of the spinal cord. These individuals typically experience predominant bladder storage dysfunction or detrusor overactivity, increased muscle tone/spasticity in the pelvic floor, and reflexive bowel function. In contrast, a lower motor neuron (LMN) lesion can occur anywhere along the spinal cord within the LMN cell bodies in the anterior horns, along the pathway of a peripheral motor nerve, or at the motor neuromuscular junction. These individuals typically experience bladder storage or voiding symptoms, possible elevated post-void residuals if injury affects the sacral reflex arc, pelvic floor laxity or weakness, impaired descending and rectosigmoid transit, and areflexive bowel function.

In my course Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation scheduled for November 1-2, we will review basic neuroanatomy concepts. We will take a deep dive into the autonomic nervous system's control of the bladder, bowel, and sexual health organs. This will provide a general overview for considering the level of neurologic injury and the impairments you will likely observe. Parkinson disease will be our primary focus, however, my hope is that you can also begin to generalize this knowledge to other neurologic conditions that you treat in your clinic.

Resources:

- Fowler, C. J., Panicker, J. N., & Emmanuel, A. (Eds.). (2010). Pelvic organ dysfunction in neurological disease: clinical management and rehabilitation. Cambridge University Press.

- Lamberti, G., Giraudo, D., & Musco, S. (Eds.). (2019). Suprapontine Lesions and Neurogenic Pelvic Dysfunctions: Assessment, Treatment and Rehabilitation. Springer Nature.

AUTHOR BIO:

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC (she/her) graduated with her master’s degree in Occupational Therapy from Concordia University Wisconsin in 2002 and works for Aurora Health Care at Aurora Sinai Medical Center in downtown Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Erica specializes in female, male, and pediatric evaluation and treatment of the pelvic floor and related bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues. She is board-certified in Biofeedback for Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction (BCB-PMD) and is a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) through Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC (she/her) graduated with her master’s degree in Occupational Therapy from Concordia University Wisconsin in 2002 and works for Aurora Health Care at Aurora Sinai Medical Center in downtown Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Erica specializes in female, male, and pediatric evaluation and treatment of the pelvic floor and related bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues. She is board-certified in Biofeedback for Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction (BCB-PMD) and is a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) through Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Erica has attended extensive post-graduate rehabilitation education in the area of Parkinson disease and exercise. She is certified in LSVT (Lee Silverman) BIG and is a trained PWR! (Parkinson’s Wellness Recovery) provider, both focusing on intensive, amplitude, and neuroplasticity-based exercise programs for people with Parkinson disease. Erica is an LSVT Global faculty member. She instructs both the LSVT BIG training and certification course throughout the nation and online webinars. Erica partners with the Wisconsin Parkinson Association (WPA) as a support group, event presenter, and author in their publication, The Network. Erica has taken a special interest in the unique pelvic floor, bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues experienced by individuals diagnosed with Parkinson disease.

This week for the Pelvic Rehab Report, Holly Tanner sat down to interview faculty member Erica Vitek, MOT, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC on her specialty course Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation. If you would like to learn more about working with this patient population join Erica on June 24th-25th for the next course date!

This is Holly Tanner with the Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehab Institute and I'm here with Erica Vitek who's going to tell us about of course that she has created for Herman and Wallace. Erica, will you tell us a little bit about your background?

Yes. Absolutely. Thanks for chatting with me today about my course! So my course is Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation. I'm just so excited to be part of the team and to be sharing all this great information. How I got the idea for the course is that there was a need for more neuro-type topics related to pelvic health, and individuals were reaching out to me because my specialty is in both Parkinson disease, rehabilitation, as well as pelvic health, and I always talked about the connections and wanting to bring that information to more people. So I wanted to plate all that information together in this great course.

I got started specializing in Parkinson's back in the early 2000s. I was hired at a hospital as an occupational therapist working with people with Parkinson disease. But when I was in college my real interest was pelvic health. So I kind of got thrown into learning a whole lot about Parkinson disease at that time and I got really interested in how it all related to what I really wanted to do, which was pelvic health. I was able to connect that all, really right from the beginning of my career. Even though I started more on the physical rehabilitation side of Parkinson disease, which I continue to this day. I am able to combine those two passions of mine.

I also am an instructor with LSVT Global(1)and so we do LSVT BIG®(2) course training and certification workshops and I work with them a lot. I also have still a physical rehab background, as well as my connection to the public health background, and I bring that all together in my course Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation. We have two packed-full days of information and I think really it does translate well to the virtual environment.

What are the connections between neuro and pelvic health? Can you talk about what some of the big cornerstone pieces are that you get to dive into with your class?

The beginning of the course on the first day is going back to the basics of neuro in general. Really getting our neuro brains on and thinking about terminology, topics related to neurotransmitters and the autonomic nervous system. Individuals with Parkinson’s specifically, their motor system is affected but also their non-motor systems. This includes autonomic function, the limbic system, and all of the different motor functions that also affect the pelvic floor in addition to all of the other muscles in the body.

We have all of this interplay of things going on that affect the bladder, bowel, and sexual health systems in individuals with Parkinson's that is a little bit different than your general population. There are a multitude of bladder issues that are very specific to the PD population, for example, overactive bladder.

This is just one example of the depths we go into right in the beginning on day one where we get into the neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of why that is actually happening. This then helps us go into day two where we talk about the practicality of what you do in the clinic about the things that are happening neurologically which is causing all of these bladder, bowel, and sexual health issues.

What kind of tools do you give to people to help practitioners understand and implement a treatment program?

People with PD are on very complex medication regimens and many of them are elderly, so the medication complexity is much more challenging in this population. At the end of day one, the last lecture, we go through the pharmacology very specifically for people with Parkinson’s in order to have a base of understanding of how that is interplaying with the pelvic health conditions.

We set the baseline of getting that information from your patient off the bat, then discuss what you want to be looking for when you start off with that patient and the importance of finding out what kind of bladder and bowel medications they have taken thus far and how that can potentially interplay with their Parkinson’s. Individuals with PD can have potentially worse side effects from some of those medications that are used for bladder issues specifically. We dig into what to look for, we talk a lot about practical behavioral modifications using bladder and bowel diaries and things like that to weed out some things in addition to using our other skills as pelvic health practitioners.

How can people prepare themselves to come to Parkinson Disease and Pelvic Rehabilitation, are there required readings or things that would be helpful for people to catch up a little bit on the pelvic health or neuro side?

I feel like, and I hope, that I did a really good job at the basic review right at the beginning so we can talk through these topics together. I prefer to take a course and not have to spend a lot of extra time on the pre-recordings because sometimes that can be overwhelming with busy lifestyles. When I put together this course I really wanted us to focus together as a group as we start the class to dig into those basics at the beginning and not have a lot of required things to do prior.

So what I did at the beginning of the course is to make a lot of tables, a lot of charts, and a lot of drawings, that we can reference (we don’t have to memorize it) and look at as needed. We can look at a chart and a drawing right next to it in the manual. I spent a lot of time just putting it all down in words, what I’m saying, so you don’t have to take a lot of notes. I think this has really helped practitioners as we get into the course and learn about the details of Parkinson’s and pelvic health.

What is it that makes you so passionate about working with these patients and continuing to learn and share your knowledge?

It is so heartwarming and feels so good to help these individuals. The motor symptoms of PD are really the ones recognized by physicians or even outwardly noticed even by other individuals. These private conditions of pelvic health that we are helping with are things that they might not even mention to their physician. Maybe we find out when we are doing other physical rehab or when colleagues refer them to us because they know what we do, and to help them with something of this magnitude that affects their everyday life - when they have trouble just walking, or moving or transferring.

Their caregiver burden for these individuals is so high because their loved one - now turned caregiver - is helping them do everything. We can make such an impact on these individuals. I mean, we do on other people too, but when you have a progressive neurologic condition and we can make an effect on shaping techniques they can use to improve their day-to-day. It’s just so great to be able to help them.

Sometimes these patients with PD can have cognitive impairments, they can have difficulties learning, and that can be helpful for the care partner. It can be a significant reduction in their burdon. I do talk a lot in the course about cognitive impairment and I give a lot of tips about how we can train and some ideas. People with Parkinson’s muscles and minds are a little different so there are some great tips that I can provide and lots of clinical experience.

I’ve been an occupational therapist for over 20 years, so I have a ton of clinical experience with this population. It’s been the population I’ve worked with my entire career. I hope I can provide the passion that I have for working with these individuals as well as the individuals who take my class.

I’m sure you would agree that we need more folks knowledgeable about Parkinson’s and combine that with pelvic health knowledge as well.

There are over a million people in the United States alone that have Parkinson disease. It’s the second most common neuro-degenerative disorder just behind Alzheimer’s disease. So there are so many individuals dealing with this and I think we can really expand our practices. I don’t think a lot of individuals that work in pelvic health market themselves to neurologists. There is an opening there for additional referrals and more people that we can help.

References:

- SVT Global is an organization that develops innovative treatments that improve the speech and movement of people with Parkinson’s disease and other neurological conditions. They train speech, physical and occupational therapists around the world in these treatments so that they can positively impact the lives of their patients.

- LSVT BIG®: Physical Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease and Similar Conditions. LSVT BIG trains people with Parkinson disease to use their body more normally.

Dustienne Miller, CYT, PT, MS, WCS instructed the H&W remote course Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Dustienne passionately believes in the integration of physical therapy and yoga in a holistic model of care, helping individuals navigate through pelvic pain and incontinence to live a healthy and pain-free life. You can find Dustienne Miller on Instagram at @yourpaceyoga

Research demonstrates multiple benefits of a yoga practice that extend beyond the musculoskeletal system. These benefits include improved mood and depression, changes in pain perception, improved mindfulness and associated improved pain tolerance, and the ability to observe situations with emotional detachment.

Do the brains of yoga practitioners vs non-practitioners look different?

A study by Villemure et al looked at the role the insular cortex plays in mediating pain in the brains of yoga practitioners. They included various styles of yoga to capture the essence of yoga across multiple styles - Vinyasa, Ashtanga, Kripalu, Sivananda, and Iyengar.

Rewind back to neuroanatomy class - remember the insular cortex? The insular cortex is responsible for sensory processing, decision-making, and motor control by communicating between the cortical and subcortical aspects of the brain. The outside inputs include auditory, somatosensory, olfactory, gustatory, and visual. The internal inputs are interoceptive (Gogolla).

Villemure et al found several interesting objective differences. The practitioners had increased grey matter volume in several areas of the brain. This increase in grey matter specifically in the insula correlated with increased pain tolerance. The length of time practiced correlated with increased grey matter volume of the left insular cortex. Additionally, white matter in the left intrainsular region demonstrated more connectivity in the yoga group.

Other differences were seen in strategies utilized to manage pain. Most folks in the yoga group expected their practice would decrease reactivity to pain, which it did. The yoga group used parasympathetic nervous system accessing strategies and interoceptive awareness. These strategies were breathwork, noticing and being with the sensation, encouraging the mind and body to relax, and acceptance of the pain. The control group strategies were distraction techniques and ignoring the pain.

The authors determine that the insula-related interoceptive awareness strategies of the yoga practitioners being used during the experiment correlated with the greater intra-insular connectivity. Therefore, the authors conclude that the insular cortex can act as a pain mediator for yoga practitioners.

The more strategies our patients have for pain management, the better! Yoga is one of several non-invasive modalities our patients can add to their healing toolbox.

Yoga for Pelvic Pain was developed by Dustienne Miller to offer participants an evidence-based perspective on the value of yoga for patients with chronic pelvic pain. This course focuses on two of the eight limbs of Patanjali’s eightfold path: pranayama (breathing) and asana (postures) and how they can be applied for patients who have hip, back, and pelvic pain.

A variety of pelvic conditions are discussed including interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, vulvar pain, coccydynia, hip pain, and pudendal neuralgia. Other lectures discuss the role of yoga within the medical model, contraindicated postures, and how to incorporate yoga home programs as therapeutic exercise and neuromuscular re-education both between visits and after discharge.

References:

Gogolla N. The insular cortex. Current Biology. 2017; 27(12): R580-R586.

Villemure C, Ceko M, Cotton VA, Bushnell MC. Insular cortex mediates increased pain tolerance in yoga practitioners. Cereb Cortex. 2014 Oct;24(10):2732-40. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht124. Epub 2013 May 21. PMID: 23696275; PMCID: PMC4153807.

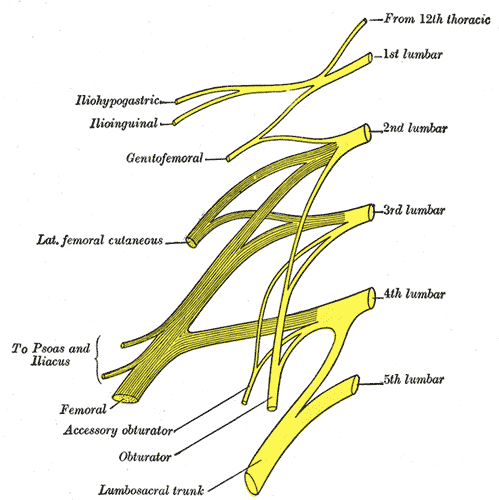

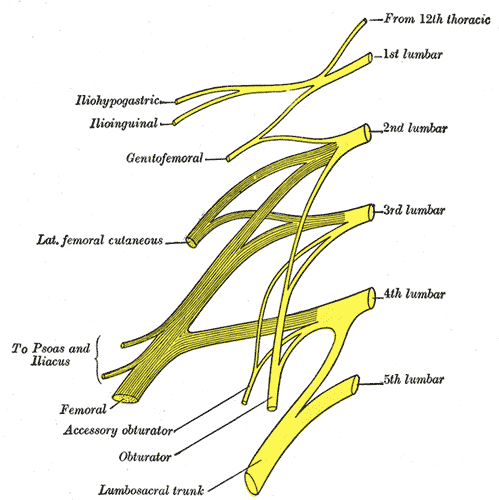

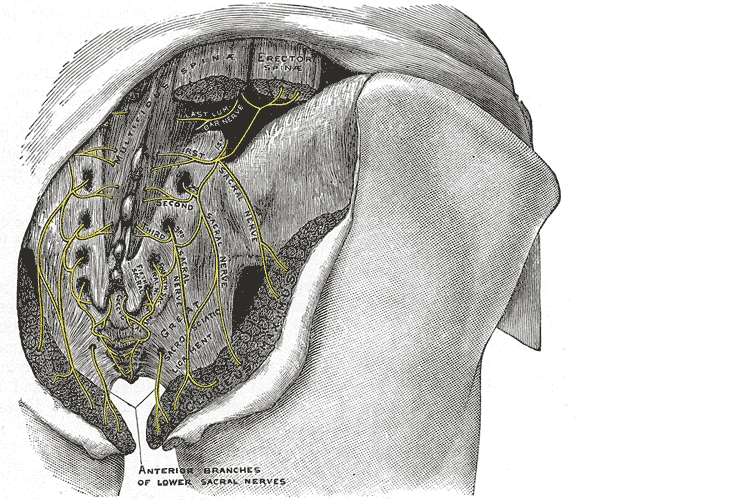

The lumbar sacral nerve plexus can be divided into the direction the nerves travel, either anterior or posterior. This post will focus on anterior hip nerves. I remember writing about the brachial plexus over and over in physical therapy school, but only a few times for the lumbosacral plexus. Patients frequently report anterior hip and pubic pain and can often have signs and symptoms of nerve entrapment. This article orients the reader to links between signs and symptoms and examination to help appropriately diagnosis specific nerves in the athletic population.

The obturator, femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous are more commonly entrapped in sports injuries. Although the three nerves that travel together through the inguinal canal (ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral) are less common, however surgery can create nerve entrapment sequelae.

The obturator, femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous are more commonly entrapped in sports injuries. Although the three nerves that travel together through the inguinal canal (ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genitofemoral) are less common, however surgery can create nerve entrapment sequelae.

There are a few places where the obturator nerve can become squished. Typically, as it leaves the obturator canal which presents at medial thigh pain, and then again in the fascia of the adductors which presents as pain with abduction. The challenge is to differentiate between the nerve and adductor strain. Obturator nerve entrapment will test positive with passive hip abduction and extension, but negative resisted hip adduction.

The femoral nerve can become entrapped in a kind of compartment syndrome as it goes between the psoas and iliacus. This can lead to compression to the neurovascular bundle with resultant swelling, edema, and ischemia. Signs of femoral nerve compression include anterior thigh numbness and paresthesias. Occasionally, this can also include the saphenous nerve with symptoms continuing along medial knee to foot. Femoral nerve entrapment can create quadricep muscle weakness and atrophy, with diminished or absent patella tendon reflexes. Symptoms are reproduced with hip extension and knee flexion thereby elongating the femoral nerve.

The lateral femoral cutaneous (LFC) nerve is sensory. Diagnosed as meralgia paresthetica, the LFC nerve is typically entrapped where it penetrates under the inguinal ligament just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). Symptoms include numbness, tingling, hypersensitivity to touch, burning along outer thigh along the iliotibial band. The LFC nerve can often be compressed by wearing heavy belts (scuba divers, construction belts, etc). Special tests that indicate LFC are pelvic compression in side lying with involved side up to slack the inguinal ligament and Tinels sign.

Anterior hip pain is fairly common in pelvic floor patients. Differential diagnosis and treatment of these anterior nerves can allow patients to return to full daily function. To learn manual assessment and treatment techhniques for the lumbar nerves, consider attending Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment.

Martin R, Martin HD, Kivlan BR. Nerve Entrapment In The Hip Region: Current Concepts Review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Dec;12(7):1163-1173.

The female sexual response cycle is more than physical stimulation. As pelvic therapists, we frequently find ourselves treating pelvic pain that has interrupted a woman’s ability to enjoy her sexuality and sensuality. As physical therapists, we focus on the physical limitations and pain generators as a way of helping patients overcome their functional limitations. However, many of us find that once many of the physical symptoms have cleared with pelvic floor and fascial stretching, our patients are still apprehensive to engage physically, or they are not able to derive pleasure. There is clearly a gap that needs to be bridged that goes beyond pain.

Last year I taught my class, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment. I was honored and astounded to have Dee Hartmann, PT in my class. For those of you who do not know Dee, she has been a champion of our field for a long time, and she has been instrumental in elevating physical therapy as a first line of treatment in pelvic pain through her work, international leadership, and representation in multiple organizations, including APTA SOWH, ISSVD, IPPS, NVA, ISSWSH, and as an editor for the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Last year I taught my class, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment. I was honored and astounded to have Dee Hartmann, PT in my class. For those of you who do not know Dee, she has been a champion of our field for a long time, and she has been instrumental in elevating physical therapy as a first line of treatment in pelvic pain through her work, international leadership, and representation in multiple organizations, including APTA SOWH, ISSVD, IPPS, NVA, ISSWSH, and as an editor for the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

In this manual nerve class, I was teaching how to treat the path of the genitofemoral nerve, which affects the peri-clitoral tissues and sensation. We also covered manual therapy approaches to decrease restriction in the clitoral complex and improve the blood flow response in this region. Dee was fascinated and looped me into what she had been working on for the past several years. She has been working as part of a company called Vulvalove with her partner, sex therapist, Elizabeth Wood on studying and teaching women how to recapture their sensuality. Immediately, we wanted to combine forces in some way to present a way to approach these issues. So, when Dee invited me to present with Elizabeth and her at the Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association (CSM) this year, I was humbled and excited to jump on board.

With improved tissue mobility in the clitoral and vaginal area, blood flow is able to improve through any previously restricted tissues. With any manual therapy or soft tissue work, it is expected that cutaneous circulation of blood and lymph will alter. In studies, a measure of this blood flow, VPA (Vaginal Pulse Amplitude) is higher in the arousal than the non-arousal state in women.4 “The first measurable sign of sexual arousal is an increase in the blood flow. This creates the engorged condition, elevates the luminal oxygen tension and stimulates the production of surface vaginal fluid by increased plasma”.5 Manual therapy can likely affect this.1,2. During our CSM talk, I will discuss the neurovascular anatomy and will have a brief video of manual techniques to enhance these pathways in my portion of the presentation.

In the 19th century, female orgasm and sensuality was believed to be more vaginal, but as the 20th century unfolded, understanding of the clitoral tissues improved. More recent research reveals the origin of female pleasure is more complex, involving the clitoris, vulva, vagina, and uterus.3 However, female response is more complicated than just anatomy below the waist.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is a measure of autonomic nervous system health and the ability to flux between sympathetic and parasympathetic states. Autogenic training and meditation or mindfulness have been shown in multiple studies to improve HRV. A study by Stanton in 2017 demonstrated that even one session of autogenic training can increase HRV and VPA (Vaginal Pulse Amplitude, a measure of arousal). In our talk at CSM, Dee will cover the role of autogenics and how to specifically and practically use our autonomic state to influence our perception and feeling of pleasure. Dee will also cover extensive clitoral anatomy to have a better understanding of how this intricate complex functions and is structured in women.

Elizabeth Wood, a former sex therapist who is now a sex educator, will then present on the arousal cycle and what can be done physiologically to prepare the arousal network for climax. Elizabeth will help us to better define and understand the roles of arousal, calibration, and exploring sensuality, including exercises to help a patient have a more fulfilling experience once the physical pain is resolved. As Elizabeth says, “Knowledge is an antidote to shame and an invitation to pleasure”.

If you will be at CSM, please come join us at the opening session, Thursday February 13 from 8am-10am (PH2540), “Now That The Pain Is Gone, Where’s the Pleasure”.

If you can’t make it to CSM, I hope to see you at one of my nerve classes, “Lumbar Nerve Manual Therapy and Assessment” this year in Madison, WI April 24-26 or Seattle, WA October 16-18 to further explore manual therapies to improve sensation and neural feedback loops and to continue this conversation!

1. Portillo-Soto, A., Eberman, L. E., Demchak, T. J., & Peebles, C. (2014). Comparison of blood flow changes with soft tissue mobilization and massage therapy. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20(12), 932-936.

2. Ramos-González, E., Moreno-Lorenzo, C., Matarán-Peñarrocha, G. A., Guisado-Barrilao, R., Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M. E., & Castro-Sánchez, A. M. (2012). Comparative study on the effectiveness of myofascial release manual therapy and physical therapy for venous insufficiency in postmenopausal women. Complementary therapies in medicine, 20(5), 291-298.

3. Colson, M. H. (2010). Female orgasm: Myths, facts and controversies. Sexologies, 19(1), 8-14.

4. Rogers, G. S., Van de Castle, R. L., Evans, W. S., & Critelli, J. W. (1985). Vaginal pulse amplitude response patterns during erotic conditions and sleep. Archives of sexual behavior, 14(4), 327-342.

5. Stanton, A., & Meston, C. (2017). A single session of autogenic training increases acute subjective and physiological sexual arousal in sexually functional women. Journal of sex & marital therapy, 43(7), 601-617.

Pain demands an answer. Treating persistent pain is a challenge for everyone; providers and patients. Pain neuroscience has changed drastically since I was in physical therapy school. This update comes from the International Spine and Pain Institute headed by the lead author Adriaan Louw, PT, PhD. If you are interested in reading more about persistent pain, I suggest reading the article in its entirety.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

Pain neuroscience education is a way to explain pain to patients, often with analogies, with a focus on neurobiology and neurophysiology as it relates to that individuals pain experience. To be able to educate our patients, we as providers, must be able to understand neuromatrix, output, and threat. Moseley states “[p]ain is a multiple system output activated by an individual’s specific pain neuromatrix. The neuromatrix is activated whenever the brain perceives a threat”. If that sounds like gibberish, consider watching this TEDx talk by Lorimer Moseley on YouTube (the snake bite story is a favorite of mine):

What is a neuromatrix? Essentially, it is a pain map in the brain; a network of neurons spread throughout the brain, none of which deal specifically with pain processing. The way I visualize it is to think about what goes on when you think of your grandmother. There isn’t a grandmother center in the brain, but there are sights and smells (sensory), feelings (emotional awareness), and memories that all come up when you think about her. When we are overwhelmed with pain, those regions become taxed and the individual may have difficulty concentrating, sleeping, and/or may lose his/her temper more easily. Just as each person’s grandmother is different so is a person’s pain and the neuromatrix is affected by past experiences and beliefs.

Pain is an output. It is a response to a threat. When a person is exposed to a threatening situation, biological systems like the sympathetic nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, gastrointestinal system, and motor response system are activated. When a stress response occurs, these systems are either heightened or suppressed to help cope, thanks to the chemicals epinephrine and cortisol.

What is a threat? Threats can take a variety of forms; accidents, falls, diseases, surgeries, emotional trauma, etc. Tissues are influenced by how the individual thinks and feels, in addition to social and environmental factors. The authors propose that when individuals live with chronic pain, their body reacts as though they are under a constant threat. With this constant threat the system reacts and continues to react, and the nervous system is not allowed to return to baseline levels. This can create a patient presentation with immunodeficiency, GI sensitivity, poor motor control, and more. This sounds like most patients who walk into my clinic. The authors suggest that one system may be affected more and that can influence what the patient is diagnosed with even though the underlying biology is the same for many conditions. There are theories for why that happens; genetics, biological memory, or it could be the lens of the provider that the patient sees. There is a table in the article that shows symptoms, diagnosis, and current best evidence treatment for the conditions of fybromyalgia, chronic fatique syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease which is worth a look. The treatments all work to calm the central nervous system.

The authors go on to question the relationship between thyroid function and these conditions as changes in cortisol and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is fascinating, and confusing. Luckily, the Pelvic Floor Series Capstone course does a great job breaking it down.

Now that this hypothetical patient is in our treatment room what do we do? The authors suggest seeing these conditions for what they are: chronic pain conditions. They recommend that physical therapists see past the label that a patient may have picked up with a previous diagnosis, and keep the following in mind when treating these patients:

- They are hurting

- They are tired

- They may have lost hope

- They may be disillusioned by the medical community

- They need help

These people need the following from their medical providers:

- Compassion

- Dignity

- Respect

With empathy and understanding therapists can use skills in education, exercise and movement with the intent to improve system function (immune, neural, and endocrine), rather than fixing isolated mechanical deficits.

Louw, Adriaan PT, PhD; Schmidt, Stephen PT ; Zimney, Kory PT, DPT ; Puentedura, Emilio J. PT, DPT, PhD Treat the Patient, Not the Label: A Pain Neuroscience Update.[Editorial] Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 43(2):89-97, April/June 2019.

“My butt hurts.” This is such a common subjective complaint in my practice as a manual therapist, and many patients insist it must be a muscle problem or jump to the conclusion it must be “sciatica.” I often tell patients if they did not get shot or bit directly in the buttocks, the pain is most likely referred from nerves that originate in the spine. Although blunt trauma to the buttocks can certainly be the culprit for pain in the gluteal region, a basic understanding of the neural contribution is essential for providing appropriate treatment and a sensible explanation for patients.

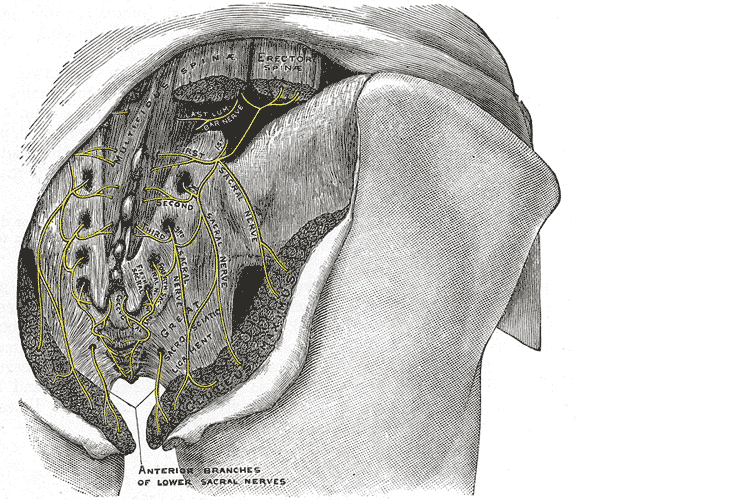

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

Iwananga et al., (2018) presents a very recent article regarding the innervation of the piriformis muscle, which has been suspected to be the superior gluteal nerve, by dissecting each side from ten cadavers. Often the piriformis muscle can be compromised through total hip replacements with a posterior approach, hip injuries, or chronic pain disorders. This particular study verifies there is no singular nerve that innervates the piriformis muscle, and the most common innervation sources are the superior gluteal nerve (70% of the time) and the ventral rami of S1 (85% of the time) and S2 (70% of the time). The inferior gluteal nerve and the L5 ventral ramus were each found to be part of the innervation only 5% of the time.

Wang et al., (2018) focused on what causes gluteal pain with lumbar disc herniation, particularly at L4-5, L5-S1. They emphasize the important factor that dorsal nerve roots have sensory fibers and ventral roots contain motor neurons, and spinal nerves are mixed nerves, since they have ventral and dorsal roots. They discuss other contributing nerves, but continuing our focus on the superior gluteal nerve, it stems from L4-S1 ventral rami and not only allows movement of gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and gluteus maximus, it also provides sensation to the area. This nerve can certainly produce pain in the gluteal region when irritated. In lumbar disc herniation of L4-5 or L5-S1, the ventral rami of L5 or S1 can be comprised or irritated at the level of the nerve root and provoke gluteal pain because they mediate sensation in that area.

Once the superior gluteal nerve (or any sacral nerve) is implicated as the root of pain, should we just shrug our shoulders and send them to pain management? I strongly suggest we learn how to address the issue in therapy using our hands with manual techniques and appropriate exercises. The Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment course should be a priority on your bucket list of continuing education to help alleviate any further pain in the butt.

Lung K, Lui F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Superior Gluteal Nerve. [Updated 2018 Dec 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535408/

Iwanaga J, Eid S, Simonds E, Schumacher M, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. (2018). The Majority of Piriformis Muscles are Innervated by the Superior Gluteal Nerve. Clinical Anatomy. doi: 10.1002/ca.23311. [Epub ahead of print]

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Yan, Y., Zhang, L., Guo, C., Peng, Z., & Kong, Q. (2018). Possible pathogenic mechanism of gluteal pain in lumbar disc hernia. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 19(1), 214. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-2147-y

Does cognitive self-regulation influence the pain experience by modulating representations of nociceptive stimuli in the brain or does it regulate reported pain via neural pathways distinct from the one that mediates nociceptive processing? Woo and colleagues devised an experiment to answer this question.1 They invited thirty-three healthy participants to undergo fMRI while receiving thermal stimulation trial runs that involved 6 levels of temperatures. Trial runs included “passive experience” where participants passively received and rated heat stimuli, and “regulation” runs, where participants were asked to cognitively increase or decrease pain intensity.

Instructions for increasing pain intensity included statements such as “Try to focus on how unpleasant the pain is. Pay attention to the burning, stinging and shooting sensation.” Instructions for decreasing pain intensity included statements such as “Focus on the part of the sensation that is pleasantly warm. Imagine your skin is very cool and how good the stimulation feels as it warms you up.” The effects of both manipulations on two brain systems previously identified in the literature were examined. One brain system was the “neurological pain signature” (NPS), a distributed pattern of fMRI activity shown to specifically track pain intensity induced by noxious inputs. The second system was the pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) with the nucleus accumbens (NAc), shown to play a role in both reappraisal and modulation of pain. In humans, the vmPFC tracks spontaneous pain when it has become chronic and potentially dissociated from nociception.2,3 In patients with sub-acute back pain, the vmPFC-NAc connectivity has been shown to predict subsequent transition to chronic back pain.4 In addition, the vmPCF is hypothesized to play a role in the construction of self-representations, assigning personal value to self-related contents and, ultimately, influencing choices and decisions.5

Instructions for increasing pain intensity included statements such as “Try to focus on how unpleasant the pain is. Pay attention to the burning, stinging and shooting sensation.” Instructions for decreasing pain intensity included statements such as “Focus on the part of the sensation that is pleasantly warm. Imagine your skin is very cool and how good the stimulation feels as it warms you up.” The effects of both manipulations on two brain systems previously identified in the literature were examined. One brain system was the “neurological pain signature” (NPS), a distributed pattern of fMRI activity shown to specifically track pain intensity induced by noxious inputs. The second system was the pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) with the nucleus accumbens (NAc), shown to play a role in both reappraisal and modulation of pain. In humans, the vmPFC tracks spontaneous pain when it has become chronic and potentially dissociated from nociception.2,3 In patients with sub-acute back pain, the vmPFC-NAc connectivity has been shown to predict subsequent transition to chronic back pain.4 In addition, the vmPCF is hypothesized to play a role in the construction of self-representations, assigning personal value to self-related contents and, ultimately, influencing choices and decisions.5

Woo and colleagues found that both heat intensity and self-regulation strongly influenced reported pain, however they did so by two differing pathways. The NPS mediated only the effects of nociceptive input. The self-regulation effects on pain were mediated by the NAc-vmPFC pathway, which was unresponsive to the intensity of nociceptive input. The NAc-vmPFC pathway responded to both “increase” and “decrease” self-regulation conditions. Based on these results, study authors suggest that pain is influenced by both noxious input and cognitive self-regulation, however they are modulated by two distinct brain mechanisms. While the NPS encodes brain activity closely tied to primary nociceptive processing, the NAc-vmPFC pathway encodes information about evaluative aspects of pain in context. This research is limited in that the distinction between pain intensity and pain unpleasantness was not included and the subjects were otherwise healthy. Further research is warranted on the effects of this cognitive self-regulation model on brain pathways in patients with chronic pain conditions.

Even with the noted limitations, this research invites the clinician to consider the role of both nociceptive mechanisms and cognitive self-regulatory influences on a patient’s pain experience and suggests treatment choices should take both factors into consideration. Mindful awareness training is a treatment that contributes to cognitive self-regulatory brain mechanisms.6 When mindful, pain is observed as and labeled a sensation. The term “sensation” carries a neutral valence compared to “pain” which may reflect greater alarm or threat to an individual. The mind is recognized to have a camera lens-like quality that can shift from zoom to wide angle. While pain can draw attention in a more narrow focus on the painful body area, when mindful, an individual can deliberately adopt a wide angle view, focusing on pain free areas and other neutral or positive states. In addition, when mindful, the unpleasant sensation rests in awareness not characterized by fear and distress, but by stability, compassion and curiosity. Patients may not have control over the onset of pain, but with mindfulness training, they can take control over their response to the pain. This deliberate adoption of mindful principles and practices can contribute to cognitive self-regulatory brain mechanisms that can ultimately impact pain perception.

I am excited to share additional research and practical clinical strategies that help patients self-regulate their reactions to pain and other symptoms in my 2019 courses, Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals at University Hospitals in Cleveland OH, April 6 and 7 and Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment in Houston TX, October 26 and 27 and Portland OR May 18 and 19. Hope to see you there!

1. Woo CW, Roy M, Buhle JT, Wager TD. Distinct brain systems mediate the effects of nociceptive input and self-regulation on pain. PLoS;2015;13(1):e1002036.

2. Baliki MN, Chialvo DR, Geha PY, Levy RM, et al. Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of chronic back pain.J Neurosci. 2006;26(47):12165-73.

3. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(pt9):2751-68.

4. Baliki MN, Peter B B, Torbey S, Herman KM, et al. Corticostriatal functional connectivity predicts transition to chronic back pain. Nat Neurosci.2012;15(8):1117-9.

5. D’Argembeau. On the role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in self-processing: The Valuation Hypothesis. Front Human Neurosci. 2013;7:372.

6. Zeidan F, Vago DR. Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: a mechanistic account. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016 Jun;1373(1):114-27.

Most people are told that inguinal hernia repair is a low risk surgery. While death or severe injury is rare, penile or testes pain after hernia repair is not a novel or recent finding. In 1943, Magee first discussed patients having genitofemoral neuralgia after appendix surgery. By 1945, both Magee and Lyons stated that surgical neurolysis gave relief of genital pain following surgical injury (neurolysis is a surgical cutting of the nerve to stop all function). However, it should be noted that with neurolysis, sensory loss will also occur, which is an undesired symptom for sexual function and pleasure. In 1978 Sunderland stated genitofemoral neuralgia was a well-documented chronic condition after inguinal hernia repair.

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

Let’s do a quick anatomy review. The inguinal canal is located at the lower abdomen and is actually an extension of the external oblique muscles. Is travels along the line from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle, occupying grossly the medial third of this segment. It has a lateral ring where contents from the abdomen exit and a medial ring where the contents of the canal exit superficially. This ring contains the spermatic cord (male), round ligament (female), as well as the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves. For males, in early life, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity to the exterior scrotal sac through the inguinal canal, bringing a layer of the obliques, transverse abdominus, and transversalis fascia with them within the first year of life. Just as a female can experience prolapse from prolonged increased intra-abdominal pressure, a male can have a herniation through the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal with increased abdominal pressure. Such pressure inducing activities can be lifting, coughing, and sports activities. When this occurs, an inguinal hernia repair is generally indicated. Because the genitofemoral nerve is within the contents of the inguinal canal, it can be susceptible to surgery in this area. The genitofemoral nerve has sensory innervation to the penis and testes and is responsible for the cremasteric reflex. Symptoms of genitofemoral neuralgia in men can be penis or testes pain, numbness, hypersensitivity, and decreased sexual satisfaction or function.

In 1999 Stark et al noted pain reports as high as 63% post hernia repair. The highest rates of genitofemoral neuralgia are reported with laparoscopic or open hernia repair (Pencina, 2001). The mechanism for GF neural entrapment is entrapment within scar or fibrous adhesions and parasthesia along the genitofemoral nerve (Harms 1984, Starling and Harms 1989, Murovic 2005, and Ducic 2008). It is well known that scar and adhesion densify and visceral adhesions increase for years after surgery. Thus, symptoms can increase long after the surgery or may take years to develop. In 2006, Brara postulated that mesh in the region can contribute to subsequent genitofemoral nerve tethering which can be exacerbated by mesh in the inguinal or the retroperitoneal space. With an anterior mesh placement, there is no fascial protection left for the genitofemoral nerve.

Genitofemoral neuralgia is predominately reported as a result of iatrogenic nerve damage during surgery or trauma to the inguinal and femoral regions (Murovic et al, 2005). However, genitofemoral neuropathy can be difficulty and elusive to diagnose due to overlap with other inguinal nerves (Harms, 1984 and Chen 2011).

In my clinical experience, I have seen such symptoms after hernia repair, but also after procedures near the inguinal region such as femoral catheters for heart procedures, appendectomies, and occasionally after vasectomy.

As a pelvic PT, what are we to do with this information? First off, we can realize that all pelvic neuropathy is not necessarily due to the pudendal nerve. In the anterior pelvis, there is dual innervation from the inguinal nerves off the lumbar plexus as well as the dorsal branch of the pudendal nerve. When patients have a history of inguinal hernia repair, we can consider the genitofemoral nerve as a source of pain. Medicinally, the only research validated options for treatment are meds such as Lyrica or Gabapentin that come with drowsiness, dizziness and a score of side effects. Surgically neurectomy or neural ablation are options with numbness resulting, however, many patients do not want repeated surgery or numbness of the genitals. As pelvic therapists, we can manually fascially clear the path of the nerve from L1/L2, through the psoas, into and out of the canal and into the genitals. We can also manually directly mobilize the nerve at key points of contact as well as doing pain free sliders and gliders and then give the patient a home program to maintain mobility. Pelvic manual therapy can offer a low risk, side-effect free option to ameliorate the sequella of inguinal hernia repair. Come join us at Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment in Chicago this Spring to learn how to effectively treat all the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Cesmebasi, A., Yadav, A., Gielecki, J., Tubbs, R. S., & Loukas, M. (2015). Genitofemoral neuralgia: a review. Clinical Anatomy, 28(1), 128-135.

Lyon, E. K. (1945). Genitofemoral causalgia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 53(3), 213.

Magee, R. K. (1943). Genitofemoral Causalgia: New Syndrome. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 98(3), 311.

Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1978

Faculty member Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC recently created a two-course series on the manual assessment and treatment of nerves. The two courses, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment and Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment, are a comprehensive look at the nervous system and the various nerve dysfunctions that can impact pelvic health. The Pelvic Rehab Report caught up with Nari to discuss these new courses and how they will benefit pelvic rehab practitioners.

What is "new" in our understanding of nerves? Are there any recent exciting studies that will be incorporated into this course?

The course is loaded with a potpourri of research regarding nerves and histological and morphological studies. There are some fascinating correlations we see with nerve restrictions, wherever they are in the body. Frequently the nerves are compressed in fascial tunnels or areas of muscular overlap, then the nerve, wherever the location, frequently has local vascular axonal change, which increases the diameter of the nerve and prohibits gliding without pain. This causes local guarding and protective mechanisms. Changing pressure on the nerve can change that axonal swelling and allow gliding without pain.

New pain theory also supports that much of pain perception is the body perceiving danger or injury to a nerve. By clearing up the path of the nerve and mobilizing it, we can decrease the body's perception of nerve entrapment and thus create change in pain levels.

What do you hope practitioners will get out of this series that they can't find anywhere else?

I hope they will leave the course able to treat the nerves of the region, which is essentially the transmission pathway for most pelvic pain. I don't know of other courses that have this emphasis.

You've recently split your nerve course in two. Why the split?

I didn't want this class to be a bunch of nerve theory without the manual intervention to make change. After running the labs in local study groups, we found it took more time for people's hands to learn the language, art, and techniques of nerve work. To truly do the work justice and for participants to have a firm grasp of the manual techniques without being rushed, we found it takes time, and I wanted to honor that, as well as treating enough of the related factors and anatomy to make real and lasting change for patients.

How did you decide to divide up content?

Basically, we divided them up by anatomical origin:

The lumbar course covers the nerves of the lumbar plexus, the abdominal wall when treating diastasis, and treatment of the inguinal canal (obturator nerve, femoral nerve, iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral nerves). Also, the lumbar nerves have more effect in the anterior hip, anterior pelvis, and abdominal wall.

The sacral nerve course covers all the nerves of the sacral plexus (pudendal, sciatic, gluteal/cluneal, posterior femoral cutaneous, sciatic, and coccygeal nerves), as well as subtle issues in the sacral base and subtle coccyx derangement work as well as the relationship with the uterus and sacrum, to take pressure off the sacral plexus. The sacral nerves have more effect in the posterior and inferior pelvis and into the posterior leg and gluteals.

What are the main stories that either course tells?

Both courses tell the story of getting closer to the root of the pain to make more change in less time. Muscles generally just respond to the message the nerve is sending. Yet, by treating the nerve compression directly, we are getting much closer to the root of the issue and have more lasting results by changing the source of abnormal muscle tone. Rather than an intellectual exercise of discourse on nerves, we devote ourselves to the art of manual therapy to change the restrictions on the pathway of the nerve and in the nerve itself.

If someone went to the old nerve course, what's the next best step for them?

The first course was initially all the lumbar nerves with a dip into the pudendal nerve. They would want to take the sacral nerve course, as those nerves were not covered in the first round.

Anything else you would like to share about these courses?

Sure. Essentially, we will take each nerve and do the following:

- Thoroughly learn the path of the nerve

- Fascially clear the path of the nerve

- Manually lengthen supportive structures and tunnels that surround the nerve.

- Directly mobilize the nerve

- Glide the nerve

- Learn manual local regional integration techniques for the nerve after treatment

- Receive handouts for and practice home program for strengthening and increasing mobility in the path of the nerve

Join Nari at one of the following events to learn valuable evaluation and treatment techniques for sacral and lumbar nerves

Upcoming sacral nerve courses:

Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment - Winfield, IL

Oct 11, 2019 - Oct 13, 2019

Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment - Tampa, FL

Dec 6, 2019 - Dec 8, 2019

Upcoming lumbar nerve courses:

Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment - Phoenix, AZ

Jan 11, 2019 - Jan 13, 2019

Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment - San Diego, CA

May 3, 2019 - May 5, 2019