In an encouraging study sure to grab a lot of attention, researchers studying middle schoolers and the effect of mindfulness on suicidal thoughts have positive findings. We all know that middle school is a very challenging time, with students feeling pressure socially, academically, hormonally, and that family stressors can also be involved in this time of significant growth and change. If we think back to our time in middle school, we may recall some very challenging emotions, and a difficulty in seeing past our school environment and into our potential future. What if mindfulness training could provide an outlet for positive thoughts and a way to more effectively manage emotions?

In this study, highlighted in the research spotlight of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 100 sixth graders were randomized into an Asian history class with daily mindfulness practice and into an African history class with a matched activity unrelated to mindfulness or self-care. The mindfulness instruction included breath awareness and breath counting, body sensation, thoughts, and emotions labeling, and body sweeps. Silent meditation increased from 3 minutes to 12 minutes. Over the study period of 6 weeks, students were assessed for development of suicidal thoughts or self-harm behaviors.

While the researchers conclude that more studies with larger groups need to be done to validate the findings, the reports of this study are very encouraging. Keeping in mind that there are no equipment needs and little or no risk with the applied intervention, perhaps more schools will look to trainable skills in mindfulness to teach young people self-management skills. Mindfulness and meditation continue to receive significant attention in the research literature, and rightly so, as patients, providers, and family members may benefit from simple techniques that can be practiced and applied in a variety of ways.

If you would like to learn more about how to practice and to teach skills in mindfulness, sign up early for our new continuing education course called Mindfulness-based Biopsychosocial Approach to Chronic Pain. Instructor Carolyn McManus has been studying, practicing, and teaching mindfulness to patients and providers for many years. This course can be taken by any health provider, so invite your colleagues to join you at the course! If you are not yet familiar with her work or her patient resources, you may find her guided meditation and relaxation CD's a terrific tool to share or utilize yourself. You can listen to samples of the work on her website by clicking here.

One thing I have decided after working with women during and after pregnancy is this: babies come when they want, and how they want to arrive. A mother's best laid birth plans will hopefully have enough flexibility to allow her to feel successful even if, and especially if, her plans have to change. A fundamental question that has been asked, from the standpoint of a mother's beliefs is, do women really feel they have a choice to deliver at home versus in a hospital?

Researchers in the UK asked this question of a diverse sample of 41 women who were interviewed. Despite the fact that in the UK, a woman can birth at home with a midwife (and this is covered by the National Health System) home births are unusual, accounting for only 3% of all births. And while it may seem exciting to read that in the US, the number of home births has risen by more than 50% over a decade, the actual numbers include that less than 2% of births occur at home according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) data.

Back to the concept of choice, when women were interviewed about where they planned to give birth, perceptions rather than fact ruled the day. The concept of which environments were "safe" versus "risky" were a common theme, with women having differing explanations of why a hospital might be more safe than the home environment, or vice versa. The authors describe the issue that, when healthy mothers with low-risk pregnancies give birth in hospital environments, medical interventions including surgical birth are more likely to place. Women who would choose a home birth reported beliefs such as not being able to have a 'natural' birth in a hospital, fear of contracting illness or disease, or of wanting to be at home surrounded by loves ones. Women also reported that at home, more control over the environment and increased ability to relax would be available.

On the other hand, women who wanted to give birth within a hospital associated the medical environment with safety and reassurance, and expressed fear of feeling guilty if events did not turn out well with a home birth. Unfortunately, some women reported feeling "unfit" to give birth and chose the hospital as a place where both mother and the baby would be more safe. This, I believe, is a very sad statement about the disempowerment that women feel in relation to their own ability to feel healthy and strong in their own body, and to trust that the birth experience can progress well in a multitude of environments. Women interviewed in the study cited marketing and propaganda as contributing to a sense of not being healthy or fit enough to manage the birth outside of a hospital.

The authors point out that "…beliefs and assumptions about birth risk are deeply ingrained…" and that fear of the risks of birthing at home, well-founded or not, remain prevalent. So what is our role? Perhaps to share that healthy women who have uncomplicated pregnancies have choices, and that we believe in their ability to make positive, strong choices that their bodies are fit to perform. There are many birthing centers that are designed with home comforts, and that offer a "middle ground" between a hospital center and a home environment. Home births can be attended by well-trained midwives or other practitioners who are experienced in knowing when and how to access more interventional approaches if needed. This post is not about whether a woman should give birth at home or in a hospital- that issue is hotly debated by many forums currently and by experts in the topic. What we as pelvic rehabilitation providers can continue to offer is coaching, encouragement, and education that is empowering to a woman, so that when she makes a decision (in conjunction with her chosen providers) about how she would like the birth of her child to be achieved, she feels "fit" to birth in the environment she chooses.

If you agree that we have a role in providing a platform from which we educate and empower women to trust their bodies and their choices about birthing, then you will L.O.V.E taking a course with Ginger Garner, a very empowered (and empowering) woman who is a relentless advocate of these issues. In New York, in November, you can take Ginger's continuing education course Yoga as Medicine for Pregnancy. Watch for future Yoga as Medicine courses from Ginger to be updated on our schedule in the coming weeks. Can't make a live course right now? Check out Ginger's online courses with Medbridge, and take advantage of the Herman Wallace discount on our website!

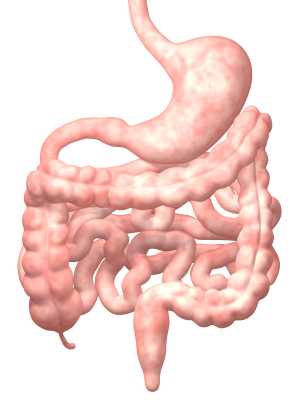

A recent article describing the impact of psychological factors on bowel dysfunction describes several mechanisms by which this may occur. Issues cited that may influence the bowels include psychological stress, which can lead to nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and changes in bowel patterns or habits. Stress can also affect the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, or HPA axis. This axis is a major part of the neuroendocrine system that, in addition to controlling stress reactions, regulates many body functions such as digestion and immunity. During stress, cortico-releasing factor (CRF) can also be released, and act directly on the bowels or via the central nervous system. The authors point out that CRF can also affect the microbiota composition within the gut.

Corticotrophin-releasing factor can affect gut motility, permeability, and inflammation. The way in which motility is affected can vary, from increased movement of bowel contents to more sluggish movement, depending "…on the type of CRF family receptor expressed on the target organ." Gut permeability can also be affected by CRF, leading to bowel hypersensitivity and other issues such as nutritional absorption dysfunction. Stress-associated inflammation is also of concern, with markers of inflammation being found in patients who have irritable bowel syndrome and other conditions. Dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance, can be caused by stress, leading to changes in bowel motility , inflammation, and permeability, according to the referenced article. Diet-induced dysbiosis, discussed in this article, can lead to inappropriate inflammation and to cellular damage and autoimmunity, making a person vulnerable to chronic disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Such disease conditions may include ulcerative colitis, Chrohn's disease, celiac disease, and diabetes. Probiotics, prebiotics, and alterations in dietary intake are current therapeutic approaches, with further research needed to determine what types of interventions are most helpful for specific conditions.

Pelvic rehabilitation providers, especially those who are newer to the field, quickly discover that trying to treat pelvic dysfunction without knowledge of bowel health is like trying to treat low back pain while ignoring the pelvis: to truly ease symptoms both may need to be addressed. Patients often present with a combination of issues in the domains of bowel, bladder, sexual health and pain, and being able to address all with expertise aids in effectiveness of care. If you are interested in learning more about bowel dysfunction, faculty member Lila Abbate teaches her continuing education course "Bowel Pathology and Function" in California in early November. There is also an opportunity to learn about how to ameliorate stress and its potentially negative affects on bowel health by attending the Mindfulness-Based Biopsychological Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain taking place in Seattle in November.

According to the APTA's Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, physical therapists use a systematic process, also termed differential diagnosis, to place a patient into a diagnostic category. This diagnosis is aimed towards defining the dysfunctions that will be treated, and in determine the needs of the patient based on each individual's presentation. Rehabilitation professionals must also consider symptoms and clinical examination findings that point to a need for other health care providers' involvement. In pelvic rehabilitation, this becomes a challenging process. In an article in Canadian Family Physician, physicians Bordman & Jackson list conditions that can cause chronic pelvic pain, and these conditions cover a variety of body systems and conditions. For example, bladder, bowel, or gynecologic malignancies, endometriosis, pelvic congestion, interstitial cystitis, urethral syndrome, constipation, inflammatory or irritable bowel syndrome can all cause pelvic pain. Abdominal wall or pelvic floor muscle myofascial trigger points, coccyx pain, neuralgia, and even depression can be other sources for pain. Certainly, it is uncommon to find only one source of pain in our population of patients with chronic pelvic pain.

Within a multidisciplinary approach, which is more often the recommended approach to treating chronic pelvic pain, physical therapy will ideally work with other practitioners to develop the best course of care for the patient. In my professional experience mentoring students and therapists, once a pelvic rehabilitation provider has learned basic skills and has treated many patients, the therapist develops a keen interest in improving skills of differential screening. The ability to diagnose requires learning which keys unlock certain doors, whether from an organs systems standpoint or a musculoskeletal standpoint. The Institute offers several courses that focus on the ability of a therapist to test specific tissues and movement patterns to determine the most appropriate plan of care. Steve Dischiavi's Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip and Pelvis includes a sports medicine approach to evaluating and treating hips and pelvic dysfunction, which can often confound one another. Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain is another popular course instructed by faculty member Elizabeth Hampton and the course emphasizes pelvic pain and the musculoskeletal co-morbidities that often accompany pelvic floor dysfunction. More dates are being scheduled for these 2 continuing education courses, sign up early to hold your spot!

You still have an opportunity to take Peter Philip's Differential Diagnostic of Chronic Pelvic Pain & Dysfunction this course takes place in Connecticut in mid-October. In this course, Peter emphasizes anatomical palpation, nervous system influence on pelvic pain, and biomechanical examination of nearby joints and tissues. Internal labs are included in this 2-day continuing education course. If you are interested in hosting any of these courses, contact the Institute today to get the process started!

Male chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is well-known to be associated with sexual health impairments including, but not limited to, pain limiting sexual activity, premature ejaculation, erectile dysfunction. In addition to potential interference in sexual activity due to pelvic pain associated alteration in libido and function, does CPP affect sperm health? According to a systematic review and meta-analysis published this year, semen parameters are impacted in men who present with chronic pelvic pain. 12 studies were utilized, including nearly 999 cases and 455 controls. Semen parameters studied included seminal plasma volume, sperm concentration, total sperm count, motility, vitality, and morphology. Men diagnosed in the studies with CPP or chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) met the NIH criteria for the condition.

The results of the analysis indicate that sperm concentration, percentage of progressively motile sperm, and morphologically normal sperm in patients with CPP/CPPS were significantly reduced when compared with controls. Semen volume was higher in the CPP pain group than in controls, and the results suggested no significant difference in sperm total motility, sperm vitality, and total sperm count. How do these factors affect fertility? The authors point out that semen parameters are "the mainstay of male fertility and reproductive health assessment" and and that the percentage of morphologically normal sperm is an indicator of male fertility potential. While the sperm concentration was identified to be lower in male patients who have CPP, the semen volume being elevated may affect these numbers. Sperm motility, being necessary for fertilization, would logically be a factor in potential impairment of fertility.

The authors discuss the possibility that an inflammatory response associated with chronic pelvic pain, or an autoimmune response against prostate specific antigens factor into the alterations in semen analysis observed in men who have chronic pelvic pain. While the issue of fertility and pelvic pain is controversial, and not entirely understand, we can hypothesize about local factors affecting pelvic and sexual health, as well as autonomic nervous system implications mediated by the chronic pain state. As science aids in the understanding of the mechanisms affecting semen parameters, pelvic rehabilitation professionals will continue to address the potential causes of the dysfunction: nervous system dysfunction such as anxiety, depression, hormonal regulation, and neuromuscular pain states that may affect local blood and lymph flow (and therefore affect cellular nutrition and removal of waste products of cellular metabolism). If you are interested in learning more about male anatomy, sexual dysfunction, pelvic pain, and incontinence, come to the Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, & Treatment continuing education course in Tampa in October!

This post was written by H&W instructor Allison Ariail PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, BCB-PMD. Allison will be instructing the Pelvic Floor Level 1 course Boston this October.

Several weeks ago some of my fellow faculty members and I were discussing the resting tone of the pelvic floor. These days we take it for granted that we know there is constant low-level activity in the pelvic floor and anal sphincter in order to provide continence. However, how did this information come about? I took it upon myself to do some research to find out the beginnings of this knowledge. What I found was interesting and thought I would share.

In the late 1940’s and early 1950’s the belief was held that the pelvic floor and external anal sphincters were inactive at rest, like other striated muscle throughout the body. Activity was believed to be initiated by afferent impulses from the rectal ampulla and anal canal. In 1953 Floyd and Walls found activity in the external anal sphincters at rest, even during sleep. In 1962 Parks, Porter, and Melzak published a study examining the pelvic floor muscles and the external anal sphincters using electromyography recordings. They also found activity in these muscles at rest. They hypothesized the activity was maintained by spinal reflex. These researchers looked at the activity in a healthy population, a paraplegic population, and a population that had undergone a rectal excision. When examining the paraplegic population (all subjects had complete SCI injuries above L3), they did identify activity of the pelvic floor at rest.

With respects to the rectal excision population, they examined patients whose rectums were removed, but the somatic muscles, external sphincters, and the levator ani remained with innervation intact and the muscles were sutured to provide a muscular pelvic floor. These patients also exhibited activity in the pelvic floor and anal sphincter at rest. These patients were important to the study in order to rule out that the reflex was not coming from somewhere in the rectal wall. Additionally, these researchers discovered this resting activity that was present the anal sphincter was inhibited during defecation in response to a certain degree of rectal distension.

So what did all of this new information mean to these researchers? It meant that the pelvic floor and external anal sphincter were unique due to the fact they were activated at rest, and without this activation continence would not be maintained. They determined the activation to be reflex and termed it “postural reflex of the pelvic floor.” Additionally, they termed the inhibition due to rectal distension “the rectal inhibitory reflex,” which also was due to a reflex arc. This new information was groundbreaking for the time and lead to other research that provided us with the knowledge that we have today! Thank goodness for these researchers as well as the many others who have furthered the advancement of knowledge about the pelvic floor!

Learn more about Allison and the Pelvic Floor Series by visiting our website!

1. Floyd, Walls. Electromyography of sphincter ani externus in man. J. Physiol. 122: 599, 1953.

2.Parks, Porter, Melzak. Experimental study of the reflex mechanism controlling the muscles of the pelvic floor. Dis. Colon Rectum. 5 (6): 407. 1962.

This post was written by H&W instructor Carolyn McManus, PT, MS, MA. Carolyn will be instructing the course that she wrote on "Mindfulness-Based Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain" in Seattle this November.

I have taught Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction at Swedish Medical Center (SMC) since 1998. Over the years I have had many healthcare providers take the course and have long thought it would be wonderful to tailor a program specifically for healthcare professionals. I had the opportunity to do so this summer when, along with my colleague Diane Hetrick, PT, we designed and taught Mindfulness and Compassion Cultivation Training for physicians at SMC. The course was a great success. Physicians reported one of the most popular components of the program were our “on the spot” mindful practices. These are simple, easy-to-do strategies that any provider can employ to center, calm the body and steady the mind during a busy workday. They not only help reduce stress, but can influence brain activation to promote better decision making.

Research shows, under stress conditions, the amygdala activates stress pathways in hypothalamus and brainstem, evoking high levels of noradrenaline and dopamine release, impairing prefrontal cortex function. (1) Research also shows mindful practices reduce stress-related brain activity and improve executive functioning. (2, 3) I am delighted to share these powerful and practical “on the spot” mindful practices in my November course. My intention is for participants to have mindfulness skills to use for their own well-being the minute they walk in their clinic door on Monday.

Learn more about Carolyn's course Mindfulness-Based Biopsychosocial Approach to Chronic Pain and join her in Seattle this fall!

1. Arnsten AF. Stress signaling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009:10(6):410-422.

2. Holzel BK, Carmody J, Evans KC, et al. Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010;5(1):11–17.

3. van den Hurk PA, Giommi F, Gielen SC, et al. Greater efficiency in attentional processing related to mindfulness meditation. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove) 2010;63(6);1168–1180.

When a woman is interested in a trial of labor after previous cesarean delivery (TOLAC), she and her health care providers will consider the pros and cons of delivery methods. Researchers have aimed to predict success with vaginal birth after cesarean section (CS), with the intention of limiting the risk factors for both the mother and the fetus. A failed trial of labor following a CS may be associated with higher maternal and perinatal morbidity, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) practice bulletin.

The goal of a study published last year was to develop a model for predicting success in women desiring a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) section. All women had one prior CS, all were carrying singletons. Transvaginal ultrasound was utilized to evaluate the Cesarean scar (CS) at 11-13, 19-21, and 34-36 weeks' gestation in 320 women. The measurement of the scar was termed residual myometrial thickness (RMT), and the measurements also included the change in RMT from the 1st to 2nd trimester. With increased evidence that CS healing and myometrial thickness in the lower uterus may improve success with VBAC, this study is the first to assess scar dimensions across the first and second trimesters.

The CS scar was visible in 89% of the women. Of these, 153 of the 284 were excluded from the prediction model development due to having had more than one prior cesarean delivery, so the hospital protocol of scheduling cesarean was followed. The remaining women were offered a vaginal birth trial, with 10 of the 131 undergoing CS prior to labor for varied reasons. The final count of women included in the analysis was 121, and of these cases, 74 had successful VBAC, 47 experience failed trials of labor, primarily due to fetal distress, failure to progress, or possible scar rupture. (In the women who did not have a visible scar, 82% had a successful vaginal delivery.)

The median residual myometrial thickness, or RMT, was higher in patients who had a successful VBAC. Clinical usefulness, according to the study, is that use of the model may lead to fewer emergency CS deliveries through identification of women who will be successful with VBAC.

The authors concluded that measurements of a CS, when applied to a mathematical model, can predict success of a vaginal birth after CS. This information may be very interesting to discuss with our referring providers, our colleagues, as well as our patients. Any research that sheds light on variables to predict success with a VBAC may promote vaginal deliveries and hopefully prevent emergency cesarean deliveries. Educating our patients so they can be more informed and advocate for themselves is a key role. While we are always mindful of not overstepping our scope of practice, such as advising a woman if she should choose one method of delivery over another, the information about the scar thickness in predicting VBAC success may be very useful to both her and providers. For more information about peripartum issues, check out our Peripartum Course Series on the course page. There is still time to sign up for the Care of the Postpartum Patient continuing education course later this month in Chicago!

A systematic review aimed to identify the burden of the most significant complications of postoperative abdominopelvic adhesions. Of the nearly 200 studies included in the review, the following categories were included: small bowel obstruction (n=125), difficulties during subsequent operation (n=62), infertility (n=11), and chronic pain (n=5). The incidence of postoperative small bowel obstruction, assessed among nearly 108,000 patients in 92 studies, was 9% overall. The incidence of adhesive small bowel obstruction was 2.4% and was highest in pediatric and in lower gastrointestinal tract surgery. The authors report a high rate of chronic abdominal pain in patients who were followed after lower gastrointestinal tract surgery, with adhesions identified as a significant cause of this pain. Following colorectal surgery for small bowel disease, pregnancy rates were found to be dramatically lower than the pregnancy rates in those who were medically treated. Additionally, patients who have had a prior surgery may require additional time in a subsequent procedure due to scar tissue, and adhesiolysis, used to break up adhesions, can lead to bowel injury.

Patients with postoperative adhesions, according to the systematic review, are most often treated by providers other than the one who did the surgery; the lack of awareness of the complication may be one reason that the incidence of adhesions is underestimated. The value of being aware of the higher incidence of postoperative adhesions may be in early recognition of a complication, surgical decision-making, and patient counseling. While the research is young in relation to adhesions and pelvic rehabilitation, one study that we previously discussed in the blog addresses visceral mobilization techniques in an animal model. While the animal model research is promising, there are numerous case reports describing the positive effects of visceral mobilization techniques for abdominopelvic pain, and therapists always report on the equally positive changes to their clinical practice outcomes after adding visceral techniques to their toolbox.

There are 2 upcoming opportunities to learn visceral mobilization: Level 1 in Scottsdale covering the Urologic system and Level 2 in Boston covering the reproductive system.

One of the questions we frequently receive at the Institute is "Do you have any research about ___________?" At times, therapists are looking for information that can help with patient care, or they might be looking for support in a claims denial letter, or foundational material for a presentation. If you have been taught how to find articles, this may seem like a simple task. Many of us therapists went to school when the only use of a computer was for word processing, if we were lucky enough to have progressed from the typewriter or even the electronic typewriter. (Imagine no Google, no Wikipedia, and no Amazon to purchase textbooks!) There are basic search skills that can be shared so that every person interested in a particular topic can find recent articles in free search engines. While the full article may not be available, many times you will have access to full articles that synthesize recent works. (One website that you can use that offers full text article access is PubMed Central.) If you are not interested in reading articles, but prefer to read a scholarly summary of a health topic, check out www.uptodate.com, where you can subscribe to have full access to excellent evidence-based summaries. You can read through the reference lists on the site as well to see if there is a resource that you want to track down.

One method of finding articles is to go to www.googlescholar.com. In the search bar, type in the topic you are interested in, such as "urinary incontinence." You will then be provided with a list of all articles that have urinary and/or incontinence in the title or in the key words of the research. An even more refined way to conduct your search is by using Boolean terms, in which you connect your search words by "AND" or other key terms. To see this in action, let's say you want to know if there is any research about urinary incontinence and prostatectomy surgery. Try completing a google scholar search by typing in the following: "urinary incontinence" AND "prostatectomy". (Be sure to use the quotation marks and type the word "AND" in capital letters.) You will see that you come up with some very nice articles about the specific topic you searched. To make sure you are looking at recent articles, go to the left side of the search page and under the words "Any time" choose an option such as "Since 2010" so that you are seeing articles from within the last 5 years. Next, maybe you want to know if there is evidence for rehabilitation. Add the word rehabilitation, like this: "urinary incontinence" AND "prostatectomy" AND "rehabilitation". You will see that you now have even more results specific to rehabilitation of the condition. On the right side of the page you might see a link that starts with [PDF] where, if you click on it, you will usually be brought to the full article rather than just the abstract. If you see an article that you think fits your search, you can also click on "Related articles" located under the brief description of the article.

Being able to look up articles serves many purposes, including staying updated on patient care, and discussing evidence with peers, providers, and patients. Another valuable reason to find your own research is when studying for certification exams such as the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification (PRPC). On the PRPC certification page on our website, you can find a list of some articles for which we have added links. (Remember that there is no need to print out articles anymore! Save a tree and simply save the articles as a PDF file. You can name the article by the author's last name, year and main topic, and store in a folder on your computer so it is easy to access- no file drawer required!) If you are thinking about taking the PRPC exam, there is no time like the present to get your application put together! The deadline for applying is October 1 of this year, with the test taking place in the first couple weeks of November. Personally, I have enjoyed reading the blog posts introducing therapists who have earned their PRPC title- the reasons for seeking the distinction are very interesting and meaningful. We would love to see your name on the list of certified therapists, so check out the details on the website and contact us if you have any questions about the PRPC application process!

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./