Everyday we as pelvic rehab providers get to help patients achieve their goals by meeting them where they are and guiding them along.

A couple of months ago I had a new patient come in to see me who was seven months status post c-section delivery of her first child. She was referred to physical therapy because she could not tolerate anything touching her lower abdomen and she was also unsure of how to start exercising again including returning to her yoga practice. I remember reading her referral and thinking that this should be a simple evaluation and treatment session. What actually happened was a little different.

Her delivery hadn’t gone the way she planned, and she was not comfortable discussing it at our first session. This patient had not looked at or touched her c-section incision besides drying it off after her shower for the seven months since delivery. Her physician had made a referral to PT and to a counselor within three months of delivery to help support the patients’ recovery. The patient had not followed through with the PT referral until she had significant encouragement from her counselor and physician.

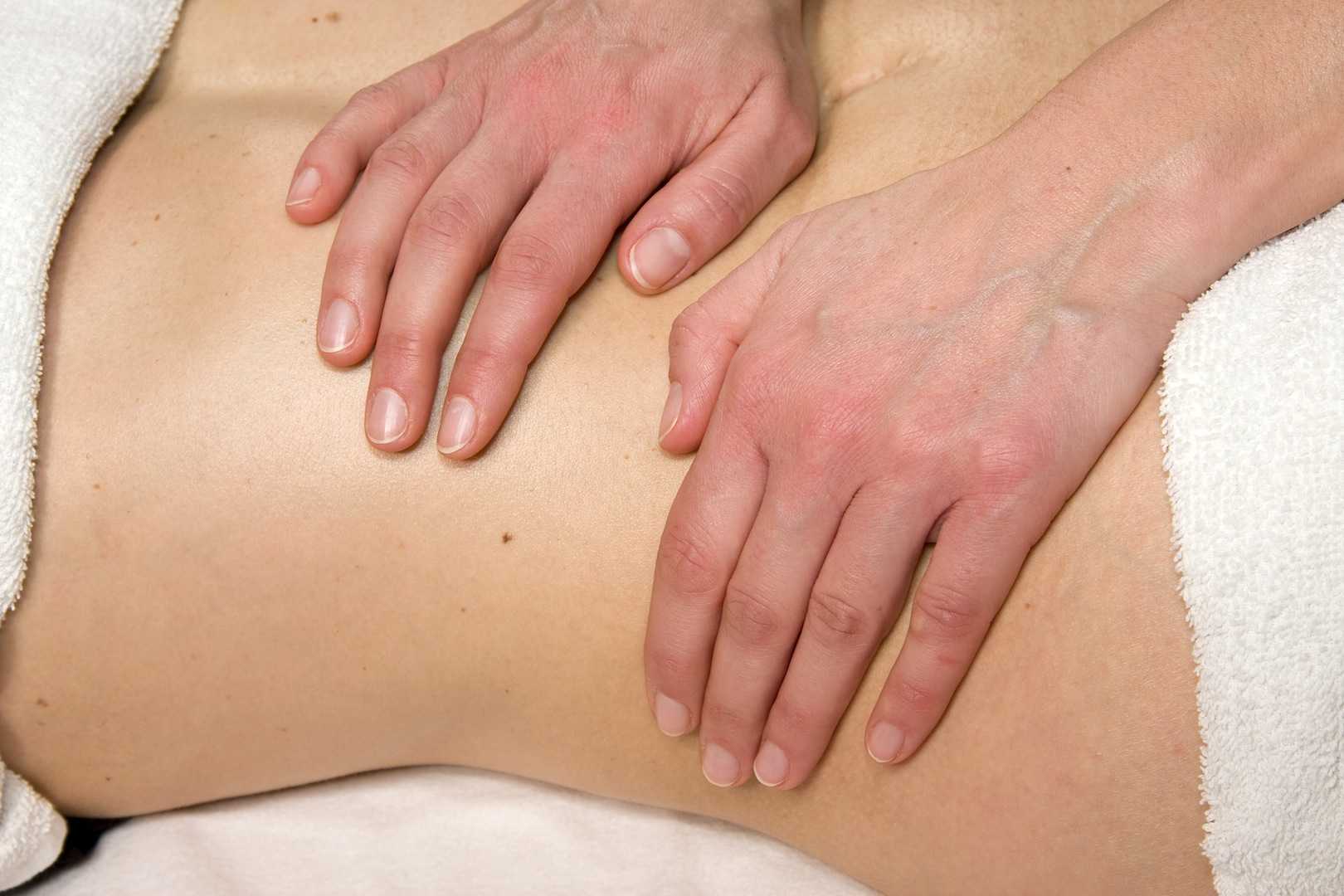

Initially the patient declined any observation or palpation of her abdomen so at our first session we focused on thoracic range of motion, general posture, and encouraged her to start touching her abdomen through her clothes, even if avoiding direct touch to the incisional region. The patient was agreeable with this starting point. At the second session the patient was willing to have me look at her abdomen and touch the abdomen but she declined direct palpation of the scar region. With simple observation I could see a scar that was closed and healing but also that was pulled inferior towards her pubic bone. She was not comfortable laying flat on the treatment table and had to be supported in a semi-recline throughout the session. She also described buzzing symptoms at the scar region when she reached her arms overhead.

We started some gentle desensitization techniques as would be used with a person that had Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) after an injury. I focused those treatments to the abdominal region but avoided the scar region. We focused her home program on breathing into her abdomen allowing some stretch and expansion of the abdominal region. Her home program also included laying flat for five minutes per day. I asked her to notice any general tension throughout her body during the day and attempt to change it and release it if able.

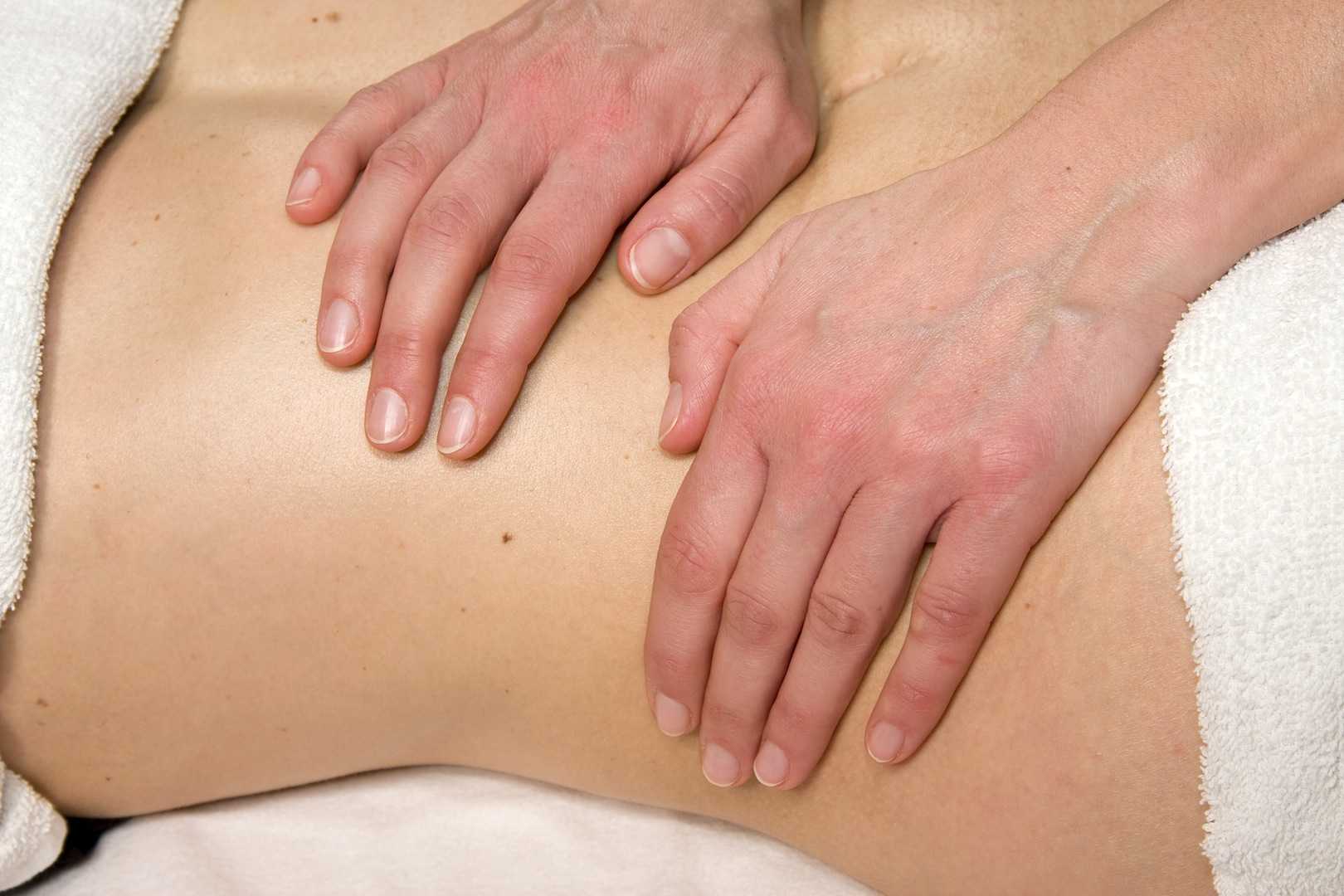

By the fourth session we where able to begin direct palpation and manual therapy techniques to the c-section scar and the whole abdominal region. The patient was apprehensive but agreed to proceeding with utilizing techniques as described by Wasserman et al2018 including superficial skin rolling, direct scar mobilization and general petrissage/effleurage of the abdomen and lumbothoracic region.

Over the next five sessions the patient was able to start wearing undergarments and pants that touched her lower abdomen. She was able to perform her own self massage to the region and began an exercise program including prone press ups, progressive generalized trunk strengthening, and return to her prior-to-pregnancy yoga practice.

Drawing on the techniques we learn from multiple sources, applying them to the lumbopelvic region, and helping our patients wherever the client is in their journey to wellness, is what inspires me to keep learning.

Techniques like this are taught in my 2-day Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist course. I specifically wrote this course so that pelvic rehab therapists that are looking for more techniques and/or more confidence in their palpation skills would have a weekend to hone those skills. We spend time learning anatomy, learning palpation skills, manual techniques, problem solving home programs and discussing cases. Check out Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist - Raleigh, NC - June 22-23, 2019 for more information and I hope to see you there.

Wasserman, J. B., Abraham, K., Massery, M., Chu, J., Farrow, A., & Marcoux, B. C. (2018). Soft Tissue Mobilization Techniques Are Effective in Treating Chronic Pain Following Cesarean Section: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 42(3), 111-119.

The following is a guest submission from Alysson Striner, PT, DPT, PRPC. Dr. Striner became a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) in May of 2018. She specializes in pelvic rehabilitation, general outpatient orthopedics, and aquatics. She sees patients at Carondelet St Joesph’s Hospital in the Speciality Rehab Clinic located in Tucson, Arizona.

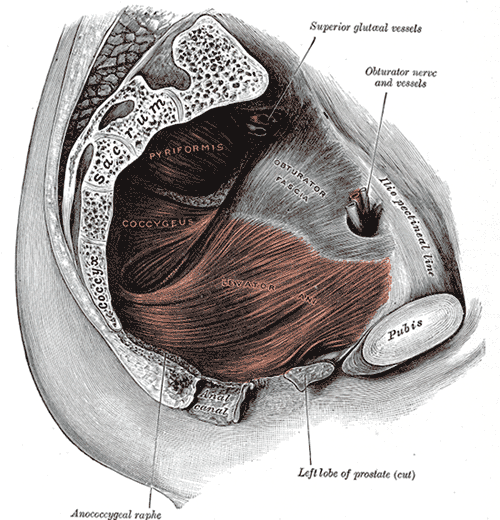

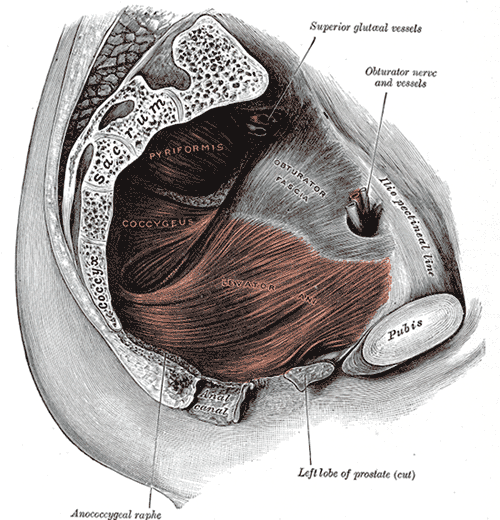

Myofascial pain from levator ani (LA) and obturator internus (OI) and connective tissues are a frequent driver of pelvic pain. As pelvic therapists, it can often be challenging to decipher whether pain is related to muscular and/or fascial restrictions. A quick review from Pelvic Floor Level 2B; overactive muscles can become functionally short (actively held in a shortened position). These pelvic floor muscles do not fully relax or contract. An analogy for this is when one lifts a grocery bag that is too heavy. One cannot lift the bag all the way or extend the arm all the way down, instead the person often uses other muscles to elevate or lower the bag. Over time both the muscle and fascial restrictions can occur when the muscle becomes structurally short (like a contracture). Structurally short muscles will appear flat or quiet on surface electromyography (SEMG). An analogy for this is when you keep your arm bent for too long, it becomes much harder to straighten out again. Signs and symptoms for muscle and fascial pain are pain to palpation, trigger points, and local or referred pain, a positive Q tip test to the lower quadrants, and common symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, pain, and/or dyspareunia.

For years in the pelvic floor industry there has been notable focus on vocabulary. Encouraging all providers (researchers, MDs, and PTs) to use the same words to describe pelvic floor dysfunction allowing more efficient communication. Now that we are (hopefully) using the same words, the focus is shifting to physical assessment of pelvic floor and myofascial pain. If patients can experience the same assessment in different settings then they will likely have less fear, and the medical professionals will be able to communicate more easily.

A recent article did a systematic review of physical exam techniques for myofascial pain of pelvic floor musculature. This study completed a systematic review for the examination techniques on women for diagnosis of LA and OI myofascial pain. In the end, 55 studies with 9460 participants; 99.8% were female, that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed. The authors suggest the following as good foundation to begin; but more studies will be needed to validate and to further investigate associations between chronic pelvic pain and lower urinary tract symptoms with myofascial pain.

The recommended sequence for examining pelvic myofascial pain is:

- Educate patient on examination process. Try to ease any anxiety they may have. Obtain consent for an examination

- Ask the patient to sit in lithotomy position

- Insert a single, gloved, lubricated index finger into the vaginal introitus

- Orient to pelvic floor muscles using clock face orientation with pubic symphysis at 12 o'clock and anus at 6 o'clock

- Palpate superficial and then deep pelvic floor muscles

- Palpate the obturator internus

- Palpate each specific pelvic floor muscle and obturator internus; consider pressure algometer to standardize amount of pressure

Authors recommend bilateral palpation and documentation of trigger point location and severity with VAS. They recommend visual inspection and observation of functional movement of pelvic floor muscles.

The good news is that this is exactly how pelvic therapists are taught to assess the pelvic floor in Pelvic Floor Level 1. This is reviewed in Pelvic Floor Level 2B and changed slightly for Pelvic Floor Level 2A when the pelvic floor muscles are assessed rectally. Ramona Horton also teaches a series on fascial palpation, beginning with Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremity. I agree that palpation should be completed bilaterally by switching hands to make assessment easier for the practitioner who may be on the side of the patient/client depending on the set up. This is an important conversation between medical providers to allow for easy communication between disciplines.

Meister, Melanie & Shivakumar, Nishkala & Sutcliffe, Siobhan & Spitznagle, Theresa & L Lowder, Jerry. (2018). Physical examination techniques for the assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain: a systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 219. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.014

Dr. Nicole Cozean was just awarded the IC/BPS Physical Therapist of the Year by the IC Network, one of the largest patient advocacy groups for interstitial cystitis! Today she shares her treatment approach for this complex dysfunction. Join Dr. Cozean in San Diego on April 28-29, 2018 to learn everything there is to know about interstitial cystitis.

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a chronic pelvic pain condition characterized by pelvic pain and urinary urgency/frequency. IC is frequently accompanied by other symptoms1, including painful intercourse, low back or hip pain, nocturia, and suprapubic tenderness.

While pelvic floor physical therapy is the most proven treatment for interstitial cystitis, most patients require a multi-disciplinary approach for optimal results. The majority are forced to develop this holistic approach on their own, but one of the most valuable things a physical therapist can provide is assistance in creating their own unique treatment plan. The American Urological Association has released treatment guidelines for interstitial cystitis, and potential treatments fall into several different categories. It is important to note that most treatments aren’t effective for the majority of patients, so a trial-and-error approach is needed to find the right balance for each patient. Tracking symptoms with a weekly symptom log can be a powerful tool to optimize the individual treatment plan.

Summary of the AUA Guidelines for IC – Download Here

Oral Medications

Oral medications are primarily used to reduce pain.Anti-depressants can dampen the nervous system, decreasing the severity of pain reported. Anti-histamines have also been shown to be effective in reducing the pain and symptoms of interstitial cystitis, perhaps because of their ability to reduce inflammation and break the cycle of dysfunction-inflammation-pain (the DIP cycle). Some patients require opioid painkillers for adequate pain control.

Urinary tract analgesics can provide temporary pain relief for some patients, but cannot be taken consistently because they thicken the urine and strain the kidneys. Some patients find success using these medications (Azo, Pyridium, Uribel) during severe pain flares.

The only FDA-approved oral treatment for interstitial cystitis is Pentosan Polysulfate (PPS, Elmiron®). This is commonly prescribed to patients after an IC diagnosis, but has been shown to be effective in only 28-32% of patients. It also requires a long time (often 6-9 months) to build up in the system and take effect, and many patients stop taking the drug before they could see effect because of side effects (including hair loss) or cost. Unfortunately, many patients lose more than a year after their initial diagnosis waiting to see if Elmiron will work for them, when it is unlikely to provide complete relief.

Antibiotics should never be prescribed for IC in the absence of a confirmed infection.

Bladder and Medical Procedures

Bladder instillations deliver numbing medication directly to the bladder through a catheter and can provide temporary pain relief for some patients. If these are effective, they typically are repeated at least weekly as symptoms return. Some patients don’t tolerate the catheterization well, finding the procedure causes more pain than it prevents. Typical bladder instillations consist of Lidocaine, Heparin, or a combination of the two.

Another route of treatment works by artificially stimulating the nerves the innervate the bladder and pelvic floor.Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) directs electrical impulses from the ankle up through the pelvic floor. This is an outpatient procedure typically performed weekly for a course of 12 weeks. A more permanent option is implanting a device under the skin of the buttock to target the sacral or pudendal nerve root directly.With this procedure, the patient is given a ‘trial run’ with an external device to see how it performs. If significant improvements are noted, the device can be permanently implanted.

Many patients see marked improvement in their symptoms with a home care program. Deep breathing or meditation can calm the nervous system and reduce the amplifying effect of an upregulated nervous system. A stretching regimen targeting the inner thighs, glutes, abdomen, and pelvic floor can relax muscles and reduce nerve irritation in the region. Self-massage can find and eliminate the trigger points that are causing symptoms. Home tools like a foam roller can address external trigger points, while patients can be taught internal self-release with the help of a tool like the PelviWand or another tool.

Elimination Diet

One of the most common misunderstandings about IC centers on the ‘IC Diet.’ In fact, there’s no such thing. While nearly 90% of IC patients report that diet influences their symptoms in some way, the scope and severity of dietary triggers varies greatly between patients. There are a few common culprits - coffee, tea, citrus fruits, artificial sweeteners, tomatoes, cranberry juice - but no guarantee that a patient will be sensitive to all (or any) of these. Many patients read about an ‘IC Diet’ online after receiving their diagnosis, and are convinced that they need to cut out a huge portion of their diet.

Instead, they should be doing an elimination diet focused on identifying their trigger foods.With this approach, they eliminate most of those common culprits and see how it affects their symptoms.If they notice an improvement, they can gradually add foods back into their diet, one at a time, until they see symptoms increase again. This allows patients to identify their specific trigger foods.

Our advice for IC patients is simple - avoid your trigger foods and eat healthy. It doesn’t have to be any more restrictive than that.

There are also several supplements that have shown benefit for patients, either in clinical trials or anecdotally. Prelief (calcium glycerophospate) is an antacid that may reduce the consequences of eating a trigger food. L-Arginine is a semi-essential amino acid that facilitates blood flow and vasodilation; in clinical trials it was shown to be effective for nearly 50% of patients in reducing pain and urinary symptoms. Aloe Vera pills are used by many patients, and thought to help replenish the bladder’s protective layer. Finally, a combination of supplements known as Cystoprotek is also a common supplement taken by IC patients, combining anti-inflammatory flavonoids with molecules that may reinforce the bladder lining.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Acupuncture has been shown to provide relief for pelvic pain patients2, with 73% of men with chronic prostatitis (either identical or closely related to IC) reporting improvement. These men received two treatments weekly for six weeks, focusing around the sacral nerve. Women with pelvic pain and painful intercourse have also reported improvements in pain with 10 sessions of acupuncture3.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been shown to help reduce pain in conditions as diverse as cancer, low back pain, and pelvic pain. In pelvic pain, ten one-hour sessions of CBT was shown to provide significant benefit for nearly half of patients4. Supportive psychotherapy was also shown to have benefits for pelvic pain patients.

A multi-disciplinary approach provides the best results for patients. Physical therapists, who see our patients regularly, can be a great resource in suggesting additional treatment options. The American Urological Association IC Guidelines can be an important resource in guiding patients to other options and developing their unique treatment plan.

Information and Resources

For additional patient resources available for download, feel free to visit The IC Solution page.. In our upcoming course for clinicians treating interstitial cystitis (April 28-29, 2018 in San Diego), we’ll focus on the most important physical therapy techniques for IC, home stretching and self-care programs, and information to guide patients in creating a holistic treatment plan.

1. Cozean, N. "Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy in the Treatment of a Patient with Interstitial Cystitis, Dyspareunia, and Low Back Pain: A Case Report". Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 2017

2. Chen R, Nickel JC. "Acupuncture ameliorates symptoms in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome"Urology. 2003 Jun;61(6):1156-9; discussion 1159.

3. Schlaeger, J, et al. "Acupuncture for the Treatment of Vulvodynia: A Randomized Wait‐List Controlled Pilot Study". Journal of Sexual Medicine. 30 January 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12830

4. Masheb, et al. "A randomized clinical trial for women with vulvodynia: Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs. supportive psychotherapy". PAIN® Volume 141, Issues 1–2, January 2009, Pages 31-40

A 2016 study by Kaori et al examined the effect of self administered perineal stimulation for nocturia in elderly women. A prior study using rodents found a soft roller used decreased overactive bladder syndrome (OAB), but a hard roller did not produce the same results. Kaori et al performed a similar study for elderly women in a randomized, placebo controlled, double blind crossover. Participants were 79-89 years old women who applied simulation to perineal skin for 1 minute at bedtime, using either active (soft, sticky elastomer) roller or a placebo (hard polylestrene roller). Participants did a 3-day baseline, followed by 3-day stimulation, then 4 days rest, then other stimuli for 3 days. There were 24 participants, 22 completed the study: 9 with OAB, 13 without OAB. The placement of the roller was not on the skin of the perineal body, but rather on the general peri-anal area with the diagram from the study showing an area just medial to the gluteal crease—where one would find the ischial tuberosity-- and anterior and lateral to the anal sphincter.

Across the subjects with OAB, change with the elastomer roller (soft and sticky feel) was more statistically significant than with the hard roller. Baseline micturition for the participants was 3.2+/- 1.2 times per night, measured as the number of urination between going to bed and arising. The group as a whole did not have a statistically significant difference, measured by at least one less time arising per night. However, in the OAB group, the difference was significant. The researchers theorized that the soft and sticky texture may induce more firing of somatic afferents nerve fibers.

Across the subjects with OAB, change with the elastomer roller (soft and sticky feel) was more statistically significant than with the hard roller. Baseline micturition for the participants was 3.2+/- 1.2 times per night, measured as the number of urination between going to bed and arising. The group as a whole did not have a statistically significant difference, measured by at least one less time arising per night. However, in the OAB group, the difference was significant. The researchers theorized that the soft and sticky texture may induce more firing of somatic afferents nerve fibers.

The most commonly prescribed treatment for overactive bladder is anticholinergic therapy, but the side effects, including cognitive changes and lack of significant difference from controls, as well as the drying effect of these drugs in a post-menopausal-low-estrogen-pelvis, bring up questions of whether this is the best option in the elderly.(6)

In anesthetized animals, electrical stimulation and noxious stimuli decrease frequency of bladder contractions when applied to the perineal area (3-5). Somatic, afferent nerve stimuli (those theorized to be active with the soft roller) are used to treat OAB by modalities such as acupuncture and transcutaneous electrical stimulation to the perineum (2). So, stimulation of somatic visceral afferent nerves in the perineal region seems to have an effect on the bladder. However, with manual therapies, it seems we can also affect the somatic or visceral afferents. Essentially, visceral afferents convey information to the central nervous system about local changes in chemical and mechanical environments of a number of organ systems(7). Doing manual therapy between the urethral and bladder fascia would also theoretically cause stimulation of the visceral afferents to the central nervous system about that organ (bladder).

In our pelvic floor intro class (Pelvic Floor Level 1) at Herman Wallace, we discuss the role of Bradley’s neurology loop 3 and the inverse relationship between pelvic floor contraction (lifting the perineal area) and the bladder. One suppression technique we discuss is the contraction of the pelvic floor to quiet or inhibit bladder activity in the bladder retraining program. Bladder retraining has evidence level A (strong) for improving urgency and frequency with overactive bladder.

Clinicians who are ready to raise their manual game may try using the skills of prior series courses and adding the sophistication of manual techniques in the abdomen and pelvis to increase afferent firing in patients with OAB, as well as freeing up any fascial restrictions that may be interfering with full bladder excursion.

In the newly written Capstone course, we combine the prior level of education from the pelvic series (bladder strategies) with manual techniques to address the endopelvic fascia at the bladder base, in the fascial articulations along the perineum, and along its attachments to the coccyx, as well as combining internal work with sacral techniques to facilitate S234 afferents for bladder control. We discuss studies, such as this one, to explore advanced concepts of bladder and urethral fascial mechanics and neural entrapment affecting the bladder. We move out of the pelvic muscle and into the fascial contents of the abdominopelvic region, to allow such firing of the somatic afferents. And the perineal stimulation? We have an entire lab for perineal tissue and its effect on pelvic function. Physical therapists can manually address the perineum, urethral and bladder fascia with Capstone techniques. With such intervention, we get more CNS communication.

So, what about the roller? Well, the soft roller created change in rodents in a couple of studies. (Sato 2010). In this human study, it helped with OAB. Certainly, manual therapies in the region of the endopelvic fascia and suprapubic region may be of help for also stimulating the visceral afferents. Also, it could be worth it to have a high fall risk elderly patient with OAB type nocturia follow up your treatments with one minute of soft washcloth stroking in the area of the perineum for one minute at bedtime to see if it helps decrease the number of voids on a night time bladder diary.

Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC is a Herman & Wallace faculty member who helped author the Pelvic Floor Series Capstone: Advanced Topics in Pelvic Rehab course. She is also the creator and instructor of Pelvic Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment.

Main study: PLoS One. 2016 Mar 22;11(3):e0151726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151726. eCollection 2016.Effects of a Gentle, Self-Administered Stimulation of Perineal Skin for Nocturia in Elderly Women: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Crossover Trial.Iimura K1,2, Watanabe N2, Masunaga K3, Miyazaki S1,2,4, Hotta H2, Kim H5, Hisajima T1,4, Takahashi H1,4, Kasuya Y3.

2. Exp Ther Med. 2013 Sep;6(3):773-780. Epub 2013 Jul 9., Acupuncture for the treatment of urinary incontinence: A review of randomized controlled trials.Paik SH1, Han SR, Kwon OJ, Ahn YM, Lee BC, Ahn SY.

3. Guo ZF. Transcutaneious electrical nerve stimulation in the treatment of patients with poststroke urinary incontinence. Clin Interv Aging. 2014; 851-6.

4. Sato A, The impact of somatosensory input on autonomic functions. Reve Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;130;1-328

5. Sato A. Mechanism of the reflex inhibition of micturition conractions of the urinary bladder elicited by acupuncture-like stimulation in anesthetized rats. Neurosci res. 1992 15:189-98

6). Effects of a Gentle, Self-Administered Stimulation of Perineal Skin for Nocturia in Elderly Women: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Crossover Trial. Iimura K, Watanabe N, Masunaga K, Miyazaki S, Hotta H, Kim H, Hisajima T, Takahashi H, Kasuya Y. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 22;11(3):e0151726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151726. eCollection 2016.

7) John C. Longhurst, Liang-Wu Fu, in Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System (Third Edition), 2012

What if we were only taught treatment techniques during our healthcare training with no theory or explanation as to why or on whom or under what circumstances they should be used? Focusing on “how to” but ignoring the “discernment as to why” would make for a weak clinician. Manual therapy for the pelvic floor is a treatment approach to implement once we have used our heads and palpation skills to reveal the underlying source of dysfunction.

Pastore and Katzman (2012) published a thorough article describing the process of recognizing when myofascial pain is the source of chronic pelvic pain in females. They discuss active versus latent myofascial trigger points (MTrPs), which are painful nodules or lumps in muscle tissue, with the latter only being symptomatic when triggered by physical (compression or stretching) or emotional stress. Hyperalgesia and allodynia are generally present in patients with MTrPs, and muscles with MTrPs are weaker and limit range of motion in surrounding joints. In pelvic floor muscles, MTrPs refer pain to the perineum, vagina, urethra, and rectum but also the abdomen, back, thorax, hip/buttocks, and lower leg. The authors suggest detecting a trigger point by palpating perpendicular to the muscle fiber to sense a taut band and tender nodule and advise using the finger pads with a flat approach in the abdomen, pelvis and perineum. They emphasize a multidisciplinary approach to finding and treating MTrPs and making sure urological, gynecological, and/or colorectal pathologies are addressed. A thorough subjective and physical exam that leads to proper diagnosis of MTrPs should be followed by manual physical therapy techniques and appropriate medical intervention for any corresponding pathology.

Halder et al. (2017) investigated the efficacy of myofascial release physical therapy with the addition of Botox in a retrospective case series for women with myofascial pelvic pain. Fifty of the 160 women who had Botox and physical therapy met the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the primary complaint in all those subjects was dyspareunia. The Botox was administered under general anesthesia, and then the same physician performed soft tissue myofascial release transvaginally for 10-15 minutes, with 10-15 additional minutes performed if rectus muscles had trigger points. The patients were seen 2 weeks and 8 weeks posttreatment. Average pelvic pain scores decreased significantly pre- and posttreatment, with 58% of subjects reporting improvements. Significantly fewer patients (44% versus 100%) presented with trigger points on pelvic exam after the treatment. The patients who did not show improvement tended to have inflammatory or irritable bowel diseases or diverticulosis. Blocking acetylcholine receptors via Botox in combination with pelvic floor physical therapy could possibly provide longer symptom-free periods. Although the nature of the study could not determine a specific interval of relief, the authors were encouraged as an average of 15 months passed before 5 of the patients sought more treatment.

The need for the specific treatment for myofascial pelvic pain is determined by a clinician competent in palpation of the pelvic floor musculature finding trigger points and restrictions in the tissue. Listening to a patient’s symptoms and understanding pelvic pathology allow for better treatment planning. Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist is a comprehensive course to enhance knowledge in your head to lead your hands in the right direction for assessing/treating patients with pelvic pain.

Pastore, E. A., & Katzman, W. B. (2012). Recognizing Myofascial Pelvic Pain in the Female Patient with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing : JOGNN / NAACOG, 41(5), 680–691. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01404.x

Halder, G. E., Scott, L., Wyman, A., Mora, N., Miladinovic, B., Bassaly, R., & Hoyte, L. (2017). Botox combined with myofascial release physical therapy as a treatment for myofascial pelvic pain. Investigative and Clinical Urology, 58(2), 134–139. http://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2017.58.2.134

My manual therapist husband once wrote a paper on the visceral referral pattern of the liver. Although he knows I injured my right shoulder shoveling snow a few years ago, whenever I have an exacerbation of shoulder pain, he likes to joke it is from my liver. (I would laugh if I had not acquired an affinity for red wine since having kids!) Sometimes pain in remote areas of our body really can be related to an organ in distress or simply “stuck” because of fascial restrictions around it. The kidneys in particular can refer pain into the low back and hips, and the bladder and ureters can provoke saddle area pain.

Tozzi, Bongiorno, and Vitturini (2012) looked into the kidney mobility of patients with low back pain. They used real-time Ultrasound to assess renal mobility before and after osteopathic fascial manipulation (OFM) via the Still Technique and Fascial Unwinding. The experimental group receiving OFM consisted of 109 people, and the control group receiving a sham treatment had 31 people, all with non-specific low back pain. For comparison, 101 subjects without back pain were also assessed with the ultrasound to determine a mean Kidney Mobility Score (KMS). The landmarks for measuring the renal mobility were the superior renal pole of the right kidney and the pillar of the right diaphragm, and they subtracted the distance at maximal inspiration (RdI) from that of maximal expiration (RdE). A significant difference was found in the KMS scores of asymptomatic versus symptomatic subjects with low back pain. Pre and post-RD values of the experimental group were significantly different from the control group. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire also demonstrated significant differences in the experimental versus control groups. The results of the study revealed a correlation between decreased renal mobility and non-specific low back pain and showed an improvement in renal mobility and low back pain after an osteopathic manipulation.

In 2016, Navot and Kalichman presented a case study of a 32 year old professional male cyclist with right hip and groin pain after an accident that caused a severe hip contusion and tearing of the tensor fascia latae and the gluteus medius muscles. A few rounds of physical therapy gave him partial relief of his pain in sitting and with cycling, and his hip range of motion only improved slightly. Despite no complaints of pelvic floor dysfunction, he was evaluated for involvement of the pelvic floor musculature and fascia. Pelvic Floor Fascial Mobilization was performed for 2 sessions, and the cyclist’s symptoms resolved completely. This case implied the efficacy of manual fascial release of the pelvic floor to reduce hip and groin pain.

When something seemingly orthopedic in nature does not respond with full resolution of symptoms from traditional physical therapy, the source of the pain may be deeper. Often times, we just need to ask the right questions to uncork the mystery of why a pain is lingering. No matter how skilled we are with our techniques, if we are not reaching the area in need, we are wasting our effort and our patients’ time and money. “Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System” is a course that provides a practitioner with the extra insight and tools to address potential sources of unresolved symptoms of low back, hip, and groin pain.

Tozzi, P., Bongiorno, D., and Vitturini, C. (2012) Low back pain and kidney mobility: local osteopathic fascial manipulation decreases pain perception and improves renal mobility. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 16(3):381-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.02.001

Navot, S and Kalichman, L. (2016). Hip and groin pain in a cyclist resolved after performing a pelvic floor fascial mobilization. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 20(3):604-9. doi:10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.04.005

Myofascial release (MFR) can be one of your greatest treatment tools as a pelvic rehabilitation practitioner. Just in case you don’t think about fascia often here are a couple helpful things to remember. Fascia is the irregular connective tissue that covers the entire body, and it is the largest sensory system in the body, making it highly innervated. The mobilizing effect of MFR techniques occurs by stimulating various mechanoreceptors within the fascia (not by the actual force applied). MFR techniques can help to reduce tissue tension, relax hypertonic muscles, decrease pain, reduce localized edema, and improve circulation just to name a few physiological effects.

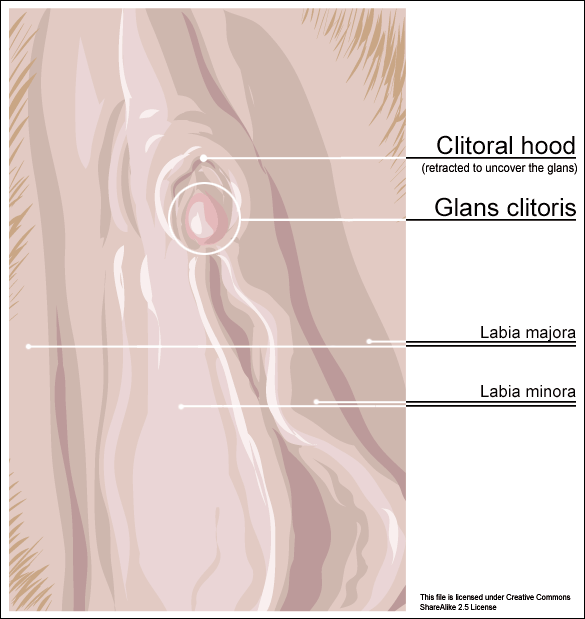

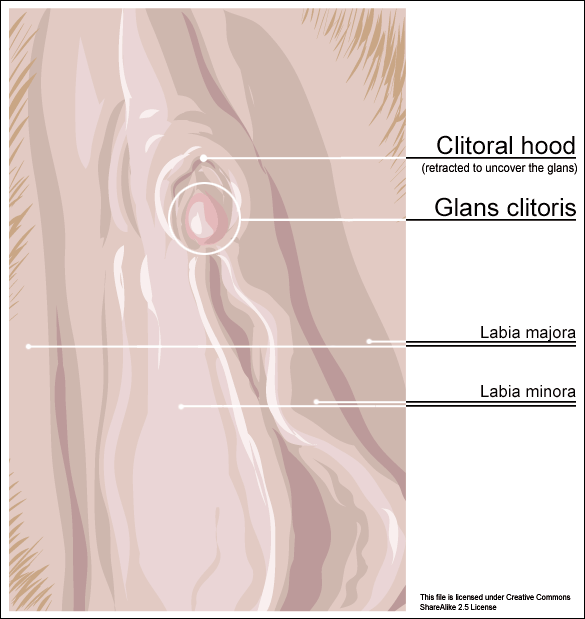

An interesting case report published in 2015 by the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1 offers a wonderful example of how a physical therapist used specific MFR techniques for a patient with clitoral phimosis and dyspareunia. The specific MFR techniques used helped to provide relief and restore mobility to the pelvic tissues for this patient.

An interesting case report published in 2015 by the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy1 offers a wonderful example of how a physical therapist used specific MFR techniques for a patient with clitoral phimosis and dyspareunia. The specific MFR techniques used helped to provide relief and restore mobility to the pelvic tissues for this patient.

Clitoral phimosis is adherence between the clitoral prepuce (also known as the clitoral hood) and the glans. This condition can be the result of blunt trauma, chronic infection, inflammatory dermatoses, and poor hygiene. In this case report, the 41-year-old female patient had sustained a blunt trauma injury to the vulva (when her toddler son charged, contacting his head forcibly into her pubic region). She presented to physical therapy with complaints of dyspareunia, low back pain, a bruised sensation of her pubic region, vulvar pain provoked by sexual arousal, decreased clitoral sensitivity, and anorgasmia. The physical therapist completed an orthopedic assessment for the lower quarter (including spine and extremities), as well as a thorough pelvic floor muscle assessment.

Treatment for this patient addressed not only the pelvic complaints, but the lower quarter complaints as well. A detailed treatment summary for each visit is outlined in the case report. The clitoral MFR and stretching was performed by applying a small amount of topical lubricant to the clitoral prepuce. Then, a gloved finger or a cotton swab was used to stabilize the clitoris, a prolonged MFR or sustained stretch was applied in the direction away from the fixated clitoris by the therapist’s other finger. The therapist applied this technique along the entire length of the prepuce. The other physical therapy interventions this patient was treated with were stretching, joint mobilization, muscle energy techniques, transvaginal pelvic floor muscle massage, clitoral prepuce MFR techniques, biofeedback, Integrative Manual Therapy (IMT) techniques, nerve mobilization, and therapeutic and motor control exercises. Additionally, between the physical therapy evaluation and the second visit the patient did use topical Clobetasol 0.05% cream (commonly prescribed for vulvar dermatitis issues such as Lichen Sclerosis) for 30 days with no change to her clitoral phimosis.

After 11 sessions, the patient had resolution of dyspareunia, vulvar pain, pubic pain, and reduced low back pain. Also, the patient had 100% restored mobility of the clitoral prepuce, as well as normalized clitoral sensitivity and clitoral orgasm. The patient felt these improvements were still present at her 6-month follow-up interview over the phone. Current medical management for clitoral phimosis is surgical release or topical/injectable corticosteroids. Having a conservative treatment option, such as MFR, for this condition can be helpful for patients. As with most evolving treatment techniques, more research and studies are appropriate.

Not one health care professional had ever assessed the fascial mobility of the clitoris until this physical therapist did. This case report is an example of how MFR techniques can be effective treatment tools for your patients with pelvic disorders and a good reminder to check the fascial mobility of the pelvic tissues.

Morrison, P., Spadt, S. K., & Goldstein, A. (2015). The Use of Specific Myofascial Release Techniques by a Physical Therapist to Treat Clitoral Phimosis and Dyspareunia. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 39(1), 17-28.

“…visceral manual therapy can produce immediate hypoalgesia in somatic structures segmentally related to the organ being mobilized…”

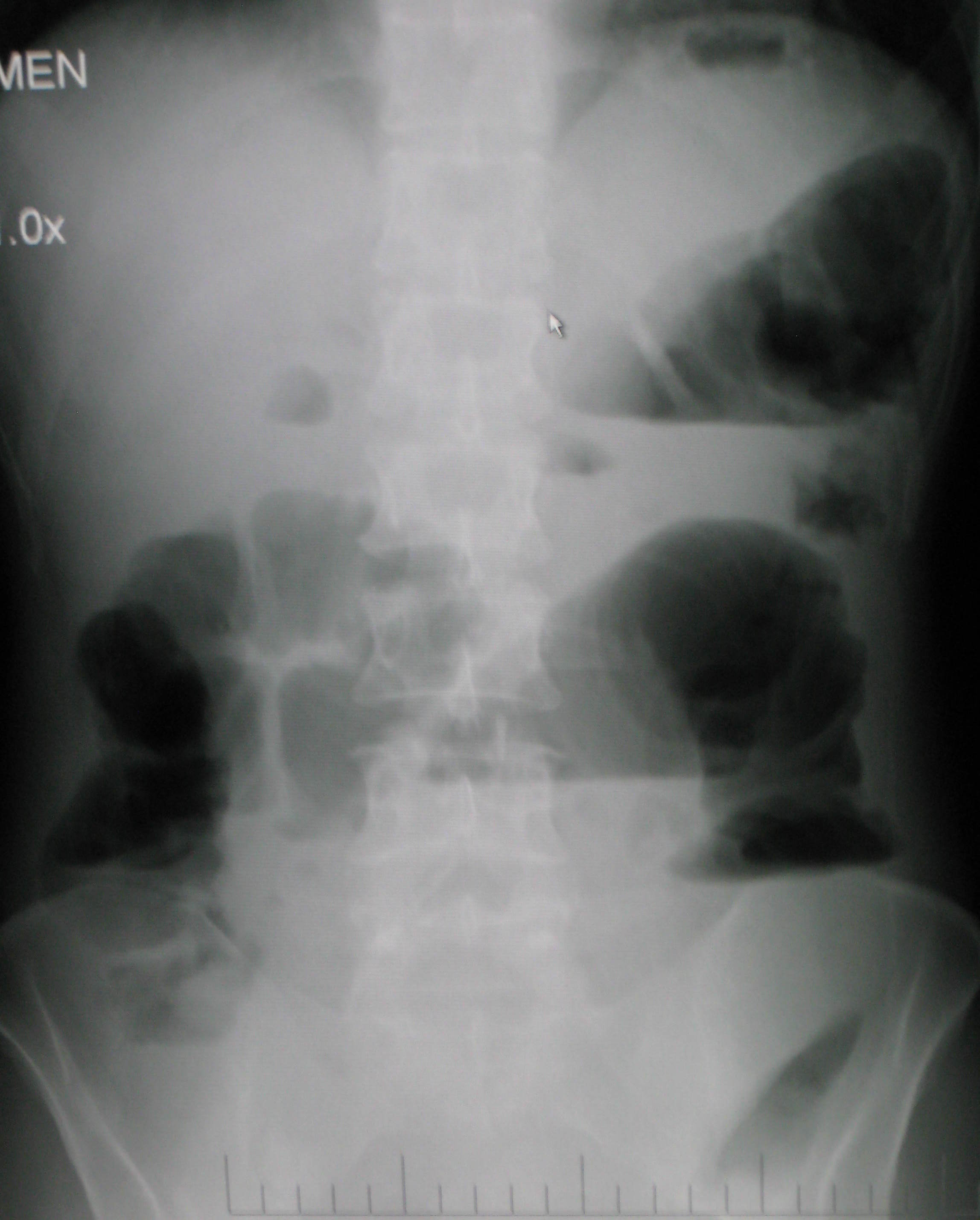

This statement is taken from an article written by MCSweeney and colleagues published in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies in 2012. The authors, who state that there is a lack of research that explains underlying mechanisms for visceral mobilization, aimed to determine if visceral mobilization could produce local and/or systemic effects towards hypoalgesia. The measurement of hypoalgesia, defined by the IASP as “diminished pain in response to a normally painful stimulus,” was assessed by use of a hand-held manual digital pressure algometer for pressure pain threshold (PPT). Sixteen asymptomatic subjects were recruited from an osteopathic school and were treated on separate occasions with a visceral mobilization of the sigmoid colon, a sham intervention of manual contact on the abdomen, and a control of no intervention. Six females (mean age 23.7) and ten males (mean age 27.7) completed the single-blinded, randomized study.

The clinical practice relevance was difficult to determine, however, this study used new techniques to determine that there is an immediate and measurable effect on the body. While therapists who treat with visceral mobilization and other soft tissue techniques know that the interventions have helped their patients, having further experimental and clinical validation of the value of these techniques is critical. If you are interested in learning more about fascial approaches to easing pain and improving function in your patients, check out the courses offered by faculty member Ramona Horton.

Ramona will be teaching her Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremities course three times this year, with the next event in Nashua, NH June 3-5. Her Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System course is available three times as well, next in Kirkland, WA on June 24-26. If you're ready for the advanced course, and some wine tasting(!), check out Mobilization of Visceral Fascia: The Reproductive System of Men and Women on October 14-16 in Medford, OR.

McSweeney, T. P., Thomson, O. P., & Johnston, R. (2012). The immediate effects of sigmoid colon manipulation on pressure pain thresholds in the lumbar spine. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies, 16(4), 416-423.

If an infomercial played in pre-op waiting rooms explaining all the possible side effects or problems a patient may encounter after surgery, I wonder how many people would abort their scheduled mission. As if having an abdominal or pelvic surgery were not enough for a patient to handle, some unfortunate folks wind up with small bowel obstruction as a consequence of scar tissue forming after the procedure. Instead of having yet another surgery to get rid of the obstruction, which, in turn, could cause more scar tissue issues, studies are showing manual therapy, including visceral manipulation, to be effective in treating adhesion-induced small bowel obstruction.

Amanda Rice and colleagues published a paper in 2013 on the non-surgical, manual therapy approach to resolve small bowel obstruction (SBO) caused by adhesions as evidenced in two case reports. One patient was a 69 year old male who had 3 hernia repairs and a laparotomy for SBO with resultant abdominal scarring and 10/10 pain on the visual analog scale. The other patient was a 49 year old female who endured 7 abdominopelvic surgeries for various issues over the course of 30 months and presented with 7/10 pain and did not want more surgical intervention for SBO. Both patients received 20 hours of intensive manual physical therapy over a period of 5 days. The primary focus was to reduce adhesions in the bowel and abdominal wall for improved visceral mobility, but treatment also addressed range of motion, flexibility, and postural strength. The female patient reported 90% improvement in symptoms, with significant decreases in pain during bowel movements or sexual intercourse, and the therapist noted increased visceral and myofascial mobility. Both patients were able to avoid further abdominopelvic surgery for SBO, and both patients were still doing well at a one year follow up.

Amanda Rice and colleagues published a paper in 2013 on the non-surgical, manual therapy approach to resolve small bowel obstruction (SBO) caused by adhesions as evidenced in two case reports. One patient was a 69 year old male who had 3 hernia repairs and a laparotomy for SBO with resultant abdominal scarring and 10/10 pain on the visual analog scale. The other patient was a 49 year old female who endured 7 abdominopelvic surgeries for various issues over the course of 30 months and presented with 7/10 pain and did not want more surgical intervention for SBO. Both patients received 20 hours of intensive manual physical therapy over a period of 5 days. The primary focus was to reduce adhesions in the bowel and abdominal wall for improved visceral mobility, but treatment also addressed range of motion, flexibility, and postural strength. The female patient reported 90% improvement in symptoms, with significant decreases in pain during bowel movements or sexual intercourse, and the therapist noted increased visceral and myofascial mobility. Both patients were able to avoid further abdominopelvic surgery for SBO, and both patients were still doing well at a one year follow up.

In 2016, a prospective, controlled survey based study by Rice et al., determined the efficacy of treating SBO with a manual therapy approach referred to as Clear Passage Approach (CPA). The 27 subjects enrolled in the study received this manual therapy treatment for 4 hours, 5 days per week. The CPA includes techniques to increase tissue and organ mobility and release adhesions. The therapist applied varying degrees of pressure across adhered bands of tissue, including myofascial release, the Wurn Technique for interstitial spaces, and visceral manipulation. The force used and the time spent on each area were based on patient tolerance. The SBO Questionnaire considered 6 domains (diet, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, medication, quality of life, and pain severity) and was completed by 26 of the subjects pre-treatment and 90 days after treatment. The results revealed significant improvements in pain severity, overall pain, and quality of life. Suggestive improvements were noted in gastrointestinal symptoms as well as tissue and organ mobility via improvement in trunk extension, rotation, and side bending after treatment. Overall, the authors conclude the manual therapy treatment of SBO is a safe and effective non-invasive approach to use, even for the pediatric population with SBO.

Myofascial release and visceral manipulation can disrupt the vicious cycle of adhesions causing small bowel obstruction after abdominopelvic surgical “invasion.” Learning specific techniques we may never have thought of can make a huge impact on certain patient populations. Quality of life for our patients often depends on how willing we are to increase our own knowledge and skill base.

Rice, A. D., King, R., Reed, E. D., Patterson, K., Wurn, B. F., & Wurn, L. J. (2013). Manual Physical Therapy for Non-Surgical Treatment of Adhesion-Related Small Bowel Obstructions: Two Case Reports . Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2(1), 1–12. PubMed Link

Rice, A. D., Patterson, K., Reed, E. D., Wurn, B. F., Klingenberg, B., King, C. R., & Wurn, L. J. (2016). Treating Small Bowel Obstruction with a Manual Physical Therapy: A Prospective Efficacy Study. BioMed Research International, 2016, 7610387. http://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7610387

Today we get to hear from Ramona Horton, MPT, who teaches several courses with the Herman & Wallace Institute. Her upcoming course, Visceral Mobilization Level 1: Mobilization of Visceral Fascia for the Treatment of Pelvic Dysfunction in the Urologic System, will be taking place November 6-8, 2015 in Salt Lake City, UT.

This spring I reached a milestone in my career. I have been working as a licensed physical therapist for 30 years, of which the past 22 have been in the field of pelvic dysfunction. Other than some waitressing stents and a job tending bar while in college this is the only profession I have known. When I entered the US Army-Baylor program in Physical Therapy in the fall of 1983 nowhere was it on my radar screen that I would be dealing with the nether regions of men, women and children, let alone teaching others to do so. As time marches on, I find myself visiting my hair dresser a bit more frequently to deal with that ever progressive grey hair that marks the passage of these years…translation: I am an old dog and I have been forced to learn some new tricks.

This spring I reached a milestone in my career. I have been working as a licensed physical therapist for 30 years, of which the past 22 have been in the field of pelvic dysfunction. Other than some waitressing stents and a job tending bar while in college this is the only profession I have known. When I entered the US Army-Baylor program in Physical Therapy in the fall of 1983 nowhere was it on my radar screen that I would be dealing with the nether regions of men, women and children, let alone teaching others to do so. As time marches on, I find myself visiting my hair dresser a bit more frequently to deal with that ever progressive grey hair that marks the passage of these years…translation: I am an old dog and I have been forced to learn some new tricks.

Like many aspects of our modern life, the profession of physical therapy is under a constant state of evolution. The best example of this is the way we look at pain and physical dysfunction. I was educated under the Cartesian model, one that believed pain is a response to tissue damage. Through quality research and better understanding of neuroscience we now know that this simplistic model is, in a word, too simple. We have come to recognize that pain is an output from the brain, which is acting as an early warning system in response to a threat real or perceived. I wholeheartedly embrace the concept that pain is a biopsychosocial phenomenon; however I am not willing to give up my treatment table for a counselors couch when dealing with persistent pain patients.

As a physical therapist, I still believe that we need to educate, strengthen and yes, touch our patients. Given that paradigm, ultimately I am a musculoskeletal therapist and I believe that when a clinician is designing a treatment program for any patient, applying sound clinical reasoning skills means the clinician needs to take into consideration that there are three primary areas in the individuals life in which they may be encountering a barrier to optimal function: neuro-motor, somatic and psycho-social. After many years of developing and refining my clinical reasoning model, I have chosen to adopt the image of the Penrose triangle. My goal was to provide the clinician with a visual on which to focus their problem solving skills and a reminder to encompass the person as a whole. The goal is to convey the understanding that the barriers which present themselves rarely do so in isolation, and that the source to resolve of all barriers that impede human function, regardless of origin, is ultimately found within the brain.

Neuro-motor barriers include issues of muscle function to include motor strength, length, endurance, timing and coordination. These barriers are improved through therapeutic exercise training. Somatic barriers are those that are addressed through any number of manual therapy interventions which address issues found within multiple structures to include the fascia, osseous/articular tissue, lymphatic congestion, restrictions within the visceral connective tissue, neural/dural restrictions and challenges of the dermal/integumentary system. All of these barriers can contribute to nociceptive afferent activity. Lastly would be the psychosocial barriers which include history of trauma, clear behavior of hypervigilance, catastrophization, current life stressors, perceived threat which includes kinesiophobia (back to neuro-motor) ANS issues which present as autonomic dysregulation and lastly pain model misconceptions.

I suggest that we remember that the body is a self-righting mechanism. If we cut our skin, given the wound is kept free from infection (a barrier), the human body will heal the wound. As clinicians, I believe that we need to come to the realization that we don’t fix anything, we simply remove the barrier to healing and trust the body to do the rest. Our challenge is to recognize and address the barriers.