Several weeks ago, I evaluated a patient who was referred to me from a fellow physical therapist. The patient was suffering from sacroiliac joint and low back pain. The patient is a 34-year-old nulliparous woman who is physically fit and participates in several outdoor activities. The therapist had fully evaluated the patient and did not find any articular issues within her spine or pelvis. What she did find was weakness in her local stabilizing muscles and tightness in her global stabilizing muscles. The therapist has an ample amount of clinical experience at treating low back and pelvic pain issues. She is adept at using different verbal cues, positions, and tactile cueing in order to help encourage proper activation of the local core muscles. However, the therapist knew the patient was not getting her local core muscles to fire properly. She didn’t know what else to do with this patient in order to get her to properly activate these muscles. She had tried numerous positions, verbal and tactile cueing without success.

Several weeks ago, I evaluated a patient who was referred to me from a fellow physical therapist. The patient was suffering from sacroiliac joint and low back pain. The patient is a 34-year-old nulliparous woman who is physically fit and participates in several outdoor activities. The therapist had fully evaluated the patient and did not find any articular issues within her spine or pelvis. What she did find was weakness in her local stabilizing muscles and tightness in her global stabilizing muscles. The therapist has an ample amount of clinical experience at treating low back and pelvic pain issues. She is adept at using different verbal cues, positions, and tactile cueing in order to help encourage proper activation of the local core muscles. However, the therapist knew the patient was not getting her local core muscles to fire properly. She didn’t know what else to do with this patient in order to get her to properly activate these muscles. She had tried numerous positions, verbal and tactile cueing without success.

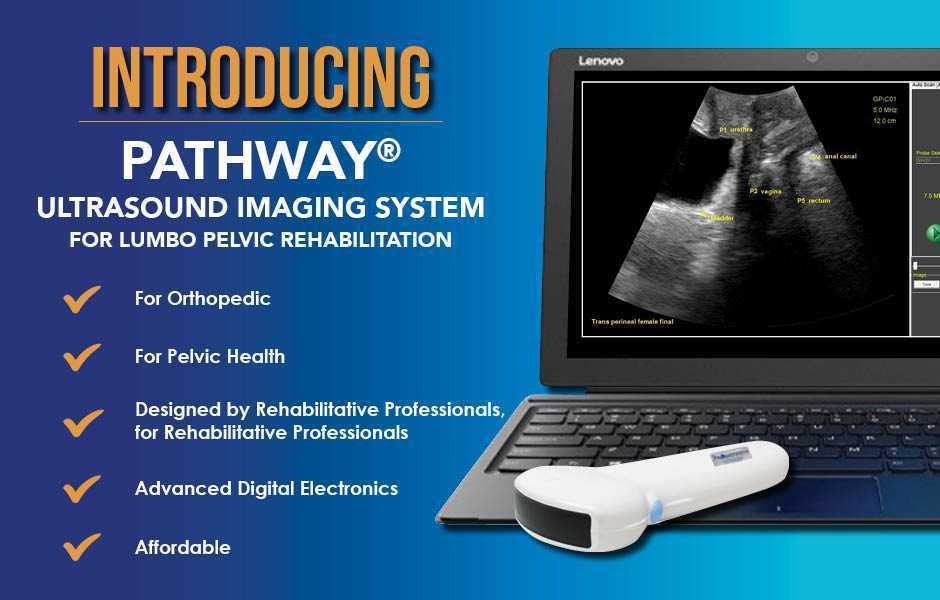

Do you ever have patients where you feel stuck, who are not progressing as you would like them to in treatment? We all do! It is frustrating, isn’t it? The physical therapist called me and asked me to evaluate the patient using real-time ultrasound imaging. The therapist said “If the patient can just see what she is doing, she will then be able to learn how to work the muscles correctly.” She referred the patient to me so I could use ultrasound imaging within the treatment to better assess her activation strategies and use the imaging for biofeedback for with the patient. The patient was amazed with the ability to see what the different layers of muscles were doing. We found she was contracting her TA but only on her left side, and her deep multifidus was not firing at all. Using the ultrasound images, the patient was able to learn the proper way to activate her muscles. She is now working on a strengthening program for her local core muscles including her TA, pelvic floor, and multifidus. Within two treatments, the patient was able to fire her muscles in a different way and reports her back has felt better than it has in years!

The Pathway Ultrasound Imaging System, available from The Prometheus Group, is a portable ultrasound solution for pelvic rehab

I cannot emphasize enough how using ultrasound might change your practice! It not only can help you when you are stuck with a patient’s progress, but it can attract more patients to your practice. There are a lot of visual learners out there and access to visual images in therapy can influence progress and the results that are achieved. You not only can use the ultrasound to retrain the local core muscles for back and pelvic instability patients, but you can use it for incontinence patients, prolapse patients, and post prostatectomy patients as well. You can strengthen the pelvic floor without having to disrobe the patient each visit. How many men and women would appreciate that?

If you are interested in learning more about how you can use ultrasound in your practice, join me in August in New Jersey, or in November in California for Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging - Women's Health and Orthopedic Topics! See you there!

I’m Elizabeth Hampton PT, DPT, WCS, BCB-PMD and I teach “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain”, which offers practitioners a systematic screening approach to rule in or rule out contributing factors to pelvic pain. This course helps clinicians to understand and screen for the common co-morbidities associated with pelvic floor dysfunction, like labral tears, discogenic low back pain, nerve entrapments, coccygeal dysfunction, and more. Importantly, it also coaches clinicians to organize information in a way that enables them to prioritize interventions in complex cases. I've noticed that there are some questions that course participants frequently have as they talk through common themes in their care challenges and wrote this blog to share some clinical pearls you may find to be helpful for your own practice or as an explanation to your clients.

Here are some of the most common questions that I get when teaching Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain:

1) Question: How do I even start to organize information when a client has a complex history and I am feeling overwhelmed?

I write down a road map with key categories: Bowel and bladder; Spine; Sacroiliac Joint/Pubic Symphysis; Hip; Pelvic floor muscles; biomechanics; respiration; neural upregulation; whatever details can be fit into ‘big buckets’ of information. I use it to both organize my thoughts for my notes, as well as educate the client as to what my findings are and the design of their treatment program.

2) Question: How do you get your clients to do a bowel and bladder diary?

I am proud to say that I can talk anyone into a 7 day bowel and bladder diary because I tell them how incredibly helpful it is to understand the way their body responds to what they eat, drink, and daily habits. It’s my secret weapon to snag clients to start connecting with their body and listening to their details, educate about defecation ergonomics and what happens in multiple systems when there is pelvic floor overactivity. It’s a great teaching tool that facilitates self-reflection and how their self-care choices impact their body’s behavior.

3) Question: How do you educate clients about pelvic floor function so they don’t focus so much on Kegels?

Pelvic floor muscles do three things:

-

They contract gently, or powerfully, with no discomfort, and totally normal breathing; PFMs should have the same kind of nuanced control like your voice does: they should be able to do a gentle contraction, like a “whisper” or a powerful contraction, like a “shout”, depending on the task position and intent.

-

They relax fully and completely when the body is resting in support, or they should be able to relax to a supportive level when they are needed posturally. Relaxation should be its own celebrated event!

-

They should be able to relax and gently lengthen.

Faculty member Elizabeth Hampton PT, DPT, WCS, BCB-PMD is the author and instructor of Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain, a course designed to help practitioners utilize differential diagnosis in evaluating pain. Join Dr. Hampton in Portland, OR on July 27-29, 2018 or November 2-4, 2018 in Phoenix, AZ.

Recently, I had a patient present to my practice with unretractable vaginal pain that was causing her quite a bit of suffering. Peyton (name changed) had been referred by a local osteopathic physician. For around a year, she had increasing severe vaginal pain. There was no history of assault, trauma, fall, or injury around the time of onset of symptoms. However, she had a kidney infection that caused back pain in the month prior to her pain onset.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

Peyton is home schooled, but she was unable to attend outings that required longer sitting, such as field trips or church. She also was having some urinary retention with start and stop stream and resultant urinary frequency. Peyton’s mother said the pain was distressing to Peyton and would cause her to cry. She had an unremarkable medical history. However, under further questioning, we discovered she did have a history of bed wetting later than usual (until age 7) and she had persistent leg pain. With standing longer than 15 minutes, her legs would hurt and feel weak, which prevented her from performing sports or being physically active. She also had experienced some achy low back sensations since the kidney infection. Peyton had been screened by urology, her primary care, an osteopath, as well as a vulvar pains specialist who diagnosed her with nerve pain, but said there is no good viable treatment.

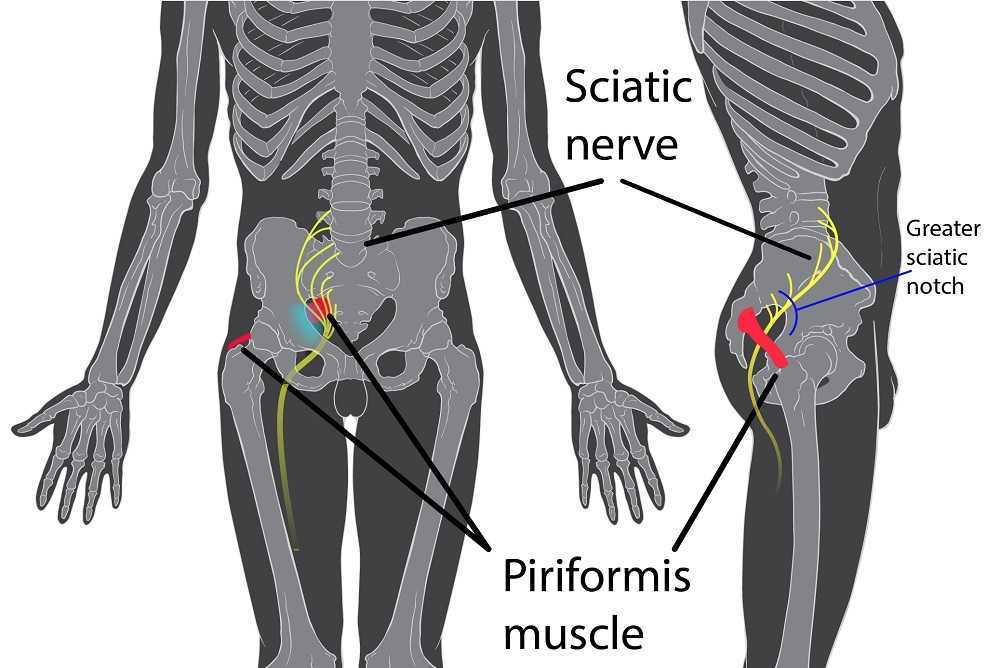

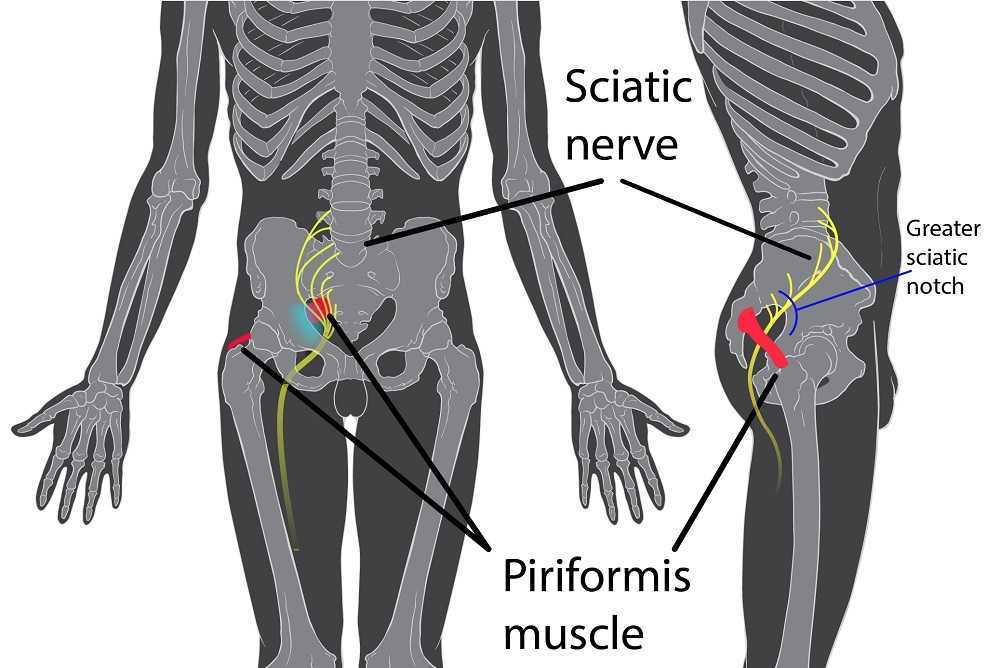

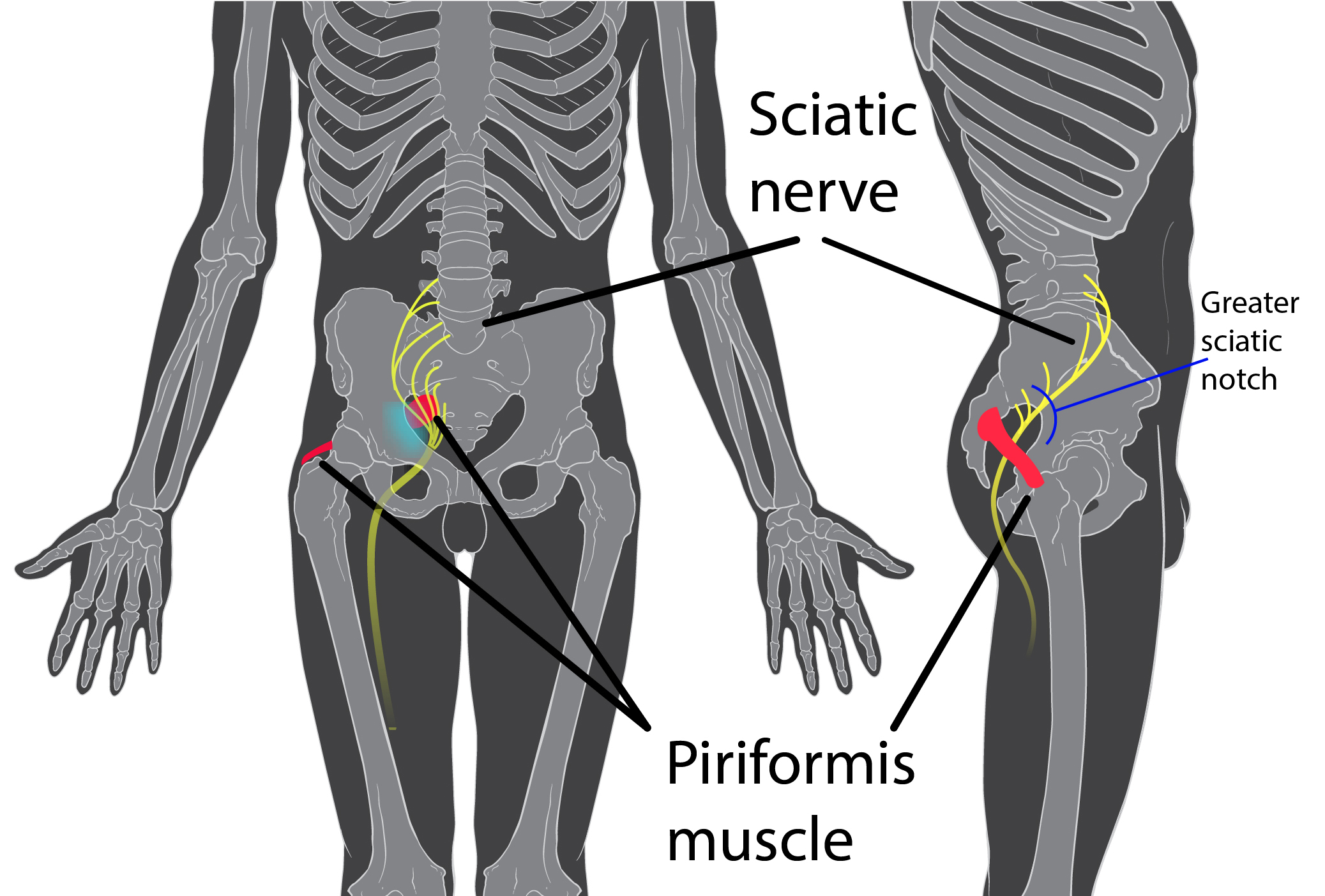

Objective findings revealed normal range of motion in her spine with the exception of limited forward flexion (feeling of back tightness at end range). Hip screening was negative for FABERS, labral screening or capsular pain patterns. General dural tension screening was positive for increased lower extremity and sensation of back tightness with slump c sit. Neural tension test was positive bilaterally for sciatic, R genitofemoral, L Iliohypogastric and Ilioinguinal nerves, and bilateral femoral nerves. Patient had a mild, barely perceptible lumbar scoliosis, and development of bilateral lower extremities and feet was symmetric and normal.

Because of the child’s age, we did not perform internal vaginal exam or treatment. This required treating the nerves that supply the vaginal area. All treatments were done with the patient’s mother present with both consent of the child and the mother.

For treatment, we started with the three inguinal nerves (Ilioinguinal, Iliohypogastric and genitofemoral) because of their relationship with the kidney (symptoms came on after kidney infection) as well as the correlation with the patient’s most limiting symptoms (genital pain). We cleared the fascia along the lumbar nerve roots, the lateral trunk fascia, the psoas, the inguinal region, the entrapments along the kidney and psoas, the inguinal rings and canal, and worked on neural rhythm (these techniques can be learned at the Pelvic Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment class that I will be teaching later this month).

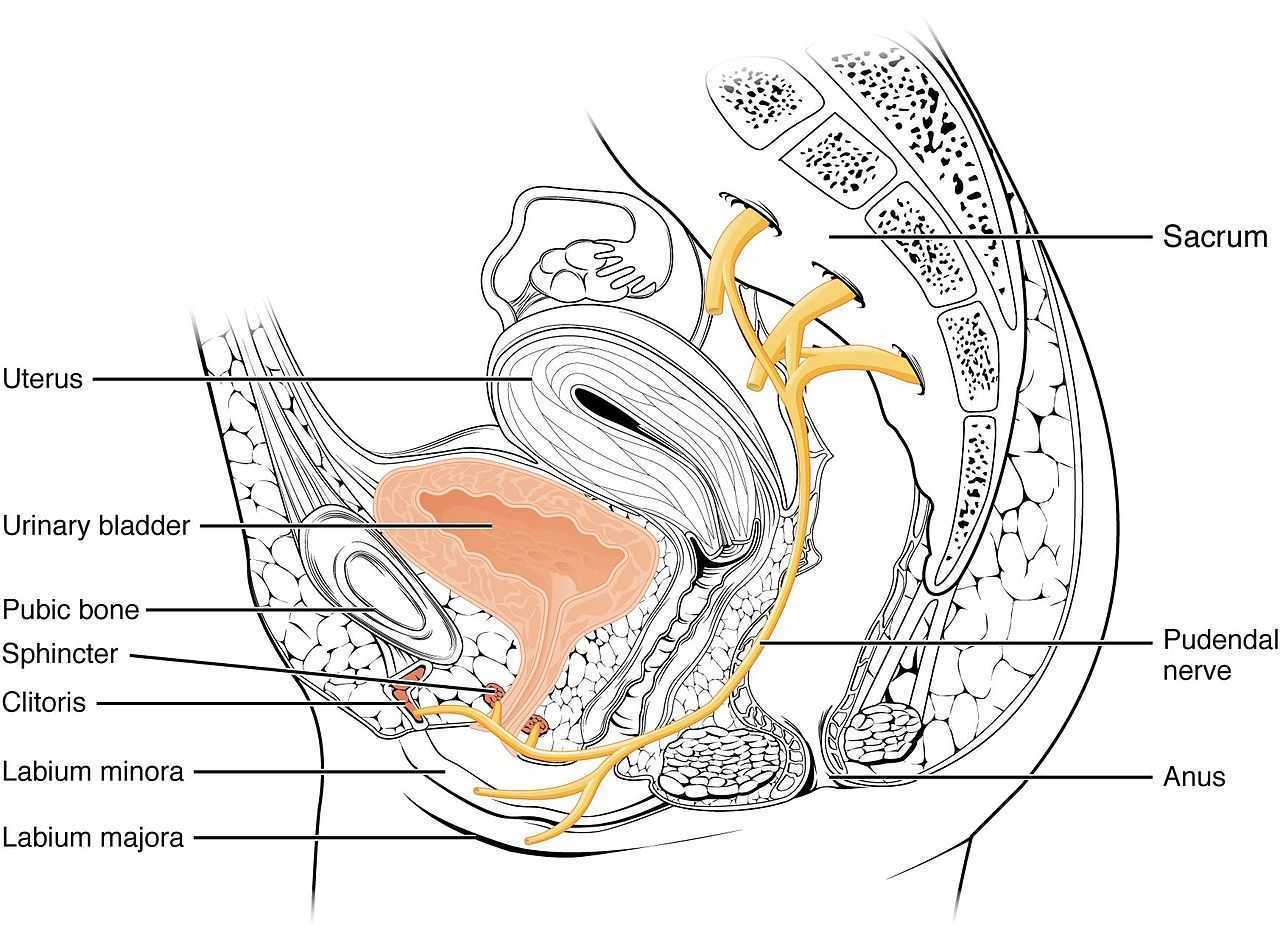

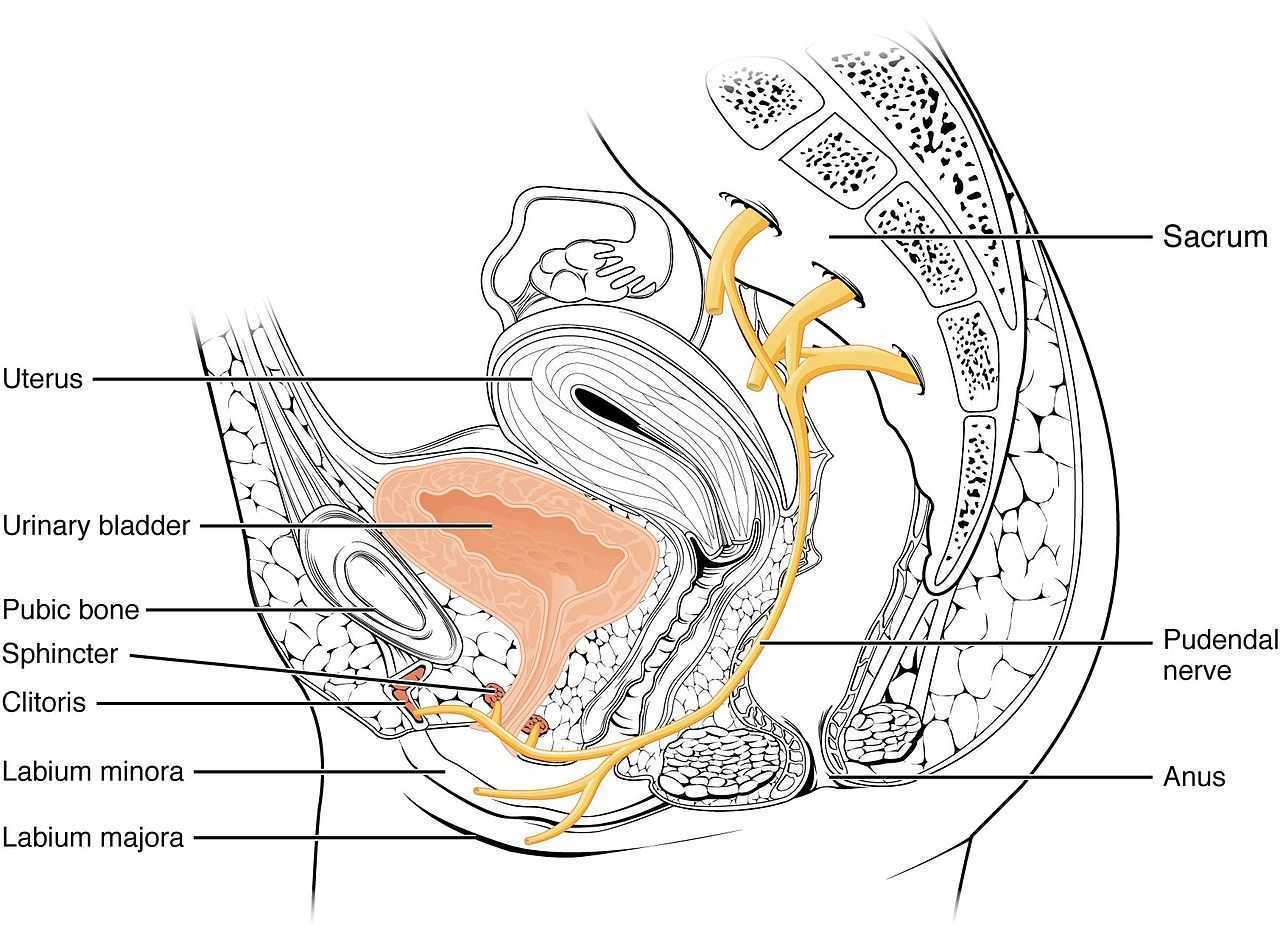

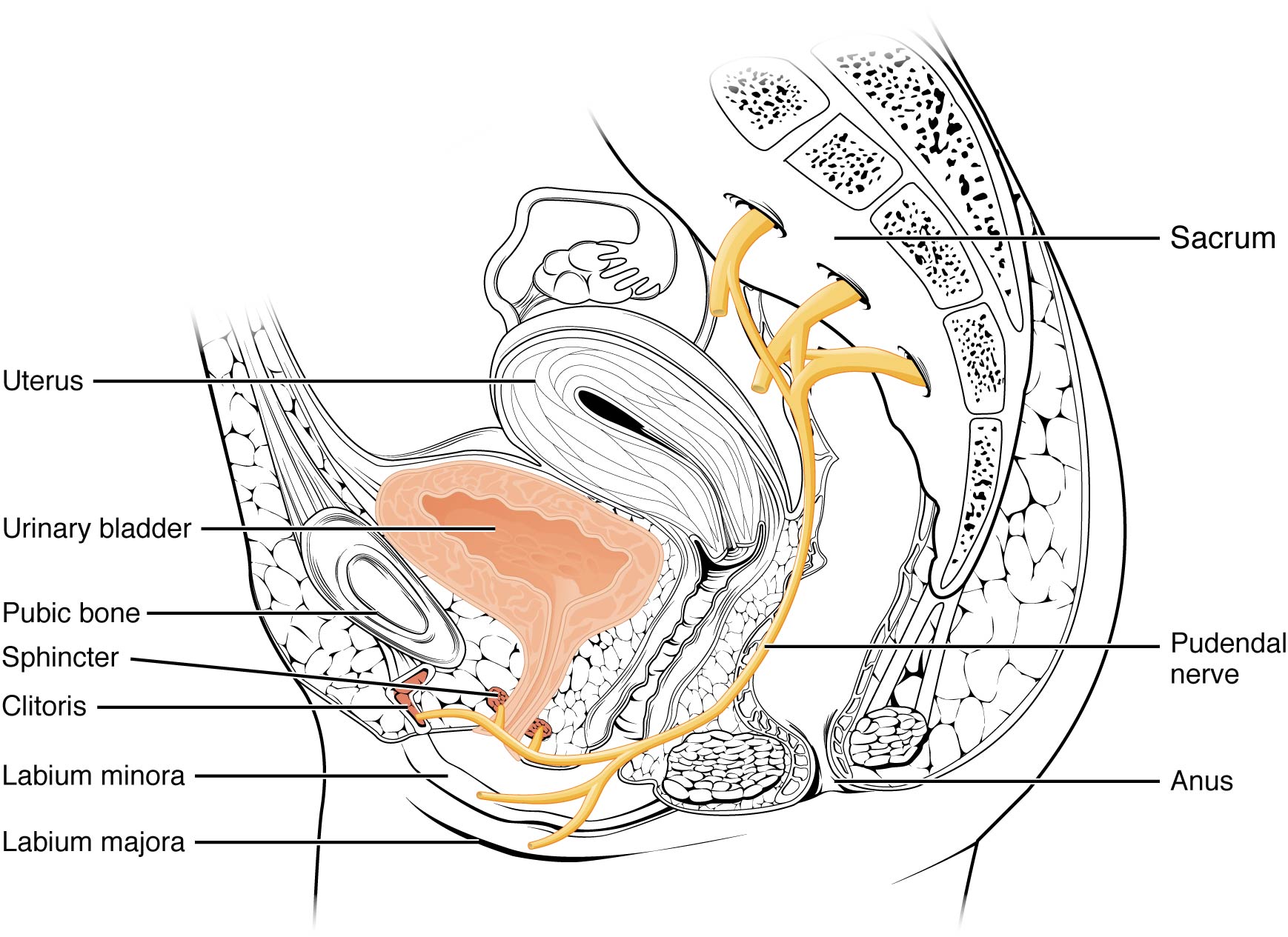

Over the next weeks, we used similar treatments for the sciatic nerve, femoral nerve, pudendal, and coccygeal nerves. We noted that the patient had an area of restricted tissue along her coccyx that was adhered, and her symptoms had some correlation with tethered cord. We did lots of soft tissue work along the coccyx and working along the coccyx roots, including some internal rectal work. We also did fascial and visceral work in the bladder region, as well as in the lumbar and sacro-coccygeal region.

Peyton’s referring physician and mother were notified of findings and possible tethered cord symptoms (leg weakness and pain, bladder symptoms, delayed nocturnal continence). The patient’s family felt she was getting better and was not interested in any kind of surgical intervention, and her physician also felt that with our progress, he was not interested in exploring that referral, unless the family was interested.

After just 4 treatments Peyton was no longer having any vaginal symptoms and was emptying the bladder normally. After 8 treatments Peyton was reporting no more lumbar pain or lower extremity symptoms, and follow up treatments were reduced to once a month. The patient was given a home program of neural flossing in a small yoga program we recorded on her mother’s phone. We had her mother work on the small area that remained adhered along patient’s tailbone. The area is much smaller, but it reproduces some pelvic pain for the patient, so we are carefully and slowly working along this area because of some of the global neural sx it produces.

The patient’s mother reports she is more active, no longer complaining of leg or vaginal pain. The patient has less generalized anxiety and she is able to void fully. When the pt grows in height, there is a return in some symptoms, likely due to increased neural tension. So, we have the family on standby and when the patient grows, they come back in for 2 visits, which is usually enough to get the patient back to her new baseline.

My 6 year old girl (going on 13) asks “Alexa” to play the Descendants II soundtrack over and over again. So the song, “Space Between,” was lingering in my head while reading the most recent articles on pudendal neuralgia, particularly when pudendal entrapment is to blame. After all, entrapment, by medical standards, describes a peripheral nerve basically being caught in between two surrounding anatomical structures.

Ploteau et al., (2016) presented 2 case studies highlighting the warning signs when pudendal nerve entrapment does not follow the Nantes criteria. A brief summary of those 5 criteria follows:

Ploteau et al., (2016) presented 2 case studies highlighting the warning signs when pudendal nerve entrapment does not follow the Nantes criteria. A brief summary of those 5 criteria follows:

- Pain in the region of the pudendal nerve innervation from anus to penis or clitoris.

- Pain most predominant while sitting.

- The patient does not wake at night from the pain.

- No sensory impairment can be objectively identified.

- Diagnostic pudendal nerve block relieves the pain.

The case studies of a 31 and a 68 year old female revealed endometrial stromal sarcoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma in the ischiorectal fossa, with night pain was noted in both patients, as well as no pain with sitting or defecation, respectively. Clinicians must always be mindful to resolve red flags in patients.

In 2016, Florian-Rodriguez, et al., studied cadavers to determine the nerves associated with the sacrospinous ligament, focusing on the inferior gluteal nerve. Fourteen cadavers were observed, noting the distance from various nerves to the sacrospinous ligament (from a pelvic approach) and to the ischial spine (from a gluteal approach). The S3 nerve was closest to the sacrospinous ligament, and the pudendal nerve was the closest to the ischial spine. In 85% of subjects, 1 to 3 branches from S3/S4 nerves pierced or ran anterior to the sacrotuberous ligament and pierced the inferior part of the gluteus maximus muscle. The authors concluded the inferior gluteal nerve was less likely to be the source of postoperative gluteal pain after sacrospinous ligament fixation; however, as the pudendal nerve branches from S2-4, it was more likely to be implicated in postoperative gluteal pain.

A study by Ploteau et al. (2017) explored the anatomical position of the pudendal nerve in people with pudendal neuralgia. In 100 patients who met the Nantes criteria, 145 pudendal nerves were surgically decompressed via a transgluteal approach. At least one segment of the pudendal nerve was compressed in 95 of the patients, either in the infrapiriform foramen, ischial spine, or Alcock’s canal. In 74% of patients, nerve entrapment was between the sacrospinous ligament and the sacrotuberous ligament. Anatomical variants were found in 13% of patients, often with a transligamentous course of the nerve.

When the pudendal nerve is caught in the narrow space between ligaments in the pelvis, diagnosing the source of pain is paramount. Research supports a gluteal approach in releasing the entrapped nerve. Post-surgical care falls into the hands of pelvic floor therapists, so taking “Pudendal Neuralgia and Nerve Entrapment: Evaluation and Treatment” may be something to consider in order to provide optimal care.

Ploteau, S, Cardaillac, C, Perrouin-Verbe, MA, Riant, T, Labat, JJ. (2016). Pudendal Neuralgia Due to Pudendal Nerve Entrapment: Warning Signs Observed in Two Cases and Review of the Literature. Pain Physician. 19(3):E449-54

Florian-Rodriguez, ME, Hare, A, Chin, K, Phelan, JN, Ripperda, CM, Corton, MM. (2016). Inferior gluteal and other nerves associated with sacrospinous ligament: a cadaver study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 215(5):646.e1-646.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.025

Ploteau, S, Perrouin-Verbe, MA, Labat, JJ, Riant, T, Levesque, A, Robert, R. (2017). Anatomical Variants of the Pudendal Nerve Observed during a Transgluteal Surgical Approach in a Population of Patients with Pudendal Neuralgia. Pain Physician. 20(1):E137-E143

In the dim and distant past, before I specialised in pelvic rehab, I worked in sports medicine and orthopaedics. Like all good therapists, I was taught to screen for cauda equina issues – I would ask a blanket question ‘Any problems with your bladder or bowel?’ whilst silently praying ‘Please say no so we don’t have to talk about it…’ Fast forward twenty years and now, of course, it is pretty much all I talk about!

But what about the crossover between sports medicine and pelvic health? The issues around continence and prolapse in athletes is finally starting to get the attention it deserves – we know female athletes, even elite nulliparous athletes, have pelvic floor dysfunction, particularly stress incontinence. We are also starting to recognise the issues postnatal athletes face in returning to their previous level of sporting participation. We have seen the changing terminology around the Female Athlete Triad, as it morphed to the Female Athlete Tetrad and eventually to RED S (Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome) and an overdue acknowledgement by the IOC that these issues affected male athletes too. All of these issues are extensively covered in my Athlete & The Pelvic Floor’ course, which is taking place twice in 2018.

But what about pelvic pain in athletes?

How can we ensure that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is on the radar for a differential diagnosis, or perhaps a concomitant factor, when it comes to athletes presenting with hip, pelvis or groin pain? Gluteal injuries, proximal hamstring injuries, and pelvic floor disorders have been reported in the literature among runners: with some suggestions that hip, pelvis, and/or groin injuries occur in 3.3% to 11.5% of long distance runners.

How can we ensure that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is on the radar for a differential diagnosis, or perhaps a concomitant factor, when it comes to athletes presenting with hip, pelvis or groin pain? Gluteal injuries, proximal hamstring injuries, and pelvic floor disorders have been reported in the literature among runners: with some suggestions that hip, pelvis, and/or groin injuries occur in 3.3% to 11.5% of long distance runners.

In Podschun’s 2013 paper ‘Differential diagnosis of deep gluteal pain in a female runner with pelvic involvement: a case report’, the author explored the case of a 45-year-old female distance runner who was referred to physical therapy for proximal hamstring pain that had been present for several months. This pain limited her ability to tolerate sitting and caused her to cease running. Examination of the patient's lumbar spine, pelvis, and lower extremity led to the initial differential diagnosis of hamstring syndrome and ischiogluteal bursitis. The patient's primary symptoms improved during the initial four visits, which focused on education, pain management, trunk stabilization and gluteus maximus strengthening, however pelvic pain persisted. Further examination led to a secondary diagnosis of pelvic floor hypertonic disorder. Interventions to address the pelvic floor led to resolution of symptoms and return to running.

‘This case suggests the interdependence of lumbopelvic and lower extremity kinematics in complaints of hamstring, posterior thigh and pelvic floor disorders. This case highlights the importance of a thorough examination as well as the need to consider a regional interdependence of the pelvic floor and lower quarter when treating individuals with proximal hamstring pain.’ (Podschun 2013)

Many athletes who present with proximal hamstring tendinopathy or recurrent hamstring strains, display poor ability to control their pelvic position throughout the performance of functional movements for their sport: along with a graded eccentric programme, Sherry & Best concluded ‘…A rehabilitation program consisting of progressive agility and trunk stabilization exercises is more effective than a program emphasizing isolated hamstring stretching and strengthening in promoting return to sports and preventing injury recurrence in athletes suffering an acute hamstring strain’

If you are interested in learning more about how pelvic floor dysfunction affects both male and female athletes, including broadening your differential diagnosis skills and expanding your external treatment strategy toolbox, then consider coming along to my course ‘The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor’ in Chicago this June or Columbus, OH in October.

The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), Mountjoy et al 2014: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/48/7/491

‘DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DEEP GLUTEAL PAIN IN A FEMALE RUNNER WITH PELVIC INVOLVEMENT: A CASE REPORT’ Podschun A et al Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Aug; 8(4): 462–471. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3812833/

‘A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains’ Sherry MA, Best TM J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004 Mar;34(3):116-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15089024

The expression, “the canary in the coal mine” comes from a long ago practice of coalminers bringing canaries with them into the coalmines. These birds were more sensitive than humans to toxic gasses and so, if they became ill or died, the coalminers knew they had to get out quickly. The canaries were a kind of early warning signal before it was too late. Even though the practice has been discontinued, the metaphor lives on as a warning of serious danger to come.

Osteoporosis, which means porous bones, has been called a silent disease because often an individual doesn’t know he or she has it until they break a bone. The three common areas of fracture are the wrist, the hip, or the spine. Osteoporosis fractures are called fragility fractures, meaning they happen from a fall of standing height or less. We should not break a bone just by a fall unless there is an underlying cause which makes our bones fragile.

Wrist fractures typically happen when a person starts to fall and puts his or her arms out to catch themselves. They often are seen in the Emergency Department but seldom followed up with an Osteoporosis workup. According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation’s Capture the Fracture program, 80% of fracture patients are never offered screening and / or treatment for osteoporosis. As professionals working with patients who often have co-morbidities, we can be the ones to screen for osteoporosis and balance problems, particularly if our patients have a history of fractures. These screens include the following:

Wrist fractures typically happen when a person starts to fall and puts his or her arms out to catch themselves. They often are seen in the Emergency Department but seldom followed up with an Osteoporosis workup. According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation’s Capture the Fracture program, 80% of fracture patients are never offered screening and / or treatment for osteoporosis. As professionals working with patients who often have co-morbidities, we can be the ones to screen for osteoporosis and balance problems, particularly if our patients have a history of fractures. These screens include the following:

1. Check for the three most common signs of osteoporosis:

a. History of fractures

b. Hyper-kyphosis of the thoracic spine

c. Loss of height equal or greater than 4 cm.

2. Grip Strength

Low grip strength in women is associated with low bone density1

3. Rib-pelvic distance- less than two fingerbreadths.

With the patient standing with their back to you, arms raised to 90 degrees, check the distance from the lowest rib to the iliac crest. Two fingerbreadths or less may be indicative of a vertebral fracture.

A prior fracture is associated with an 86% increased risk of any fracture based on a 2004 meta-analysis by Kanis, Johnell, and De Laet in Bone 2. Fracture predicts fracture. It is our duty as professionals and as human beings to intervene by screening and referring out even if this is not the primary reason we are treating this patient. Fractures from osteoporosis can be devastating, resulting in increased risk of mortality at worst and a diminished quality of life at best. Look for the canaries in the coal mine. Our patients deserve to live the quality of life they envision.

Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT, CEEAA teaches the Meeks Method for Osteoporosis Management seminars for Herman and Wallace around the country.

1. Dixon WG et al. Low grip strength is associated with bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in women. Rheumatology 2005;44:642-646

2. Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, et al. (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 35:375

Influencing pelvic floor EMG activity through hip joint mobilization and positioning

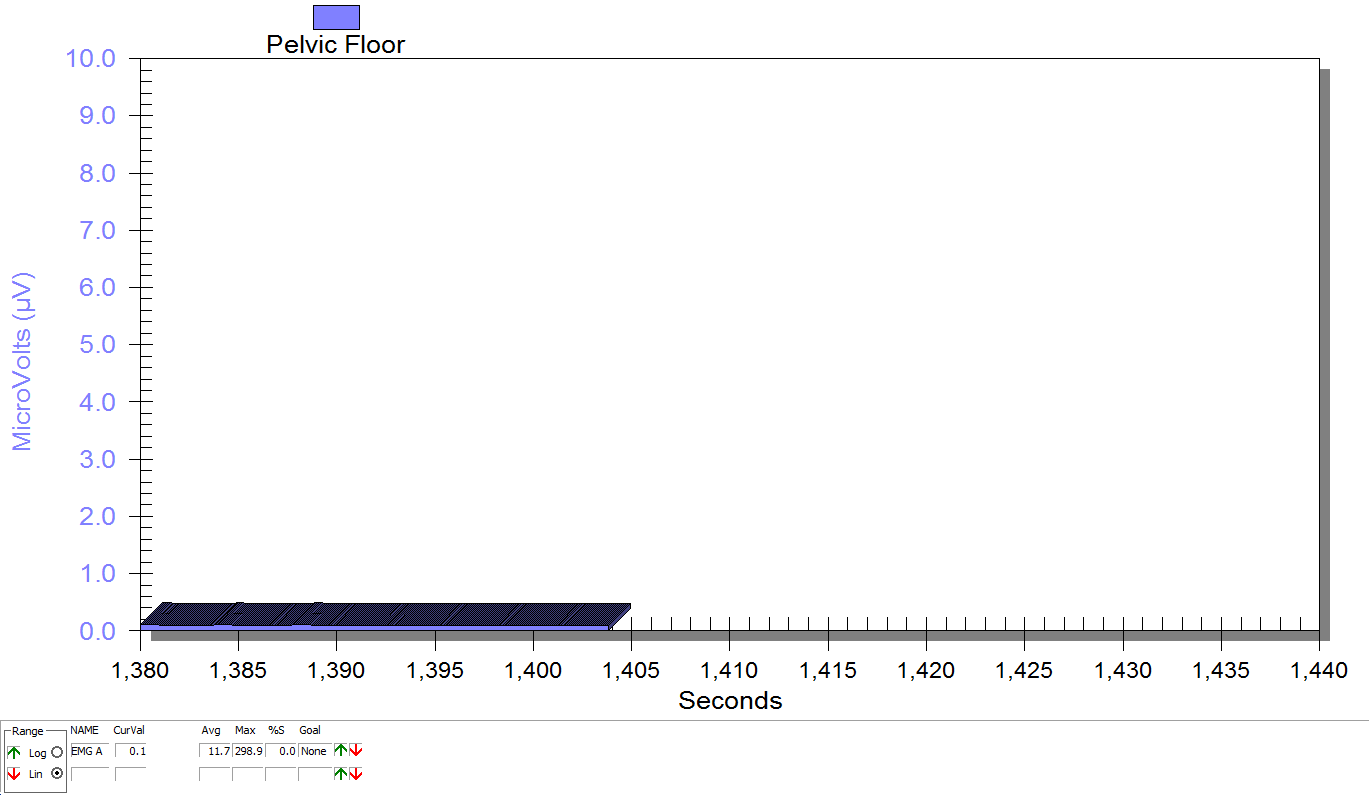

EMG is a helpful tool to observe pelvic floor muscle activity and how it is influenced by everything from regional musculoskeletal factors and mucosal health, to client motor control, awareness, and comfort.

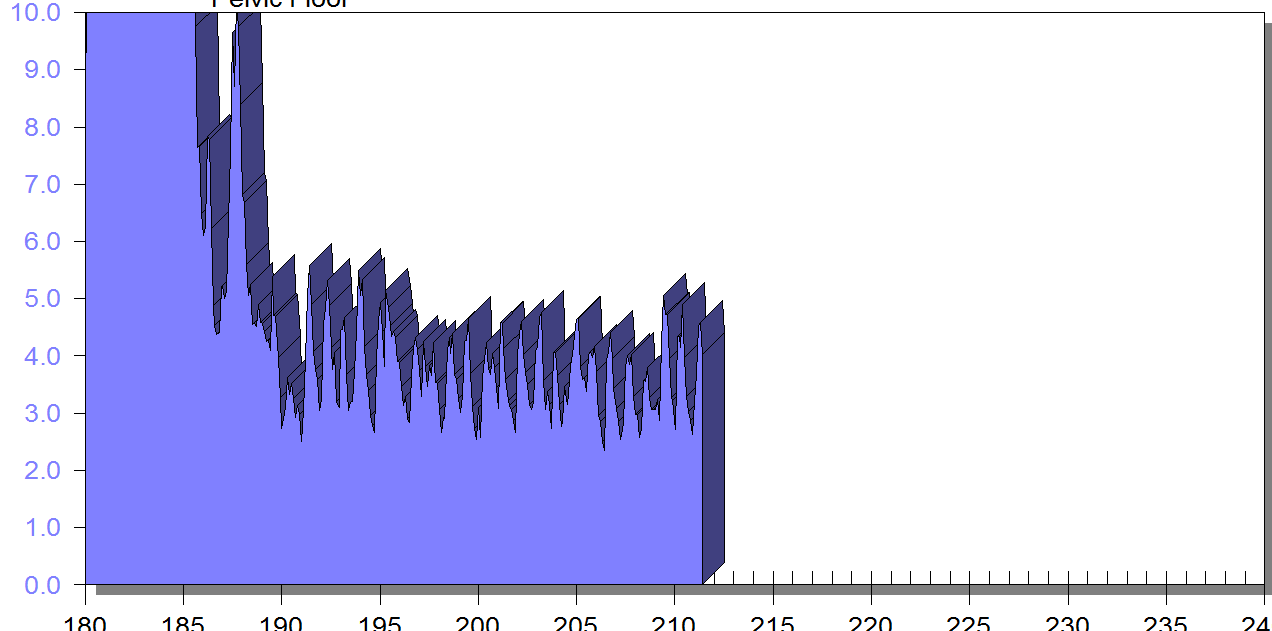

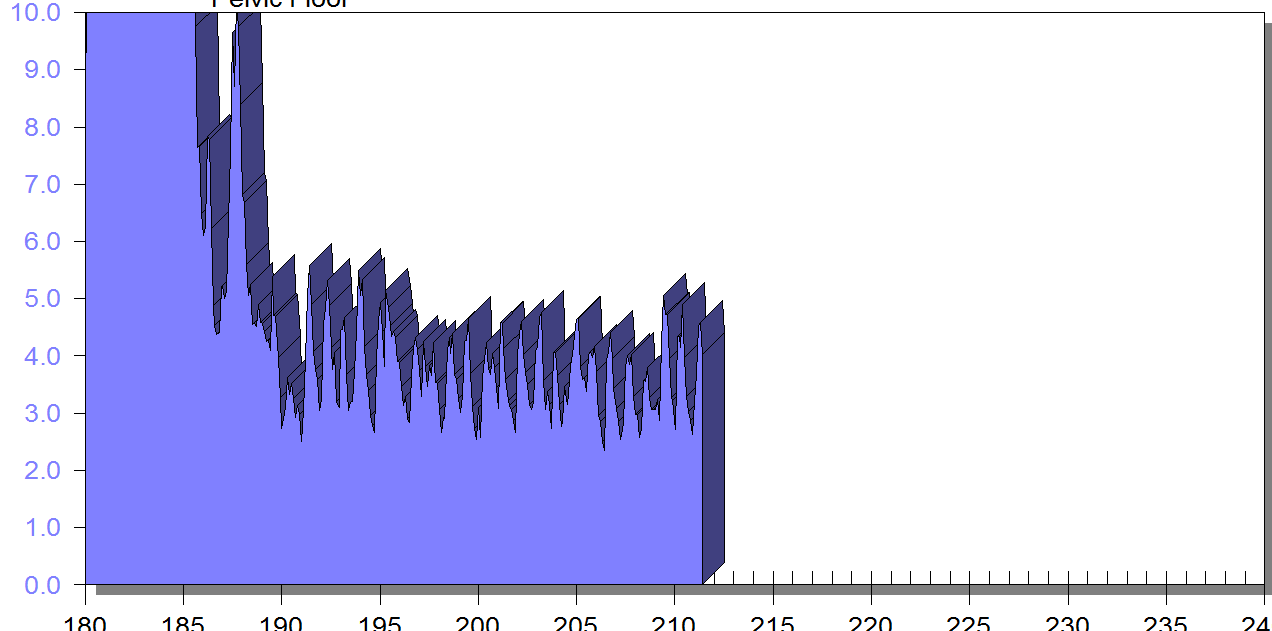

In this post I will discuss the case of one client who was referred for dyspareunia treatment, and whose SEMG findings are outlined in Figures 1-3. She had validated test item clusters for right hip labral tear as well as femoral acetabular impingement, in addition to right sided pelvic floor muscle overactivity and sensitivity with less than 3 ounces of palpation pressure.

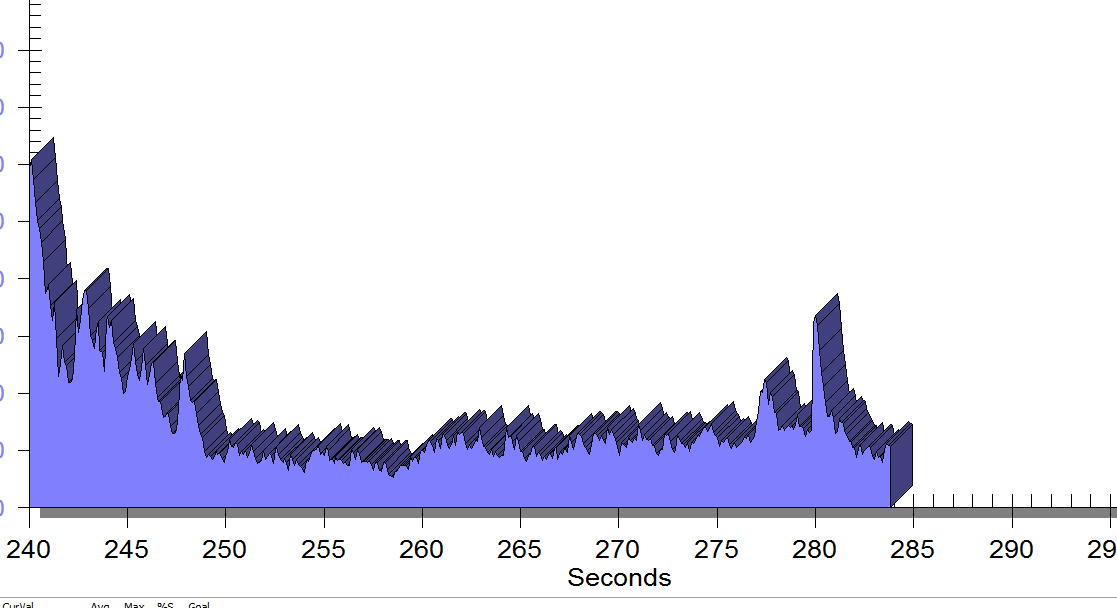

The figures below demonstrate peri-anal SEMG response of pelvic floor muscles within a single treatment session, which included sacral unloading in supine as well as hip joint mobilization to demonstrate the relationship between her pelvic floor and her hips. Our focus for this SEMG downtraining treatment was to enable her to understand the connection between her pelvic floor muscle holding patterns and her body’s preferences to remain out of ranges of motion that impinged and irritated her hip.

By creating a clear understanding of how the client could 'listen" to her muscle activity via SEMG (as well as her kinesthetic awareness of her own comfort), she began to understand the difference between body and hip position, her pelvic floor muscle activity, and her pain during intercourse.

Pelvic floor motor control with normalized respiration, orthopedic considerations of sexual activity, and other physical therapy as well as multidisciplinary treatments were integrated into her ability to resume intercourse. The lens of SEMG, however, was a powerful tool to help her make the connection between her hip and its influence on her pelvic floor overactivity and symptoms.

Musculoskeletal co-morbidities in pelvic pain are common, requiring the clinician to have a set of test item clusters to scan and clear key structures, as well as the ability to convey this information without creating distress to the client when positive findings are discovered. For example, labral tears and subchondral cysts are common findings in asymptomatic clients and physical therapy plays a key role in reducing client fear, avoiding symptom provocation, reducing regional muscle overactivity, as well as facilitating movement and strengthening in painfree ROM.

Although this case example describes intraarticular hip dysfunction as a driver of this clients PFM overactivity, Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain is a course that is designed to cover comprehensive key test item clusters for a fundamental pelvic pain scan exam of intrapelvic as well as extrapelvic drivers, to ensure the clinician understands the contributing factors that can influence or be influenced by the pelvic floor. This course is best suited for physical therapists and physical therapist assistants who are looking to create an organized approach to their scan exam for pelvic pain. For non-physical therapists, this can be a powerful introduction to the skill set and vocabulary needed to create a multidisciplinary team with a PT in the treatment of these clients.

FIGURE 1

PFM EMG at rest in supine, knees bent, feet on table (peri-anal SEMG electrode placement)

FIGURE 2

Same position, only with sacral unweighting by placing folded towels on either side of sacrum, unweighting all pressure from sacrum. Immediate report of increased comfort in buttocks, hips and pelvis.

Figure 3

Supine, sacrum unweighted as in figure 2, after multidirecitonal hip joint mobilizaiton.

Groh, Herrera. A comprehensive review of hip labral tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2009 Jun; 2(2): 105–117. Published online 2009 Apr 7. doi: 10.1007/s12178-009-9052-9

Yosef, et al. Multifactorial contributors to the severity of chronic pelvic pain in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec;215(6):760.e1-760.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.023. Epub 2016 Jul 18.

Consider combing long, curly hair. Untangling the top layer is not so bad, but once half the hair is tamed, there is often a mangled mess lurking underneath. Sometimes the lumbar spine gets all the primping to relieve pain, but the sacroiliac joint is harboring the knots, such as when a lumbar rhizotomy leaves a patient’s satisfaction a little fuzzy.

A 2017 study by Rimmalapudi and Kumar investigated the incidence of sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction being diagnosed in patients after undergoing lumbar radiofrequency rhizotomy of the medial branches of lower lumbar dorsal rami for chronic facet-mediated low back pain. The authors used a retrospective chart review of 96 patients who had the procedure performed, and 50 subjects responded to the 2 follow ups and were included in the study. Their choice of control was a limitation in this study, as they compared the results to a different study (DePalma et al., 2011) with a similar population that did not have the lumbar rhizotomy performed. Of the 50 patients (66% female, 34% male), 35 (70%) were subsequently diagnosed with SI joint pain; whereas, in the comparison study, only 18% of the patients had SI pain. The assessment of SI dysfunction in this study was by clinical exam, and the DePalma et al. study used diagnostic tests. The authors concluded the following: clinicians should suspect underlying SI joint pain post-lumbar rhizotomy; careful evaluation of the SI joint should be performed pre and post procedure; and, diagnostic joint blocks should be performed to confirm SI dysfunction. They suggested using criteria of 80-100% relief as opposed to the currently accepted >50% after a diagnostic facet block because residual pain from an underlying condition may arise after lumbar rhizotomy.

A 2017 study by Rimmalapudi and Kumar investigated the incidence of sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction being diagnosed in patients after undergoing lumbar radiofrequency rhizotomy of the medial branches of lower lumbar dorsal rami for chronic facet-mediated low back pain. The authors used a retrospective chart review of 96 patients who had the procedure performed, and 50 subjects responded to the 2 follow ups and were included in the study. Their choice of control was a limitation in this study, as they compared the results to a different study (DePalma et al., 2011) with a similar population that did not have the lumbar rhizotomy performed. Of the 50 patients (66% female, 34% male), 35 (70%) were subsequently diagnosed with SI joint pain; whereas, in the comparison study, only 18% of the patients had SI pain. The assessment of SI dysfunction in this study was by clinical exam, and the DePalma et al. study used diagnostic tests. The authors concluded the following: clinicians should suspect underlying SI joint pain post-lumbar rhizotomy; careful evaluation of the SI joint should be performed pre and post procedure; and, diagnostic joint blocks should be performed to confirm SI dysfunction. They suggested using criteria of 80-100% relief as opposed to the currently accepted >50% after a diagnostic facet block because residual pain from an underlying condition may arise after lumbar rhizotomy.

Stelzer et al., (2017) published another retrospective study on lumbar neurotomy or SI joint lateral branch cooled radiofrequency (RF) neurotomy, looking at pain reduction and medication decrease, depending on BMI, gender, and sports. Facet-mediated pain is accountable for 31-45% of low back pain, and 18-30% is SI joint mediated. The study started with 160 patients who had undergone procedures, and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scores, quality of life, BMI, medication use, and pain management satisfaction were assessed before, 1 month after (n=160), 6 months after (n=73), and 12 months (n=89) after treatment. Group 1 (n=43) had neurotomy of the medial branch of L4-5 and L5-S1 facet joint, medial branch L3 and L4, and dorsal ramus L5. Group 2 (n=109) received cooled RF treatment of the SIJ, SIJ lateral branch of the posterior rami S1–S3, and rami dorsalis of L5. Group 3 (n=8) had various areas treated according to their disease process. The authors determined from these treatments that a 95% probability of significant pain reduction could last 12 months; medication usage decreased; lower BMI had slightly better results than >30BMI; no significant difference between males and females; and, involvement in sports 1-3 times a week for 30 minutes showed improvement in quality of life.

These studies prove we need to evaluate our lumbar and sacroiliac joint patients as thoroughly as possible in order to avoid unnecessary procedures or at least to help direct the treatment to the appropriate area. We should always equip ourselves with knowledge of medical procedures our patients may undergo and expand our own clinical competence and skill. Patients benefit from what is inside our heads and how we use it, not how well-groomed our hair appears.

Rimmalapudi, V. K., & Kumar, S. (2017). Lumbar Radiofrequency Rhizotomy in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Increases the Diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction in Subsequent Follow-Up Visits. Pain Research & Management, 2017, 4830142. http://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4830142

M. J. DePalma, J. M. Ketchum, and T. Saullo. (2011). What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Medicine. 12(2), 224–233.

Stelzer, W., Stelzer, V., Stelzer, D., Braune, M., & Duller, C. (2017). Influence of BMI, gender, and sports on pain decrease and medication usage after facet–medial branch neurotomy or SI joint lateral branch cooled RF-neurotomy in case of low back pain: original research in the Austrian population. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 183–190. http://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S121897

An 80 year old lady who had seen a physical therapist where I once worked in Naperville, IL, just completed a marathon and a 5k race in one weekend. She is undoubtedly one woman who can change our perception of the “elderly,” but we all know her strength and ability are not the norm. The geriatric patients coming to therapy for pelvic floor disorders are more likely to be too frail to have run a mile this century, and they are most likely struggling with functional ADLs, as research suggests.

A study by Erekson et al., (2015) looked into the prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability among women over 65 years of age looking for the best treatment for their pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). A major concern was the presence of frailty being equated with poorer surgical outcomes. The 150 women in the study were tested with the Fried Frailty Index to measure frailty, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Score for cognitive screening, and the Katz ADL score for functional status. Pelvic organ prolapse was present in 65.3% women, urinary incontinence in 20.7%, overactive bladder in 9.3%, and anal incontinence in 0.7%. Sixteen percent of women were considered frail and 42% were “prefrail.” Dementia was determined in 21.3% of women, and functional disability in 30.7%. Pelvic floor dysfunction in women with frailty caused a significantly greater life-impact than in normal and pre-frail women. Forty-six percent of the subjects opted for surgery, but only women with functional disability, not impaired cognition nor frailty, were less likely to choose non-surgical intervention. The authors concluded that being able to identify women with PFD with risk factors of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability may help predict the risk of complications before surgery and help encourage behavioral changes and provide the appropriate pre and post-operative care for each woman.

A study by Erekson et al., (2015) looked into the prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability among women over 65 years of age looking for the best treatment for their pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). A major concern was the presence of frailty being equated with poorer surgical outcomes. The 150 women in the study were tested with the Fried Frailty Index to measure frailty, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Score for cognitive screening, and the Katz ADL score for functional status. Pelvic organ prolapse was present in 65.3% women, urinary incontinence in 20.7%, overactive bladder in 9.3%, and anal incontinence in 0.7%. Sixteen percent of women were considered frail and 42% were “prefrail.” Dementia was determined in 21.3% of women, and functional disability in 30.7%. Pelvic floor dysfunction in women with frailty caused a significantly greater life-impact than in normal and pre-frail women. Forty-six percent of the subjects opted for surgery, but only women with functional disability, not impaired cognition nor frailty, were less likely to choose non-surgical intervention. The authors concluded that being able to identify women with PFD with risk factors of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability may help predict the risk of complications before surgery and help encourage behavioral changes and provide the appropriate pre and post-operative care for each woman.

Silay et al., (2016) published a review on urinary incontinence (UI) in elderly women, relating its association with other geriatric conditions. Sixty-four females aged 65 and older were evaluated using the Turkish version of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) to assess UI and quality of life. Activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were used to evaluate functional status, and the Mini Mental State Examination was used for cognitive assessment. The comorbidities, pharmaceuticals, falls, and body mass index (BMI) of patients were also recorded. Results showed the subjects’ rate of urinary incontinence was 40.6%, and 28.1% of the women had their quality of life impacted. There was a statistically significant association using logistic regression between UI and quality of life, functional status, and comorbidity. Sadly, 50% of patients thought UI was normal with aging, 34.6% had been embarrassed to tell anyone about it, and 15.3% said they did not know UI was something for which medical treatment could be given.

Understanding how to manage frailty, cognitive issues, and functional deficits of our elderly patients can positively impact treatment outcomes. We should always strive to educate our patients and be aware of conditions that may be affecting or even contributing to their PFD. The Geriatric Pelvic Floor Rehab course can enlighten therapists on a score of comorbidities and techniques for handling those patients who are not sporting a marathon finisher medal to their physical therapy visits!

Erekson, E. A., Fried, T. R., Martin, D. K., Rutherford, T. J., Strohbehn, K., & Bynum, J. P. W. (2015). Frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability in older women with female pelvic floor dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal, 26(6), 823–830. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2596-2

K. Silay, S. Akinci, A. Ulas, A. Yalcin, Y.S. Silay, M.B. Akinci, I. Dilek, B. Yalcin. (2016). Occult urinary incontinence in elderly women and its association with geriatric condition. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 20(3): 447-451.

In the comedy, Kindergarten Cop, Detective John Kimble may only have had a headache, not a tumor, but sometimes our patients do have a tumor. One of my patients was actually just diagnosed with a brain tumor after responding poorly to a cortisone injection for her neck pain. Tumors in other areas of the body, even in the pelvis, can be the source of symptoms that may seem like a nerve entrapment. This is a serious consideration to be given when diagnosing pudendal neuralgia.

In 2008, Labat et al. published the “Diagnostic Criteria for Pudendal Neuralgia by Pudendal Nerve Entrapment” in Neurourology and Urodynamics . A group in Nantes, France, established criteria in 2006, since the diagnosis is primarily clinical in nature. The results of this paper concluded the five essential diagnostic criteria (Nantes criteria) are as follows:

In 2008, Labat et al. published the “Diagnostic Criteria for Pudendal Neuralgia by Pudendal Nerve Entrapment” in Neurourology and Urodynamics . A group in Nantes, France, established criteria in 2006, since the diagnosis is primarily clinical in nature. The results of this paper concluded the five essential diagnostic criteria (Nantes criteria) are as follows:

- Pain located in the anatomical region of the pudendal nerve.

- Pain worsened with sitting.

- Pain does NOT awaken the patient at night.

- Negative sensory loss upon clinical exam.

- Pain is relieved with an anesthetic pudendal nerve block.

A recent study by Waxweiler, Dobos, Thill, & Bruyninx explored the Nantes criteria as related to choosing surgical candidates for pudendal neuralgia from nerve entrapment. They looked at how a patient’s response to the anesthetic block corresponded to appropriate selection of patients for a successful surgical outcome. Six of 34 patients in the study had a negative anesthetic pudendal nerve block, and 100% of those patients had no symptom relief after surgery. In contrast, 64% of the patients who met all five of the Nantes criteria responded positively to surgery. The authors concluded confirmation of the 5th criteria as essential for predicting success of surgery for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment.

In Pain Physician in 2016, Ploteau et al. present two case studies where consideration of the Nantes criteria helped diagnose rare tumors in patients who demonstrated red flags during examination. Warning signs such as nocturnal awakening, point-specific pain, pain of a neuropathic nature, and neurological deficits cannot be overlooked when a patient presents with pudendal neuralgia. In the case studies presented, the 31 year old woman did not have pain exacerbated with sitting and woke at night with pain, and the 62 year old woman was awakened at night with pain. Each patient had magnetic resonance imaging performed, and rare diagnoses of endometrial stromal sarcoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma were made, respectively. The tumors arose in the ischiorectal fossa and compressed the pudendal nerve, presenting as pudendal neuralgia in atypical forms requiring careful clinical examination and referral for MRI for accurate diagnosis.

Although a tumor rarely exists, it is our duty to recognize signs and symptoms that do not follow established criteria. Paying attention to what your patients say just may be lifesaving. Proper diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia is essential and sometimes falls in our hands.

Labat, JJ., Riant, T., Robert, R., Amarenco, G., Lefaucheur, JP., Rigaud, J. (2008). Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourology and Urodynamics. 27(4):306-10. doi: 10.1002/nau.20505.

Waxweiler, C., Dobos, S., Thill, V., Bruyninx, L. (2016). Selection criteria for surgical treatment of pudendal neuralgia. Neurourology and Urodynamics. doi:10.1002/nau.22988.

Ploteau, S., Cardaillac, C., Perrouin-Verbe, M. , Riant, T., & Labat, J. (2016). Pudendal Neuralgia Due to Pudendal Nerve Entrapment: Warning Signs Observed in Two Cases and Review of the Literature. Pain Physician. 19:E449-E454.