“My butt hurts.” This is such a common subjective complaint in my practice as a manual therapist, and many patients insist it must be a muscle problem or jump to the conclusion it must be “sciatica.” I often tell patients if they did not get shot or bit directly in the buttocks, the pain is most likely referred from nerves that originate in the spine. Although blunt trauma to the buttocks can certainly be the culprit for pain in the gluteal region, a basic understanding of the neural contribution is essential for providing appropriate treatment and a sensible explanation for patients.

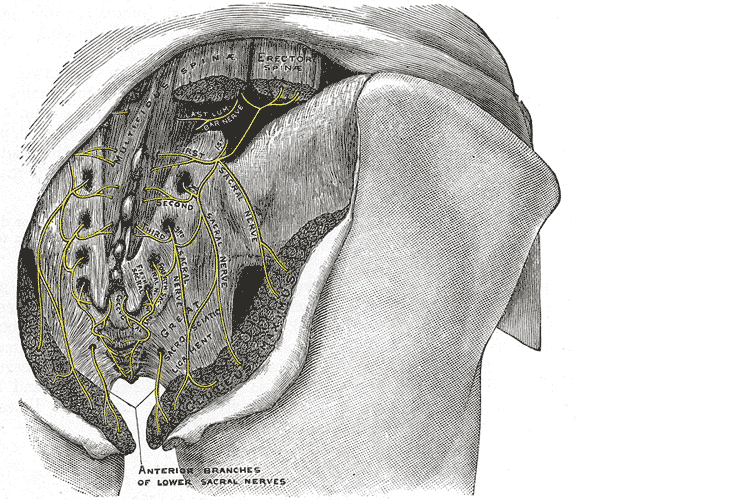

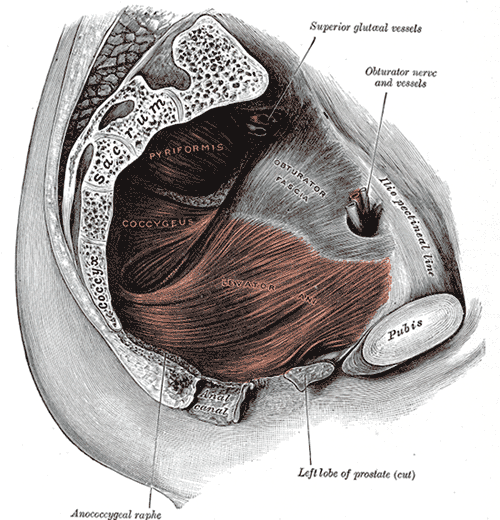

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

A publication by Lung and Lui (2018) describes the superior gluteal nerve. It comes from the dorsal (posterior) divisions of the L4, L5, and S1 nerve roots of the sacral plexus and innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae muscles. When this nerve is damaged or compressed, a Trendelenburg gait results because of paralysis of the gluteus medius muscle. The gluteus minimus and tensor fascia latae muscles are also innervated by the superior gluteal nerve and form the “abductor mechanism” together with the gluteus medius to stabilize the pelvis in midstance as the opposite leg is in swing phase. The superior gluteal nerve courses with the inferior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, and coccygeal plexus, but it is the only nerve to exit the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle.

Iwananga et al., (2018) presents a very recent article regarding the innervation of the piriformis muscle, which has been suspected to be the superior gluteal nerve, by dissecting each side from ten cadavers. Often the piriformis muscle can be compromised through total hip replacements with a posterior approach, hip injuries, or chronic pain disorders. This particular study verifies there is no singular nerve that innervates the piriformis muscle, and the most common innervation sources are the superior gluteal nerve (70% of the time) and the ventral rami of S1 (85% of the time) and S2 (70% of the time). The inferior gluteal nerve and the L5 ventral ramus were each found to be part of the innervation only 5% of the time.

Wang et al., (2018) focused on what causes gluteal pain with lumbar disc herniation, particularly at L4-5, L5-S1. They emphasize the important factor that dorsal nerve roots have sensory fibers and ventral roots contain motor neurons, and spinal nerves are mixed nerves, since they have ventral and dorsal roots. They discuss other contributing nerves, but continuing our focus on the superior gluteal nerve, it stems from L4-S1 ventral rami and not only allows movement of gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and gluteus maximus, it also provides sensation to the area. This nerve can certainly produce pain in the gluteal region when irritated. In lumbar disc herniation of L4-5 or L5-S1, the ventral rami of L5 or S1 can be comprised or irritated at the level of the nerve root and provoke gluteal pain because they mediate sensation in that area.

Once the superior gluteal nerve (or any sacral nerve) is implicated as the root of pain, should we just shrug our shoulders and send them to pain management? I strongly suggest we learn how to address the issue in therapy using our hands with manual techniques and appropriate exercises. The Sacral Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment course should be a priority on your bucket list of continuing education to help alleviate any further pain in the butt.

Lung K, Lui F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Superior Gluteal Nerve. [Updated 2018 Dec 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535408/

Iwanaga J, Eid S, Simonds E, Schumacher M, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. (2018). The Majority of Piriformis Muscles are Innervated by the Superior Gluteal Nerve. Clinical Anatomy. doi: 10.1002/ca.23311. [Epub ahead of print]

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Yan, Y., Zhang, L., Guo, C., Peng, Z., & Kong, Q. (2018). Possible pathogenic mechanism of gluteal pain in lumbar disc hernia. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 19(1), 214. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-2147-y

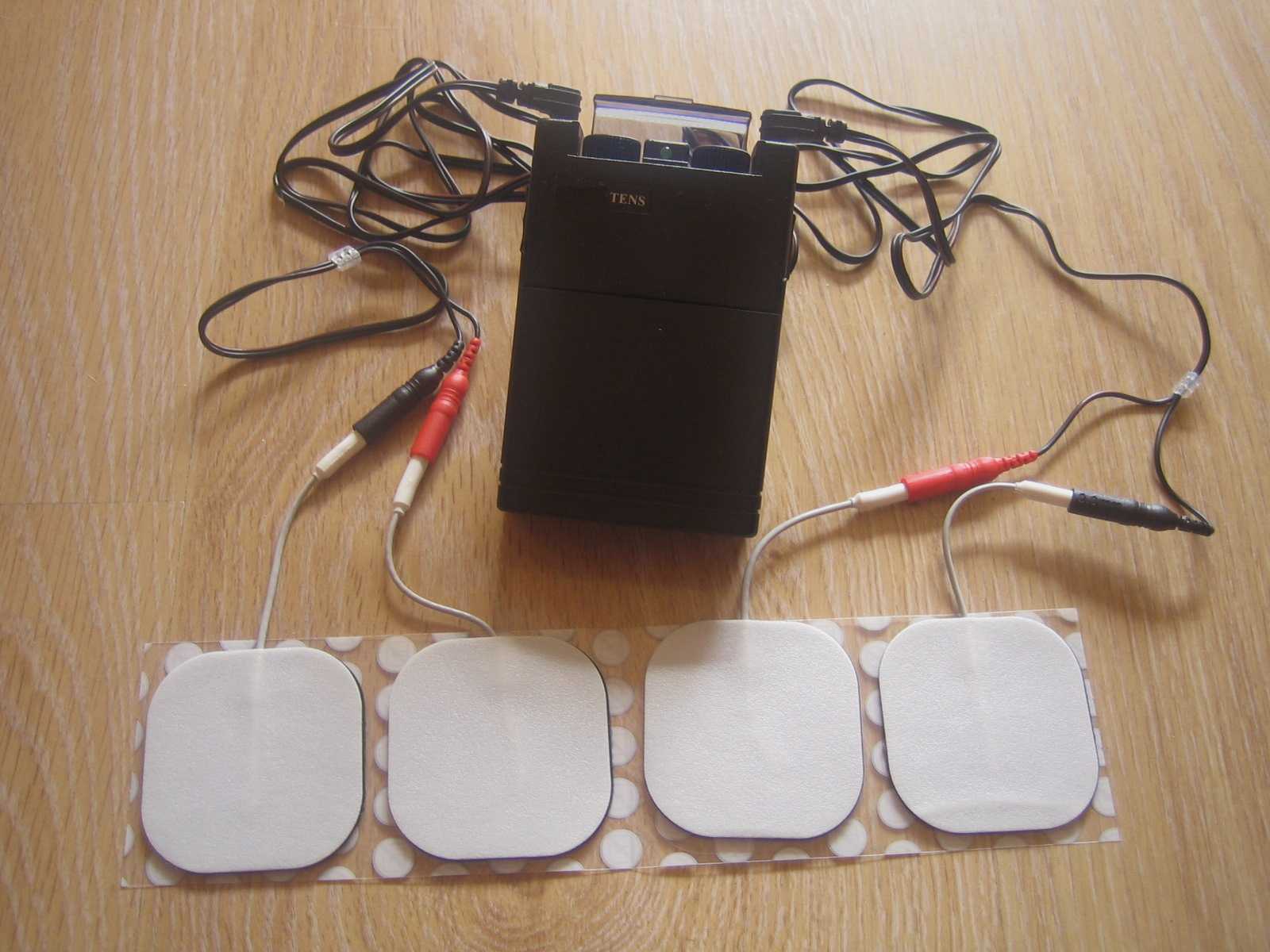

Tibial nerve stimulation has been shown in the literature to be effective for individuals experiencing idiopathic overactive bladder in randomized controlled trials. A systematic review was performed by Schneider, M.P. et al. in 2015 looking at safety and efficacy of its use in neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Many variables were examined in this review, which included 16 studies after exclusion. The review looked at:

- Acute stimulation (used during urodynamic assessment only)

- Chronic stimulation (6-12 weeks of daily-weekly use)

- Percutaneous or transcutaneous (frequencies, pulse widths, perception thresholds, durations)

- Urodynamic parameter changes baseline to post treatment

- Post void residual changes

- Bladder diary variables

- Patient adherence to tibial nerve stimulation

- Any adverse events

The exact mechanism of these types of neuromodulation stimulation procedures remains unclear, however it does appear to play a role in neuroplastic reorganization of cortical networks via peripheral afferents. No specific literature is currently available for the mechanism on action related to neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Different applications of neuromodulation however have been studied in the neurogenic populations.

One of the randomized controlled trials they report on included 13 people with Parkinson disease. The researchers looked at a comparison between the use of transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (n = 8) and sham transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (n=5). Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) or sham stimulation was delivered to the people with Parkinson disease 2x/week for 5 weeks, 30-minute sessions (10 total sessions). Unilateral electrode placement was utilized, first electrode applied below the left medial malleolus and second electrode 5 cm cephalad. Confirmation of placement was obtained with left great toe plantar flexion. It is important to note the use of the stimulation intensity is reduced to below the motor threshold during the active treatment to direct the stimulation via peripheral afferents.

Urodynamic testing was performed at baseline and post treatment and revealed statistically significant differences with greater volumes at strong desire and urgency in the TTNS group. Additionally, the TTNS group experienced a 50% reduction in nocturia whereas in the sham group nocturia frequency remained the same. A three-day bladder diary completed by each of the groups also revealed significant positive changes in frequency, urgency, urge urinary incontinence and hesitancy only in the TTNS group.

Conservative management of neurogenic bladder in populations such as Parkinson disease is very important. These individuals experience lower quality of life ratings related to lower urinary tract dysfunction, higher risk of falling with needs to rush to the bathroom, their caregivers experience a higher level stress and burden of care, and tolerance to anticholinergic medications is very poor with multiple unwanted side effects that compound and worsen other symptoms that might be present from the disease process.

Please join us for Neurologic Conditions and Pelvic Floor Rehab to learn how you can help your patients using this modality as one option. Participate in a lab session to learn electrode placement and other parameters to achieve best clinical results for your patients.

1. Perissinotto, M. C., D'Ancona, C. A. L., Lucio, A., Campos, R. M., & Abreu, A. (2015). Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and its impact on health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 42(1), 94-99.

2. Schneider, M. P., Gross, T., Bachmann, L. M., Blok, B. F., Castro-Diaz, D., Del Popolo, G., ... & Kessler, T. M. (2015). Tibial nerve stimulation for treating neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: a systematic review. European urology, 68(5), 859-867.

The following is the first in a series on self-care and preventing practitioner burnout from faculty member Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC. Jennafer is the co-author and co-instructor of the Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation course along with Nari Clemons, PT, PRPC.

Part 1: Boundaries

“I just want you to fix me.” How many times have we heard this statement from our patients? And how do we respond? In my former life as a “rescuer” this statement would be a personal challenge. I wanted to be the fixer, find the solution and identify the thing that no one else had seen yet. Then, if I am being completely honest, bask in the glory of being the “miracle worker” and “never giving up” on my patient.

If you recognize that this attitude was going to run me into some problems, kudos to you. If you are thinking, “well of course, isn’t that your job as a pelvic floor physical therapist?” Please read on.

If you recognize that this attitude was going to run me into some problems, kudos to you. If you are thinking, “well of course, isn’t that your job as a pelvic floor physical therapist?” Please read on.

On my very first job performance review, when it came time to discuss my problem areas my supervisor relayed I was “too nice” and cited some examples: giving a patient a ride home after therapy (it was raining and she would have had to wait for the bus), coming in on Saturdays to care for patients (he was sick and couldn’t make it in during the week but was making really good progress). You get the picture. At the time, I didn’t understand how this could be something I needed to work on. I was going above and beyond and I got so much satisfaction from taking care of others!

Fast forward 10 years and add to my life a husband, two daughters, a teaching job, part time homeschooling, and writing course material. I was an emotional mess. Anxiety was my permanent state of mind. I gave my best to my patients while my family got my meager emotional leftovers. Something had to change and luckily it did. I got help and learned exactly what boundaries are and how to develop as well as enforce them.

There are several resources that discuss professional boundaries in health care, like this from Nursing Made Incredibly Easy. In this particular article, health care professionals are exhorted to stay in the “zone of helpfulness” and avoid becoming under involved or over involved with patients. Health care professionals are also urged to examine their own motivation. Am I using my relationship with my patient to fulfill my own needs? Am I over involved so that I can justify my own worth?

Here are some warning signs that you are straying away from healthy boundaries with patients and becoming over involved:

- Discussing your intimate or personal issues with a patient

- Spending more time with a patient than scheduled or seeing a patient outside of work

- Taking a patient's side when there's a disagreement between the patient and his or her close relations

- Believing that you are the only health care member that can help or understand a patient

For some people, certain patients who push professional boundaries will cause the therapist to feel threatened and under activity is the result. This might result in talking badly about the patient to other staff, distancing ourselves, showing disinterest in their case, or failing to utilize best care practices for the patient.

Per Remshard 2012, “When you begin to feel a bit detached, stand back and evaluate your interactions. If you sense that boundaries are becoming blurred in any patient care situation, seek guidance from your supervisor. A sentinel question to ask is: ‘Will this intervention benefit the patient or does it satisfy some need in me?’”

Healthy professional boundaries are imperative for us and for our patients. Boundaries also help prevent burnout. Remshard delineates what healthy boundaries look like:

- Treat all patients, at all times, with dignity and respect.

- Inspire confidence in all patients by speaking, acting, and dressing professionally.

- Through your example, motivate those you work with to talk about and treat patients and their families respectfully.

- Be fair and consistent with each patient to inspire trust, amplify your professionalism, and enhance your credibility.

If you struggle with professional and personal boundaries, you are not alone and you can get support. Consider talking with your supervisor, a counselor, reading a good book on the subject or taking Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation, a course offering through Herman and Wallace that was designed to help pelvic health professionals stay healthy and inspired while equipping therapists with new tools to share with their patients.

We hope you will join us for Boundaries, Self-Care, and Meditation this November 9-11, 2019 in San Diego, CA.

Look forward to my next blog where The Rescuer (me) needs Rescuing and learn about the Drama Triangle.

Remshardt, Mary Ann EdD, MSN, RN "Do you know your professional boundaries?" Nursing Made Incredibly Easy!: January/February 2012 - Volume 10 - Issue 1 - p 5–6 doi: 10.1097/01.NME.0000406039.61410.a5

Diagnosing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction can be tricky. Therapists need to rule out lumbar spine and the hip, and sometimes there is more than one area causing pain and limiting functional mobility. Typically, ruling in SIJ dysfunction is done by pain provocation tests and load transfer tests. Once the SIJ has been ruled in, then therapists can use a variety of treatments. Often those treatments include therapeutic exercise, joint manipulation, and Kinesio tape. But which intervention is the most effective?

A recent study looked at three physical therapy interventions for treatment for SIJ (sacroiliac joint) dysfunction and assessed which was the most effective (Al-Subahi, M 2017). The authors did a systematic review of the literature. The articles were from 2004-2014, written in English, with male and female participants. This review included a variety of experiment types from randomized control trials to case studies. Of the 1114 studies, only 9 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Four of the nine studies used manipulation, three used Kinesio Tape, and the three used exercise. One study did both exercise and manipulation, and was looked at in both interventions. All categories had at least one randomized control trial.

For the manipulation intervention, all studies showed a decrease in pain and disability at follow up. The follow ranged from 3 to 4 days to 8 weeks. Disability was measured using the Oswestry Disability Index. One study did manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation to lumbar and SIJ manipulation and showed improvement with manipulation to SIJ or SIJ and lumbar. The review did not disclose the type of lumbar manipulation, but did state the SIJ manipulation was a side bend and rotation position with an inferior and lateral force to ASIS (anterior superior iliac spine). Another study did either a SIJ manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation or a mechanical force with manual assistance. One studied did manipulation and home exercises but did not record exercise interventions. The last study did the same SIJ manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation as in previous study combined with exercise. The exercises are mentioned below.

For the exercise intervention, the studies did primarily stabilization exercises that were either isometric or isotonic eccentric or concentric. Quick PT school review, in isometric exercises the muscle does not change length, while in isotonic eccentric exercises the muscle is being lengthened under load, and isotonic concentric is the muscle shortening under load. All three studies showed decrease in pain. The first study had 7 participants and combined manipulation and exercise. The exercises consisted of 12% max voluntary contraction and eccentric loading quads in supine with hips at 90 degrees, and concentrically loading hamstrings in prone. The second study was a case study and performed 8 lumbo-pelvic-femoral stabilization exercises for 8 weeks. Fun fact: this case study was written by my Therapeutic Exercise teacher in PT school who did a lot of Postural Restoration based exercises. The last study, had 22 participants and educated and provided exercises on deep abdominal and multifidus muscles and do complete these exercises during functional movements throughout the day. These participants were follow up a year later and had decreased pain compared to laser group.

For the Kinesio tape (Kinesio tape) intervention, the studies did not find that Kinesio tape was not an effective intervention, however the follow up ranged from immediately after applying tape to 4 weeks afterwards. In the first study, a randomized controlled trial with 60 participants, the Kinesio tape was applied in sitting with 25% tension of 4 strips making a star pattern over the point of maximal pain. The Kinesio tape was compared to placebo tape and showed equal improvement in pain and disability. The other two studies applied a different taping technique where the Kinesio tape was applied. One applied the tape over erector spinae and internal oblique muscles bilaterally and in the other study the Kinesio tape was applied with 25% tension over external obliques, a second strip was placed from ASIS to PSIS in side-lying, and then a third strip was placed along rectus abdominis muscle. In this same study the tape was applied for weeks (6x/week for 9 hours/day).

In summary, the authors note that all three interventions help decrease pain and disability in women and men with SIJ dysfunction. The authors suggest that manipulation may be the most effective. Kinesio tape showed no significant difference between placebo tape. Exercise was effective, but less so than manipulation.

This review has a lot of limitations. The variety of experiment types with varying degrees of evidence, small number of participants, and lack of blinding. Most studies had a limited follow up ranging from 3-4 days to 12 months. The outcome measures varied greatly. Most studies had pain scores as the outcome measure, though one study only used inclination meter of anterior pelvic tilt. Use of a consistent objective measure in addition to perceived pain and disability would have helped. Only 1 study did pain provocation tests and that study was a case study whose intervention focused on Kinesio-taping.

As physical therapists we want to provide effective evidence-based practice, and we want to provide individualized compassionate care. It is hard to make a direct line between this study’s recommendations and clinical application based on the numerous limitations. I agree with the authors that manipulation and exercise are bread and butter to physical therapists. I disagree about Kinesio tape not being an effective treatment. Is Kinesio tape going to create boney alignment changes? Likely not. Is Kinesio tape (or any other tape) going to give proprioceptive feedback and possibly help calm sensory pathways? Yes. If a patient likes being taped, and thinks it will help, then I will tape them. Even if taping is just placebo effect; it’s still an effect.

Al-Subahi, M., Alayat, M., Alshehr, M.A., et al. (2017) The effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: A systematic review. J Phys. Ther. Sci. 29: 1689-1694.

Rehabilitative ultrasound imaging has been used in clinical practice for well over a decade now. It has been used for core stabilization, as well as with female incontinence patients. In recent years, transperineal ultrasound imaging has emerged as a useful tool for assessing prolapses and identifying other women’s health issues in the anterior compartment.

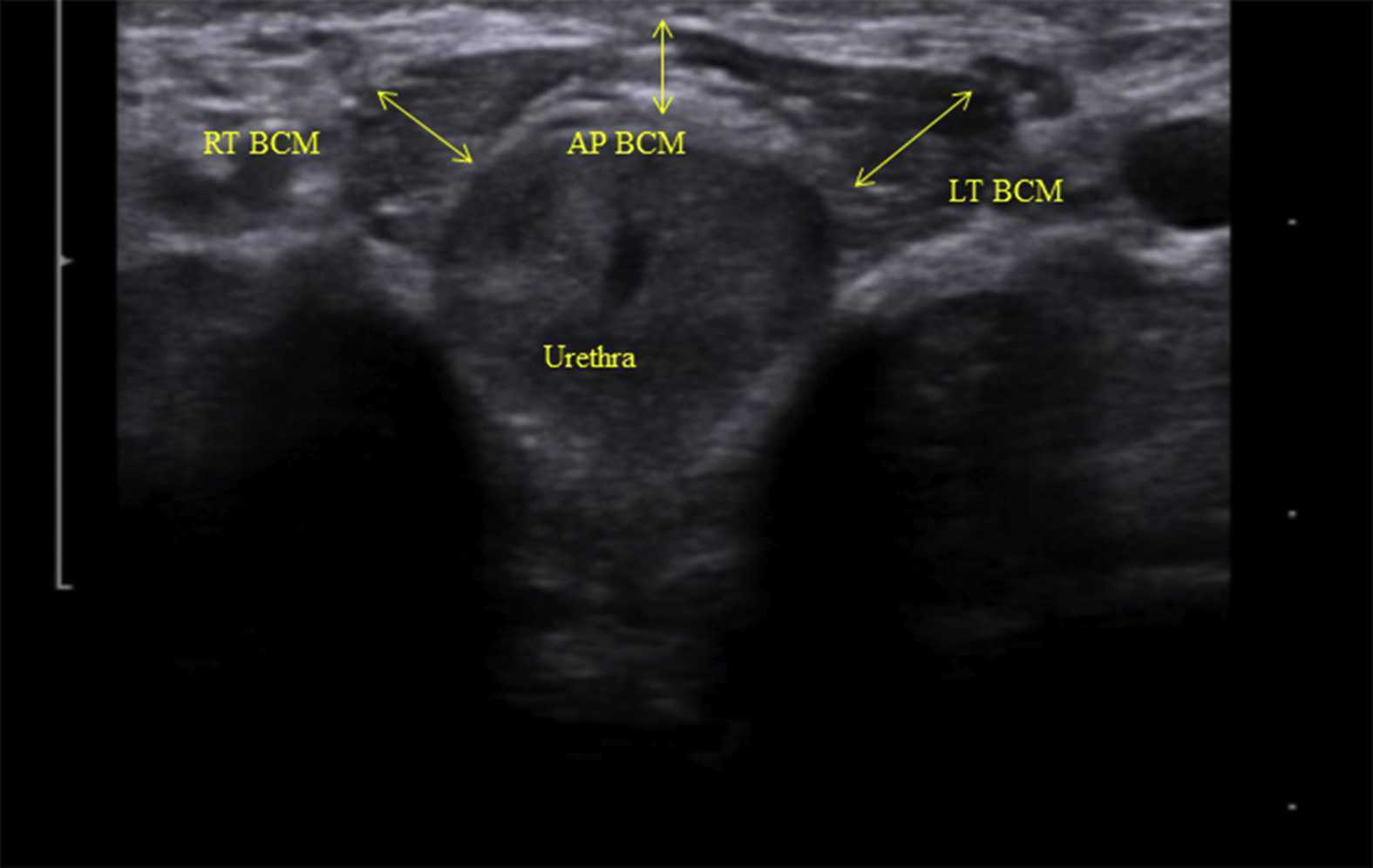

Like other things in men’s pelvic health, the use of ultrasound imaging for rehabilitation has lagged behind that in women’s pelvic health. Ryan Stafford is a researcher that is working to change that. In 2012, Stafford began looking at the normal responses to pelvic floor contractions and what is seen on ultrasound in men. He has since taken his research further to examine differences in men that present with post-prostatectomy incontinence. Stafford, van den Hoorn, Coughlin, and Hodges performed a study looking at the dynamic features of activation of specific pelvic floor muscles, and anatomical parameters of the urethra. The study included forty-two men who had undergone prostatectomy. Some of these men were incontinent and others remained continent. Transperineal ultrasound imaging was used to obtain images of the pelvic structures during a cough, and a sustained maximal contraction. The research team calculated displacements of pelvic floor landmarks with contraction, as well as anatomical features including urethral length, and resting position of the ano-rectal and urethra-vesical junctions.

Like other things in men’s pelvic health, the use of ultrasound imaging for rehabilitation has lagged behind that in women’s pelvic health. Ryan Stafford is a researcher that is working to change that. In 2012, Stafford began looking at the normal responses to pelvic floor contractions and what is seen on ultrasound in men. He has since taken his research further to examine differences in men that present with post-prostatectomy incontinence. Stafford, van den Hoorn, Coughlin, and Hodges performed a study looking at the dynamic features of activation of specific pelvic floor muscles, and anatomical parameters of the urethra. The study included forty-two men who had undergone prostatectomy. Some of these men were incontinent and others remained continent. Transperineal ultrasound imaging was used to obtain images of the pelvic structures during a cough, and a sustained maximal contraction. The research team calculated displacements of pelvic floor landmarks with contraction, as well as anatomical features including urethral length, and resting position of the ano-rectal and urethra-vesical junctions.

The data was analyzed and combinations of variables that best distinguished men with and without incontinence were reported. Several important components were identified in the study. Striated urethral sphincter activation, as well as bulbocavernosus and puborectalis muscle activation were significantly different between men with and without incontinence. When these two parameters were examined together, they were able to correctly identify 88.1% of incontinent men. They further reported that poor function of the puborectalis and bulbocavernosus could be compensated for if the man had good striated urethral sphincter function. However, the puborectalis and bulbocavernosus had less potential to compensate for poor striated urethral sphincter function. This is important for a therapist that works with post prostatectomy patients to know. This can explain part of why some men improve and do so well after a prostatectomy and others don’t, even with therapy to help. If the striated urethra sphincter is damaged and its normal responses are changed during surgery, then incontinence after prostatectomy may be more likely.

Using ultrasound imaging, the therapist can examine and see exactly where a man is deficient in response; whether it is the puborectalis, or the striated urethra sphincter. It is exciting to see this new research and see how rehabilitative ultrasound imaging can influence men’s pelvic health! Come and learn how to use ultrasound imaging for your men’s pelvic health patients as well as your women’s health and back pain patients! You will see how ultrasound imaging can change your practice and how much your patients will enjoy seeing real-time images of their contractions! Thanks to our partnership with The Prometheus Group, this course includes hands-on training on the latest in pelvic ultrasound imaging.

1. Stafford R, Ashton-Miller J, Constantinou C, et al. Novel insights into the dynamics of male pelvic floor contractions through transperineal ultrasound imaging. J. Urol. 2012; 188: 1224-30.

2. Stafford RE, van den Hoorn W, Couglin G, Hodges P. Postprostatectomy incontinence is related to pelvic floor displacements observed with trans-perineal ultrasound imaging. Neurol and Urodyn. 2018; 37:658-665.

Image credit Gupta et al. 2016 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2016.11.002 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214388216300881#fig2

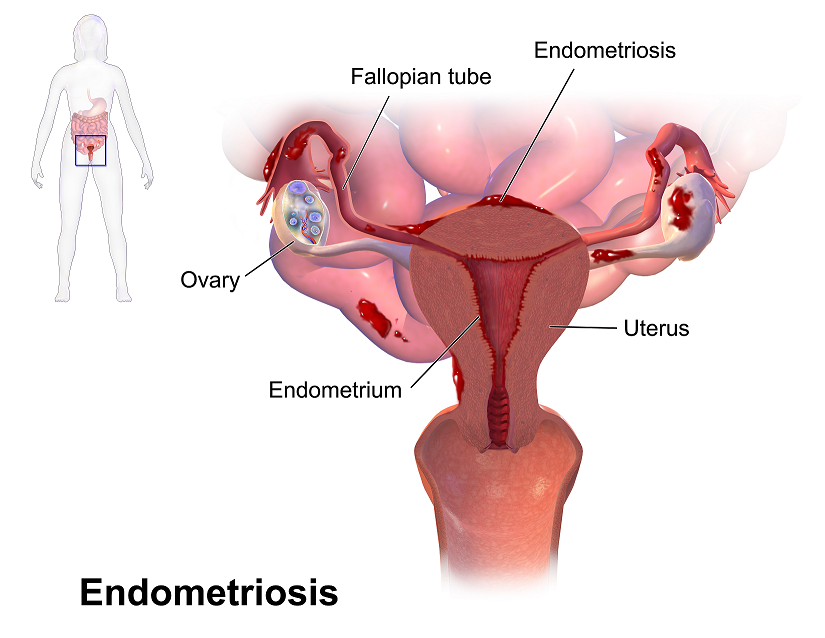

Recent data suggests that there are about 4 million American women diagnosed with endometriosis, but that 6/10 are not diagnosed. Currently, using the gold standard for diagnosis there are potentially 6 million American woman that may experience the sequelae of endometriosis without having appropriate management or understanding the cause of their symptoms.

The gold standard for endometriosis is laparoscopy either with or without histologic verification of endometrial tissue outside of the uterus. However, there is a poor correlation between disease severity and symptoms. The Agarwal et al study suggests a shift to focus on the patient rather than the lesion and that endometriosis may better be defined as “menstrual cycle dependent, chronic, inflammatory, systemic disease that commonly presents as pelvic pain”. There is often a long delay in symptom appreciation and diagnosis that can range from 4-11 years. The side effects of this delay are to the detriment of the patient; persistent symptoms and effect of quality of life, development of central sensitization, negative effects on patient-physician relationship. If this disease continues to go untreated it may affect fertility and contribute to persistent pelvic pain.

The authors suggest a clinical diagnosis with transvaginal ultrasound for patients presenting with persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, patient history, have symptoms consistent with endometriosis, or other findings suggestive of endometriosis. The intention of using transvaginal ultrasound is to make diagnosis more accessible and limit under diagnosis. It is not intended to minimize laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool or treatment option.

The authors suggest a clinical diagnosis with transvaginal ultrasound for patients presenting with persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, patient history, have symptoms consistent with endometriosis, or other findings suggestive of endometriosis. The intention of using transvaginal ultrasound is to make diagnosis more accessible and limit under diagnosis. It is not intended to minimize laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool or treatment option.

The algorithm for a clinical diagnosis evaluates patient presentation of the following:

- Symptoms including persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea or painful menstruation cramps, deep dyspareunia or pain with deep vaginal penetration, cyclic dyschezia or straining for soft stools, cyclic dysuria or pain with urination, cyclic catamenial symptoms located in other systems such as acne or vomiting.

- Assessment of patient history including infertility, current chronic pelvic pain, or painful periods as an adolescent, previous laparoscopy with diagnosis, painful periods that are not responsive to NSAIDS, and a family history.

- Physical exam physicians assess for nodules in cul de sac, retroverted uterus, mass consistent with endometriosis, visible or obvious external endometrioma. Imaging should be ordered or performed.

- Clinical signs would consist of endometrioma with US, presence of soft markers (sliding sign) this is where the fundus of the uterus is compared to its neighboring structures and can indicate the immobility of those structures, and nodules or masses.

Of course, there are differential diagnosis for endometriosis, and those are symptoms of non-cyclical patterns of pain and bladder/bowel dysfunction that would indicate IBS, UTI, IC/PBS. A history of post-operative nerve entrapment of adhesions. Examination positive for pelvic floor spasm, severe allodynia in vulva and pelvic floor, masses such as fibroids. It is important to note that these other diagnoses can coexist with endometriosis and do not rule out possible endometriosis diagnosis.

Hopefully, diagnosing individuals earlier and possibly at a younger age would limit the disease severity and symptoms. This would allow this population to limit the possibility of central sensitization and pain persistence that can affect so much of daily life. Earlier diagnosis may affect infertility and allow this population to make informed decisions about family and career from a place of empowerment.

Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, Laufer MR, Leyland N, Missmer SA,Singh SS, Taylor HS, "Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action", American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2019), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.039.

The following is our interview with Jose Antonio (Tony) Rodriguez Jr, COTA. Tony practices in Laredo, TX where he is also studying Athletic Training at the Texas A & M University. He recently attended Pelvic Floor Level 1 and plans to continue pursuing pelvic rehabilitation with Herman & Wallace. He was kind enoguh to share some thoughts about his experiences with us. Thank you, Tony!

Tell us a bit about yourself!

I am a COTA in Laredo where I was born and raised. My goal is to provide pelvic floor therapy to my community. I have been in school for quite some time. I have associate's degrees as a paramedic and occupational therapy assistant. I studied nursing briefly (finished my junior year). My bachelors is in psychology. I’m currently studying athletic training in Texas A & M International University in Laredo. My ultimate academic goal is acquiring my doctorate in physical therapy.

What/who inspired you to become involved in pelvic rehabilitation?

I first came across pelvic floor when reading the description of a CE course where it mentions its relation to SI joint dysfunction so I figured I could use this as a trouble shooting tool for those athletes that had recurrent low back pain or suspected SI problems. I figured at the very least I would know when I was confronted with something that I needed to refer. Little did I know how important of a “puzzle piece” this type of knowledge would become in helping me see a more complete picture of the human body. I was often confronted with athletes that would have recurring lower back pain, hip pain, glute tightness, sciatic nerve pain, adductor tightness or pain, and felt I was missing something to be able to help them. Even with a basic understanding of pelvic floor rehab I was able to help athletes with the previously mentioned complaints. As my understanding grew, I felt it was necessary I take these Herman & Wallace courses so that I could actually treat my patients in a holistic manner.

What is your clinical environment like, and how can you implement pelvic rehab into your practice?

My clinical environment varies between outpatient pediatrics, outpatient geriatrics, and D2 university athletics. I use my pelvic rehabilitation tool box at the university. Mostly I am still learning but I try to screen for and educate my athletes on the important role the pelvic floor muscles play in every activity they carry through out the day. I try to convey the importance not just in sports but also in activities of daily living such as any difficulty with going to the bathroom to pain during sex. I figure the more young people I educate about pelvic floor therapy the better they’ll be to make an informed decision today or later on in life.

Do you feel your background and training as a COTA brings anything unique to your pelvic rehab patients?

I could probably say that my COTA training makes it easier to pick up on some of the behaviors people might be relying on to carry out their day while dealing with pelvic floor issues. They may or may not be aware they have a pelvic floor dysfunction but simply think that’s just how they are. Behaviors such as avoiding social events because such activities don’t fit well with their voiding schedule.

How does your background as a COTA influence your approach to patient care?

My approach as a COTA would force me to see a balance in life. I would have to ask myself all the ways pelvic floor dysfunction may affect my client's daily activities from the basics like voiding, resting, sleep, to enjoying their leisure activities. A person cannot rest adequately if they’re in pain. He or she cannot enjoy social activities being worried of an urge.

What patients or conditions are you hoping to start treating as you continue learning pelvic rehab?

I wish to continue learning and exposing myself to different areas pelvic floor rehabilitation may take me. I wish to look at this therapy through a wide lens. This way I can learn, help many, and keep myself a well-rounded therapist. If in the future I feel more drawn to a specific area I wish to pull from all the different areas I should have learned by then.

What role do you see pelvic health playing in general well-being?

I often tell my athletes that there is probably not a single gross motor movement that doesn’t cross the pelvic region directly or through fascia connection. It is simply how we are built. To try and pretend or ignore the importance of the pelvic floor is just leaving our patients out of the appropriate care they need. And now that I know about the role pelvic floor muscles have in our body it would be unethical not to advocate for my patients’ COMPLETE well-being, pelvic floor muscles included.

What's next for you and your practice?

My short-term goal is acquiring my athletic training state license. After that continue with the last four or five prerequisite classes I need to apply to a DPT program. The DPT is my ultimate goal within the next five or six years.

This post was written by the teaching team of Nancy Cullinane, PT, MSH, Kathy Golic, PT, and Terri Lannigan DPT, who took their talents to Nairobi, Kenya to teach a modified version of Herman & Wallace's Pelvic Floor Level 1 course.

At the end of week 1 of Kenyan Pelvic Floor Level 1, we are pleased to report that 35 physiotherapists are embracing pelvic health physical therapy. Our students are primarily from the Nairobi area, however a handful have traveled from rural areas. The majority of them have some aspect of women's health in their job duties, however, only two have previously performed internal pelvic floor muscle techniques. On the first day of class, we spent significant introductory time discussing course objectives, students' clinical experience, Kenyan healthcare delivery, and what they hoped to gain from us. One student described teaching herself skills she is using in her clinical practice from watching YouTube videos. Another student commented, "the only tool I have to treat my patients is the kegel exercise and it isn't working for many of my patients. I know I'm missing something and I hope to find it here." The concept of internal pelvic floor muscle evaluation and treatment is new in Kenya and this is the first presentation of this coursework. There was significant anxiety surrounding internal pelvic muscle examination lab in the course. Several participants were not aware what "internal examination" meant in the course description when they registered. One student did not return on day two because of it. Nonetheless, as soon as the first internal assessment lab was completed, the pace picked up considerably.

At the end of week 1 of Kenyan Pelvic Floor Level 1, we are pleased to report that 35 physiotherapists are embracing pelvic health physical therapy. Our students are primarily from the Nairobi area, however a handful have traveled from rural areas. The majority of them have some aspect of women's health in their job duties, however, only two have previously performed internal pelvic floor muscle techniques. On the first day of class, we spent significant introductory time discussing course objectives, students' clinical experience, Kenyan healthcare delivery, and what they hoped to gain from us. One student described teaching herself skills she is using in her clinical practice from watching YouTube videos. Another student commented, "the only tool I have to treat my patients is the kegel exercise and it isn't working for many of my patients. I know I'm missing something and I hope to find it here." The concept of internal pelvic floor muscle evaluation and treatment is new in Kenya and this is the first presentation of this coursework. There was significant anxiety surrounding internal pelvic muscle examination lab in the course. Several participants were not aware what "internal examination" meant in the course description when they registered. One student did not return on day two because of it. Nonetheless, as soon as the first internal assessment lab was completed, the pace picked up considerably.

These pioneering physiotherapists have developed new skills this past week for treating overactive bladder, mixed urinary incontinence, overactive pelvic floor muscles, prolapse, and diastasis recti. We have delved into discussion regarding sexual trauma and how cultural differences here in Kenya will impact the students' potential strategies in initiating conversations with their patients. Nine of our students are employed at Kenyatta National Hospital, the largest public hospital in Nairobi. Several are employed in private hospitals, who serve those citizens who pay to receive care in their respective systems. Many of our students are under-employed and some see patients privately in their homes, often for cash.

These pioneering physiotherapists have developed new skills this past week for treating overactive bladder, mixed urinary incontinence, overactive pelvic floor muscles, prolapse, and diastasis recti. We have delved into discussion regarding sexual trauma and how cultural differences here in Kenya will impact the students' potential strategies in initiating conversations with their patients. Nine of our students are employed at Kenyatta National Hospital, the largest public hospital in Nairobi. Several are employed in private hospitals, who serve those citizens who pay to receive care in their respective systems. Many of our students are under-employed and some see patients privately in their homes, often for cash.

We have additional Herman & Wallace Pelvic Floor Level 1 curriculum planned for week two, but we will also present the additional curriculum we have written specifically for these Kenyan physiotherapists. We will dedicate ample time toward connecting these motivated students with global mentoring resources, but we will also lay groundwork in helping them to set up a support network for pelvic health PT with each other.

We are honored and grateful to Herman & Wallace for donating Pelvic Floor Level 1 curriculum and to The Jackson Clinics Foundation for its history in changing physical therapy delivery in Kenya, including the financing of travel for this course. We are also thankful to Kenya Medical Training College for covering the cost of instructor lodging. At the half way mark of level 1, we feel we have already received so much more than we have given. We are especially grateful to the 35 course participants who will be changing the face of women's health physical therapy in Kenya from here on. Improving the quality of life for women improves the quality of life for families, and has an overall positive impact on the community.

The photography from this course is the creation of Marielle Selig, who acted as both technical support and official photographer for the Kenya Pelvic Floor Level 1 course. More of her work will be posted at https://mariselig.pixieset.com/.

The following is a guest submission from Alysson Striner, PT, DPT, PRPC. Dr. Striner became a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner (PRPC) in May of 2018. She specializes in pelvic rehabilitation, general outpatient orthopedics, and aquatics. She sees patients at Carondelet St Joesph’s Hospital in the Speciality Rehab Clinic located in Tucson, Arizona.

Myofascial pain from levator ani (LA) and obturator internus (OI) and connective tissues are a frequent driver of pelvic pain. As pelvic therapists, it can often be challenging to decipher whether pain is related to muscular and/or fascial restrictions. A quick review from Pelvic Floor Level 2B; overactive muscles can become functionally short (actively held in a shortened position). These pelvic floor muscles do not fully relax or contract. An analogy for this is when one lifts a grocery bag that is too heavy. One cannot lift the bag all the way or extend the arm all the way down, instead the person often uses other muscles to elevate or lower the bag. Over time both the muscle and fascial restrictions can occur when the muscle becomes structurally short (like a contracture). Structurally short muscles will appear flat or quiet on surface electromyography (SEMG). An analogy for this is when you keep your arm bent for too long, it becomes much harder to straighten out again. Signs and symptoms for muscle and fascial pain are pain to palpation, trigger points, and local or referred pain, a positive Q tip test to the lower quadrants, and common symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, pain, and/or dyspareunia.

For years in the pelvic floor industry there has been notable focus on vocabulary. Encouraging all providers (researchers, MDs, and PTs) to use the same words to describe pelvic floor dysfunction allowing more efficient communication. Now that we are (hopefully) using the same words, the focus is shifting to physical assessment of pelvic floor and myofascial pain. If patients can experience the same assessment in different settings then they will likely have less fear, and the medical professionals will be able to communicate more easily.

A recent article did a systematic review of physical exam techniques for myofascial pain of pelvic floor musculature. This study completed a systematic review for the examination techniques on women for diagnosis of LA and OI myofascial pain. In the end, 55 studies with 9460 participants; 99.8% were female, that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed. The authors suggest the following as good foundation to begin; but more studies will be needed to validate and to further investigate associations between chronic pelvic pain and lower urinary tract symptoms with myofascial pain.

The recommended sequence for examining pelvic myofascial pain is:

- Educate patient on examination process. Try to ease any anxiety they may have. Obtain consent for an examination

- Ask the patient to sit in lithotomy position

- Insert a single, gloved, lubricated index finger into the vaginal introitus

- Orient to pelvic floor muscles using clock face orientation with pubic symphysis at 12 o'clock and anus at 6 o'clock

- Palpate superficial and then deep pelvic floor muscles

- Palpate the obturator internus

- Palpate each specific pelvic floor muscle and obturator internus; consider pressure algometer to standardize amount of pressure

Authors recommend bilateral palpation and documentation of trigger point location and severity with VAS. They recommend visual inspection and observation of functional movement of pelvic floor muscles.

The good news is that this is exactly how pelvic therapists are taught to assess the pelvic floor in Pelvic Floor Level 1. This is reviewed in Pelvic Floor Level 2B and changed slightly for Pelvic Floor Level 2A when the pelvic floor muscles are assessed rectally. Ramona Horton also teaches a series on fascial palpation, beginning with Mobilization of the Myofascial Layer: Pelvis and Lower Extremity. I agree that palpation should be completed bilaterally by switching hands to make assessment easier for the practitioner who may be on the side of the patient/client depending on the set up. This is an important conversation between medical providers to allow for easy communication between disciplines.

Meister, Melanie & Shivakumar, Nishkala & Sutcliffe, Siobhan & Spitznagle, Theresa & L Lowder, Jerry. (2018). Physical examination techniques for the assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain: a systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 219. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.06.014

Birthing can be an unpredictable process for mothers and babies. With cases of fetal distress, the baby can require rapid delivery. Alternatively, in cases with cephalo-pelvic disproportion, the baby has a larger head, or the mother has a decreased capacity within the pelvis to allow the fetus to travel through the birthing canal. Additionally, the baby may have posterior presentation, colloquially known as “sunny side up” in which the baby’s occipital bone is toward the sacrum. With any of these situations, it is good to know c-sections are an option to safely deliver the child.

Women may also be inclined to try to get a c-section to avoid pelvic complication or tears or because of a history of a severe prior tear. As pelvic therapists, we know that the number of vaginal births and history of vaginal tears increase the risk of urinary incontinence and prolapse. Yet, many therapists are unfamiliar with the effects of c-section and the impact of rehab for diastasis.

Women may also be inclined to try to get a c-section to avoid pelvic complication or tears or because of a history of a severe prior tear. As pelvic therapists, we know that the number of vaginal births and history of vaginal tears increase the risk of urinary incontinence and prolapse. Yet, many therapists are unfamiliar with the effects of c-section and the impact of rehab for diastasis.

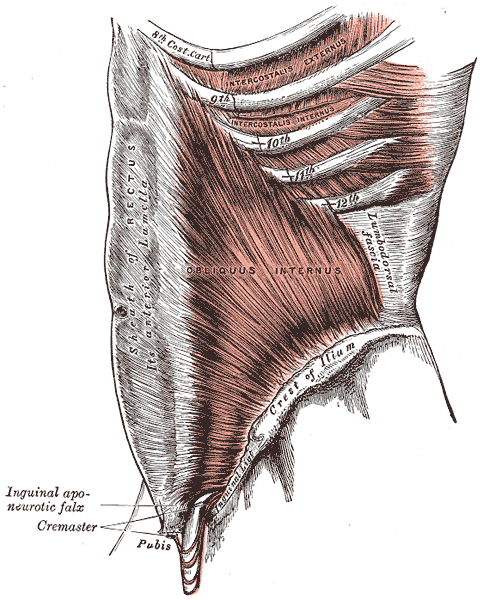

A 2008 dissection study of 37 cadavers studied the path of the ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves. The course of the nerves was compared with standard abdominal surgical incisions, including appendectomy, inguinal, pfannestiel incisions (the latter used in cesarean sections). The study concluded that surgical incisions performed below the level of the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS) carry the risk of injury to the ilioinguinal and iloiohypogastric nerves 1. Another 2005 study reported low transverse fascial incision risk injury to the ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves, and the pain of entrapment of these nerves may benefit from neurectomy in recalcitrant cases.2

Why does injury to the nerves matter? After pregnancy, patients may need rehab and retraining of their abdominal recruitment patterns for diastasis and stability. The ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves are the innervation for both the transverse abdominus and the obliques below the umbilicus. When we are working to retrain the muscles, certainly neural entrapment or poor firing can greatly impact the success of our intervention as rehab professionals. Interestingly, a study from Turkey showed patients had a significant increase in diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) with a history of 2 cesarean sections and increased parity and recurrent abdominal surgery increase the risk of DRA.2

A fourth study looked at 23 patients with ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment syndrome following transverse lower abdominal incision (such as a c-section). In this study, the diagnostic triad of ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment after operation was defined as 1) typical burning or lancinating pain near the incision that radiates to the area supplied by the nerve, 2). Clear evidence of impaired sensory perception of that nerve, and 3) pain relieved by local anaesthetic.4

One of the other symptoms we may see in an area of nerve damage is a small outpouching in the area of decreased innervation on the front lower abdominal wall.

So, what can we do with this information? The good news is that as rehab professionals, we can treat along the fascial pathway of the nerve to release in key areas of entrapment. We can mobilize the nerve directly. Neural tension testing can help us differentiate the nerve in question and we can use neural glides and slides after having freed up the nerve from the area of compression. Then, we can increase the communication of the nerve with the muscles by using specific, localized strengthening and stretch in areas of prior compression. All of these techniques are taught in in our course, Lumbar Nerve Manual Treatment and Assessment. Come join us in San Diego May 3-5, 2019 to learn how to differentially diagnose and treat entrapment of all of the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Okiemy, G., Ele, N., Odzebe, A. S., Chocolat, R., & Massengo, R. (2008). The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. The anatomic bases in preventing postoperative neuropathies after appendectomy, inguinal herniorraphy, caesareans. Le Mali medical, 23(4), 1-4.

Whiteside, J. L., & Barber, M. D. (2005). Ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric neurectomy for management of intractable right lower quadrant pain after cesarean section: a case report. The Journal of reproductive medicine, 50(11), 857-859.

Turan, V., Colluoglu, C., Turkuilmaz, E., & Korucuoglu, U. (2011). Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in the population of young multiparous adults in Turkey. Ginekologia polska, 82(11).

Stulz, P., & Pfeiffer, K. M. (1982). Peripheral nerve injuries resulting from common surgical procedures in the lower portion of the abdomen. Archives of Surgery, 117(3), 324-327.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./