Chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP), defined as pain persisting for more than three months, affects approximately 20% of adults worldwide, with a higher prevalence among vulnerable populations such as the elderly and those from diverse cultural backgrounds. The economic burden of CNCP is substantial, exceeding that of heart disease, diabetes, and cancer in countries like the United States. Beyond the financial implications, CNCP significantly impacts individuals' quality of life, leading to absenteeism, loss of productivity, and increased healthcare utilization.

Traditionally, CNCP management has focused on pharmacological interventions and physical therapies. However, emerging evidence underscores the importance of a holistic, person-centered approach that addresses various lifestyle factors, including nutrition. Healthy eating patterns are associated with reduced systemic inflammation, as well as lower risk and severity of chronic non-cancer pain and associated comorbidities.

Persisting low-grade systemic inflammation is associated with CNCP and multiple comorbid chronic health conditions. Diet plays a complex role in modulating systemic inflammation. Knowledge is expanding rapidly in this area and multiple links between diet and inflammation have been identified. Metabolic mechanisms associated with postprandial hyperglycemia and frequent and prolonged rises in plasma insulin levels, influenced by dietary intake, can produce systemic inflammation.

Nutritional Strategies for Pain Management

Evidence from a number of recent systematic reviews shows that optimizing diet quality and incorporating foods containing anti-inflammatory nutrients such as fruits, vegetables, long-chain and monounsaturated fats, antioxidants, and fiber leads to a reduction in pain severity and interference.

Non-nutritive bioactive compounds such as polyphenols mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation, as well as modulate pain experiences. One such mechanism operates through the inhibition of COX-2 in neuromodulating pathways. Polyphenols are found in a range of foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, cocoa, tea, coffee, and red wine.

Incorporating anti-inflammatory foods into one's diet can be a practical approach to managing CNCP. Emphasizing the consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats, while reducing the intake of processed foods and sugars, can help modulate inflammation and alleviate pain. Additionally, maintaining a balanced diet supports overall health, which is crucial for individuals dealing with chronic pain.

Adopting a healthy, anti-inflammatory diet can reduce systemic inflammation and alleviate pain severity, contributing to improved quality of life for individuals with CNCP. As research in this field continues to evolve, healthcare providers should consider incorporating nutritional strategies into comprehensive, person-centered pain management plans.

To learn more about essential digestion concepts, nourishment strategies, and the interconnected nature of physical and emotional health across the lifespan join Megan Prybil in her upcoming course, Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist on February 23-24, 2025. Whether at the beginning of your journey or well on your way down the path of integrative care, this continually updated and relevant course is a unique, not-to-be-missed opportunity.

Resources:

- Brain K, Burrows TL, Bruggink L, Malfliet A, Hayes C, Hodson FJ, Collins CE. Diet and Chronic Non-Cancer Pain: The State of the Art and Future Directions. J Clin Med. 2021 Nov 8;10(21):5203. doi: 10.3390/jcm10215203. PMID: 34768723; PMCID: PMC8584994.

- Nijs J, Malfliet A, Roose E, Lahousse A, Van Bogaert W, Johansson E, Runge N, Goossens Z, Labie C, Bilterys T, Van Campenhout J, Polli A, Wyns A, Hendrix J, Xiong HY, Ahmed I, De Baets L, Huysmans E. Personalized Multimodal Lifestyle Intervention as the Best-Evidenced Treatment for Chronic Pain: State-of-the-Art Clinical Perspective. J Clin Med. 2024 Jan 23;13(3):644. doi: 10.3390/jcm13030644. PMID: 38337338; PMCID: PMC10855981.

- Elma Ö, Brain K, Dong HJ. The Importance of Nutrition as a Lifestyle Factor in Chronic Pain Management: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2022 Oct 9;11(19):5950. doi: 10.3390/jcm11195950. PMID: 36233817; PMCID: PMC9571356.

- Lahousse A, Roose E, Leysen L, Yilmaz ST, Mostaqim K, Reis F, Rheel E, Beckwée D, Nijs J. Lifestyle and Pain following Cancer: State-of-the-Art and Future Directions. J Clin Med. 2021 Dec 30;11(1):195. doi: 10.3390/jcm11010195. PMID: 35011937; PMCID: PMC8745758.

- Nijs J, Reis F. The Key Role of Lifestyle Factors in Perpetuating Chronic Pain: Towards Precision Pain Medicine. J Clin Med. 2022 May 12;11(10):2732. doi: 10.3390/jcm11102732. PMID: 35628859; PMCID: PMC9145084.

Pain demands an answer. Treating persistent pain is a challenge for everyone; providers and patients. Pain neuroscience has changed drastically since I was in physical therapy school. This update comes from the International Spine and Pain Institute headed by the lead author Adriaan Louw, PT, PhD. If you are interested in reading more about persistent pain, I suggest reading the article in its entirety.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

This article brings together several comorbidities that pelvic physical therapists often encounter; fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease. The authors argue that all of these syndromes have many common symptoms and might be dependent on the provider that the individual goes to as to which diagnosis the individual receives. Often, once an individual has a diagnosis, he or she (more often she) then identifies with this label. The authors reason that once medical pathologies have been ruled out, then a more holistic, biopsychosocial approach may create better outcomes.

Pain neuroscience education is a way to explain pain to patients, often with analogies, with a focus on neurobiology and neurophysiology as it relates to that individuals pain experience. To be able to educate our patients, we as providers, must be able to understand neuromatrix, output, and threat. Moseley states “[p]ain is a multiple system output activated by an individual’s specific pain neuromatrix. The neuromatrix is activated whenever the brain perceives a threat”. If that sounds like gibberish, consider watching this TEDx talk by Lorimer Moseley on YouTube (the snake bite story is a favorite of mine):

What is a neuromatrix? Essentially, it is a pain map in the brain; a network of neurons spread throughout the brain, none of which deal specifically with pain processing. The way I visualize it is to think about what goes on when you think of your grandmother. There isn’t a grandmother center in the brain, but there are sights and smells (sensory), feelings (emotional awareness), and memories that all come up when you think about her. When we are overwhelmed with pain, those regions become taxed and the individual may have difficulty concentrating, sleeping, and/or may lose his/her temper more easily. Just as each person’s grandmother is different so is a person’s pain and the neuromatrix is affected by past experiences and beliefs.

Pain is an output. It is a response to a threat. When a person is exposed to a threatening situation, biological systems like the sympathetic nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, gastrointestinal system, and motor response system are activated. When a stress response occurs, these systems are either heightened or suppressed to help cope, thanks to the chemicals epinephrine and cortisol.

What is a threat? Threats can take a variety of forms; accidents, falls, diseases, surgeries, emotional trauma, etc. Tissues are influenced by how the individual thinks and feels, in addition to social and environmental factors. The authors propose that when individuals live with chronic pain, their body reacts as though they are under a constant threat. With this constant threat the system reacts and continues to react, and the nervous system is not allowed to return to baseline levels. This can create a patient presentation with immunodeficiency, GI sensitivity, poor motor control, and more. This sounds like most patients who walk into my clinic. The authors suggest that one system may be affected more and that can influence what the patient is diagnosed with even though the underlying biology is the same for many conditions. There are theories for why that happens; genetics, biological memory, or it could be the lens of the provider that the patient sees. There is a table in the article that shows symptoms, diagnosis, and current best evidence treatment for the conditions of fybromyalgia, chronic fatique syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic Lyme disease which is worth a look. The treatments all work to calm the central nervous system.

The authors go on to question the relationship between thyroid function and these conditions as changes in cortisol and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is fascinating, and confusing. Luckily, the Pelvic Floor Series Capstone course does a great job breaking it down.

Now that this hypothetical patient is in our treatment room what do we do? The authors suggest seeing these conditions for what they are: chronic pain conditions. They recommend that physical therapists see past the label that a patient may have picked up with a previous diagnosis, and keep the following in mind when treating these patients:

- They are hurting

- They are tired

- They may have lost hope

- They may be disillusioned by the medical community

- They need help

These people need the following from their medical providers:

- Compassion

- Dignity

- Respect

With empathy and understanding therapists can use skills in education, exercise and movement with the intent to improve system function (immune, neural, and endocrine), rather than fixing isolated mechanical deficits.

Louw, Adriaan PT, PhD; Schmidt, Stephen PT ; Zimney, Kory PT, DPT ; Puentedura, Emilio J. PT, DPT, PhD Treat the Patient, Not the Label: A Pain Neuroscience Update.[Editorial] Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 43(2):89-97, April/June 2019.

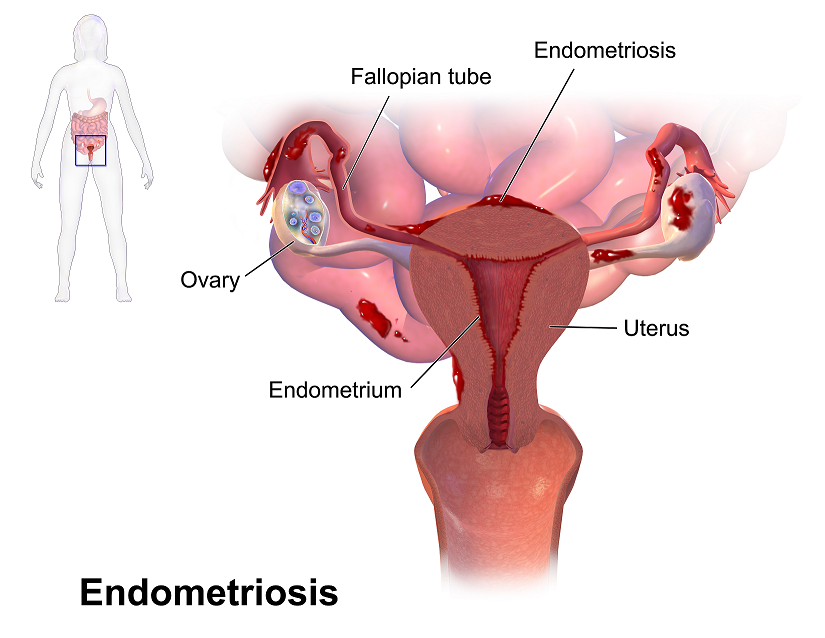

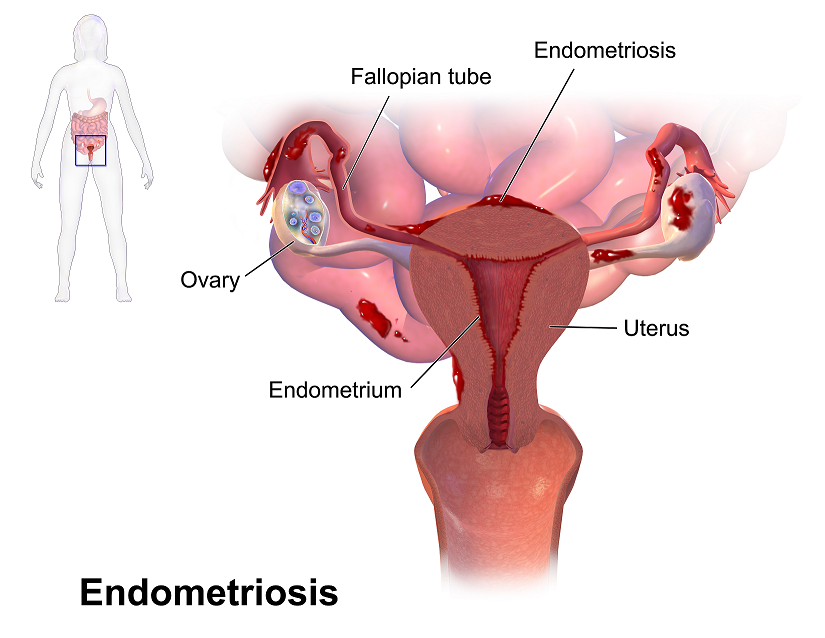

Recent data suggests that there are about 4 million American women diagnosed with endometriosis, but that 6/10 are not diagnosed. Currently, using the gold standard for diagnosis there are potentially 6 million American woman that may experience the sequelae of endometriosis without having appropriate management or understanding the cause of their symptoms.

The gold standard for endometriosis is laparoscopy either with or without histologic verification of endometrial tissue outside of the uterus. However, there is a poor correlation between disease severity and symptoms. The Agarwal et al study suggests a shift to focus on the patient rather than the lesion and that endometriosis may better be defined as “menstrual cycle dependent, chronic, inflammatory, systemic disease that commonly presents as pelvic pain”. There is often a long delay in symptom appreciation and diagnosis that can range from 4-11 years. The side effects of this delay are to the detriment of the patient; persistent symptoms and effect of quality of life, development of central sensitization, negative effects on patient-physician relationship. If this disease continues to go untreated it may affect fertility and contribute to persistent pelvic pain.

The authors suggest a clinical diagnosis with transvaginal ultrasound for patients presenting with persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, patient history, have symptoms consistent with endometriosis, or other findings suggestive of endometriosis. The intention of using transvaginal ultrasound is to make diagnosis more accessible and limit under diagnosis. It is not intended to minimize laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool or treatment option.

The authors suggest a clinical diagnosis with transvaginal ultrasound for patients presenting with persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, patient history, have symptoms consistent with endometriosis, or other findings suggestive of endometriosis. The intention of using transvaginal ultrasound is to make diagnosis more accessible and limit under diagnosis. It is not intended to minimize laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool or treatment option.

The algorithm for a clinical diagnosis evaluates patient presentation of the following:

- Symptoms including persistent or cyclic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea or painful menstruation cramps, deep dyspareunia or pain with deep vaginal penetration, cyclic dyschezia or straining for soft stools, cyclic dysuria or pain with urination, cyclic catamenial symptoms located in other systems such as acne or vomiting.

- Assessment of patient history including infertility, current chronic pelvic pain, or painful periods as an adolescent, previous laparoscopy with diagnosis, painful periods that are not responsive to NSAIDS, and a family history.

- Physical exam physicians assess for nodules in cul de sac, retroverted uterus, mass consistent with endometriosis, visible or obvious external endometrioma. Imaging should be ordered or performed.

- Clinical signs would consist of endometrioma with US, presence of soft markers (sliding sign) this is where the fundus of the uterus is compared to its neighboring structures and can indicate the immobility of those structures, and nodules or masses.

Of course, there are differential diagnosis for endometriosis, and those are symptoms of non-cyclical patterns of pain and bladder/bowel dysfunction that would indicate IBS, UTI, IC/PBS. A history of post-operative nerve entrapment of adhesions. Examination positive for pelvic floor spasm, severe allodynia in vulva and pelvic floor, masses such as fibroids. It is important to note that these other diagnoses can coexist with endometriosis and do not rule out possible endometriosis diagnosis.

Hopefully, diagnosing individuals earlier and possibly at a younger age would limit the disease severity and symptoms. This would allow this population to limit the possibility of central sensitization and pain persistence that can affect so much of daily life. Earlier diagnosis may affect infertility and allow this population to make informed decisions about family and career from a place of empowerment.

Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, Laufer MR, Leyland N, Missmer SA,Singh SS, Taylor HS, "Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action", American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2019), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.039.

Birthing can be an unpredictable process for mothers and babies. With cases of fetal distress, the baby can require rapid delivery. Alternatively, in cases with cephalo-pelvic disproportion, the baby has a larger head, or the mother has a decreased capacity within the pelvis to allow the fetus to travel through the birthing canal. Additionally, the baby may have posterior presentation, colloquially known as “sunny side up” in which the baby’s occipital bone is toward the sacrum. With any of these situations, it is good to know c-sections are an option to safely deliver the child.

Women may also be inclined to try to get a c-section to avoid pelvic complication or tears or because of a history of a severe prior tear. As pelvic therapists, we know that the number of vaginal births and history of vaginal tears increase the risk of urinary incontinence and prolapse. Yet, many therapists are unfamiliar with the effects of c-section and the impact of rehab for diastasis.

Women may also be inclined to try to get a c-section to avoid pelvic complication or tears or because of a history of a severe prior tear. As pelvic therapists, we know that the number of vaginal births and history of vaginal tears increase the risk of urinary incontinence and prolapse. Yet, many therapists are unfamiliar with the effects of c-section and the impact of rehab for diastasis.

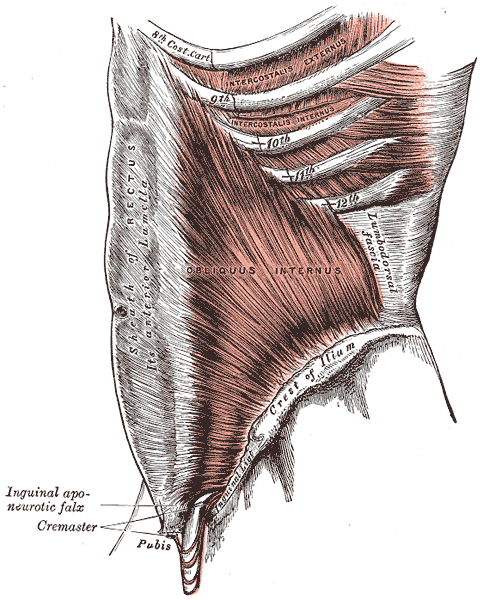

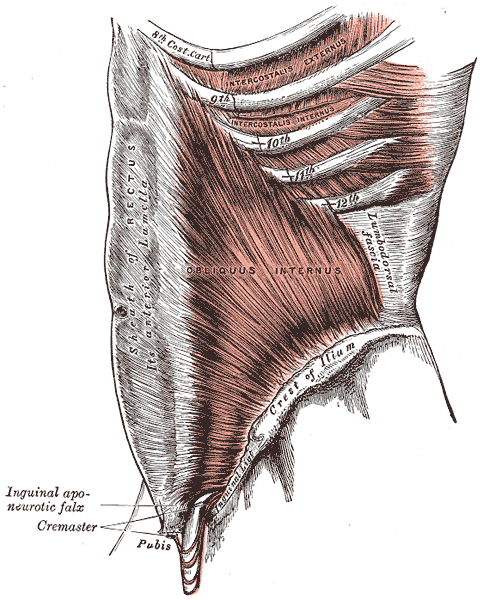

A 2008 dissection study of 37 cadavers studied the path of the ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves. The course of the nerves was compared with standard abdominal surgical incisions, including appendectomy, inguinal, pfannestiel incisions (the latter used in cesarean sections). The study concluded that surgical incisions performed below the level of the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS) carry the risk of injury to the ilioinguinal and iloiohypogastric nerves 1. Another 2005 study reported low transverse fascial incision risk injury to the ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves, and the pain of entrapment of these nerves may benefit from neurectomy in recalcitrant cases.2

Why does injury to the nerves matter? After pregnancy, patients may need rehab and retraining of their abdominal recruitment patterns for diastasis and stability. The ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerves are the innervation for both the transverse abdominus and the obliques below the umbilicus. When we are working to retrain the muscles, certainly neural entrapment or poor firing can greatly impact the success of our intervention as rehab professionals. Interestingly, a study from Turkey showed patients had a significant increase in diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) with a history of 2 cesarean sections and increased parity and recurrent abdominal surgery increase the risk of DRA.2

A fourth study looked at 23 patients with ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment syndrome following transverse lower abdominal incision (such as a c-section). In this study, the diagnostic triad of ilioinguinal and Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment after operation was defined as 1) typical burning or lancinating pain near the incision that radiates to the area supplied by the nerve, 2). Clear evidence of impaired sensory perception of that nerve, and 3) pain relieved by local anaesthetic.4

One of the other symptoms we may see in an area of nerve damage is a small outpouching in the area of decreased innervation on the front lower abdominal wall.

So, what can we do with this information? The good news is that as rehab professionals, we can treat along the fascial pathway of the nerve to release in key areas of entrapment. We can mobilize the nerve directly. Neural tension testing can help us differentiate the nerve in question and we can use neural glides and slides after having freed up the nerve from the area of compression. Then, we can increase the communication of the nerve with the muscles by using specific, localized strengthening and stretch in areas of prior compression. All of these techniques are taught in in our course, Lumbar Nerve Manual Treatment and Assessment. Come join us in San Diego May 3-5, 2019 to learn how to differentially diagnose and treat entrapment of all of the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Okiemy, G., Ele, N., Odzebe, A. S., Chocolat, R., & Massengo, R. (2008). The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. The anatomic bases in preventing postoperative neuropathies after appendectomy, inguinal herniorraphy, caesareans. Le Mali medical, 23(4), 1-4.

Whiteside, J. L., & Barber, M. D. (2005). Ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric neurectomy for management of intractable right lower quadrant pain after cesarean section: a case report. The Journal of reproductive medicine, 50(11), 857-859.

Turan, V., Colluoglu, C., Turkuilmaz, E., & Korucuoglu, U. (2011). Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in the population of young multiparous adults in Turkey. Ginekologia polska, 82(11).

Stulz, P., & Pfeiffer, K. M. (1982). Peripheral nerve injuries resulting from common surgical procedures in the lower portion of the abdomen. Archives of Surgery, 117(3), 324-327.

For many of our patients, chronic pain is a chronic stress. Unfortunately, the resulting ongoing physiological stress reaction can have neurotoxic influences in key brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus, and drive maladaptive neuroplastic changes that may further fuel a chronic pain condition.1 For example, chronic stress generates extensive dendritic spine loss in the prefrontal cortex, hyperactivity in the amygdala, and neurogenesis suppression in the hippocampus.2,3,4 In parallel, patients with chronic pain have been shown to exhibit reduced gray matter in the prefrontal cortex, increased neuronal excitability in the amygdala and reduced hippocampal neurogenesis.5,6,7

These three brain areas have been identified to play an important role in fear learning and memory.8 Modulated by stress hormones and stress-induced neuroplastic changes, stress may:

(a) enhance the memory of the initial pain experience at pain onset

(b) promote the later persistence of the pain memory

(c) impair the memory extinction process and the ability to establish a new memory trace.9

In other words, an ongoing stress reaction, triggered by distressing cognitions and emotions in response to pain or other life circumstances, could reinforce and strengthen the memory of pain. The experience of pain could be generated not by nociceptive activity, but by a well-established memory of pain and inability of the brain to create new associations. Leading researchers in the cortical dynamics of pain at Northwestern University suggest this learning process and persistence of pain memory could be a major influencing mechanism driving chronic pain.9,10

In other words, an ongoing stress reaction, triggered by distressing cognitions and emotions in response to pain or other life circumstances, could reinforce and strengthen the memory of pain. The experience of pain could be generated not by nociceptive activity, but by a well-established memory of pain and inability of the brain to create new associations. Leading researchers in the cortical dynamics of pain at Northwestern University suggest this learning process and persistence of pain memory could be a major influencing mechanism driving chronic pain.9,10

In addition, neurogenesis suppression in the hippocampus is associated with depression, while increased amygdala excitability is associated with anxiety, two mood disorders that frequently accompany and complicate chronic pain conditions.11,12

Why is this important? Appreciating the complex factors that contribute to chronic pain conditions can point to treatment strategies that address these factors.13 For example, strategies that help reduce a patient’s stress reaction, mitigate the experience of fear and anxiety, and/or promote relaxation, positive mood and self-efficacy could conceivably reduce the stress reaction and reverse maladaptive neuroplasticity. While chronic pain is a multifaceted and highly complex condition with no simple answers or one-size-fits-all successful treatment strategy, initial research suggests promise for this approach to modulate cortical structure. In a study of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in the treatment of chronic pain, an 11-week CBT treatment course increased gray matter in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.14

In addition, a systematic review of brain changes in adults who participated in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction identified increased activity, connectivity and volume in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in stressed, anxious and healthy adults.15 Also, the amygdala demonstrated decreased activity and improved functional connectivity with the prefrontal cortex. Although yet to be studied in patients with chronic pain, these neuroplastic changes could potentially promote improved cortical dynamics in our patients.

I am excited to share this model of chronic stress and chronic pain and evidence-based applications of mindfulness to pain treatment in my upcoming course Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment in Arlington, VA August 4 and 5, 2018 and in Seattle, WA November 3 and 4, 2018. Course participants will learn about mindfulness and pain research, practice mindful breathing, body scan and movement and expand their pain treatment tool box with practical strategies to improve pain treatment outcomes. Research examining the application of mindfulness in the treatment of patients at risk of opioid misuse will be included. I hope you will join me!

Vachon-Presseau E. Effects of stress on the corticolimbic system: implications for chronic pain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017; Oct 25. pii: S0278-5846(17)30598-5.

Arnsten AF. Stress signaling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009:10(6):410-422.

Zhang X, Tong G, Guanghao Y, et al. Stress-induced functional alterations in amygdala: implications for neuropsychiatric diseases. Front Neurosci. 2018 May 29;12:367.

Kim EJ, Pellman B, Kim JJ. Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review. Learn Mem. 2015;22(9):411-6.

Fritz HC, McAuley JH, Whittfeld K, et al. Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and anterior insular gray matter: results from a population-based cohort study. J Pain. 2016;17(1):111-8.

Veinante P, Yalcin I, Barrot M. The amygdala between sensation and affect: a role in pain. J Mol Psychiatry. 2013;1(1):9.

Vachon-Presseau E. Roy M, Martel MO, et al. The stress model of chronic pain: evidence from basal cortisol and hippocampal structure and function. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 3):815-27.

Greco JA, Liberzon I. Neuroimaging of fear-associated learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(1):320-334.

Mansour AR, Farmer MA, Baliki. Chronic pain: role of learning and brain plasticity. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2014;32(1):129.

Baliki MN, Apkarian AV. Nociception, pain, negative moods and behavior. Neuron. 2015;87(3):474-491.

Schmaal L, Veltman DJ, van Erp TG, et al. Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from ENIGMA major depressive disorder working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):806-12.

Shin LM, Liberzon I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):169-91.

Greenwald J, Shafritz KM. An integrative neuroscience framework for the treatment of chronic pain: from cellular alterations to behavior. Front Int Neurosci. 2018 May 23;12:18.

Seminowicz DA, Shpaner M, Keaser ML, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy increases prefrontal cortex gray matter in patients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2013;14(2):1573-84.

Gotink RA, Meijboom R, Vernooij, et al. 8-week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction induces brain changes similar to traditional long-term meditation practice – A systematic review. Brain Cogn. 2016;108:32-41.

Exciting news! Carolyn McManus, Herman & Wallace instructor of Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, will be a presenter in programming at the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) World Congress on Pain in to be held in Boston, September 11 - 16. This conference brings together experts from around the globe practicing in multiple disciplines to share new developments in pain research, treatment and education. Participants from over 130 countries are expected to attend. The last time it was held in the U.S. was 2002, so it presents an especially exciting opportunity for those interested in pain to have this international program taking place in the U.S. Carolyn will present a workshop on mindfulness in a Satellite Symposia, Pain, Mind and Movement: Applying Science to the Clinic.

Carolyn has been a leader in bringing mindfulness into healthcare throughout her over-30 year career. She recognized early on in her practice how stress amplified patients’ symptoms and, as she had seen the benefits of mindfulness in her own life, it was a natural progression to integrate mindful principles and practices into her patient care. An instructor for Herman and Wallace since 2014, she has developed two popular courses, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment and Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals, enabling her to share her clinical and research experiences with her colleagues.

Carolyn has been a leader in bringing mindfulness into healthcare throughout her over-30 year career. She recognized early on in her practice how stress amplified patients’ symptoms and, as she had seen the benefits of mindfulness in her own life, it was a natural progression to integrate mindful principles and practices into her patient care. An instructor for Herman and Wallace since 2014, she has developed two popular courses, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment and Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals, enabling her to share her clinical and research experiences with her colleagues.

For many patients, pain is not linearly related to tissue damage and interventions based on structural impairment alone are inadequate to provide full symptom relief. Mindfulness training can offer a key ingredient necessary for a patient to make additional progress in treatment. By learning therapeutic strategies to build body awareness and calm an over-active sympathetic nervous system, patients can mitigate or prevent stress-induced symptom escalation. They can learn to move with trust and confidence rather than fear and hesitation.

A growing body of research in mindfulness-based therapies demonstrates multiples benefits for patients suffering with pain conditions. Research suggests that mindfulness training can be helpful to women preparing for childbirth and patients suffering from fibromyalgia, pelvic pain, IBS and low back pain. In addition, for patients with anxiety, mindfulness training may contribute to reductions in anxiety and in adrenocorticopropic hormone and proinflammatory cytokine release in response to stress. Authors of this study conclude that these large reductions in stress biomarkers provide evidence that mindfulness training may enhance resilience to stress in patients with anxiety disorders.

In addition to her presentation at the IASP World Congress Satellite Symposia, Carolyn will be sharing a more in-depth examination and practice of mindfulness in her upcoming course Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment, August 4 and 5 at Virginia Hospital Center, Arlington VA, and again November 3 and 4 at Pacific Medical Center in Seattle, WA. Please join an internationally-recognized expert for 2 days of innovative training in mindfulness that will both improve your patient outcomes and enhance your own well-being!

Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Chao MT, et al. Benefits of preparing for childbirth with mindfulness training: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017 May 12;17(1):140.

Fox SD, Flynn E, Allen RH. Mindfulness meditation for women with chronic pelvic pain: a pilot study. J Reprod Med.2011;56(3-4):158-62.

Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Paisson O. Therapeutic mechanisms of a mindfulness-based treatment for IBS: effects on visceral sensitivity, catastrophizing and affective processing of pain sensations. J Behav Med. 2012;35(6):591-602.

Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, et al. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(12):1240-9.

Hoge EA, Bui E, Palitz SA, et al. The effect of mindfulness meditation training on biological acute stress responses in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2018;262:328-332.

Coaching Patients to Engage in Positive Activities to Improve Outcomes

Substantial attention has been given to the impact of negative emotional states on persistent pain conditions. The adverse effects of anger, fear, anxiety and depression on pain are well-documented. Complementing this emphasis on negative emotions, Hanssen and colleagues suggest that interventions aimed at cultivating positive emotional states may have a role to play in pain reduction and/or improved well-being in patients, despite pain. They suggest positive affect may promote adaptive function and buffer the adversities of a chronic pain condition.

Hanssen and colleagues propose positive psychology interventions could contribute to improved pain, mood and behavioral measures through various mechanisms. These include the modulation of spinal and supraspinal nociceptive pathways, buffering the stress reaction and reducing stress-induced hyperalgesia, broadening attention, decreasing negative pain-related cognitions, diminishing rigid behavioral responses and promoting behavioral flexibility.

Hanssen and colleagues propose positive psychology interventions could contribute to improved pain, mood and behavioral measures through various mechanisms. These include the modulation of spinal and supraspinal nociceptive pathways, buffering the stress reaction and reducing stress-induced hyperalgesia, broadening attention, decreasing negative pain-related cognitions, diminishing rigid behavioral responses and promoting behavioral flexibility.

In a feasibility trial, 96 patients were randomized to a computer-based positive activity intervention or control condition. The intervention required participants perform at least one positive activity for at least 15 minutes at least 1 day/week for 8 weeks. The positive activity included such tasks as performing good deeds for others, counting blessings, taking delight in life’s momentary wonders and pleasures, writing about best possible future selves, exercising or devoting time to pursuing a meaningful goal. The control group was instructed to be attentive to their surroundings and write about events or activities for at least 15 minutes at least 1 day/week for 8 weeks. Those in the positive activity intervention demonstrated significant improvements in pain intensity, pain interference, pain control, life satisfaction, and depression, and at program completion and 2-month follow-up. Based on these promising results, authors suggest that a full trial of the intervention is warranted.

Rehabilitation professionals often encourage patients with persistent pain conditions to participate in activities they enjoy. This research highlights the importance of this instruction and patient guidelines can include the activities identified in the Muller article. In addition, mindful awareness training may further enhance a patient’s experience as he or she learns to pay close attention to the physical sensations, emotions and thoughts that accompany positive experiences. I look forward to discussing this article as well as sharing the principles and practices of mindfulness in my upcoming course, Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment at Samuel Merritt University, Oakland, CA. Course participants will learn about mindfulness and pain research, practice mindful breathing, body scan and movement and expand their pain treatment tool box with practical strategies to improve pain treatment outcomes. I hope you will join me!

Hanssen MM, Peters ML, Boselie JJ, Meulders A. Can positive affect attenuate (persistent) pain? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(12):80.

Muller R, Gertz KJ, Molton IR, et al. Effects of a tailored positive psychology intervention on well-being and pain in individuals with chronic pain and physical disability: a feasibility trial. Clin J Pain.2016;32(1):32-44.

Advancing Understanding of Nutrition’s Role in…..Well….Everything

Gratitude filled my heart after being able to take part in the pre-conference course sponsored by the APTA Orthopedic Section’s Pain Management Special Interest Group this past February. For two days, participants heard from leaders in the field of progressive pain management with integrative topics including neuroscience, cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, sleep, yoga, and mindfulness to name a few. It’s exciting to witness and participate in the evolution of integrative thinking in physical therapy. When it was my turn to deliver the presentation, I had prepared about nutrition and pain, I could hardly contain my passion. While so much of our pain-related focus is placed on the brain, I realized acutely the stone yet unturned is the involvement of the enteric nervous system (aka the gut) on pain and….well…everything.

Much appreciation is due to those on the forefront of pain sciences for their research, their insight, their tireless work to fill our tool boxes with pain education concepts. Neuroscience has made tremendous leaps and bounds as has corresponding digital media to help explain pain to our patients. One such brilliant 5-minute tool can be found on the Live Active YouTube channel.

What I love about this video is how intelligently (and artistically!) it puts into accessible language some incredibly complex processes. It even mentions lifestyle and nutrition as playing a role in what is commonly referred to as a maladaptive central nervous system.

"Maladaptive central nervous system"

Ok. I’ll admit, I struggle with the implications of this term. However, what doesn’t sit right with me is the concept of chronic or persistent pain being entirely in the brain as though the brain is a static entity. We know the brain to be plastic but often do not identify just how this is so.

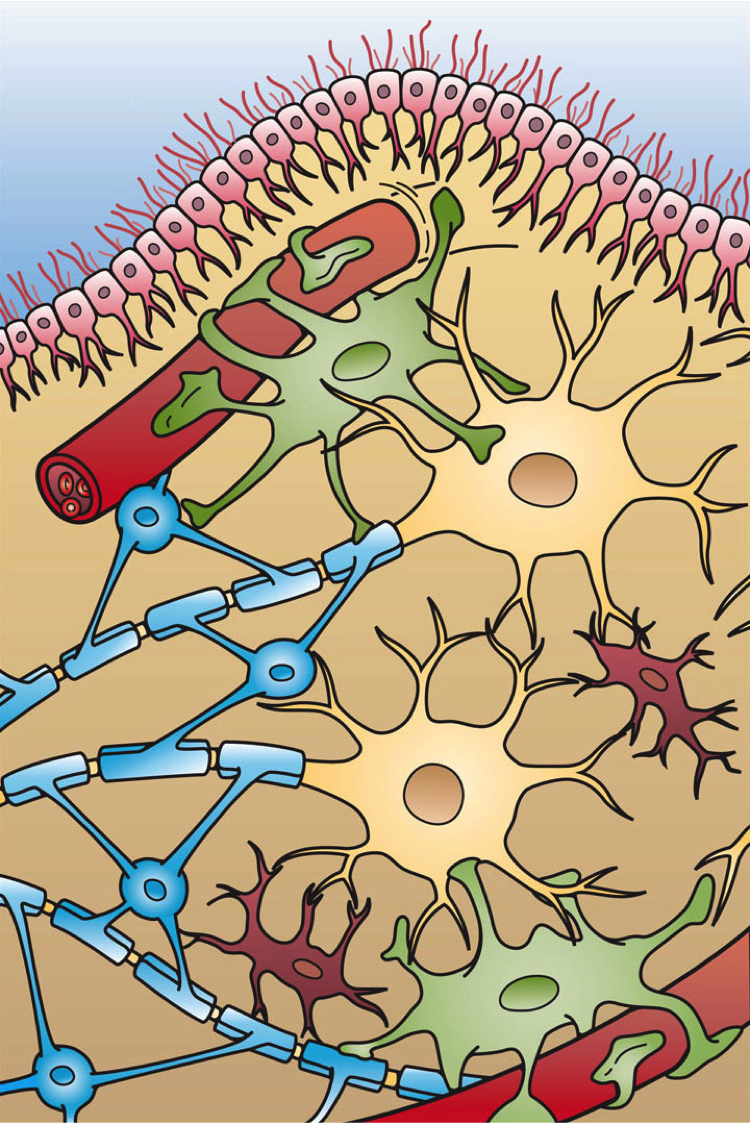

What about the role of our second brain…. the one with 200-600 million neurons that live in that middle part of our body (right next to / inside our pelvis)? Termed the enteric nervous system, this second brain both stores and produces neurotransmittersTurna, et.al., 2016, serves as the scaffolding of interplay between the ENS, SNS, and CNS. This ENS is home to the interface of “bugs, gut, and glial” which are “not only in anatomical proximity, but also influence and regulate each other…interconnected for mutual homeostasis.”Lerner, et.al., 2017 In fact, part of this process then directly impacts the brain. “Healthy brain function and modulation are dependent upon the microbiota’s [gut bugs] activity of the vagus nerve.”Turna, et.al., 2016. Further, “by direct routes or indirectly, through the gut mucosal system and its local immune system, microbial factors, cytokines, and gut hormones find their ways to the brain, thus impacting cognition, emotion, mood, stress resilience, recovery, appetite, metabolic balance, interoception and PAIN.”Lerner, et.al., 2017

What about the role of our second brain…. the one with 200-600 million neurons that live in that middle part of our body (right next to / inside our pelvis)? Termed the enteric nervous system, this second brain both stores and produces neurotransmittersTurna, et.al., 2016, serves as the scaffolding of interplay between the ENS, SNS, and CNS. This ENS is home to the interface of “bugs, gut, and glial” which are “not only in anatomical proximity, but also influence and regulate each other…interconnected for mutual homeostasis.”Lerner, et.al., 2017 In fact, part of this process then directly impacts the brain. “Healthy brain function and modulation are dependent upon the microbiota’s [gut bugs] activity of the vagus nerve.”Turna, et.al., 2016. Further, “by direct routes or indirectly, through the gut mucosal system and its local immune system, microbial factors, cytokines, and gut hormones find their ways to the brain, thus impacting cognition, emotion, mood, stress resilience, recovery, appetite, metabolic balance, interoception and PAIN.”Lerner, et.al., 2017

So, by process of logic, it requires little convincing to conclude that the food we eat or fail to eat directly impacts the health or dysfunction of this magnificently orchestrated system. One that directly and profoundly impacts our brain, our body, our being. And it’s a concept that our patients, our clients, ourselves, know in our gut to be true.

And it’s thanks to all the hard work of those who have come before us that we can share in the advancing understanding for the benefit of thousands who need your help, expertise and guidance. Please join me for Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist. The next course will be in Springfield, MO on June 23-24, 2018. Vital and clarifying information awaits you!

Live Active. (2013, Jan) Understanding Pain in less than 5 minutes, and what to do about it! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_3phB93rvI Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Lerner, A., Neidhofer, S., & Matthias, T. (2017). The Gut Microbiome Feelings of the Brain: A Perspective for Non-Microbiologists. Microorganisms, 5(4). doi:10.3390/microorganisms5040066

Turna, J., Grosman Kaplan, K., Anglin, R., & Van Ameringen, M. (2016). "What's Bugging the Gut in Ocd?" a Review of the Gut Microbiome in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Depress Anxiety, 33(3), 171-178. doi:10.1002/da.22454