Dr. Steve Dischiavi, MPT, DPT, SCS, ATC, COMT, a Herman & Wallace faculty member, recently co-authored a peer reviewed manuscript which reviewed hip focused exercise programs. Dr. Dischiavi currently teaches a hip related course in the Herman & Wallace curriculum titled “Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis: Dynamic Integration of the Myofascial Sling Systems.”

"An evidence based review of hip focused neuromuscular exercise interventions to address dynamic lower extremity valgus", published in the Journal of Sports Medicine, presents evidence related to current hip focused interventions within the physical therapy profession. We know that there has been an enormous increase in the amount of hip related diagnoses and surgeries, and this calls for better knowledge from the clinicians on how to manage these particular hip related pathologies. The review finds that insufficient research has been done "to identify and understand the mechanistic relationship between optimized biomechanics during sports and hip-focused neuromuscular exercise interventions... improved strength does not always result in changes to important biomechanical variables, and improved biomechanics in sports-related tasks does not necessarily equal improved biomechanical variables in performance of the sport itself".

"An evidence based review of hip focused neuromuscular exercise interventions to address dynamic lower extremity valgus", published in the Journal of Sports Medicine, presents evidence related to current hip focused interventions within the physical therapy profession. We know that there has been an enormous increase in the amount of hip related diagnoses and surgeries, and this calls for better knowledge from the clinicians on how to manage these particular hip related pathologies. The review finds that insufficient research has been done "to identify and understand the mechanistic relationship between optimized biomechanics during sports and hip-focused neuromuscular exercise interventions... improved strength does not always result in changes to important biomechanical variables, and improved biomechanics in sports-related tasks does not necessarily equal improved biomechanical variables in performance of the sport itself".

Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis is an opportunity to explore manual movement therapy with a skilled researcher and practitioner. Dr. Dischiavi has woven a very creative and innovative philosophy to help clinicians design more comprehensive hip focused therapeutic interventions. His in-depth knowledge of the evidence has allowed him to create a program that will challenge clinicians in new ways to look at the hip, pelvis, and lower extremity and how the kinetic chain can be influenced by approaching it using a new lens.

Participants of his course will learn new ways to activate and strengthen groups of pelvic muscles that will benefit all patients from pelvic health clients, to professional athletes, to your elderly population. “All patients have the same bones, muscles, and gravitational pulls acting on them, its how they use these systems that varies significantly. A philosophical science can be generated, but the art is in implementing that science.”

Participants in the Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis course have enjoyed being challenged to look at the hip and pelvis in a different way. Practitioners will leave the course having learned a whole new way to develop and implement therapeutic exercises which are a different approach from the single plane non-weight bearing exercises that are traditionally prescribed to patients.

There are many courses and philosophies on how to screen for lower extremity injuries and how to evaluate movement dysfunction. What is really lacking for clinicians are options for therapeutic exercises which target the hip and pelvis in a relevant and functional manner. Most hip focused programs currently emphasize single plane movements and are dominated with concentric focused exercise. Dr. Dischiavi’s focus is targeted directly at human movement emphasizing tri-planar movements that are primarily eccentric in nature, recognizing that this is how the human body functions.

Come to the Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis: Manual Movement Therapy and the Myofascial Sling System in Seattle this June, or in Boston this August!

The following post comes to us from Dee Hartmann, PT, DPT who is the author and instructor of Vulvodynia: Assessment and Treatment. To learn evaluation and treatment techniques for vulvar pain, join Dee in in Houston, TX this March 12-13. Early registration pricing expires soon!

I recently heard a young, vivacious urologist present treatment options for overactive bladder to a group of nursing professionals (SUNA). To my delight as the only PT in the audience, I was pleased that physical therapy was her first line of treatment for this difficult population of chronic pelvic pain patients. As a women’s health PT, we know that chronic vulvar pain suffers experience many of the same dysfunctions, including pelvic floor muscle over-activity.

I recently heard a young, vivacious urologist present treatment options for overactive bladder to a group of nursing professionals (SUNA). To my delight as the only PT in the audience, I was pleased that physical therapy was her first line of treatment for this difficult population of chronic pelvic pain patients. As a women’s health PT, we know that chronic vulvar pain suffers experience many of the same dysfunctions, including pelvic floor muscle over-activity.

The physician’s presentation included two very emphatic statements—“physical therapy always hurts” and “no one in this group of patients should ever do Kegel exercises”. She went on to explain that anyone with pelvic floor muscle over activity should only be taught to relax; that “if they were seeing a practitioner who was telling them to do Kegels, they needed to find another PT”. As she’s not a PT, I challenged her on her second comment. I was too annoyed to address the first.

I appreciate that, as a urologist, she may not know that we learned some time ago that rest for chronic muscle tension, like chronic low back, has been proven ineffective[1]. Rather, research suggests that increased mobility and strengthening prove more effective in the long term to decrease pain by restoring normal muscle function. As pelvic floor muscles are voluntary, striated muscles, it only makes sense that the same findings apply. Those who oppose active pelvic floor muscle active exercise suggest that the over-active state of the pelvic floor muscles causes vulvar pain. I agree. However, simply relaxing dysfunctional pelvic floor muscles and expecting them to work effectively seems a bit short-sighted. Normal pelvic floor muscle function is integral to efficient core stability as well as sphincteric control, pelvic visceral support, and sexual function. Why not begin rehab for these ladies with an active exercise program, directed at renewing pelvic floor muscle motor control, with resulting decreased introital pain, improved function (sphincteric , supportive, and sexual), and improved core support?

As for the urologist’s first statement, mark me down as totally opposed. My professional experience suggests the need to replicate familiar vulvar pain and then find abnormal physical findings in the trunk, hips, viscera, and pelvis that are contributory. Rather than utilizing any treatment that causes additional pain, addressing associated abnormal findings that immediately decrease pelvic floor muscle resting tone and palpated vulvar pain, seems much more productive.

[1] Waddell G. "Simple low back pain: rest or active exercise?" Ann Rheum Dis 1993;52:317.

The following post comes to us from long-time faculty member Dawn Sandalcidi PT, RCMT, BCB-PMD! Dawn is a figurehead in the world of pediatric pelvic floor, she teaches Pediatric Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (available three times in 2016) and she just completed the 2nd edition of the Pediatric Pelvic Floor Manual!! Today Dawn is sharing her insights an urotherapy for pediatric patients.

If you read any papers on pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction you will often come across the word "urotherapy". It is by definition a conservative based management based program used to treat lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction using a variety of health care professionals including the physician, Physical Therapists, Occupational Therapists and Registered Nurses.

If you read any papers on pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction you will often come across the word "urotherapy". It is by definition a conservative based management based program used to treat lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction using a variety of health care professionals including the physician, Physical Therapists, Occupational Therapists and Registered Nurses.

Basic urotherapy includes education on the anatomy and function of the LUT, behavior modifications including fluid intake, timed or scheduled voids, toilet postures and avoidance of holding maneuvers, diet, bladder irritants and constipation. This needs to be tailored to the patients’ needs. For example a child with an underactive bladder needs to learn how to sense urge and listen to their body and a child who postpones a void needs to be on a voiding schedule. Urotherapy alone can be helpful however a recent study demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in uroflow, pelvic floor muscle electromyography activity during a void, urinary urgency, daytime wetting and reduced post void residual (PVR) in those patients who received pelvic floor muscle training as compared to Urotherapy alone. This is great news for all of us who are qualified to teach pelvic floor muscle exercise!

The International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) has now expanded the definition of Urotherapy to include Specific Urotherapy. This includes biofeedback of the pelvic floor muscles by a trained therapist who is able to teach the child how to alter pelvic floor muscle activity specifically to void. It also includes neuromodulation for many types of lower urinary tract dysfunction but most commonly with overactive bladder and neurogenic bladder. Cognitive behavioral therapy and psychotherapy are always important to assess (see blog post on psychological effects of bowel and bladder dysfunction).

It truly does take a village to help this kiddos and I am honored to be a team player!

To learn more about pediatric incontinence and pelvic floor rehabilitation, join Dawn Sandalcidi at one of her courses this year! Details at the following links:

Pediatric Incontinence - Augusta, GA - Apr 16, 2016 - Apr 17, 2016

Pediatric Incontinence - Torrance, CA - Jun 11, 2016 - Jun 12, 2016

Pediatric Incontinence - Waterford, CT - Sep 17, 2016 - Sep 18, 2016

Chang SJ, Laecke EV, Bauer, SB, von Gontard A, Bagli,D, Bower WF,Renson C, Kawauchi A, Yang SS-D. Treatment of daytime urinary incontinence: a standardization document from the international children's continence society. Neurourol Urodyn 2015;Oct 16. doi:10.1002/nau.22911

Ladi Seyedian SS, Sharifi-Rad L, Ebadi M, Kajbafzadeh AM. Combined functional pelvic floor muscle exercise with swiss ball and Urotherapy for management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr.2014 Oct;173(10):1347-53. I.J.N. Koppen, A. von Gontard, J. Chase, C.S. Cooper, C.S. Rittig, S.B. Bauer, Y. Homsy, S.S. Yang, M.A. Benninga. Management of functional nonretentive fecal incontinence in children: recommendations from the International Children’s Continence Society. J of Ped Urol (2015)

Koppen IJ, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Dinning PG, Yacob D, Levitt MA, Benninga MA. .Childhood constipation: finally something is moving! Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Oct 14:1-15.

The following post comes to us from Herman & Wallace faculty member Tina Allen, PT, BCB-PMD who teaches many courses with the institute. Tina's new course, Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist, will be debuting this October in San Diego, CA.

As a physical therapist who has been treating pelvic floor dysfunction for 20 years, the patient who still impacts me the most happens to be the second patient I ever treated. The patient was a 22 year old woman who, before she even was referred to me for pelvic pain, had already seen 14 medical providers and experienced 10 procedures including a hysterectomy. She had been told by more than half of her providers that this pain was “in her head”, that “she needed counseling”, and that there was no reason for her pain. With 4 years of clinical experience at the time, I felt discouraged and wondered how I was going to help her. Then I remembered that no one else could look at her muscles and biomechanics like a PT could.

As a physical therapist who has been treating pelvic floor dysfunction for 20 years, the patient who still impacts me the most happens to be the second patient I ever treated. The patient was a 22 year old woman who, before she even was referred to me for pelvic pain, had already seen 14 medical providers and experienced 10 procedures including a hysterectomy. She had been told by more than half of her providers that this pain was “in her head”, that “she needed counseling”, and that there was no reason for her pain. With 4 years of clinical experience at the time, I felt discouraged and wondered how I was going to help her. Then I remembered that no one else could look at her muscles and biomechanics like a PT could.

I started out by educating her about the muscles “down there”, observed how she moved with her daily tasks and then I completed her seemingly first ever muscular evaluation of the perineum. After 6 sessions of down training, muscle reeducation, manual therapy, strengthening of her hip and teaching her how to self mobilize the tissues of the perineum, she reported a pain level of 3/10- the lowest her pain level had been since she was 13 years old! Of course, she asked why it took so long for her to be referred to PT.

While this felt like an extreme story to me at the time, I now know that this is still the reality for many of the clients that we work with as pelvic floor PT’s. This experience set up the aspiration for me to have medical residents in my clinic with me to teach them what PT can do for patients and so that the residents can better evaluate their patients. As pointed out in research in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education, residents in obstetrics and gynecology do not feel adequately prepared to manage the care of women who have chronic pelvic painWitzeman & Kopfman, 2014. Specifically, residents reported negative attitudes towards patients with pelvic pain, and feelings of not having enough time to address their patients’ needs. When asked about how they preferred to learn more about care of patients with pelvic pain, the residents were interested in one-on-one clinical teaching as well as use of diagnostic algorithms. At this point in time I have medical residents with me at least 2 days per month. It’s a start!

So, what does a typical day look like with a 1st year OB/GYN resident in your clinic?

First, I always do my best to let my clients know in advance that a physician will be with me that day. The patient can always decline but most patients are accommodating. I have found that most of our patients want to advocate for themselves and others by having that physician with us in our session to teach them about how PT has helped them.

I spend the first 30 minutes when the resident arrives by bringing out the pelvic floor muscle model and explaining the function of all the muscles and how those muscles impact function. I also describe how this function is impacted by fascia, the muscles of the trunk, biomechanics and mind/body connections. Then we start seeing patients. After I have reviewed the patient’s current status, we begin our session. The patient is asked to give the resident their history and medical history. It’s been wonderful to watch my patients teach the residents and to hear the patients be able to explain their condition including procedures and functional restrictions.

The residents will then be instructed to palpate and learn about restricted tissues, observe how the patient uses their pelvic floor muscles, core, trunk and legs with their daily tasks. The residents have the opportunity to observe how we progress the patient’s self care in therapy.

While the session may start with the resident feeling frustrated that they are not able to be seeing their own patients or preparing for their tests, it usually ends with the resident asking when they can come back to the clinic to learn more about what we do and how we can help patients.

I urge all of us to reach out and invite physicians, PA’s, ARNP’s, midwives, naturopaths and nurses into our clinics to learn. With a little advanced planning we can get patients the help they need as soon as possible.

Witzeman, K. A., & Kopfman, J. E. (2014). Obstetrics-Gynecology Resident Attitudes and Perceptions About Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Targeted Needs Assessment to Aid Curriculum Development. Journal of graduate medical education, 6(1), 39-43.

Herman & Wallace faculty member Eric Dinkins, PT, MS, OCS, Cert. MT, MCTA teaches the Manual Therapy for the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex: Mobilization with Movement and Laser-Guided Feedback for Core Stabilization course for Herman & Wallace. He is one of only 13 practitioners in America credentialed to teach the Mulligan Concept of Manual Therapy, and is a published author. Join him in Arlington, VA on August 20-21, 2016 to learn new joint mobilization, evaluation, and treatment skills.

Much research has been published regarding evaluation and diagnosis of the Sacroiliac Joint (SIJ). Low back pain and pelvic girdle pain is a common complaint with patients in all clinic settings. Laslett (Manual Therapy 2005) gave our profession valuable insight into categorizing a cluster of tests to try to ensure Physical Therapists and Chiropractors know if the SI joint is a pain source of our patients. We now also have several articles reaffirming the validity of the Active Straight Leg Raise (ASLR) and Stork testing for SIJ dysfunction (Manual Therapy 2008; JBMR 2012; PT 2007). However, after talking with clinicians who attend my Mobilization with Movement classes, as well as many colleagues in the outpatient orthopedic setting, there is a definitive lack of understanding how to use this information to translate over to successful treatment. This is understandable considering there have been several articles published regarding the poor validity and consistency between clinicians regarding palpation skills and bony landmarks in the lumbar spine and pelvis (ex: Manual Therapy 2012). But perhaps the fault is not in the clinician proficiency, but rather in the nature that we are attempting to diagnose an SIJ dysfunction?

If you were to consult with experts in body kinematics, gait analysis, and biomechanics regarding the true movement of the SIJ, there will be many different answers depending on the action that they were describing. Particularly when it comes to dysfunction. Disagreements abound when describing conditions such as “upslips”, “inflares”, etc and virtually all back their arguments with clinical anecdotal success rates. These arguments often leave clinicians with inconsistencies in treatment and increased failures.

If you were to consult with experts in body kinematics, gait analysis, and biomechanics regarding the true movement of the SIJ, there will be many different answers depending on the action that they were describing. Particularly when it comes to dysfunction. Disagreements abound when describing conditions such as “upslips”, “inflares”, etc and virtually all back their arguments with clinical anecdotal success rates. These arguments often leave clinicians with inconsistencies in treatment and increased failures.

This blog is meant to be a persuasive argument for using function-improving or pain- eliminating techniques for diagnosis and treatment of SIJ dysfunction. The logic of this approach is often misunderstood. But if applied correctly, satisfies most theory surrounding the SIJ, and provides immediate feedback for knowing how to resolve the condition and what you are treating.

We have pain provocative testing that is most commonly used in attempting to diagnose a SIJ dysfunction. However, after interpreting these tests, the clinician is still left without a true diagnosis as to the nature of what is happening at this joint to cause pain or dysfunction. This is likened to the "painful shoulder" or "low back pain" prescription we see. The error rates, even in the cluster, still leaves room for inaccurate assessment and therefore potential misguided treatment. Lumbar facet, musculature, hip capsule imbalance, are just some examples that can produce false positives on the typical SIJ tests that are used in clinic. Therefore, it is necessary to understand that pain provocative testing ONLY tells us that pain is coming from that structure that is being tested. And NOT that it is “THE” source of the dysfunction.

Now consider using function-improving or pain-eliminating techniques for your evaluation. The ALSR test, as an example, function improving special test. Compression applied to various aspects of the pelvis or supporting musculature yield a positive finding if the SLR is now easier if the force is applied. Combing this information with the faulty kinetic testing of the Stork and/or leg pull test to determine the involved side yield an immediate feedback for both the clinician and the patient as to what forces are needed to correct the dysfunction that is limiting the functional activity and restore normal motion. Treatment would then be applied by creating a force on the innominate, sacrum, or both and would then be maintained throughout the movement and can be considered a form of active exercise (manual assisted active exercise). If retesting of the affected motion yields a sustained improvement, the accurate diagnosis has now been made. And surely this diagnosis would be upheld if the patient returned at a later date to demonstrate no regression occurred.

If the force applied to the pelvis was directed toward posterior rotation at the innominate and/or an anterior rotation at the sacrum, and the affected motion cleared without pain or limited motion, it would be confirmed that these forces were necessary to correct the dysfunction on the involved side regardless of the "ambiguous diagnosis' including the potential of a previously held thought of an anterior rotation of the pelvis (making the argument of what actually happened at the pelvis mute). This may have been achieved through altering inputs viewed as a potential "threat" by the system, or mechanics stresses, etc. Regardless, if manual correction of this condition was applied and the dysfunction was correction through re-creating this without pain, one would conclude that this dysfunction was the primary eitiology of the symptoms. If the symptoms returned or the functional test was not normalized, an easy conclusion would then be that despite manual correction eliminating pain during the activity, this correction was not addressing the source of the dysfunction. And therefore the clinician should consider treatment elsewhere.

In essence, the body is capable of directing what it needs in order to return to a normal functioning homeostasis…without the application of pain. Now this pain-eliminating testing becomes your assessment, treatment and potentially your home exercise program!

To conclude, it is my suggestion to all manual based physiotherapists and chiropractors to strongly consider pain-eliminating techniques for both evaluation and treatment in their practice.

Did I mention yet that your patient already voted for that….?

Laslett, M, et al. "Diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Pain: Validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests" Manual Therapy 10 (2005) 207-218

M. de Groot, et al. "The active straight leg raising test (ASLR) in pregnant women: Differences in muscle activity and force between patients and health subjects" Manual Therapy 13 (2008) 68-74

Hungerford, B, et al. "Evaluation of the Ability of Physical Therapists to Palpate Intrapelvic Motion with the Stork Test on the Support Side" Phys Ther. 2007 Jul;87(7):879-87.

O'Surrivan PB, Beales DJ. "Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders—Part 1: A mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework" Man Ther. 2007 May;12(2):86-97.

Arab AM, Abdollahi I, Joghataei MT, Golafshani Z, Kazemnejad A. "Inter- and intra-examiner reliability of single and composites of selected motion palpation and pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint" Man Ther. 2009 Apr;14(2):213-21. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2008.02.004. Epub 2008 Mar 25.

Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute faculty member, Ginger Garner PT, L/ATC, PYT, will be giving 2 lectures at this year’s annual Montreal International Symposium for Therapeutic Yoga, or MISTY for short, in Montreal, Quebec. The first is a 2-hour lecture titled, Vocal Liberation, and the second is a 4-hour lecture titled, Hip Preservation: Yoga Reconsidered, Visit http://www.homyogaevents.com to learn more. Read below as Ginger shares why the voice is a linking science.

The Voice as a Linking Science for Clinical and Business Efficacy

Your voice can be the key to your success. Forbes magazine’s #3 habit in an article, Five Habits of Highly Effective Communicators, is “Find your own voice.” London’s think tank Tomorrow’s Company declares in a recent report on efficacy in business leadership, “Having a voice really matters for employees today.” The director of the Involvement and Participation Association (IPA) and vice-chair of the London-based MadLeod Review on employee engagement says, “Voice is extremely important because there are many changing business concepts and one of the essential ones is trust. Our voice is one of the things we really need to change old management paradigms and build trust in an organization.”

Your voice can be the key to your success. Forbes magazine’s #3 habit in an article, Five Habits of Highly Effective Communicators, is “Find your own voice.” London’s think tank Tomorrow’s Company declares in a recent report on efficacy in business leadership, “Having a voice really matters for employees today.” The director of the Involvement and Participation Association (IPA) and vice-chair of the London-based MadLeod Review on employee engagement says, “Voice is extremely important because there are many changing business concepts and one of the essential ones is trust. Our voice is one of the things we really need to change old management paradigms and build trust in an organization.”

If you are an instructor, teacher, educator, therapist, or all four, having a voice is synonymous with having a job. You can’t do your job without a voice. And yet, we don’t spend much time thinking about vocal physiology, much less how to maintain and even improve it.

The most powerful change agent or therapeutic modality you have - is your voice. Yet, the voice is often overlooked as a therapeutic tool. Think of how important it is for someone giving a TED talk to have good vocal quality, for example. Now consider how important it is for others, like you, who may have to speak for hours on end each day. The vocal folds must be cared for just like we attend to the mind and body during postural yoga practice or movement therapy.

What were the other findings of the report?

- Voice is the foundation of sustainable business success. It increases employee engagement, enables effective decision-making and drives innovation.

- Finding your voice involves both cultural and structural pursuit. First, we need to be culturally competent and sensitive. Only then can we provide the right process through which our voice can be heard.

The power of the voice cannot be ignored, particularly for those who have allergies, respiratory issues, or struggle to make a powerful impact or to establish themselves as an effective team member or thought leader. Oftentimes, the voice is the single variable that holds us back from making the success we are seeking in our work. US News World and Report states,

“Whether you are an aspiring leader or in a support role, developing your communication skills can impact your success. First, let’s take a look at the complexities of communication. It's more than the words you use. It's how and when you choose to share information. It's your body language and the tone and quality of your voice.”

Psychology Today and National Public Radio have recently reported on the relationship between vocal quality and job success and effectiveness. Both agree that speech rate, tone of voice, facial expression, and diction have a great deal of power to make or break effective communication. If tone doesn’t match facial expression, for example, neural dissonance occurs, which erodes trust, increase skepticism, and cooperation.1 In fact, warm vocal tone is a sign of transformational leadership, which generates “more satisfaction, commitment, and cooperation between team members”.2 Changing pitch increases therapeutic potential and improves the chances of your being understood by colleagues, especially when diction is congruent with emotion.1 Additionally, training mindfulness during public speaking can improve prefrontal cortex activity, which allows for improved social awareness, mood-regulation, decision-making, and empathy.4 Vocal awareness and training can slow your pace of speaking, which is shown to deepen others’ respect for you and simultaneously calm anxiety, traits which are bridge-building and healing for all relationships, business and personal.

About MISTY

MISTY is a not-for-profit organization and event dedicated to teaching others about therapeutic yoga.

Ginger’s workshop, “Vocal Liberation,” will introduce techniques for developing and preserving the voice, including projection, quality, longevity, and therapeutic impact through fusion of nada yoga and ENT physiology, which Ginger has developed over her career in public speaking and vocal performance. Want to learn about therapeutic yoga at MISTY? There’s still time to join Ginger and a host of other talented speakers and therapists. Learn more and register at http://www.homyogaevents.com.

Use of affective prosody by young and older adults. Dupuis K, Pichora-Fuller MK. Psychol Aging. 2010 Mar;25(1):16-29.

Leadership = Communication? The Relations of Leaders' Communication Styles with Leadership Styles, Knowledge Sharing and Leadership Outcomes. de Vries RE, Bakker-Pieper A, Oostenveld W. J Bus Psychol. 2010 Sep;25(3):367-380.

Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Tang YY, Ma Y, Wang J, Fan Y, Feng S, Lu Q, Yu Q, Sui D, Rothbart MK, Fan M, Posner MI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Oct 23;104(43):17152-6.

Faculty member, Ginger Garner PT, L/ATC, PYT will be giving 2 lectures at this year’s annual Montreal International Symposium for Therapeutic Yoga, or MISTY for short, in Montreal, Quebec. The first is a 2-hour lecture titled, Vocal Liberation, and the second is a 4-hour lecture titled, Hip Preservation: Yoga Reconsidered, Visit http://www.homyogaevents.com to learn more.

Yoga is, unarguably, a popular contemplative science, enjoying 36.7 million practitioners in the US alone, up from 20.4 million in 2012.1 A 16 billion dollar industry, yoga is one of the most widely utilized methods of complementary and integrative medicine in America today. In 2008, the editor of Yoga Journal declared “yoga as medicine” as the next great wave. That was right in the middle of the Great Recession, when the last thing on the collective healthcare industry’s mind was yoga.

Yoga is, unarguably, a popular contemplative science, enjoying 36.7 million practitioners in the US alone, up from 20.4 million in 2012.1 A 16 billion dollar industry, yoga is one of the most widely utilized methods of complementary and integrative medicine in America today. In 2008, the editor of Yoga Journal declared “yoga as medicine” as the next great wave. That was right in the middle of the Great Recession, when the last thing on the collective healthcare industry’s mind was yoga.

What happened during the same time frame as the interest in yoga surged?

Our expanded knowledge of hip anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology exploded onto the medical scene, providing more information than ever about how to address, preserve, and otherwise attend to the hip joint. Prior to this new age of research, the hip was relegated to a joint worthy of no more than a tendonitis, bursitis, or osteoarthritis diagnosis. A person was simply a hip replacement candidate or not. There was no other option once a hip joint had prematurely degenerated. Now, that has all changed, thanks to technological advances in diagnostic testing and investigation.

Yet, the worlds of hip preservation and rehabilitation and yoga have yet to join hands. Many of my patients and colleagues have suffered from unnecessary hip injuries, from labral tears, all types of impingement, and compounding secondary diagnoses such as torn hamstrings, sports hernias, gluteal tendinopathy, to pelvic pain, all due to yoga practice. Some suffered injuries in yoga class during a single traumatic injury, and some injuries were drawn out over years of accumulated microinjury to capsuloligamentous, bony, or cartilaginous structures.

Hip labral injuries (HLI) have vastly increased over the last 10 years, perhaps making HLI the newest orthopaedic diagnosis of the 21st century. This discovery also makes surgical and conservative management of HLI uncharted territory. Conservative therapy includes nonsurgical and post-surgical rehabilitation, and since the average time from injury to diagnosis is 2.5 years, there are many people with hip, pelvic, back, or sacroiliac joint pain that have undiagnosed hip labral tears.

I should make myself quite clear, however. I am not out to demonize yoga or fear-monger the practice of yoga or how it may wreck a person’s body (to use recently controversial language).

My purpose is two-fold: To clarify 1) “what” and “how” yoga can be a safe, effective form or physical therapy and rehabilitation for the hip and pelvis, as well as to 2) underscore the areas where yoga posture practice should be evolved to prevent injury.

To that end, I have written and will be presenting a new 4-hour workshop entitled, Hip Preservation: Yoga Reconsidered, at the Montreal International Symposium on Therapeutic Yoga (MISTY) this weekend in Canada. The lecture is relevant for yoga teachers, yoga enthusiasts, yoga therapists, and health care professionals who are interested in learning how to prevent hip injury in yoga practice.

The workshop will introduce identification of imbalances that could contribute to HLI, as well as understand the common mistakes made in yoga practice that could increase HLI or hip impingement. Understanding the pain patterns that surround HLI are also critical to safe and therapeutic yoga practice and will be discussed. Discussion of structure, function, ability and “dis”ability of the hip, including their major substrates, will help identify the “red flags” in yoga practice, identifying high risk populations and those who need postural modification(s) and/or outside referral to physical therapy.

I am looking forward to instructing a high energy, action-packed hands-on learning session at MISTY on March 19-20, along with my presenting a 2-hour lecture on maximizing public speaking impact through Vocal Liberation: The Voice as Therapy.

- The Voice as a Linking Science for Clinical and Business Efficacy

- Hip Preservation: Yoga Reconsidered

- Ginger’s lecture overview - Montreal International Symposium for Therapeutic Yoga

Want to learn more?

Bring Ginger’s 16 hour continuing education course, Differential Diagnosis for Hip Labral Injuries to your facility in 2017 through Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Yoga in America 2016 Survey. Yoga Alliance and Yoga Journal. January 2016.

Faculty member Lila Bartkowski- Abbate PT, DPT, MS, OCS, WCS, PRPC teaches the Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction and the Pelvic Floor course for Herman & Wallace. Join her in Tampa on April 2-3, or one of the other two events currently open for registration.

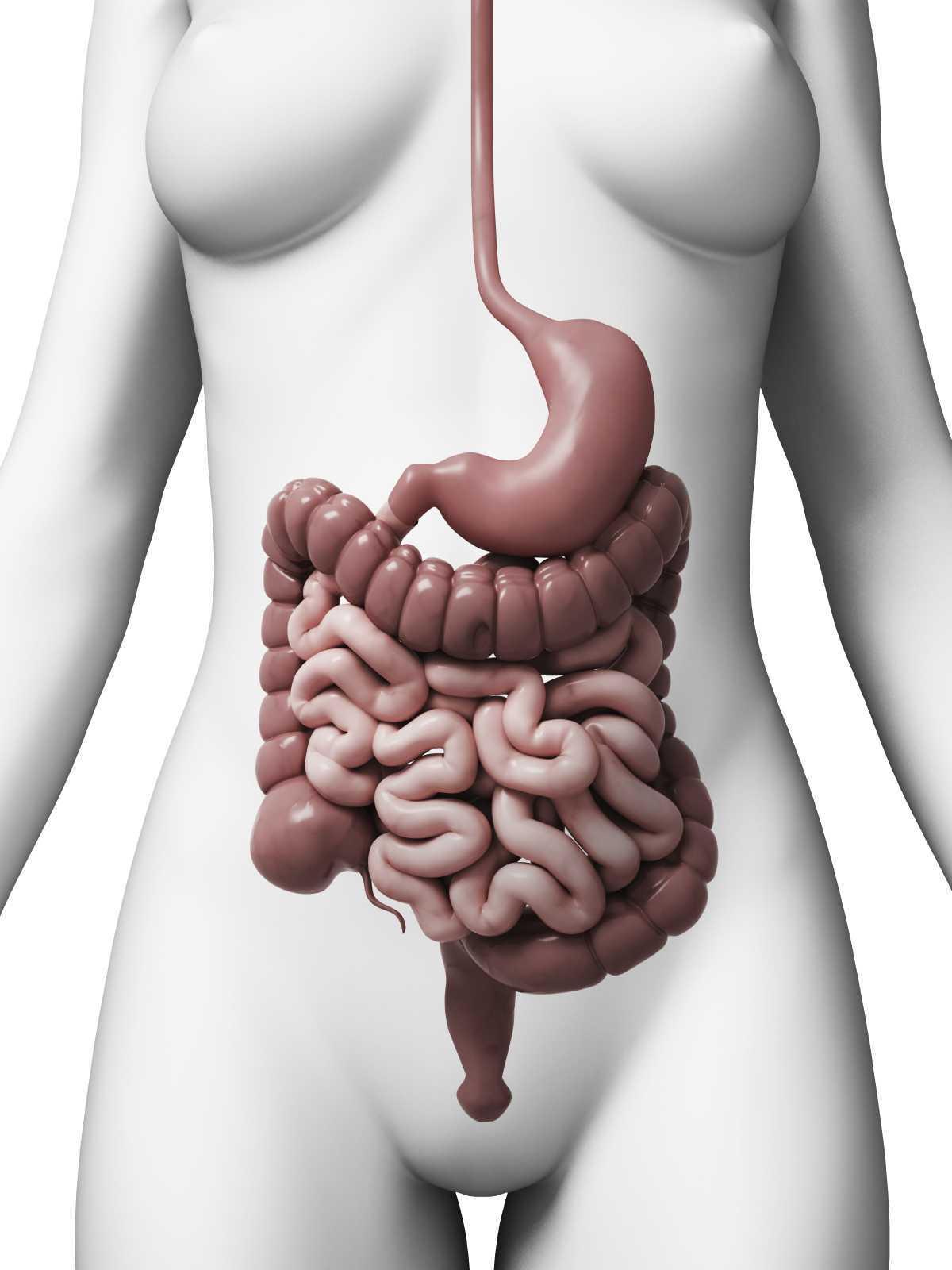

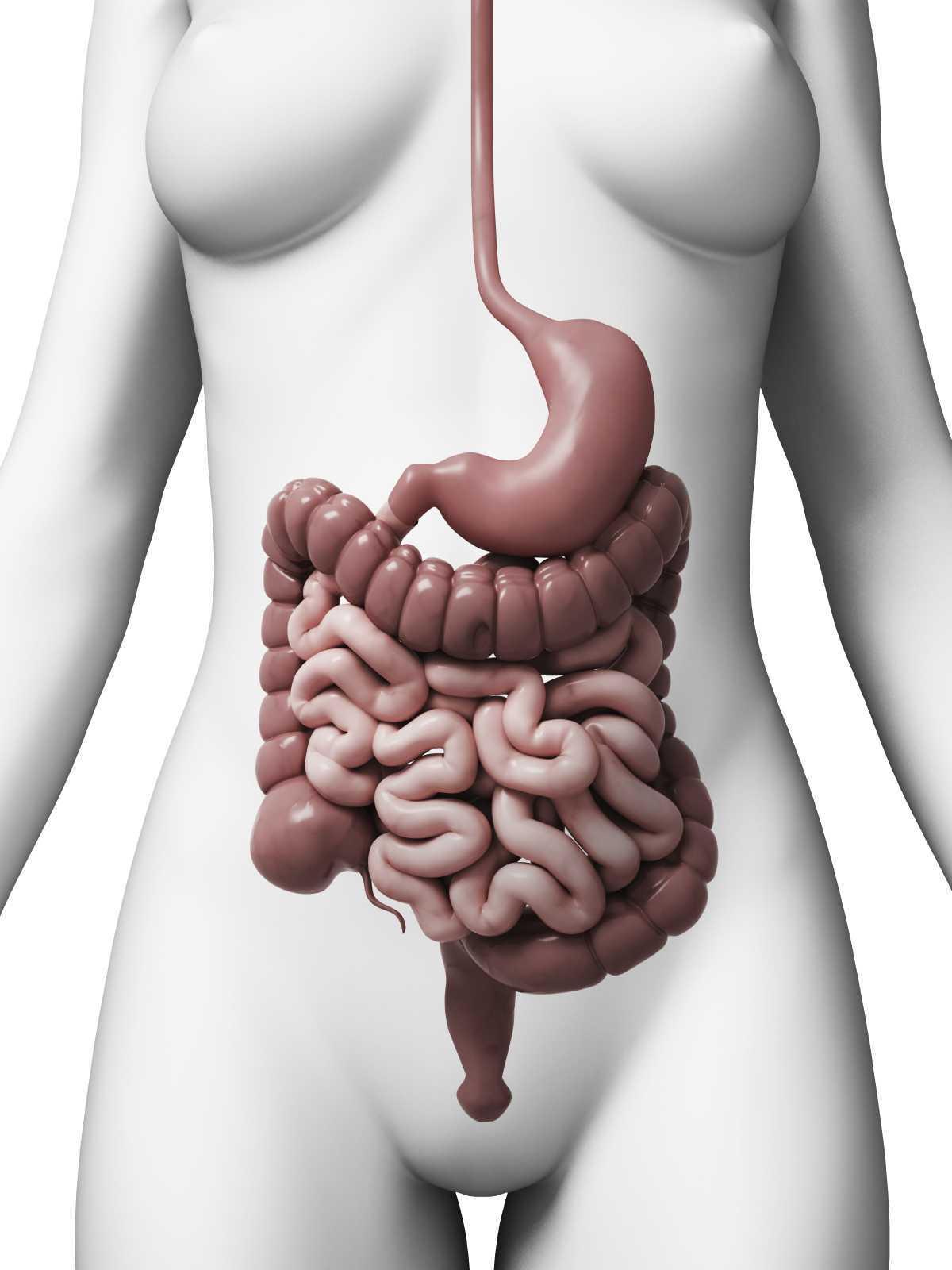

Constipation, an often under reported health issue, afflicts about 30% of Americans. ¹ The diagnosis of chronic constipation may seem like a simple concept, however the etiology of chronic constipation presents itself in many different forms. Dyssynergic defecation is one of many factors that can lead to a presentation of chronic constipation in a patient. Dyssynergic defecation or “paradoxical contraction” occurs when the muscles of the abdominals, puborectalis sling, and external anal sphincter function inappropriately while attempting a bowel movement. ² The lack of coordination of these muscles results in a contraction versus a lengthening of the pelvic floor muscles with baring down. Dyssynergic defecation is different than a structural issue such as a rectocele or hemorrhoids causing the inability to pass stool effectively or constipation due to slow colon transit time or pathological disease. Making the diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation by symptoms alone is often not reliable secondary to overlap of similar symptoms with chronic constipation due to factors such as a structural issue, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or irritable bowel disease (IBD). The diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation can be difficult and is often made through physiologic testing such as balloon expulsion testing or MRI with defecography. ² However, physical therapists can often manually feel that a paradoxical contraction is happening when asking a patient to bare down on evaluation.

Constipation, an often under reported health issue, afflicts about 30% of Americans. ¹ The diagnosis of chronic constipation may seem like a simple concept, however the etiology of chronic constipation presents itself in many different forms. Dyssynergic defecation is one of many factors that can lead to a presentation of chronic constipation in a patient. Dyssynergic defecation or “paradoxical contraction” occurs when the muscles of the abdominals, puborectalis sling, and external anal sphincter function inappropriately while attempting a bowel movement. ² The lack of coordination of these muscles results in a contraction versus a lengthening of the pelvic floor muscles with baring down. Dyssynergic defecation is different than a structural issue such as a rectocele or hemorrhoids causing the inability to pass stool effectively or constipation due to slow colon transit time or pathological disease. Making the diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation by symptoms alone is often not reliable secondary to overlap of similar symptoms with chronic constipation due to factors such as a structural issue, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or irritable bowel disease (IBD). The diagnosis of dyssynergic defecation can be difficult and is often made through physiologic testing such as balloon expulsion testing or MRI with defecography. ² However, physical therapists can often manually feel that a paradoxical contraction is happening when asking a patient to bare down on evaluation.

Patients with dyssynergic defecation may present to pelvic floor physical therapy with complaints of: ¹ ²

- Abdominal symptoms such as bloating, pain, and cramping

- Poor response to laxatives and fiber supplementation that does not fully resolve their issue

- Have had testing for anatomical or neurological abnormalities with no significant findings

- Complaints of concomitant pelvic pain due to over activity of the pelvic floor muscles

Physical Therapists specializing in pelvic floor rehab can be a valuable part of the medical team with treating these patients. Biofeedback training by physical therapists has been shown to decrease anorectal related constipation symptoms and abdominal symptoms in patients with dyssynergic defecation. In a sample of 77 patients with dyssynergic defecation, physical therapists provided biofeedback training for 6-8 weeks that included manual and verbal feedback, surface EMG, exercises using a rectal catheter, rectal ballooning to improve rectal sensory abnormalities, ultrasound, pelvic floor and abdominal massage, electrical stimulation if needed, and core strengthening and stretching to improve the patients’ maladaptive habits while attempting to pass a bowel movement. Significant decreases were seen on all three domains (abdominal, rectal, and stool) on the PAC-SYM (Patient Assessment of Constipation) questionnaire post biofeedback training. ² It is noteworthy that 74% of these patients presented to the clinic with complaints of abdominal symptoms such as bloating, pain, discomfort, and cramping.

Knowing how to effectively treat these patients and ask the right questions is valuable in the scheme of pelvic floor rehab secondary to overlapping symptoms of different causes of chronic constipation. Physical therapists are able to provide these patients with conservative treatment that can effectively improve or eliminate their problem, recognize dyssynergic defecation as a possible differential diagnosis, and refer to the appropriate medical professional for further testing. Recognizing and treating dyssynergic defecation is something physical therapists will learn how to become effective at in the upcoming Herman and Wallace Course: Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction & the Pelvic Floor April 2-3 in Tampa, FL and October 8-9 in Fairfield, CA.

1. Sahin M, Dogan I, Cengiz M et al. (2015). The impact of anorectal biofeedback therapy on quality of life of patients with dyssynergic defecation. Turk J Gastroenterol. 26(2):140-144

2. Baker J, Eswaran S, Saad R, et al. (2015). Abdominal symptoms are common and benefit from biofeedback therapy in patients with dyssynergic defecation. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 30(6)e105. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.3

The following comes to us from Carolyn McManus, PT, MS, MA, our resident expert in the power of mindfulness and it's applications to rehabilitation. Carolyn was recently featured in a video from the Journal of the American Medical Association for her contributions to a newly published research article. Join Carolyn at her course, Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment: A Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain on May 14th and 15th in California's Bay Area!

Neuroimaging studies show that cortical and sub-cortical brain regions associated with cognitive and emotional processing connect directly with descending pain modulating circuits arising in the brainstem. As diminished nociceptive inhibition by descending pain modulation is a likely contributing factor to the persistence of pain, these cortical and sub-cortical connections to relevant brainstem regions provide a means by which maladaptive cognitive and emotional processing can contribute to the persistence of pain1. It is possible that strategies to help patients self-regulate cognitions and emotions could promote pain reduction through restoring the balance between excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms of the descending pain modulatory system.

Neuroimaging studies show that cortical and sub-cortical brain regions associated with cognitive and emotional processing connect directly with descending pain modulating circuits arising in the brainstem. As diminished nociceptive inhibition by descending pain modulation is a likely contributing factor to the persistence of pain, these cortical and sub-cortical connections to relevant brainstem regions provide a means by which maladaptive cognitive and emotional processing can contribute to the persistence of pain1. It is possible that strategies to help patients self-regulate cognitions and emotions could promote pain reduction through restoring the balance between excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms of the descending pain modulatory system.

To be mindful is to rest the mind in the present moment with stability and acceptance and without additional cognitive or emotional elaboration. Mindful body awareness is a central component. Training in mindful awareness has been shown to improve attention regulation, emotional processing and body awareness and contribute to reduced pain intensity, catastrophizing, depression and anxiety2,3,4,5. Training in mindfulness has also been shown to modulate brain activity in areas associated with body awareness and pain processing6,7. It is possible that the adaptive modulation of cortical and sub-cortical areas engaged with mindful cognitive, emotional and physical self-regulation could contribute to reducing pain through improving the balance between excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms of the descending pain modulatory system.

One of my patients reflected the clinical benefits of mindfulness training when he said, “I needed to learn how to not freak out when my exercises or daily activities increased my pain. Focusing my mind on the present moment was enormously helpful. I would tell myself, “Breathe. Just be here. Calm down.” By breathing and relaxing I could take control of how I was reacting and I immediately saw a difference. My pain did not increase out of control.”

I am thrilled to be sharing my 30+ year experience in mindfulness and patient care in my upcoming course through Herman and Wallace.

1. Ossipov M, Morimura K, Porreca F. Descending pain modulation and chronification of pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2014;8(2):143-151.

2. Holzel BK, Lazar SW, Guard T, et al. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Science. 2011;6: 537–559.

3. Reiner K, Tibi L, Lipsitz JD. Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature. Pain Med. 2013 Feb;14(2):230-42.

4. Lakhan SE, Schofield KL. Mindfulness-based therapies in the treatment of somatization disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013 Aug 26;8(8):e71834.

5. Schutze , Slater H, O’Sullivan P, et al. Mindfulness-based functional therapy: A preliminary open trial of an integrated model of care for people with persistent low back pain. Front Psychol. 2014 Aug 4;5:839.

6. Zeidan F, Martucci KT, Kraft RA, et al. Brain mechanisms supporting modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. J Neurosci. 2011 Apr 6;31(14):5540-8.

7. Nakata H, Sakamoto K, Kakigi R. Meditation reduces pain-related activity in the anterior cingulated cortex, insula, secondary somatosensory cortex and thalamus. Front psychol. 2014;5:1489.

Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, BCB-PMD, PRPC is a published researcher and practitioner who has worked in the realms of brain injury, lymphedema, and oncology. Now she's leading the charge to encourage rehabilitation practitioners to utilize ultrasound diagnostic imaging with their patients, and you can learn these techniques in her Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging - Women's Health and Orthopedic Topics course taking place May 1 - 3 in Dayton, OH. We've partnered with SonoSite to make the best ultrasound equipment available for participants in this course.

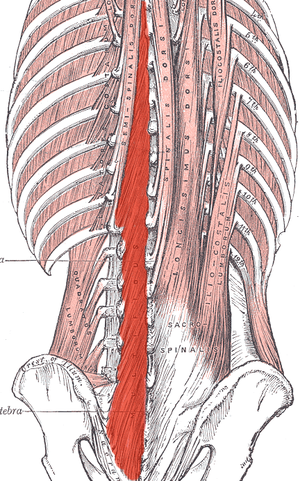

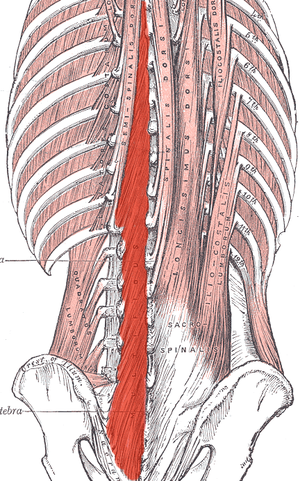

Most of us are treating patients who have back pain of some nature, and we know the importance of the local stabilizing muscles including the transverse abdominis, the lumbar multifidus, and the pelvic floor muscles. These muscles work together to provide tension and create a corset of stability throughout the trunk. A common goal is to rehabilitate these muscles in order to restore motor control and strength, but the muscle depth can make them difficult to assess and palpate.

Most of us are treating patients who have back pain of some nature, and we know the importance of the local stabilizing muscles including the transverse abdominis, the lumbar multifidus, and the pelvic floor muscles. These muscles work together to provide tension and create a corset of stability throughout the trunk. A common goal is to rehabilitate these muscles in order to restore motor control and strength, but the muscle depth can make them difficult to assess and palpate.

I recently read a study that is looking at the development of a test to identify lumbar multifidus function. Herbert et al. found promising results when looking at this “multifidus lift test” for inter-rater reliability and concurrent validity to identify dysfunction in the multifidus. They compared the results of this test with real-time ultrasound imaging of the lumbar multifidus. Inter-rater reliability was excellent and free from errors of bias and prevalence. Concurrent validity was demonstrated through its relationship with the reference standard results at L4-L5, but not so much for L5-S1. This preliminary research supports the reliability and validity of the multifidus lift test to assess lumbar multifidus function at some spinal levels. If this test could be further validated for other spinal levels it would be very beneficial for therapists who are using a specific stabilization program to treat patients.

Until this test is further developed and validated how can therapists know for sure that their patient is truly activating their multifidus? Ultrasound imaging is the answer! Ultrasound imaging gives therapists real-time feedback for whether a patient is able to correctly activate a muscle or not. It is also a wonderful biofeedback tool for patients who are trying to rehabilitate these muscles. Getting your hands on an ultrasound machine can be tough, but therapists who work in a hospital system may have an easier time than you'd think. I have worked with many therapists to help them get access to ultrasound units through “hand me down” units from imaging or labor and delivery departments. I also have helped private practice therapists set up a working relationship with a physician who has an ultrasound in their office. Thinking outside of the box can allow clinicians to gain access to ultrasound units without having to spend a lot of money. Join me in Dayton Ohio this May to hear more about how ultrasound imaging can improve your practice and allow you to incorporate a specific stabilization program into your toolbox.

Herbert JJ, Koppenhaver SL, Teyhen DS, Walker BF, Fritz JM. The evaluation of lumbar multifidus muscle function via palpation: reliability and validity of a new clinical test. Spine J. 2015; 15(6): 1196-202.