Help others by helping ourselves

As pelvic rehabilitation practitioners, we have all been there, looking ahead to see what patients are on our schedules and recognizing that several will require immense energy from us… all afternoon! Then we prepare ourselves, hoping we have enough stamina to get through, and do a good job to help meet the needs of these patients. Then we still have to go home, spend time with our families, do chores, run errands, and have endless endurance. This can happen day after day. Naturally, as rehabilitation practitioners, we are helpers and problems solvers. However, this requires that we work in emotionally demanding situations. Often in healthcare, we experience burnout. We endure prolonged stress and/or frustration resulting in exhaustion of physical and/or emotional strength and lack of motivation. Do we have any vitality left for ourselves and our loved ones? How can we help ourselves do a good job with our patients, but to also honor our own needs for our energy?

How do we as health care practitioners’ prevent burnout?

How do we as health care practitioners’ prevent burnout?

Ever hear of “mindfulness” ... I am being facetious. The last several years we have been hearing a lot about “mindfulness” (behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based stress reduction) and its positive effects in helping patients cope with chronic pain conditions. Mindfulness is defined as “the practice of maintaining a nonjudgmental state of heightened or complete awareness of one's thoughts, emotions, or experiences on a moment-to-moment basis,” according to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary. One can practice mindfulness in many forms. Examples of mindfulness-based practice include, body scans, progressive relaxation, meditation, or mindful movement. Many of us pelvic rehabilitation providers teach our patients with pelvic pain some form of mindfulness in clinic, at home, or both, to help them holistically manage their pain. Whether it is as simple as diaphragmatic breathing, awareness of toileting schedules/behavior, or actual guided practices for their home exercise program, we are teaching mindfulness behavioral therapy daily.

Why don’t we practice what we preach?

As working professionals, we are stressed, tired, our schedules too full, and we feel pain too, right? Mindfulness behavioral therapy interventions are often used in health care to manage pain, reduce stress, and control anxiety. Isn’t the goal of using such interventions to improve health, wellness, and quality of life? Mindfulness training for healthcare providers can reduce burnout by decreasing emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and increasing sense of personal accomplishment. Additionally, it can improve mood, empathy for patients, and communication.1 All of these improvements, leads to improved patient satisfaction.

Let’s take what we teach our patients every day and start applying it to ourselves. An informal way to integrate mindfulness is by building it into your day. Such as when washing hands in between patients, or before you walk into the room to greet the patient. However, sometimes we have a need for a tangible strategy to combat stress and the desire to be guided by an expert with this strategy.2 I think one of the easiest ways to begin practicing mindfulness is to try a meditation application (app) on a smart phone or home computer. Meditation is one of the most common or popular ways to practice mindfulness and is often a nice starting point to try meditation for yourself or to suggest to a motivated patient. Many popular guided meditation apps include Headspace, Insight Timer, and Calm, just to name a few. Generally, these guided meditation apps have free versions and paid upgrades. Challenge yourself to complete a 10-minute guided meditation app, daily, for three weeks, and see how you feel. It takes three weeks to make a new habit. Hopefully, guided meditation will be a new habit to help you be present with your patients and improve your awareness and energy. After all, how can we help others heal, if we can’t help ourselves?

To learn more about ways, you as a professional can help yourself or your patients with meditation, consider attending Meditation for Patients and Providers.

1)Krasner, M.S., Epstein, R.M., Beckman, H., Suchman, A.L., Chapman, B., Mooney C.J., et al. (2009). Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA 302(12):1284–93.

2)Willgens, A. M., Craig, S., DeLuca, M., DeSanto, C., Forenza, A., Kenton, T., ... & Yakimec, G. (2016). Physical Therapists' Perceptions of Mindfulness for Stress Reduction: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 30(2).

When I bring up the topic of pelvic floor dysfunction in athletes, stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is usually the first aspect of pelvic health that springs to mind – and rightly so, as professional sport is one of the risk factors for stress urinary incontinence Poswiata et al 2014. The majority of studies show that the average prevalence of urinary incontinence across all sports is 50%, with SUI being the most common lower urinary tract symptom. Athletes are constantly subject to repeated sudden & considerable rises in intra-abdominal pressure: e.g. heel striking, jumping, landing, dismounting and racquet loading.

What’s less often discussed is the topic of gastrointestinal dysfunction in athletes. Anal incontinence in athletes is not well documented, although a study from Vitton et al in 2011 found a higher prevalence than in age matched controls (conversely a study by Bo & Braekken in 2007 found no incidence). More recently, Nygaard reported earlier this year (2016) that young women participating in high-intensity activity are more likely to report anal incontinence than less active women.

A presentation by Colleen Fitzgerald, MD at the American Urogynecologic Society meeting in 2014 highlighted the multifaceted nature of pelvic floor dysfunction in female athletes, specifically in this case, triathletes. The study found that one in three female triathletes suffers from a pelvic floor disorder such as urinary incontinence, bowel incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. One in four had one component of the "female athlete triad", a condition characterized by decreased energy, menstrual irregularities and abnormal bone density from excessive exercise and inadequate nutrition. Researchers surveyed 311 women for this study with a median age range of 35 – 44. These women were involved with triathlete groups and most (82 percent) were training for a triathlon at the time of the survey. On average, survey participants ran 3.7 days a week, biked 2.9 days a week and swam 2.4 days a week.

Of those who reported pelvic floor disorder symptoms, 16% had urgency urinary incontinence, 37.4% had stress urinary incontinence, 28% had bowel incontinence and 5% had pelvic organ prolapse. Training mileage and intensity were not associated with pelvic floor disorder symptoms. 22% of those surveyed screened positive for disordered eating, 24% had menstrual irregularities and 29% demonstrated abnormal bone strength. With direct access becoming a reality for many of us, we must acknowledge the need for specific questioning when it comes to pelvic health issues, as well as the ability to recognise signs and symptoms of the female athlete triad in our patients.

Want to learn more about pelvic health for athletes? Join me in beautiful Arlington this November 5-6 at The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor!

J Hum Kinet. 2014 Dec 9; 44: 91–96 Published online 2014 Dec 30. doi:10.2478/hukin-2014-0114 PMCID: PMC4327384. Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Elite Female Endurance Athlete Anna Poświata, Teresa Socha and Józef Opara1

J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011 May;20(5):757-63. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2454. Epub 2011 Apr 18. Impact of high-level sport practice on anal incontinence in a healthy young female population. Vitton V, Baumstarck-Barrau K, Brardjanian S, Caballe I, Bouvier M, Grimaud JC.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214(2):164-71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.067. Epub 2015 Sep 6. Physical activity and the pelvic floor. Nygaard IE, Shaw JM.

Our understanding of treating pelvic pain keeps growing as a profession. We have so many manual therapies such as visceral manipulation, strain counter strain, and positional release adding dimension to our treatment strategies for shortened and painful tissues. Pharmacologic interventions such as botox, valium, and antidepressants are becoming more popular and researched in the literature. We are beginning to work more collaboratively with vulvar dermatologists, urogynecologists, OB’s, family practitioners, urologists, and pain specialists.

Pelvic rehab providers are in a unique position of being able to offer more time with each patient and to see our patients for several visits. Frequently we are the ones being told stories about how a particular condition is really affecting our patient’s life and the emotional struggles around that. We are often the one who gets a clear picture of our patient’s emotional and mental disposition. A rehab provider may realize that a patient seems to exhibit mental patterns in their treatment. It can be anxiety from how the condition is changing their life, difficulty relaxing into a treatment, poor or shallow breathing patterns, frequently telling themselves they will never get better, or being able to perceive their body only as a source of pain or suffering, losing the subtlety of the other sensations within the body. Yet, aside from contacting a physician, who may offer a medication with side effects, or referring to a counselor or psychologist, our options and training may be limited. Patients may be resistant to seeing a mental health counselor, and we have to be careful to stay in our scope.

Pelvic rehab providers are in a unique position of being able to offer more time with each patient and to see our patients for several visits. Frequently we are the ones being told stories about how a particular condition is really affecting our patient’s life and the emotional struggles around that. We are often the one who gets a clear picture of our patient’s emotional and mental disposition. A rehab provider may realize that a patient seems to exhibit mental patterns in their treatment. It can be anxiety from how the condition is changing their life, difficulty relaxing into a treatment, poor or shallow breathing patterns, frequently telling themselves they will never get better, or being able to perceive their body only as a source of pain or suffering, losing the subtlety of the other sensations within the body. Yet, aside from contacting a physician, who may offer a medication with side effects, or referring to a counselor or psychologist, our options and training may be limited. Patients may be resistant to seeing a mental health counselor, and we have to be careful to stay in our scope.

Research is showing us that meditation as an intervention can be very helpful in addressing these chronic pain issues.

In a study in the Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 22 women with chronic pelvic pain were enrolled in an 8 week mindfulness meditation course. Twelve out of 22 enrolled subjects completed the program and had significant improvement in daily maximum pain scores, physical function, mental health, and social function. The mindfulness scores improved significantly in all measures (p < 0.01).

The questions have arisen, if meditation alters opiod pathways, how can it be administered safely with prescription medications. However in a 2016 study in the journal of neuroscience, it was concluded that meditation-based pain relief does not require endogenous opioids.” Therefore, the treatment of chronic pain may be more effective with meditation due to a lack of cross-tolerance with opiate-based medications.” “The risks of chronic therapy are significant and may outweigh any potential benefits”, according the the journal of American Family Medicine. Meditation training can be a tool to help our patients manage their pain without risk of long term opiod use.

In the two day course, Meditation for Patients and Providers, participants will learn several different meditation and mindfulness techniques they can use for patients with different dispositions, and to tailor the most appropriate approach to specific patients. The aim of the course is to be able to work meditation into a treatment and a home program that is best suited for your patient. The course also covers self care, preventing provider burn out and ways to be more mentally quiet as a provider seeking to give optimal care with appropriate boundaries.

Fox, S. D., Flynn, E., & Allen, R. H. (2010). Mindfulness meditation for women with chronic pelvic pain: a pilot study. The Journal of reproductive medicine, 56(3-4), 158-162.

LEMBKE, A., HUMPHREYS, K., & NEWMARK, J. (2016). Weighing the Risks and Benefits of Chronic Opioid Therapy. American Family Physician,93(12).

Zeidan, F., Adler-Neal, A. L., Wells, R. E., Stagnaro, E., May, L. M., Eisenach, J. C., ... & Coghill, R. C. (2016). Mindfulness-Meditation-Based Pain Relief Is Not Mediated by Endogenous Opioids. The Journal of Neuroscience, 36(11), 3391-3397.

Urinary incontinence (UI) can be problematic for both men and women, however, is more prevalent in women. Incontinence can contribute to poor quality of life for multiple reasons including psychological distress from stigma, isolation, and failure to seek treatment. Patients enduring incontinence often have chronic fear of leakage in public and anxiety about their condition. There are two main types of urinary leakage, stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urge urinary incontinence (UUI).

SUI is involuntary loss of urine with physical exertion such as coughing, sneezing, and laughing. UUI is a form of incontinence in which there is a sudden and strong need to urinate, and leakage occurs, commonly referred to as “overactive bladder”. Currently, SUI is treated effectively with physical therapy and/or surgery. Due to underlying etiology, UUI however, can be more difficult to treat than SUI. Often, physical therapy consisting of pelvic floor muscle training can help, however, women with UUI may require behavioral retraining and techniques to relax and suppress bladder urgency symptoms. Commonly, UUI is treated with medication. Unfortunately, medications can have multiple adverse effects and tend to have decreasing efficacy over time. Therefore, there is a need for additional modes of treatment for patients suffering from UUI other than mainstream medications.

An interesting article published in The Journal of Alternative and Complimentary Medicine reviews the potential benefits of yoga to improve the quality of life in women with UUI. The article details proposed concepts to support yoga as a biobehavioral approach for self-management and stress reduction for patients suffering with UUI. The article proposes that inflammation contributes to UUI symptoms and that yoga can help to reduce inflammation.

Surfacing evidence indicates that inflammation localized to the bladder, as well as low-grade systemic inflammation, can contribute to symptoms of UUI. Research shows that women with UUI have higher levels of serum C-reactive protein (a marker of inflammation), as well as increased levels of inflammatory biomarkers (such as interleukin-6). Additionally, when compared to asymptomatic women and women with urgency without incontinence, patients with UUI have low-grade systemic inflammation. It is hypothesized that the inflammation sensitizes bladder afferent nerves through recruitment of lower threshold and typically silent C fiber afferents (instead of normally recruited, higher threshold A-delta fibers, that respond to stretch of the bladder wall and mediate bladder fullness and normal micturition reflexes). Therefore, reducing activation threshold for bladder sensory afferents and a lower volume threshold for voiding, leading to the UUI.

How can yoga help?

Yoga can reduce levels of inflammatory mediators. According to the article, recent research has shown that yoga can reduce inflammatory biomarkers (such as interleukin -6) and C-reactive protein. Decreasing inflammatory mediators within the bladder may reduce sensitivity of C fiber afferents and restore a more normalized bladder sensory nerve threshold.

Studies suggest that women with UUI have an imbalance of their autonomic nervous system. The posture, breathing, and meditation completed with yoga practice may improve autonomic nervous system balance by reducing sympathetic activity (“fight or flight”) and increasing parasympathetic activity (“rest and digest”).

The discussed article highlights yoga as a logical, self-management treatment option for women with UUI symptoms. Yoga can help to manage inflammatory symptoms that directly contribute to UUI by reducing inflammation and restoring autonomic nervous system balance. Additionally, regular yoga practice can improve general well-being, breathing patterns, and positive thinking, which can reduce overall stress. Yoga provides general physical exercise that improves muscle tone, flexibility, and proprioception. Yoga can also help improve pelvic floor muscle coordination and strength which can be helpful for UUI. Yoga seems to provide many benefits that could be helpful for a patient with UUI.

In summary, UI remains a common medical problem, in particular, in women. While SUI is effectively treated with both conservative physical therapy and surgery, long-term prescribed medication remains the treatment modality of choice for UUI. However, increasing evidence, including that described in this article, suggests that alternative conservative approaches, such as yoga and exercise, may serve as a valuable adjunct to traditional medical therapy.

Tenfelde, S., & Janusek, L. W. (2014). Yoga: a biobehavioral approach to reduce symptom distress in women with urge urinary incontinence. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20(10), 737-742.

A diagnosis of breast cancer means many different things to many different people. Regardless, receiving this diagnosis means some sort of treatment will likely follow. The types of treatment and outcomes are largely dependent on individual patient scenarios, however, one thing is for certain: A patient’s life will be forever changed after having received this diagnosis.

Historically, comprehensive care for a patient with breast cancer has focused on treatment and prevention. However, more and more women are surviving breast cancer every year. Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to survivorship. Once someone has survived cancer, comprehensive, quality care should obviously focus on preventing recurrence, however, it may also include guidance and counseling on maintaining a healthy lifestyle and addressing physical and psychosocial changes.

A very recent 2016 article published in the Annals of Surgical Oncology discusses the subject of survivorship in breast cancer patients. This article suggests that the key to achieving successful outcomes for management of a breast cancer survivor is a multidisciplinary approach to help these survivors deal with the physical and psychosocial sequela resulting from their diagnosis.

A very recent 2016 article published in the Annals of Surgical Oncology discusses the subject of survivorship in breast cancer patients. This article suggests that the key to achieving successful outcomes for management of a breast cancer survivor is a multidisciplinary approach to help these survivors deal with the physical and psychosocial sequela resulting from their diagnosis.

As a pelvic rehabilitation provider, this is a very thought-provoking article as it outlines several areas in which I feel breast cancer survivors could benefit from physical therapy. A pelvic rehabilitation provider can be a valuable part of the multidisciplinary team that helps manage a breast cancer survivor towards positive and meaningful outcomes, ultimately enhancing their quality of life. The following are some areas addressed in the article in which a breast cancer survivor may need assistance to improve and support a meaningful quality of life.

Sexuality: According to this article, studies show treatment for breast cancer is associated with significant decrease in sexual interest, desire, arousal, and difficulty achieving orgasm and/or lack of sexual pleasure. Additionally, patients can also report pain with intercourse (dyspareunia) and/or vaginal dryness, which can lead to sexual dysfunction. Physical therapy can help by providing education on normal sexual response and lubricants, as well as help with tissue healing. Therapeutic techniques include exercise and manual treatments to areas that may be damaged from surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Additionally, exercise has been shown to improve self-image. Poor body image has been linked to sexual dysfunction following breast surgery (depending on the type “breast sparing techniques” versus mastectomy). This includes only some of the ways a physical therapist can help improve sexual dysfunction.

Lymphedema: According to the article, 30-70% of breast cancer patients experience lymphedema after treatment. Physical therapy can play an important role in the control and/or reduction of lymphedema. A physical therapist can provide helpful education, exercise, weight control, and, if needed, manual techniques and compression garments and bandaging.

Teachable moments after cancer diagnosis: A teachable moment is when you identify and seize an opportunity to educate your patient. After a life altering event or illness, people are more accepting of advice and change of lifestyle. As healthcare providers, we can utilize this time to help our patients improve outcomes by modifying their behavior. The cited article states there is clear evidence that physical activity decreases incidence and recurrence.There is additional evidence to show controlling weight and maintaining a normal body mass index (BMI) improves breast cancer survivor outcomes. A physical therapist can help a breast cancer survivor to develop a guided and progressive home exercise program to help them maintain normal BMI and participate in regular physical activity safely and regularly.

The discussed article, “Breast Cancer Survivorship: Why, What and When?”, sheds light on many areas of physical and psychosocial challenges that patients surviving breast cancer may deal with. This article also advocates that a multidisciplinary approach yields the greatest outcomes. I suggest that physical therapy can be a valuable part of the team when creating patient care plans for breast cancer survivors.

To learn more about breast cancer and outcomes based treatments, consider attending "Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient! The next course is taking place in Stockton, CA this September 24-25.

Gass, J., Dupree, B., Pruthi, S., Radford, D., Wapnir, I., Antoszewska, R., ... & Johnson, N. (2016). Breast Cancer Survivorship: Why, What and When?. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 1-6.

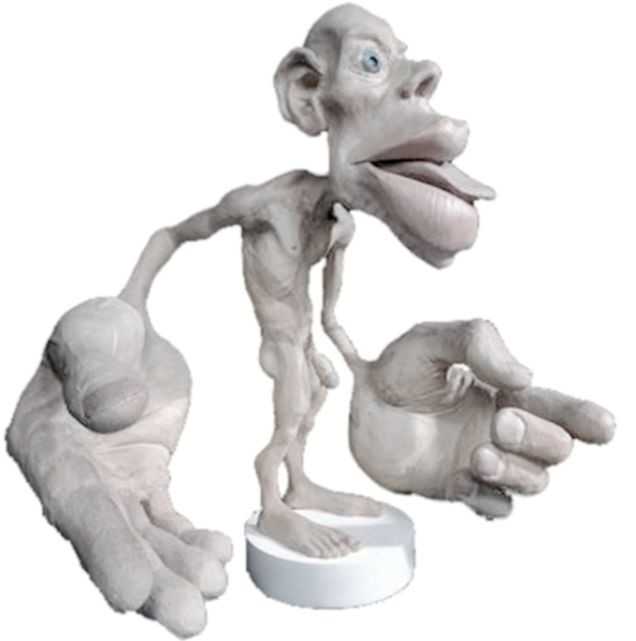

In the 16th century, a theory called Preformationism claimed that sperm contained a preformed, exceedingly minute body referred to as a homunculus, which eventually became a person. This idea of a tiny man had staying power, as today the homunculus is a “body map” based on how much of the cerebral cortex is devoted to sensing each part of the body. Although the idea of a 16th alchemist placing little bodies into a flask conjures a variety of tantalizing images, our program focuses on the mundane, contemporary version of the homunculus. So…what does this have to do with a course that addresses pelvic floor dysfunction? Everything.

Emerging evidence indicates that therapies that include work to enhance body awareness/kinesthetic sense are potent and effective. Our professional training unfortunately, tends to over-emphasize a structural approach. The good news is that manual therapy, to some degree, enhances a client’s body awareness; but when we have more “tools” to capitalize on this synergy between manual therapy and improved body awareness, we have a potent “elixir” to promote change. To quote Deane Juhan, “touching hands are not like pharmaceuticals or scalpels…they are like flashlights in a darkened room.” By using the “flashlight”, we not only contribute to structural change, but neurological change – meaning the more we pay attention to a particular part of our body, the more “real estate” the brain devotes to that part of the body. Increasing the pelvic floor’s “footprint” on the brain can enhance function of the pelvic floor dramatically and quickly. Therefore, rehabilitation to address pelvic floor dysfunction benefits from weaving orthopedic, neurologic and mindfulness practices together.

Emerging evidence indicates that therapies that include work to enhance body awareness/kinesthetic sense are potent and effective. Our professional training unfortunately, tends to over-emphasize a structural approach. The good news is that manual therapy, to some degree, enhances a client’s body awareness; but when we have more “tools” to capitalize on this synergy between manual therapy and improved body awareness, we have a potent “elixir” to promote change. To quote Deane Juhan, “touching hands are not like pharmaceuticals or scalpels…they are like flashlights in a darkened room.” By using the “flashlight”, we not only contribute to structural change, but neurological change – meaning the more we pay attention to a particular part of our body, the more “real estate” the brain devotes to that part of the body. Increasing the pelvic floor’s “footprint” on the brain can enhance function of the pelvic floor dramatically and quickly. Therefore, rehabilitation to address pelvic floor dysfunction benefits from weaving orthopedic, neurologic and mindfulness practices together.

This program is designed to add a new dimension for the skilled pelvic floor practitioner and to also serve practitioners new to this area of practice. There is no internal manual work; rather we draw from our deep knowledge of Yoga, Tai Chi, along with other Chinese internal martial arts (that put lots of emphasis on the pelvic floor for performance) and Feldenkrais to address pelvic floor dysfunction. Some lessons focus directly on the pelvic region and others on integrating the pelvic floor with full body movement. Ultimately, our goal is to help you connect the dots between structural, functional movement and mindfulness practices, as this powerful triad offers practitioners a comprehensive, approach for treating pelvic floor dysfunction.

We hope you’ll come join in New York City on September 18th & 19th. If you do, wear comfortable clothes as the workshop is designed to provide participants opportunities to embody the work…emphasis is placed on labs more than lecture.

Don’t hesitate to contact us if you have any questions.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

You wouldn't place a newborn in a crib without knowing the legs were firmly attached at the right angle to the base. You wouldn't jump on a hammock if the poles or trees were not firmly intact and upright to support the sling. Why would you treat a pregnant woman without checking if her hips were working optimally in proper alignment to support the pelvis, inside which a new life is developing? Let's hope higher level clinicians spend the extra effort to learn about the surrounding areas that affect our specialty, whether it is pelvic floor or spine or sports medicine.

In 2015, Branco et al., published a study entitled, “Three-Dimensional Kinetic Adaptations of Gait throughout Pregnancy and Postpartum.” Eleven pregnant women voluntarily participated in this descriptive longitudinal study. Ground reaction forces (GRF), joint moments of force in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes, and joint power in those same 3 planes were measured and assessed during gait over the course of the first, second, and third trimesters as well as 6 months post-partum. The authors found pregnancy does influence the kinetic variables of all the lower extremity joints; however, the hip joint experiences the most notable changes. As pregnancy progressed, a decrease in the mechanical load was found, with a decrease in the GRF and sagittal plane joint moments and joint powers. The vertical GRF showed the peaks of braking propulsion decreases from late pregnancy to the postpartum period. A significant reduction of hip extensor activity during loading response was detected in the sagittal plane. Ultimately, throughout pregnancy, physical activity needs to be performed in order to develop or maintain stability of the body via the lower quarter, particularly the hips.

In 2015, Branco et al., published a study entitled, “Three-Dimensional Kinetic Adaptations of Gait throughout Pregnancy and Postpartum.” Eleven pregnant women voluntarily participated in this descriptive longitudinal study. Ground reaction forces (GRF), joint moments of force in the sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes, and joint power in those same 3 planes were measured and assessed during gait over the course of the first, second, and third trimesters as well as 6 months post-partum. The authors found pregnancy does influence the kinetic variables of all the lower extremity joints; however, the hip joint experiences the most notable changes. As pregnancy progressed, a decrease in the mechanical load was found, with a decrease in the GRF and sagittal plane joint moments and joint powers. The vertical GRF showed the peaks of braking propulsion decreases from late pregnancy to the postpartum period. A significant reduction of hip extensor activity during loading response was detected in the sagittal plane. Ultimately, throughout pregnancy, physical activity needs to be performed in order to develop or maintain stability of the body via the lower quarter, particularly the hips.

The same authors, in 2013, studied gait analysis in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Branco et al., performed a 3-dimensional gait analysis of 22 pregnant women and 12 non-pregnant women to discern kinetic differences in the groups. Nineteen dependent variables were measured, and no change was noted between 2nd and 3rd trimesters or the control group for walking speed, stride width, right-/left-step time, cycle time and time of support, or flight phases. Comparing the 2nd versus 3rd trimester, a decrease in stride and right-/left-step lengths decreased. The 2nd and 3rd trimesters both showed a significant decrease in right hip extension and adduction during the stance phase when compared to the control group. In this study, the authors also noted increased left knee flexion and decreased right ankle plantar flexion during gait from the 2nd to the 3rd trimester. The bottom line in this study, just as the more recent one suggests, pregnant women need a higher degree of lower quarter stability to ambulate efficiently throughout pregnancy.

Physical therapists are movement specialists with a unique opportunity to analyze how humans function, whether athletes or pregnant women (or even a pregnant athlete). How the hips move and whether or not proper muscles are firing can affect anyone’s gait. The extra demands on the pregnant body require more specific analysis of kinetics by therapists, thus directing the protocols for rehabilitation of this population. It should behoove every pelvic floor specialist, in particular, to attend a course like “Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip and Pelvis" or "Care of the Pregnant Patient" in order to provide patients with the optimal support for the natural “crib” women provide during pregnancy.

Branco, M., Santos-Rocha, R., Vieira, F., Aguiar, L., & Veloso, A. P. (2015). Three-Dimensional Kinetic Adaptations of Gait throughout Pregnancy and Postpartum. Scientifica, 2015, 580374. http://doi.org/10.1155/2015/580374

Branco, M., Santos-Rocha, R., Aguiar, L., Vieira, F., & Veloso, A. (2013). Kinematic Analysis of Gait in the Second and Third Trimesters of Pregnancy.Journal of Pregnancy, 2013, 718095. http://doi.org/10.1155/2013/718095

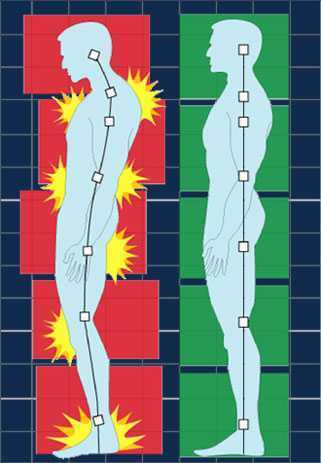

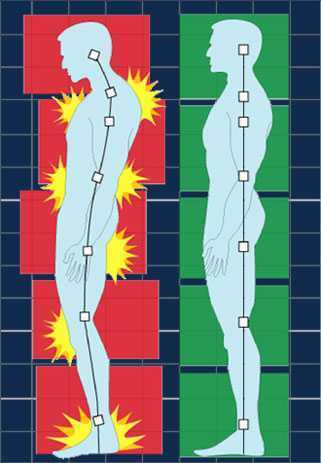

Posture is a concept that rehab clinicians have long hung our hats on, and yet updated models of evaluation and care take into account the truth that there are plenty of humans functioning in poor postures who do not complain of musculoskeletal pain or other dysfunctions. Is postural dysfunction always, or never, causative? As with many things in life, the answer is likely somewhere in between. If our patient arrives at the clinic with a dysfunctional posture and improving their alignment eases discomfort and improves function, we have provided help with addressing posture. It is also likely that we have spent a bit too much time lecturing on the elusive “ideal” posture, when in fact dynamic and adaptive postures are more often occurring throughout a person’s day. Certainly computer postures add to a patient’s movement challenge, and we continue to learn more about the best ways for patients to manage the otherwise potentially static and unhealthy positions that add to many of our patients’ issues.

In regards to the pelvic floor, does changing standing lumbopelvic posture affect pelvic floor muscle (PFM) activation? This is the question asked by researchers from Queen’s University in Canada. (Capson et al., 2011) Sixteen women ages 22-41 who had never given birth and who were continent participated in the study. They were assessed completing five tasks in three different postures: normal lumbopelvic posture, hyperlordosis, and hypolordosis. The tasks included quiet standing, maximal effort cough, Valsalva maneuver, pelvic floor maximal voluntary contraction, and a load-catching activity. A vaginal sensor was to use to collect electromyographic activity of the pelvic floor, and sensors were placed on trunk muscles including the rectus abdominus, external and internal obliques, and erector spinae. A perineometer was utilized separately to record manometry measures, and 3D motion analysis was used to position women in the appropriate lumbopelvic angles. Key results of the investigation are summarized below:

In regards to the pelvic floor, does changing standing lumbopelvic posture affect pelvic floor muscle (PFM) activation? This is the question asked by researchers from Queen’s University in Canada. (Capson et al., 2011) Sixteen women ages 22-41 who had never given birth and who were continent participated in the study. They were assessed completing five tasks in three different postures: normal lumbopelvic posture, hyperlordosis, and hypolordosis. The tasks included quiet standing, maximal effort cough, Valsalva maneuver, pelvic floor maximal voluntary contraction, and a load-catching activity. A vaginal sensor was to use to collect electromyographic activity of the pelvic floor, and sensors were placed on trunk muscles including the rectus abdominus, external and internal obliques, and erector spinae. A perineometer was utilized separately to record manometry measures, and 3D motion analysis was used to position women in the appropriate lumbopelvic angles. Key results of the investigation are summarized below:

- Baseline EMG activity of the PFMs and the trunk muscles was significantly lower in supine versus standing

- PFM EMG activity in standing hypolordotic was higher than normal or typical posture

- Trunk muscle EMG activity did not significantly change during the 3 quiet standing postures

- For maximal PFM contraction and for cough, Valsalva, and load-catching, lower EMG activity was measured in standing in hyperlordotic or hypolordotic postures compared to “normal” or habitual posture

- With cough, all muscles except the erector muscles demonstrated increased activity

- In general, EMG activity was increased in trunk muscles when the subjects were in their habitual posture

- Related to timing of the rectus abdominus (RA) muscles, the RA were activated 106 ms before the PFM

- In standing, the intravaginal pressure was significantly higher in the hypolordotic posture compared to hyperlordotic posture

How can we put this valuable research to work in the clinic? This study validates a typical EMG activity finding of increased activity during standing versus lying, which makes sense given the pelvic tasks of working against gravity. In addition, it may be the case that our patients can generate an optimal amount of pelvic muscle contraction (when strengthening) in a more neutral posture. It may also be worth considering that for our patients who are chronically holding, perhaps a tendency for them to be in a hypolordotic posture is perpetuating their dysfunction. The data on timing of trunk and pelvic floor muscles was less consistent, although not less interesting. This research can also be implemented as an evaluation and intervention in the clinic- let’s be sure that we are using methods of feedback such as EMG, real-time ultrasound, or pressure biofeedback in various and functional positions. Then we can find out what seems to work best for our patient, whether the goal is to increase or decrease muscle activity and function.

Capson, A. C., Nashed, J., & Mclean, L. (2011). The role of lumbopelvic posture in pelvic floor muscle activation in continent women. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology21(1), 166-177.

Assuring patients with chronic pain they are not crazy by explaining the neurophysiology behind what is happening in their brain and body can be life changing. Increasing our patients’ knowledge about physical conditions can reduce anxiety and provide hope. As a healthcare provider, being confident in your differential diagnosis skills can help narrow down the physical source of pain, weed out the psychological components, and connect the dots to the neurological influence on the patient’s persistent symptoms.

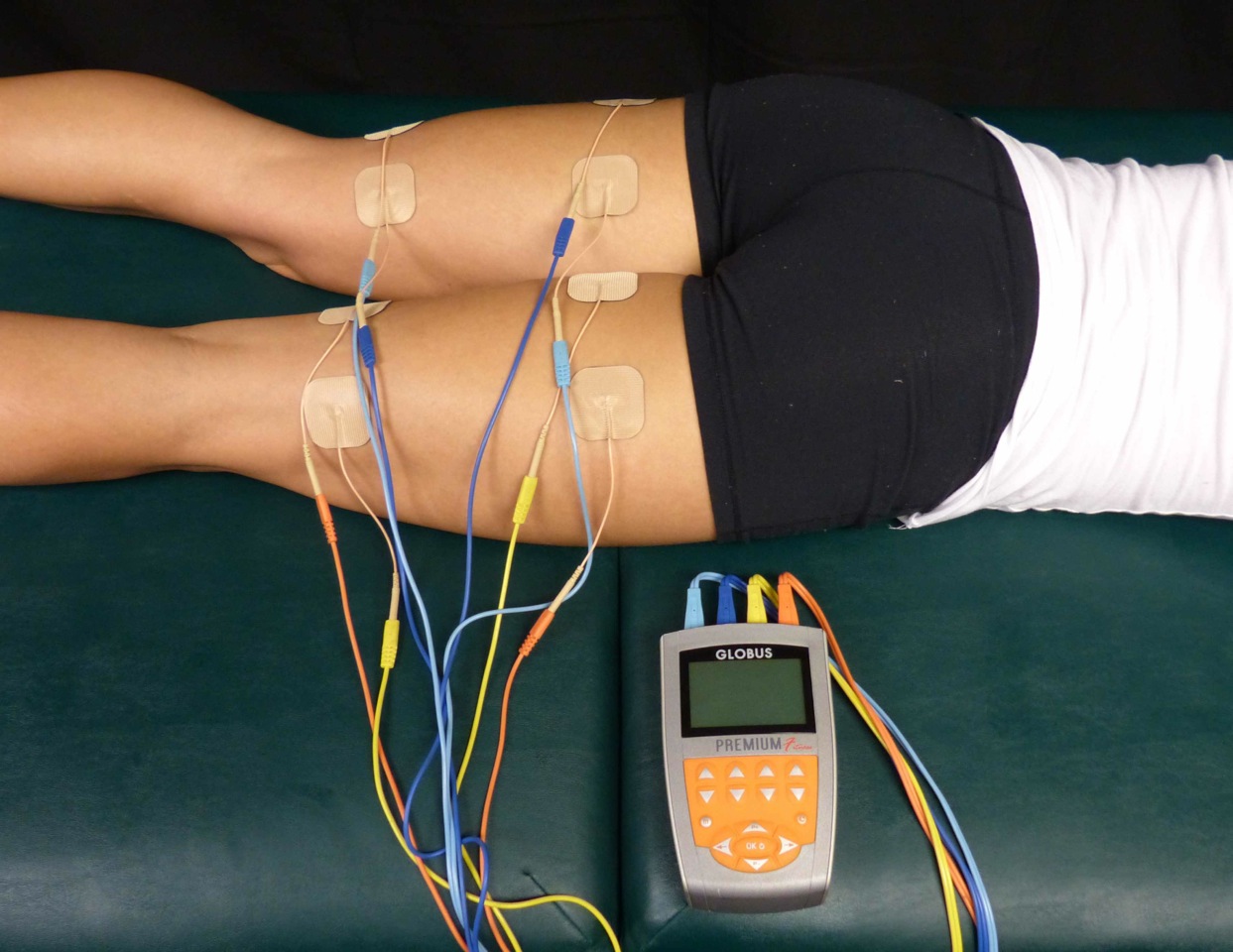

A 2015 article in Pain Medicine (Gurian et al) found a direct association between pain sensitivity and treatment of chronic pelvic pain. The study involved 58 women with at least 6 months of pelvic pain, and they were evaluated on pain threshold using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation before treatment and 6 months after a multidisciplinary approach to treatment of the pelvic pain. Pain intensity was also evaluated using the visual analog scale and the McGill questionnaire. Depending on the specific condition, treatment included manual therapy, physical therapy, pain medications, laparoscopy, oral contraceptives, nutrition intervention, or psychological support. After receiving treatment for 6 months, the pain threshold mean improved from 14.2 to 17.4. The effect sizes of 0.86 in the group with pain reduction and 0.53 in the group not achieving pain reduction were both within the 95% confidence interval. The authors concluded in this study that central sensitization does occur in patients with chronic pelvic pain, and treatment can reduce the general pain sensitivity of the patient.

A 2015 article in Pain Medicine (Gurian et al) found a direct association between pain sensitivity and treatment of chronic pelvic pain. The study involved 58 women with at least 6 months of pelvic pain, and they were evaluated on pain threshold using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation before treatment and 6 months after a multidisciplinary approach to treatment of the pelvic pain. Pain intensity was also evaluated using the visual analog scale and the McGill questionnaire. Depending on the specific condition, treatment included manual therapy, physical therapy, pain medications, laparoscopy, oral contraceptives, nutrition intervention, or psychological support. After receiving treatment for 6 months, the pain threshold mean improved from 14.2 to 17.4. The effect sizes of 0.86 in the group with pain reduction and 0.53 in the group not achieving pain reduction were both within the 95% confidence interval. The authors concluded in this study that central sensitization does occur in patients with chronic pelvic pain, and treatment can reduce the general pain sensitivity of the patient.

Kutch et al., (2015) performed a study regarding the change in men’s resting state of neuromotor connectivity as affected by chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS), showing men are also subject to central sensitization. Fifty-five men (28 males with pelvic pain for at least 3 months and 27 healthy males) completed the study, with resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging detecting the functional connectivity of the pelvis with the motor cortex (pelvic-motor). The right posterior insula and pelvic-motor functional connectivity was found to be significantly different in men with chronic pelvic pain and prostatitis versus the healthy control group. Contraction of the pelvic floor corresponded with activation of the medial aspect of the motor cortex, while the left motor cortex was more associated with contraction of the right hand. The authors concluded this relationship may explain the viscerosensory and motor processing changes that occur in men with CP/CPPS and could be the most important marker of brain function alteration in this group of patients.

As more research is being done on the neurophysiological level of pain, more truth can support the “it’s all in your head” accusation. However, it is a positive light to shed for a patient. The brain is powerful and controls how pain is perceived globally. Proper treatment of a chronic pelvic floor condition, for women and men, can help reduce stress on the brain and lessen pain sensitivity and perception in our patients. Never let a patient pursue the self-perception that they are crazy. Explain central sensitization and how sometimes the brain wins in the war of “mind over matter”; however, give them hope, explaining how the proper treatment can lessen the intensity of the battle wounds.

Maria Beatriz Ferreira Gurian, Omero Benedicto Poli Neto, Julio Cesar Rosa e Silva, Antonio Alberto Nogueira, Francisco Jose Candido dos Reis. (2015). Reduction of Pain Sensitivity is Associated with the Response to Treatment in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Pain Medicine. 16 (5) 849-854; DOI: 10.1111/pme.12625

Kutch, J. J., Yani, M. S., Asavasopon, S., Kirages, D. J., Rana, M., Cosand, L., … Mayer, E. A. (2015). Altered resting state neuromotor connectivity in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: A MAPP: Research Network Neuroimaging Study. NeuroImage : Clinical, 8, 493–502. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2015.05.013

III. Postpartum

Nourishing my baby and myself, a complicated dichotomy

The care I received from the doctors, nurses, and hospital staff during labor, delivery, and postpartum period was excellent. I felt all the staff members explained all procedures for myself and the baby. The labor and delivery nurses were helpful and compassionate. They showed me how to breastfeed the baby, assisted me with skin to skin contact, and taught my husband and I how to care for the baby when we took her home. The birth center site at the hospital was amazing. I had an individual birthing suite with a bathroom, a television, a bathtub and a place for my husband to sleep. Health care for the baby and I following delivery continued to be excellent. I had a surgical follow up one week later with my doctor and another postpartum visit at 6 weeks. At each visit I was given The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (a scale to help identify postpartum depression) as well as educational pamphlets on self-care following a cesarean delivery. The only complaints I had that required assistance from a health care provider was with getting baby to latch with breast feeding and neck and shoulder pain from breast feeding the baby. I took it upon myself to work on core and hip exercises I would give a postpartum patient who had undergone a cesarean delivery and was working on my scar tissue to prevent problems with bladder, bowel, abdomen, and uterus. I sought some massage for my neck and shoulders and did my physical therapy exercises for my neck and shoulders. I sought a lactation consultant for the latching issues with breast feeding. Seeking care helped resolve these issues which reduced my neck and shoulder pain and helping me enjoy breastfeeding my baby.

The care I received from the doctors, nurses, and hospital staff during labor, delivery, and postpartum period was excellent. I felt all the staff members explained all procedures for myself and the baby. The labor and delivery nurses were helpful and compassionate. They showed me how to breastfeed the baby, assisted me with skin to skin contact, and taught my husband and I how to care for the baby when we took her home. The birth center site at the hospital was amazing. I had an individual birthing suite with a bathroom, a television, a bathtub and a place for my husband to sleep. Health care for the baby and I following delivery continued to be excellent. I had a surgical follow up one week later with my doctor and another postpartum visit at 6 weeks. At each visit I was given The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (a scale to help identify postpartum depression) as well as educational pamphlets on self-care following a cesarean delivery. The only complaints I had that required assistance from a health care provider was with getting baby to latch with breast feeding and neck and shoulder pain from breast feeding the baby. I took it upon myself to work on core and hip exercises I would give a postpartum patient who had undergone a cesarean delivery and was working on my scar tissue to prevent problems with bladder, bowel, abdomen, and uterus. I sought some massage for my neck and shoulders and did my physical therapy exercises for my neck and shoulders. I sought a lactation consultant for the latching issues with breast feeding. Seeking care helped resolve these issues which reduced my neck and shoulder pain and helping me enjoy breastfeeding my baby.

Before having my daughter, I had preconceived notions about postpartum care. For the last ten years since I started working with women’s health patients I have heard repeatedly from my patients that they felt they did not receive comprehensive postpartum care. Many of these women hopped from health care provider to health care provider, sometimes taking years to resolve orthopedic or pelvic floor problems from their pregnancy or labor and delivery experience. Quality postpartum care was my soap box issue and still is. That being said, I was very satisfied with my postpartum health care experience. My experience revealed that support and education about postpartum problems as well as proactive healthcare for theses challenges is becoming mainstream. I have always felt that women in our country need better post-partum care and I am happy to see improvements being made. We may forget between the constant baby changing, soothing, and feedings that mom needs some care too. I am not sure that we always remember that there have been 9 months of physiologic changes occurring to a woman’s body. Additionally, physical trauma that occurs with caesarean or vaginal delivery. A mother may need physical therapy for exercises to strength abdominals or back, help for bowel or bladder problems, manual therapy for painful intercourse, or scar tissue work for abdominals or pelvic floor.

I think as a society we are getting more aware of the influence of hormones, crying babies, sleep deprivation, and a heavy work load can overwhelm a postpartum mother. Based on my experience only, I think we are doing a better job of monitoring postpartum depression, pain management, and pelvic floor problems. I was so pleased at the availability of information and counseling opportunities presented to me during my birthing and postpartum experience. I received so much encouragement and permission to seek help from others during my postpartum healing.

Now that patients are being routinely counseled on postpartum self-care for mind and body we need to help them achieve successful outcomes. As health care providers, we should help postpartum patients decide how to include self-care with their new routine with baby. Caring for a baby takes a lot of time! My postpartum experience was likely similar to other women, where I had very little time to do all the “things I should be doing.” (For me this included neck, shoulder, abdominal, back, and pelvic exercises. As well as attending pediatrician, massage therapy, and lactation appointments.) The baby needs to feed constantly. By the time you feed, change, and soothe the baby (and pump if needed) it is almost time to do it again. You may never have more than an hour to get things done or get some sleep. As a mother there are many novel challenges to face, skills to learn, and emotional stress from fatigue and hormones. On top of all that, oh yeah, you should exercise, eat healthy, and if you are lucky shower and sleep! The point is, being a mother is challenging and we are all doing the best job we can. It is difficult to care for your baby while taking care of yourself. Reflecting back on my “birth story” has helped me empathize with my patients but also helped me to see that as health care providers, we should continue to provide education to our patients on self-care and continue to encourage them to seek care for their problems. However, to really help our patients successfully heal, we need to help them figure out how postpartum self-care blends into their new life with baby.