The following post comes to us from Herman & Wallace faculty member Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, BCB-PMD, PRPC. Allison authored "Use of transabdominal ultrasound imaging in retraining the pelvic-floor muscles of a woman postpartum" and is a leading expert in the use of ultrasound imaging for pelvic rehab. She is the author and instructor of the Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging: Women’s Health and Orthopedic Topics offered with Herman & Wallace.

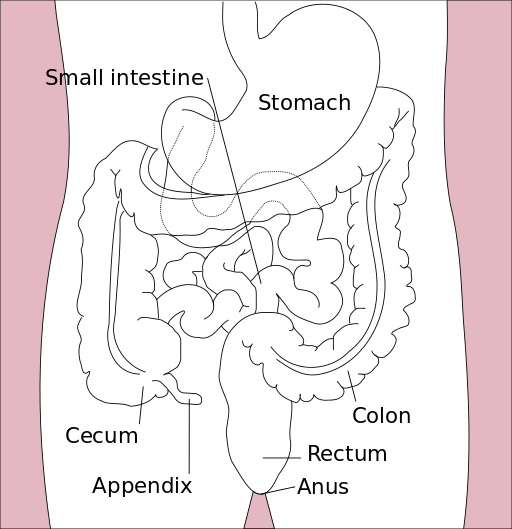

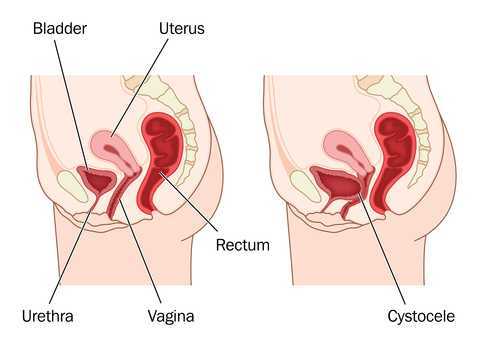

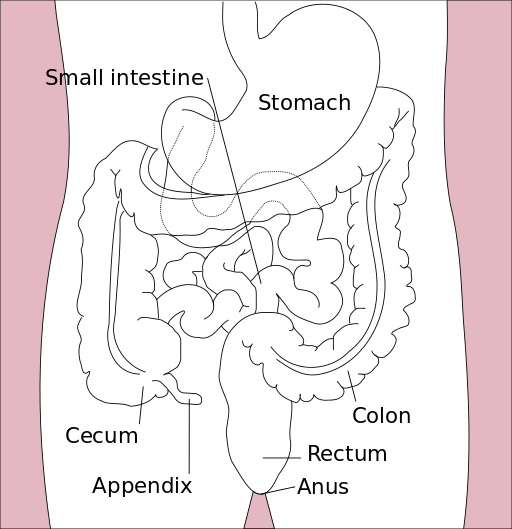

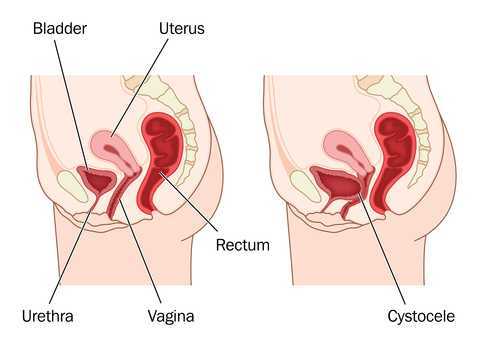

In the pelvic floor series we learn how to perform examinations for cystoceles and rectoceles. It can be more difficult for therapists to examine and quantify the degree of uterine descent. In the last few years translabial ultrasound imaging has also been used to identify what is happening in the anterior compartment upon Valsalva and pelvic floor contraction, including the uterus. This is helpful when trying to determine the degree of uterine prolapse. Degree of pelvic organ descent visible on by ultrasound has been shown to have a near-linear relationship with measures on the POPQ.

Clinically we see that some patients with severe prolapses have few symptoms, while other patients with smaller prolapses will have more severe complaints of symptoms. This can be puzzling to the clinician who is trying to treat prolapse patients. Shek and Dietz performed a study to set cutoff measures of uterine descent that will predict symptoms of prolapse. Translabial ultrasound imaging was performed on 538 women with 263 women reporting prolapse symptoms. Seventy-five percent of the women presented with grade two or greater prolapse on the POPQ, with most of being cystoceles or rectoceles. The women with more complaints of symptoms of prolapse were more likely to have uterine prolapse. There was a strong association between degree of uterine descent and symptoms of prolapse. They determined that an optimal cutoff to predict symptoms of prolapse due to uterine descent is a cervix descending to 15 mm above the pubic symphysis.

Clinically we see that some patients with severe prolapses have few symptoms, while other patients with smaller prolapses will have more severe complaints of symptoms. This can be puzzling to the clinician who is trying to treat prolapse patients. Shek and Dietz performed a study to set cutoff measures of uterine descent that will predict symptoms of prolapse. Translabial ultrasound imaging was performed on 538 women with 263 women reporting prolapse symptoms. Seventy-five percent of the women presented with grade two or greater prolapse on the POPQ, with most of being cystoceles or rectoceles. The women with more complaints of symptoms of prolapse were more likely to have uterine prolapse. There was a strong association between degree of uterine descent and symptoms of prolapse. They determined that an optimal cutoff to predict symptoms of prolapse due to uterine descent is a cervix descending to 15 mm above the pubic symphysis.

This study intrigues me and makes me wonder how much we are focusing on cystoceles and rectoceles and not looking at uterine prolapses. Using translabial ultrasound imaging is a nice tool to allow the clinician to see what is going on with all of the pelvic organs. With one Valsalva maneuver you are able to assess a lot of information including support of the pelvic organs. It also gives the clinician another way to quantify the degree of prolapse. Ultrasound imaging is a wonderful tool that clinicians can use for assessment as well as a biofeedback tool. If you are interested in learning how to perform this type of assessment, I will be teaching Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging: Women’s Health and Orthopedic Topics May 1-3 in Dayton, OH.

Shek KL, Dietz HP. What is abnormal uterine descent on translabial ultrasound? Int. Urogynecol J. 2015; 26(12)1783-7.

Today we are honored to present our featured Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Jessica Dorrington, PT, MPT, OCS, PRPC, CMPT, CSCS! Jessica was kind enough to answer a few questions about her role in pelvic rehab.

Describe your clinical practice:

Our clinic practice is an outpatient orthopedic private practice. We are committed to making individual results accessible through compassionate therapeutic care. Our practice spans treating men, women and children through a realm of urologic, gynecologic, obstetric, and colorectal conditions- as well as orthopedic conditions.

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

Initially, I was an outpatient orthopedic physical therapist. Within the first few months of my career, the clinic I was working at needed someone to just “teach Kegel exercises”. When I realized the impact that you could have on someone’s life, I was immediately drawn to the pelvic rehabilitation field. I saw getting someone even 75 percent improvement was a whole different success than getting a shoulder patient 75 percent better that could now throw their ball to their dog. It was restoring relationships, saving marriages, and giving women the freedom to go do things they could not do before.

What/who inspired you to become involved in pelvic rehabilitation?

My patients inspire me every day. I initially started treating incontinence patients and then gradually added chronic pain patients to my case load. Each patient that achieved such success with pelvic rehabilitation inspired me to wanting to learn more and reach out to more patient’s in need of physical therapy. This led me into treating men and children with pelvic rehabilitation issues. My favorite story that initially started me on my career path was a 95 year old women who came to me for low back pain. I asked her if she had any incontinence. After 4 visits, she removed a pessary (that she had for the past 55 years-since the birth of her last child) and was painfree and fully continent!

What patient population do you find most rewarding in treating and why?

My favorite patients are those that have seen every specialist and have complex histories. Being able to really listen to their story and give them answers in a health care setting that has not found a solution to their condition is such a wonderful experience. Our professional affords us such a great opportunity to really get to know these patients, dive deep into their history and put the puzzle pieces together for them in a way most professions do not have time for in our current medical model.

If you could get a message out to physical therapists about pelvic rehabilitation what would it be?

As I have grown as a practitioner over the years, the biggest message I have is to really listen to each story. Even a simple SI joint dysfunction patient or a seemingly straight forward stress incontinence patient can have subjective and objective information that really points to the root of the issue. We can really serve these patients the best and premier care if we are up to date on our dermatologic, hormonal influences, musculoskeletal system, and are strong orthopedic clinicians.

What has been your favorite Herman & Wallace Course and why?

Michelle Lyons Athlete and the Pelvic Floor course was wonderful. Michelle is a gifted facilitator of education, has so many pearls of valuable resources and tidbits. She also does a wonderful job combining the orthopedic and pelvic floor world together.

What lesson have you learned from a Herman & Wallace instructor that has stayed with you?

Holly has been truly inspirational to me as she is so passionate about her career and passionate about our profession. Her education on hormones really helps me to sort out for patients when I feel there is a hormonal influence.

What do you find is the most useful resource for your practice?

A pelvic model and Adrian Louw’s Explanation of Pain/Neuroscience education has been such a great resource. For most pelvic pain patient’s there is some sort of sensitive nervous system overlie and the way he educates patients has been lifechanging. The other strong resource has been motivational interviewing education. This allows to really guide these patients in a way that assesses their readiness and motivation for change. The other resource is using the rehabilitative ultrasound imaging. Jackie Whittaker has been such a wonderful mentor to me and this resource has revolutionized the way that I treat diastasis patients, local stabilization, and men and pediatric populations.

What motivated you to earn PRPC?

I am doing more speaking engagements to other medical providers and am doing a lot of mentorship. Being in these roles, I feel having credentials to back the clinical experience is really valuable.

What makes you the most proud to have earned PRPC?

I took the exam without studying, largely because I wanted to see if my skills and knowledge was antiquated (being I have been doing pelvic floor therapy x 14 years). I found the test to be really fun and challenging in an exciting way. The case studies were true examples of the complex patients we treat and so I enjoyed the process.

What advice would you give to physical therapists interested in earning PRPC?

My advice would be to really do some great critical reasoning around your current patients. We learn best by our patients and doing a practice of critically thinking and differential diagnosis around your current patients will give a platform for this. I recalled treating several patients during the examination and could picture very similar patient presentations. The other piece I would recommend is reviewing your anatomy and pharmacology.

What is in store for you in the future?

I am continually blessed to be able to lead a wonderful team of therapists at our outpatient private practice. We are launching a labor and delivery program and post-partum evaluations. Educating the medical community at large has been a focus of mine and I would like to continue to do so to get the word out about pelvic floor PT. I have been asked to speak at the United Nations next Spring and will be presenting about Pelvic Floor in relation to Motherhood Maternity. Mentorship to pelvic floor therapists and students also continues to be a focus.

What role do you see pelvic health playing in general well-being?

I strongly feel pelvic health therapists could play a role in every orthopedic patient’s care. We have so many tools to really evaluate patients from a full body spectrum and have the ability to address any lumbopelvic condition with true depth. Having this vital information about their bodies can really empower all individuals to return to what they love to do in an active healthy lifestyle!

“Please stress the need to examine men…For some reason, most female PT`s shy away from a male’s private parts totally. It would be great if females were taught that it's important to go there…And treat us as equals in this arena.”

This is an excerpt from a recent email we received at Herman & Wallace headquarters, and it highlights a common theme, that of patient access to care. While there are many factors driving patient access to pelvic health, availability of therapists trained in various conditions is certainly one major issue. By the time any patient is referred to pelvic rehabilitation, they have already overcome the challenge of many providers not being aware that there is help for pelvic health issues, and insurance or payment hurdles that can also cause a patient to delay or avoid recommended treatment. Many physical therapy programs have done an outstanding job in developing and marketing women’s health programs, with men’s health programs addressing post-prostatectomy care or male pelvic pain coming along almost as an afterthought.

This is an excerpt from a recent email we received at Herman & Wallace headquarters, and it highlights a common theme, that of patient access to care. While there are many factors driving patient access to pelvic health, availability of therapists trained in various conditions is certainly one major issue. By the time any patient is referred to pelvic rehabilitation, they have already overcome the challenge of many providers not being aware that there is help for pelvic health issues, and insurance or payment hurdles that can also cause a patient to delay or avoid recommended treatment. Many physical therapy programs have done an outstanding job in developing and marketing women’s health programs, with men’s health programs addressing post-prostatectomy care or male pelvic pain coming along almost as an afterthought.

So what is really limiting the care of men who wish to overcome urinary, pain, or sexual dysfunction? For many locations around the country, there simply is not enough awareness of the scope of pelvic rehab, the nearest pelvic rehab provider may be far away geographically (or have a months-long waiting list), or the clinic may limit pelvic healthcare to women. If the clinic chooses to only provide care to women, what are we being discriminating about? The word “discriminate” has at least two rather distinct definitions, one that is more negative, and meaning that we are acting in an unjust or prejudicial manner, and another that simply means we are recognizing a difference between patient groups. If we choose to discriminate against treating men in a pelvic health setting, it’s easy to understand that if a therapist has never been instructed in how to examine a male patient, it may be prudent to avoid such evaluation until training is completed. We can find examples of this situation in other aspects of clinical care: if I have never taken proper training in evaluation of the vestibular system, for example (a condition that historically has not always been comprehensively instructed in school), then it’s in my best interest (and that of the patient) to only provide such care once I have taken appropriate training.

If our care of male pelvic health conditions is due to lack of specific training, what is our professional responsibility for acquiring training in conditions such as post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence, male genital pain, or erectile dysfunction? If we are to serve the pelvic health populations well, our training should progress to include lifespan issues for all ages and all genders. If we actively choose to avoid treating a population or condition, is that fair to the community seeking care? The ethics of choosing not to treat patients of a particular gender or condition are interesting to consider, but are not the scope of this post. On the other hand, the business side of being able to market to and welcome male patients in our clinics is very positive, and of course, all of our patients tend to be grateful for what we offer.

If you are interested in learning more about male pelvic healthcare, the Institute has several courses that can help you do so. These courses include an introduction to men at the Pelvic Floor Level 2A course, the Male Pelvic Floor: Function, Dysfunction and Treatment course (3 days dedicated to evaluation and treatment of urinary, sexual, and pain dysfunction), the Post-Prostatectomy course, as well as several manual therapy courses such as our myofascial courses. It is understandable that pelvic health for men may be less familiar territory for many of us based on our graduate training and experiences. If fear or discomfort is holding us back, at least attending a training course can help provide strategies and tools for gaining more comfort in treating men. We are at an exciting time in the pelvic health field when treating men is gaining more ground. If you are not already, join this exciting movement by signing up for one of the many classes available to you!

Many therapists start their career feeling a bit intimidated to work with women who are pregnant. A common and understandable concern is that something the therapist will do during examination or treatment may harm the patient. While there are certainly things to avoid when working with a patient who is pregnant there are also many therapeutic strategies that can help a woman thrive during her pregnancy and beyond. When women have pre-existing issues such as a disease or physical challenge, or when she develops an illness during pregnancy, the therapist needs to rely upon more knowledge- this knowledge is something she rarely learns in school, but more likely in continuing education environments. A recent article asked the question “are women getting sicker, and are there more high-risk pregnancies now than ever before?”

Researchers studied trends in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States in order to answer this question, and the answer is a definitive “yes”. Several studies describe increases in the rates of maternal morbidity, with issues such as cardiac and pulmonary complications, and the severe blood pressure fluctuations associated with eclampsia. Gestational diabetes, and postpartum rates for hemorrhage, perineal lacerations, and maternal infections have also risen. Part of the reason for more women carrying pregnancies more successfully or longer when they are ill may be contributed to newer treatments for conditions such as diabetes, yet this does not explain entirely the increase in maternal morbidity. Increased cesarean births, longer labors with epidural anesthesia, pre-pregnancy obesity, rates of multifetal pregnancies, and the rising age of mothers are other factors to be considered.

Researchers studied trends in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States in order to answer this question, and the answer is a definitive “yes”. Several studies describe increases in the rates of maternal morbidity, with issues such as cardiac and pulmonary complications, and the severe blood pressure fluctuations associated with eclampsia. Gestational diabetes, and postpartum rates for hemorrhage, perineal lacerations, and maternal infections have also risen. Part of the reason for more women carrying pregnancies more successfully or longer when they are ill may be contributed to newer treatments for conditions such as diabetes, yet this does not explain entirely the increase in maternal morbidity. Increased cesarean births, longer labors with epidural anesthesia, pre-pregnancy obesity, rates of multifetal pregnancies, and the rising age of mothers are other factors to be considered.

The more we know as health care providers about how maternal morbidity affects our rehabilitation efforts, the more we can contribute to a woman’s pregnancy and postpartum health. If you would like to learn more about caring for women during pregnancy and during the postpartum period, Herman & Wallace offers the Pregnancy and Postpartum Series. The following courses are available this year:

Care of the Pregnant Patient - Somerset, NJ

Apr 30, 2016 - May 1, 2016

Care of the Pregnant Patient - Akron, OH

Sep 10, 2016 - Sep 11, 2016

Peripartum Special Topics - Seattle, WA

Nov 12, 2016 - Nov 13, 2016

Tillett, J. (2015). Increasing Morbidity in the Pregnant Population in the United States. The Journal of perinatal & neonatal nursing, 29(3), 191-193.

As pelvic rehabilitation providers, it may be safe to assume a lot of us are treating adults with bladder and bowel dysfunction. Often we get questions from these patients about treatment for children with voiding dysfunction. How comfortable are we treating children for these problems and what would we do? Pediatric voiding dysfunction and bowel problems are common and can have significant consequences to quality of life for the child and the family, as well as negative health consequences to the lower urinary tract if left untreated. No clear gold standard of treatment for pediatric voiding dysfunction has been established and treatments range from behavioral therapy to medication and surgery.

A randomized controlled trial in 2013 that was published in European Journal of Pediatrics, explores treatment options for pediatric voiding dysfunction. Pediatric voiding dysfunction is defined as involuntary and intermittent contraction or failure to relax the urethral striated sphincter during voluntary voiding. The dysfunctional voiding can present with variable symptoms including urinary urgency, urinary frequency, incontinence, urinary tract infections, and abnormal flow of urine from bladder back up the ureters (vesicoureteral reflux).

A randomized controlled trial in 2013 that was published in European Journal of Pediatrics, explores treatment options for pediatric voiding dysfunction. Pediatric voiding dysfunction is defined as involuntary and intermittent contraction or failure to relax the urethral striated sphincter during voluntary voiding. The dysfunctional voiding can present with variable symptoms including urinary urgency, urinary frequency, incontinence, urinary tract infections, and abnormal flow of urine from bladder back up the ureters (vesicoureteral reflux).

The 2013 study compared 60 children over one year who were diagnosed with dysfunctional voiding into two treatment groups. One group received behavioral urotherapy combined with PFM (pelvic floor muscle) exercises while the other group received just behavioral urotherapy. The behavioral urotherapy consisted of hydration, scheduled voiding, toilet training, and high fiber diet. Voiding pattern, EMG (electromyography) activity during voids, urinary urgency, daytime wetting, and PVR (post-void residue) were assessed at the beginning and end of the one year study with parents completing a voiding and bowel habit chart as well as uroflowmetry with pelvic floor muscle sEMG (surface electromyography) was administered to the child for voiding metrics.

All parents and children in both groups received education about urinary and gastrointestinal tract function as well as healthy bladder habits, effects of high fiber diet, scheduled voiding, and normal mechanics of toilet training. For the group that completed PFM exercises and education, they participated in 12 sessions (2x/week for 30 minutes) to learn the PFM exercises under the guidance of a single physical therapist. There was bimonthly follow up for both groups throughout the 12 months to ensure retention and application of the behavioral urotherapy.

The goal of the PFM exercises for the children was too restore the normal function of the PFM’s and their coordination with abdominal muscles. The exercises that the children completed, included exercises with and without a swiss ball. The exercises without a swiss ball included breathing with the diaphragm, Transversus Abdominus muscle isolation, hip adductor squeeze (isolation), bridging with PFM relaxation, and cat/camel to improve lumbopelvic coordination. Swiss ball exercises included seated PFM contraction and relaxation exercise with a seated lift and relax, supine bridge with roll out on the ball with PFM contraction, and supine swiss ball lift with the legs and pelvic contraction. (Pictures and more details about how the exercises were carried out in the article itself.)

The conclusion of the study was that the functional PFM exercises with swiss ball combined with behavioral urotherapy reduced the frequency of urinary incontinence, PVR (post void residue), and the severity of constipation in children with voiding dysfunction. The children in the combined group showed improvements with voiding pattern, reduced EMG activity during voids, reduced urgency, reduced daytime wetting, and improvements with more complete emptying with voids (reduced PVR).

The Functional PFM exercises are easy to teach and easy for children to complete. They are a safe, inexpensive, and effective treatment option for children with dysfunctional voiding. PFM exercises combined with behavioral urotherapy seems to be a logical treatment option for treating pediatric voiding dysfunction.

To learn more about pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction and treatment for it consider attending Dawn Sandalcidi's Pediatric and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction course. The three opportunities in 2016 are Pediatric Incontinence - Augusta, GA April 16-18, Pediatric Incontinence - Torrance, CA June 11-12, and Pediatric Incontinence - Waterford, CT on September 17-18.

Seyedian, S. S. L., Sharifi-Rad, L., Ebadi, M., & Kajbafzadeh, A. M. (2014). Combined functional pelvic floor muscle exercises with Swiss ball and urotherapy for management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Pediatrics, 173(10), 1347-1353.

As a child, I remember my grandmother rubbing my lower back to help me pass my stubborn stool, a problem which landed me in the hospital twice before I turned 10. Decades later, after the birth of my first baby, I had a grade III perineal tear that made me afraid I would never be able to control my stool from passing. At the time of each situation, I had no idea how many people of all ages experience the two extremes of bowel dysfunction. Thankfully, for patients struggling with either issue, whether it is chronic constipation or fecal incontinence, healthcare practitioners are becoming knowledgeable in how to treat both effectively through classes such as the Herman & Wallace course, “Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction & the Pelvic Floor.”

In 2014, Kelly Scott, MD, authored an article entitled, “Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence.” She reviews the current literature and notes this area of study lacks high quality randomized controlled trials, and further research is needed to provide evidence on the efficacy of different treatment protocols. Up to 24% of the adult population has been shown to experience fecal incontinence. Under the umbrella of pelvic floor rehabilitation lies pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback, rectal balloon catheters for volumetric training, external electrical stimulation, and behavioral bowel retraining. The goals of various biofeedback methods include the following: provide endurance training specifically for the anal sphincter and pelvic floor; improve rectal sensitivity and compliance; and, increase coordination and sensory discrimination of the anal sphincter. Overall, the success rate of pelvic floor rehabilitation for fecal incontinence in most of the studies is 50% to 80%, and it is considered safe as well as effective.

In 2014, Kelly Scott, MD, authored an article entitled, “Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence.” She reviews the current literature and notes this area of study lacks high quality randomized controlled trials, and further research is needed to provide evidence on the efficacy of different treatment protocols. Up to 24% of the adult population has been shown to experience fecal incontinence. Under the umbrella of pelvic floor rehabilitation lies pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback, rectal balloon catheters for volumetric training, external electrical stimulation, and behavioral bowel retraining. The goals of various biofeedback methods include the following: provide endurance training specifically for the anal sphincter and pelvic floor; improve rectal sensitivity and compliance; and, increase coordination and sensory discrimination of the anal sphincter. Overall, the success rate of pelvic floor rehabilitation for fecal incontinence in most of the studies is 50% to 80%, and it is considered safe as well as effective.

On the other end of the spectrum, Vazquez Roque and Bouras (2015) published an article regarding management of chronic constipation. Chronic constipation (CC) in the general population has a prevalence of 20%, and the elderly population has a higher rate than the younger population. Chronic constipation is commonly treated with stool softeners, fiber supplements, laxatives, and secretagogues. However, as in all areas of healthcare, a thorough examination needs to be performed to assess the source of the problem. Determining whether a patient exhibits slow transit constipation or a true pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) via blood work, rectal exam, and appropriate PFD tests is essential to provide the appropriate treatment. When the CC culprit is dysfunction of the pelvic floor, clinical trials have proven the efficacy of pelvic floor rehabilitation and biofeedback, making them optimal treatments.

When research indicates a particular type of rehabilitation is effective for treating a wide scope of issues in an area of the body, learning how and when to implement the techniques is paramount for a well-rounded practitioner. Most of us do not dream of treating chronic constipation or fecal incontinence; but, as we mature in our clinical practice, the spectrum of dysfunctions we discover through diagnostic testing and experience grows. Continuing education in previously unexplored territories can only expand the population to whom we provide relief.

Scott, K. M. (2014). Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 27(3), 99–105.

Vazquez Roque, M., & Bouras, E. P. (2015). Epidemiology and management of chronic constipation in elderly patients. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 919–930.

The following comes to us from Felicia Mohr, DPT, a guest contributor to the Pelvic Rehab Report.

Vaginal mesh kits were used frequently early in the millennium as they led to high initial anatomic success rates with peak use between 2008 and 2010. Objectively they seemed to help elevate women’s pelvic organs to appropriate anatomical locations. Unfortunately there has been a high rate (10% according to a review of current literature on PubMedBarski 2015) of mesh erosion causing recurrent prolapse and/or stress urinary incontinence. Also there are cases when the mesh product perforates surrounding organs causing numerous dangerous complications. The rate of mesh-related complications according to current research is 15-25%. As a result, the FDA has reclassified the risk of synthetic mesh into a higher risk category so that the public has an increased awareness of the risk involved in these types of surgeries.

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2015, reviewed the risk factors for mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (Deng, et al). They concluded the following factors increase risk of mesh erosion: younger age, more childbirths, premenopausal states, diabetes, smoking, concomitant hysterectomy, and surgery performed by a junior surgeon. Moreover, concomitant POP surgery and preservation of the uterus may be the potential protective factors for mesh erosion.

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2015, reviewed the risk factors for mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (Deng, et al). They concluded the following factors increase risk of mesh erosion: younger age, more childbirths, premenopausal states, diabetes, smoking, concomitant hysterectomy, and surgery performed by a junior surgeon. Moreover, concomitant POP surgery and preservation of the uterus may be the potential protective factors for mesh erosion.

It is a common practice to perform a hysterectomy with a POP surgery. Reason being that the oversized uterus from childbearing adds extra weight on pelvic organs. However, the latter study as well as two other recent studies published in 2015 (Huang, Farthmann) also provide evidence that there is no benefit to a concomitant hysterectomy at the 2.5 year follow up and can lead to less satisfaction with surgery according to patient surveys respectively.

Keep in mind that all pelvic floor surgeries do not use the same amount of mesh material and different procedures have different risks associated with them. One retrospective study (Cohen, 2015) addressing incidence of mesh extrusion categorized 576 subjects into three categories: pubo-vaginal sling (PVS) (a small string of mesh around the urethra specifically addressing stress urinary incontinence only); PVS and anterior repair (also referred to as cystocele or bladder prolapse); and PVS with anterior and/or posterior repairs (also referred to as rectocele or rectal prolapse). Mesh extrusion for these types of procedures occurred at the follow rates: approximately 6% for PVS subjects, 15% for PVS + anterior repair, and 11% for PVS + anterior and/or posterior repair. This study did not account for any other types of mesh-related complications.

Pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence make up some of the most common conditions for which patients seek Pelvic Floor physical therapy and perhaps this will allow us to better speak to current research on surgical options.

1. Barski D, Deng EY. Management of Mesh Complications after stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolaps repair: review and analysis of the current literature. Biomed Research International; 2015Article ID 831285.

2. Deng T. et al. Risk factor for mesh erosion after female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU International. Doi:10.1111/bju.13158.

3. Huang LY, et al. Medium-term comparison of uterus preservation versus hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse treatment with prolift mesh. International Urogynecology Journal. 2015;26(7):1013-20.

4. Farthmann J, et al. Functional outcome after pelvic floor reconstructive surgery with or without concomitant hysterectomy. Archives of Gynec and Obstet. 2015; 291(3):573-7.

5. Cohen S, Kaveler E. The incidence of mesh extrusion after vaginal incontinence and pelvic floor prolapse surgery. J of Hospital Admin. 2014; 3(4): www.sciedu.ca/jha.

After menopause, more than half of women may have vulvovaginal symptoms that can impact their lifestyle, emotional well-being and sexual health. What's more, the symptoms tend to co-exist with issues such as prolapse, urinary and/or bowel problems. But unfortunately many women aren't getting the help they need, despite a growing body of evidence that skilled pelvic rehab interventions are effective in the management of bladder/bowel dysfunctions, POP, sexual health issues and pelvic pain.

Vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, disrupted sleep, and weight gain have been listed as the top five symptoms experienced by postmenopausal women in North America and Europe, according to a study by Minkin et al 2015, and they also concluded ‘The impact of postmenopausal symptoms on relationships is greater in women from countries where symptoms are more prevalent.’

Vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, disrupted sleep, and weight gain have been listed as the top five symptoms experienced by postmenopausal women in North America and Europe, according to a study by Minkin et al 2015, and they also concluded ‘The impact of postmenopausal symptoms on relationships is greater in women from countries where symptoms are more prevalent.’

Between 17% and 45% of postmenopausal women say they find sex painful, a condition referred to medically as dyspareunia. Vaginal thinning and dryness are the most common cause of dyspareunia in women over age 50. However pain during sex can also result from vulvodynia (chronic pain in the vulva, or external genitals) and a number of other causes not specifically associated with menopause or aging, particularly orthopaedic dysfunction, which the pelvic physical therapist is in an ideal position to screen for.

According to the North America Menopause Society, ‘…beyond the immediate effects of the pain itself, pain during sex (or simply fear or anticipation of pain during sex) can trigger performance anxiety or future arousal problems in some women. Worry over whether pain will come back can diminish lubrication or cause involuntary—and painful—tightening of the vaginal muscles, called vaginismus. The result can be a vicious circle, again highlighting how intertwined sexual problems can become.’

The research has demonstrated that the optimal strategy for post-menopausal stress incontinence is a combination of local hormonal treatment and pelvic floor muscle training – the strategy of combining the two approaches has been shown to be superior to either approach used individually (Castellani et al 2015, Capobianco et al 2012) and similar conclusions can be drawn for promoting sexual health peri- and post-menopausally.

The pelvic rehab specialist may be called upon to screen for orthopaedic dysfunction in the spine, hips or pelvis, to discuss sexual ergonomics such as positioning or the use of lubricant as well as providing information and education about sexual health before, during and after menopause.

To learn more about sexual health and pelvic floor function/dysfunction at menopause, join me in Atlanta in March for Menopause: A Rehab Approach!

Prevalence of postmenopausal symptoms in North America and Europe, Minkin, Mary Jane MD, NCMP1; Reiter, Suzanne RNC, NP, MM, MSN2; Maamari, Ricardo MD, NCMP3, Menopause:November 2015 - Volume 22 - Issue 11 - p 1231–1238

Low-Dose Intravaginal Estriol and Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in Post-Menopausal Stress Urinary Incontinence, Castellani D. · Saldutto P. · Galica V. · Pace G. · Biferi D. · Paradiso Galatioto G. · Vicentini C., Urol Int 2015;95:417-421

Unfortunately one of the most common things we hear in pelvic rehab is “I hope you can help me, you’re my last hope.” In severe cases, this translates to the patient having little hope of surviving their life with pelvic pain. In severe but not necessarily life-threatening cases, being a patient’s last hope can also mean “please help me have sex in my relationship or my partner is going to leave me.” This situation places a lot of pressure on the patient and also on the therapist. How long did it take this patient to find her way to pelvic rehab? Research tells us that most women have been through multiple physicians, under- or misdiagnosed, and that many have failed attempts at intervention with medications or procedures.

It’s clear to women that they are being judged when they go to medical appointments complaining of pelvic pain or pain with intercourse. Although it seems really old school to hear that a provider said “It’s all in your head.” or “How much do you like your partner?” or “Well, you’re getting older, sex isn’t that important.” these dismissive phrases are still used. A study by Nguyen et al., 2013 reported that women who reported chronic pain were more likely to perceive being stereotyped by doctors and others. Interestingly, among the group of women who had chronic vulvar pain, the women who sought care for their condition reported feeling more stigmatized. Because the support a woman perceives may influence her willingness to seek out help for chronic vulvar pain, we need to keep educating our peers, the public, and the providers about the real challenges women face, and the power of rehabilitation in overcoming those challenges.

It’s clear to women that they are being judged when they go to medical appointments complaining of pelvic pain or pain with intercourse. Although it seems really old school to hear that a provider said “It’s all in your head.” or “How much do you like your partner?” or “Well, you’re getting older, sex isn’t that important.” these dismissive phrases are still used. A study by Nguyen et al., 2013 reported that women who reported chronic pain were more likely to perceive being stereotyped by doctors and others. Interestingly, among the group of women who had chronic vulvar pain, the women who sought care for their condition reported feeling more stigmatized. Because the support a woman perceives may influence her willingness to seek out help for chronic vulvar pain, we need to keep educating our peers, the public, and the providers about the real challenges women face, and the power of rehabilitation in overcoming those challenges.

Vulvodynia is a common pelvic pain condition, and one that typically is associated with painful intercourse, or dyspareunia. (Arnold et al., 2006) It's estimated that by the age of 40, as many as 8% of women will have or have had a diagnosis of vulvodynia (Harlow et al., 2014), and this is clearly a significant quality of life issue.

Physical therapy has been shown to be successful in treating vulvar pain and pain with intercourse, including as part of a multidisciplinary approach. (Brotto et al., 2015) That's why Herman & Wallace is so eager to help empower more therapists to help patients live a life free of vulvar pain and dyspareunia. You can learn more about our courses and other resources at https://www.hermanwallace.com/continuing-education-courses.

Arnold, L. D., Bachmann, G. A., Kelly, S., Rosen, R., & Rhoads, G. G. (2006). Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with co-morbidities and quality of life. Obstetrics and gynecology, 107(3), 617.

Brotto, L. A., Yong, P., Smith, K. B., & Sadownik, L. A. (2015). Impact of a multidisciplinary vulvodynia program on sexual functioning and dyspareunia. The journal of sexual medicine, 12(1), 238-247.

Harlow, B. L., Kunitz, C. G., Nguyen, R. H., Rydell, S. A., Turner, R. M., & MacLehose, R. F. (2014). Prevalence of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia: population-based estimates from 2 geographic regions. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 210(1), 40-e1.

Nguyen, R. H., Turner, R. M., Rydell, S. A., MacLehose, R. F., & Harlow, B. L. (2013). Perceived stereotyping and seeking care for chronic vulvar pain. Pain Medicine, 14(10), 1461-1467.

Since the passing of Title IX in 1972, which protects people from sex discrimination in education or activity programs receiving federal funding, the number of females participating in sports has greatly increased. The National Federation of State High School Associations states that in 2011 nearly 3.2 million girls are participating in high school sports.

Unfortunately, a consequence of this increased participation in sports is a higher prevalence in urinary incontinence (UI) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in female athletes. Borin et al looked at the ability of nulliparous female athletes to generate intracavity perineal pressure in comparison to nonathletic women. The study demonstrated that higher mean pressures were generated by nonathletic women in comparison to the athletic women group and that lower perineal pressures in the athletic women were also related to number of games per year and time spent on sport specific workouts and strength training workouts.

UI and SUI are underreported in the general population and also in the athletic population. As health care professionals it is important to screen for UI and SUI in our clients. Physical therapy interventions using pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation have shown to decrease the severity of UI and SUI (Rivalta et al, Hulme). Rivalta used internal methods to improve the function of the pelvic floor muscle. Hulme’s success was achieved through activation of the pelvic floor muscles’ extrinsic synergists.

|

|

Pilates is often used in physical therapy as a therapeutic tool to improve lumbar stability with studies showing increases in abdominal strength (Sekendiz), trunk extensor endurance (Sekendiz) and to improve posture (Kloubec). Pilates is often also used in pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation and can easily be modified for low level clients. For example the use of resistance can assist supporting the weight of the leg. Practical proof, while lying supine in neutral lumbar spine position, stretch an arm and a leg away from center, notice the difficulty to maintain neutral spine. Now hold a resistance strap, which is also attached to the foot, and notice how maintaining neutral lumbar spine is easier to maintain (pictured above).

Pilates can also be modified for the higher level client or more athletic client. The use of arc barrels, BOSUs or the Hooked on Pilates MINIMAX (pictured belowy) allow the athletic client to achieve an inverted position, unloading the pelvic floor muscles. In the inverted position, pelvic floor muscles may be activated as intrinsic and/or extrinsic synergists of the pelvic floor muscles are also activated. These types of exercises may be more appealing to the athletic client ensuring continuation of the exercise post discharge from physical therapy.

|

|

Borin LC, Nunes FR, Guirro EC. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle pressure in female athletes. PMR. 2013; 5(3):189-193.

Hulme, Janet. Beyond Kegels 3rd edition, 2012 Phoenix Publishing Co. Missoula, Montana

Kloubec JA. Pilates for improvement of muscle endurance, flexibility, balance and posture. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:661-667.

Rivalta M, Sughunolfi MC, Micali S, De Stafani S, Torcasio F, Bianchi G, Urinary incontinence and sport. First and preliminary experience with a combined pelvic floor rehabilitation program in three female athletes. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(5);330-334.

Sekendiz B, Altun O, Korkusuv F, Akin S, Effects of pilates exercise on trunk strength, endurance and flexibility in sedentary adult females. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2005;9:52-57.