Leg length discrepancy (LLD) is when there is a noticeable difference in length of one leg to the other. LLD is common and can be found in 70% of the population (Gurney, 2002). LLD can be structural or functional. Structural LLD is when a long bone in the leg is longer or shorter than the other. Structural LLD is often the result of congenital or boney damage of epiphyseal plate. Functional is when there is an apparent LLD from higher in the chain such as scoliosis. Generally as pelvic floor therapists we are orthopedic based therapists. In physical therapy school we learned that a leg length discrepancy had to be >1 cm to be considered significant, and based off of recent research that is still the case. Research in the last few years has focused on whether LLD has an effect on age related changes with osteoarthritis, posture & gait, and pain. Physiopedia suggests differential diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction, scoliosis, low back pain, iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome, stress fractures, and pronation. It can often feel like a chicken or egg question.

In the clinic I typically screen for a leg length discrepancy during my initial evaluation. A LLD may be noticed upon observation of gait assessment, standing posture, or part of the pelvic obliquity screen in standing and then in supine.

In the clinic I typically screen for a leg length discrepancy during my initial evaluation. A LLD may be noticed upon observation of gait assessment, standing posture, or part of the pelvic obliquity screen in standing and then in supine.

During gait, a LLD will create bilaterteral gait impairments. Khamis et al did a systematic review of LLD and gait deviations in 2017. They narrowed the search down to 12 articles and found that LLD >1cm was significantly related to gait deviations. These deviations occurred bilaterally, and while initially compensations occurred in the sagittal plane, as the LLD increased so did the gait deviations, and then affected frontal planes of motion as well. Resende et al (2016) agrees that even mild LLD should not be overlooked. They found that the most likely gait deviations were also in the sagittal planes and consisted of rearfoot and ankle dorsiflexion and inversion, knee flexion and adduction, hip adduction and flexion, and pelvic trendelenburg.

The sagittal, or right/left plane, and frontal, or front/back, plane involvement is consistent with the differential diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction, low back pain, and pronation. Really, one could justify why a LLD could contribute to pain and dysfunction in most of the lower body. It is reasonable to think that these compensational moments in gait over a long period create boney changes in the lower extremities which may contribute to low back pain.

Clinically, a leg length discrepancy can be assessed directly with a tape measure or indirectly with a shoe lift. Badii (2014) found a higher interrater reliability with the indirect method of a shoe lift as opposed to measuring with a tape measure.

Rannisto et al (2019) looked at leg length discrepancy among meat cutters with low back pain. All participants had been working for 10 years and were greater than 35 years old. Participants needed to have a LLD of 5mm (5mm is 0.5 cm) or more and complain of low back pain of >2/10 on visual analog scale (VAS). They were all given insoles and randomized into 2 groups; the intervention group were given lifts to correct the LLD about 70%; for example a 10mm LLD was corrected to 3 mm. The LLD was measured with a laser ultrasound technique. Participants were followed for 12 months. The intervention group had improvement in low back pain intensity, sciatica intensity, and took less sick time. Possibly the most amazing part is that for those that wore the heel lift at work the compliance was good.

Leg length discrepancy can often be an underlying component contributing to complaints of pain and dysfunction. It may have more of an effect on the populations who stand or walk for most of their work, and I wonder as more people transition to standing desks if we will see more people come into the clinic with a previously undiagnosed LLD.

My biggest clinical pearls from this research is that:

- Heel lifts can be used to diagnose and then for treatment (yay! One less step of getting the tape measure out)

- The heel lift does not have to be perfect. Clinically, I will try a lift and have the person walk, and then we can make a team decision if this lift is enough and feels better

- The gait compensations are consistently adduction and internal rotation throughout the lower body chain. I will continue to work on the opposing muscle groups; lateral rotators, hip extensors and abductors.

Leg Length Discrepancy can be evaluated using various assessments. To learn orthopedic evaluative techniques for patients, consider joining Lila Abbate in her course Advanced Orthopedic Assessment for the Pelvic Health Therapist.

Maziar Badii, A Nicole Wade, David R Collins, Savvakis Nicolaou, B Jacek Kobza, Jacek A Kopec, Comparison of lifts versus tape measure in determining leg length discrepancy; Journal of Rheumatology 2014, 41 (8): 1689-94

Renan A. Resende, Renata N. Kirkwood, Kevin J. Deluzio, Silvia Cabral, Sérgio T. Fonseca. "Biomechanical strategies implemented to compensate for mild leg length discrepancy during gait" Gait & Posture, Volume 46, 2016; 147-153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.03.012

Sam Khamis, Eli Carmeli, Relationship and significance of gait deviations associated with limb length discrepancy: A systematic review, Gait & Posture, Volume 57, 2017, 115-123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.05.028

Burke Gurney, Leg length discrepancy, Gait & Posture, Volume 15, Issue 2, 2002, Pages 195-206, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00148-5.

Satu Rannisto, Annaleena Okuloff, Jukka Uitti, et al. Correction of leg-length discrepancy among meat cutters with low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2019;(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2478-3.

Diagnosing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction can be tricky. Therapists need to rule out lumbar spine and the hip, and sometimes there is more than one area causing pain and limiting functional mobility. Typically, ruling in SIJ dysfunction is done by pain provocation tests and load transfer tests. Once the SIJ has been ruled in, then therapists can use a variety of treatments. Often those treatments include therapeutic exercise, joint manipulation, and Kinesio tape. But which intervention is the most effective?

A recent study looked at three physical therapy interventions for treatment for SIJ (sacroiliac joint) dysfunction and assessed which was the most effective (Al-Subahi, M 2017). The authors did a systematic review of the literature. The articles were from 2004-2014, written in English, with male and female participants. This review included a variety of experiment types from randomized control trials to case studies. Of the 1114 studies, only 9 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Four of the nine studies used manipulation, three used Kinesio Tape, and the three used exercise. One study did both exercise and manipulation, and was looked at in both interventions. All categories had at least one randomized control trial.

For the manipulation intervention, all studies showed a decrease in pain and disability at follow up. The follow ranged from 3 to 4 days to 8 weeks. Disability was measured using the Oswestry Disability Index. One study did manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation to lumbar and SIJ manipulation and showed improvement with manipulation to SIJ or SIJ and lumbar. The review did not disclose the type of lumbar manipulation, but did state the SIJ manipulation was a side bend and rotation position with an inferior and lateral force to ASIS (anterior superior iliac spine). Another study did either a SIJ manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation or a mechanical force with manual assistance. One studied did manipulation and home exercises but did not record exercise interventions. The last study did the same SIJ manual high velocity and low amplitude thrust manipulation as in previous study combined with exercise. The exercises are mentioned below.

For the exercise intervention, the studies did primarily stabilization exercises that were either isometric or isotonic eccentric or concentric. Quick PT school review, in isometric exercises the muscle does not change length, while in isotonic eccentric exercises the muscle is being lengthened under load, and isotonic concentric is the muscle shortening under load. All three studies showed decrease in pain. The first study had 7 participants and combined manipulation and exercise. The exercises consisted of 12% max voluntary contraction and eccentric loading quads in supine with hips at 90 degrees, and concentrically loading hamstrings in prone. The second study was a case study and performed 8 lumbo-pelvic-femoral stabilization exercises for 8 weeks. Fun fact: this case study was written by my Therapeutic Exercise teacher in PT school who did a lot of Postural Restoration based exercises. The last study, had 22 participants and educated and provided exercises on deep abdominal and multifidus muscles and do complete these exercises during functional movements throughout the day. These participants were follow up a year later and had decreased pain compared to laser group.

For the Kinesio tape (Kinesio tape) intervention, the studies did not find that Kinesio tape was not an effective intervention, however the follow up ranged from immediately after applying tape to 4 weeks afterwards. In the first study, a randomized controlled trial with 60 participants, the Kinesio tape was applied in sitting with 25% tension of 4 strips making a star pattern over the point of maximal pain. The Kinesio tape was compared to placebo tape and showed equal improvement in pain and disability. The other two studies applied a different taping technique where the Kinesio tape was applied. One applied the tape over erector spinae and internal oblique muscles bilaterally and in the other study the Kinesio tape was applied with 25% tension over external obliques, a second strip was placed from ASIS to PSIS in side-lying, and then a third strip was placed along rectus abdominis muscle. In this same study the tape was applied for weeks (6x/week for 9 hours/day).

In summary, the authors note that all three interventions help decrease pain and disability in women and men with SIJ dysfunction. The authors suggest that manipulation may be the most effective. Kinesio tape showed no significant difference between placebo tape. Exercise was effective, but less so than manipulation.

This review has a lot of limitations. The variety of experiment types with varying degrees of evidence, small number of participants, and lack of blinding. Most studies had a limited follow up ranging from 3-4 days to 12 months. The outcome measures varied greatly. Most studies had pain scores as the outcome measure, though one study only used inclination meter of anterior pelvic tilt. Use of a consistent objective measure in addition to perceived pain and disability would have helped. Only 1 study did pain provocation tests and that study was a case study whose intervention focused on Kinesio-taping.

As physical therapists we want to provide effective evidence-based practice, and we want to provide individualized compassionate care. It is hard to make a direct line between this study’s recommendations and clinical application based on the numerous limitations. I agree with the authors that manipulation and exercise are bread and butter to physical therapists. I disagree about Kinesio tape not being an effective treatment. Is Kinesio tape going to create boney alignment changes? Likely not. Is Kinesio tape (or any other tape) going to give proprioceptive feedback and possibly help calm sensory pathways? Yes. If a patient likes being taped, and thinks it will help, then I will tape them. Even if taping is just placebo effect; it’s still an effect.

Al-Subahi, M., Alayat, M., Alshehr, M.A., et al. (2017) The effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: A systematic review. J Phys. Ther. Sci. 29: 1689-1694.

Does cognitive self-regulation influence the pain experience by modulating representations of nociceptive stimuli in the brain or does it regulate reported pain via neural pathways distinct from the one that mediates nociceptive processing? Woo and colleagues devised an experiment to answer this question.1 They invited thirty-three healthy participants to undergo fMRI while receiving thermal stimulation trial runs that involved 6 levels of temperatures. Trial runs included “passive experience” where participants passively received and rated heat stimuli, and “regulation” runs, where participants were asked to cognitively increase or decrease pain intensity.

Instructions for increasing pain intensity included statements such as “Try to focus on how unpleasant the pain is. Pay attention to the burning, stinging and shooting sensation.” Instructions for decreasing pain intensity included statements such as “Focus on the part of the sensation that is pleasantly warm. Imagine your skin is very cool and how good the stimulation feels as it warms you up.” The effects of both manipulations on two brain systems previously identified in the literature were examined. One brain system was the “neurological pain signature” (NPS), a distributed pattern of fMRI activity shown to specifically track pain intensity induced by noxious inputs. The second system was the pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) with the nucleus accumbens (NAc), shown to play a role in both reappraisal and modulation of pain. In humans, the vmPFC tracks spontaneous pain when it has become chronic and potentially dissociated from nociception.2,3 In patients with sub-acute back pain, the vmPFC-NAc connectivity has been shown to predict subsequent transition to chronic back pain.4 In addition, the vmPCF is hypothesized to play a role in the construction of self-representations, assigning personal value to self-related contents and, ultimately, influencing choices and decisions.5

Instructions for increasing pain intensity included statements such as “Try to focus on how unpleasant the pain is. Pay attention to the burning, stinging and shooting sensation.” Instructions for decreasing pain intensity included statements such as “Focus on the part of the sensation that is pleasantly warm. Imagine your skin is very cool and how good the stimulation feels as it warms you up.” The effects of both manipulations on two brain systems previously identified in the literature were examined. One brain system was the “neurological pain signature” (NPS), a distributed pattern of fMRI activity shown to specifically track pain intensity induced by noxious inputs. The second system was the pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) with the nucleus accumbens (NAc), shown to play a role in both reappraisal and modulation of pain. In humans, the vmPFC tracks spontaneous pain when it has become chronic and potentially dissociated from nociception.2,3 In patients with sub-acute back pain, the vmPFC-NAc connectivity has been shown to predict subsequent transition to chronic back pain.4 In addition, the vmPCF is hypothesized to play a role in the construction of self-representations, assigning personal value to self-related contents and, ultimately, influencing choices and decisions.5

Woo and colleagues found that both heat intensity and self-regulation strongly influenced reported pain, however they did so by two differing pathways. The NPS mediated only the effects of nociceptive input. The self-regulation effects on pain were mediated by the NAc-vmPFC pathway, which was unresponsive to the intensity of nociceptive input. The NAc-vmPFC pathway responded to both “increase” and “decrease” self-regulation conditions. Based on these results, study authors suggest that pain is influenced by both noxious input and cognitive self-regulation, however they are modulated by two distinct brain mechanisms. While the NPS encodes brain activity closely tied to primary nociceptive processing, the NAc-vmPFC pathway encodes information about evaluative aspects of pain in context. This research is limited in that the distinction between pain intensity and pain unpleasantness was not included and the subjects were otherwise healthy. Further research is warranted on the effects of this cognitive self-regulation model on brain pathways in patients with chronic pain conditions.

Even with the noted limitations, this research invites the clinician to consider the role of both nociceptive mechanisms and cognitive self-regulatory influences on a patient’s pain experience and suggests treatment choices should take both factors into consideration. Mindful awareness training is a treatment that contributes to cognitive self-regulatory brain mechanisms.6 When mindful, pain is observed as and labeled a sensation. The term “sensation” carries a neutral valence compared to “pain” which may reflect greater alarm or threat to an individual. The mind is recognized to have a camera lens-like quality that can shift from zoom to wide angle. While pain can draw attention in a more narrow focus on the painful body area, when mindful, an individual can deliberately adopt a wide angle view, focusing on pain free areas and other neutral or positive states. In addition, when mindful, the unpleasant sensation rests in awareness not characterized by fear and distress, but by stability, compassion and curiosity. Patients may not have control over the onset of pain, but with mindfulness training, they can take control over their response to the pain. This deliberate adoption of mindful principles and practices can contribute to cognitive self-regulatory brain mechanisms that can ultimately impact pain perception.

I am excited to share additional research and practical clinical strategies that help patients self-regulate their reactions to pain and other symptoms in my 2019 courses, Mindfulness for Rehabilitation Professionals at University Hospitals in Cleveland OH, April 6 and 7 and Mindfulness-Based Pain Treatment in Houston TX, October 26 and 27 and Portland OR May 18 and 19. Hope to see you there!

1. Woo CW, Roy M, Buhle JT, Wager TD. Distinct brain systems mediate the effects of nociceptive input and self-regulation on pain. PLoS;2015;13(1):e1002036.

2. Baliki MN, Chialvo DR, Geha PY, Levy RM, et al. Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of chronic back pain.J Neurosci. 2006;26(47):12165-73.

3. Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain. 2013;136(pt9):2751-68.

4. Baliki MN, Peter B B, Torbey S, Herman KM, et al. Corticostriatal functional connectivity predicts transition to chronic back pain. Nat Neurosci.2012;15(8):1117-9.

5. D’Argembeau. On the role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in self-processing: The Valuation Hypothesis. Front Human Neurosci. 2013;7:372.

6. Zeidan F, Vago DR. Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: a mechanistic account. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016 Jun;1373(1):114-27.

Dustienne Miller MSPT, WCS, CYT is a Herman & Wallace faculty member, owner of Your Pace Yoga, and the author of the course Yoga for Pelvic Pain. Join her in Columbus, OH this April 27-28, to learn how yoga can be used to treat interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, vulvar pain, coccydynia, hip pain, and pudendal neuralgia. The course is also coming to Manchester, NH September 7-8, 2019, and Buffalo, NY on October 5-6, 2019.

How does a yoga program compare to a strength and stretching program for women with urinary incontinence? Dr. Allison Huang1 et al have published another research study, after publishing a pilot study2 on using group-based yoga programs to decrease urinary incontinence. Well-known yoga teachers Judith Hanson Lasater, PhD, and Leslie Howard created the yoga class and home program structure for this research study and the 2014 pilot study. The yoga program was primarily based on Iyengar yoga, which uses props to modify postures, a slower tempo to increase mindfulness, and pays special attention to alignment.

To be chosen for this study, women had to be able to walk more than 2 blocks, transfer from supine to standing independently, be at least 50 years of age, and experience stress, urge, or mixed urinary incontinence at least once daily. Participants had to be new to yoga and holding off on clinical treatment for urinary incontinence, including pelvic health occupational and physical therapy.

To be chosen for this study, women had to be able to walk more than 2 blocks, transfer from supine to standing independently, be at least 50 years of age, and experience stress, urge, or mixed urinary incontinence at least once daily. Participants had to be new to yoga and holding off on clinical treatment for urinary incontinence, including pelvic health occupational and physical therapy.

28 women were assigned to the yoga intervention group and 28 women were assigned to the control group. The mean age was 65.4 with the age range of 55-83 years of age.

The control group received bi-weekly group class and home program instruction on stretching and strengthening without pelvic floor muscle cuing or relaxation training.

The yoga program met for group class twice a week for 90 minutes each and practiced at home one hour per week. The control group met twice a week for 90 minutes with a one-hour home program every week. Both groups met for 12 weeks.

Both groups received bladder behavioral retraining informational handouts. The information sheets contained education about urinary incontinence, pelvic floor muscle strengthening exercises, urge suppression strategies, and instructions on timed voiding.

The yoga program included 15 yoga postures: Parsvokonasana (side angle pose), Parsvottasana (intense side stretch pose), Tadasana (mountain pose) Trikonasana (triangle pose), Utkatasana (chair pose), Virabhadrasana 2 (warrior 2 pose), Baddha Konasana (bounded angle pose), Bharadvajasana (seated twist pose), Malasana (squat pose), Salamba Set Bandhasana (supported bridge pose), Supta Baddha Konasana (reclined cobbler’s pose), Supta Padagushthasana (reclined big toe pose), Savasana (corpse pose), Viparita Karani Variation (legs up the wall pose), and Salabhasana (locust pose).

Women in the yoga intervention group reported more than 76% average improvement in total incontinence frequency over the 3-month period. Women in the muscle stretching/strengthening (without pelvic floor muscle cuing and relaxation training) control group reported more than 56% reduction in leakage episodes.

Stress urinary incontinence episodes decreased by an average of 61% in the yoga group and 35% in the control group (P = .045). Episodes of urge incontinence decreased by an average of 30% in the yoga group and 17% in the control group (P = .77).

The take away? We know behavioral techniques have been shown to improve quality of life and decrease frequency and severity of urinary incontinence episodes.3 Couple this with our clinical interventions, and our patients have a way to reinforce the work we do in the clinic by themselves, or socially within their community. Yoga can be another tool in the toolbox for optimizing pelvic health.

1) Diokno AC et al. (2018). Effect of Group-Administered Behavioral Treatment on Urinary Incontinence in Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med.1;178(10):1333-1341. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3766.

2) Huang, Alison J. et al. (2019). A group-based yoga program for urinary incontinence in ambulatory women: feasibility, tolerability, and change in incontinence frequency over 3 months in a single-center randomized trial. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 220(1) 87.e1 - 87.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.031

3) Huang, A. J., Jenny, H. E., Chesney, M. A., Schembri, M., & Subak, L. L. (2014). A group-based yoga therapy intervention for urinary incontinence in women: a pilot randomized trial. Female pelvic medicine & reconstructive surgery, 20(3), 147-54.

When It Comes to Bone Building Activities for Osteoporosis, there’s Weight Bearing and then there’s Weight Bearing!

Ask just about anyone on the street what one should do for osteoporosis and the typical answer is- weight bearing exercises. And they would be partially right. Weight bearing, or loading activities have been shown to increase bone density.1 But that’s not the whole story.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

An alternative is to focus on “odd impact” loading. A study by Nikander et al 2 targeted female athletes in a variety of sports classified by the type of loading they apparently produce at the hip region; that is, high-impact loading (volleyball, hurdling), odd-impact loading (squash-playing, soccer, speed-skating, step aerobics), high magnitude loading (weightlifting), low-impact loading (orienteering, cross-country skiing), and non-impact loading (swimming, cycling). The results showed high-impact and odd-impact loading sports were associated with the highest bone mineral density.

Morques et al, in Exercise Effects on Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, found that odd impact has potential for preserving bone mass density as does high impact in older women. Activities such as side stepping, figure eights, backward walking, and walking in square patterns help “surprise the bones” due to different angles of muscular pull on the hip. The benefit, according to Nikander, is that we can get the same osteogenic benefits with less force; moderate versus high impact. This type of bone training would offer a feasible basis for targeted exercise-based prevention of hip fragility. I tell my osteoporosis patients that if they walk or run the same route, the same distance, and the same speed that they are not maximizing the osteogenic benefits of weight bearing. Providing variety to the bones creates increased bone mass in the femoral neck and lumbar spine.4

Dancing is another great activity which combines forward, side, backward, and diagonal motions to movement. In addition, it adds music to make the “weight bearing exercises” more fun. Due to balance and fall risk many senior exercise classes offer Chair exercise to music. Unfortunately sitting is the most compressive position for the spine and is particularly problematic with osteoporosis patients. Also the hips do not get any weight bearing benefit. Whenever safely possible, have patients stand; you can position two kitchen chairs on either side, much like parallel bars, to hold on to while they “dance.”

Providing creativity in weight bearing activities using odd impact allows not only for fun and stimulation; it also offers more “bang for the buck!”

- Mosekilde L. Age-related changes in bone mass, structure, and strength--effects of loading. Z Rheumatol (2000); 59 Suppl 1:1-9.

- Nikander et al. Targeted exercises against hip fragility. Osteoporosis International (2009)

- Marques et al. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Epub 2011 Sep 16

- Weidauer L. et al. Odd-impact loading results in increased cortical area and moments of inertia in collegiate athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol (2014)

Andrea Wood, PT, DPT, WCS, PRPC is a pelvic health specialist at the University of Miami downtown location. She is a board certified women’s health clinical specialist (WCS) and a certified pelvic rehabilitation practitioner (PRPC). She is passionate about orthopedics and pelvic health. In her spare time, you can find her enjoying the south Florida outdoors.

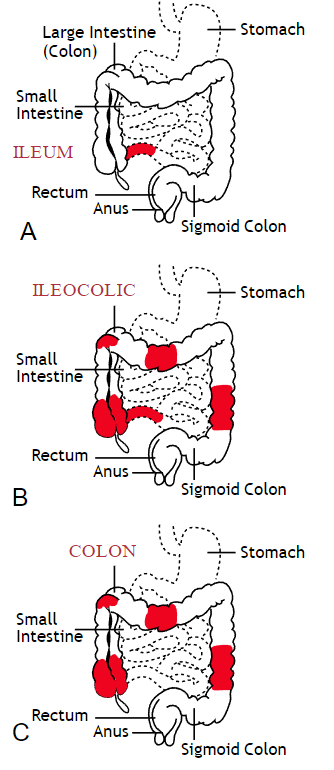

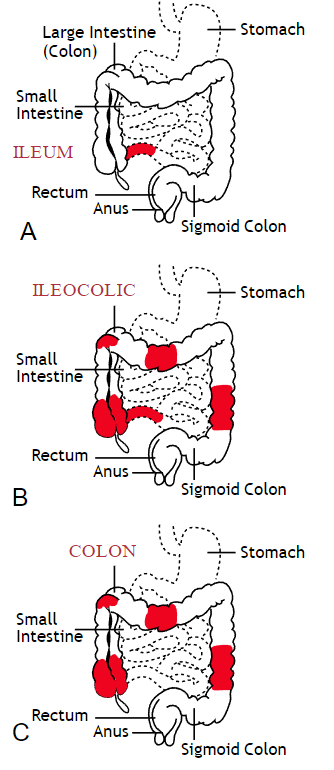

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes the two diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. While both can cause similar health effects, the differences of the disease pathologies are listed below:1

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease | |

| Affected Area |

|

|

| Pattern of Damage |

|

|

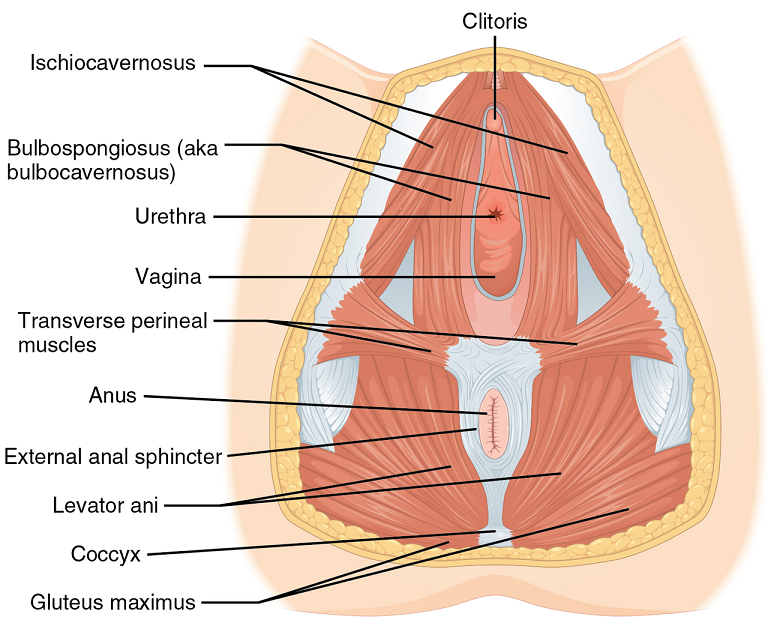

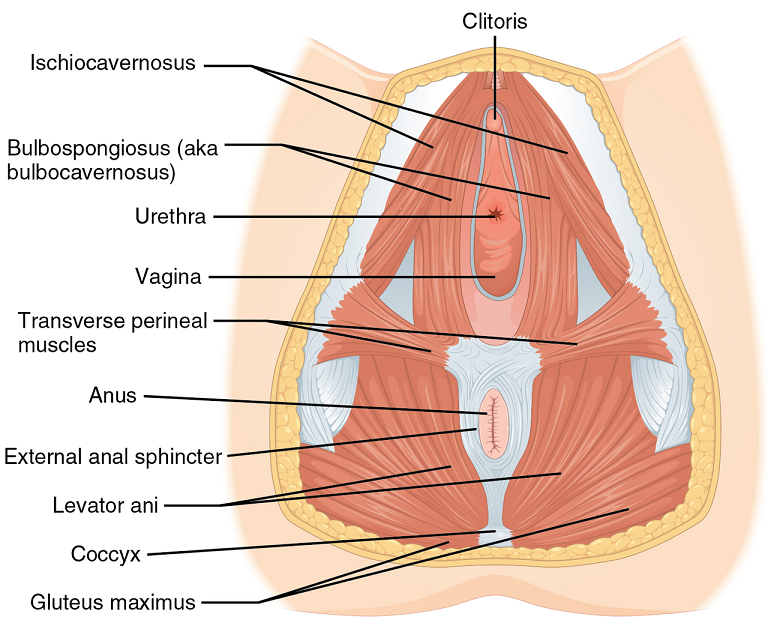

Common complications experienced by patients with IBD include fecal incontinence, fecal urgency, night time soiling, urinary incontinence, abdominal pain, hip and core weakness, pelvic pain, fatigue, osteoporosis, and sarcopenia. In a sample of 1,092 patients with Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, or unclassified IBD, 57% reported fecal incontinence. Fecal incontinence was reported not only during periods of flare ups, but also during remission periods.2 One common factor affecting fecal incontinence is external anal sphincter fatigue. External anal sphincter fatigue has also been shown to be present in IBD patients who are not experiencing fecal incontinence or fecal urgency. IBD patients have been shown in studies to have similar baseline pressures versus healthy matched controls, thus indicating the possibility that deficits in endurance versus strength can play a larger role in fecal incontinence.3 Other factors contributing to fecal incontinence include post inflammatory changes that may alter anorectal sensitivity, anorectal compliance, neuromuscular coordination, and cause visceral hypersensitivity. Visceral hypersensitivity may be caused by continuous release of inflammatory mediators found in patients with IBD. It is also important to screen properly for incomplete bowel emptying and stool consistency to rule out overflow diarrhea or fecal impaction. Reports of need to splint digitally for full evacuation may indicate incomplete bowel emptying and defaectory disorders such as paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle or rectocele. Anorectal manometry testing may be highly useful in identifying patients likely to improve from biofeedback therapy.4

Urinary incontinence can also be another secondary consequence to IBD. In a sample of 4,827 patients with IBD, 1/3 of responders reported urinary incontinence that was strongly associated with the presence of fecal incontinence. Frequent toilet visits for defecation may stimulate overactive bladder. Women were more likely to experience fecal incontinence versus men. One possible mechanism for increased fecal incontinence in women is men often have a longer and more complete anal sphincter that may be protective of fecal incontinence.5

Physical activity has been shown to be lower in patients with IBD versus healthy controls. 6, 7 Guiding IBD patients in proper exercises programs can have great benefits. Exercise may reduce inflammation in the gut and maintain the integrity of the intestines, reducing inflammatory bowel disease risk.8 It can also help increase bone mass density, an important factor in IBD patients who are at greater risk for osteoporosis. It has also been shown to help general fatigue in IBD patients. Patients with Crohn’s disease who participate in higher exercise levels may be less likely to develop active disease at 6 months. Treadmill training at 60% VO2 max and running three times a week has not been shown to evoke gastrointestinal symptoms in IBD patients. An increase of BMI predicts poorer outcomes and shorter time to first surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease.6

Conservative physical therapy interventions for treating IBD symptoms can include the following:

| Symptoms resulting from IBD | Physical Therapy Interventions |

| Fecal Incontinence (FI) |

|

| Urinary urgency |

|

| Sarcopenia |

|

| Fatigue |

|

| Pelvic Pain |

|

Surgical interventions for IBD are dependent upon what type of disease the patient has and what areas of the intestines are affected the most. Surgery may be considered once the disease has become non responsive to medication therapy and quality of life continues to decline. A colectomy involves removing the colon while a proctocolectomy involves both removal of the colon and rectum. For ulcerative colitis patients, options include total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy or a restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Restorative proctocolectomy eliminates the need for an ostomy bag making it the preferred surgery of choice if possible and gold standard for ulcerative colitis patients.10 For patients with Crohn’s disease, options include resection of part of the intestines followed by an anastomosis of the remaining healthy ends of the intestines, widening of the narrowed intestine in a procedure called a strictureplasty, colectomy or proctocolectomy, fistula repair, and removal of abscesses if needed.11

1. Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. 2019. What is Crohn’s Disease. Retrieved from: http://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-are-crohns-and-colitis/what-is-crohns-disease/

2. Vollebregt PF, van Bodegraven A, Markus-de Kwaadsteniet T, et al. Impacts on perianal disease and faecal incontinence on quality of life and employment in 1092 patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2018; 47: 1253-1260

3. Athanasios A, Kostantinos H, Tatsioni A et al. Increased fatigability of external anal sphincter in inflammatory bowel disease: significance in fecal urgency and incontinence. J Crohns Colitis (2010) 4: 553-560.

4. Nigam G, Limdi J, Vasant D. Current perspectives on the diagnosis and management of functional anorectal disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018 Dec 6: doi: 10.1177/1756284818816956

5. Norton C, Dibley L, Basset P. Faecal incontinence in inflammatory bowel disease: Associations and effect on quality of life. J Crohn’s Colitis. (2013) 7, e302-e311.

6. Biliski J, Mazur-Bialy A, Brzozowski B et al. Can exercise affect the course of inflammatory bowel disease? Experimental and clinical evidence. Pharmacological Reports. 2016 (68): 827-836.

7. Tew G, Jones K, Mikocka-Walus A. Physical activity habits, limitations, and preditors in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a large cross-sectional online survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22(12): 2933-2942.

8. Vincenzo M, Villano I, Messina A. Exercise modifies the gut microbiota with positive health effects. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevitiy. 2017: Article ID 3831972.

9. Cramer H, Schafer M, Schols M. Randomised clinical trial: yoga vs written self care advice for ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 45: 1379-1389.

10. Cornish J, Wooding K, Tan E, et al. Study of sexual, urinary, and fecal function in females following restorative proctocolectomy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 18 (9) 2012. 1601-160

11. Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. 2019. Surgery Options. Retrieved from: http://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-are-crohns-and-colitis/what-is-crohns-disease/surgery-options.html

Today's guest post comes from Kelsea Cannon, PT, DPT, a pelvic health practitioner in Seattle, WA. Kelsea graduated from Des Moines University in 2010 and practices at Elizabeth Rogers Pilates and Physical Therapy.

Many studies done on pelvic floor muscle training largely have subjects who are Caucasian, moderately well educated, and receive one-on-one individualized care with consistent interventions. This led a group of researchers to investigate the occurrence of pelvic floor dysfunction, specifically pelvic organ prolapse (POP), in parous Nepali women. These women are known to have high incidences of POP and associated symptomology. Another impetus to perform this research: the discovery that there was a major lack of proper pelvic floor education for postpartum women. These women were commonly encouraged to engage their pelvic floor muscles via performing supine double leg lifts, sucking in their tummies/holding their breath/counting to ten, and squeezing their glutes. These exercises would be on a list of no-no’s here in the United States. In 2017, Delena Caagbay and her team of researchers discovered that in Nepal, no one really knew the correct way to teach proper pelvic floor muscle contractions, preventing the opportunity for women to better understand their pelvic floors. The team then set out to investigate the needs of this population, with the eventual goal of providing effective pelvic floor education for Nepali women.

Caagbay and her team first wanted to know what baseline muscle activity the Nepali women had in their pelvic girdle. Physical examinations and internal pelvic floor muscle strength assessments revealed that surprisingly there was a low prevalence of pelvic floor muscle defects, such as levator avulsions and anal sphincter trauma. Uterine prolapses were most common while rectoceles were comparatively less common. Their muscles were also strong and well-functioning, often averaging a 3/5 on the Modified Oxford Scale. It was hypothesized that these women had low prevalence of muscle injury because instruments were not commonly used during childbirth, they had lower birth weight babies, and the women were typically younger when giving birth (closer to 20-21 years old). But they had a high prevalence of POP even with good muscle tone? Researchers suggested that their incidence of POP is likely stemming from their sociocultural lifestyle requirements, as women are left to do most of the daily household chores and caregiving tasks while men often travelled away from the home to perform paid labor. Physical responsibilities for these women commonly begin at younger ages and while it helps promote good muscle tone, the heavier loading places pressure on the connective tissue and fascia that support the pelvic organs. Because of the demands of their lifestyles, Nepali women are often forced to return to their physically active state within a couple weeks after giving birth.

Caagbay and her team first wanted to know what baseline muscle activity the Nepali women had in their pelvic girdle. Physical examinations and internal pelvic floor muscle strength assessments revealed that surprisingly there was a low prevalence of pelvic floor muscle defects, such as levator avulsions and anal sphincter trauma. Uterine prolapses were most common while rectoceles were comparatively less common. Their muscles were also strong and well-functioning, often averaging a 3/5 on the Modified Oxford Scale. It was hypothesized that these women had low prevalence of muscle injury because instruments were not commonly used during childbirth, they had lower birth weight babies, and the women were typically younger when giving birth (closer to 20-21 years old). But they had a high prevalence of POP even with good muscle tone? Researchers suggested that their incidence of POP is likely stemming from their sociocultural lifestyle requirements, as women are left to do most of the daily household chores and caregiving tasks while men often travelled away from the home to perform paid labor. Physical responsibilities for these women commonly begin at younger ages and while it helps promote good muscle tone, the heavier loading places pressure on the connective tissue and fascia that support the pelvic organs. Because of the demands of their lifestyles, Nepali women are often forced to return to their physically active state within a couple weeks after giving birth.

After assessing the current needs, cultural norms, and prevalence of POP in Nepali women, Caagbay et al created an illustrative pamphlet on how to contract pelvic floor muscles as well as provided verbal instruction on pelvic floor muscle activation. Transabdominal real time ultrasound was applied to assess the muscle contraction of 15 women after they received this education. Unfortunately, even after being taught how to engage their pelvic floor muscles, only 4 of 15 correctly contracted their pelvic floors.

This study highlighted that brief verbal instruction plus an illustrative pamphlet was not sufficient in teaching Nepali women how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles. Although there was a small sample size, these results can likely be extrapolated to the larger population. Further research is needed to determine how to effectively teach correct pelvic floor muscle awareness to women with low literacy and/or who reside in resource limited areas. Lastly, it is important to consider the significance of fascial and connective tissue integrity within the pelvic floor when addressing pelvic organ prolapse.

1 Can a leaflet with brief verbal instruction teach Napali women how to correctly contract their pelvic floor muscles? DM Caagbay, K Black, G Dangal, C Rayes-Greenow. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council 15 (2), 105-109.

https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/JNHRC/article/viewFile/18160/14771

2 Pelvic Health Podcast. Lori Forner. Pelvic organ prolapse in Nepali women with Delena Caagbay. May 31, 2018.

3 The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse in a Nepali gynecology clinic. (2017) F. Turel, D. Caagbay, H.P. Dietz. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sydney Medical School Napean, University of Sydney.

4 The prevalence of major birth trauma in Nepali women. (2017) F. Turel, D. Caagbay, H.P. Dietz. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sydney Medical School Nepean, University of Sydney.

In 1984, Mersheed Sinaki MD and Beth Mikkelsen, MD published a landmark article based on their research with osteoporotic women. (Yes, it was 1984 but this is one study no one would want to reproduce).1

The study follows 59 women with a diagnosis of postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis and back pain who were divided into 4 groups that included spinal Extension (E), Flexion (F), Combined (E+F), or No Therapeutic Exercises (N). Ages ranged from 49 to 60 years (mean, 56 years). Follow-up ranged from one to six years (mean for the groups, 1.4 to 2 years). All patients had follow-up spine x-rays before treatment and at follow-up, at which time any further wedging and compression fractures were recorded. Additional fractures occurred as follows:

The study follows 59 women with a diagnosis of postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis and back pain who were divided into 4 groups that included spinal Extension (E), Flexion (F), Combined (E+F), or No Therapeutic Exercises (N). Ages ranged from 49 to 60 years (mean, 56 years). Follow-up ranged from one to six years (mean for the groups, 1.4 to 2 years). All patients had follow-up spine x-rays before treatment and at follow-up, at which time any further wedging and compression fractures were recorded. Additional fractures occurred as follows:

Group E: 16%

Group F: 89%

Group E+F: 53%

Group N: 67%

This study suggests that a significantly higher number of vertebral compression fractures occur in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis who followed a flexion based exercise program, than those using extension exercises. It also indicated that patients who did no exercises were less likely to sustain a vertebral compression fracture than those doing flexion exercises.

Due to the anatomical nature of the thoracic spine, the vertebral bodies are placed into a normal kyphosis. The anterior portion of the thoracic spine carries an excess load which can predispose an individual to fracture. Combine the propensity of flexion based daily activities such as brushing teeth, driving, texting or typing, with the fact that vertebral bodies are primarily made up of trabecular (spongy) bone and you have a recipe for disaster.

In the US, studies suggest that approximately one in two women and one in four men age 50 and older will break a bone due to osteoporosis.2 Now picture the many individuals who think that the only way to strengthen their core is by doing sit ups or crunches, further compressing the anterior portion of the spine. Often these exercises are being taught or led by fitness instructors who unknowingly put their clients at risk. Only 20-30% of compression fractures are symptomatic.3 This means that individuals may continue performing crunches, sit-ups, or toe touches even after they have fractured. No one realizes it until the person may notice a loss in height (they have trouble reaching a formerly accessible shelf or trouble hanging up clothes,) or the fracture is seen on an x-ray for pneumonia, etc. The Dowager’s Hump (hyper-kyphosis) may begin to appear. Or the person sustains another fragility fracture; possibly a hip.

Note that the E Group (Extension) still sustained fractures but significantly less than the other three groups. This suggests that there is a protective effect in strengthening the back extensors which has led to an emphasis on Site Specific back strengthening exercises as well as correct weight bearing activities.

Telling osteoporosis patients that they should exercise without giving them specific guidelines (such as in the Meeks Method) is doing them a disservice. General exercise provides minimal to no benefit in building stronger bones and the wrong exercises could put them at great risk for fractures. Educating our referral sources for the need to recommend therapists trained in correct osteoporosis management and the difference between “right” and “wrong” exercises may be the first step in reducing fragility fractures.

1. Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1984 Oct; 65.

2. NOF.org. National Osteoporosis Foundation

3. McCarthy J, MD, Davis A, MD, Am Family Physician. Diagnosis and Management of Vertebral Compression Fractures

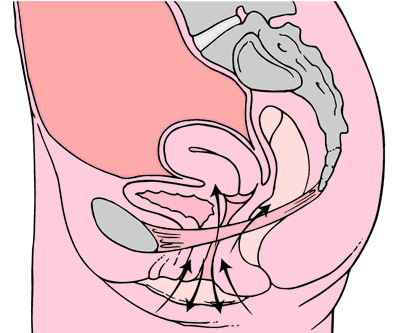

Perineal massage involves pelvic floor muscle stretching by application of an external pressure to muscle and connective tissue in the perineal region. It is performed 4 to 6 weeks before childbirth to help the soft tissue in that region to withstand stretching during labor. This helps to prevent perineum during birth by decreasing the need for an episiotomy or an instrument-assisted delivery. Lengthening of skeletal muscles is known to modify the viscoelastic properties of the muscle-tendon unit, which decreases the tension peak of the musculature and therefore, chances of injury.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Instrument-assisted stretching is performed with the help of an inflatable silicon balloon that can be pumped to gradually stretch the vagina and perineum. However, the evidence to support its benefit is lacking. In fact, there is some concern that pelvic floor muscle stretching may cause a decrease in muscle strength. Some have argued that such exercise neither improve or worsen pelvic function (Labrecque M, et al., Medi-dan, et al.). While a meta-analysis by Aquino, et al. concluded that perineal massage during labor significantly lowered risk of severe perineal trauma, such as third and fourth degree lacerations (Aquino, et al.).

A recent major study done by deFreitas, et al., perineal massage and instrument-assisted stretching were found to improve perineal muscle extensibility when performed in multiple sessions on primiparous women beginning at 34th week of gestation, which is very helpful in preventing child trauma in labor; however, there was no increase in muscle strength.

The technique of performing the manual perineal massage (as exemplified in the aforementioned study) may involve two sessions per week for a month by an OBGYN-focused physiotherapist. The patients are rested in dorsal decubitus position with the inferior limbs semi-flexed and the lower limbs and feet supported on the examination table. Coconut oil can be used for the perineal massage - which starts off with circular movements in the external area of the vulva, around the vagina and in the central tendon of the perineum, followed by the index and middle fingers inserted approximately 4 cm in the vaginal introitus for an internal massage of the lateral walls of the vagina ending toward the anus, repeated four times on each side, with the whole process lasting approximately 10 minutes.

Instrument-assisted procedure may include inserting the instrument (Epi-No) covered with a condom and lubricated with a water-based gel, inflated at the vaginal introitus so that 2 cm of the balloon is visible, making sure the patient can tolerate the stretching, and are advised to keep the pelvic floor relaxed as the instrument is slowly expelled during expiration. Physiotherapist supervision is necessary in order to maintain the correct positioning of the balloon as it lengthens the muscles. He/she will also ensure proper expulsion of the equipment during expiration.

Overall, perineal massage techniques (with or without instrumentation) are beneficial in terms of preventing trauma during labor. There are many studies that support the efficacy of these techniques in doing so (Leon-Larios, et al.). But it is also important to appreciate the limitations and use it judiciously.

Randomized trial of perineal massage during pregnancy: perineal symptoms three months after delivery. Labrecque M, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000.

Perineal massage during pregnancy: a prospective controlled trial. Mei-dan E, et al. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008.

Perineal massage during labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aquino CI, et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018.

Effects of perineal preparation techniques on tissue extensibility and muscle strength: a pilot study. de Freitas SS, et al. Int Urogynecol J. 2018.

Influence of a pelvic floor training programme to prevent perineal trauma: A quasi-randomised controlled trial. Leon-Larios F, et al. Midwifery. 2017.

After completing an intake on a patient and learning that her history of constipation started about 3 years ago with insidious onset, the story wasn’t really making any sense of how or why this started. Yes, she was menopausal. Yes, she seemed to be eating fiber and drinking water. Yes, she got a bowel movement urge daily, but her bowel movements felt incomplete. Yes, she was a little older, using Estrace cream, and her mobility had slowed down, but nothing seemed to make sense in the story that was leading me to believe it was an emptying problem or a stool consistency issue. She had a bowel movement urge, she could empty, but it was incomplete.

So, after explaining about physical therapy, the muscle problems involved and what we do here, it led us to the physical examination portion. I explained that we check both the vaginal and rectal pelvic floor muscle compartments to determine rectal fullness internally, check for a rectocele, check for muscle lengthening (excursion) and shortening (contraction). She was on board and desperate to find an answer. She was eager for me to help her find an answer to her emptying problem that she had for the last 3 years.

So, after explaining about physical therapy, the muscle problems involved and what we do here, it led us to the physical examination portion. I explained that we check both the vaginal and rectal pelvic floor muscle compartments to determine rectal fullness internally, check for a rectocele, check for muscle lengthening (excursion) and shortening (contraction). She was on board and desperate to find an answer. She was eager for me to help her find an answer to her emptying problem that she had for the last 3 years.

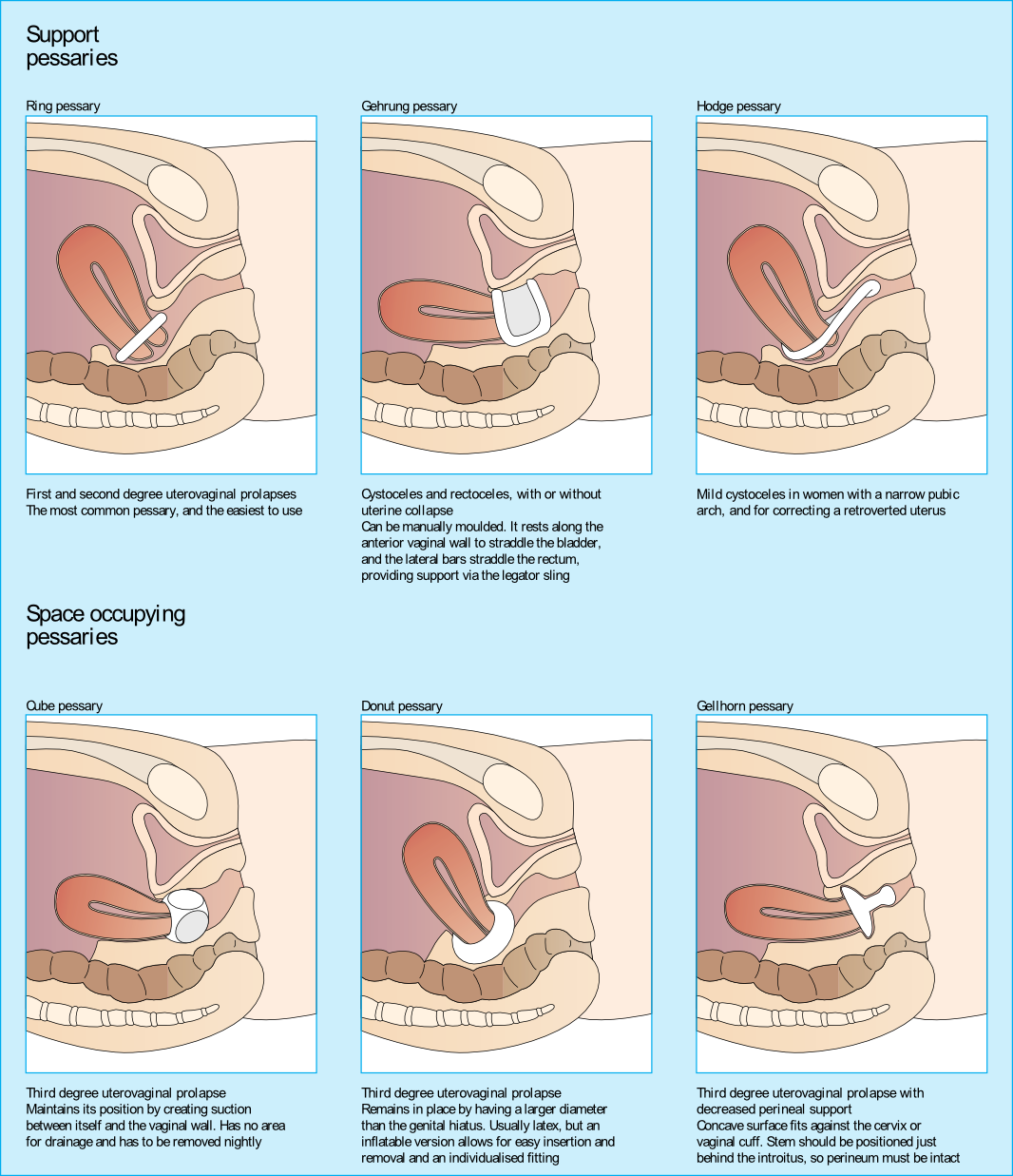

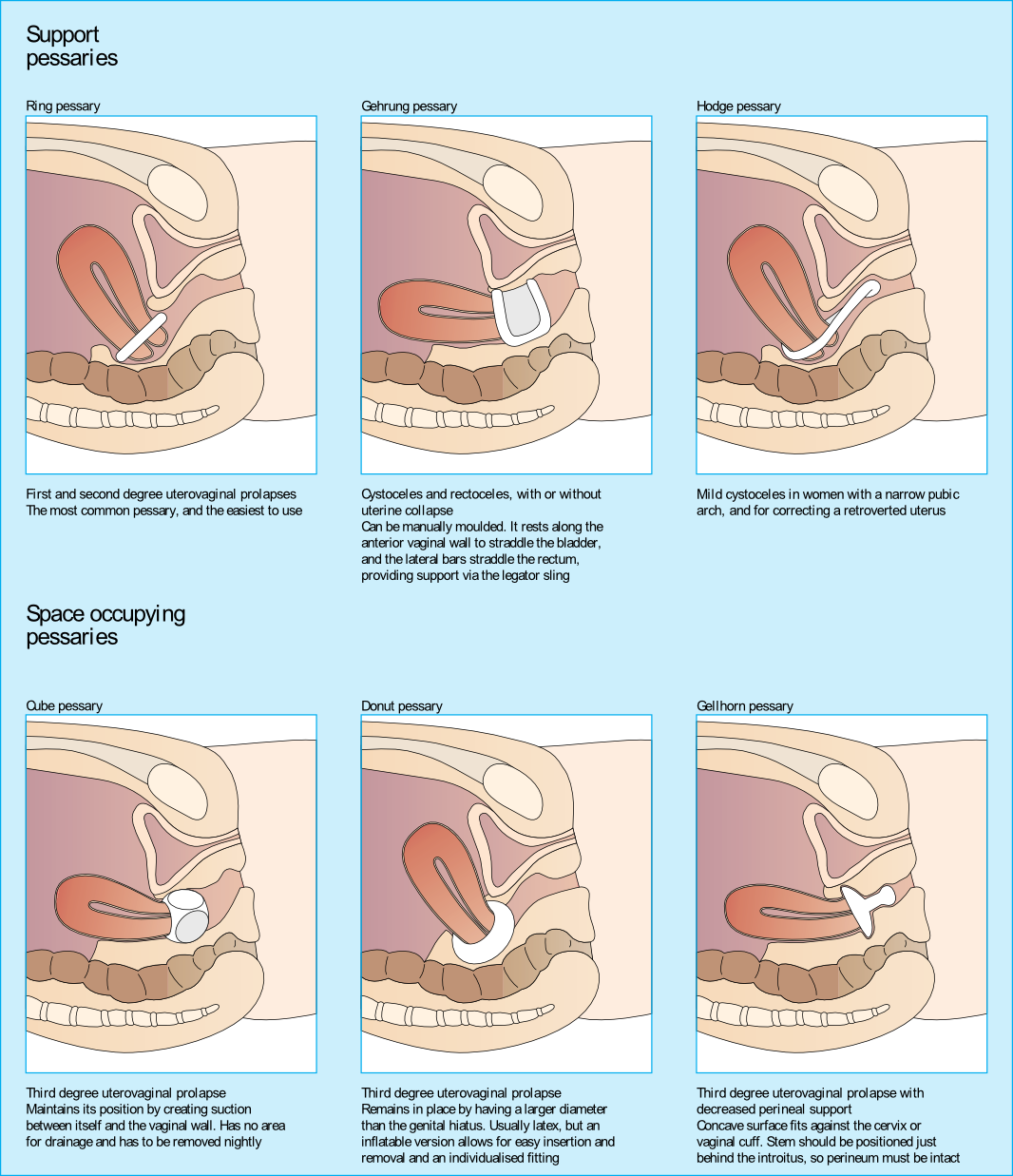

Upon entering her vaginal canal slowly, I start to move around and felt a ring of plastic. “Are you wearing a pessary?” I asked. “Pessary? Oh, yes, I forgot to tell you about that!”, she exclaimed. “How long have you been using it?” I asked. “About 3 years…” she answered.

I sent her back to the urogynecologist to get fit for another type of pessary as her muscle examination proved to be negative. Since that time, I have added the question “Do you wear a pessary?” as part of the constipation intake questions. Pessary use creates the ability for a patient to forgo or to extend their time for a surgical intervention due to pelvic organ prolapse.

Looking at the dynamics of the pessary, it may block bowel movement emptying. The recent study by Dengle, et al, published in the October 2018 in the International Urogynecological Journal confirms this anecdotal, clinical finding. The article, Defecatory Dysfunction and Other Clinical Variables Are Predictors of Pessary Discontinuation, looked at reasons for discontinuation of pessary use from April 2014 to January 2017 and did a retrospective chart review on a selected 1071 women. Incomplete defecation had the largest association with pessary discontinuation.

While there are over 20 sizes of pessaries on the market, patients will discontinue use without having a better conversation with their practitioner. From a PT perspective, when the patient comes in with bowel emptying issues, if no muscle dysfunction is found, it needs to be brought to the provider’s attention. Our role in educating the patient on the options that are available and creating this dialogue can prove to be very helpful in those suffering from pelvic organ prolapse and defecatory dysfunction.

Dengler, EG et al. "Defecatory dysfunction and other clinical variables are predictors of pessary discontinuation." Int Urogynecol J. 2018 Oct 20. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3777-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30343377