As pelvic rehabilitation providers, it may be safe to assume a lot of us are treating adults with bladder and bowel dysfunction. Often we get questions from these patients about treatment for children with voiding dysfunction. How comfortable are we treating children for these problems and what would we do? Pediatric voiding dysfunction and bowel problems are common and can have significant consequences to quality of life for the child and the family, as well as negative health consequences to the lower urinary tract if left untreated. No clear gold standard of treatment for pediatric voiding dysfunction has been established and treatments range from behavioral therapy to medication and surgery.

A randomized controlled trial in 2013 that was published in European Journal of Pediatrics, explores treatment options for pediatric voiding dysfunction. Pediatric voiding dysfunction is defined as involuntary and intermittent contraction or failure to relax the urethral striated sphincter during voluntary voiding. The dysfunctional voiding can present with variable symptoms including urinary urgency, urinary frequency, incontinence, urinary tract infections, and abnormal flow of urine from bladder back up the ureters (vesicoureteral reflux).

A randomized controlled trial in 2013 that was published in European Journal of Pediatrics, explores treatment options for pediatric voiding dysfunction. Pediatric voiding dysfunction is defined as involuntary and intermittent contraction or failure to relax the urethral striated sphincter during voluntary voiding. The dysfunctional voiding can present with variable symptoms including urinary urgency, urinary frequency, incontinence, urinary tract infections, and abnormal flow of urine from bladder back up the ureters (vesicoureteral reflux).

The 2013 study compared 60 children over one year who were diagnosed with dysfunctional voiding into two treatment groups. One group received behavioral urotherapy combined with PFM (pelvic floor muscle) exercises while the other group received just behavioral urotherapy. The behavioral urotherapy consisted of hydration, scheduled voiding, toilet training, and high fiber diet. Voiding pattern, EMG (electromyography) activity during voids, urinary urgency, daytime wetting, and PVR (post-void residue) were assessed at the beginning and end of the one year study with parents completing a voiding and bowel habit chart as well as uroflowmetry with pelvic floor muscle sEMG (surface electromyography) was administered to the child for voiding metrics.

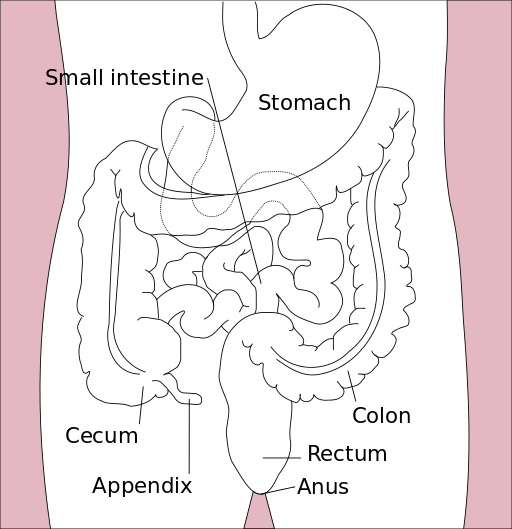

All parents and children in both groups received education about urinary and gastrointestinal tract function as well as healthy bladder habits, effects of high fiber diet, scheduled voiding, and normal mechanics of toilet training. For the group that completed PFM exercises and education, they participated in 12 sessions (2x/week for 30 minutes) to learn the PFM exercises under the guidance of a single physical therapist. There was bimonthly follow up for both groups throughout the 12 months to ensure retention and application of the behavioral urotherapy.

The goal of the PFM exercises for the children was too restore the normal function of the PFM’s and their coordination with abdominal muscles. The exercises that the children completed, included exercises with and without a swiss ball. The exercises without a swiss ball included breathing with the diaphragm, Transversus Abdominus muscle isolation, hip adductor squeeze (isolation), bridging with PFM relaxation, and cat/camel to improve lumbopelvic coordination. Swiss ball exercises included seated PFM contraction and relaxation exercise with a seated lift and relax, supine bridge with roll out on the ball with PFM contraction, and supine swiss ball lift with the legs and pelvic contraction. (Pictures and more details about how the exercises were carried out in the article itself.)

The conclusion of the study was that the functional PFM exercises with swiss ball combined with behavioral urotherapy reduced the frequency of urinary incontinence, PVR (post void residue), and the severity of constipation in children with voiding dysfunction. The children in the combined group showed improvements with voiding pattern, reduced EMG activity during voids, reduced urgency, reduced daytime wetting, and improvements with more complete emptying with voids (reduced PVR).

The Functional PFM exercises are easy to teach and easy for children to complete. They are a safe, inexpensive, and effective treatment option for children with dysfunctional voiding. PFM exercises combined with behavioral urotherapy seems to be a logical treatment option for treating pediatric voiding dysfunction.

To learn more about pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction and treatment for it consider attending Dawn Sandalcidi's Pediatric and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction course. The three opportunities in 2016 are Pediatric Incontinence - Augusta, GA April 16-18, Pediatric Incontinence - Torrance, CA June 11-12, and Pediatric Incontinence - Waterford, CT on September 17-18.

Seyedian, S. S. L., Sharifi-Rad, L., Ebadi, M., & Kajbafzadeh, A. M. (2014). Combined functional pelvic floor muscle exercises with Swiss ball and urotherapy for management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Pediatrics, 173(10), 1347-1353.

As a child, I remember my grandmother rubbing my lower back to help me pass my stubborn stool, a problem which landed me in the hospital twice before I turned 10. Decades later, after the birth of my first baby, I had a grade III perineal tear that made me afraid I would never be able to control my stool from passing. At the time of each situation, I had no idea how many people of all ages experience the two extremes of bowel dysfunction. Thankfully, for patients struggling with either issue, whether it is chronic constipation or fecal incontinence, healthcare practitioners are becoming knowledgeable in how to treat both effectively through classes such as the Herman & Wallace course, “Bowel Pathology, Function, Dysfunction & the Pelvic Floor.”

In 2014, Kelly Scott, MD, authored an article entitled, “Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence.” She reviews the current literature and notes this area of study lacks high quality randomized controlled trials, and further research is needed to provide evidence on the efficacy of different treatment protocols. Up to 24% of the adult population has been shown to experience fecal incontinence. Under the umbrella of pelvic floor rehabilitation lies pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback, rectal balloon catheters for volumetric training, external electrical stimulation, and behavioral bowel retraining. The goals of various biofeedback methods include the following: provide endurance training specifically for the anal sphincter and pelvic floor; improve rectal sensitivity and compliance; and, increase coordination and sensory discrimination of the anal sphincter. Overall, the success rate of pelvic floor rehabilitation for fecal incontinence in most of the studies is 50% to 80%, and it is considered safe as well as effective.

In 2014, Kelly Scott, MD, authored an article entitled, “Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence.” She reviews the current literature and notes this area of study lacks high quality randomized controlled trials, and further research is needed to provide evidence on the efficacy of different treatment protocols. Up to 24% of the adult population has been shown to experience fecal incontinence. Under the umbrella of pelvic floor rehabilitation lies pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback, rectal balloon catheters for volumetric training, external electrical stimulation, and behavioral bowel retraining. The goals of various biofeedback methods include the following: provide endurance training specifically for the anal sphincter and pelvic floor; improve rectal sensitivity and compliance; and, increase coordination and sensory discrimination of the anal sphincter. Overall, the success rate of pelvic floor rehabilitation for fecal incontinence in most of the studies is 50% to 80%, and it is considered safe as well as effective.

On the other end of the spectrum, Vazquez Roque and Bouras (2015) published an article regarding management of chronic constipation. Chronic constipation (CC) in the general population has a prevalence of 20%, and the elderly population has a higher rate than the younger population. Chronic constipation is commonly treated with stool softeners, fiber supplements, laxatives, and secretagogues. However, as in all areas of healthcare, a thorough examination needs to be performed to assess the source of the problem. Determining whether a patient exhibits slow transit constipation or a true pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) via blood work, rectal exam, and appropriate PFD tests is essential to provide the appropriate treatment. When the CC culprit is dysfunction of the pelvic floor, clinical trials have proven the efficacy of pelvic floor rehabilitation and biofeedback, making them optimal treatments.

When research indicates a particular type of rehabilitation is effective for treating a wide scope of issues in an area of the body, learning how and when to implement the techniques is paramount for a well-rounded practitioner. Most of us do not dream of treating chronic constipation or fecal incontinence; but, as we mature in our clinical practice, the spectrum of dysfunctions we discover through diagnostic testing and experience grows. Continuing education in previously unexplored territories can only expand the population to whom we provide relief.

Scott, K. M. (2014). Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence. Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, 27(3), 99–105.

Vazquez Roque, M., & Bouras, E. P. (2015). Epidemiology and management of chronic constipation in elderly patients. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 919–930.

The following post comes to us from Herman & Wallace faculty member Tina Allen, PT, BCB-PMD who teaches many courses with the institute. Tina's new course, Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist, will be debuting this October in San Diego, CA.

As a physical therapist who has been treating pelvic floor dysfunction for 20 years, the patient who still impacts me the most happens to be the second patient I ever treated. The patient was a 22 year old woman who, before she even was referred to me for pelvic pain, had already seen 14 medical providers and experienced 10 procedures including a hysterectomy. She had been told by more than half of her providers that this pain was “in her head”, that “she needed counseling”, and that there was no reason for her pain. With 4 years of clinical experience at the time, I felt discouraged and wondered how I was going to help her. Then I remembered that no one else could look at her muscles and biomechanics like a PT could.

As a physical therapist who has been treating pelvic floor dysfunction for 20 years, the patient who still impacts me the most happens to be the second patient I ever treated. The patient was a 22 year old woman who, before she even was referred to me for pelvic pain, had already seen 14 medical providers and experienced 10 procedures including a hysterectomy. She had been told by more than half of her providers that this pain was “in her head”, that “she needed counseling”, and that there was no reason for her pain. With 4 years of clinical experience at the time, I felt discouraged and wondered how I was going to help her. Then I remembered that no one else could look at her muscles and biomechanics like a PT could.

I started out by educating her about the muscles “down there”, observed how she moved with her daily tasks and then I completed her seemingly first ever muscular evaluation of the perineum. After 6 sessions of down training, muscle reeducation, manual therapy, strengthening of her hip and teaching her how to self mobilize the tissues of the perineum, she reported a pain level of 3/10- the lowest her pain level had been since she was 13 years old! Of course, she asked why it took so long for her to be referred to PT.

While this felt like an extreme story to me at the time, I now know that this is still the reality for many of the clients that we work with as pelvic floor PT’s. This experience set up the aspiration for me to have medical residents in my clinic with me to teach them what PT can do for patients and so that the residents can better evaluate their patients. As pointed out in research in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education, residents in obstetrics and gynecology do not feel adequately prepared to manage the care of women who have chronic pelvic painWitzeman & Kopfman, 2014. Specifically, residents reported negative attitudes towards patients with pelvic pain, and feelings of not having enough time to address their patients’ needs. When asked about how they preferred to learn more about care of patients with pelvic pain, the residents were interested in one-on-one clinical teaching as well as use of diagnostic algorithms. At this point in time I have medical residents with me at least 2 days per month. It’s a start!

So, what does a typical day look like with a 1st year OB/GYN resident in your clinic?

First, I always do my best to let my clients know in advance that a physician will be with me that day. The patient can always decline but most patients are accommodating. I have found that most of our patients want to advocate for themselves and others by having that physician with us in our session to teach them about how PT has helped them.

I spend the first 30 minutes when the resident arrives by bringing out the pelvic floor muscle model and explaining the function of all the muscles and how those muscles impact function. I also describe how this function is impacted by fascia, the muscles of the trunk, biomechanics and mind/body connections. Then we start seeing patients. After I have reviewed the patient’s current status, we begin our session. The patient is asked to give the resident their history and medical history. It’s been wonderful to watch my patients teach the residents and to hear the patients be able to explain their condition including procedures and functional restrictions.

The residents will then be instructed to palpate and learn about restricted tissues, observe how the patient uses their pelvic floor muscles, core, trunk and legs with their daily tasks. The residents have the opportunity to observe how we progress the patient’s self care in therapy.

While the session may start with the resident feeling frustrated that they are not able to be seeing their own patients or preparing for their tests, it usually ends with the resident asking when they can come back to the clinic to learn more about what we do and how we can help patients.

I urge all of us to reach out and invite physicians, PA’s, ARNP’s, midwives, naturopaths and nurses into our clinics to learn. With a little advanced planning we can get patients the help they need as soon as possible.

Witzeman, K. A., & Kopfman, J. E. (2014). Obstetrics-Gynecology Resident Attitudes and Perceptions About Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Targeted Needs Assessment to Aid Curriculum Development. Journal of graduate medical education, 6(1), 39-43.

The following comes to us from Felicia Mohr, DPT, a guest contributor to the Pelvic Rehab Report.

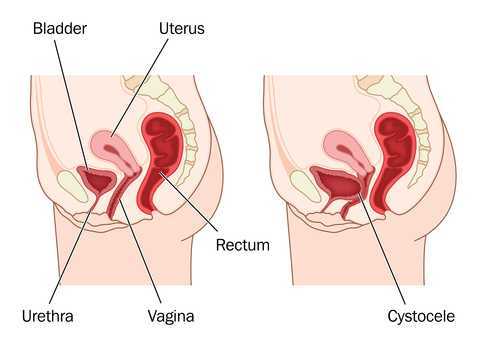

Vaginal mesh kits were used frequently early in the millennium as they led to high initial anatomic success rates with peak use between 2008 and 2010. Objectively they seemed to help elevate women’s pelvic organs to appropriate anatomical locations. Unfortunately there has been a high rate (10% according to a review of current literature on PubMedBarski 2015) of mesh erosion causing recurrent prolapse and/or stress urinary incontinence. Also there are cases when the mesh product perforates surrounding organs causing numerous dangerous complications. The rate of mesh-related complications according to current research is 15-25%. As a result, the FDA has reclassified the risk of synthetic mesh into a higher risk category so that the public has an increased awareness of the risk involved in these types of surgeries.

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2015, reviewed the risk factors for mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (Deng, et al). They concluded the following factors increase risk of mesh erosion: younger age, more childbirths, premenopausal states, diabetes, smoking, concomitant hysterectomy, and surgery performed by a junior surgeon. Moreover, concomitant POP surgery and preservation of the uterus may be the potential protective factors for mesh erosion.

A systematic review and meta-analysis, published in 2015, reviewed the risk factors for mesh erosion following female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery (Deng, et al). They concluded the following factors increase risk of mesh erosion: younger age, more childbirths, premenopausal states, diabetes, smoking, concomitant hysterectomy, and surgery performed by a junior surgeon. Moreover, concomitant POP surgery and preservation of the uterus may be the potential protective factors for mesh erosion.

It is a common practice to perform a hysterectomy with a POP surgery. Reason being that the oversized uterus from childbearing adds extra weight on pelvic organs. However, the latter study as well as two other recent studies published in 2015 (Huang, Farthmann) also provide evidence that there is no benefit to a concomitant hysterectomy at the 2.5 year follow up and can lead to less satisfaction with surgery according to patient surveys respectively.

Keep in mind that all pelvic floor surgeries do not use the same amount of mesh material and different procedures have different risks associated with them. One retrospective study (Cohen, 2015) addressing incidence of mesh extrusion categorized 576 subjects into three categories: pubo-vaginal sling (PVS) (a small string of mesh around the urethra specifically addressing stress urinary incontinence only); PVS and anterior repair (also referred to as cystocele or bladder prolapse); and PVS with anterior and/or posterior repairs (also referred to as rectocele or rectal prolapse). Mesh extrusion for these types of procedures occurred at the follow rates: approximately 6% for PVS subjects, 15% for PVS + anterior repair, and 11% for PVS + anterior and/or posterior repair. This study did not account for any other types of mesh-related complications.

Pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence make up some of the most common conditions for which patients seek Pelvic Floor physical therapy and perhaps this will allow us to better speak to current research on surgical options.

1. Barski D, Deng EY. Management of Mesh Complications after stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolaps repair: review and analysis of the current literature. Biomed Research International; 2015Article ID 831285.

2. Deng T. et al. Risk factor for mesh erosion after female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU International. Doi:10.1111/bju.13158.

3. Huang LY, et al. Medium-term comparison of uterus preservation versus hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse treatment with prolift mesh. International Urogynecology Journal. 2015;26(7):1013-20.

4. Farthmann J, et al. Functional outcome after pelvic floor reconstructive surgery with or without concomitant hysterectomy. Archives of Gynec and Obstet. 2015; 291(3):573-7.

5. Cohen S, Kaveler E. The incidence of mesh extrusion after vaginal incontinence and pelvic floor prolapse surgery. J of Hospital Admin. 2014; 3(4): www.sciedu.ca/jha.

After menopause, more than half of women may have vulvovaginal symptoms that can impact their lifestyle, emotional well-being and sexual health. What's more, the symptoms tend to co-exist with issues such as prolapse, urinary and/or bowel problems. But unfortunately many women aren't getting the help they need, despite a growing body of evidence that skilled pelvic rehab interventions are effective in the management of bladder/bowel dysfunctions, POP, sexual health issues and pelvic pain.

Vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, disrupted sleep, and weight gain have been listed as the top five symptoms experienced by postmenopausal women in North America and Europe, according to a study by Minkin et al 2015, and they also concluded ‘The impact of postmenopausal symptoms on relationships is greater in women from countries where symptoms are more prevalent.’

Vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, disrupted sleep, and weight gain have been listed as the top five symptoms experienced by postmenopausal women in North America and Europe, according to a study by Minkin et al 2015, and they also concluded ‘The impact of postmenopausal symptoms on relationships is greater in women from countries where symptoms are more prevalent.’

Between 17% and 45% of postmenopausal women say they find sex painful, a condition referred to medically as dyspareunia. Vaginal thinning and dryness are the most common cause of dyspareunia in women over age 50. However pain during sex can also result from vulvodynia (chronic pain in the vulva, or external genitals) and a number of other causes not specifically associated with menopause or aging, particularly orthopaedic dysfunction, which the pelvic physical therapist is in an ideal position to screen for.

According to the North America Menopause Society, ‘…beyond the immediate effects of the pain itself, pain during sex (or simply fear or anticipation of pain during sex) can trigger performance anxiety or future arousal problems in some women. Worry over whether pain will come back can diminish lubrication or cause involuntary—and painful—tightening of the vaginal muscles, called vaginismus. The result can be a vicious circle, again highlighting how intertwined sexual problems can become.’

The research has demonstrated that the optimal strategy for post-menopausal stress incontinence is a combination of local hormonal treatment and pelvic floor muscle training – the strategy of combining the two approaches has been shown to be superior to either approach used individually (Castellani et al 2015, Capobianco et al 2012) and similar conclusions can be drawn for promoting sexual health peri- and post-menopausally.

The pelvic rehab specialist may be called upon to screen for orthopaedic dysfunction in the spine, hips or pelvis, to discuss sexual ergonomics such as positioning or the use of lubricant as well as providing information and education about sexual health before, during and after menopause.

To learn more about sexual health and pelvic floor function/dysfunction at menopause, join me in Atlanta in March for Menopause: A Rehab Approach!

Prevalence of postmenopausal symptoms in North America and Europe, Minkin, Mary Jane MD, NCMP1; Reiter, Suzanne RNC, NP, MM, MSN2; Maamari, Ricardo MD, NCMP3, Menopause:November 2015 - Volume 22 - Issue 11 - p 1231–1238

Low-Dose Intravaginal Estriol and Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in Post-Menopausal Stress Urinary Incontinence, Castellani D. · Saldutto P. · Galica V. · Pace G. · Biferi D. · Paradiso Galatioto G. · Vicentini C., Urol Int 2015;95:417-421

Unfortunately one of the most common things we hear in pelvic rehab is “I hope you can help me, you’re my last hope.” In severe cases, this translates to the patient having little hope of surviving their life with pelvic pain. In severe but not necessarily life-threatening cases, being a patient’s last hope can also mean “please help me have sex in my relationship or my partner is going to leave me.” This situation places a lot of pressure on the patient and also on the therapist. How long did it take this patient to find her way to pelvic rehab? Research tells us that most women have been through multiple physicians, under- or misdiagnosed, and that many have failed attempts at intervention with medications or procedures.

It’s clear to women that they are being judged when they go to medical appointments complaining of pelvic pain or pain with intercourse. Although it seems really old school to hear that a provider said “It’s all in your head.” or “How much do you like your partner?” or “Well, you’re getting older, sex isn’t that important.” these dismissive phrases are still used. A study by Nguyen et al., 2013 reported that women who reported chronic pain were more likely to perceive being stereotyped by doctors and others. Interestingly, among the group of women who had chronic vulvar pain, the women who sought care for their condition reported feeling more stigmatized. Because the support a woman perceives may influence her willingness to seek out help for chronic vulvar pain, we need to keep educating our peers, the public, and the providers about the real challenges women face, and the power of rehabilitation in overcoming those challenges.

It’s clear to women that they are being judged when they go to medical appointments complaining of pelvic pain or pain with intercourse. Although it seems really old school to hear that a provider said “It’s all in your head.” or “How much do you like your partner?” or “Well, you’re getting older, sex isn’t that important.” these dismissive phrases are still used. A study by Nguyen et al., 2013 reported that women who reported chronic pain were more likely to perceive being stereotyped by doctors and others. Interestingly, among the group of women who had chronic vulvar pain, the women who sought care for their condition reported feeling more stigmatized. Because the support a woman perceives may influence her willingness to seek out help for chronic vulvar pain, we need to keep educating our peers, the public, and the providers about the real challenges women face, and the power of rehabilitation in overcoming those challenges.

Vulvodynia is a common pelvic pain condition, and one that typically is associated with painful intercourse, or dyspareunia. (Arnold et al., 2006) It's estimated that by the age of 40, as many as 8% of women will have or have had a diagnosis of vulvodynia (Harlow et al., 2014), and this is clearly a significant quality of life issue.

Physical therapy has been shown to be successful in treating vulvar pain and pain with intercourse, including as part of a multidisciplinary approach. (Brotto et al., 2015) That's why Herman & Wallace is so eager to help empower more therapists to help patients live a life free of vulvar pain and dyspareunia. You can learn more about our courses and other resources at https://www.hermanwallace.com/continuing-education-courses.

Arnold, L. D., Bachmann, G. A., Kelly, S., Rosen, R., & Rhoads, G. G. (2006). Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with co-morbidities and quality of life. Obstetrics and gynecology, 107(3), 617.

Brotto, L. A., Yong, P., Smith, K. B., & Sadownik, L. A. (2015). Impact of a multidisciplinary vulvodynia program on sexual functioning and dyspareunia. The journal of sexual medicine, 12(1), 238-247.

Harlow, B. L., Kunitz, C. G., Nguyen, R. H., Rydell, S. A., Turner, R. M., & MacLehose, R. F. (2014). Prevalence of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of vulvodynia: population-based estimates from 2 geographic regions. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 210(1), 40-e1.

Nguyen, R. H., Turner, R. M., Rydell, S. A., MacLehose, R. F., & Harlow, B. L. (2013). Perceived stereotyping and seeking care for chronic vulvar pain. Pain Medicine, 14(10), 1461-1467.

The following post comes to us from long-time faculty member Dawn Sandalcidi PT, RCMT, BCB-PMD! Dawn is a figurehead in the world of pediatric pelvic floor, she teaches Pediatric Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (available three times in 2016) and she just completed the 2nd edition of the Pediatric Pelvic Floor Manual!! Today Dawn is sharing her insights an urotherapy for pediatric patients.

If you read any papers on pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction you will often come across the word "urotherapy". It is by definition a conservative based management based program used to treat lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction using a variety of health care professionals including the physician, Physical Therapists, Occupational Therapists and Registered Nurses.

If you read any papers on pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction you will often come across the word "urotherapy". It is by definition a conservative based management based program used to treat lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction using a variety of health care professionals including the physician, Physical Therapists, Occupational Therapists and Registered Nurses.

Basic urotherapy includes education on the anatomy and function of the LUT, behavior modifications including fluid intake, timed or scheduled voids, toilet postures and avoidance of holding maneuvers, diet, bladder irritants and constipation. This needs to be tailored to the patients’ needs. For example a child with an underactive bladder needs to learn how to sense urge and listen to their body and a child who postpones a void needs to be on a voiding schedule. Urotherapy alone can be helpful however a recent study demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in uroflow, pelvic floor muscle electromyography activity during a void, urinary urgency, daytime wetting and reduced post void residual (PVR) in those patients who received pelvic floor muscle training as compared to Urotherapy alone. This is great news for all of us who are qualified to teach pelvic floor muscle exercise!

The International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) has now expanded the definition of Urotherapy to include Specific Urotherapy. This includes biofeedback of the pelvic floor muscles by a trained therapist who is able to teach the child how to alter pelvic floor muscle activity specifically to void. It also includes neuromodulation for many types of lower urinary tract dysfunction but most commonly with overactive bladder and neurogenic bladder. Cognitive behavioral therapy and psychotherapy are always important to assess (see blog post on psychological effects of bowel and bladder dysfunction).

It truly does take a village to help this kiddos and I am honored to be a team player!

To learn more about pediatric incontinence and pelvic floor rehabilitation, join Dawn Sandalcidi at one of her courses this year! Details at the following links:

Pediatric Incontinence - Augusta, GA - Apr 16, 2016 - Apr 17, 2016

Pediatric Incontinence - Torrance, CA - Jun 11, 2016 - Jun 12, 2016

Pediatric Incontinence - Waterford, CT - Sep 17, 2016 - Sep 18, 2016

Chang SJ, Laecke EV, Bauer, SB, von Gontard A, Bagli,D, Bower WF,Renson C, Kawauchi A, Yang SS-D. Treatment of daytime urinary incontinence: a standardization document from the international children's continence society. Neurourol Urodyn 2015;Oct 16. doi:10.1002/nau.22911

Ladi Seyedian SS, Sharifi-Rad L, Ebadi M, Kajbafzadeh AM. Combined functional pelvic floor muscle exercise with swiss ball and Urotherapy for management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr.2014 Oct;173(10):1347-53. I.J.N. Koppen, A. von Gontard, J. Chase, C.S. Cooper, C.S. Rittig, S.B. Bauer, Y. Homsy, S.S. Yang, M.A. Benninga. Management of functional nonretentive fecal incontinence in children: recommendations from the International Children’s Continence Society. J of Ped Urol (2015)

Koppen IJ, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Dinning PG, Yacob D, Levitt MA, Benninga MA. .Childhood constipation: finally something is moving! Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Oct 14:1-15.

Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute faculty member, Ginger Garner PT, L/ATC, PYT, will be giving 2 lectures at this year’s annual Montreal International Symposium for Therapeutic Yoga, or MISTY for short, in Montreal, Quebec. The first is a 2-hour lecture titled, Vocal Liberation, and the second is a 4-hour lecture titled, Hip Preservation: Yoga Reconsidered, Visit http://www.homyogaevents.com to learn more. Read below as Ginger shares why the voice is a linking science.

The Voice as a Linking Science for Clinical and Business Efficacy

Your voice can be the key to your success. Forbes magazine’s #3 habit in an article, Five Habits of Highly Effective Communicators, is “Find your own voice.” London’s think tank Tomorrow’s Company declares in a recent report on efficacy in business leadership, “Having a voice really matters for employees today.” The director of the Involvement and Participation Association (IPA) and vice-chair of the London-based MadLeod Review on employee engagement says, “Voice is extremely important because there are many changing business concepts and one of the essential ones is trust. Our voice is one of the things we really need to change old management paradigms and build trust in an organization.”

Your voice can be the key to your success. Forbes magazine’s #3 habit in an article, Five Habits of Highly Effective Communicators, is “Find your own voice.” London’s think tank Tomorrow’s Company declares in a recent report on efficacy in business leadership, “Having a voice really matters for employees today.” The director of the Involvement and Participation Association (IPA) and vice-chair of the London-based MadLeod Review on employee engagement says, “Voice is extremely important because there are many changing business concepts and one of the essential ones is trust. Our voice is one of the things we really need to change old management paradigms and build trust in an organization.”

If you are an instructor, teacher, educator, therapist, or all four, having a voice is synonymous with having a job. You can’t do your job without a voice. And yet, we don’t spend much time thinking about vocal physiology, much less how to maintain and even improve it.

The most powerful change agent or therapeutic modality you have - is your voice. Yet, the voice is often overlooked as a therapeutic tool. Think of how important it is for someone giving a TED talk to have good vocal quality, for example. Now consider how important it is for others, like you, who may have to speak for hours on end each day. The vocal folds must be cared for just like we attend to the mind and body during postural yoga practice or movement therapy.

What were the other findings of the report?

- Voice is the foundation of sustainable business success. It increases employee engagement, enables effective decision-making and drives innovation.

- Finding your voice involves both cultural and structural pursuit. First, we need to be culturally competent and sensitive. Only then can we provide the right process through which our voice can be heard.

The power of the voice cannot be ignored, particularly for those who have allergies, respiratory issues, or struggle to make a powerful impact or to establish themselves as an effective team member or thought leader. Oftentimes, the voice is the single variable that holds us back from making the success we are seeking in our work. US News World and Report states,

“Whether you are an aspiring leader or in a support role, developing your communication skills can impact your success. First, let’s take a look at the complexities of communication. It's more than the words you use. It's how and when you choose to share information. It's your body language and the tone and quality of your voice.”

Psychology Today and National Public Radio have recently reported on the relationship between vocal quality and job success and effectiveness. Both agree that speech rate, tone of voice, facial expression, and diction have a great deal of power to make or break effective communication. If tone doesn’t match facial expression, for example, neural dissonance occurs, which erodes trust, increase skepticism, and cooperation.1 In fact, warm vocal tone is a sign of transformational leadership, which generates “more satisfaction, commitment, and cooperation between team members”.2 Changing pitch increases therapeutic potential and improves the chances of your being understood by colleagues, especially when diction is congruent with emotion.1 Additionally, training mindfulness during public speaking can improve prefrontal cortex activity, which allows for improved social awareness, mood-regulation, decision-making, and empathy.4 Vocal awareness and training can slow your pace of speaking, which is shown to deepen others’ respect for you and simultaneously calm anxiety, traits which are bridge-building and healing for all relationships, business and personal.

About MISTY

MISTY is a not-for-profit organization and event dedicated to teaching others about therapeutic yoga.

Ginger’s workshop, “Vocal Liberation,” will introduce techniques for developing and preserving the voice, including projection, quality, longevity, and therapeutic impact through fusion of nada yoga and ENT physiology, which Ginger has developed over her career in public speaking and vocal performance. Want to learn about therapeutic yoga at MISTY? There’s still time to join Ginger and a host of other talented speakers and therapists. Learn more and register at http://www.homyogaevents.com.

Use of affective prosody by young and older adults. Dupuis K, Pichora-Fuller MK. Psychol Aging. 2010 Mar;25(1):16-29.

Leadership = Communication? The Relations of Leaders' Communication Styles with Leadership Styles, Knowledge Sharing and Leadership Outcomes. de Vries RE, Bakker-Pieper A, Oostenveld W. J Bus Psychol. 2010 Sep;25(3):367-380.

Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Tang YY, Ma Y, Wang J, Fan Y, Feng S, Lu Q, Yu Q, Sui D, Rothbart MK, Fan M, Posner MI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Oct 23;104(43):17152-6.

Since the passing of Title IX in 1972, which protects people from sex discrimination in education or activity programs receiving federal funding, the number of females participating in sports has greatly increased. The National Federation of State High School Associations states that in 2011 nearly 3.2 million girls are participating in high school sports.

Unfortunately, a consequence of this increased participation in sports is a higher prevalence in urinary incontinence (UI) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in female athletes. Borin et al looked at the ability of nulliparous female athletes to generate intracavity perineal pressure in comparison to nonathletic women. The study demonstrated that higher mean pressures were generated by nonathletic women in comparison to the athletic women group and that lower perineal pressures in the athletic women were also related to number of games per year and time spent on sport specific workouts and strength training workouts.

UI and SUI are underreported in the general population and also in the athletic population. As health care professionals it is important to screen for UI and SUI in our clients. Physical therapy interventions using pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation have shown to decrease the severity of UI and SUI (Rivalta et al, Hulme). Rivalta used internal methods to improve the function of the pelvic floor muscle. Hulme’s success was achieved through activation of the pelvic floor muscles’ extrinsic synergists.

|

|

Pilates is often used in physical therapy as a therapeutic tool to improve lumbar stability with studies showing increases in abdominal strength (Sekendiz), trunk extensor endurance (Sekendiz) and to improve posture (Kloubec). Pilates is often also used in pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation and can easily be modified for low level clients. For example the use of resistance can assist supporting the weight of the leg. Practical proof, while lying supine in neutral lumbar spine position, stretch an arm and a leg away from center, notice the difficulty to maintain neutral spine. Now hold a resistance strap, which is also attached to the foot, and notice how maintaining neutral lumbar spine is easier to maintain (pictured above).

Pilates can also be modified for the higher level client or more athletic client. The use of arc barrels, BOSUs or the Hooked on Pilates MINIMAX (pictured belowy) allow the athletic client to achieve an inverted position, unloading the pelvic floor muscles. In the inverted position, pelvic floor muscles may be activated as intrinsic and/or extrinsic synergists of the pelvic floor muscles are also activated. These types of exercises may be more appealing to the athletic client ensuring continuation of the exercise post discharge from physical therapy.

|

|

Borin LC, Nunes FR, Guirro EC. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle pressure in female athletes. PMR. 2013; 5(3):189-193.

Hulme, Janet. Beyond Kegels 3rd edition, 2012 Phoenix Publishing Co. Missoula, Montana

Kloubec JA. Pilates for improvement of muscle endurance, flexibility, balance and posture. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:661-667.

Rivalta M, Sughunolfi MC, Micali S, De Stafani S, Torcasio F, Bianchi G, Urinary incontinence and sport. First and preliminary experience with a combined pelvic floor rehabilitation program in three female athletes. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(5);330-334.

Sekendiz B, Altun O, Korkusuv F, Akin S, Effects of pilates exercise on trunk strength, endurance and flexibility in sedentary adult females. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2005;9:52-57.

One of the dilemmas for many clinicians new to pelvic rehab is trying to figure out which equipment to purchase, and how to convince their employer (or themselves) to purchase the equipment. A common question in relation to equipment for pelvic rehabilitation is “what do I really need?” In a perfect world, and based on both existing and emerging research as well as clinical practice recommendations, we would all have access to pressure biofeedback and real-time ultrasound to help us document and train our patients in best strategies. The truth, however, lies in the fact that when those devices are not available, clinical practice can gain meaningful information from our best tools: our eyes and our hands. Certainly when completing research about pelvic floor generated pressures we might choose pressure biofeedback, and when looking for muscle activation patterns, needle EMG is the right choice, but no one should deny patients the opportunity to learn how to increase or decrease muscle activity, focus on movement retraining, and learn strategies to decrease improve quality of life and function because the latest technology is unavailable.

Recent research published in the Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy helps affirm the value of vaginal palpation in an article that assessed the relationship between vaginal palpation, vaginal squeeze pressure, electromyography and ultrasound. Eighty women between the ages of 18 and 35 years old, who had never given birth, and who had no known pelvic floor dysfunction were given a thorough evaluation using a multitude of evaluative methods. These methods included vaginal digital palpation (using Modified Oxford scale), vaginal squeeze pressure, electromyographic activity, diameter of the bulbocavernosus muscles as well as bladder neck movement using transperineal ultrasound. The muscles were assessed in a supine, hooklying position. A strong and positive correlation was found between pelvic floor muscle function and pelvic floor muscle contraction pressure. A less strong correlation was found between pelvic muscle function and pressure and electromyography and ultrasound.

Recent research published in the Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy helps affirm the value of vaginal palpation in an article that assessed the relationship between vaginal palpation, vaginal squeeze pressure, electromyography and ultrasound. Eighty women between the ages of 18 and 35 years old, who had never given birth, and who had no known pelvic floor dysfunction were given a thorough evaluation using a multitude of evaluative methods. These methods included vaginal digital palpation (using Modified Oxford scale), vaginal squeeze pressure, electromyographic activity, diameter of the bulbocavernosus muscles as well as bladder neck movement using transperineal ultrasound. The muscles were assessed in a supine, hooklying position. A strong and positive correlation was found between pelvic floor muscle function and pelvic floor muscle contraction pressure. A less strong correlation was found between pelvic muscle function and pressure and electromyography and ultrasound.

Vaginal pelvic muscle assessment via palpation has been shown to be more accurate when assessed by more experienced therapists, and use of multiple methods may be most valuable in gaining the most accurate data. In addition to validating the usefulness of pelvic muscle palpation as an evaluative tool, the authors point out that transperineal ultrasound may also be the most appropriate tool for pediatric patients or patients who are otherwise not appropriate for internal pelvic muscle assessment.

Pereira, V. S., Hirakawa, H. S., Oliveira, A. B., & Driusso, P. (2014). Relationship among vaginal palpation, vaginal squeeze pressure, electromyographic and ultrasonographic variables of female pelvic floor muscles. Brazilian journal of physical therapy, 18(5), 428-434.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./