Food, at its basic level, provides us with nutrition and sustenance to perform our daily activities. Populations in tune with nature’s cycles of food tend to eat what is available locally based on climate and growth seasons. When societies move beyond simply eating food for energy, but also for flavor, pleasure, and even status, the face of nutrition changes. Whereas some diseases come from a lack of nutrition, many diseases we are faced with in the United States also come from an overabundance of food, with too many calories or too much sugar making up common causes of lack of health. The knowledge within the field of disordered eating is vast, and patients struggling with disordered eating may be fortunate enough to work with a specialist to help recover healthier habits. Even without a diagnosis of disordered eating, many us can identify with unhealthy eating habits, often guided by stress, fatigue, or emotions.

Prior research has studied how we access willpower under different conditions of cognitive stress. In part of this research, participants were given a number to recall (either 2 digits or 7 digits) and then while walking to another location were offered a snack of either fruit salad or chocolate cake. The authors found that the participants who had to recall a 7 digit number more often chose the chocolate cake, leading the researchers to theorize about the role of higher-level processing and making choices. (Shiv et al., 1999) While we may be aware of a tendency to overeat (or make poorer food choices) during times of stress, fatigue, or emotional distress, changing the habits can be very challenging.

Prior research has studied how we access willpower under different conditions of cognitive stress. In part of this research, participants were given a number to recall (either 2 digits or 7 digits) and then while walking to another location were offered a snack of either fruit salad or chocolate cake. The authors found that the participants who had to recall a 7 digit number more often chose the chocolate cake, leading the researchers to theorize about the role of higher-level processing and making choices. (Shiv et al., 1999) While we may be aware of a tendency to overeat (or make poorer food choices) during times of stress, fatigue, or emotional distress, changing the habits can be very challenging.

Resources that discuss improving our eating choices in the face of “emotional eating” offers many alternatives, or ways to soothe ourselves without eating. In her books about this topic, clinical psychologist Susan Albers offers advice that may be helpful for our own habit building and for offering basic advice for our patients who struggle with the issue. (While offering advice to patients about healthy eating and habits is within our scope of practice, if a patient has need for a referral to a counselor, psychologist, or nutritionist, we can coordinate such a referral with the patient’s primary care provider.) In her book titled “50 More Ways to Soothe Yourself Without Food: Mindfulness Strategies to Cope with Stress and End Emotional Eating”, Dr. Albers offers many strategies for altering our habits. Some of these ideas include using acupressure points, breathing, rituals, self-massage, yoga, writing, dancing, art, tea, or sex to defer ourselves from poor eating habits. While eating can be enjoyable and pleasurable, when our patients are struggling with over-eating or eating foods that don’t support nutritional or healing goals, having a discussion about these issues may be useful.

If you are interested in learning more about nutrition, consider joining your pelvic rehab colleagues at one of the two Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist courses this year! Your first chance to attend will be in Kansas City on March 5-6, and later on in Lodi, CA June 25-26.

Albers, S. (2015). 50 More Ways to Soothe Yourself Without Food: Mindfulness Strategies to Cope with Stress and End Emotional Eating. New Harbinger Publications.

Shiv, B., & Fedorikhin, A. (1999). Heart and mind in conflict: The interplay of affect and cognition in consumer decision making. Journal of consumer Research, 26(3), 278-292.

This week we end with a fantastic interview with our featured pelvic rehab practitioner. Nancy Suarez, MS, PT, BCB-PMD, PRPC just joined the ranks of the elite Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioners! Check out our interview below:

Describe your clinical practice:

Describe your clinical practice:

I work in a private practice specializing in women’s and men’s pelvic floor disorders including bowel and bladder issues, prolapse and sexual dysfunction, prenatal and postpartum rehabilitation, pre and postprostatectomy care, and lumbopelvic pain.

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

As a physical therapist who regularly took continuing education courses following PT school, I happened to be looking for a course that might give me more knowledge to help some of my geriatric patients improve their urinary incontinence. I took my first Pelvic Floor course given by Hollis Herman and Kathe Wallace in 2000, and immediately began to make a difference in many of my patient’s lives.

What/who inspired you to become involved in pelvic rehabilitation?

Really it was my patients that inspired me to become involved in pelvic floor rehabilitation; I knew embarassingly little about it on my own until my first course! I was very fortunate to have been given the opportunity to join a pelvic floor specialty practice a few years after that first course, and there I honed my skills and began adding more pelvic floor courses to improve my practice.

What patient population do you find most rewarding in treating and why?

It is honestly difficult for me to choose one type of patient that I find MOST rewarding; it is such a privilege to see patients getting better when they may have thought there was no hope. I do find that I love helping middle aged and older women learn about their pelvic floor and learn how to overcome their incontinence, prolapse and pain.

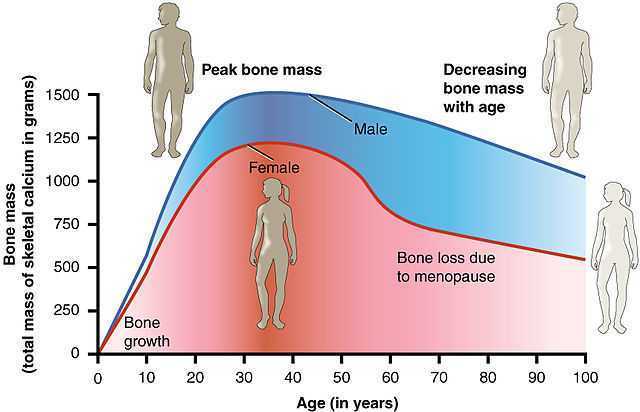

After menopause, more than half of women may have vulvovaginal symptoms that can impact their lifestyle, emotional well being and sexual health. What's more, the symptoms tend to co-exist with issues such as prolapse, urinary and/or bowel problems. But unfortunately many women aren't getting the help they need, despite a growing body of evidence that skilled pelvic rehab interventions are effective in the management of bladder/bowel dysfunctions, POP, sexual health issues and pelvic pain.

Vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, disrupted sleep, and weight gain have been listed as the top five symptoms experienced by postmenopausal women in North America and Europe, according to a study by Minkin et al 2015, and they also concluded ‘The impact of postmenopausal symptoms on relationships is greater in women from countries where symptoms are more prevalent.’ Between 17% and 45% of postmenopausal women say they find sex painful, a condition referred to medically as dyspareunia. Vaginal thinning and dryness are the most common cause of dyspareunia in women over age 50. However pain during sex can also result from vulvodynia (chronic pain in the vulva, or external genitals) and a number of other causes not specifically associated with menopause or aging, particularly orthopaedic dysfunction, which the pelvic physical therapist is in an ideal position to screen for.

Vaginal dryness, hot flashes, night sweats, disrupted sleep, and weight gain have been listed as the top five symptoms experienced by postmenopausal women in North America and Europe, according to a study by Minkin et al 2015, and they also concluded ‘The impact of postmenopausal symptoms on relationships is greater in women from countries where symptoms are more prevalent.’ Between 17% and 45% of postmenopausal women say they find sex painful, a condition referred to medically as dyspareunia. Vaginal thinning and dryness are the most common cause of dyspareunia in women over age 50. However pain during sex can also result from vulvodynia (chronic pain in the vulva, or external genitals) and a number of other causes not specifically associated with menopause or aging, particularly orthopaedic dysfunction, which the pelvic physical therapist is in an ideal position to screen for.

According to the North America Menopause Society, ‘…beyond the immediate effects of the pain itself, pain during sex (or simply fear or anticipation of pain during sex) can trigger performance anxiety or future arousal problems in some women. Worry over whether pain will come back can diminish lubrication or cause involuntary—and painful—tightening of the vaginal muscles, called vaginismus. The result can be a vicious circle, again highlighting how intertwined sexual problems can become.’

The research has demonstrated that the optimal strategy for post-menopausal stress incontinence is a combination of local hormonal treatment and pelvic floor muscle training – the strategy of combining the two approaches has been shown to be superior to either approach used individually (Castellani et al 2015, Capobianco et al 2012) and similar conclusions can be drawn for promoting sexual health peri- and post-menopausally.

The pelvic rehab specialist may be called upon to screen for orthopaedic dysfunction in the spine, hips or pelvis, to discuss sexual ergonomics such as positioning or the use of lubricant as well as providing information and education about sexual health before, during and after menopause.

To learn more about sexual health and pelvic floor function/dysfunction at menopause, join me in Atlanta in March for Menopause: A Rehab Approach.

Prevalence of postmenopausal symptoms in North America and Europe, Minkin, Mary Jane MD, NCMP1; Reiter, Suzanne RNC, NP, MM, MSN2; Maamari, Ricardo MD, NCMP3, Menopause:November 2015 - Volume 22 - Issue 11 - p 1231–1238

Low-Dose Intravaginal Estriol and Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation in Post-Menopausal Stress Urinary Incontinence, Castellani D. · Saldutto P. · Galica V. · Pace G. · Biferi D. · Paradiso Galatioto G. · Vicentini C., Urol Int 2015;95:417-421

Occasionally, as pelvic rehab providers, we will encounter the question from our patients, “Do vaginal weights help with urinary incontinence and pelvic floor performance?” The premise behind the use of vaginal cones or balls is that holding them actively in your vagina with your pelvic floor muscles helps to increase the performance (strength and endurance) of the pelvic floor muscles, assisting in reduction of urinary incontinence.

Of the searched studies, all were randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials. The primary outcomes of the searched studies were pelvic floor muscle performance (strength or endurance) and/or urinary incontinence, both assessed with a valid or reliable method. 37 potentially useful articles were reviewed out of 1324 based on the search criteria, but only one article met all of the inclusion criteria and was included in this review with 192 relevant participants (Wilson and Herbison).

In the included study, the group that used vaginal cones (compared to control group) showed a statistically significant lower rate of urinary incontinence. However, when compared to the pelvic exercises group, the continence rates were similar at 12 months post-partum between the cone group and the exercising group. At 24-44 months post-partum, continence rates amongst all groups were similar, but follow-up rates were very low.

As pelvic rehabilitation providers, it is our job to promote pelvic health and assist our post-partum patients with their pelvic impairments, providing them with options to meet their goals. This review does not make a scientific statement of a preferred mode of pelvic exercise, however, it gives us one more option to consider when teaching patients about how to improve pelvic muscle performance to increase urinary continence following child birth. Pelvic exercise enhances pelvic performance, so if your patient would prefer to use vaginal cones or balls to do their pelvic exercise versus completing pelvic exercises without them, do what works best for the patient. One can argue that any pelvic exercise is better than none in improving performance. The use of vaginal cones or balls may be helpful for urinary continence in post-partum women, and provides us with one tool more when promoting pelvic health in our patients.

Oblasser, C., Christie, J., & McCourt, C. (2015). Vaginal cones or balls to improve pelvic floor muscle performance and urinary continence in women post-partum: A quantitative systematic review. Midwifery, 31(11), 1017-1025.

Wilson, P. D., & Herbison, G. P. (1998). A randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle exercises to treat postnatal urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal, 9(5), 257-264.

Reports in the media of research on mindfulness keep reminding us that mindfulness has positive effects on a wide variety of conditions. In the world of pelvic rehabilitation, which is broad when we consider the scope of the patient populations and diagnoses that we treat, we can find benefits from mindfulness to include bladder dysfunction, pain, and even bowel dysfunction. When specifically addressing bowel dysfunction, there are many studies that promote the benefits of mindfulness on bowel health, including the following research findings for the following topics:

Colitis

In 53 patients diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC), some were randomized into a control group or a treatment arm that consisted of instruction in mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). While mindfulness-based stress reduction did not, in this study, affect the flare-ups of patients with moderately severe ulcerative colitis, the MBSR “…had a significant positive impact on the quality of life…” when compared to patients in the control group. So even though the use of mindfulness did not appear to affect the disease, the patients utilizing mindfulness perceived a higher quality of life even during a flare of their colitis. (Jedel et al., 2014)

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

In another study, 36 people (24 diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and 12 healthy subjects in control group) were studied. The patients who had IBS were divided into equal groups and were treated with either CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) or MBT (mindfulness-based treatment.) The authors conclude that mindfulness-based therapy “…is an effective method to decrease symptoms of patients with IBS…” and that it was more effective than CBT at the 2 month follow-up. (Zomorodi et al., 2014)

Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD)

In reference to the importance of addressing mind, body and spirit for patients who have inflammatory bowel disease, this article discusses the benefits of addressing the psychosocial impacts of gastrointestinal disorders, as the disorders are “…best understood by a combination of genetic, physical, physiological, and psychological factors.” (Jedel et al., 2012)

Functional Gastrointestinal (GI) Disorders

Although a recent analysis of studies on gastrointestinal disorders calls for improvement in methodological quality of the research, the article concludes that “…mindfulness-based interventions may be useful in improving FGID [functional gastrointestinal disorders] symptom severity and quality of life with lasting effects…” (Aucoin et al., 2014)

From these few studies we can see that mindfulness is an accepted and potentially helpful adjunct in improving patient symptoms and quality of life in those who have bowel dysfunction. Mindfulness is a tool that every therapist should have in the toolbox for offering to patients who can complete this self-care activity as part of a home program. If you’d like to learn more about how to effectively instruct in mindfulness, you still have time to register for the Caroline McManus continuing education course on Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment, taking place January 16-17 in Silverdale, Washington, on the beautiful peninsula.

Aucoin, M., Lalonde-Parsi, M. J., & Cooley, K. (2014). Mindfulness-Based Therapies in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014.

Jedel, S., Hankin, V., Voigt, R. M., & Keshavarzian, A. (2012). Addressing the mind, body, and spirit in a gastrointestinal practice for inflammatory bowel disease patients. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 10(3), 244-246.

Jedel, S., Hoffman, A., Merriman, P., Swanson, B., Voigt, R., Rajan, K. B., ... & Keshavarzian, A. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to prevent flare-up in patients with inactive ulcerative colitis. Digestion, 89(2), 142-155.

Zomorodi, S., Abdi, S., & Tabatabaee, S. K. R. (2014). Comparison of long-term effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy versus mindfulness-based therapy on reduction of symptoms among patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from bed to bench, 7(2), 118.

While working with a 71 year old lady one day, I asked her about her sleep habits, thinking she would describe her neck position, since that it was I was treating. She quickly commented she gets up one to two times every night to use the bathroom. Without any hesitation, she then declared her sister and her friends all do the same thing. No one she knows who is close to her age can sleep through the night without having to pee. Realizing this was more of an issue for my patient than her neck at night, I proceeded to look into the research behind these nighttime escapades of the elderly.

In the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine in 2013, Zeitzer et al. performed research regarding insomnia and nocturia in older adults. The introduction explains how 40-70% of older adults experience insomnia, and the greatest cause for sleep disturbance is the need to urinate in the middle of the night (nocturia). In epidemiological studies, between two-thirds and three-quarters older adults report disrupted sleep due to nocturia. The study performed by these authors involved men (average age of 64.3) and women (average age of 62.5) recording their sleep and toileting habits over the course of 2 weeks. The results showed over half the reported awakenings at night were secondary to nocturia. They had worse restfulness and efficiency of sleep associated with the log-reported need to get up to use the bathroom.

In a 2014 study by Tyagi, et al., the effect of nocturia on the behavioral treatment for insomnia in older adults was explored. The authors noted how nocturia being the primary reason for waking up at night increased proportionately with age with results ranging from 39.9% in people 18-44 years of age to 77.1% in the 65 years old or above population. The 79 participants in this study underwent brief behavioral treatment for their chronic insomnia or only received information. People with and without nocturia both demonstrated significant improvements in quality of sleep after receiving brief behavioral treatment versus the control group; however, the effect size was larger in the participants without nocturia. The authors concluded nocturia needs to be addressed first in order to experience the full benefit of behavior treatment for insomnia.

In a 2014 study by Tyagi, et al., the effect of nocturia on the behavioral treatment for insomnia in older adults was explored. The authors noted how nocturia being the primary reason for waking up at night increased proportionately with age with results ranging from 39.9% in people 18-44 years of age to 77.1% in the 65 years old or above population. The 79 participants in this study underwent brief behavioral treatment for their chronic insomnia or only received information. People with and without nocturia both demonstrated significant improvements in quality of sleep after receiving brief behavioral treatment versus the control group; however, the effect size was larger in the participants without nocturia. The authors concluded nocturia needs to be addressed first in order to experience the full benefit of behavior treatment for insomnia.

On a neurological level, a study from November 2015 by Smith, Kuchel, and Griffiths reported there could be a neural basis for voiding dysfunction in older adults. They found 3 separate neural circuits control voiding, and damage to the pathways feeding these circuits increases with age and can increase urge incontinence. Older adults experiencing neurological deficits may have difficulty discerning what to do when there is urgency and are susceptible to becoming incontinent. The authors recommend treatment of not just the bladder in older people but also therapies to address the structural and functional abnormalities of the neural circuits to provide the greatest results.

So, the next time I saw my patient, I explained to her she is definitely not alone in her nightly rendezvous to the bathroom when it comes to her age group. She has accepted this as “just how things are.” I would like to think there is something more we can do for the elderly population to keep them out of the nocturia “night club.” Taking the Geriatric Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation course by Heather S. Rader, PT, DPT, BCB-PMD, seems like an essential step in the right direction.

Tyagi, S., Resnick, N. M., Perera, S., Monk, T. H., Hall, M. H., & Buysse, D. J. (2014). Behavioral Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Older Adults: Does Nocturia Matter? Sleep, 37(4), 681–687.

Zeitzer, J. M., Bliwise, D. L., Hernandez, B., Friedman, L., & Yesavage, J. A. (2013). Nocturia Compounds Nocturnal Wakefulness in Older Individuals with Insomnia. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 9(3), 259–262.

Smith, Phillip P., Kuchel, George A., Griffiths, Derek. (2015). Functional Brain Imaging and the Neural Basis for Voiding Dysfunction in Older Adults. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 31(4), 549–565.

Happy Tuesday! Today we are fortunate enough to hear from Stefanie Foster, who just earned her designation as a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner! Thank you for your time, Stefanie, and congratulations!

Describe your clinical practice:

I have a private practice specializing in pelvic health and related orthopedic conditions. My clinical practice is infused with my training in yoga, pelvic rehab, women’s functional nutrition, orthopedic manual physical therapy, and movement system impairment syndromes.

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

I first became curious about the pelvic floor muscles as a consequence of treating orthopedic conditions. No matter what you’re working with in that setting– back pain, hip pain, even shoulder or foot, central stability or the core is of utmost importance. I started to wonder what was going on with the respiratory diaphragm and pelvic floor when we were doing all this abdominal bracing that was (and still is in some circles) all the rage. I arranged a clinical in-service with Susan Steffes to come give us a little overview and talk about how to screen for when someone needed to see a pelvic PT. After that little hour, my interest was piqued and I knew I had to learn more…hence my first H&W class.

What/who inspired you to become involved in pelvic rehabilitation?

It was a gradual inspiration, beginning with Susan. Then, I would have to say Holly and Kathe; my experience in Level 1 forever changed my professional trajectory. As far as the “what”, clinically I am always very attracted to the zebras, the complex conditions, the things that are slipping through the cracks in the medical system, the underserved…and everything about pelvic rehabilitation is that. It’s also a big public health...uh I’ll say opportunity rather than crisis. As a profession, we are doing better, but we still have a long way to go before everyone knows what we can do. Imagine how many people we could help if EVERYONE knew?! It’s really exciting!!

What patient population do you find most rewarding in treating and why?

I love working with patients who come in with a student’s mind. The ones who are curious, ask questions, take notes, and consistently do their homework typically develop a great working relationship with me and have excellent outcomes.

If you could get a message out to physical therapists about pelvic rehabilitation what would it be?

To my former orthopedic-focus-only self and anyone in the same boat, it would be to stop pretending the pelvic floor doesn’t matter in your practice. At the very least, when you’re doing your red flag screen and ask if the patient has had any changes in bowel or bladder, stop downplaying it when the patient mentions they have had some minor leaks or constipation. Refer them to a pelvic rehab specialist! Don’t scare them, just tell them it’s common and there’s pharma-free help out there!

What has been your favorite Herman & Wallace Course and why?

Holly and Kathe taught my Level 1 and it was one of THE BEST courses I’ve ever taken (I’m not just saying that because it’s for their site!). They somehow managed to simultaneously have us rolling on the floor laughing, feeling incredibly supported and comfortable, and leave us ready to walk out the door and treat patients Monday morning. Incredible.

What is in store for you in the future?

More teaching and research. I am passionately curious about several unanswered questions and could keep myself busy the rest of my life investigating and sharing my findings. Right now, the relationship of orthopedic conditions and movement impairments of the hip with pelvic floor-related complaints has mesmerized me!

What role do you see pelvic health playing in general well-being?

If you look at the yoga tradition, the pelvic floor is our base, our ground, our safety, our manifestation into the world… Everything we work with - bladder, bowel, sexual function, birth – is so basic to life on earth! Treatment of these conditions is truly life enhancing! Without the pelvic floor and related structures functioning optimally, it’s challenging to get the rest of the system to function optimally.

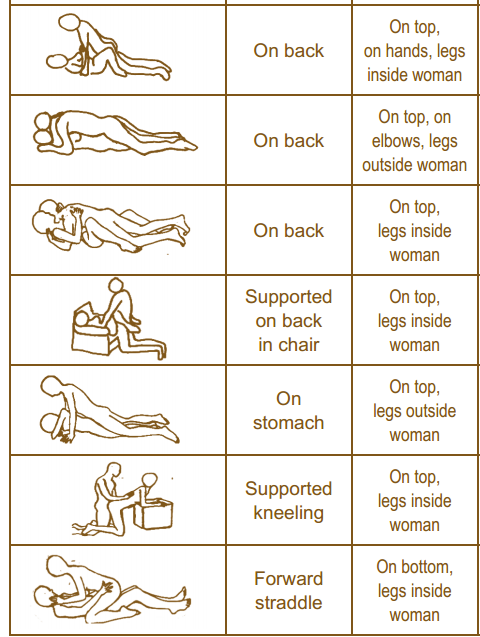

As pelvic rehab providers, we may find it easy to talk to our patients about sexual function when it is a patient who comes to us with a sexually relevant problem or directly related diagnosis, such as dyspareunia or limited intercourse participation due to prolapse symptoms. However, are we talking to our other patients about sexual function? Are they talking to us about it? What about our orthopedic patients - are we routinely asking them about how their problem can affect their sexual function? Some recent studies found that 32% of patients planning to undergo a Total Hip Replacement (THR) had reported concerns about difficulties with sexual activityBaldursson, Wright. Was the fact that they could not participate in sexual activity due to the hip pain a driving factor when considering the hip replacement, maybe? Just because a patient doesn’t ask, does not mean that they don’t want to know how their orthopedic injury affects sexual function. Resuming sexual function is an important quality of life goal that is included on few outcome assessment forms, however, there are some that address this subject such as the Oswestry Disability Index for Low Back Pain. Discussion of this topic should be addressed more routinely than it is.

It is important to remember that just because a patient is not in our office for a directly related sexual problem, it is still important to at least open up the dialogue about sexual health. One study in 2013 had patients complete a questionnaire on their sexual function after undergoing a total hip or total knee replacement and 90% reported improved overall sexual functionRathod, et al.. We should try to make the conversation part of our routinely delivered information for a total joint replacement, for example when telling our THR patient, you can resume driving at 3-6 weeks (or when cleared by surgeon), you have Range of Motion precautions of avoiding internal rotation, hip flexion past 90 degrees, and hip adduction (crossing the legs) for the length specified by your surgeon (if it was a posterior approach THR), and you can resume sexual function at 3-6 weeks (or when cleared by the surgeon), or when you feel ready after that. It is important to give the patient some kind of guideline about when they can expect to resume sexual activity, however, always emphasize that it should be resumed when the patient is ready so they don’t feel pressured before they are ready. Also as pelvic rehab practitioners we can offer them guidance about what positions may be best for them when returning to sexual activity to put less strain on the prosthesis and hip as well as help them be comfortable. To continue with our example for THR (posterior approach) their precautions are likely to restrict hip flexion past 90 degrees, hip internal rotation, and adduction, so for a man or woman following THR lying on their back would be a safe position.

As physical therapists it is our job to provide guidance. Instead of telling people what not to do, helping them find a safe way to do things they want to do to maintain function should always be our goal. Sexual activity participation is definitely an important function for quality of life that is often overlooked and not discussed, so talk to your patient about it, they will likely appreciate it.

One useful tool to learn more about positioning for sexual activity is the Herman & Wallace product “Orthopedic Considerations for Sexual Activity.” It provides a great list of positions with pros and cons of each position, and is a helpful visual aid for your patients to help them return to sexual function safely with consideration of their respective injuries.

Baldursson, H., & Brattström, H. (1979). Sexual difficulties and total hip replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology, 8(4), 214-216.

Wright, J. G., Rudicel, S. A. L. L. Y., & Feinstein, A. R. (1994). Ask patients what they want. Evaluation of individual complaints before total hip replacement. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British Volume, 76(2), 229-234.

Rathod PA, Deshmuka AJ, Ranawat AS, Rodriguez JA. Sexual function improves significantly following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective study. Program and abstracts of the 2013 meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; March 19-23, 2013; Chicago, Illinois. Poster P023.

Today we get to hear from Sherine Aubert, PT, DPT, PRPC who just earned her certification! Sherine was kind enough to share her story about discovering pelvic rehabilitation.

Tell us a bit about your clinical practice

Tell us a bit about your clinical practice

Men and women across the life span with urogynecological, colorectal, orthopedic, as well as pre and post-surgical cases including sexual reassignment surgeries make up the majority of the population I treat. Most patients are working towards improving their bedroom and bathroom issues including prolapse, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, incontinence, pelvic pain, coccydynia, voiding dysfunctions, interstitial cystitis, vaginismus and dyspareunia. Educating and setting male patients up with pre surgical prostatectomy pelvic floor muscle strengthening programs and as well as improving outcomes of patients who have undergone sexual reassignment surgeries.

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

I have always had such respect and fascination with the pelvic floor muscles. They are underestimated and overlooked in many physical therapy settings and I feel passionate about changing this! I have made it my goal to educate and empower individuals while making a comfortable environment to ask questions to further understand their anatomy, function and optimize their health.

What/who inspired you to become involved in pelvic rehabilitation?

I have been very lucky to have many wonderful influences in my academic and professional career. The two pelvic floor “geniuses” who have always had time to discuss new treatments, brainstorm, and optimize my skill set would be Dr. Chris Eddow PT, DPT, OCS, WCS, CHT and Dr. Jamie Taylor PT, DPT. Thanks for always pushing me to the next level ladies, I look forward to advancing the pelvic floor world with you gals!

What do you find is the most useful resource for your practice?

During every initial evaluation I use a pelvic model to show all the pelvic floor muscles, organs and connective tissue with an overview of anatomy and function. I find patients are very appreciative of the explanation and find extreme value in understanding their own anatomy. Every time I show the model, I feel like I am sharing the world’s best secret about their bodies!

What motivated you to earn PRPC?

I appreciated the fact that "PRPC" included men and women's knowledge base.

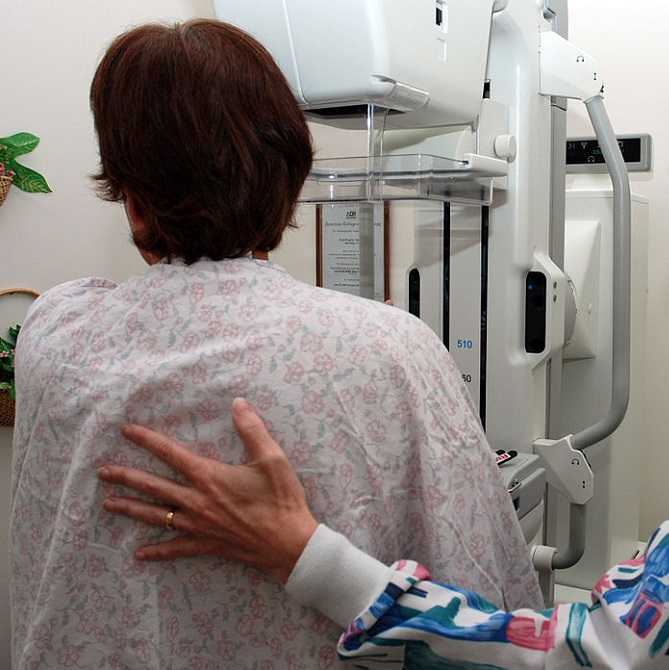

My first experience treating a patient with shoulder pain and limitations post-mastectomy just happened to be a local doctor’s sister. Luckily, I did not know this until a few sessions into her therapy. Ultimately, even more than normal, this patient’s outcome was a make or break situation for a future referral source. Her incredible spirit and optimism made the prognosis an inevitably positive one. Whether or not I had manual therapy training was a moot point, according to current research; however, from my perspective, I would not have been as competent in treating her without it.

In June 2015, De Groef et al. performed a review of literature to investigate the efficacy of physical therapy for upper extremity impairments after surgical intervention for breast cancer. Eighteen randomized controlled studies were chosen for review regarding the efficacy of passive mobilization, myofascial therapy, manual stretching, and/or exercise therapy after breast cancer treatment. In the studies reviewed, physical therapy began at least 6 weeks post-surgical intervention. Combining general exercise with stretching was confirmed effective on range of motion (ROM) by 2 studies. One study showed the effect of passive mobilization with massage was null for pain or impaired ROM. No study showed any effect of myofascial therapy, one poor quality study supported the use of passive mobilization alone, and one study showed no effect of stretching alone. Active exercises were found more effective than no therapy or simply education in five studies. Early intervention was found to be beneficial for shoulder ROM in 3 studies, but 4 other studies supported delayed exercise to promote wound healing longer. Ultimately, pain and impaired shoulder ROM after operative treatment for breast cancer have been treated effectively by a multifactorial approach of stretching and active exercise. The efficacy of passive mobilization, stretching, and myofascial therapy needs to be investigated with higher quality research in the future.

In June 2015, De Groef et al. performed a review of literature to investigate the efficacy of physical therapy for upper extremity impairments after surgical intervention for breast cancer. Eighteen randomized controlled studies were chosen for review regarding the efficacy of passive mobilization, myofascial therapy, manual stretching, and/or exercise therapy after breast cancer treatment. In the studies reviewed, physical therapy began at least 6 weeks post-surgical intervention. Combining general exercise with stretching was confirmed effective on range of motion (ROM) by 2 studies. One study showed the effect of passive mobilization with massage was null for pain or impaired ROM. No study showed any effect of myofascial therapy, one poor quality study supported the use of passive mobilization alone, and one study showed no effect of stretching alone. Active exercises were found more effective than no therapy or simply education in five studies. Early intervention was found to be beneficial for shoulder ROM in 3 studies, but 4 other studies supported delayed exercise to promote wound healing longer. Ultimately, pain and impaired shoulder ROM after operative treatment for breast cancer have been treated effectively by a multifactorial approach of stretching and active exercise. The efficacy of passive mobilization, stretching, and myofascial therapy needs to be investigated with higher quality research in the future.

Another review of literature in 2010 by McNeely et al. used 24 studies to analyze the effectiveness of exercise intervention for upper extremity impairments after breast cancer surgical intervention. Ten of the studies focused on early versus late intervention, and all supported the earlier implementation of post-surgical exercises for ROM; however, wound drain volume and duration were increased in the subjects engaged in earlier exercises. Fourteen studies showed structured exercise intervention improved shoulder ROM significantly in the post-op period, and a 6-month follow up continued to show improved upper extremity function. No lymphedema risk was noted in any of the studies.

As with many areas of physical therapy, better research is needed to support what we do. We often treat with success in the clinic despite lack of strength in the evidence-based realm. After implementing glenohumeral and scapulothoracic mobilizations, soft tissue work in the posterior cervical and scapular muscles (avoiding lymph nodes), stretching, progressive resisted strengthening, and a home program, my patient regained full range of motion and function of the affected shoulder after her mastectomy. In retrospect, I should have written up a case study on this patient to contribute to our profession. At least after my patient was discharged, the clinic where I worked received a healthy supply of future referrals from her sister because of the positive results achieved with therapy.

If you are interested in learning evaluation and treatment techniques which can benefit breast oncology patients, consider a Herman & Wallace Physical Therapy Treatment for the Breast Oncology Patient course in 2016.

De Groef A, Van Kampen M, Dieltjens E, Christiaens MR, Neven P, Geraerts I, Devoogdt N. (2015). Effectiveness of postoperative physical therapy for upper-limb impairments after breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 96(6):1140-53. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.01.006. Epub 2015 Jan 13.

McNeely ML, Campbell K, Ospina M, Rowe BH, Dabbs K, Klassen TP, Mackey J, Courneya K. (2010). Exercise interventions for upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. The Cochrane Database System of Reviews. (6):CD005211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005211.pub2.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://hermanwallace.com./