What if we were only taught treatment techniques during our healthcare training with no theory or explanation as to why or on whom or under what circumstances they should be used? Focusing on “how to” but ignoring the “discernment as to why” would make for a weak clinician. Manual therapy for the pelvic floor is a treatment approach to implement once we have used our heads and palpation skills to reveal the underlying source of dysfunction.

Pastore and Katzman (2012) published a thorough article describing the process of recognizing when myofascial pain is the source of chronic pelvic pain in females. They discuss active versus latent myofascial trigger points (MTrPs), which are painful nodules or lumps in muscle tissue, with the latter only being symptomatic when triggered by physical (compression or stretching) or emotional stress. Hyperalgesia and allodynia are generally present in patients with MTrPs, and muscles with MTrPs are weaker and limit range of motion in surrounding joints. In pelvic floor muscles, MTrPs refer pain to the perineum, vagina, urethra, and rectum but also the abdomen, back, thorax, hip/buttocks, and lower leg. The authors suggest detecting a trigger point by palpating perpendicular to the muscle fiber to sense a taut band and tender nodule and advise using the finger pads with a flat approach in the abdomen, pelvis and perineum. They emphasize a multidisciplinary approach to finding and treating MTrPs and making sure urological, gynecological, and/or colorectal pathologies are addressed. A thorough subjective and physical exam that leads to proper diagnosis of MTrPs should be followed by manual physical therapy techniques and appropriate medical intervention for any corresponding pathology.

Halder et al. (2017) investigated the efficacy of myofascial release physical therapy with the addition of Botox in a retrospective case series for women with myofascial pelvic pain. Fifty of the 160 women who had Botox and physical therapy met the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the primary complaint in all those subjects was dyspareunia. The Botox was administered under general anesthesia, and then the same physician performed soft tissue myofascial release transvaginally for 10-15 minutes, with 10-15 additional minutes performed if rectus muscles had trigger points. The patients were seen 2 weeks and 8 weeks posttreatment. Average pelvic pain scores decreased significantly pre- and posttreatment, with 58% of subjects reporting improvements. Significantly fewer patients (44% versus 100%) presented with trigger points on pelvic exam after the treatment. The patients who did not show improvement tended to have inflammatory or irritable bowel diseases or diverticulosis. Blocking acetylcholine receptors via Botox in combination with pelvic floor physical therapy could possibly provide longer symptom-free periods. Although the nature of the study could not determine a specific interval of relief, the authors were encouraged as an average of 15 months passed before 5 of the patients sought more treatment.

The need for the specific treatment for myofascial pelvic pain is determined by a clinician competent in palpation of the pelvic floor musculature finding trigger points and restrictions in the tissue. Listening to a patient’s symptoms and understanding pelvic pathology allow for better treatment planning. Manual Therapy Techniques for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist is a comprehensive course to enhance knowledge in your head to lead your hands in the right direction for assessing/treating patients with pelvic pain.

Pastore, E. A., & Katzman, W. B. (2012). Recognizing Myofascial Pelvic Pain in the Female Patient with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing : JOGNN / NAACOG, 41(5), 680–691. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01404.x

Halder, G. E., Scott, L., Wyman, A., Mora, N., Miladinovic, B., Bassaly, R., & Hoyte, L. (2017). Botox combined with myofascial release physical therapy as a treatment for myofascial pelvic pain. Investigative and Clinical Urology, 58(2), 134–139. http://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2017.58.2.134

While running on my treadmill, I watched a commercial advertising specially designed pads as “the solution” for women athletes who “leak” during their sport. Before my introduction to Herman and Wallace Rehabilitation Institute, I would have rushed to the nearest store to buy a case of them. When we don’t know how to fix a problem, we tend to cling to bandages to cover them, allowing us to ignore them. With 29 years of running and racing and 2 natural childbirths under my belt, leaks have happened, and it is common. However, leaks due to urinary stress incontinence are not normal and do not stop simply because you place a contoured, sporty, sanitary pad in the lining of your shorts.

A 2016 cross-sectional study by Ameida et al. investigated urinary incontinence (UI) and pelvic floor dysfunctions (PFD) such as constipation, anal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, vaginal laxity, and dyspareunia in female athletes who participate in high-impact sports. The 67 amateur athletes and 96 non-athletes completed an ad hoc survey to determine PFD symptoms. Artistic gymnasts, trampolinists, swimmers, and judo participants were among the athletes with the highest risk of urinary incontinence. Although the athletes had a higher risk of UI, they reported less constipation, less straining to relieve themselves, and less manual assistance for defecation than the non-athletes. The authors were able to conclude that high impact sports or sports requiring a strong effort put athletes at risk for UI, uncontrolled gas expulsion, and even sexual dysfunction. They emphasize a need for attention to be given to pelvic floor training for rehabilitation as well as preventative strategies and education for high risk yet asymptomatic athletes.

A 2016 cross-sectional study by Ameida et al. investigated urinary incontinence (UI) and pelvic floor dysfunctions (PFD) such as constipation, anal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, vaginal laxity, and dyspareunia in female athletes who participate in high-impact sports. The 67 amateur athletes and 96 non-athletes completed an ad hoc survey to determine PFD symptoms. Artistic gymnasts, trampolinists, swimmers, and judo participants were among the athletes with the highest risk of urinary incontinence. Although the athletes had a higher risk of UI, they reported less constipation, less straining to relieve themselves, and less manual assistance for defecation than the non-athletes. The authors were able to conclude that high impact sports or sports requiring a strong effort put athletes at risk for UI, uncontrolled gas expulsion, and even sexual dysfunction. They emphasize a need for attention to be given to pelvic floor training for rehabilitation as well as preventative strategies and education for high risk yet asymptomatic athletes.

In 2015, DaRoza et al. performed a cross-sectional cohort study to determine the urinary leakage in 22 young female trampolinists based on the volume of their training and level of ranking. Leakage was assessed by the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Short-Form (ICIQ-UI-SF), and another questionnaire determined each athlete’s championship ranking and training volume. An astounding 72.7% of girls reported urine leakage since starting to perform on the trampoline, and the greatest severity was significantly associated with the highest training volume. The impact of UI on the athlete’s quality of life was greatest in this 3rd tertile. The authors recommended these athletes with a high frequency of UI be educated on the impact of their sport on their pelvic floor muscles and proposed they get treated by pelvic health professionals to minimize or resolve the incontinence.

Thankfully, none of the above researchers or medical professionals advises the study participants to just use a pad and carry on with their sport. Urinary incontinence is a real problem in athletes, and its prevalence is appalling. Even young girls without any birthing of babies to blame are leaking. Making females (and males) aware of the impact sports can have on their pelvic floor and educating them that urinary leakage is not normal are essential missions for healthcare professionals. “The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor” course can help integrate pivotal aspects of pelvic rehabilitation into sports medicine, as some conditions just may require training to move down to the pelvic floor for complete recovery.

Almeida, MB, Barra, AA, Saltiel, F, Silva-Filho, AL, Fonseca, AM, Figueiredo, EM. (2016). Urinary incontinence and other pelvic floor dysfunctions in female athletes in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 26(9):1109-16. http://doi:10.1111/sms.12546

Da Roza, T, Brandão, S, Mascarenhas, T, Jorge, RN, Duarte JA. (2015). Volume of training and the ranking level are associated with the leakage of urine in young female trampolinists. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 25(3):270-5. http://DOI:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000129

While recently visiting Seattle with my daughter, we had the pleasure of talking with Dr. Ghislaine Robert, owner of Sparclaine Regenerative Medicine. She is a highly respected sports medicine doctor who has steered much of her practice towards regenerative medicine, with a focus on stem cell and platelet enriched plasma (PRP) injections. She brought to my attention the use of stem cells for pelvic floor disorders. And, like any successful practitioner, she encouraged me to research it for myself.

In 2015, Cestaro et al. reported early results of 3 patients with fecal incontinence receiving intersphincteric anal groove injections of fat tissue. They aspirated about 150ml of the fat tissue and used the Lipogem system technology lipofilling technique to provide micro-fragmented and transplantable clusters of lipoaspirate. The intersphincteric space was then injected with the lipoaspirate. A proctology exam was performed at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 months following the procedure. All 3 patients all had reduced Wexner incontinence scores 1 month post-treatment and a significant improvement in quality of life 6 months post-procedure. Resting pressure of the internal anal sphincter increased after 6 months, and the internal anal sphincter showed increased thickness.

A 2016 study by Mazzanti et al., used rats to explore whether unexpanded bone marrow-derived mononuclear mesynchymal cells (MNC) could effectively repair anal sphincter healing since expanded ones (MSC) had already been shown to enhance healing after injury in a rat model. They divided 32 rats into 4 groups: sphincterotomy and repair (SR) with primary suture of anal sphincters and a saline intrasphincteric injection (CTR); SR of anal sphincter with in-vitro expanded MSC; SR of anal sphincter with minimally manipulated MNC; and, a sham operation with saline injection. Muscle regeneration as well as contractile function was observed in the MSC and MNC groups, while the control surgical group demonstrated development of scar tissue, inflammatory cells and mast cells between the ends of the interrupted muscle layer 30 days post-surgery. Ultimately, the authors found no significant difference between expanded or unexpanded bone marrow stem cell types used. Post-sphincter repair can be enhanced by stem cell therapy for anal incontinence, even when the cells are minimally manipulated.

Finally, in 2017, Sarveazad et al. performed a double-blind clinical trial in humans using human adipose-derived stromal/stem cells (hADSCs) from adipose tissue for fecal incontinence. The hADSCs secrete growth factor and can potentially differentiate into muscle cells, which make them worth testing for improvement of anal sphincter incontinence. They used 18 subjects with sphincter defects, 9 undergoing sphincter repair with injection of hADSCs and 9 having surgery with a phosphate buffer saline injection. After 2 months, there was a 7.91% increase in the muscle mass in the area of the lesion for the cell group compared to the control. Fibrous tissue replacement with muscle tissue, allowing contractile function, may be a key in the long term for treatment of fecal incontinence.

As long as accessing human-derived stem cells is a viable option for patients, the preliminary studies show promise for success. With fecal incontinence being such a debilitating problem for people, especially socially, stem cells are definitely an up and coming treatment, and we should all keep up on this research. After all, who wouldn’t spare some adipose tissue for life-changing, functional gains?

Cestaro, G., De Rosa, M., Massa, S., Amato, B., & Gentile, M. (2015). Intersphincteric anal lipofilling with micro-fragmented fat tissue for the treatment of faecal incontinence: preliminary results of three patients. Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques, 10(2), 337–341. http://doi.org/10.5114/wiitm.2014.47435

Mazzanti, B., Lorenzi, B., Borghini, A., Boieri, M., Ballerini, L., Saccardi, R., … Pessina, F. (2016). Local injection of bone marrow progenitor cells for the treatment of anal sphincter injury: in-vitro expanded versus minimally-manipulated cells. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 7, 85. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-016-0344-x

Sarveazad, A., Newstead, G. L., Mirzaei, R., Joghataei, M. T., Bakhtiari, M., Babahajian, A., & Mahjoubi, B. (2017). A new method for treating fecal incontinence by implanting stem cells derived from human adipose tissue: preliminary findings of a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 8, 40. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-017-0489-2

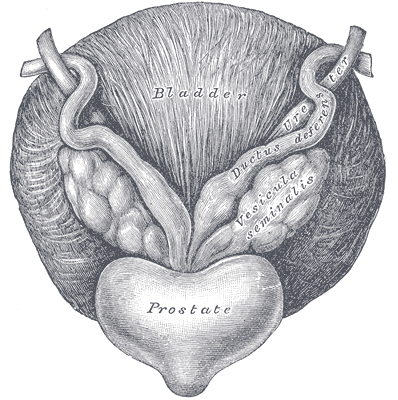

The Center for Disease Control reports that prostate cancer is the most common form of male cancer in the United States (just ahead of lung cancer and colorectal cancer), and the American Cancer Society estimates that 1 in 7 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point in their lifetime. With prostate cancer being so common, it is likely that a male with symptoms of urinary incontinence following a prostatectomy may show up at your clinic’s door for treatment. What do you do? Whether you have extensive training for male pelvic floor disorders or are just starting your initial training for pelvic floor dysfunctions, you likely have some intervention skills to help this population.

A recent case report in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, outlines management of a 76-year-old male patient with mixed urinary incontinence postprostatectomy 10 years. This case report does a nice job describing not just physical therapy (PT) interventions, but also multifaceted management of a typical patient post radical prostatectomy. The case report describes a thorough history, systems review, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) examination, tests &measures, and outcome assessment. Our discussion will focus on interventions as you may already possess the skills for several of the treatments included in this patient’s plan of care.

A recent case report in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, outlines management of a 76-year-old male patient with mixed urinary incontinence postprostatectomy 10 years. This case report does a nice job describing not just physical therapy (PT) interventions, but also multifaceted management of a typical patient post radical prostatectomy. The case report describes a thorough history, systems review, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) examination, tests &measures, and outcome assessment. Our discussion will focus on interventions as you may already possess the skills for several of the treatments included in this patient’s plan of care.

The patient’s complaints were mixed urinary incontinence (UI) symptoms including 3-4 pads per day and 1 pad at night. He reported nocturia 3-4 times per night. 2-3 times per week he had large UI episodes that soaked his outwear. Also, he complained of inability to delay voiding, and UI with walking to the bathroom, sit to stand, lifting, coughing, and sneezing.

For the patients’ urge UI symptoms, behavioral interventions were utilized. The patient completed PFM contractions to inhibit detrusor contractions and suppress urgency (urge control technique). Educating the patient on correct PFM contraction isolation was a very important component of this patients’ treatment. Verbal, digital, and surface electromyography (sEMG) techniques were used to ensure correct PFM contraction and to reduce Valsalva. Clinical decision making for home exercise program utilized dominant PFM fiber types and the patients’ performance on the PERFECT PFM strength testing system described by Laycock. (External Urethral Sphincter is predominantly Type II fast twitch muscle fiber in males and Levator Ani is predominantly Type I slow twitch.) For the home program, the patient completed progressive reps and sets of 10” (targets slow twitch) and 2” (targets fast twitch) PFM isometrics in supine progressing to standing. (There is a chart with additional details on PFM home program for each visit in the case report.) Additionally, instruct and use of “the knack” (volitional PFM contraction before and during cough or other physical exertions to prevent UI) for activities that the patient usually had UI with including sit to stand transfer, lifting, coughing, and sneezing was essential for the patients’ symptoms. PFM coordination training with sEMG helped reduce his accessory muscle recruitment patterns and Valsalva. Bladder retraining and lifestyle recommendation were important (per his 3-day bladder diary) as he was consuming 3 cups of coffee and 4 cups or more of tea a day, likely contributing to urgency and urge UI symptoms. Also, he was informed regarding the effect of obesity on UI (as his BMI was 35.9 placing him in the obese range) and that modest amounts of weight loss maybe sufficient for UI reduction. Abdominal exercises targeting Transversus Abdominus were also prescribed for their role in core support with PFM’s. Lastly, electrical stimulation was not included in this patients’ plan of care due to the patients’ cardiac history and pacemaker, as well as, he could initiate PFM contraction and utilize urge control techniques appropriately.

The outcome for this patient was positive. He attended 5 PT sessions over a 3-month period. He did have to cancel two appointments between the 4th and 5th visits due to an emergency surgery to place two cardiac stents. He had reduced urinary leakage indicated by reduced undergarment changes and reduced pad usage per day. His pads were less saturated and he no longer had leakage that spread to his outwear. He had a 50% reduction in UI episodes reported on his bladder diary and a 50% reduction in nocturia from 4 times to 2 times per night. He reported reduced daily urinary frequency from 7 to 5 times per day with no instances of severe urgency. He demonstrated improved PERFECT score of 4, 10, 8, 10 (initially his score was 2, 5, 3, 5) indicating improved PFM strength and endurance. Also, he had improved PFM coordination as he could isolate PFM contraction without Valsalva or accessory muscle activation. He also had one strength grade improvement with abdominal strength. All that being said, most importantly, this patient had improved rating on the outcome questionnaire (International Continence Society male Short Form (ICSmaleSF)) at discharge indicating improved quality of life. At initial evaluation, this patient rated “a lot” (3 on ICSmaleSF) when asked how much the urinary symptoms interfered with his life, at discharge he reported “not at all” (0 on ICSmaleSF).

One component to this case that I found fascinating was the duration of time that had passed since this patients’ prostatectomy. It had been 10 years since this patient had his surgical procedures. He had never been offered physical therapy or knew about it as a possible treatment for his symptoms. Additionally, that he could have such success with improvements in voiding and incontinence function, as well as improved quality of life as long as 10 years’ post-prostatectomy.

This case report is a comprehensive glimpse of what physical therapy assessment and treatment may look like for a patient with urinary dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. This patient had great improvements with positive changes enhancing his quality of life. So, if you are considering adding treatment of this population to your practice consider attending Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation, available this July in Annapolis, MD or September in Seattle, WA.

"Cancer Among Men", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Roscow, A. S., & Borello-France, D. (2016). Treatment of Male Urinary Incontinence Post–Radical Prostatectomy Using Physical Therapy Interventions. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 40(3), 129-138.

Male Pelvic Pain: What Therapists Can Do to Help End the Desperation

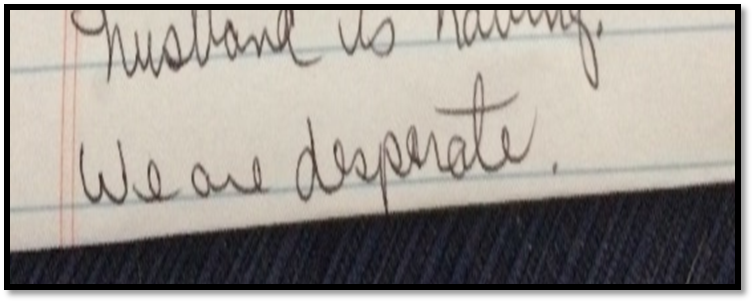

Recently, a note was left at my doorstep by the wife of an older gentleman who had chronic male pelvic pain. His pain was so severe, he could not sit, and he lay in the back seat of their idling car as his wife, having exhausted all other medical channels available to her, walked this note up to the home of a rumored pelvic floor physical therapist who also treated men. The note opened with how she had heard of me. She then asked me to contact her about her husband’s medical problem. It ended with three words that have vexed me ever since…we are desperate.

Unlike so many men with chronic pelvic pain, he had at least been given a diagnostic cause of his pain, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, rather than vaguely being told it was just a prostate issue. However, the therapists that had been recommended by his doctor only treated female pelvic dysfunction.

“We are desperate”: A Call to Action for All Therapists to become Pelvic Floor Inclusive

My first thought after reading the note was, “I bet shoulder or knee therapists don’t get notes like this on their doorstep.” My next thought, complete with facepalm, “THIS HAS TO STOP! Pelvic floor rehab has got to become more accessible”.

Pelvic floor therapists see men and women and even transgenders. They treat in the pediatric, adult, and geriatric population. They treat pelvic floor disorders in the outpatient, home health and SNF settings. They treat elite athletes and those with multiple co-morbidities using walkers. They can develop preventative pelvic wellness programs and teach caregivers how to better manage their loved one’s incontinence. This is due to one simple fact: No matter the age, gender, level of health or practice setting, every patient has a pelvic floor.

The pelvic floor should not be regarded as some rare zebra in clinical practice when it is the workhorse upon which so many health conditions ride. It interacts with the spine, the hip, the diaphragm, and vital organs. It is composed of skin, nerves, muscles, tendons, bones, ligaments, lymph glands, and vessels. It is as complex and as vital to function and health as the shoulder or knee is, and yet students are lucky if they get a “pelvic floor day” in their PT or OT school coursework.

I call for every therapist, specialist, and educator to learn more about the pelvic floor. Here are some steps you can take today toward eliminating the need for such a note to be written.

If you are a pelvic floor therapist who treats men, shout it from the rooftops!

Contact every PT clinic, every SNF, every doctor, every nurse, every chiropractor, every acupuncturist, every massage therapist, every personal trainer, every community group and let them know! If you have already told them, tell them again. Send a one page case study with your business card. Host a free community health lecture at the library or VFW hall. Keep the conversation going. Reach out to your local rehab or nursing school programs and volunteer to speak to the students. Feature pelvic health topics in your clinic’s social media stream. Get on every single therapist locator that you can so people can find you. Click here to go to the Herman and Wallace Find a Practitioner site.

If you only treat pelvic dysfunction in women, please consider expanding your specialty to include men.

The guys really need your help. You literally may be the only practitioner around that has the skills to treat these types of problems. Yes, the concerns you have about privacy and feeling comfortable are valid. But, you are not alone in this. Smart people like Holly Tanner have figured all that stuff out for you and can guide you on how to expertly treat in the men’s health arena. Sign up for Male Pelvic Floor or take an introductory course online at Medbridge. If you have only taken PF1, it’s time to sign up for Pelvic Floor Level 2A: Function, Dysfunction and Treatment: Colorectal and Coccyx Conditions, Male Pelvic Floor, Pudendal Nerve Dysfunction. Reach out to other pelvic floor therapists that treat men and ask for mentorship.

If you are general population therapist, consider taking a pelvic floor course.

Good news! Not every pelvic floor course requires you to glove up and donate your pelvis to science, so to speak. Yes, there are several external only courses you can take that do not have an internal examination lab. Click here and look under “course format” to see a list of external only courses. If you treat in the outpatient, ortho, or sports medicine arena, consider taking Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis: Manual Movement Therapy and the Myofascial Sling System or the Athlete and the Pelvic Floor .

If you treat in the Medicare age population, work in skilled nursing, or home health, join me in New York on May 21-22 for Geriatric Pelvic Floor. It is an external course and we cover documentation and self-care strategies extensively for incontinence and pelvic pain in older adults across multiple settings. Older adults with pelvic pain, like the man in the back seat, are at risk for being diagnostically ignored. We will address biases, such as “prostato-centric” thinking, ageism, and the ever-present “no fracture no problem” prognosis given to seniors who sustain a fall, but are left with disabling soft tissue dysfunction.

If you are a PT or OT school educator, eliminate “Pelvic Floor Day”.

Sorry, but it sounds silly. It’s like saying you offer a “Knee Day” in your program. Replace it by including the pelvic floor into Every. Single. Class…anatomy, ther ex, neuro, peds, geriatrics, and even cardiopulmonary!

As the baby boomer population grows, pelvic floor disorders are expected to rise significantly (download a free white paper on pelvic floor trends here). Are you preparing your doctorate students to be competent screeners of pelvic floor dysfunction? Pelvic floor rehab is becoming the gold standard of first line treatments for pelvic dysfunction. Are you giving your students the skills to be competitive in a job market that recognizes pelvic floor rehabilitation as standard of care? Bias is learned. Excluding the pelvic floor in your student’s coursework or presenting it as a niche specialty subtly reinforces this bias.

Reach out and ask your local pelvic floor therapists to guest lecturer throughout the program. Send your instructors to pelvic floor courses. Encourage your students to take Pelvic Floor Level 1 in their last 6 months of coursework. Offer a clinical rotation in pelvic floor rehabilitation. Include case studies and patient perspectives on pelvic dysfunction, such as A Patient’s Pelvic Rehab Journey.

The Silver Lining

Thanks to the champions of pelvic floor rehab education, we’ve come a long way. The good news in this story is that this man’s doctor recognized early that he had pelvic floor muscle dysfunction and recommended that he see a pelvic floor physical therapist. The bad news-it took 2 years before he could find one. The ball is in our court, therapists. Let’s do better. Until there are no more men in the back seat, we still need to #LearnMoreAboutThePelvicFloor.

After my Dad’s 3rd trip to the emergency room not being able to breathe because of his sleep apnea and congestive heart failure, his cardiologist recommended he ”just relax” when his suffocating feelings occurred. Of course, not being able to catch his breath would always heighten anxiety, which made it even more difficult to inhale and exhale. Ultimately, what my Dad needed to learn was mindfulness to deal with his relatively benign inability to breathe, since the focus of mindfulness is acceptance of rather than control over your circumstances.

The concept of mindfulness has been studied in adults, but it is gaining popularity among the pediatric population. Ruskin et al., (2017) used a prospective pre-post interventional study to assess how children with chronic pain respond to mindfulness-based interventions (MBI’s). For 8 weeks, 21 adolescents engaged in group sessions of MBI. Before, after, and 3 months post-treatment, the authors collected self-report measurements for a variety of factors such as disability, anxiety, pain quality, acceptance, catastrophizing, and social support. Subjects were highly satisfied with the treatment, and all would recommend the group intervention to friends. From baseline to 3-month follow-up, pain acceptance, body awareness, and ability to cope with stress all improved in the subjects. Further randomized controlled studies are needed, but the initial conclusion was MBI’s were received well by adolescents.

The concept of mindfulness has been studied in adults, but it is gaining popularity among the pediatric population. Ruskin et al., (2017) used a prospective pre-post interventional study to assess how children with chronic pain respond to mindfulness-based interventions (MBI’s). For 8 weeks, 21 adolescents engaged in group sessions of MBI. Before, after, and 3 months post-treatment, the authors collected self-report measurements for a variety of factors such as disability, anxiety, pain quality, acceptance, catastrophizing, and social support. Subjects were highly satisfied with the treatment, and all would recommend the group intervention to friends. From baseline to 3-month follow-up, pain acceptance, body awareness, and ability to cope with stress all improved in the subjects. Further randomized controlled studies are needed, but the initial conclusion was MBI’s were received well by adolescents.

A feasibility study performed by Anclair, Hjärthag, and Hiltunen in 2017 considered the effect of mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy for the parents of children with chronic conditions, looking at Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL), measured with Short Form-36 (SF-36), and life satisfaction. Ten parents received group-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and 9 participated in a group-based mindfulness program (MF). Treatment was implemented for 2-hour weekly sessions over the course of 8 weeks. The CBT treatment was based on the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, focusing on changing thoughts and emotions about stressful issues as well as behaviors. They avoided the acceptance aspect, as it would overlap the MF intervention. The MF therapy used the Here and Now Version 2.0 (including daily themes on knowing your body, observing breathing, acceptance, meditation, coping, understanding thoughts versus facts, and self-care reinforcement). The parents in each group significantly improved their Mental Component Summary (MCS), Vitality, Social functioning, and Mental health scores. The MF group even showed notable improvement in Role emotional and some of the physical subscales (Bodily pain, General health, and Role physical). The CBT group showed improved satisfaction with Spare time and Relation to partner, and CBT and MF groups improved life satisfaction Relation to child. The authors conclude CBT and MF may positively affect HRQOL and life satisfaction of parents with chronically ill children.

Whether young or old or in between, how we perceive stressful situations and chronic pain can impact our health. The neurodevelopmental aspect of mindfulness is still being studied. The “Mindfulness Based Pain Treatment” course applies the concept to treating chronic pain patients. This approach brings to mind the Serenity Prayer by Reinhold Niebuhr: “Lord grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Ruskin ,DA, Gagnon, MM, Kohut SA, Stinson JN, Walker KS. (2017). A Mindfulness Program Adapted for Adolescents With Chronic Pain: Feasibility, Acceptability, and Initial Outcomes. The Clinical Journal of Pain. http://www.doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000490

Anclair, M., Hjärthag, F., & Hiltunen, A. J. (2017). Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Mindfulness for Health-Related Quality of Life: Comparing Treatments for Parents of Children with Chronic Conditions - A Pilot Feasibility Study. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health : CP & EMH, 13, 1–9. http://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901713010001

Consider combing long, curly hair. Untangling the top layer is not so bad, but once half the hair is tamed, there is often a mangled mess lurking underneath. Sometimes the lumbar spine gets all the primping to relieve pain, but the sacroiliac joint is harboring the knots, such as when a lumbar rhizotomy leaves a patient’s satisfaction a little fuzzy.

A 2017 study by Rimmalapudi and Kumar investigated the incidence of sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction being diagnosed in patients after undergoing lumbar radiofrequency rhizotomy of the medial branches of lower lumbar dorsal rami for chronic facet-mediated low back pain. The authors used a retrospective chart review of 96 patients who had the procedure performed, and 50 subjects responded to the 2 follow ups and were included in the study. Their choice of control was a limitation in this study, as they compared the results to a different study (DePalma et al., 2011) with a similar population that did not have the lumbar rhizotomy performed. Of the 50 patients (66% female, 34% male), 35 (70%) were subsequently diagnosed with SI joint pain; whereas, in the comparison study, only 18% of the patients had SI pain. The assessment of SI dysfunction in this study was by clinical exam, and the DePalma et al. study used diagnostic tests. The authors concluded the following: clinicians should suspect underlying SI joint pain post-lumbar rhizotomy; careful evaluation of the SI joint should be performed pre and post procedure; and, diagnostic joint blocks should be performed to confirm SI dysfunction. They suggested using criteria of 80-100% relief as opposed to the currently accepted >50% after a diagnostic facet block because residual pain from an underlying condition may arise after lumbar rhizotomy.

A 2017 study by Rimmalapudi and Kumar investigated the incidence of sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction being diagnosed in patients after undergoing lumbar radiofrequency rhizotomy of the medial branches of lower lumbar dorsal rami for chronic facet-mediated low back pain. The authors used a retrospective chart review of 96 patients who had the procedure performed, and 50 subjects responded to the 2 follow ups and were included in the study. Their choice of control was a limitation in this study, as they compared the results to a different study (DePalma et al., 2011) with a similar population that did not have the lumbar rhizotomy performed. Of the 50 patients (66% female, 34% male), 35 (70%) were subsequently diagnosed with SI joint pain; whereas, in the comparison study, only 18% of the patients had SI pain. The assessment of SI dysfunction in this study was by clinical exam, and the DePalma et al. study used diagnostic tests. The authors concluded the following: clinicians should suspect underlying SI joint pain post-lumbar rhizotomy; careful evaluation of the SI joint should be performed pre and post procedure; and, diagnostic joint blocks should be performed to confirm SI dysfunction. They suggested using criteria of 80-100% relief as opposed to the currently accepted >50% after a diagnostic facet block because residual pain from an underlying condition may arise after lumbar rhizotomy.

Stelzer et al., (2017) published another retrospective study on lumbar neurotomy or SI joint lateral branch cooled radiofrequency (RF) neurotomy, looking at pain reduction and medication decrease, depending on BMI, gender, and sports. Facet-mediated pain is accountable for 31-45% of low back pain, and 18-30% is SI joint mediated. The study started with 160 patients who had undergone procedures, and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scores, quality of life, BMI, medication use, and pain management satisfaction were assessed before, 1 month after (n=160), 6 months after (n=73), and 12 months (n=89) after treatment. Group 1 (n=43) had neurotomy of the medial branch of L4-5 and L5-S1 facet joint, medial branch L3 and L4, and dorsal ramus L5. Group 2 (n=109) received cooled RF treatment of the SIJ, SIJ lateral branch of the posterior rami S1–S3, and rami dorsalis of L5. Group 3 (n=8) had various areas treated according to their disease process. The authors determined from these treatments that a 95% probability of significant pain reduction could last 12 months; medication usage decreased; lower BMI had slightly better results than >30BMI; no significant difference between males and females; and, involvement in sports 1-3 times a week for 30 minutes showed improvement in quality of life.

These studies prove we need to evaluate our lumbar and sacroiliac joint patients as thoroughly as possible in order to avoid unnecessary procedures or at least to help direct the treatment to the appropriate area. We should always equip ourselves with knowledge of medical procedures our patients may undergo and expand our own clinical competence and skill. Patients benefit from what is inside our heads and how we use it, not how well-groomed our hair appears.

Rimmalapudi, V. K., & Kumar, S. (2017). Lumbar Radiofrequency Rhizotomy in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Increases the Diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction in Subsequent Follow-Up Visits. Pain Research & Management, 2017, 4830142. http://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4830142

M. J. DePalma, J. M. Ketchum, and T. Saullo. (2011). What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Medicine. 12(2), 224–233.

Stelzer, W., Stelzer, V., Stelzer, D., Braune, M., & Duller, C. (2017). Influence of BMI, gender, and sports on pain decrease and medication usage after facet–medial branch neurotomy or SI joint lateral branch cooled RF-neurotomy in case of low back pain: original research in the Austrian population. Journal of Pain Research, 10, 183–190. http://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S121897

An 80 year old lady who had seen a physical therapist where I once worked in Naperville, IL, just completed a marathon and a 5k race in one weekend. She is undoubtedly one woman who can change our perception of the “elderly,” but we all know her strength and ability are not the norm. The geriatric patients coming to therapy for pelvic floor disorders are more likely to be too frail to have run a mile this century, and they are most likely struggling with functional ADLs, as research suggests.

A study by Erekson et al., (2015) looked into the prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability among women over 65 years of age looking for the best treatment for their pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). A major concern was the presence of frailty being equated with poorer surgical outcomes. The 150 women in the study were tested with the Fried Frailty Index to measure frailty, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Score for cognitive screening, and the Katz ADL score for functional status. Pelvic organ prolapse was present in 65.3% women, urinary incontinence in 20.7%, overactive bladder in 9.3%, and anal incontinence in 0.7%. Sixteen percent of women were considered frail and 42% were “prefrail.” Dementia was determined in 21.3% of women, and functional disability in 30.7%. Pelvic floor dysfunction in women with frailty caused a significantly greater life-impact than in normal and pre-frail women. Forty-six percent of the subjects opted for surgery, but only women with functional disability, not impaired cognition nor frailty, were less likely to choose non-surgical intervention. The authors concluded that being able to identify women with PFD with risk factors of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability may help predict the risk of complications before surgery and help encourage behavioral changes and provide the appropriate pre and post-operative care for each woman.

A study by Erekson et al., (2015) looked into the prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability among women over 65 years of age looking for the best treatment for their pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD). A major concern was the presence of frailty being equated with poorer surgical outcomes. The 150 women in the study were tested with the Fried Frailty Index to measure frailty, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Score for cognitive screening, and the Katz ADL score for functional status. Pelvic organ prolapse was present in 65.3% women, urinary incontinence in 20.7%, overactive bladder in 9.3%, and anal incontinence in 0.7%. Sixteen percent of women were considered frail and 42% were “prefrail.” Dementia was determined in 21.3% of women, and functional disability in 30.7%. Pelvic floor dysfunction in women with frailty caused a significantly greater life-impact than in normal and pre-frail women. Forty-six percent of the subjects opted for surgery, but only women with functional disability, not impaired cognition nor frailty, were less likely to choose non-surgical intervention. The authors concluded that being able to identify women with PFD with risk factors of frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability may help predict the risk of complications before surgery and help encourage behavioral changes and provide the appropriate pre and post-operative care for each woman.

Silay et al., (2016) published a review on urinary incontinence (UI) in elderly women, relating its association with other geriatric conditions. Sixty-four females aged 65 and older were evaluated using the Turkish version of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) to assess UI and quality of life. Activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were used to evaluate functional status, and the Mini Mental State Examination was used for cognitive assessment. The comorbidities, pharmaceuticals, falls, and body mass index (BMI) of patients were also recorded. Results showed the subjects’ rate of urinary incontinence was 40.6%, and 28.1% of the women had their quality of life impacted. There was a statistically significant association using logistic regression between UI and quality of life, functional status, and comorbidity. Sadly, 50% of patients thought UI was normal with aging, 34.6% had been embarrassed to tell anyone about it, and 15.3% said they did not know UI was something for which medical treatment could be given.

Understanding how to manage frailty, cognitive issues, and functional deficits of our elderly patients can positively impact treatment outcomes. We should always strive to educate our patients and be aware of conditions that may be affecting or even contributing to their PFD. The Geriatric Pelvic Floor Rehab course can enlighten therapists on a score of comorbidities and techniques for handling those patients who are not sporting a marathon finisher medal to their physical therapy visits!

Erekson, E. A., Fried, T. R., Martin, D. K., Rutherford, T. J., Strohbehn, K., & Bynum, J. P. W. (2015). Frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability in older women with female pelvic floor dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal, 26(6), 823–830. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2596-2

K. Silay, S. Akinci, A. Ulas, A. Yalcin, Y.S. Silay, M.B. Akinci, I. Dilek, B. Yalcin. (2016). Occult urinary incontinence in elderly women and its association with geriatric condition. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 20(3): 447-451.

When my 6 year old daughter ran to the bathroom 3-4 times before she got on the school bus every morning, I wasn’t too concerned, but I definitely took note. The day she was in tears and wouldn’t get off the toilet because she felt like she was still wet, I got worried (although slightly intrigued). No matter how much she wiped, she still felt wet. When she stood up, she felt like she was going to pee herself, making my sweet-natured girl slip into hysterics. After eliminating small amounts of urine 8 separate times in 3 hours and saying it burned, I assumed she had a urinary tract infection (UTI). A simple urine test ruled out UTI or diabetes (thankfully!). So then, what was my daughter’s diagnosis? The pediatrician simply referred to it as “a phase;” however, I had researched the symptoms before the visit.

In 2014 Arlen et al. described a condition called “phantom urinary incontinence.” This refers to the situation when children experience the sensation of being wet (a presumptive urinary incontinence) when they are objectively dry. They considered 20 children (18 females, 2 males) referred to their pediatric urology clinic over a 5 year span, all who were all diagnosed with phantom urinary incontinence (PUI). The authors evaluated the concomitant diagnoses found among the boys and girls in the study. Lower urinary tract symptoms were present in 95% of the subjects. Associated bladder symptoms were found as well, with urgency in 75% and frequency in 50% of the children. Vaginitis occurred in 72% of the girls. Parents reported obsessive-compulsive disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder personality traits in 70% of the children. In order to treat these patients, dietary modifications, timed voiding, and a bowel regimen were implemented to manage symptoms. A follow up at 14.4 months revealed 90% of the children’s bowel-bladder dysfunction improved and PUI resolved. The authors concluded children compliant with a rigid bladder-bowel regimen experience relief of their “phantom” incontinence as well as lower urinary tract symptoms, and a majority of PUI patients have obsessive-compulsive traits.

In 2014 Arlen et al. described a condition called “phantom urinary incontinence.” This refers to the situation when children experience the sensation of being wet (a presumptive urinary incontinence) when they are objectively dry. They considered 20 children (18 females, 2 males) referred to their pediatric urology clinic over a 5 year span, all who were all diagnosed with phantom urinary incontinence (PUI). The authors evaluated the concomitant diagnoses found among the boys and girls in the study. Lower urinary tract symptoms were present in 95% of the subjects. Associated bladder symptoms were found as well, with urgency in 75% and frequency in 50% of the children. Vaginitis occurred in 72% of the girls. Parents reported obsessive-compulsive disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder personality traits in 70% of the children. In order to treat these patients, dietary modifications, timed voiding, and a bowel regimen were implemented to manage symptoms. A follow up at 14.4 months revealed 90% of the children’s bowel-bladder dysfunction improved and PUI resolved. The authors concluded children compliant with a rigid bladder-bowel regimen experience relief of their “phantom” incontinence as well as lower urinary tract symptoms, and a majority of PUI patients have obsessive-compulsive traits.

Oliver et al., (2013) studied how psychosocial comorbidities and body mass index relate to children with lower urinary tract dysfunction. Data on 358 patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction between 6 to 17 years old was collected, and the subjects’ parents completed questionnaires screening for lower urinary tract symptoms, stressful life events, and psychological comorbidities. Obesity was present in 28.5% of the children, 22.9% had a recent stress in life, and 22.9% had a psychiatric disorder. Under and overweight children, children with a recent life stressor, psychiatric disorder, or both, as well as the younger-aged children all had lower urinary tract symptom scores significantly higher than healthy weight subjects, those without psychosocial comorbidities, and older subjects. The results encourage screening for psychosocial issues and obesity in pediatric patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction.

Having read the research, I knew a life stressor was likely contributing to my daughter’s symptoms. I had already advised her to sit on the toilet every 1-2 hours, don’t let her bladder get too full, wipe gently from front to back, stop bubble baths, and wear looser pants. To conclude our $76 session, the doctor prescribed almost verbatim what my daughter had heard from me at home. Although thankful it wasn’t something more serious, I am curious what the diagnosis code is for “a phase” and when it will end.

Arlen, AM, Dewhurst, LL, Kirsch, SS, Dingle, AD, Scherz, HC, Kirsch, AJ. (2014). Phantom urinary incontinence in children with bladder-bowel dysfunction. Urology. 84(3):685-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2014.04.046 Oliver, J.L., Campigotto, M.J., Coplen, D.E. et al,. (2013). Psychosocial comorbidities and obesity are associated with lower urinary tract symptoms in children with voiding dysfunction. The Journal of Urology. 190:1511–1515. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.025

Perhaps you have seen the Facebook post by Alan Naughton (March 5, 2015) where a horse with one zebra leg tells another horse, “I can’t say I’m entirely pleased with my hip replacement.” Although this post makes some people laugh, I imagine surgical candidates cringe at the thought of complications. Few people hop onto a surgeon’s schedule with great enthusiasm. While hip replacements are sometimes inevitable for quality of life, other hip pathologies can be successfully treated with more conservative measures.

A case report in Manual Therapy (Lewis, Khuu, & Marinko 2015) described how postural correction and alternation of movement patterns were able to reduce hip pain secondary to acetabular dysplasia. A 31-year old female acute care nurse developed anterior hip pain with no trauma, and acetabular dysplasia as well as a labral tear were found. She got temporary relief of her constant ache and occasional sharp, intense pain from an intra-articular injection of cortisone. Her functional complaint was the pain prevented her from returning to recreational running. Intervention involved correcting the subject’s slight hip and knee hyperextension and posterior pelvic tilt with swayback posture, cueing her to walk on the treadmill with slight anterior pelvic tilt and contraction of the abdominals. This decreased her pain while walking from 6/10 to 2/10. Correction of the swayback posture decreased the hip flexion moment, decreasing stress on the anterior hip. At three months and then one year after the initial visit, she was relatively pain free. She still had pain with running, so she was advised to decrease her stride length and take shorter steps as well as decrease her hip extension by pushing off her feet more to minimize anterior hip joint reaction forces. With these cues, she was able to run without pain. Luckily for her, she had declined the option of acetabular reorientation surgery.

A case report in Manual Therapy (Lewis, Khuu, & Marinko 2015) described how postural correction and alternation of movement patterns were able to reduce hip pain secondary to acetabular dysplasia. A 31-year old female acute care nurse developed anterior hip pain with no trauma, and acetabular dysplasia as well as a labral tear were found. She got temporary relief of her constant ache and occasional sharp, intense pain from an intra-articular injection of cortisone. Her functional complaint was the pain prevented her from returning to recreational running. Intervention involved correcting the subject’s slight hip and knee hyperextension and posterior pelvic tilt with swayback posture, cueing her to walk on the treadmill with slight anterior pelvic tilt and contraction of the abdominals. This decreased her pain while walking from 6/10 to 2/10. Correction of the swayback posture decreased the hip flexion moment, decreasing stress on the anterior hip. At three months and then one year after the initial visit, she was relatively pain free. She still had pain with running, so she was advised to decrease her stride length and take shorter steps as well as decrease her hip extension by pushing off her feet more to minimize anterior hip joint reaction forces. With these cues, she was able to run without pain. Luckily for her, she had declined the option of acetabular reorientation surgery.

MacIntyre et al., (2015) presented a case study on conservative management of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) in a retired 22 year old elite ice hockey goaltender. A 4-year history of left anterior hip pain forced him into early retirement. He was diagnosed with longitudinal acetabular labral tears with a cam-type FAI. Before considering surgery, he had to undergo physical therapy, which he did 1-2 times per week for 6 weeks. Treatment consisted of Active Release Technique (ART)® and soft tissue therapy with tools directed to the affected gluteal , iliopsoas, and adductor muscles and fascial planes, spinal manipulation of the right sacroiliac joint, left hip capsule distraction/release using the Mulligan concept, contemporary medical electroacupuncture, and extensive rehabilitation exercises for lumbopelvic stability. After 8 visits, he had no pain at rest or with exercise. At 8 weeks he returned to playing ice hockey and now plays competitively again with no need for surgery.

I would venture to guess no one who takes the conservative route for treatment of hip dysfunction comes out of physical therapy with irreconcilable side effects. Being able to skip surgery using manual therapy and postural correction is a huge goal. If you doubt you can treat the hip effectively, taking Manual Therapy for the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex can not only enhance your manual therapy approach to treatment but also introduce you to an exciting visual feedback system to maximize efficacy of core stabilization exercises.

Lewis, C. L., Khuu, A., & Marinko, L. (2015). Postural correction reduces hip pain in adult with acetabular dysplasia: a case report. Manual Therapy, 20(3), 508–512. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2015.01.014 MacIntyre, K., Gomes, B., MacKenzie, S., & D’Angelo, K. (2015). Conservative management of an elite ice hockey goaltender with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI): a case report. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 59(4), 398–409.